Almost every day for the near quarter century that I’ve lived in Jerusalem, I’ve walked the main street of its western half, Jaffa Road, or the Jaffa Road, as it was known to earlier generations.

At first a pilgrimage and camel route, then a major commercial thoroughfare, it’s now a busy if bedraggled central artery that stretches from near the Old City’s Jaffa Gate, cuts across the new town, curves west through hills and wadis and across a plain till eventually it reaches the port of Jaffa. From there it once extended, at least in spirit, to the boats that would carry passengers and cargo off to, and in from, various far-flung lands.

As the road opened Jerusalem to the rest of the world and brought the world to it, so the history of the new city unfurled along this street. For all its fame, and its holiness to so many, Jerusalem had been until 1867—when the Ottoman sultan ordered the construction of that packed-sand-and-stone carriage track by forcibly conscripted bands of Palestinian peasants—little more than a hilltop village contained by a wall. A cramped, dark, diseased, and by most accounts foul-smelling place whose gates were locked at night, it had prompted the visiting Herman Melville, for one, to brood in his notebook about “the insalubriousness of so small a city pent in by lofty walls obstructing ventilation, postponing the morning & hasting the unwholesome twilight.”

With the presence of the toll road that stretched from the city to the sea, however, a new kind of movement into and out of those claustrophobia-inducing fortifications became possible, as did a new sort of freedom. And when a central station for carriages plying the Jaffa Road was established just beyond the Jerusalem gate that bore the same name, the city spilled forth once and for all. Greeks and Germans, Arabs and Armenians, Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews alike opened hotels and kiosks, travel agencies and photo studios, coffeehouses, liquor stores, a telegraph office, souvenir shops, rug dealerships, a pharmacy, a bakery, outlets for carpentry and building supply, even a theater that featured tightrope walkers and performing bears. Foreign consulates, banks, post offices, and eventually the municipality itself also moved past the gate, and within a short while the crowded area just outside the walls had been transformed into a makeshift town square described by one native son as nothing less than “The City.”

In 1900, in honor of the twenty-fifth year of the reign of Sultan Abd el-Hamid, the authorities erected a red-and-white candy-striped public fountain in the midst of this multilingual, multitudinous crush. An ornate stone clock tower followed seven years later. All self-respecting Ottoman cities featured such clocks in their central squares, and Jerusalem’s was a point of pride to those who lived there. Forty-five feet tall, perched atop the Jaffa Gate, it was a sign of civic progress, of Ottoman patriotism; it bound Jerusalem’s citizens to the other citizens of the empire, and in ways both figurative and literal it represented the arrival to this very old place of a new way of telling time. It also functioned as a kind of beacon. Soon after it was built, the municipality strung its high outer walls with glowing gas lamps. Visible even from villages far off, the tower looked, wrote another native son, like a lighthouse.

* * *

“What I see, what I see,” began the Galician-born Jewish novelist Joseph Roth, using the words as a kind of mantra or incantation as he set out to describe the lazy walk he took around Berlin one May morning in 1921. Attempting to recount a walk through Jerusalem, c. 2015, one needs to vary this slightly and say: “What I see, what I don’t see.”

As I stroll the main street of the city I’ve called home for most of my adult life—a city that has held me in its grip, delighting, infuriating, bewildering, surprising me since I first encountered it—I’m considering both what meets the eye and what doesn’t.

While every urban area evolves architecturally with the years, Jerusalem has a funny way of burying much of what it builds. Captured and recaptured some forty-four times by different powers throughout its long history, the city is as renowned for the structures razed there as for those it has retained. And so it is that the current town stands, as one excitable nineteenth-century commentator put it, “on 60, 80, or even 100 feet of ruins! You begin digging in the streets of Jerusalem, and you come upon house-tops at all varieties of level under ground! It is probable that we have there traces and remains of older and more numerous generations than in any other city under the sun.”

But the archaeological debris isn’t all ancient. Almost immediately after General Edmund Allenby dismounted his horse and marched on foot through the Jaffa Gate on December 11, 1917, declaring “Jerusalem the Blessed” subject to English martial law, for instance, the British authorities began making plans to destroy that lively Turkish town square. The squeamish, pious military governor, Ronald Storrs, found the ramshackle buildings and chaotic scene there distasteful, and he developed a particularly visceral antipathy toward the Ottoman clock and its gewgawed tower. He claimed it “disfigured” the gate, and arranged for it to be, as he put it, “bodily removed.” A blockier and more plainly British sort of timepiece and tower, “shorn of the more offensive trimmings” of the earlier version, was then built at a less fraught though still central spot on the Jaffa Road, just to the northwest of Sultan Suleiman’s medieval walls. The architectural equivalent of a pair of sensible shoes, this went up in 1924, two years after Britain received a formal Mandate from the League of Nations to govern Palestine, and it served both to tell the hour and to make plain who now controlled the holy city—which the British had recently declared the country’s capital for the first time since the Crusades. The corner then known as Post Office Square was soon rechristened in the name of Allenby.

After a decade, that English clock tower, too, was knocked over (not because of conquest but to ease traffic flow around the curved prow of the new Barclays Bank and city hall that had just gone up on that corner), but Storrs never did manage to bulldoze the bazaar just outside the Jaffa Gate and replace it, as he’d yearned to do, with a pristine garden loop around the Old City. He left town, the British left the country, the Mandate ended, and in 1948 a high concrete and corrugated tin barrier was thrust up right beside Allenby Square, creating a crude but effective border between the new state of Israel and Jordan. That ugly wall was a finger jabbed in the eye of this once integrated and integral site. It was in fact only with the Israeli occupation and annexation of East Jerusalem in 1967 that Storrs’s half-century-old scheme for a greenbelt was realized and, declaring the city “united” under Israeli rule, the authorities demolished what the Bauhaus-trained chief planner of the project would refer to dismissively as “the dilapidated structures, shacks and rubble” and “the more visually offensive shops” around the Old City walls; a national park was set down in their place. Meanwhile, the now clockless spot opposite the walls, so recently redesigned and renamed for its conquering British hero, was redesigned once more. Today the small plaza set on the tense if invisible dividing line between the city’s Jewish West and Arab East boasts a dry fountain, several squat olive trees, a line of struggling dwarf cypresses, an unremarkable set of curving stone steps, and a new name: IDF Square.

* * *

When I contemplate what I see and don’t see on Jaffa Road, though, I’m thinking not only of such burials, erasures, and attempts to mark political turf by means of culturally symbolic architecture and hastily rewritten maps. I’m also musing on the multiple unrealized versions—and visions—of the city that exist and have existed in the minds of those who’ve felt compelled to try to build here, in all senses of that term.

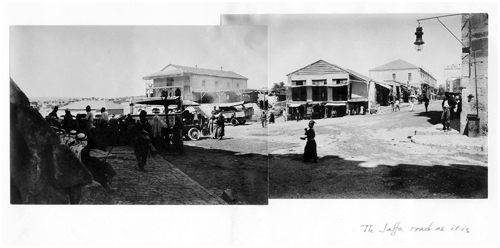

At around the same time that Joseph Roth was observing the beggars and waiters, the horses and cigarette ads of the Kurfürstendamm, the British architect, town planner, and Arts and Crafts activist Charles Robert Ashbee—a disciple of William Morris and employee of Ronald Storrs—was, as Jerusalem’s first-ever “civic adviser,” striding the same main street that I do daily, snapping pictures and scribbling notes as he imagined a radical transformation of this area in both spatial and social terms: “The Jaffa Road as it is,” he labeled one panoramic photograph, which shows a blur of locals in kaffiyehs, head scarves, and fezzes lolling before a pile of watermelons and a cluster of ramshackle stands and shops.

He then rendered a neat pencil sketch of the same landscape, minus its saggy red-tile-roofed buildings and heaped fruit. In their place, his drawing shows an evenly staggered, spic-and-span progression of traditional domed structures, with a few neatly dressed natives marching purposefully by. This he titled “The Jaffa Road Market as I want it to be.”

That may sound childish, perverse, or like mere wishful thinking, but Ashbee understood better than most the very steep challenges he faced in attempting to remake or reform this city according to his own romantic worldview. Although he lasted in town only briefly and, it might be argued, didn’t really understand the context in which he was working, he felt as passionately aspirational about its future as so many others have who’ve devoted their lives to the place. Yet for all the energy he invested in its development, its civic improvement, its beautification, he also recognized the poignancy—even futility—of such efforts and the almost chronic way that Jerusalem has of frustrating hopeful expectations: “It is,” he wrote, “a city unique, and before all things a city of idealists, a city moreover in which the idealists through succeeding generations have torn each other and their city to pieces.”

* * *

And then there’s what I do see:

Just a hundred yards or so from the start of Jaffa Road, the sleek, porthole-punched tower that the once celebrated German Jewish refugee Erich Mendelsohn designed as the Anglo-Palestine Bank is among the most expressive and subtle public buildings in town. When it was completed, in 1939, it was the tallest “skyscraper” in Jerusalem at a looming seven stories, but it wore then and still wears its height with unusual grace, as the soaring perpendicular of its main section is grounded dynamically by the low horizontal block at its back. As he did with all of his buildings, Mendelsohn planned this one with an acute awareness of the physical setting (a busy street that seemed to demand a building of clean, unfussy lines and a certain mute but impressive presence) and of topography (a steep incline to the rear). He also meant it—as he did all his designs—to be a bold challenge to his peers. When it opened, the bank would be the national headquarters of the most important Jewish financial institution in Palestine, but Mendelsohn claimed inspiration for this decidedly modern and Zionistic undertaking from the shapes of local Arab buildings. He did this often, and that tack got him into frequent aesthetic and political hot water throughout his Jerusalem years.

Next door to the former bank (now an Israeli government ministry) is the city’s main post office (still a post office), another striking building that I pass by and take a certain solace from almost every day. A more monumental and symmetrical structure than Mendelsohn’s, it was completed a year before the bank and was designed by the exceedingly gifted Austen St. Barbe Harrison, then the chief architect of the British Mandatory Public Works Department. Private, canny, and refined, Harrison left England for the East as a young man and never looked back; his vision for his own buildings and for the city was informed by his deep knowledge of Byzantine and Islamic architecture, as well as a decidedly nonpartisan, even pacifistic relationship to the then already serious local ethnic strife. Though Harrison designed the post office as a proper English governmental edifice in its scale and its accoutrements, he also quietly borrowed multiple elements from those traditions he’d absorbed while living and working throughout the Levant—from the alternating light and dark stripes of Syrian-styled masonry to the geometrically ornamented panels of the massive wooden double doors. The outline of Harrison’s building remains as grand as it ever was, though for some fifteen years now a certain feeling of constriction has taken hold around it, since all but one, or one-half, of those impressive sets of doors have been locked for security reasons, and visitors are funneled into the handsome old post office by means of a narrow metal detector. The same is true of Mendelsohn’s former bank, the dignified doorway of which is now also cluttered with security equipment.

Not all of Jerusalem’s modern buildings are so well guarded as these two prominent structures. If I walk northwest along the same road, moving toward the central area known as Zion Square, I’ll soon reach yet another building the view of which somehow always startles me for its strange, almost spooky dignity—this, despite its location, opposite a large and fetid garbage compactor, usually swarming with the mangiest of stray cats. On the corner of Jaffa Road and the street formerly known as Queen Melisande Way—now named for another queen, Heleni, a first-century Iraqi convert to Judaism—this far more eclectic commercial and residential building features three stories of playfully harmonious arabesques: horseshoe arched windows, jagged crenellations, and a wide façade inset with panels of once luminous, now grime-covered tiles made by the Armenian master potter David Ohannessian, who worked in Jerusalem throughout the Mandate. A mishmash of businesses crowds the downstairs floors, changing hands and nature often (at the time of this writing, the storefronts are occupied by a popular café, a nail salon, a fluorescent-lit twenty-four-hour grocery, a nook of an old-world tailor shop, a nondescript hotel, and a self-declared “hot dog toast” take-out place with a plastic sign announcing its cryptic yet somehow appropriate name, only in lowercase English, “after”). Meanwhile, the dirty, graffiti-smeared foyer leads to what seem, from the sorry state of the exterior and the junk piled on its balconies, run-down apartments and hotel rooms. When it was completed in the late 1920s, the property of a well-to-do Christian Arab from the village of Beit Jala, this building was considered the height of style and was known around town as Spyro Houris House, after its architect—though that fact has long ago faded from the memory of almost all.

Who were these three very different men—Erich Mendelsohn, Austen St. Barbe Harrison, Spyro Houris—and what led them to conceive these buildings and the other remarkable structures they designed around town? What did they see here and what did they want to see when they walked the dusty streets? In twenty-first-century Jerusalem, they’re barely remembered, and the city or cities they had in mind are vanishing as well.

Beginning with the rocky topsoil and digging its way down, this book is an excavation in search of the traces of three Jerusalems and the singular builders who envisioned them.