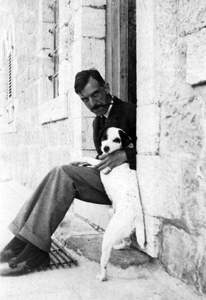

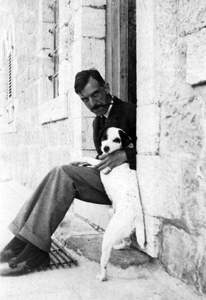

Happy to be alone in his ledge-like little garden, which commanded a sweeping view of the Old City walls and the flat, stepped roofs of the village he knew by the biblical name of Siloam, Austen St. Barbe Harrison sat and sketched. He was only thirty-two years old and already the reluctant veteran of several war zones, a fundamentally peaceful person whom peace seemed chronically to elude. But here in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Abu Tor—under a cypress, with his white dog, Bogie, sleeping beside him, the door to his small wallflower-laced stone house propped open to let in the breeze—the chief architect of Palestine’s Public Works Department appeared to have found, or created, a quality very much like it.

The most private of public servants, Harrison knew precisely what he enjoyed and possessed an almost otherworldly ability to order the space and hours around him so that he might gently but firmly obtain that. On this particular occasion, in late October 1923, for instance, he’d requested a four-day furlough from his government-issued drafting table because he wanted to stay home and draw the village below. This leave was, he wrote his younger sister Ena, back in England, “most grudgingly agreed to by the new Director of Public Works,” the kind of man “who can get no kick from anything in life” outside of the office. “He almost had a fit when I told him how I intended spending my time.”

Though he led what he himself called “rather an Eremetical Existence,” Harrison insisted that “I am really a sociable person despite appearances. Only I must be able to get away from society which suffocates me.” Luise Mendelsohn would later describe him as a friend to her and Erich and “a very sensitive artist,” though she’d add, pointedly, that “He did not like women and when I asked him to a cocktail party at the windmill he answered my invitation by saying that he never went to Cock or Hen parties.”

Partygoer or no, he was devoted to his friends—several formidable females among them. (The adventurer, Arabist, and travel writer Freya Stark would become a confidante and regular correspondent after the two met in Cairo in 1940.) And later in life, Lawrence Durrell would dedicate Bitter Lemons, his memoir of the turbulent years he spent in Cyprus, to Harrison, his neighbor and regular companion there in the 1950s. Although Durrell quotes yet another English friend, Harrison’s architectural partner in Cyprus, Pearce Hubbard, as calling him “an awful recluse … one wouldn’t come so far from the haunts of man if one were a gregarious or clubby type,” the author of The Alexandria Quartet understood the role that sustained friendships played in Harrison’s quiet existence. “For him too,” writes Durrell, of Harrison, “the island life was only made endurable” by visitors from beyond and so he had “built himself a khan or caravanserai on one of the main highways of the world” into which he welcomed these widely wandering kindred spirits.

Jerusalem may be dry and landlocked, but it’s also an island, and many of the aesthetic ideals that Harrison would eventually bring to bear on his secluded Cypriot life he’d taught himself while residing in this simple three-room house in Abu Tor. For Harrison, though, it really didn’t require much study, since many of these habits came to him naturally. Durrell would later remember him as representing “that forgotten world where style was not only a literary imperative but an inherent method of approaching the world of books, roses, statues and landscapes.” In Cyprus, Harrison would transform a stable-like hovel into his home “with a tenderness and discretion” that made “the whole composition sing.” The house seemed to Durrell “a perfect illustration of the man,” with its book-lined walls and glowing icons, its point-arched loggia and lily pond that served as more than a mere function of good taste and instead embodied “an illustration of philosophic principles—an illustration of how the good life might, and how it should, be lived.”

So it was in Jerusalem as well, where, working with his typical patient resolve, he’d made every inch of this unpretentious house’s vaulted ceilings and stone floors his own. He’d scattered carpets and hung woodcuts on the whitewashed walls, lowered a piano into a pit in the main room, and carefully arranged a large blue-velvet-covered couch, a few oil lamps with muted orange shades, candles for reading, several armchairs, and other chairs of rush and painted wood. He’d also set his beloved gramophone into a deep window niche, from which at all hours Couperin, Bach, and Puccini spilled into the Palestinian night.

As he ordered his home and its simple yet precisely chosen and placed furnishings, so would Harrison order each building he planned in Jerusalem. From the angular ornamentation of the ventilation slits at Government House to the shady cloisters at the archaeological museum and the square carvings on the wooden doors at the central post office on the Jaffa Road, each architectural element was an expression of his keenly absorptive sensibility and of those philosophic principles Durrell describes. Having internalized the airy yet compact feel of his house in Abu Tor, he’d set out to replicate something of its cavernous, thick-walled quality in almost all his Jerusalem plans. “There is a particular kind of rubble vaulting peculiar to this country which not long before the war was everywhere employed and today is still employed outside the cities,” he wrote in one official memo concerning the design of a major government building. “This vaulting merely whitewashed or painted is so pleasing to the eye that any kind of decoration or ‘finish’ becomes superfluous.” Ironically enough, given his taxpayer-funded position and the ostensibly impersonal nature of his Palestine commissions, the unfussy symmetries and clean proportions of his humble peasant-built dwelling in Abu Tor would serve as silent inspiration for almost all the public buildings he’d leave behind him there. And so, in the most essential way, would his composure, his solitary nature, and his unflagging capacity for perspective, in every sense of the word.

While he has been forgotten by most of those who today pass through and use his Jerusalem buildings, each remains a “perfect illustration of the man”—part of his archive, and of the city’s own.

* * *

Besides providing him architectural inspiration, the Abu Tor house served as a refuge—not just from the chatty distractions of tea parties and receptions but also from the grueling job he’d taken up the year before.

Fresh from planning the reconstruction of towns and buildings in the war-devastated regions of Macedonia and then in Thrace, and around the area of the Gallipoli battlefields, where his work plotting settlements for refugees was abruptly cut off by the outbreak of yet another war (this one Greco-Turkish), he’d answered a call put forth in 1921 by the first high commissioner of Palestine, Herbert Samuel. In code, Samuel had telegraphed the secretary of state for the colonies, Winston Churchill, and demanded EARLY SELECTION AND DESPATCH of FULLY QUALIFIED ARCHITECT FOR SERVICE WITH PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT JERUSALEM. The appropriate candidate would be PRACTICAL ENERGETIC MAN PREFERABLY WITH SOME EXPERIENCE OF BUILDING WORK ABROAD IN CLIMATES OR COUNTRIES SIMILAR TO PALESTINE … POSITION CONSIDERED BEST SUITED FOR UNMARRIED MAN BETWEEN THIRTY AND THIRTY FIVE …

With his experience of building work abroad in climates similar to Palestine, the eminently practical, energetic, and most unmarried Harrison, age thirty that year, fit Samuel’s description to an uncanny T. Although he was essentially, even implacably, British—he counted Jane Austen as an ancestor and himself as her namesake, took tea, smoked a pipe, and ate porridge for breakfast till the end of his days—he had turned his back on England as a young man and had no desire to return. With the exception of a few months in 1922, engaged in what he called “Delhi work” at Sir Edwin Lutyens’s London architectural office (where he assisted with plans for the imperial Indian capital as he beefed up his colonial CV) and a short stint in the late ’30s designing the buildings of Oxford’s Nuffield College (his original spare, flat-roofed plans for which were rejected by the donor as “un-English” and later adapted resignedly by Harrison “on the lines of Cotswold domestic architecture”), he would spend most of his life far to the southeast of it. In the process, he became a kind of honorary Levantine as he rooted himself in a series of modest but elegantly appointed dwellings in Palestine, Egypt, Malta, Cyprus, and Greece. However British Harrison may have been, the much-modified Nuffield commission was his single attempt at building in Britain. And for all the respect he’d come to command as an architect in Palestine and among a small circle of English architects, he’d remain mostly unknown—then and now—in his native land.

Some of the discomfort he felt among his countrymen was social: “I admire English people so much provided I am not mingled with them,” he wrote. “When too close in the mass they bring out my worst instincts.” But his attraction to warm foreign lands derived not so much from the urge to flee England as from his strong feeling for the spirit of each of these olive-eating places, taken singly and as a region. At one point, contemplating the fact that he might be compelled to live and work in the country of his birth, “a cold shiver” ran down his back. “How can I be happy,” he mused, “in a place where the sun does not always shine.”

The landscapes of the Mediterranean had riveted him from the first moment he encountered them as a recent veteran of various dressing stations and bivouacs on the Western Front. Having refused to apply for the officer’s commission that was nearly a given for young men of his class, he served as a stretcher bearer in some of the grislier battles of the war, dragging bodies through mud and tending to the wounded. It was “the only job in the army I can undertake with a good conscience,” he wrote in the midst of the fighting to his worried mother—though even then he wondered aloud “whether I would not have been more honest if I had simply claimed to be, what I really am, a ‘conscientious objector’ and gone to prison.”

Perhaps it was the memory of these scenes of modern devastation he’d recently witnessed around the European trenches that made the ancient ruins he encountered in the Mediterranean seem so vital, and so achingly familiar. For a man devoted to a life of construction, he had a distinct fascination with wreckage. In letters from the front, he’d described, for instance, the “abject desolation” surrounding one famous battlefield—unnamed, it seems, because of the censor: “Everywhere were trenches, barbed wire and acres and acres of shelled ground now partly hidden by rank grass and made bright with poppies and cornflowers.” Nearby, a French village whose “name was once on everyone’s lips” was now “only a mass of bricks.”

On his first trip to Greece, in 1919, a certain melancholy echo was audible as he described being alone in nature with “the awful silence, the uncanny stillness” and wandering “among the massive walls of old Eion, now but an isle in a morass.” Sometimes the links between these haunted vistas were more direct: “Curiously enough,” he wrote of a late-afternoon walk on a mountaintop near Salonika, “the wood at the summit with the clouds entangled in the branches of its trees brought back to my mind that eventful day three years ago when at dawn we searched Louzy Wood [Bois de Leuze] in the Somme, enveloped in fog, for the wounded of the Division we had that night relieved.” The same way the weird hush had marked a lull in the battlefield bombardments, this Macedonian reverie soon faded ominously as he “watched the sun sink into the sea turning its customary blue into golden shimmer.” Dusk descended quickly in these parts, and hurrying down the mountain, he wondered whether he’d reach Salonika before nightfall. “I quickly lost sight of the mule track which I had hoped to follow and stumbling over rocks and bushes drew close, as luck would have it, to one of the many flocks of sheep and goats that wander about the mountain. A stranger in the twilight hours is not welcome to shepherds so the guardian of these sheep did not recall his dogs who, as soon as they saw me began to howl. I threw stones at them but that only made them fiercer and for a few minutes I quite expected to be bitten. I put on a bold face and doubling my pace left them still howling and growling behind me.”

The difference now was that—angry canines aside—he was in love with what he was seeing. Setting out on foot or donkey to survey possible building sites, or “crawl[ing] up and down” the streets of Salonika “noting and measuring bits of churches and walls and watching the people in the gay and busy bazaars,” he declared that he’d “never … in all my life been so consciously happy.” He seemed to have felt himself newly alive, delivered from the horrors of war and sprung free from the various strictures that bound him back in England. He was also, critically, drawn to the “irregularities of Byzantine construction,” which he found remarkable; in Constantinople Hagia Sophia’s proportions and immensity dazzled him. The countless mosques he visited there awed him as well, and he described the markets of that city as “a wonder. Imagine a number of connected streets of great length covered by barrel-vaults and lined with four thousand booths.” Village inns, stone fountains, minarets, crumbling monasteries, sheikhs’ tombs, caravanserais, old Turkish and Venetian forts, half-buried Doric columns, and fading inscriptions on the floors of ancient temples also fascinated him, even as their presence stoked his romantic conviction that joy and beauty were more poignant for being so fleeting: “This sense of exquisite pleasure cannot of course last; who indeed would want it to last,” he asked rhetorically in the midst of one of these idylls.

But architecture almost always gave way in this landscape to archaeology. Asked by the Macedonian director of antiquities to sketch a prehistoric dwelling he’d uncovered in one of the tumuli of Salonika, Harrison found himself contemplating the shattered vases, ornamented gold leaf, and human teeth that emerged from the cemetery of what appeared to be the buried town of Therma. On another outing with the same official, he visited the locked fourth-century church of Saint Demetrius, in the part of Salonika that had burned in the fire that swept the city in 1917. The church was still standing, but its marble revetments were badly damaged, and the roof had tumbled to the floor. Its elaborate mosaics “calcined and wrecked” by the flames that raged there just two years before, the devastated building might as well have been the scene of some ancient sack or conflagration, gradually reverting to nature and now property of the rooks who nested noisily within its blackened walls.

* * *

When in Greece, Harrison had set his sights on finding further work there or in the Near East. Even as he’d been drawing up plans for the repair of various “destroyed cities” in Thrace and Macedonia, he’d installed himself at the British School in Athens, where he lived after leaving Salonika and, in his free time, devoured every book and article he could find about Byzantine and early Muslim building. This new Eastern obsession didn’t, meanwhile, dampen his abiding passion for classical construction—not surprising for an architect whose training had centered on the monumentally rational Beaux Arts style in vogue when he was studying first as a college student in Canada and then in London.

But analyzing such stately symmetries in a classroom was one thing; experiencing them viscerally for himself was another. On a 1920 trip through Rome, he was smitten by the city and the buildings that so grandly constituted it: “I had become a little tired of Italy as presented in the thousand and one architectural text-books which I have been obliged to study…,” he wrote in a letter to his father. “This very expression ‘Eternal City’ and phrases such as ‘See Rome and die,’ ‘All roads lead to Rome’ etc., made Rome seem commonplace to me. Now I know that they are true. Rome is truly marvelous … See Rome and Live would be more appropriate. Since the War material interests have made great inroads in me; but now I am once more wildly enthusiastic about Architecture. I have been rushing about, sketch book in hand, seeing hundreds of buildings and it is useless to catalogue them.”

Oddly enough, in light of the prodigious imagination, time, and care that Harrison would pour into Jerusalem—all of his major work would take place there in the course of the fifteen years he’d spend in the city, and he would eventually come to be viewed by local architectural historians as the representative builder of the British Mandate, “almost the sole author” of its official designs—he’d leave no such record of his initial encounter with the place. Much later, having left it, he’d look back wistfully and describe “descend[ing] the stepped suk which leads from the citadel of Jerusalem to the Great Mosque and stand[ing] for the first time on the threshold of the Haram ash Sherif” as “one of those experiences that a man of sensibility treasures all the days of his life.” The contrasts between the “religious calm” of the space and the “secular bustle” all around, as well as the beauty of the Dome of the Rock and the “thought provoked by passive contemplation of this historic and holy ground” combined in a way that was “so absorbing that he is likely to be reduced to awed silence.”

Perhaps this hushed sense of wonder accounted for his taciturnity on arrival. Of his letters that would survive into the next century, the first postmarked from the city was written in July 1922. Addressed to his mother, it mostly contains chitchat about the weather, the terrible food included as part of his room and board at the Old City’s Austrian Hospice, the government’s panicked reaction to a strike by local Arabs against the impending Mandate—they’d called in extra troops who “march through the streets every day, blowing their bugles. This is intended to impress the Arabs who respect the British but hate the growing ascendency of their Israelite cousins”—and the fact that his dress suit and sports coat were missing from his luggage.

Or maybe he had expended his store of lavish adjectives on those lands where he was just stopping over. Now he was ready to hunker down to sustained work in one spot, applying all the lessons he’d learned about Byzantine buttresses, four-square Turkish reception halls, and water-burbling Andalusian courtyards to a city capacious and world-weary enough to take them all in.