Despite its proven efficacy in the treatment of so-called intractable childhood epilepsy (seizure disorders that have failed to respond to the proper use of three or more anticonvulsant medications), the ketogenic diet is still regarded as the “treatment of last resort” by many neurologists and other physicians who manage seizure patients. As the diet gains more popularity around the world, studies have shown that some of the old myths about how the diet can be used are incorrect.

We now know that the ketogenic diet can be helpful in the treatment of both generalized and partial seizures, although it is less likely to be as completely effective in the localization-related (partial) epilepsies. It can be successfully implemented in a wide range of ages without any clear influence of age on outcome. There is value in using dietary therapy short term in children who may ultimately require surgical intervention, especially when they are young children. It may have value in such cases for status epilepticus, in fact.

The ketogenic diet can be used as “first-line” therapy in certain situations, and actually there is agreement that it is the “treatment of choice” in specific epilepsy syndromes. The two prominent examples of first-line treatment are the glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1) deficiency and pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency (PDCD) syndromes. GLUT-1 deficiency syndrome is a rare disorder in which the brain cannot get its necessary energy through glucose metabolites because they cannot cross the “blood-brain barrier.” By maximizing the body’s level of ketones in a controlled and healthy way through the use of the ketogenic diet, there is a new energy source made available to the brain so that it can function properly. Recent studies would suggest that the diet may not be a lifelong treatment for GLUT-1, and it could possibly be stopped in adolescence.

PDCD syndrome is a rare neurodegenerative disorder, usually starting in infancy, that is associated with abnormalities of the body’s citric acid cycle. Proper production of carbohydrates is interfered with, and there is a resultant deficit in energy throughout the body, accompanied by a dangerous buildup of lactic acid. The result is damage to the brainstem.

In these two illnesses, the ketogenic diet acts as both an anticonvulsant treatment, as well as possibly treating other, nonepileptic, manifestations of the underlying metabolic derangement. Early consideration and confirmation of these two diagnoses offers the possibility of avoiding all or at least some of the devastating lifetime developmental condition resulting from a disease, injury, or other trauma.

The evidence is certainly less clear when consideration of the ketogenic diet as primary therapy is expanded to other epilepsy types and syndromes known as age-dependent/age-specific epileptic brain disorders. Examples are Ohtahara syndrome (early infantile epileptic encephalopathy with burst suppression), which is frequently associated with central nervous system malformation; West syndrome with infantile spasms, hypsarrhythmia EEG pattern, developmental arrest and/or regression; Lennox-Gastaut syndrome with slow spike-wave on EEG and multiple seizure types; early-onset myoclonic epilepsy frequently associated with metabolic abnormalities; migrating partial epilepsy of infancy; and Dravet syndrome (severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy) with atypical early onset febrile seizures that become intractable mixed seizures and are associated with the SCNA-1 gene mutation in 40% of cases.

West syndrome is the most studied and there is lots of information that in about half of children who are started on the diet, about 90% of the spasms may go away. What is most interesting is that the sooner the diet is started the better the outcome. Knowing this, why not use it first? We have done that—data from our center show that there is no difference in the time it takes to seizure freedom comparing treatment with the “gold standard” adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) versus the ketogenic diet. While the EEG improved and normalized faster with ACTH at 1 month in spasm-free babies, there was no difference at 2–5 months. Most significantly, the incidence of side effects was lower in the babies treated with the ketogenic diet, as well as the risk of the spasms coming back. We now use the ketogenic diet routinely here at Johns Hopkins as a first-line therapy.

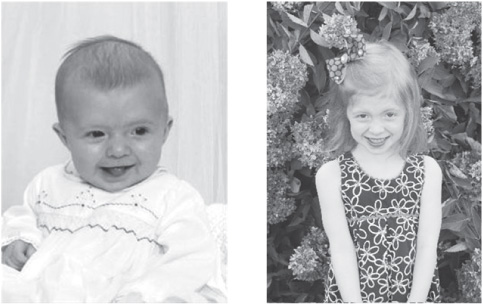

FIGURE 24.1 and 24.2

Carson Harris, one of our babies with new-onset infantile spasms treated with the diet alone, at 6 months when she developed spasms and today, now normal (see Chapter 13 for more information about The Carson Harris Foundation).

Courtesy of The Carson Harris Foundation.

These are severe, early-onset epilepsies that have gotten the attention of ketogenic diet centers, but early therapeutic intervention has been restricted by the belief that the ketogenic diet is unsafe for use in newborns and infants. Data published 15 years ago reported that the infant brain was four times more efficient than the adult brain in extracting and utilizing ketone bodies. In 2001, in a retrospective study summarizing the experience treating 32 infants under age 24 months, it was concluded that “the ketogenic diet should be considered safe and effective treatment for infants with intractable seizures.” Additional publications show that the side-effect profiles of ketogenic diet use in very young children do not differ significantly from older children, which should lead doctors to increased consideration of the diet in this population. All these “catastrophic” epilepsy syndromes of infancy merit controlled studies to determine which are most likely to respond to initial or early ketogenic diet treatment as opposed to anticonvulsant medications.

There is also recently published research that reviews the usefulness of the ketogenic diet in status epilepticus, an acute life-threatening state where the brain is in a persistent state of continuous seizures. Early use of the ketogenic diet administered via gastric-tube (g-tube) feeding may be a rational therapy in certain specific febrile-seizure status states in school-aged children (the FIRES syndrome). Seizures from tuberous sclerosis complex and Rett disorder are very difficult to manage with medication, and there appears to be a role for very early use of ketogenic diet therapy once those diagnoses are confirmed and seizures begin.

Doose syndrome is an epilepsy syndrome of early childhood that is often resistant to medication and where the ketogenic diet offers a combination of virtually immediate seizure relief and long-term control. The Doose syndrome clinical and EEG pattern is clearly recognizable, and although up to this point in time medications are being used initially, the ketogenic diet allows the rapid discontinuation of medications, with seizure freedom even when the diet is stopped after 2 years. Multiple studies have shown that the diet is the best treatment for this condition, and nearly all these articles comment at the end that it should be considered “sooner” than as a last resort. At our center, we will mention the diet as soon as the first visit and at times offer it before medications. However, if one drug fails, especially Depakote®, we will strongly push the diet as the next choice.

There are some barriers in the medical system to using the ketogenic diet first. First, dietitians and neurologists have to change their mindset about the diet and consider it an appropriate “emergency” treatment option. That means dropping everything to start the diet and not putting these children on a waiting list that might take months. Insurance companies may not agree as well, and families might have to accept a financial burden if that happens. Second, parents would have to give the diet a chance to work. Although data would suggest that for infantile spasms the diet works within a week or two, in our experience the family is often very impatient if there is no benefit within days. The family would also have to understand that if the diet did not work, then they’d have to stop and move on to medications (especially for West syndrome where time is of the essence). Lastly, the education process for starting the diet would have to be shortened and streamlined. If not, a 4-day admission for education would certainly seem much more difficult than a 1-minute signing of a prescription. This book may help, along with the Internet and other resources, but the diet will need to be made easier and quicker for sure.

What is clear is that in 2011, the ketogenic diet is not an appropriate “last resort.” Even if it is not being used first, it should be mentioned earlier in the treatment of epilepsy, certainly after two drugs have failed. By the time the 6th edition of this book is published eventually, we suspect the diet will be widely used as a first-line therapy for many of the epilepsy conditions mentioned in this chapter.