That the museum filled with relics would one day also be a relic may or may not have occurred to the fez-, fedora-, and turban-wearing guests seated before the raised wooden platform at the ceremonial laying of that foundation stone in the summer of 1930. Or perhaps the assembled dignitaries, under all their varied hats, truly believed that the building’s importance would endure for ages—together with the British Empire and Palestine itself. Posterity was certainly on the minds of those in charge. Why else the emphatic fanfare of the carved inscription?

THIS STONE WAS LAID BY LIEUTENANT-COLONEL SIR JOHN ROBERT CHANCELLOR, G.C.M.G, G.C.V.O, D.S.O. HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY’S HIGH COMMISSIONER AND COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF IN PALESTINE, ON THE 19TH DAY OF JUNE IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD MCMXXX

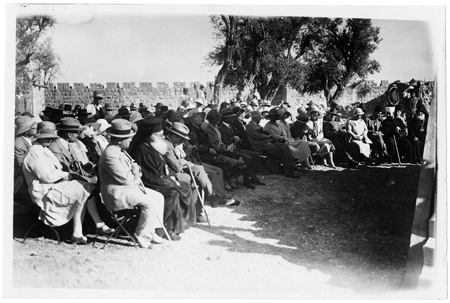

Why else set down with inching exactitude and why later store the plans for every stage of the so-called Order of Procedure, from the instant when His Excellency mounts the platform by the north steps to the speech by the director of antiquities and its translation, to the speech by His Excellency and its translation to the point when the director of public works hands the lead box filled with “Palestine coins” to His Excellency, His Excellency places the box in the cavity, the director of public works hands the trowel to His Excellency … and so on and on, exceedingly stiffly, until that moment of high if not exactly spontaneous climax when His Excellency taps the stone, the director of public works hands the level to His Excellency, His Excellency levels and declares the stone truly laid, and (after yet another translation) leaves the platform by the south steps?

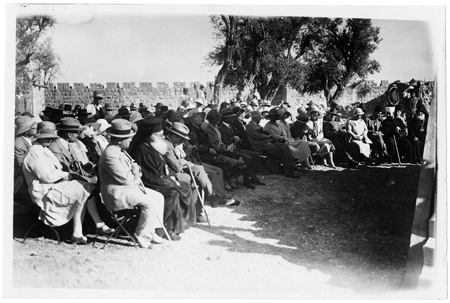

Why else preserve Rockefeller’s Western Union telegram to Chancellor offering CORDIAL CONGRATULATIONS and wishing FOR THE MUSEUM A LONG LIFE OF USEFUL SERVICE? Why record and retain the list of those invited to celebrate this burial that follows all the exhumations? Dr. Albright, Signor A. Barluzzi, Dr. E. L. Sukenik, Dr. & Mrs. Canaan, Mr. D. C. Baramki, Dr. L. A. Mayer, Miss Garrod, the Archminadrite Kallistos, Jacob Spafford, Adil Eff. Jabre … Was there, in the urge to keep and catalog these piles of inky ephemera, some flickering awareness of just how fleeting the moment was? In all their ethnic, religious, and linguistic variety, the guests represented a hybrid and relatively peaceful Jerusalem that may already have seemed to some of them—given the violent explosions of the previous summer—to be dangerously fragile if not under serious threat. Though if they were anxious, they didn’t show it. The photographs of the crowd that had gathered on folding chairs before the Old City walls that sunny Thursday afternoon convey an air of almost drowsy calm.

Whether later glued into Harrison’s personal photo album or sent on with captions to Breasted in Chicago for preservation at the Oriental Institute archive or mailed to Rockefeller’s Manhattan office in the Standard Oil building for his secretaries to deposit in fine wooden cabinets—all the black-and-white pictures will fix in time, as in amber, that sense of the day’s overwhelming placidity, even boredom. The professors and priests, the judges and journalists, the mufti, the mayor, the Jewish Agency representatives, the Arab Executive representatives, the bishops under their pointed hoods, the women in their cloches and chic high-heeled shoes (they are wives, secretaries, one formidable schoolmistress, a pioneering archaeologist or two): all sit side by side and turn their faces upward, smiling faintly as His Excellency proclaims it—according to the typed copy of his remarks, later filed neatly on several continents—“a great privilege to be present today to lay the Foundation Stone of the Palestine Archaeological Museum.”

Everyone, that is, except Harrison, who detested official functions but who apparently couldn’t avoid this occasion, meant to honor the construction of what Chancellor assured the crowd in the same speech would be “this beautiful building.” In the photos of the ceremony that will be so carefully held for decades to come in those far-flung albums and archival boxes, the architect’s tall, lanky frame and close-cropped head appear in fragmentary profile at the very back corner of the platform. Averting his gaze as the speeches are made and the stone is lowered on its winch, he stares off to the side or down at the floor and looks intensely uncomfortable, as though he’d rather be almost anywhere but here.

* * *

If the ceremony made him miserable, it was no reflection on the museum itself, which—thinking back after its completion and his hushed 1937 flight from Jerusalem—he’d describe as “the one work in Palestine with which I was connected which has given me some measure of satisfaction.”

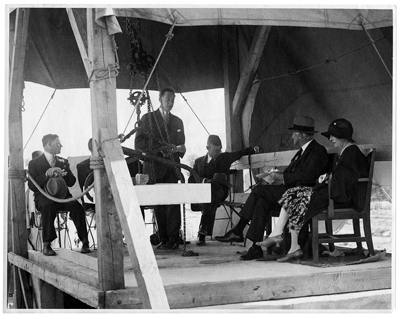

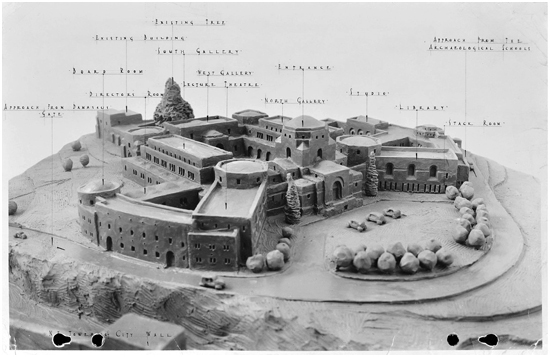

Understatement aside, he’d been waiting for years to build such a thing, more than any other of his designs the product of his very own time-traveling, quietly kaleidoscopic imagination and forceful will, and one whose funding by a wealthy private foreign investor had protected it from some of the grosser compromises he felt had been foisted on him in other, bureaucracy-bitten, government-sponsored contexts. As it emerged in his final plans and in the small ceramic model placed on display beside the platform at the June ceremony—as well as in the finished building itself—the museum would be, in a subtle though palpable sense, the pale stone embodiment of all the architecture he had absorbed in this part of the world, and of all the architecture he most admired. With its curved barbican and squat octagonal tower, its arrow-slit windows and wider, arched windows, its cave-like cloisters, sun-bleached courtyards, staggered rooftops, and multiple low-domed cubes, his design borrows elements from Islamic tombs and Crusader forts, Byzantine churches, Palestinian peasant houses, and even the Alhambra. In the process, it makes a mysterious if somehow inevitable whole of these disparate parts, both suggesting and transcending the cultural context of each squinch and every column. It’s almost as though Harrison had drifted to sleep and dreamed this building, which, for all its gravity, also conveys a certain sly and even sphinxlike wit. The building seems to be symmetrical but isn’t, quite. Its careful geometries give the illusion of matching one another, but discreet differences proliferate throughout, as architectural half rhymes. With its play of light and shadow, its strict lines giving way to gentle arcs and rounded vaults, its hidden nooks and wide-open spaces, it takes shape as a kind of whispered riddle—somehow akin to Jerusalem itself.

More than paying homage to any one tradition or style of building, the museum soundlessly echoes the ramparts and domes of the Old City right beside it, but it transforms the chaotic, competing turrets and towers of the actual jumbled and often angry landscape into a single harmonious whole. The museum isn’t exactly utopian—of no place—since its rubble vaults and lemony stone mark it absolutely of this place. But the building is, in a way, aspirational, as it suggests Harrison’s own private vision of the city—not exactly as it was, but as it might, in a better world, be.

He knew as well as anyone, of course, that in order to build such an immaculately serene structure, with its shades of the heavenly Jerusalem, he’d need to reckon with the demands of an all-too-earthly town. Delays were by now so commonplace he barely bothered to note them in letters, though Breasted had to keep careful track, since Rockefeller’s grant was due to expire if it wasn’t used by the first of January 1931, so he and more than one high commissioner needed to politely and repeatedly ask the patron for extensions. (The 1929 stock market crash had also added a newly nervous dimension to Rockefeller’s participation, as his own fortune, though still substantial, was badly hit.) Just a few months after moving into Harrison’s brand-new Government House that year, Chancellor left Palestine and was replaced by Sir Arthur Wauchope, an old friend of Breasted’s, who was, the Egyptologist insisted, “in no way whatever to blame” for the slowness of the building’s progress. Besides the discovery of the graves and the 1929 “outbreak … wherein the Arabs massacred the Jews at many points in Palestine,” construction had been further bogged down by the difficulty of finding a sufficient quantity of acceptable stone. Although Harrison and the highly cultured Scottish Wauchope would seem temperamentally poised to become natural allies, the architect sounded both wary and weary at the prospect of having to learn to please yet another high commissioner—the fourth to have ruled Palestine since his arrival. “I hope only that he is not a Tartar,” Harrison wrote his mother, a few weeks before His latest Excellency took over. “He is a bachelor … He is said to be musical and artistic. But I have learned that this may mean many things. He is said to have a passion for enjoying his house. This too may mean many things.” And in fact the slight Scotsman with the silver hair and the fine taste would soon gain a reputation around town for ranging all too widely. Much as Erich Mendelsohn admired Wauchope, he’d be remembered later by one British official for “his intolerance, his charm, his bursts of temper, his calculated shrewdness, his inconsistencies,… [his] many kindnesses … [He] was a living example of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”

But before reckoning with the high commissioner’s seemingly split personality, Harrison had to contend with the shortage of quality stone. First he managed to piece together small lots from seventeen different sources, then the government opened a quarry near Nablus specifically for this project, and he and his assistants had to modify their drawings to make the best use of that supply. As always, the all-American Breasted also blamed cultural difference for the “astonishing amount of time required for … construction,” offering that “it is not a usual thing to put up a building of this character in a country as primitive as is the case here … [so] some delay might have been expected.” Moreover, “our British friends in Palestine are, like all their countrymen, slower and more deliberate than we are.”

Harrison had in fact been working doggedly—as had a crew of some seven hundred local laborers who’d managed by June 1932 to make use of three thousand square meters of walling stone, a thousand tons of cement, and two thousand five hundred cubic meters of sand. According to one of Harrison’s progress reports, filed that month, they’d almost completed the lower floor, and work on the upper ground floor was proceeding “rapidly,” with some of the vaults already in place. He was eager to oversee the completion of the building’s carcass by January 1934, with the “major part of the finishing trades” wrapping up their additions by the middle of that year. With this in mind, a “considerable quantity of Walnut has already been selected in Syria and brought to the site, where it is now being cut and stacked.”

Unmentioned in all these crisply worded accounts of the precise amount of stone, wood, and cement required to erect and properly outfit the museum were calculations of a less architectural, more flesh-and-blood sort: namely, which population would finally outnumber the other in Palestine? These days Jews from Germany and Austria were entering the country in droves, much to the dismay of the native-born Arabs. Even though the government had established certain immigration quotas, in late October 1933, further demonstrations protesting the arrival of so many Jews gave way to further violence. A deputation of local Arab leaders arranged to meet with Wauchope to air their complaints and again demand a representative government. According to one newspaper account, they “stated that the basic fear in the Arab mind was that the Jews would obtain supremacy in Palestine to which Sir Arthur replied that there was no need to fear since he was ruling the country with equity.” The next month, Harrison adopted the same breezily dismissive tone as he assured his mother that “there is no cause at all for anxiety. The rebellion is over. I had neither so amusing, nor so exciting a time as in 1929. In the last troubles, you will remember, I was the target of Jews; in this, of the Arabs. They ambushed five of us in a car and fired at us: but luckily missed. Once again I had to search my elderly landlord for arms.” Politics, meanwhile, now permeated every stage of the building process, from the appointment of architects to the hiring of laborers. The relatively pastoral Eastern backwater where Harrison had first begun work as a young architect was now the epicenter of one of the world’s most relentless life-and-death national struggles—a struggle in which he himself had no particular stake, though staying detached was itself, he’d come to realize, a highly dubious prospect. Fairness of the basic sort in which he believed seemed challenged at every turn.

Not only was ethnic tension mounting daily, so was Harrison’s strong sense that Wauchope did not value his work. (“As usual, he gives me credit for nothing,” he wrote Ena, “and finds everything I do amiss.”) The high commissioner was also exerting pressure on him to produce as quickly and cheaply as possible plans for a host of other buildings, including a large government complex on Julian’s Way, near the King David Hotel and the YMCA, meant to hold the as yet only theoretical legislative assembly. Despite all these distractions, however, Harrison remained determined not to take sides or cut corners but to see into being his syncretic masterpiece. So it was that he closely supervised the same Italian contractors responsible for Government House, E. di A. De Farro & Co. of Alexandria, Cairo, Jerusalem, and London, who managed the large crews of Arab and Jewish workers, craftsmen, and technicians. Cork tiles, rolling shutters, electric light fixtures, door fittings, and locks would be shipped from England, along with most of the rest of the museum’s equipment—from fire extinguishers to electric clocks to display cases with adjustable bronze feet. The apparatus for the so-called Optical Lantern Room would come from Switzerland, while the terrazzo work and cement tiling would be produced by a Jewish firm in Jaffa. And again Harrison arranged with the ceramicist David Ohannessian to create several vivid pieces to punctuate the building’s otherwise muted palette. The first was an elaborate turquoise, blue, black, and cream effusion of Andalusian-styled cuerda seca ceramics that would cover the walls and ceiling of the intricately domed pavilion at one end of the cloistered central courtyard. The other was a plainer installation of small black-and-white tiles that together formed blocky Greek letters and sent a line from Plato running in a ribbon around the upper walls of the circular Archaeological Advisory boardroom like a length of antique tickertape.

Harrison chose the phrase ostensibly because it contains the first-ever use of the Greek word archaiologia, or the study of antiquity—THEY ARE VERY FOND OF HEARING ABOUT THE GENEOLOGIES OF HEROES AND MEN, SOCRATES, AND THE FOUNDATION OF CITIES IN ANCIENT TIMES AND, IN SHORT ABOUT ANTIQUITY [ARCHAEOLOGIA] IN GENERAL—though this may be one of the building’s dry inside jokes, since as Harrison of all people knew, this dialogue, Hippias Major, is not so much concerned with antiquity as it is with beauty, and the question of just what that is. A pretty girl? Gold? To be rich and respected? Or is beauty what is appropriate? That which is useful? Favorable? The pleasure that comes from seeing and hearing?

Socrates and his fellow philosopher Hippias don’t resolve the question in the course of their dialogue. But in its final words Socrates tartly tells Hippias how much he has benefited from their conversation: “For I think I know the meaning of the proverb ‘beautiful things are difficult.’” In a way, this writing, too, was on the wall.

* * *

At around the same time that the latest riots broke out, Harrison invited Eric Gill to travel to Jerusalem to carve a set of ten bas-reliefs for the museum courtyard. The idea he’d proposed to the maverick Catholic craftsman wasn’t explicitly political, but it might as well have been, sitting as it did at such stubborn odds with the aggressive nationalistic tug-of-war now playing out around him. He wanted Gill to create a set of carvings that would line the walls of the court and represent “the various civilizations which have formed the cultures of the land of Palestine.”

Although the scheme was essentially backward looking and maybe even a bit staid, there was, too, a more pressing dimension to the design. Set at even intervals between the cloisters’ columns, each relief would be placed in equal relation to the others, with no single culture dominating but all of them coexisting in the bright calm of the museum’s inner sanctum. While Harrison was far too politically reticent to ever make of his architecture an outright argument, the space he had conceived as the building’s heart does seem to express a kind of bottled-up, unspoken desire for the strife just to stop, or at least to subside temporarily as he hoped it would within the placid realm of this enclosure, with its lily-pad-dotted, goldfish-filled reflecting pool and wide-open view of the sky.

The vision of such a peaceful oasis in mind, Harrison sent Gill a list of “ancient nations” for him to consider carving, and the sculptor agreed to take on the Jerusalem assignment—which would constitute for him both a practical stonecutting job and profound religious pilgrimage, or vice versa. Different as Harrison and Gill were in so many basic respects—the former intensely private, even-tempered, monkish, deliberate, skeptical; the latter charismatic, vatic, voraciously sexual, spontaneous, devout—their dedication to the notion that “art embraces all making” bound them in an essential way, as did an unwavering, DNA-level Englishness. Gill prided himself on his vehement nonconformism and ability to shock, but he’d also rendered public sculptures for some of the stodgiest institutions of the English establishment: the Stations of the Cross at Westminster Cathedral, the reliefs of three of the four winds that face the headquarters of the London Underground, Ariel and Prospero on the front of the BBC’s Broadcasting House, and so on. One of Gill’s protégés, the poet, painter, and engraver David Jones—who would spend several weeks with him in Jerusalem while he carved at the museum and walked the actual Stations of the Cross—would describe his friend and mentor after his death as “absolutely colossally English. I don’t think I’ve ever met anybody who was so terribly English,” something that was often said of Harrison, despite all his years abroad. Consciously or not, his decision to bring Gill to Jerusalem at this particular moment in his life and the life of the country seemed almost a way of buttressing his own British sense of self and of the fundamental Britishness of even his most Palestinian buildings. Besides all the ancient nations the Palestine Archaeological Museum was meant to represent, in other words, the civilization this compound would ultimately come to stand for above all others was that of Britain and the British Mandate. It was an artifact in the making.

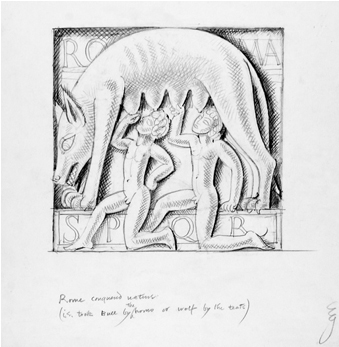

After consulting in early February 1934 with Harrison’s old friend the archaeologist George Horsfield, Gill rendered quick sketches for each of the reliefs and sent them to Harrison, together with a note in his spiky yet flowing hand: “I hope,” he wrote, “you won’t think the figures look too stumpy & clumsy & comic. You see in such small panels … it’s not possible to retain naturalistic or academic proportions.” Gill’s trademark blend of sincerity and playfulness does indeed give the blocky figures an almost cartoonish look—though the approach works well to leaven what might otherwise be a ponderous assignment. The pencil sketches come complete with scrawled picture-book-styled captions that summarize in a single phrase the contribution to Palestine of each civilization. These wouldn’t appear in the final carvings but seemed to serve as conceptual goads: “The Chaldeans brought agriculture,” “Egypt brought the rule of Kings,” “The Phoenicians came in ships,” “Israel brought the Law,” and so on, through what was brought by the Greeks (Humanism), the Persians (“Strange Rites”), Islam (the Koran), and the Crusaders (Building). The Byzantines “found the true cross,” and Rome, which “conquered nature (i.e. took Bull by the horns or wolf by the teats),” is the most childlike of all the somehow defiantly childlike images, and shows the kneeling, naked Romulus and Remus suckling hungrily from their canine wet nurse, Lupa.

“Also I hope,” Gill wrote Harrison, anticipating the response to such stylized images, “there will not be too much criticism on archaeological lines—the exact shape of the Phoenician galley or of a crusader’s helmet. I’ll go to the British Museum & the V&A this week but I’m sending these sketches without delay so that you may see what I propose.”

By late March, Gill and his assistant, Laurie Cribb, had made their way by boat then train to Jerusalem, where they met and immediately liked Harrison. “Suffice it to say that he’s a very nice man indeed & most kind and enthusiastic. (Age 42),” Gill reported in one of his brisk letters to his wife, back in England. Gill was visually alert, but he confined himself in a matter-of-fact and cheerful way to the most imprecise of physical descriptions: “Clean shaven, typical architect’s face,” whatever that might mean. As soon as they arrived at the train station they were whisked off to have a “splendid” breakfast and hot baths at Harrison’s “beautiful” house, then were driven to see the museum, deposited their tools there, installed themselves at St. Étienne’s Dominican convent outside the Damascus Gate, and—by the next day—were already hard at work.

“We’ve started the job. V. difficult to get started. It’s v. hot here already & v. glaring and dusty. But lovely beyond words—incredibly lovely.” Performing the Middle Eastern equivalent of bringing coals to Newcastle, Gill had shipped a supply of Derbyshire-quarried Hoptonwood stone all the way to stony Jerusalem, and—as though it were just another day back in his workshop in Buckinghamshire—started “roughing out” work in a small shed near the museum. Once the stones were fixed on the wall, he’d begin carving, and after a week he’d be able to report that “all is well & we are well … The work is going on but I have been delayed by having to make new designs for three of the panels (owing to criticism by local pundits).” He and Harrison had been given, he wrote in another letter, “a lot of bother” from various archaeologists about the details of the panels, “but eventually we decided, having got all we wanted out of them, to leave the archaeology behind—they said it was archaeology, the others (me & H) … said nay, it’s nought but very nearly complete nonsense.”

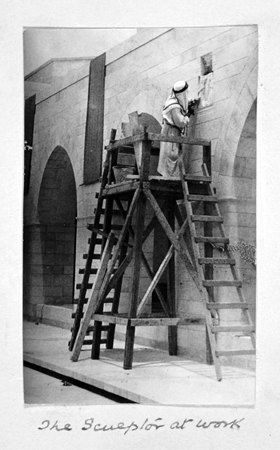

Having switched his usual stonemason’s smock and felt hat for a specially ordered gold-and-black-striped robe, along with a traditional Palestinian kaffiyeh and ‘igal to keep the sun off his neck, he was carving long, hard days, from 7:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., in the bright light on a wooden scaffold. “Up to the present,” he wrote at the end of April, now finished with five of the ten panels, “I’ve been working all on the shady side of the courtyard … But to-morrow I start on the sunny side & then I shall know what it is really like. It’s very hot here now—you can hardly pick up the chisels if you leave them in the sun.”

Once he’d completed the reliefs, Gill would also carve a tympanum over the museum’s entrance—as he put it, “a half circle representing MAN! (i.e., man from the point of view of museum curators).” Though an early sketch shows a carpenter sawing wood and a farmer threshing wheat under a tree, the carving that he’d finally render—while suffering from a severe toothache—shows two blank-faced soldiers, swords at their sides as they kneel and raise their arms in peace or surrender before a leafy tree. Meant to symbolize the meeting of AFRICA and ASIA in Palestine, they may be Assyrians, they may be Crusaders, but either way, “I am,” Gill would write Harrison afterward, “v. miserable about the main door. I was ill when I finished it. It shows.”

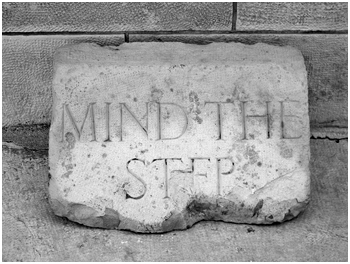

Despite his abscessed tooth and the somewhat thick symbolism of these various carvings, Gill also managed to bring a light touch to the smaller objects and multiple signs that punctuate Harrison’s building and give it—for all its Eastern monumentality—a certain gentle English whimsy. He fashioned, for instance, a toylike gargoyle that would spew water gently into the courtyard fountain and designed the clear, somehow good-natured English, Hebrew, and Arabic lettering that Cribb would cut into the stone and paint a vibrant red all around the museum:

WAY IN → SOUTH GALLERY CLOAKS

The letters on the signs, from EARLY BRONZE AGE 3000–2000 B.C. to DRINKING WATER, are all treated with the same unfussy respect, as is the warning to

placed like another ancient relic near the Roman altars and Byzantine lintels that fill the courtyard cloisters.

* * *

When they weren’t carving, Gill and Cribb spent hours with Harrison, walking and talking and taking in the Christian sites—to which Gill as a fierce believer was especially drawn. He and Harrison became quite close during this period. (Gill would later “affectionately dedicate” his Palestine Diary—a collection of letters to his wife from this journey—“to his friend Austen St B. Harrison.”) And in later years, Gill would look back rhapsodically on his time in Jerusalem and call Palestine “the last of the revelations vouchsafed to me.”

“Far … from finding disappointment in Palestine I found only good,” he’d insist, sounding a little like a plainspoken British Else Lasker-Schüler—who was as it happens visiting the city for the first time that same month, though the two Jerusalem-entranced caftan wearers never met. “For Palestine is the Holy Land … the antithesis of everything our England stands for.” On top of that, “I never saw or imagined anything more lovely than the Holy Land … so also I never saw anything less corrupted by human pride and sin”—words that sit oddly in relation to the far messier shifts between rapture and revulsion that he set down in real time. In one especially raw moment, Gill wrote his wife that it’s “impossible to convey Jerusalem to you in a letter. Its marvelous loneliness & its confusion. I am so … torn asunder between love & hatred & so worried by the job in hand and its futility … I am so sorry.” It must have been something in the chalky water: “The city is fundamentally depressing—tragic, confused, divided, surging with suppressed hatreds & conflicting cultures—the only peace the peace preserved by English policemen & why do they trouble to possess it?”

It was in many ways the question that Harrison had been asking himself with growing anxiousness of late, and even as the museum neared completion and he labored to finish as speedily as possible plans for a range of other buildings—the Jerusalem post office; the massive block of government buildings with its legislative assembly; an uncharacteristically sleek, whitewashed, almost Mendelsohnian government printing press; among others—the politics of his office, and of the country in general, weighed on him more and more.

“To have almost finished the Museum is for me to feel a great sense of relief—a great load lifted off my shoulders,” he wrote to his mother in October 1935. “It might have been something more than this had I not been working under a cloud here.” The building wouldn’t open to the public for another three years, as the exhibits and library books and laboratory equipment were moved in and unpacked. But other architects had already praised its design in the strongest terms: Frank Mears—“a man not given to enthusiasm … who knows some of the problems with which I have had to wrestle from having worked in this country”—wrote to tell Harrison that the museum was “an object lesson to all of us on the virtues of simplicity and restraint.” An article by Lotte Baerwald, widow of the German Jewish architect Alexander Baerwald, who had built several major buildings in Palestine, appeared in a Berlin Jewish newspaper that same year. Under the headline “Ein Großer Architekt: Harrison,” she declared, “Palestine may count itself happy to possess as its chief architect Harrison, a great artist. Where he has a hand, there rises a masterpiece. But,” she wrote, “who knows Harrison? Who speaks of him?”

For all of this adulation, though, he felt anything but buoyed up. “It would,” he brooded, “take a lot to turn my head: I am much too conscious of my ineptitudes and failures.” And even as he was praised in grand terms from afar, the strain at close range had intensified. “My difficulties increase so that I am beginning to wonder whether I shall be forced to get out. For if only I could weather the storm there is much interesting work still to do in Palestine. Wauchope is so hounding me,” he wrote in exhaustion to his mother, “that I feel almost that he hopes I will resign. This must sound silly to you, for he is such a big man and I am such a little one.”

That storm was, as always, political but this time it brewed in the grayest, coldest, most bureaucratic sense. While Harrison’s artistry may have been appreciated in the big wide world, back in the cramped confines of the Public Works Department there were, according to one observer, “terrible rows going on.” Jobs had been given to private architects, which was “rather a smack in the eyes for Harrison … as he is supposed to do all Government buildings, but there is stacks to do, and Harrison is an artist and a dreamer.” His friend George Horsfield even wrote to Harrison’s mother to confide his concern about Austen, who “takes life hard. The creative spirit is strong in him and he suffers accordingly.”

Politics of a more national sort also affected him directly. Not only did Wauchope seem personally unimpressed by Harrison’s designs, he had made a point of seeking out Jewish architects and giving them work. “We are,” he explained, “a Mandatory Power and I think where possible we should employ Palestinians, more especially where they can leave their mark on the land in such a way as architecture lends itself.” By Palestinian, he meant Jewish: “There are,” he wrote, “no Arab architects of proved capacity.” Although the government’s assignment of architectural commissions was hardly the cause of the Arab Revolt that exploded in April 1936, the perception of such economic and political favoritism was partly what had prompted the latest—and by far the most sustained—blast of local violence to date. (Chaim Yassky was now running his makeshift field hospital out of the old Hadassah building on the Street of the Prophets; Erich Mendelsohn was hard at work on plans for the new medical complex on Mount Scopus.)

By August 1937, Harrison had endured quite enough of the never-ending ethnic and personal agon, to say nothing of the way each new crisis affected his architectural work. “I am very, very tired—” he wrote to a friend in England that same month, “the result of two years with nothing fruitful to do. Job after job has been transferred to private architects & those left to me have been abandoned. Mendelsohn got my Haifa Hospital after I had prepared sketch plans & estimates … I am taking advantage of the obscure political situation to try & get out … I have got into such a state mentally that I can stay only at the risk of going off my head. I ought of course now to be doing my best work—I am 45. If I go I must, I suppose, give up architecture. I am thinking of living in Greece or on the Bosphorus…” He was considering, he said, “wandering” for half a year or more, “to recover my mental equilibrium. I don’t think I could live in England longer than a month.”

“You don’t,” he asked, “know a Maharajah, a sultan or other oriental potentate who wants the services for ten years or less of an architect saturated with Near Eastern traditions do you? I should make a good court architect & should be careful not to design anything so perfect that my lord should be tempted to cut off my head.” He was, it would seem, joking.

* * *

And then it was over. He had “escaped.”

He felt “like a convict escaped,” he wrote Ena, repeating and apparently savoring that word, “from some penal settlement in South America.”

After waiting exactly fifteen years and a day since he started work in Palestine—the minimum required to receive a government pension—he fled in secret, telling only a few close friends and his assistants; all the furniture and rugs in his Abu Tor house were sold off in his absence. After he left, he received letters from various admirers and acquaintances, surprised by and sorry for his departure: “Good luck in your care free future,” wrote the chief of police, a friend. “I regret that for the moment we cannot build aesthetically beautiful police stations but only grim loop-holed buildings to withstand the concentrated anger of a population driven to despair by a policy which might have been carried out with a minimum of mental and physical suffering and which even now might have been carried into happier channels.”

Back in England, Eric Gill sounded cheered by the news of his leaving: “Thank goodness you are now free. It is jolly fine I may say in a manner of speaking no longer to have to think of you languishing like a suppressed volcano at Jerusalem … You must have had some bad moments when you were packing up at Deir Abu Tor and it’s horrid to think of those rooms thus desolated—the first room I entered in Jerusalem. If it comes to that I can’t bear to think of Jerusalem & no Austen groaning in the wilderness.”

He escaped before the museum’s grand opening in January 1938—canceled at the last minute when the English archaeologist J. L. Starkey was ambushed and murdered on his way to the ceremony by what one newspaper account called “a party of Arabs in circumstances of shocking brutality.” He escaped before his Jerusalem post office was finished and feted, its counter promptly blown to bits and that British sapper killed by the Irgun and their Zionistically charged gelignite packages. He escaped well before the British Mandate limped to a close in mid-May 1948. That same week one prominent English architectural journal would publish an article complete with photographs of his plans for the government compound which, the write-up explained, became “obsolete” with the 1947 UN resolution to partition the country between Arabs and Jews. There was no longer a need for a general assembly where all the legislators could sit together. And now, even though “this partition scheme has been abandoned,… even if some central government emerges from the present chaos it is unlikely that this project will ever be realized.”

It wasn’t just the unbuilt structures whose fate was foggy. In December 1947, right after the UN approved partition and civil war erupted, the Mandatory authorities would move the Jewish employees of the Palestine Archaeological Museum, together with a card index of objects and various files and books, across town to a temporary branch office in Mendelsohn’s Schocken Library. The British curator, Arab employees, and most of the museum’s holdings would stay behind, though by November of the next year, on a stopover in London between trips to Cyprus and Egypt, as war in the new state of Israel raged, Harrison would write to a close Jewish friend back in Jerusalem that “I am expecting to hear anyday that the Palestine Archaeological building—the only building I have designed for which I have some respect—has been blown sky high. It presents a sorry appearance. I believe it is occupied by some of Abdullah’s men.”

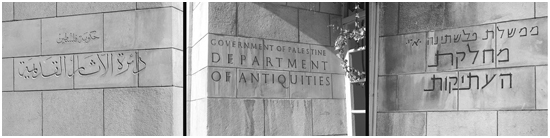

In fact the building would continue to stand, largely unscathed, remaining under the control of an international board until 1966, when Jordan’s King Hussein briefly nationalized it. After 1967 and Israel’s occupation of East Jerusalem, the Israeli Department of Antiquities and many blue-and-white flags would be installed there. The new administration would peel back the sticky tape that hid Gill’s Hebrew letters for a period after 1948 and repaint them the same old red … though the Arabic inscription indicating

would remain pointedly colorless. The building would soon be absorbed into the Israel Museum and come to be known as “the Rockefeller”; the department itself would later evolve into the so-called Israel Antiquities Authority.

For all the disgust he evinced at his departure, Harrison would in fact slip back for a few brief visits, before 1948 and after it, to the city’s Jordanian side. In the mid-1940s he even designed a compound for the British Council in Jerusalem, as well as a warden’s lodge for the Ophthalmic Hospital of the Order of St. John—the plans for both of which were eventually scrapped. (“I am,” he wrote a friend from Cairo in late 1946, “extremely busy planning buildings which will never be constructed.”) But with the years, he tried to distance himself from the place and to obliterate in uncharacteristically extreme fashion the traces of his time in the city; he burned most of his personal papers and preserved just a weathered sheaf of retyped and, it seems, redacted correspondence. For whatever reasons—professional, political, sexual?—his last two years in the country would completely disappear from his private written record. But he couldn’t erase the lingering fact of his presence in Jerusalem.

He’s there on a hot July day well into the next century, for instance, when I weave my way through the teeming streets of East Jerusalem and pass through a metal detector and under the hard gaze of several Russian-accented, pistol-packing Israeli security guards. They’re especially suspicious of those (very few) who arrive on foot at the gate of this fortresslike Israeli institution in the middle of a busy Palestinian neighborhood. But no matter which government claims control of this highly sensitive piece of property, it’s still somehow Harrison’s museum.

Or so I tell myself as I move around the smoothly curved wall of the barbican, now a kosher cafeteria, thread around the employees’ crookedly parked cars, up the steps, and through the cool and cooling entrance, under Gill’s kneeling soldiers and their truce-inducing tree. No matter its besieged-seeming current state, this remains one of my favorite buildings in the whole city—an island of calm and focus—and after I make my way through the empty and echoing tower hall and down a long, vaulted corridor, I enter a room to one side. There, I open a cardboard box filled with sketch pads, postcards, press clippings, telegrams, and gardening notebooks, and pull out that fading typescript with its handwritten title, “Some Letters of Mine,” the “some” a wry provocation to the would-be biographer.

These are the letters he spared from the fire—those that, for all his strictly guarded privacy, he wanted someone, or ones, to read: a papery time capsule. After wandering with him from Egypt to Cyprus to the Greek island of Evia and to Athens, where he lived for years, died at age eighty-six, and was buried, they’ve made their unlikely way back to Jerusalem and to this space of his own design, the former British Record Room, the onetime Jordanian Scrollery, the present-day Israel Antiquities Authority Archive, which will soon serve some other purpose altogether, as yet unspecified.

In a few years, this archive, and with it Austen Harrison’s written traces, will also be moved—into a sprawling new archaeological campus designed by Moshe Safdie, the most renowned and would-be Herodian of contemporary Israeli architects. If Harrison, “the” architect of the British Mandate, favored modesty, proportion, and understatement, Safdie, “the” architect of post-1967 Israel, has no such preferences. His ostentatious plan for the campus—which will sit near the Knesset and Prime Minister’s Office and, it is said, hold two million relics, fifteen thousand pieces of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the largest archaeological library in the whole Middle East—features a massive concave glass-and-polymer fabric canopy, held aloft by soaring tensile cables and modeled in the most literal fashion on the tents used on local archaeological digs. Aggressively symbolic in more than that sense, it also seems meant to invoke an engorged variation on the biblical tabernacle, and so to demonstrate the Jewish state’s God-given rights to both the ancient relics belowground and the country’s built future.

But all that is yet to come. Contemplating the layers of what the older museum’s builder has left behind, I can only dig, and keep digging, here and now.