At the same time he was planning Government House, Harrison nursed an architectural secret—“a real secret not to be spoken,” as he confided to his mother six months before the quake. Even in the days just after the earth shuddered, and he described to her the widespread destruction brought on by the shifting of the local ground, his thoughts remained fixed on the building he wanted more than any other to construct, though the particulars were still “highly confidential.”

Since coming to Palestine, he’d learned all kinds of things that fascinated him—about rubble, twig, and packed-mud vaulting; about the various grades and colors of Jerusalem stone and the different styles of its chiseling; about the madafeh (reception room) and the mastabeh (living space) of the traditional peasant home; about modern art and ancient relics, Armenian tiles, and the alternating light and dark masonry stripes known as ablaq. He had also learned much more than he would care to know about politics and pettiness and about what he continued to refer to as “propaganda”: “How heartily sick I am of political propaganda vested as aesthetical criticism,” he’d write a close friend in a moment of especially pronounced disgust. In this top secret case he was well aware that “all kinds of strings will be pulled to prevent me from doing this big job.” Ever a master of scale, he had measured the situation correctly.

It was a big job, the biggest he’d reckoned with so far. Declaring that “the past of Palestine is more important to the world than the past of any other country, and there are no monuments more precious than those which reveal to us the past of this land toward which all civilized people turn with reverence,” the American philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. had confidentially pledged $2 million to build an archaeological museum in Jerusalem. Rockefeller had been persuaded by the highly enterprising, small-town-Illinois-born, Yale-and-Berlin-educated Egyptologist, archaeologist, philologist, and founder (with Rockefeller’s funds) of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, James Henry Breasted, that the holy city—and indeed all of humanity—was in desperate need of a new museum. The building that then held many of Palestine’s most important artifacts was a poorly lit, run-down, and overcrowded three-room house, while countless other precious relics simply lay outdoors, exposed to the elements and at risk of damage or theft. And beyond the need to rescue all these local objects and provide them with a proper home, Breasted was intent on establishing a center in the Near East where he might further realize his own lifelong dream of a “historical laboratory,” devoted to the study of no less than “the Origin and Development of Civilization.”

Breasted tended to think in grand if not grandiose terms. The first American ever to receive a Ph.D. in Egyptology, he’d coined and popularized the term “Fertile Crescent” to refer to the semicircular sweep of land that runs from the Nile to the Mediterranean to the Euphrates and was, in his words, “the earliest home of men.” And his scheme for a Palestinian museum and research institute dedicated to the analysis and display of Near Eastern artifacts was in fact a severely scaled-back version of the thwarted scheme that he and Rockefeller and Rockefeller’s Beaux Arts–inclined architect, William Welles Bosworth, had outlined for Egypt’s King Fuad several years before, in the form of floor plans and a comprehensive program for a $10 million museum and archaeological institute in Cairo.

As described in the appeal they offered up with great pomp to the Egyptian monarch in 1925, this investment would be “a gesture of friendliness and appreciation from a citizen of the great Democracy of the West, profoundly interested in that remote spiritual ancestry which is common both to your Majesty’s subjects and to the American nation.” Bosworth’s previous work included the restoration of the Palaces of Versailles and Fontainebleau, as well as the design of the neoclassical Cambridge campus of MIT and the formal gardens of Rockefeller’s Westchester county estate. And again in the Egyptian case his patrons encouraged the architect to think in majestically massive terms. The sumptuous structure he meant to erect on the banks of the Nile was intended, according to Breasted, its intellectual mastermind, to be “perhaps the most magnificent museum in modern times.” Its exterior would be built of solid ashlar masonry, with a portico held aloft by a dozen forty-five-foot-high columns “which it is hoped may be monolithic shafts of granite from the same Assuan quarries whence the ancient Egyptian architects hewed their granite, from the days of the first pyramids to the vast obelisks of Luxor and Karnak.”

These fanciful plans for the celebration of ancient Egyptian artifacts, though, hadn’t taken into account the needs or desires of modern Egyptian human beings, and when King Fuad and his prime minister actually absorbed the details of the “gift” the wealthy American and his ambitious house Egyptologist were offering, they declared the conditions “absolutely unacceptable” since “they infringe upon the sovereignty of Egypt!” They had a point. According to Breasted and Rockefeller’s terms, the museum was slated to be directed for thirty years by a commission made up largely of American, British, and French “men of science” and not by Egyptians themselves. Europeans and Americans would administer the endowment that would support the museum and institute—possibly forever. At a time when the king was reckoning with a serious popular nationalistic movement and threats to his authority, they were essentially asking him to cede control of Egypt’s antiquities to a group of Western interlopers. They were also strongly suggesting he agree to the version of history they planned to put forth in foreign-tourist-friendly exhibits that would outline what their prospectus called “human development” as it proceeded “from primitive savagery” to “a highly refined culture … through a magnificent culmination to a decline which eventually resulted in European supremacy and … in European leadership of civilization.”

Breasted’s condescending attitude toward the present-day place and its people extended to Fuad as well, whom he considered “a vain and self-conscious Oriental.” He hoped “to intoxicate” the king by donning a top hat and full evening dress and presenting him with an elaborate color brochure outlining the project. The vision put forth in this lavish watercolor-illustrated publication would, Breasted assumed, “give him such a pipe-dream of Arabian Nights possibilities” that “we shall be able to stampede him.” His Highness was, in the end, not so easily stampeded, and the idea of Rockefeller’s Egyptian museum came crashing down with all the force of one of those huge Karnak-worthy shafts of granite.

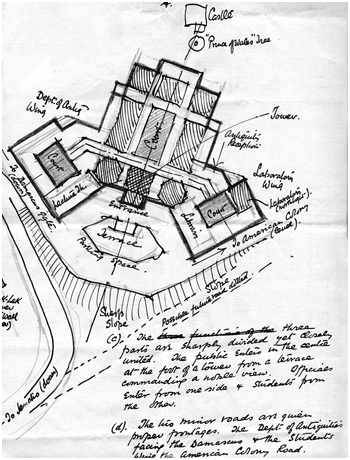

In the wake of the collapse of these flamboyantly neopharaonic plans—and in keeping with the far humbler Palestinian setting—the Jerusalem museum was meant to be a much simpler affair, and at first Breasted proceeded cautiously, securing a $20,000 grant from Rockefeller to pay for initial sketches and an option on the eight-acre plot of land that Harrison and his friend John Garstang, the department of antiquities director, had scouted, just to the northeast of the Old City walls, in the area known as Karm ash-Sheikh. Harrison’s first designs for the Rockefeller-funded museum were all drawn up in secret in the spring of 1927 and approved enthusiastically by the Americans. They praised his approach to “fundamental matters of circulation, lighting, and external architecture,” and came around to agreeing with his own sense that the site required an asymmetrical building, as opposed to the symmetrical structure he had first designed.

Breasted had sent him a pile of floor plans of various American museums built in an imposing Beaux Arts mode—from New York’s Metropolitan to the Field Museum in Chicago and the Cleveland Museum of Art, each with its Grecian columns, sweeping marble staircases, and grand rotunda or great hall, designed to dazzle. But Harrison had his own distinctly earthbound sense of what form he thought the Jerusalem museum should take: “the Romanesque such as one finds in Sicily. Not that there is any reason that Sicily should be followed except that there as here in Palestine East meets West & in both countries building materials are alike.” He had also included a boxy tower as part of his design, since—as he wrote in neat longhand to his Chicago correspondent—“it is traditional here to give important buildings towers, as you know.” Without it, the building would be somewhat hidden from the new parts of town; a tower would also provide excellent views of the Old City. Breasted agreed, and friendly discussion ensued about the precise shape of the tower, the angle of the museum’s façade in relation to the Old City walls, and so on and cordially on, with Harrison declaring in his typically self-critical way “how pleased I am that you have discovered some merit in my scheme. Its defects are so glaring that I missed the merits.”

But as they entered into sustained conversation about all the geometrical, topographical, and stylistic possibilities (“I am writing this letter, in order that you may not receive a shock when you see the plans I have now in hand,” Harrison cautioned Breasted in September 1927, after substantially revising his preliminary design, “for I have returned once again from asymmetry to symmetry…”), and even after Rockefeller agreed to devote a full $2 million to the project, they kept the proposal for the museum under wraps for diplomatic reasons. Though the budget for this structure was appreciably smaller than that for the Egyptian museum, the terms that Rockefeller and Breasted were offering the Mandatory authorities were also appreciably more respectful than those presented to King Fuad. The government of Palestine would need to agree to expropriate and contribute the Karm ash-Sheikh site and to remove the slaughterhouse and municipal incinerator located nearby, but there was no mention of foreign archaeologists assuming control of local antiquities. According to the terms of Rockefeller’s gift, the museum itself would be explicitly given to “the Palestine Government for all future time without any conditions whatever as to its future management.” As one SECRET AND CONFIDENTIAL letter from Breasted to Plumer had it: “The reason for this arrangement is, of course, obvious: the proposed Palestine Museum is to remain in English hands.” Or, as one of Rockefeller’s other advisers put it in a blunter and more gleeful note to his boss, “What a satisfaction it is to deal with the English after trying to deal with other races!”

Breasted certainly seemed to consider Harrison his cultural equal. When the architect came back around to a symmetrical plan, for instance, the Illinois Egyptologist appeared delighted—as much by Harrison’s straight-shooting English character as by his structural savvy. “The man who has the courage to change his opinions more than once if he is sure that they are each time based on the facts,” he proclaimed, “is the only man for me.” He sounded relieved to have at long last found someone in this dusty, sunbaked part of the world who spoke his language.

* * *

Beyond the lofty geopolitical reasons for discretion about the museum plans, closer to the ground, Palestinian politics also played a role in the secrecy that first surrounded the project. Once Rockefeller’s grant was made known, Harrison realized there would again be “a howl and suggestions that there should be a competition” to choose the architect, just as a howl went up when he was appointed to build Government House. The country’s many newly arrived Jewish architects in particular were upset that they hadn’t been considered for the work. But he did at least have the trust of Plumer (who hadn’t yet announced his imminent retirement); the high commissioner told him that “despite the clause in the letter covering the gift to the effect that the architect shall be one of eminence,” the job was his. And this made way for an unusual admission by Harrison of his own superior expertise. “Without any prejudice,” he confided to his mother in November 1927, “I think he is not wrong in making this decision. I feel I know more about building in Palestine than any other man and what I don’t know about museum design is something I can learn.”

No sooner had he pronounced what sounds uncharacteristically like a boast, though, than his usual skepticism and self-deprecation kicked in: “That is what has been decided but … I may, after all, not get the Job. Why Lord Plumer has such faith in me I cannot imagine.”

He was, it turns out, at once right and wrong. On the one hand, he was wrong to doubt himself so, since he did finally get the Job—a Job for which it seemed he’d been preparing since his earliest days as an architect of the archaeological, or archaeologist of the architectural. His friend Garstang had resigned as director of antiquities in 1926, and late the next year, his successor, Ernest Tatham Richmond—himself an architect and a specialist in Islamic building with a long and complicated connection to Palestinian politics and planning—reported that Harrison had “happily gained the confidence of the authorities both in America and in Palestine [and] is thoroughly qualified to undertake this work.” At around the same time, ample correspondence crossed the ocean to this effect, with Breasted declaring his great satisfaction with Harrison to Plumer and Plumer declaring to Breasted the same. Once the job was definitively Harrison’s and the veil of silence had been lifted, he was ordered to travel to London where he hired three assistants to help him plan the museum.

But he was very right about the howling that ensued as soon as all this became public, since his trip prompted what he called “a rather vicious campaign in the Jewish press here” attacking the authorities for importing British architects and for not holding a competition. “They say I was sent to England because I know nothing whatever about museums and that I recruited men who did.” He had, he added, also received letters “from more than one Jew apologizing for this campaign.” But it was a distracting way to work.

There were, meanwhile, other distractions—and other diplomatic dances that also needed to be performed, since in this context the placement of every stone wall and clerestory window became a political two-step. Though Harrison’s plans had been approved in principle, Richmond and the other members of the local committee charged with overseeing the museum’s construction now began to question the presence in his design of a tower. As Richmond wrote in a January 1928 letter to Breasted, many of the committee members considered it an unnecessary expense. Moreover “on the aesthetic side it is, as I am sure you will agree, desirable to regard the design not only as an isolated architectural unit, but also in relation to its surroundings, which include to the immediate south the Holy City itself.”

Benign as the complaint sounds and friendly as Harrison and Richmond generally were with one another, this appears a perfect instance of the “political propaganda vested as aesthetical criticism” that made Harrison so “heartily sick.” Given the fact that the museum, and with it the offices of the Palestine Department of Antiquities, would be built on a slight rise above the Old City, the committee felt that the tower threatened to dominate. Such a suggestion would, Richmond wrote, “surely be unfortunate; it might even be looked upon as a breach of architectural good manners, for the Museum will be the servant, as it were, of the great historical and archaeological interests symbolised by the Holy City, outside the walls of which, it should, I suggest, stand certainly with dignity, but also with becoming modesty.” In a more personal aside, Richmond—a recent and very devout convert to Catholicism—admitted that in his opinion “Jerusalem has enough towers already.” It would be, he believed, “a pity to add to them, or to appear to join in a competition for unnecessarily attracting attention.” (Looking back, it’s worth noting that Richmond was registering his distaste for such structures at the very same time that the American architect Arthur Loomis Harmon—whose New York firm was then also busy designing the Empire State Building—was drawing up and getting approval for plans to build Jerusalem’s fanciful new orientalist extravaganza of a YMCA, whose most prominent feature was its 150-foot-high “Jesus Tower,” by far the tallest structure in town. Located across the street from the King David Hotel on the road then known as Julian’s Way, and funded primarily by a wealthy family from Montclair, New Jersey, that building was also constructed with money donated by Rockefeller.)

According to Richmond, Harrison was willing to reconsider the museum’s tower, though shortly after returning to Jerusalem from his trip to London, Harrison wrote a bit grumpily to his mother to describe how he was “fighting the local committee” about it and to complain that they’d gone directly to Breasted without consulting him: “They don’t like to oppose outright for they are not sure of themselves and they fear to place themselves in opposition to the donor so they wriggle. I am wriggling too.”

But Breasted—at the safe remove of Chicago and not nearly so entwined in Jerusalem’s sticky webs of political and religious intrigue—strongly defended Harrison to the committee and insisted that “the self consistency of Harrison’s designs as a whole should be the determining consideration, rather than whether Jerusalem already possesses a sufficient number of towers.” Furthermore, without a vertical like the one that Harrison had planned, the long low outline of the rest of the building would seem “extremely tenuous, depressed and totally lacking in any uplift.” Harrison had deliberately “given his building very reserved and austere lines, exclusively structural in character. Hence the need for something more.” Perhaps, Breasted suggested, they could reach a compromise by simply lowering the height of the tower instead of removing it entirely.

Off the record and in response to Breasted’s defense, Harrison thanked him for “all the pleasant things you have found it possible to say about the plans.” For now he preferred not to comment on the tower question “as it is sub judice,” but he would, he wrote, “like to congratulate you on having so fully comprehended what is at stake. I have given a great deal of thought to the matter and am still doing so.”

Yet even as they were all busy peering upward, and imagining the tower and its effect on the sacred skyline, Harrison was also forced to lower his gaze and contemplate the facts already on the ground, and beneath it.

* * *

No lot in Jerusalem is ever really empty. Karm ash-Sheikh certainly wasn’t, and if anything, the architectural challenges posed by this small swatch of land made it (and still make it) a fraught microcosm of the entire fraught town.

In addition to the rocky contours that swelled below it, the irregularly curved roads that ran alongside it, and its close proximity to one of the world’s most famous city walls—as well as many of the holiest spaces and structures anywhere on earth—Harrison’s museum would need to delicately work around a building that had long existed on the site. This was a crumbling two-story villa built in the early eighteenth century by the aristocratic religious scholar and leader Sheikh Muhammad al-Khalili when he came from Hebron and planted his land with a vineyard and an orchard of fig, olive, almond, and apricot, and which Breasted and the antiquities authorities insisted on calling “the Crusader Castle.” (It seems Godfrey de Boullion and his troops did camp out in this area before they took Jerusalem in 1099, though they had nothing to do with the construction of the gracious if slightly ramshackle stone building that now sat upon it and that was known to the locals as Qasr ash-Sheikh, the Castle of the Sheikh.) A massive pine tree also marked the spot, and legend had it that more than two hundred years before, when al-Khalili arrived there, he brought its seedling in his turban. Fixed on a slightly different cast of historical characters, the English knew the pine as the “Prince of Wales Tree” since the soon to be King Edward VII pitched his tent beneath it when he visited Jerusalem in 1862.

Whatever the villa and pine were called, both were literally central to Harrison’s decision to revert to a symmetrical plan, since “by Mr. Rockefeller’s special request” the tree must be “retained in an organic relation to the Museum,” according to one account, and the tree itself seemed already to exist in organic relation to the qasr. While Harrison warned Breasted that “I do feel that it would be easy to pay to these objects too great a respect,” he had a very clear idea of how he’d like his design to interact with these elements that predated it. The old building “externally is so modest that I think reverence rather than apotheosis is indicated.” And “the life of a tree is limited alas & I do not think that the future of this building ought to be too greatly influenced by this one. I propose,” he wrote, “simply to honour it by placing my axis so that it passes through it.” Seasoned gardener that he was, he’d be proved right when some sixty years later the tree would die and be cut down—though as long as Harrison’s building stands, the central line of his museum plan will preserve its memory like that of a phantom limb.

More difficult to design around than these visible traces of former lives planted on the site were the hidden traces of the former lives that lay beneath it. In late June 1928, Harrison was overseeing the digging of trial pits in preparation for the laying of the museum’s foundations when the workers unearthed an expansive Roman and Byzantine graveyard.

The cemetery wasn’t a total surprise. As early as 1874, the French archaeologist and orientalist Charles Clermont-Ganneau had commented on and published his description of this “group of sepulchers, cut in the rock,” complete with a map. (“There have been found in them…,” he wrote, “quantities of bones, broken pottery, ‘boxes’ in soft stone, and an ear-ring in gold…”) His words were reproduced in the widely circulated Survey of Western Palestine, published ten years later, and the citation dutifully copied out in various letters between Breasted and the antiquities authorities as early as 1927, though their presence seems not to have been considered a problem when the site was chosen for the museum. Now, though, as the workers started to dig, those few bones and broken pots quickly multiplied and soon gave way to a vast trove of objects and skeletons. “We have,” Harrison reported to Richmond just a day into this procedure, sounding at once frustrated and awed by the way the ghostlike past had again wafted up to haunt the present, “found a grave in practically every pit dug.” Within a week, the workers had filled baskets with tens, then hundreds of pins and beads, potsherds and lamps, “skulls and many human bones,” in the words of one antiquities inspector, “with the arm bones crossed diagonally and the skulls between, evidence of careful burial.” And just as carefully as they were set in the tombs all those centuries ago, these remains would now need to be exhumed with exacting attention.

So extensive was this field of scarabs and skeletons that a month after the digging began, Harrison called a halt to the foundation work “pending further investigations.” As is often the case in Jerusalem, the dead had overwhelmed the living. It would take almost a year for the excavating to resume and another nine months before he could report to his mother that “the foundations of the Museum are well in hand,” though “a heavy downfall of rain has not been helpful.” Other developments also slowed the work: Plumer had left and Chancellor arrived and impatiently awaited the construction of the new Government House, which the authorities gave political priority over the museum. Because of the riots of 1929, work in Harrison’s office had ground to a halt for several months, and it took some time for things to return to a kind of normal.

Against this backdrop of bones and bloodletting, Harrison was meanwhile in the peculiar position of creating his very own remains, in stone and on paper. The latter will require excavation as well, buried as their traces eventually are in the archive of the museum built over the graves.

No trowels or baskets are necessary. Years later, perched on a plastic chair before a laptop computer, I open a fraying folder and read a letter dated February 1, 1929, from A. St. B. Harrison to Mr. Richmond: “There is a matter about which I intended to speak to you when last I saw you. It is possible—I am afraid probable—that someone will have to lay a foundation stone. God knows I would much rather this were avoided. I must however be ready for any emergency.”

It’s odd and more than slightly eerie to be thumbing through these pages while sitting in the space labeled “Record Room” on Harrison’s floor plans. As he penciled in those letters, had he ever imagined that his records might one day be deposited in this very room? “The position for such a stone I have already considered. I ought however to search for a suitable stone (possibly a piece of Hoptonwood from England) & have it carefully lettered. I cannot do anything, however, until I know what is to be inscribed. Brevity is very desirable. We don’t want to emulate the inscriptions in London public conveniences.”

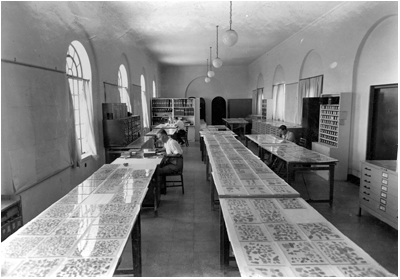

Whatever his vision for the future of the building, he can’t possibly have conceived that the same room would become world-renowned in the 1950s as “the Scrollery,” the long, light, and airy Jordanian chamber in which the Dead Sea Scrolls would first be pored over and parsed. The ancient past would have a famous future here, even as his own modern moment would already be fading from view. “What I am afraid of is that one day someone from the Secretariat or elsewhere will have a brilliant idea & I shall be asked to have a stone ready within twenty-four hours or less & as I am rather sensitive about lettering, I should consider this disastrous.”

He might not even recognize his architectural handiwork in what would become the cubicle-and-tin-shelf-crowded Israeli office where, more than another half century after the fragments of the scrolls are arrayed under glass across long tables here, I find myself typing his words into a computer file to the sound of Hebrew telephone chitchat and the synthetically sweet smell of hot instant coffee.

Which details will be remembered? Which will fade? Disappear?