PHOTOGRAPH

Antoinette

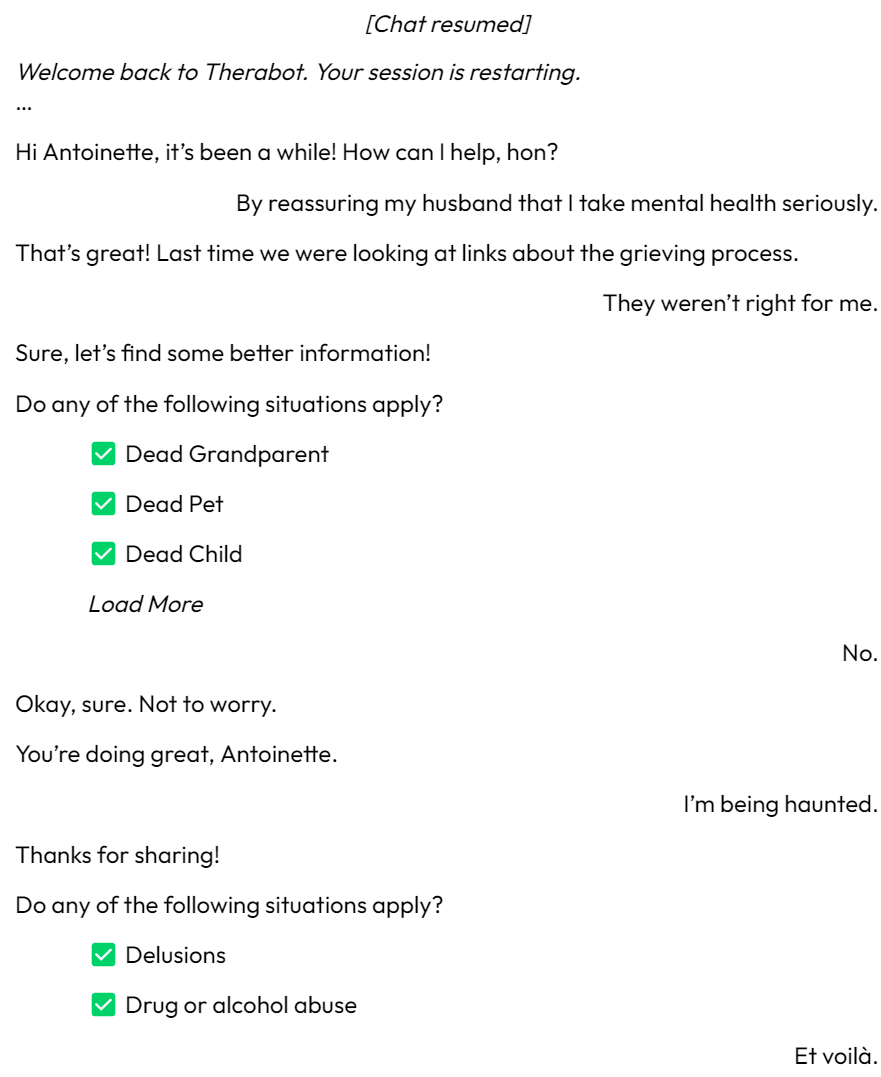

The postcard was scarred with raised white fold marks. Ana, sitting on her side of their beautifully-made bed, brushed her fingertips over the image. She was thrilled to have discovered it again. It was a photo taken on Bijushima, a panorama of the sea, the wharf, and an incoming passenger ferry. In the background, a shaft of light broke through the clouds and fell on the water. It was a god-filled sky. A perfect day. The photo had taken from in front of the Musée de la Mer; the edge of the car park barricade could just be made out in one corner. The place where, ten years ago, Antoinette had first met The Gargoyle.

The last rays of winter sun trembled on the horizon, picking out blades of grass. Antoinette’s shoes crunched against the loose gravel. The Gargoyle twitched; slightly-crooked shoulders lifted and dropped, but otherwise Antoinette was not acknowledged. So she stepped closer. They were alone.

Antoinette had endured John’s proposals as to the island's story:

'They needed a retirement village for all the worst grandparents,' or 'Anyone young enough to walk got up and left,' or 'Sun's harsh here. One year without sunscreen and you'll look like an octogenarian too.’

Making up stupid stories was easy; talking to strangers was hard. She came within a few metres of the Gargoyle, close enough that it would be beyond creepy to just stand there. She either had to speak or to leave.

"Everyone here is old," she declared to the figure's back. It seemed as good an opening line as any. "Where are all the kids?"

The Gargoyle turned and shot her a murderous look.

Antoinette took in her would-be killer. It was a girl. They were probably the same age. She was wearing a coat that looked to be stolen, based both on its style (men’s size large) and the contents of the breast pocket (a ratty pack of cigarettes.) The girl’s hair was cut short, and her mouth had a sulky set to it. The sleeves of the ugly coat were rolled double to show thin, dark wrists. A cigarette was smouldering between her index and middle finger. For someone dressed so rudely, she was strangely elegant.

Antoinette waited, her chin tilted imperiously. After a moment longer, The Gargoyle’s look of hostility cooled to suspicion. "It's not a good place for children," she said in a scratchy voice.

“Really? How strange.” Antoinette watched her own breath turn white in the air. “It’s so peaceful here.” She rubbed her hands together. “Sorry. I should let you know my—”

“You’re the architect’s daughter. They put your name on the plaque out front at the opening ceremony. I know who you are. So does everyone else.” She brought the cigarette to her lips. “Why do you think they've all been avoiding the gallery?”

The air suddenly felt colder, seeming to creep under the collar of Antoinette’s shirt and the cuffs of her socks. She shuddered at this suggestion of collective knowledge; the privacy of her little bubble with John was imaginary after all. They all knew where she was. Who she was. What she was.

“That’s...because of me?” Antoinette asked.

The Gargoyle didn’t answer.

By age seventeen, she had already encountered more than her fair share of sycophancy. Compliments from peers and adults had become predictable to the point of tedium. In her experience, adulation was rarely genuine and never deserved. She was so determined, so clever (like her father), so ambitious, so pretty (like her mother), so admirable, so brave (in the face of tragedy.) This girl’s naked contempt for her was bracing. Impressive. More than that, it seemed honest: an expression of the disdain Antoinette privately knew she deserved. Yet she felt compelled to redeem herself. She needed this girl to like her.

So she stayed. She sat down beside the stolen coat and the former stranger—her newfound nemesis—tucked within.

“Benefactor more than architect,” Antoinette said. “My father, I mean. He understands money. Not a lot else.

“This isn’t really fair, though. You know my name, and I don’t know yours.”

The girl looked as though she was weighing up whether to lie. “Kyou,” she said.

“Last name?”

The girl rolled her eyes extravagantly, but answered. “Kyou Nakajima.”

“Kyou Nakajima.” Antoinette repeated. “It suits you.”

“It’s just a name.” Kyou tapped ash onto the earth. “Either I'll grow into it or it’ll have to grow into me.”

“Huh,” said Antoinette. “I suppose I will be a ‘Williams’ one day. That’s my boyfriend’s last name.” She studied Kyou’s face for a sign that this admission had made an impression. Scandalisation, piqued interest—Anything. She had never referred to John as a boyfriend, let alone a marriage prospect. The idea was still outrageous to her! It deserved a reaction.

“Cool,” said Kyou, as though Antoinette had just told her the time.

“Cool,” Antoinette echoed, defeated.

In the dying sun, the harbour on the mainland changed colours, salmon bruising into indigo. Port and starboard lights flickered. Tugs and forklifts would keep on beetling along through the night. Trucks would load or unload their cargo and head off beyond the mountain range. Meanwhile, the little settlement of Bijushima was gently turning towards slumber.

“I can show you, if you're sure,” Kyou said, dropping the cigarette and stamping out its glow. “If you really want to know what happened to the children.”

And that had started it all. In the safety of her apartment, years and miles away from the memory, Ana turned her mind to the present and flipped the postcard to read its message:

5 May 2007

There was once an attendant to a capricious Goddess. The Goddess blessed the world with all its light and warmth, and all its fire and war. The attendant, who was lovely and might have married under better circumstances, was made to wrangle the sun into place by threads of sunlight and fan flames ever higher using only her breath. It was rotten work.

Every night she would ascend to the highest clouds to tuck the Goddess in to rest, and every night she would look longingly at the vertiginous drop to Earth. Her hands were burnt and her joy was spent.

Then one day, after hours of raising the sun and encouraging an inferno that swallowed a village whole, the attendant made up her mind. After soothing her mistress to sleep, she tiptoed to the precipice of the divine bedchamber, turned, leant back, and fell.

The wind whistled sweetly in her ears as she hurtled towards death. Passing stars bade her farewell. Abstract shapes became mountains, forests, rivers. She hit the earth with the force of a comet.

To her great distress, she lived.

Ana tucked the postcard back with the others. They were all stashed between the pages of a book she’d chosen because John would overlook it. It was old and thick and entitled Light as Memory.

The afternoon sun sharpened and then faded through a prismatic haze of soft rain. Her appointment was approaching. At close to eight, Ana made her way back to the exhibition space. It felt distinctly alien in the dark, now empty of visitors. She tied back the curtain at the mouth of the tunnel and set up a tripod and flash kit to focus on a waiting barstool. The interior mirrors would be difficult to manage. Bringing a technician would have been sensible, but she wanted no intrusion.

Kyou arrived late without apology, formally dressed. She stalked around the lighting cables like a cat surveying changed environs. She inspected the shoot-through umbrella and cache of lenses. Ana watched her. Did this figure display signs of the girl from Bijushima? Yes. It was foolish to have missed it. The new hair and eye colours were a distraction, but otherwise she was there. All there. She still had the same thin frame and rightwards tilt to her shoulders, the same pout and enquiring gaze.

Too much had happened in the intervening years. It all flooded Ana’s mind and numbed her tongue. There was everything to say. There was nothing to say. She directed Kyou to her seat and began working through a series of lighting tests. Ana adjusted the shutter speed to pick up the background glow. She dropped and tilted the camera. She tweaked the focal length. There.

Through the camera’s viewfinder, Kyou looked like a petulant schoolboy, an echo of her teenage self. It was bewildering. In the tunnel, time was blurring like a long exposure.

“You stopped writing to me,” Ana said into the silence.

Her sitter looked up with an expression of sudden remorse. The camera clicked. The expression passed.

“Ran out of postcards,” the accused supplied. Her light hair and the white of her shirt were luminous under the blue fluorescents.

“I sent you full envelopes,” said Ana. “You sent me riddles.”

“Ha! No loss then.” Kyou gave a roguish grin. The camera clicked thrice.

“I didn’t think I’d see you again. I’m surprised to see you now.”

Kyou shrugged. “I was only a little late. Half an hour or—”

“Ten years,” said Ana, “by my count. You weren’t there when I went back to Bijushima. I thought you'd be there.”

Kyou inclined her head, looking up as though the false ceiling might offer an answer. The angle made hollows of her eyes, shadows below her fine cheekbones. Perfect. It was an image of pre-Raphaelite drama; the face of one freshly fallen from grace.

The camera clicked busily.

“I moved,” Kyou said, then looked down the barrel of the camera, “but I heard about your visit. And what happened.”

Ana paused. She wasn’t at all prepared. She took a breath, pushed a lock of hair behind her ear and forced a smile. “That’s strange. It’s not like my father to miss a non-disclosure agreement.”

“My aunt knows the girl who worked in housekeeping.” Kyou said. The camera clicked.

“That’s unfortunate,” said Ana. “I hope The Girl was suitably compensated.”

“She was suitably messed up.” Kyou raised an eyebrow. “Found your blood all over the hotel sheets and the door to the ensuite locked.”

Ana remained silent.

“Is that what happened to your wrist?” Kyou asked. “The scar I saw when I stamped you for entry? When you came to the club?”

Ana wasn’t inclined to offer an explanation. The entire episode sounded so juvenile when Kyou recounted it. After a moment that seemed to stretch for months, Kyou closed her eyes.

“The girl resigned, moved to the mainland, went to a technical college, and got a job in marine biology.”

“Beautiful. A fairy-tale ending.” Ana responded in a higher-than-usual tone and took several more photos.

Kyou looked to the side, an impression of a reluctant graduate getting their portrait taken. It made for an awful picture.

“So you moved?” Ana asked. “Your mother finally left the island?”

“No.”

“She didn’t? Then who did you move with?”

“People from work.”

“What kind of work?”

“Work-work.” Kyou said, apathetically. “The Club.”

“Don’t tell me you started there as a child.”

Kyou didn’t tell her anything. She looked down at her fingernails. She rolled her shoulders.

“So you were in Tokyo the whole time?”

“Yes.”

“But you didn’t think to see me?”

“No.”

Ana sighed and took a moment to scroll through the last set of stills. It wasn’t working. Not the suit. Not the scowl. Not the defensive attitude.

“I need to make adjustments.” She strode towards her increasingly circumspect model. “Do you mind?”

The tie Kyou was wearing wasn't helping. Too formal. Ana tugged and loosened it.

“I’m taking this off.”

“Why?”

“You don’t look like yourself,” Ana said. “You look like a stranger.”

“I am a stranger. I don't even exist.”

“Stop it.”

Ana wrapped the silk around her knuckles several times, stepping to the left and right, crouching, bobbing, assessing the reframe. She placed the tie on top of her handbag and advanced on Kyou again.

“And just these first two—three—buttons, I’m undoing these, okay?” She grasped the shirt collar without waiting for confirmation.

“Why did you hurt yourself?” Kyou took Ana’s wrist.

“Why weren’t you there?” Ana pulled open a button. “Why did you stop writing?” Another. “Why didn’t you find me?” Several buttons followed. Then she stopped. She exhaled, recalling herself. She stepped back.

“Better?” spat Kyou defiantly.

“You have bandages.” Ana said. “Why—?”

Kyou looked down, confusion giving way to amusement. She gave a low chuckle. “That’s binding.” She shook her head. “It’s just for work. Nothing serious. Heading straight there from here.”

“I’m sorry.” Ana said. “I don’t want you to be uncomfortable.”

Kyou huffed, perhaps a little uncomfortably. “I’m fine.”

“The white picks up well in the light."

“So shoot me.”

Ana returned to the camera. The space was cast in the full spectrum of blues: deep midnight shadows, gas-flame brightness. Kyou’s vision settled in the middle distance, lost in thoughts she did not share. The session was completed without further comment or incident. Kyou was already late for work, and she apologised for not staying to assist with the pack-down. Her politeness was awful.

As she went to leave, Ana asked something she would regret. She sounded like a ridiculous child.

“Do you hate me?”

Kyou cocked her head, expression unreadable. Then she moved towards Ana and patted her shoulder. She did it like a kindly police officer with bad news. Like a useless relative at the end of a funeral. Like a father who had speeches for everyone else but never for her. Like a stranger.

“I kept all of your letters,” Kyou said. “I know you far too well to hate you.” And she left.

Ana deconstructed the lighting rig, wound down the telescopic poles, and laid each piece the delicate camera gear to rest, snug in its assigned pocket. It was only when she had snapped the cases closed and turned to collect her handbag that she noticed the silk tie still coiled and waiting.

Ten years ago, when she had been young and foolish, it had seemed entirely reasonable to dart off into the night on a strange island in search of secrets. There was no other option. If the idea of The Gargoyle had been compelling, the girl called Kyou was more so. When Antoinette reappeared in her thick coat, she felt self-conscious about its cost. Kyou didn't notice.

Antoinette followed her guide down the road from the Musée and through the lampless streets, between the houses of people who were supposedly avoiding her. Intermittently came the sounds of microwaves, chopsticks on crockery, television game shows. Yellow light spilled from windows along with the scents of broth and scallions, grilled fish on hot rice, sweet sesame and ginger. Nothing like hotel food; the hotel restaurant specialised in a dull approximation of European cuisine.

“Wait here,” Kyou hissed when they came to a property with a flag proclaiming ‘Welcome.’

Antoinette did as instructed, praying feverishly that this wasn’t some prank and that she wasn’t being left to wait and die of pneumonia in the wintery night. If she survived, John would never let her live it down. You followed a weird villager who didn’t like you? At nighttime? On a remote island? Have you never watched a horror movie?

The growl of a car engine made her jump There was nowhere to hide. If one of these neighbours found her in their headlights, then what? But it wasn’t a neighbour; it was Kyou, quite illegally driving old Toyota station wagon.

“My Aunt’s out cold in front of the TV,” she explained. “Get in.”

“Are you even allowed to—”

“Please. It’s fifteen minutes to lap the island. I could do it with my eyes closed. Takes a while walking. You’ll freeze before we get there.”

It was a compelling argument. Antoinette got in, luxuriating in the warmth emanating from the heating vents. The drive took them away from the houses, past a cluster of closed stores, and up into unfamiliar hills. The car juddered. She suspected they were no longer on a formed road, but Kyou’s confidence never wavered. They continued through a cedar forest, the high beams revealing a glitter of dust and insects. In time, the tree limbs gave way to a clearing where a modest temple stood.

“C’mon,” Kyou said, stepping out and shutting the door, leaving the high beams on. Antoinette hurried to follow. Without the headlights, it would have been impossible to see more than a metre ahead.

They proceeded through the wooden entrance gate and along a pathway, pausing to wash their hands and mouths in the frigid water from a stone basin. The main hall was closed; Buddha had shut up shop for the night. In the headlights, their paired shadows stretched before them, and they were flanked by stone lanterns with eyes of orange light that emitted a dim electric buzz. Kyou turned to the right and gestured to a gathering of evenly-spaced Jizo statues, little stone people with perfect little smiles, each no taller than a foot. Many of them were dressed in red bibs. Very cute. There might have been two hundred or more.

“Nothing is for free,” Kyou said, “and that includes your gallery.”

Antoinette waited in silence, hoping that the sinking feeling in her stomach would pass.

“What happens on Bijushima isn't decided on Bijushima," Kyou went on, her face in shadow. "We come under the local council—people on the mainland. They worked very hard at convincing your father’s company to convert a fishing village into a tourist attraction.”

“I don’t understand,” said Antoinette, growing colder in the stillness.

“‘Kanto Electric keeps the nation switched on.’ Remember that ad? It also keeps everyone in work. So sometime in the 80s, one of its businesses—like a subsidiary of a subsidiary or whatever—set up a factory. It’s on an island five or so minutes from here. It all started out okay; there were jobs and money. People started moving in instead of away. Then things got rocky when 90s bust happened. The money ran out. People cut corners.” Kyou crouched down and straightened a wayward bib on one of the statues.

“Strange things started happening on Bijushima. There was this cat that used to live in the ferry building, met with the fishermen every morning. It was like the village mascot. Anyhow, one day it started doing this crazy dance, like it was possessed. Then it threw itself off the jetty. Couldn’t swim. Everyone loved that cat, apparently. They were shocked. It seemed like a bad omen. Then something similar happened to Mr. Yamada's dog. Then a bunch of other pets. Seabirds. They just lost it. Went mad. Snuffed it.

“Then, y’know, it got worse.”

Antoinette’s knees were starting to quiver. She looked up at the inky sky. Snow was falling; it caught in her eyelashes.

“How?” she whispered.

“There was a series of unexplained drownings from the fishing boats. Then women started miscarrying. Those who didn’t...I dunno. I guess they wished they had. After that, anyone with a kid in school, or who hoped to have one, moved away from the island. Well, almost everyone.”

Kyou gave a bitter laugh. “My mother didn’t. Never leaves. Won’t go near the ferry." She looked directly at Antoinette, who finally spoke.

“Mercury?”

“Mercury.” Kyou confirmed.

Antoinette forgot how to breathe. The snowflakes burnt her skin.

“Run-off from the factory had been poisoning the fish. Then the animals ate the fish. People ate the fish.”

Antoinette half fell to kneel before a red-bibbed statue. The ground was rough and freezing where it met her bare knees.

“I don’t know how they figured it out. It took them a few years,” Kyou continued. “But news got back to the Kanto guys with enough money to worry about liability. If anyone from Bijushima wanted that money—felt they might be owed that money—Kanto would pay out. They just had to sign a confidentiality agreement.

“Their secrets were meant to die with them, but that’s not how it worked out. It got expensive. People kept coming forward.”

“How many?”

“Hard to say. Confidential. Anyhow, that was the condition, the agreement with the council: a line in the sand. Construction of the galleries on Bijushima would go ahead if the council indemnified your father's company for any future payouts for the mercury leak victims. That was the condition. Just one little condition in exchange for the benefit of tourists flooding back to the region.

“The council said yes. Fucking mainlanders. Obviously, the council didn’t have any money—just a lot of forms and red tape. People eventually gave up on asking. It was guys who couldn’t concentrate enough to do a day’s work or had kids with growths the size of baseballs. Regular old people whose whole families had fled.”

"All of those…" Antoinette's heart was thumping at a nauseating pace. Her pulse was in her ears. In her throat. She wanted to deny it all. But then...but then Kanto. Her father. And his endless secrets…

"I had no idea,” she stammered. “I just—"

"Thought you might want an idea,” said Kyou. “What an island costs. A whole island. For one sad little girl.”

It was hideous. Antoinette swallowed down the urge to be sick right there. Not in Buddha's front yard. She folded her arms over her chest and tucked her head down like a bird. Her breath came in little puffs. She thought of baseball bulges, feeling them in her stomach, her neck. She thought of the dizziness, of the loneliness, of the confusion of forms. She thought of all the jokes about old people. She swallowed down the sick taste in her mouth. The ground was covered in bleak white.

“You hate me,” she stated.

Kyou didn’t answer. Nor did she walk off and leave. The sea of miserable little stone faces was disappearing under quiet snow. Infant faces. Antoinette’s head pounded. There was something inevitable about this story. It seemed natural that she should be at the root of horror. Her own mother had found her horrific, had chosen to escape a life of being tied to a strange child that looked like her but behaved like a foreigner. Now Antoinette was responsible for this: the desolation of a community. She was the poison.

“I don’t hate you,” Kyou murmured, kneeling as well. “I just wanted you to know.” She fidgeted. “I think I wanted you to fight me. Or call me a liar. Just give me a reason to—I don’t know...I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be,” Antoinette smoothed a bib, patted a stone head. “So this temple is where the village comes to remember its lost children. You should hate me. I come from a hateful man and a—” She choked. She swallowed. “Maybe I was too much like him. Maybe that’s why she—”

“Maybe you’re just like yourself," Kyou interjected. "Maybe you’ll marry your boyfriend. Become a Williams or whatever. Just like you said. Make happy children—”

“Gross.”

“I’m trying to help you out here,” said Kyou.

“Why?”

“I don’t know. I should've left you alone.”

Antoinette sighed. “No. I would rather know. It’s better that I know.”

“I’m sorry,” Kyou repeated.

“What can we do for them?” Antoinette looked over the stone figures. “I need you to help me. I don't know what to do."

“Well, sure. I guess we remember them for Obon. The families and their kids come back to visit. There’s a big bonfire, a tower out in front of your gallery. I do the drumming, ‘cos, y’know, everyone is old. Afterwards, we go down to the beach. We light lanterns and send them off into the water. You could light one too. For your mother.”

The headlights went out. Kyou cursed and muttered something about the battery. The snowfall was getting heavier. It was black as hell away from the glow of the lanterns. Trekking into the forest would be suicidal. They would have to shelter in the car. They would have to shut in any residual warmth from the heater. They would have to hold onto each other. They would have to pray for morning.