Chapter 3

The Olympic Dynamics

Up to this point, a basic historical backdrop has been introduced to explain the popularity and mystique of the Olympics for fans, athletes, and, ultimately, Olympic sponsors. With more than 2,700 years of Olympic history, the list of iconic athletes is long. Hundreds of thousands of athletes have competed, building and reinforcing the rich and varied traditions that comprise the Olympic ideal, so highlighting the very few always risks excluding other deserving performers. In the modern Olympic era, athletes have undergone a transformation from top athlete into star, a change made easier with the massive growth and popularity of twenty-first-century media and instantaneous communications. With the Olympic Games as a confirmed brand platform, the best athletes can create lifetime opportunities.

Athletes do not have to wait until after the Olympics to gain financial success. Many do so well before an Olympic victory, gaining sponsorship support when their skills and achievements bring them to national and international attention. Qatar is alleged to have paid the Bulgarian weight-lifting federation $1 million in 1999 for eight top weight lifters. Hossein Rezazadeh, a top Iranian weightlifter, was offered $20,000 per month, an exclusive estate, and an additional bonus of $10 million if he were to change nationalities and compete for Turkey’s Olympic team during the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens. He turned this generous offer down and still went on to win the gold medal, national pride outweighing financial gain.1

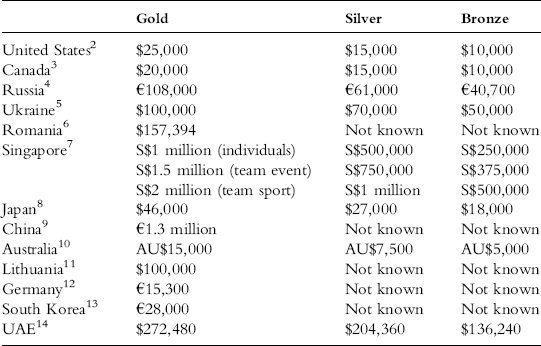

Should athletes succeed in winning a medal at the Olympic Games, their home countries often offer financial rewards. Table 3.1 provides reported data on the differing rewards paid to medal-winning athletes.

Table 3.1 Amounts Athletes Receive for Winning a Medal2

The figures in this table vary further within some countries, depending on the sport. Japan, for example, has paid, in prior Olympics, $37,750 for a gold medal in canoeing and $236,000 for a gold medal in table tennis. Russia has paid boxers and wrestlers approximately $100,000 for gold, whereas athletes in other sports receive $50,000 for winning plus an additional $50,000 if they break a world record. In Beijing, the United Kingdom paid track and field athletes £5,000 for gold, £4,000 for silver, and £3,000 for bronze, whereas judo competitors would have received £20,000 for gold, £10,000 for silver, and £5,000 for bronze. Gold medal winners in sailing would have received £10,000.15 In addition to the €1.3 million gold medal winners reportedly received in China, they also were given tax-free status on any other payments, and they received a kilogram of gold. This allowed many of their gold medal winners to buy houses, invest, and have a significant amount of financial security following their success. Romania’s gold medal gymnasts from the 2004 Athens Olympics each received two new cars, free apartment rent for life, and free university education.16

Does this harm the Olympic image of competitive purity? Conceivably, yes. But as discussed in the opening pages of this book, the ancient Greek athletes were not amateurs and were compensated for their performances. After the 1988 Olympics, the IOC decided to allow professional athletes to compete in the Olympics, so the concept of allowing only amateur athletes to compete has disappeared. Furthermore, for many countries, winning an Olympic medal is rare, and the winning athlete inspires national pride and increases recognition, even if it is for only a short period of time. There is a magnetic, captivating attraction to a medal-winning athlete that bestows a measure of glory on the country itself, just as corporate sponsorship of the games and athletes benefits companies. Many of the countries that pay medal winners substantial sums are still developing; consequently, there is a tremendous amount of national pride at stake if an athlete breaks through to win a medal and, thereby, brings added recognition to the country. Larger, developed countries like the United States pay relatively modest sums for winning medals, but athletes in the United States have the potential benefit of lucrative endorsement contracts with leading companies if their performances lead to winning Gold, Silver, or Bronze medals.

While Olympic athletes and their achievements are a source of pride celebrated by their home countries, the leap from athlete to marketable star who generates millions of dollars in financial support and a windfall for themselves and their sponsors has become most pronounced in the past 15 to 20 years. The implications are profound because athletes now have an additional motive to compete in the Olympics and, hopefully, win a gold medal—the potential for lucrative financial gain. However, winning a gold medal is a guarantee of neither long-term financial security nor professional success. Marketable success inevitably includes a backstory that reveals more of the personal sacrifice and challenge an athlete has endured to reach ambitious Olympic goals. If today’s formal business sponsorships and sophisticated marketing techniques were available to the ancient Greeks, one can easily imagine Milo of Kroton (recall that he was alleged to have eaten a bull) being a spot-on spokesperson for a favorite Greek restaurant or perhaps as an example for a public service announcement about the dangers of being alone in the woods (his unfortunate demise due to being eaten by wolves). Melankomas of Caria might well have had Greek fitness clubs and aerobic trainers for sponsors if such commercial enterprises had existed.

The Olympic athletes of the modern era enjoy a wide array of support choices from sponsors, donors, product companies, and more. This is not unusual in today’s sports world, where even athletes who don’t win championships make substantial endorsement income. Olympic athletes are different, however, because the title Olympian carries a special stature, and gold medal winners have an even more exclusive claim to fame. Such renown does not guarantee a future filled with lifelong riches and sponsorship deals. But during their Olympic years, top athletes can certainly enjoy life at the top of their sport as a star. Having star-quality branded athletes competing in the Olympics brings additional attention to the Games in terms of both viewers and general world of mouth, or buzz. Sports fans love the stars because these top performers give them somebody to cheer for enthusiastically or to root against with equal passion. Just as with product brands, a branded athlete acts as a filter for attention, separating them from those lesser known. Of course, when those Olympic surprises occur (as discussed in Chapter 8), the competitor vaults from obscurity to star in the process.

Companies that sponsor relatively unknown athletes early in their careers can find themselves in the fortunate position of vastly increased exposure from the media if the athlete succeeds. This can put the athlete in a position of power, even if only temporarily, since their increased fame gives them added leverage to renegotiate with the companies sponsoring them to increase their earning power based on their added value. Corporate sponsors must then decide whether to continue the sponsorship and, if so, how much it is worth. These are not easy questions since the athlete’s success may well be fleeting, yet dropping the sponsorship risks losing the increased interest from the public from which the company would benefit.

Exhibit 3.1 Athlete Sponsorships during Olympic Success

Michael Greis won three gold medals at the 2006 Winter Olympics in Torino in the biathlon (a sport combining cross-country skiing with rifle shooting) in the individual, mass start, and relay events. He was named German sportsman of the year. He went on to win gold in the 2007 and 2008 World Championships in the mass start and mixed-relay events, respectively. While the biathlon is not as widely covered as some other Olympic sports, his success attracted numerous corporate sponsors, including Adidas, Powerbar, Excel, DKB Bank, and Erdinger, a maker of nonalcoholic isotonic drinks.17

Michael Phelps is sponsored by Speedo, VISA, Omega, Powerbar, and Matsunichi. He also has appeared in TV shows and, in a nod to social responsibility, founded a youth swim program called Swim with the Stars and is deeply involved with Boys & Girls Clubs of America. In 2011, Bloomberg BusinessWeek.com’s Power 100 list of the most powerful professional athletes ranked Michael #12, behind #11 LeBron James (Miami Heat) and ahead of perennial stars Kobe Bryant and Roger Federer.18

Shaun White has won two Olympic gold medals. As of 2011, he has agreements for more than $10 million in endorsements, including American Express, Target, Oakley, Vail Resorts, Ubisoft, Burton, BF Goodrich, and Cadbury (Stride Gum). He is considered one of the most bankable stars in all of sports, a remarkable feat given the relatively narrow fan base snowboarding has, compared with more traditional sports. Bloomberg BusinessWeek.com’s Power 100 list ranked Shaun #2, behind Peyton Manning (Indianapolis Colts) and ahead of #3 Tiger Woods.19

Lindsey Vonn won Olympic gold in Alpine skiing in Vancouver in 2010, displaying fortitude and determination in the face of a significant and painful shin injury. She has garnered more than a dozen endorsement deals, including Under Armour, Head, Oakley, Alka-Seltzer, Procter & Gamble, Rolex, and Red Bull. In 2011, Lindsey was the highest ranked women’s athlete (#13 on the overall combined list), ahead of Serena Williams, on BusinessWeek.com’s Power 100 list of the most powerful professional athletes.20

Usain Bolt won three Olympic gold medals in Beijing in the 100- and 200-meter sprints and the 4 × 100 relay, setting world records in each event. He has endorsement deals with many leading companies, including Puma, Gatorade, Digital, Regupol, and Hublot. Usain’s deal with Puma was renewed in 2010 at a reported $5 million per year for three years, making it the most lucrative track and field endorsement in history. He was ranked as the most marketable athlete in the world in 2011 by SportsProMedia. Estimates of his 2011 net worth range as high as $32 million.21

A key challenge for companies is determining how long athletes will be at the peak of their abilities and success. Injury can end an athlete’s career well before a long-term relationship can be fostered. So why do companies take the risk to sponsor Olympic stars and pay often substantial sums, knowing there is a very real chance they may not win gold, may get injured, or may even find themselves in ethical trouble (such as performance-enhancing drug use) before the financial investment pays off? Companies sponsor athletes for many of the same reasons they sponsor events—they hope the positive qualities of that athlete will be associated with the company. The logic suggests further that fans of an athlete may become fans of the company sponsoring the athlete. A great deal of marketing work goes into making this association happen, and it usually takes a few years. But just as an Olympics sponsorship can pay dividends over the long run, so, too, can sponsoring an individual athlete.

Champion athletes have the same appealing qualities that attract companies to the Olympics—prestige, achievement, honor, competition—and this halo can follow them after they retire. Once their competitive years are behind them, they can and often do go on to earn significant incomes from motivational speaking, starting their own companies, serving their countries as politicians or similar leadership roles, and as recurrent spokespersons and sport experts with each subsequent Olympic Games. Companies continue to seek out former Olympic athletes to sponsor or to get involved in their business. Nike is well-known for attracting world-class athletes into their management ranks following their careers. Of course, Nike works with the athletes during the peak of their careers, as well as on new product design, marketing campaigns, and corporate goodwill, as do many of the other leading athletic companies in the world. More than 100,000 athletes have competed in the modern Olympics, so most are not stars. But many have gone on to highly successful post-Olympic careers.

The IOC continually reinvents the Olympic Games, adapting the event to meet changing sports interests around the world. Many new sports in the Olympics gained attention through mass media and popular culture, both of which help identify and popularize new trends, including extreme sports. The mix of sports is important to the success of the Olympic program, directly affecting fan and, consequently, corporate sponsorship interest. New sports attract new fan demographics and psychographics, which, for established sponsors such as the TOP partners, may increase their awareness, their reach, and even their sales around the world. Corporate sponsors also gain potential target (or niche) audience opportunities, which can be useful for testing new products and new grassroots marketing campaigns to a smaller market. New sports offerings can also enable a company to link newer products or a different product line altogether to the expanded fan base. Along with customer growth potential comes new partnership opportunities as well, because there may be companies with expertise in attracting a niche audience that could be useful to a large corporate sponsor. The sponsor gains more direct and credible exposure with the partner’s customers, and the partner gains from the corporate sponsor’s larger overall customer base.

The IOC regularly seeks balance between men’s and women’s sports to increase the appeal around the world. Once a sport has established a base internationally, with credible athletes and championships recognized by one of the 28 recognized International Federations (IFs), a large fan base, and a history of growing performance and interest overall, it may ultimately find its way into the Olympics. According to the July 8, 2011, edition of the Olympic Charter, the IOC reviews the entire program after each Olympiad. The review includes discussion of sports to add or remove. The total number of sports cannot exceed 28 in any Summer Olympiad (seven sports in the Winter Olympics), so the addition of a sport may also constitute removal of another if the maximum has been reached. As relatively simple as the decision process sounds, the decision itself is governed by a set of IOC bylaws and involves weighing complex data and insights about the current level of success for a sport. A majority vote then approves a program change for the next Olympics.22

As new sports are added, the chances of sponsors reaching new audiences increases. Plus, the Olympics maintain a sense of vitality and freshness while adding to the historical traditions of attracting the very best athletes. Table 3.2 outlines the new sports added since 1984.

Table 3.2 New Sports 1984–200823

| Olympiad | New Sports Added |

| 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo | Women’s 20-km race, Nordic skiing |

| 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary | Super giant slalom in Alpine skiing Nordic combined Curling (demonstration sport) Short-track speed skating (demonstration discipline) Freestyle skiing (demonstration discipline) |

| 1992 Winter Olympics in Albertville | Short-track speed skating Freestyle skiing with moguls |

| 1992 Sumer Olympics in Barcelona | Baseball Badminton Women’s judo |

| 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta | Beach volleyball Mountain biking Lightweight rowing Women’s football Professionals were admitted to the cycling events Softball (women’s-only sport) |

| 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano | Curling added Snowboard giant slalom Snowboard half-pipe Ice hockey for women |

| 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney | Triathlon Tae kwon do Modern pentathlon for women Weight lifting for women |

| 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake | Women’s two-person bobsleigh added Men’s and women’s skeletons (last time was 1928) |

| 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens | Women’s wrestling |

| 2006 Winter Olympics in Torino | Team pursuit speed skating Snowboard cross |

| 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing | Open water swimming Women’s steeplechase |

| 2010 Olympics in Vancouver | Ski Cross |

| 2012 Summer Olympics in London | No new sports added. Rugby sevens, squash, golf, and karate were under consideration but were not approved. However, both golf and rugby sevens will appear in Rio de Janeiro in 2016. |

| 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi | Women’s ski jumping Men’s and women’s ski halfpipe Mixed relay in the biathlon Team relay luge Team figure skating |

The 2010 Youth Olympic Games, for participants between ages 14 and 18, added a contemporary dimension to the Olympic brand, including the introduction of new sports and events, and new sports stars, targeted primarily to the youth. Modeled on the format of the regular Olympics, the YOG departs from its more familiar lineage with modifications in several of the typical Olympics sports. Since the YOG are new, changes in sports and disciplines are likely to continue in the years ahead in an effort to maximize appeal to the target youth audience while also staying true to many of the core activities found in the traditional Summer and Winter Games. In addition to sports, the YOG is distinguished from the traditional Olympic Games by its inclusion of programs in culture and education, designed to emphasize key themes in the world today, including healthy lifestyles, uses of social media, Olympic values, skills development, and social responsibility. For the first edition in Singapore in 2010, global media coverage was not as broad or timely as the regular Olympics, so awareness of the YOG was much lower than the regular Olympics. Table 3.3 describes the main changes in sports introduced by the YOG. Otherwise, the sports found in the traditional Summer and Winter Games still occur.

Table 3.3 YOG’s New Sports 201024

| YOG | Changes from Regular Olympic Games |

| 2010 Singapore | Eliminated synchronized swimming and water polo Added biking disciplines in mountain bike, BMX Eliminated biking disciplines in road, track cycling Changed basketball to three-on-three format |

| 2012 Innsbruck | Hockey added an individual skills challenge Mixed-gender ski teams in Alpine and cross-country events Mixed National Olympic Committees (NOC) teams in figure skating, speed skating, and luge |

Like many successful brands, the Olympic Games continues to change and innovate in an effort to stay current with global sports interests. The changes have come in many forms, from allowing professional athletes to compete to modifying the selection of sports to launching entirely new products like the Youth Olympic Games. This dynamism is important for keeping interest in the Olympic movement alive and vibrant from athletes, fans, and, of course, corporate sponsors.

1. What are the implications of paying athletes who win Olympic medals?

2. What are the risks and rewards companies face when sponsoring Olympic athletes?

3. How should companies evaluate potential endorsees?

4. How do the changes to sports in the regular Olympics affect the Games? How might the changes affect corporate sponsors?

5. Describe and assess the pros and cons of the Youth Olympic Games. What is done well? What changes would you recommend and why? What would the impact of your changes be on corporate sponsors? Athletes? International Federations? Sports?

Notes

1. NBC Sports, “Qatar Lures Athletes with Citizenship, Cash—Country Importing Athletes to Help Win Medals at Asian Games,” December 8, 2006: nbcsports.msnbc.com/id/16113525/.

2. Chris Isidore, “Time to Pay Olympic Winners: U.S. Medal Winners Get Prize Money, but Most Olympians Are True Amateurs Who Get Nothing for a Win,” August 20, 2004: money.cnn.com/2004/08/19/commentary/column_sportsbiz/sportsbiz/index.htm.

3. Jeff Lee and Gary Kingston, “Win Medals, Earn $$$; Canada Joins Other Countries with ‘Money for Medals’ Policy for Olympic Winners,” CanWest News, November 20, 2007; and Mark Brennae and Meagan Fitzpatrick, “Canadian Athletes to Get Cash for Olympic Success,” CanWest News, November 19, 2007: www.canada.com/globaltv/national/story.html?id=2a36c58a-ac62-4815-8d56-d815d71d9843&k=69958.

4. David Williams, “ . . . But Golden Wonders of China Will Be Set Up for Life,” Daily Mail, August 13, 2008; BBC Sports, “Russian Winners Promised Windfall,” July 12, 2000: news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/athletics/830528.stm.

5. “Sport Minister: Amount of Bonuses for Olympic Champions,” Ukraine Business Daily, February 3, 2010; BBC Sports, “Russian Winners Promised Windfall.”

6. “Comaneci No Longer Inspires Romanian Gymnasts,” ChinaDaily, March 27, 2008: www.chinadaily.com.cn/sports/2008-03/27/content_6569757.htm.

7. Singapore National Olympic Council, “Multi-Million Dollar Awards Program”: www.snoc.org.sg/mmdap.htm; Williams, “But Golden Wonders of China.”

8. “JAAF Offers Rewards for Medal Winners,” Japan Times, June 15, 2004: search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/so20040615a1.html.

9. Williams, “But Golden Wonders of China.”

10. Scott Taylor, “Slow Swimmer a Crowd Favorite,” Deseret News, September 20, 2000: www.deseretnews.com/article/195015385/Slow-swimmer-a-crowd-favorite.html.

11. Mark Baker, “Olympics 2004: For Some Athletes, behind the Medals Lies Real Gold,” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, August 6, 2004: www.rferl.org/content/article/1054208.html.

12. Williams, “But Golden Wonders of China.”

13. Ibid.

14. “UAE to Offer Cash Rewards to Medalists at Beijing Olympics,” Xinhua General News Service, July 30, 2008.

15. Dipesh Gahder, “Beijing Olympics: Athletes to Get an Alfa with Their Medals,” Sunday Times, August 13, 2008: www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/sport/olympics/article4449540.ece.

16. William J. Kole, “Olympics: The Spoils of Victory; Athletes Cash in on Olympics,” Herald-Sun (Durham, NC), August 19, 2004: findarticles.com/p/news-articles/columbian-vancouver-wash/mi_8100/is_20040819/olympics-spoils-victory-athletes-cash/ai_n51291814/.

17. Biathlon World web site: www.biathlonworld.com/en/press_releases.html/do/detail?presse=1334; translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=de&u=http://www.michael-greis.de/&sa=X&oi=translate&resnum=1&ct=result&prev=/search%3Fq%3Dmichael%2Bgreis%26hl%3Den.

18. www.olympic.org/uk/athletes/profiles/bio_uk.asp?PAR_I_ID=20272; www.facebook.com/michaelphelps?sk=info; www.michaelphelpsfoundation.org/about1.php; John Henderson, “Phelps Ready to Strike More Gold,” Denver Post, April 12, 2008: www.denverpost.com/sports/ci_8907515.

19. Jonathan Tait, “Shaun White Unveils Major Sponsorship Deal,” SportsPro, August 17, 2011; Tom Love, “Shaun White Endorses Chewing Gum Brand Stride,” SportsPro, March 8, 2011; ABCNews, “Olympic Endorsements: Who Will Cash In?” March 1, 2010: abcnews.go.com/Business/olympic-endorsements-cash/story?id=9961545.

20. ABCNews, “Olympic Endorsements”; BusinessWire, “Peyton Manning Tops Bloomberg Businessweek.com’s Power 100 Ranking of the Most Powerful Athletes in Sports,” January 27, 2011: images.businessweek.com/slideshows/20110124/power-100-2011/; Tom Love, “The World’s 42nd Most Marketable Athlete—Lindsey Vonn,” SportsPro, May 18, 2011: www.sportspromedia.com/notes_and_insights/the_worlds_42nd_most_marketable_athlete_-_lindsey_vonn/.

21. “Usain Bolt Signs New US$20 million Deal with Puma . . . Bolting to Bank,” Urban Islandz, August 24, 2010: urbanislandz.com/2010/08/24/usain-bolt-signs-new-us20-million-deal-with-puma-bolting-to-the-bank/; Tom Love, “The World’s Most Marketable Athlete—Usain Bolt,” SportsPro, May 27, 2011: www.sportspromedia.com/notes_and_insights/the_worlds_most_marketable_athlete_-_usain_bolt/; “Usain Bolt’s Net Worth 2011”: www.filipinoster.com/sports/usain-bolt-net-worth/.

22. IOC Charter, “Programme of the Olympic Games,” 80–83: www.olympic.org/Documents/olympic_charter_en.pdf.

23. IOC web site: www.olympic.org/Documents/Commissions_PDFfiles/Programme_commission/INFO_New_sports_sochi.pdf; “New Events for the 2014 Olympic Winter Games in Sochi,” BBCSport, July 8, 2005: news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/other_sports/olympics_2012/4658925.stm; IOC web site: www.olympic.org/uk/games/index_uk.asp; “IOC Approves New Sports for Beijing Olympics,” CBCSports, October 27, 2005: www.cbc.ca/sports/story/2005/10/27/iocmeetings051027.html.

24. IOC web site, “Youth Olympic Games”: www.olympic.org/yog-presentation.