GARDEN

Miu

There were two things that occupied Miu’s time. The first was copying, addressing, and dropping off a story from her journal every week. She wrote ‘Megumi’ on the envelopes that she left at reception at the old age home. She knew she couldn’t afford the sessions, but this ritual still felt like progress.

Miu’s second occupation was gardening. In the early spring, the camellias dropped like broken hearts. Miu braved the morning chill to kneel on stone and scrape away lichen. Log fires tended by slowly-waking neighbours scented the air. Smoke drifted and curled above the black pine to mimic the arcs of its sculpted tufts. The cat she was ignoring appeared atop her fence and scampered over to butt its head against her arm. No use in a cat.

“Tsu,” she admonished.

It purred in response.

She stuck out a finger to stroke its silky neck, then cast a pebble into the grass to distract it. The cat leapt away.

Restaurant owners grumbled and the gallery workers became listless, but for Miu Nakajima the off-season was the kindest time of year, a return to long-lost calm. The inn was her home. Hers. It was silent, and the smells of foreign shampoo, spilt beer, damp luggage, and awful diets had been bleached, scrubbed, and polished away. The screen doors had all been opened for the house to take in the breeze.

Today she needed to sharpen her tools, plant the iris bulbs, prune the apple tree, and mend and replenish the bird feeder. (Really, a cat was no good to have around.) With all these tasks awaiting her, she was less than enthused to hear the tell-tale rattle of her sister’s trundler approaching her gate.

Of course.

It was the Ladies En Plein Air gathering. She was coming to borrow watercolours and “whatever that stuff is you use with them.” Her sister was neither a painter nor a fan of nature; she was in it for the gossip.

“Good morning, lo-ove…” she sang out.

Reluctantly, Miu stood and brushed the dirt from her skirt.

“Woo—cold in here!” her sister continued. “You want to use that heat pump? Where’s the remote?

Miu moved quickly into the lounge. Upon catching her sister’s attention, she raised a palm in a ‘wait’ gesture and left for her study to gather the set of art supplies she had set aside for just this interruption. Her sister hummed away.

“The ladies are putting on a show. Very exciting. The theme is…what was it? ‘Murasaki: women’s voices.’ Something like that. It’s femi-nin-ism. You know, the Genji story? They arranged for a man from a university to come and talk about it at the opening. The big gallery is letting us use the foyer space, and they’re doing the catering. Fancy, huh? Plein air is perfect for painting romantic scenes for fairytale princesses. I said you would put in something. With your calligraphy. The ladies were very happy.”

Miu, who had returned with a canvas bag, easel, and pad of expensive paper, blanched.

“Tsu, tsu.” She looked at her clean floorboards.

“Ah. I knew you’d be like that. Stop it. I’m not making you come to the group. I’m just saying share your work. You’ve already got those pieces in the local section of the gallery shop. What’s the point of your hundred perfectly painted poems that no-one can read?”

“Tsu,” Miu repeated, and held out her supplies.

“Ah! Look out, I'll be a Picasso yet!”

“Nn.” Miu couldn’t restrain the quirk of her lip.

“Not Picasso?”

“Tsu.”

“Some other one then. Duh-lee? No? Ah! Moh-ney! Yes? Yes. Okay, that one.”

“Nn.”

“This is the best.” Her sister began packing the paints and brushes into her trundler. “I can’t wait to hear about that Sumire kid. Sounds like he’s become one of those shut-ins. So weird! Anyhow, maybe get in touch with that daughter of yours, give her a picture of your garden or something. She’s been asking about her father again. Sending messages late. Same thing again and again. Terrible spelling. Maybe it's a breakup or something? She never tells me.”

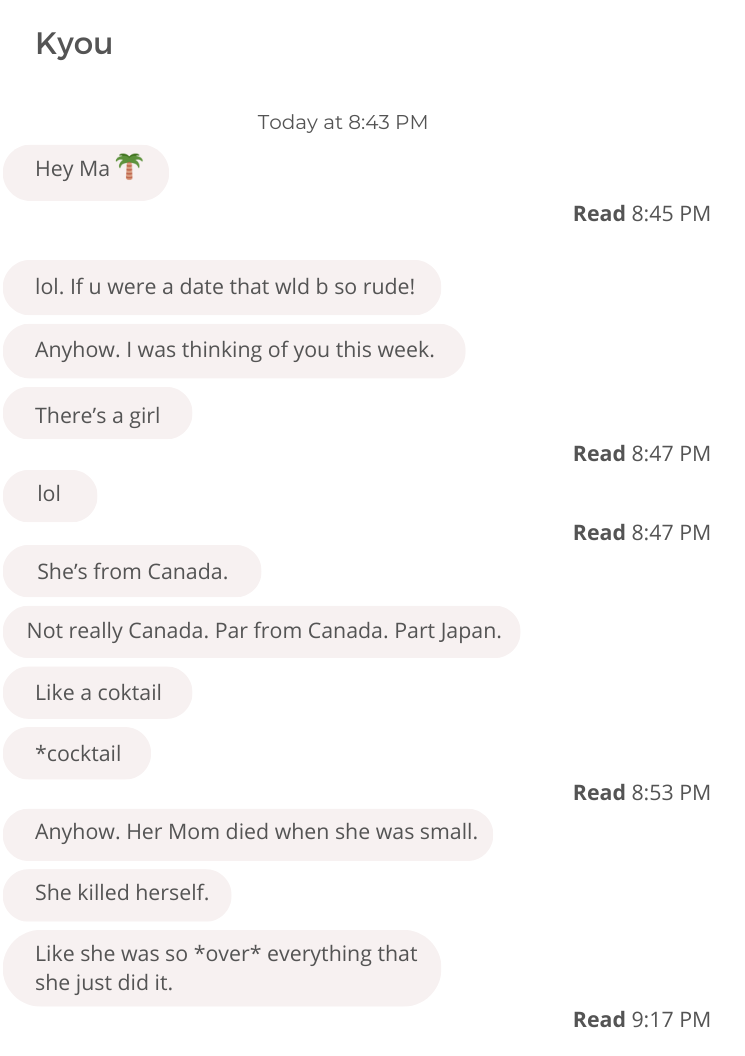

Once her sister had clattered off on her way, Miu found the cat had neatly curled up and dozing amongst the fallen red flowers. She took a picture of that and sent it to the ‘chat’ with her daughter. She scrolled up. Her sister was right.

Miu kept the phone for the benefit of her sister and daughter. They had long accepted they would not receive text responses, but they could see when messages are marked as Read. Miu’s daughter only sent messages periodically, and often at a time of night when her state of mind was suspect.

Miu placed the phone face down on the stone and picked up her tool. Poor girl. So it was the daughter of the gallery owner, presumably. The one Kyou felt she had to re-introduce every time. Poor girl. Of course she wouldn’t just leave. She had toyed with the idea, certainly, but that was only when she wasn’t sleeping enough.

Back then, when things had been bad, memories screamed and clawed and threatened to break her skin, bleeding into her dreams until there seemed to be no peace, awake or asleep. There had been so many doctors, almost-doctors, doctor’s assistants speaking in sing-song voices reserved for children. Tsu! She was no child. She was a grown woman who had made a painful decision. Speak no evil. At the beginning of her silence, she believed she could feel the badness swimming up inside of her, desperate to escape, like an awful spirit. It made her dizzy, nauseated. Then she actually did start getting sick. It was awfully undignified. The spirit would wrap around her stomach and pulse until it felt like a second heart. Sometimes just the smell of her sister’s tea would awaken the spirit. Its yellow eye would crack open, flicker, and bulge, and it would wind around and gnaw at her organs until she had to stagger to the bathroom. Sometimes, to her dismay, she only made it to the kitchen sink.

The doctors and not-quite-doctors looked at her with a strained kind of friendliness when they explained it was just morning sickness. She was pregnant. They watched her with hot eyes as she placed her hand on her tormented stomach.

They nodded.

She nodded back.

“So, if you…?”

“Nn,” she intoned.

“Yes? Yes, Miss Nakajima? Were you going to say…?”

No. No, she wasn’t trying to say. Oh. They were painfully excited about tricking her into speaking. She was exhausted. It was becoming irksome. She stood up, hand still on her stomach, and moved to the kitchen to get some hot water.

“Nn,” she said again, more quietly, to her stomach, in which there was no cruel spirit at all, was there? Would it be a good baby, she had wondered? Foolishness. A mischievous baby, to be sure. But never cruel.

Around the time Kyou (as yet unnamed) was starting to kick, Miu busied herself with visits to the little library to read through the books on maternity. There was a lot that she regretted reading. Some of it also bled into her nightmares. One of the books—evidently intended for children—had a painted picture of an infant, curled up like a kidney bean and floating in a vast starry sky. Just like an astronaut, it was connected by a safety line back, back, all the way back to its mother. Miu thought sometimes of that image, how frightening and expansive the void, how vital that safety line. She knew, even while Kyou had no name, no voice, no apparent objective but to kick blindly and lean on her bladder, that the safety line went both ways.

So, no. No to these silly late-night worries. No to little icons of broken hearts. She would show the messages to her sister and hope some reprimand was forthcoming—or perhaps she wouldn’t. It might stop Kyou from sending more messages. (It would.) Miu wished a father were there to take it up with her daughter. He would grab her by the shoulders and sit her down. He would use his rough voice to smooth of the edges of her doubt. He would explain that she always had been loved and always would be loved, far, far too much for anyone to disappear and cut her adrift to float further from the warmth of the sun, growing colder, smaller...Lonelier. She should never feel lonely.

That poor girl and her broken heart.