July 15, 2090, Bainbridge Island, Washington

Parker Timothy Olstead II

The dog follows them up the beach and down the trail to the cluster of low houses with sloped, mossy roofs. They stop at the second house from the street, Camden and Twila’s, and Spud tells the dog to wait, even though he knows it will anyway. His aunt says he’s “got a way with animals.” He spends hours observing the creatures that live along the beach and in the woods. He tries to read them like he would a book. He knows their habits, and usually he can get them to do what he wants. Frogs will rest on his knees if he puts them there. Once, a heron ate breadcrumbs from his hand, its long neck stretched out to reach him. The dog is loyal and shows no interest in anyone else.

Inside, Camden leads him to the basement—ostensibly toward paper-work she’s found relating in some way to his father. He only half way trusts such a thing really exists. Camden has always been a liar. Though it’s only the last year her lies have turned mean. Or, if not mean, manipulative. Lies to control, lies to confuse.

There’s part of him that wants this to be just another one of those lies. That way he won’t really be breaking the promise he made to himself on the beach just an hour ago—no more pathetic pining for his dead and absent parents.

He’s been in this basement before, but not for a long time. Not since he and Camden were small, back when they were real friends and used to play hide-and-seek while his aunt and Camden’s mom clipped coupons in the kitchen and did whatever else. In the basement, there’s a couch, a desk, three mismatched chairs and a file cabinet. Camden opens the bottom drawer of the cabinet and makes a big show of sifting through it. He wonders if she actually found the file somewhere else in the house and re-hid it here as a means to get him down to the basement, where, even if Twila does come home suddenly, they won’t be interrupted. That would be just like Camden—always thinking one step ahead of him, getting him to do exactly what she wants, when she wants, where she wants.

After what seems like too long a time, Camden pulls a worn-looking manila envelope from the drawer and holds it up. The envelope is, as Camden promised, fat with papers. The edges are creased and torn in some places, exposing white pages within.

“See?” she says. “I told you.”

“Lieutenant Colonel Olstead” is printed neatly across the top and a return address for the University of Michigan in the right corner. He grabs for the envelope and is surprised when Camden drops it into his hands without a struggle. Inside are pages with numbers: cholesterol, white blood cell count, height, weight, pulse. Spud feels his phone vibrate in his pocket. He ignores it. He knows it’s his aunt because she’s the only person who ever calls, and she only calls when she has some chore she wants him to do. He doesn’t want to do her stupid chore today. As a man of thirteen years old, he shouldn’t have to, he decides. He keeps flipping through pages, but none of them mean anything to him. A red stamp appears on the last sheet of paper. APPROVED.

“It’s just medical stuff,” he says.

“Does it look important?” Camden asks.

“Well, he’s dead, so it can’t be that important now.”

“I mean does it tell you anything about him as a person, idiot.”

“Tells me my dad once got a physical at the University of Michigan. So what?”

Camden reaches for him and he shifts to avoid her, but she only puts her hand across his. The touch surprises him—tenderness he’s not used to from his neighbor. He feels hot tears welling up behind his eyes. He doesn’t want to cry.

“I’m sorry, Spud,” Camden says. “I was really just trying to help. I don’t have a dad either and I know how much...” But he hardly hears her. He needs to get away from her. She’s lured him into breaking his promise to himself and for what? The tiniest scraps of information. As if information would bring a person back to life. Stupid.

Worse still, the information she presented him with was useless. Whatever’s in the file holds no value for him. And now, here’s Camden, being nice to him, feeling sorry for him. How fragile must he seem if even Camden—conniving, catty, horny Camden—has to treat him with kid gloves? He doesn’t want her pity. It’s ten times worse than her baffling flirtations, or even her blatant cruelty.

He scrambles to his feet, pushing her hand away. He feels, suddenly overwhelmed in his loneliness, like a flood of water has washed over him. No, not a flood. The whole ocean. He is inside the middle of an ocean, vast and crushing pressure from the unending water surrounding him.

Then he’s up and out of the basement, out of the house fast and the dog is there, waiting. He bends over so he’s down at dog-eye level. He considers pulling the dog in, holding it to his chest. He wants desperately to be close to someone. But not Camden, not his aunt, not any of his aunt’s dull, cow-eyed friends. He wants someone, or something that understands him. Then he’s mad for that, too. Mad that he’s been put in a position where he has to convince himself that dad and dog are interchangeable. Fuck the interconnectedness of all things, he thinks. If it were true, he could not possibly feel so lonesome.

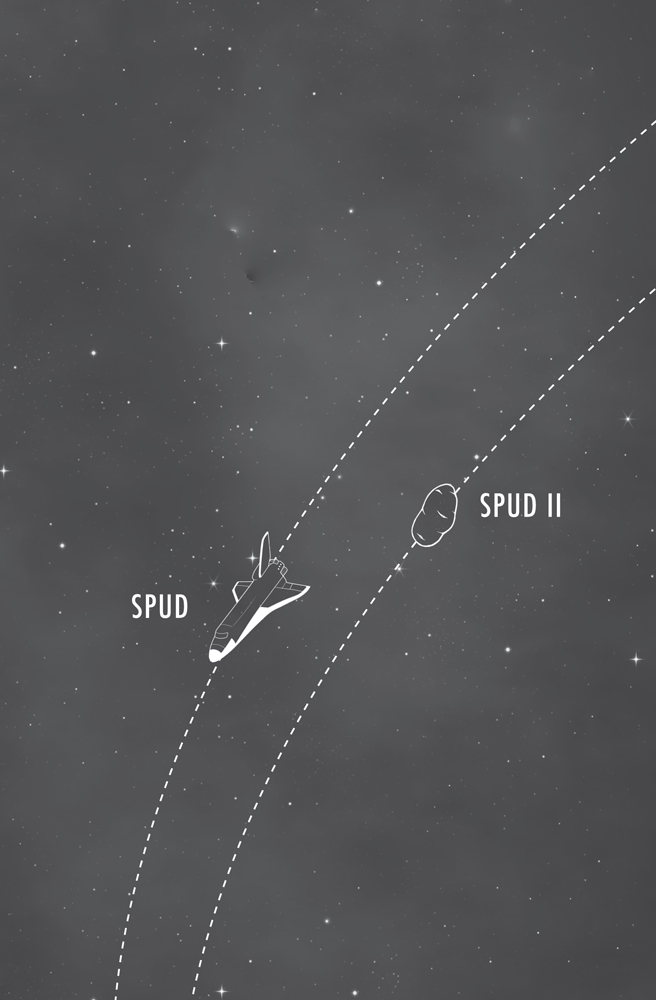

Really, he decides, the truth is the exact opposite. Nothing is connected and everyone is isolated, spinning quietly on their own private planets, victims of gravity and time. Any illusions of shared experience are just that—illusions. And on the rare occasion people in their sad, private planet bubbles do interact, it only leads to pain.

This idea comes as a relief.

Pain is better than loneliness, he decides. After all, he can choose to feel pain, and he can choose to inflict pain. This is a power he possesses. This is a power he, today, as a man, can exercise.

So, he doesn’t hug the dog. Instead, he slaps it in the face as hard as he can. For an instant, the dog just looks at him. Then it does what Spud knows any animal full of teeth and muscle should. It lunges.