July 15, 2090, Bainbridge Island, Washington

Caroline Olstead

On my way out for lunch, I stop by Angie’s toll booth to see if she wants me to bring her a sandwich. She says yes, but only if it’s egg salad or PB&J because she’s decided she’s a vegetarian again. Angie does this every couple of years. I tease her and ask if she’s been talking animal rights with Spud when I’m not around. I promise egg salad and remember that I’ll have to stop at the store myself since Spud never bothers to listen to messages and then I remind myself to chastise Spud for this when I get home.

I try to take a firm hand with him, like my mom did with Parker and me. It’s hard to know the right way to be with Spud, though. It’s a lot of pressure. Parker turned out to be a genius. An astronaut and a scientist. Spud’s got the same genes, so he’s got the same potential. There are so many ways Spud is already just like Parker. But I didn’t raise Parker. I wasn’t the one to make the hard decisions. So, when I’m stuck in any given situation, I think about what Mom would have done. I know sometimes I’ve got to step up and be the bad guy. In the situation of not returning a phone call and not going to the store, for example, Mom would have shouted loud enough to rattle Parker from whatever daydream he was in. You can be certain of that. So I’ll take the hard line with Spud, too. Even on his birthday.

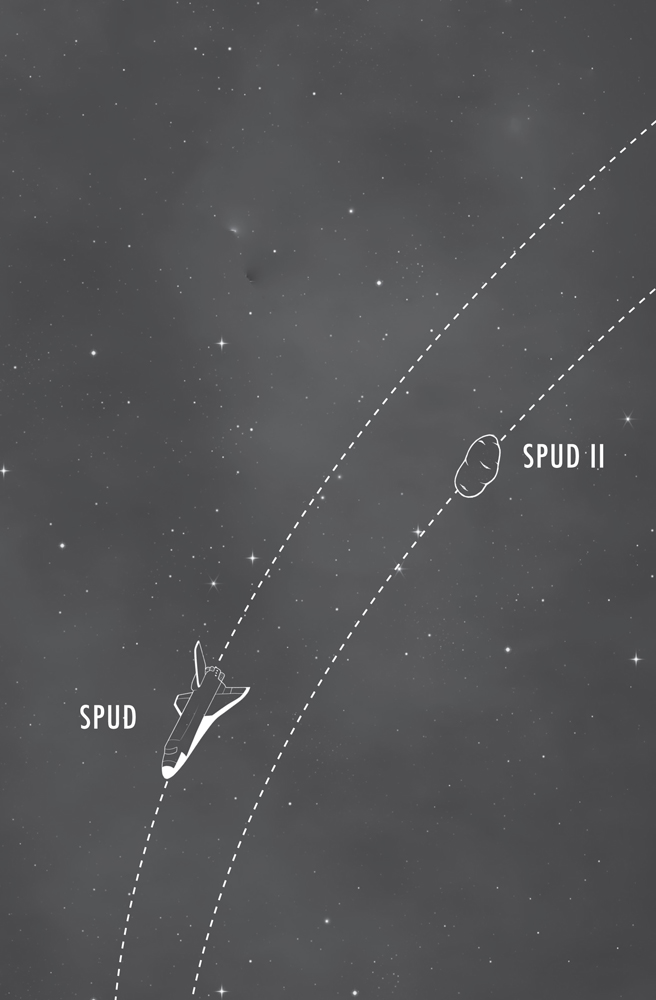

This isn’t to say I want Spud to turn out to be exactly the same person as Parker. Everyone, even a clone, has the right to be whoever he wishes to be—to make his own life. It’s up to Spud if he wants to be a scientist or not, an astronaut or not. That’s part of the reason I try not to linger on the subject when Spud asks about his daddy. I don’t want him to feel too influenced one way or the other. Like he’s got to carry on in the path of some dead man he’s never met.

All I mean about nurturing Spud is that Parker was so smart, and, at his core, so very kind. He really wanted to make the world a better place. Sure, we had our own challenges. When Mom was still alive, he was the good son, coming home for all the holidays. After she passed though, there was this sort of silence that cropped up between me and Parker. Not that we were mad at each other or didn’t get along. We just didn’t know how to be together. Like Mom had been the one thing we had in common and without her, we were strangers. He still came to visit, but less frequently, and I could tell it was mostly out of a sense of obligation, like he felt someone had to check in on lonely Caroline from time to time.

But the one thing he could get excited to talk about during those visits—if he did happen to be in a talking mood—was whatever research he was doing. He’d tell me about how marvelous the sea creatures he worked with were, and how studying them could tell humans all sorts of things about our own lives on Earth, both our past and our futures. He said knowing things like that could help us live better. I can’t pretend I understood all of it. But I believe he really was doing something important. Other people thought so, too. After he died, the government sent me all kinds of awards and commendations in honor of him.

And so I’m certain Spud could turn out like that, too. If only I knew how to encourage him in the right way, and to love him in the right way, I think he could grow up to use all his brains and his sensitivities and his intuitions for good. I wish I could ask Mom, of course. But I also wish I could ask Parker. To see what he would have to say about what exactly it is Spud needs.

I do my shopping quick, and in sort of a daze, thinking about all these things. I’ve got a lot on my mind today. But as soon as I come up the driveway to the house, I forget all of it, scolding Spud and making cake and egg salad included. Something’s wrong. First off, the stray pit bull that follows Spud around isn’t sitting on the steps. Second, the front door’s wide open. Of course I assume the worst.

I drop my groceries and charge in through the open door like a momma bear, hoping to startle whatever meth-head burglar’s in my house. But the only person there is Spud. He’s sitting at the kitchen table, hugging a bleeding arm to his chest. It looks like he’s been that way for a while.

“The dog bit me,” he says when he sees me.

“I can see that,” I say. I’ll be honest; I’m relieved. This is a Spud problem I know how to handle all on my own.

I bundle Spud’s arm up in a towel and call a cab to take us to the clinic, hoping they can patch him up well enough there and we won’t have to go across to the hospital in Seattle. The bridge is already absolutely miserable this time of day.

Spud bites his lip through the pain. I think of how Parker used to scream his head off every time he so much as scraped his knee. Then I think again about how there really are so many types of people Spud could turn out to be, regardless of his genes. There’s no predicting the ways any given situation will shape a kid and leave a mark on him, make him different from how he could have been otherwise. It’s scary, but it’s kind of a big fuck-you to those scientists at the University of Michigan and all the great plans they must have had for the clones. I can’t help but smile a little at the thought of it.

Tonight, I’ll tell Spud how much braver he is than his daddy was at his age. How much stronger. There are other little things like that, too. I should tell him more often, whenever I notice. The scar on Spud’s arm from the dog bite—that will be another thing. It’ll help remind him he’s his own man, even though he doesn’t know enough to think otherwise.