Erich Mendelsohn wore thick glasses and had only one, weak eye—cancer forced the removal of the other when he was a young architect in Berlin, and total blindness had since been a hovering threat—but from the moment he set foot in Palestine he couldn’t stop denouncing his fellow Jews for their failure to see.

The myopia he encountered there pained him. (So his wife, Luise, would write, years after his death.) He was ashamed by the ugliness of the Jewish settlements, the boxy apartment buildings, the slablike synagogues that had sprung up haphazardly throughout the land. The absence of planning also galled. Without any apparent forethought, cities had erupted, he said, like so much “wild, tropical vegetation.” Even the poorest Arab villages were by comparison models of harmonious design—their dirt roads and low houses arrayed according to the shapes of the hills, each of them circling skyward toward a spiral-like crown. Luise would later report that throughout their years in Palestine he’d often stop the car by the side of the road and hop out, eager to study the lines of a favorite village on the old carriageway to Jerusalem. “A little heap of turned-up sand and rocks,” it gave “the impression that it was lifted up out of the earth,” and its elemental appearance fascinated him.

Meanwhile, just a short drive away, all those well-trained European architects who gathered in Tel Aviv cafés to argue and smoke as they vied for commissions and held competitions were still carrying on as though they were in Vienna, Hamburg, or Dessau—as though history and Hitler hadn’t happened, as though it were possible to keep plunking down glass houses on every other corner and ignoring the climatic and cultural facts of where they’d landed: in a hot, ancient, blindingly bright, Middle Eastern land.

Astigmatism had not, he insisted, always been so rampant among his people. The ghetto was to blame. Over centuries of “pariah existence,” he said, “their eyes had forgotten how to distinguish between good and bad. A ‘better’ building meant to them cement instead of wood, and ‘more beautiful’ meant complicated instead of simple. They had, therefore, to be trained anew to see.”

To make his point more forcefully, he’d sometimes flourish an ancient ceramic vessel that he claimed demonstrated the creativity and craftsmanship that long ago characterized the Jewish people. Known as a “tear jug,” this was a pitcher meant to hold the weepy runoff of its chronically saddened Semitic owners.

Mendelsohn had little patience with Jews who sniffled. He himself was less tearful than he was appalled by the “brutal disregard” of the country’s singular beauty and by what he saw as the refusal of these transplanted architects to recognize that circumstances had changed, the world had changed, their materials had changed. And furthermore, “Palestine is not a virgin country insofar as architectural tradition is concerned.” Though they seemed to believe they were starting from scratch, the recent arrivals had much to learn from the local Arabs who’d come to understand over centuries how best to shelter themselves from the glare, how to build with thick, cooling walls and small, carefully placed windows. It shocked him especially to see scattered along the streets of the country’s raggedy Eastern cities crass imitations of his own sleek German designs—“bastard buildings,” he called them, in which the steel and reinforced concrete that he’d used so dynamically in his earlier European work had been yanked out of context, used carelessly, hurriedly, on the cheap, and all in the name of settling the hordes of immigrants who—like many of the architects themselves—had just stumbled blearily onto these Mediterranean shores. With their extravagant use of glass, these buildings were, he fumed, “wholly unsuitable to the sub-tropical climate of Palestine.” Such construction had “almost degenerated into a pestilence.”

Erich Mendelsohn hadn’t come here to make friends.

* * *

Decades later, as a widow, Luise would explain that many viewed her husband as “arrogant, impatient, contemptuous, sarcastic” but that those who knew him well and whom he trusted saw him as unstintingly generous, endlessly attentive, and, what’s more, “humble … in the profoundest sense of a deeply religious personality—always aware of the great unknown.”

But he couldn’t help himself and his prophetic rages, especially once he reached Jerusalem. And then it wasn’t simply scorn that he let rip in this oracular manner but a piercing, almost painful, ambivalence that came blasting out, as though the violent confusion of sensations he was experiencing there hurt him physically.

Taking in all he saw from the heights of Mount Scopus, for instance, the squat man with the soaring ideas was flooded by waves of mixed emotion. The colors in the distance were at once jumbled and overwhelming, with the violet-blue Judean hills stretching as far as the Dead Sea, and the Old City walls that seemed to him gray-green, covered in a glorious ancient patina. The site was (he would write Luise in excited exhaustion that night) “indescribably beautiful—yes, shattering—

“—but the present buildings are scattered about without any plan, in a terrifyingly small-minded way.”

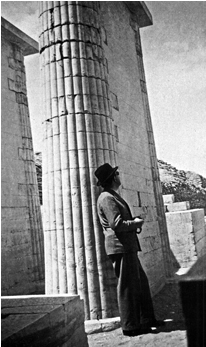

He, meanwhile, had a definite plan, or plans—for this summit, for this city, for this country as a whole. And also for himself. That was why the great Erich Mendelsohn was here, after all, traipsing around the rocky wastes of this historic hill on a blustery December day in 1934, swiveling his head and its fedora this way and that as he took in the boggling view.

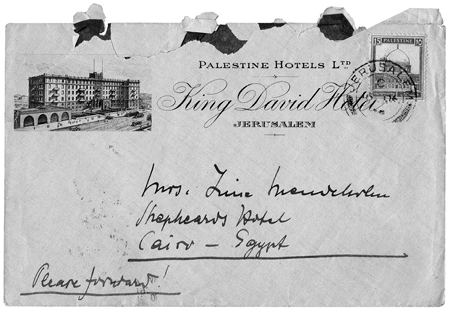

Often, Mendelsohn would simply drink in a landscape or a cluster of buildings for its own sake. Just as that village on the way to Jerusalem always made him slam on the brakes and spring from the car, go scurrying out with his sketchbook and single squinting eye, whenever and wherever he was hired to build he’d apply the same thirsty observational method. But today was an official visit, not a spontaneous pit stop with his pretty wife or a solitary surveying session. Hearing of the presence in town of the well-known refugee architect—currently working in London, though for a few weeks now he’d been running a makeshift drafting office out of his room in the swank, newly built King David Hotel—the Kishinev-born, Odessa-trained director of the Hadassah Medical Organization, Chaim Yassky, had invited Mendelsohn to accompany him up the mountain.

Yassky was an eye doctor, of all things, the perfect companion for Mendelsohn as he set out on his quest to correct the Jewish people’s collectively impaired vision. And although he didn’t yet have the approval of his bickering building committee to hire Mendelsohn (they preferred to hold a competition), the doctor also had plans. The old Rothschild-Hadassah hospital in the heart of town on the Street of the Prophets was too small, crowded, and run-down to serve the city’s rapidly expanding population. At the start of the nineteenth century, Jerusalem was home to just eight thousand, all living inside the walls; by late 1917, when the British occupied Palestine, the number of residents both within and without those medieval ramparts had swollen to fifty-four thousand. Now—seventeen years since the start of English rule and the approval of the document known as the Balfour Declaration, which pledged that His Majesty’s government would use its “best endeavours” to facilitate “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”—the city’s populace stood near a hundred thousand and would, Yassky knew, continue to grow. With such figures and the pressing physical facts they suggested in mind, he wanted Mendelsohn to examine the more remote Mount Scopus site to the northeast of downtown and consider the prospect of designing a modern hospital and medical school on the saddle of the hill. There it would rest between those few scattered buildings of the fledgling Hebrew University and the pristine British War Cemetery, with its regiments of cross-bearing headstones standing since the Great War at perpetual attention.

The plot Yassky had selected was, as it happens, the perfect limbo-like spot on which to build in the timeless manner to which Mendelsohn aspired—poised between the promise of what would be (the new university and all it represented for the Jewish people) and what had been (that “great” war and its more universal, and devastating, meaning). The hospital’s cornerstone had been laid just a few months before, and the proceedings of the ceremony broadcast by live wireless—a first—from these windy heights to the whole wide world, or at least to Cairo, London, New York, and the Wardman Park Hotel ballroom in Washington, D.C., where the fifteen hundred white-gloved delegates of the Hadassah Women’s Convention assembled to hear the staticky speeches beneath a banner that proclaimed WE WILL BUILD.

As gangly and calm as Mendelsohn was soft hipped and excitable, Yassky had made his way in the world as a sober man of science, but he knew a thing or two about the sweeping rhetoric of sanctification and striving that was, at this moment, so popular in Palestine. Using the loftiest terms, he had managed to convince his endlessly wrangling committee members of the need to situate the country’s new, state-of-the-art teaching hospital in the “cosmopolitan city of Jerusalem”—not homogenous Tel Aviv—where it would both serve all the citizens of the country, regardless of creed, and “foster … the progress, if not the salvation of the Jewish community of Jerusalem, which will eventually become the spiritual center of Jewish Palestine.”

Such talk appealed to Mendelsohn, whose own visions, like his ambition and his scathing opinions, were hard to contain. The hospital constituted just one piece of his grand design for this Jerusalem ridge. He’d also already begun to imagine what he called “an entirely new master plan for the whole University complex”—not just a building or two but a complete network of carefully arrayed structures and roads, which would come together as a focused unity and flow naturally across the hilltop “like a proper organism.” (As he conjured the image of this marvelously concentrated campus to be “executed by one hand,” his own, he may also have been picturing himself strolling across its landscaped grounds, which he meant to plot personally, olive tree by olive tree; there were rumors around town that a chair of architecture at the university would be created especially for him—rumors he did nothing to dispel.) And the university was really but a single element of his gestational plan for all of Jerusalem, and for the building of Palestine as a whole. Mendelsohn wasn’t alone, of course, in drawing the essential link between these different realms. Its founders hoped that the university on the hill would, when it was built, represent nothing short of a new Temple, a “House of Life,” which would aid “in the quest of modern Judaism for a recovery of its soul.”

* * *

No one would ever have accused Erich Mendelsohn of excess modesty, but the idea that he should be the one to give architectural coherence to this campus, this city, this land wasn’t some megalomaniacal fantasy of his own. Among Weimar Germany’s most acclaimed architects, Mendelsohn had run one of the largest and busiest practices in that country until his hasty departure just the year before. He’d long been praised, if also scorned, for his boldly expressive and trailblazing designs, almost all of them rendered for Jewish clients. One of his earliest buildings was still his most famous—the singularly sculptural Einstein Tower, a modernist spaceship of a stucco-clad observatory and astrophysics lab created around 1920 in Potsdam, so that its soon to be Nobel-winning namesake could test the theory of relativity there. More subtle and suggestive of his work to come were the renovated offices of Rudolf Mosse, a major Berlin publishing house. That building’s radically rounded, almost vehicular, corner façade caused a sensation when it was unveiled in 1923—on that city’s very own Jerusalemstrasse.

“The primary element is function,” he wrote breathlessly to Luise that same year, speaking of architecture in general. “But function without a sensual component remains construction.”

Although he claimed inspiration from the structural logic of nature and always kept a collection of seashells and petrified wood on his worktable, he had a gut feel for the energy and rhythmic vitality of the booming twentieth-century city. On a 1924 voyage to New York, Chicago, Detroit, and other more rural American spaces, he found himself at once allured and appalled as he snapped vertiginously neck-craning pictures of towering skyscrapers, neon-flashing billboards, and looming elevated tracks. Improbable as it sounds, on the SS Deutschland sailing to the States, he’d befriended fellow passenger Fritz Lang, then plotting his own Metropolis. As Mendelsohn wrote in Amerika, the book of photographs and aphorisms that documented his travels and included several images shot by Lang—who seems to have learned a few architectural things from his shipmate and applied them to his movie—he saw in the United States “everything. The worst strata of Europe, abortions of civilization, but also hopes for a new world.”

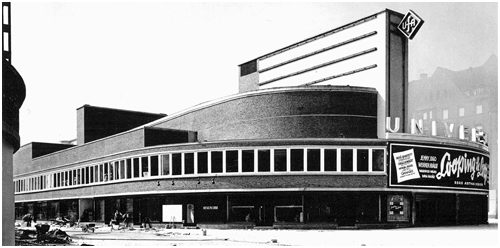

It wasn’t just the company he kept on the deck of the Deutschland. There was something essentially cinematic about Mendelsohn’s own vision of the restless drive and flux that ruled the teeming streets. Sometimes this took literal form. Soon after his return from the United States, he designed a notoriously kinetic, bow-shaped movie theater, the Universum, as part of his plan for a spacious Berlin shopping, residential, and entertainment complex. Complete with a hotel and cabaret, it was the largest project built in that city during the entire Weimar period, and it held all the charge and force of his American photographs, though it converted the dizzying upward rush he must have felt in the presence of the steep skyscrapers into the sweep of a tremendous, forward-hurtling horizontal. “Motion is life!” he’d proclaimed at the cinema’s gala opening in 1928: “Real life is authentic, simple and true. Hence, no posing, no sob stories. Neither in films … nor in architecture … No rococo palace for Buster Keaton, no wedding cake in plaster for Potemkin.”

He was best known for his department stores. In his daring designs for the Herpich family’s Berlin fur emporium, for instance, and in a series of audacious structures planned for the retail tycoon, cultural patron, bibliophile, and publisher Salman Schocken, curving windows and vivid signage became the most animate of immobile elements. First sketched by Mendelsohn in the middle of a Bach concert, the Schocken store in Stuttgart was, in particular, a masterpiece of stasis and fluidity played off one another in spectacular counterpoint—a steel, glass, and travertine ocean liner always gliding down the same busy street.

While it might not have been dazzling department stores, let alone fancy fur outlets, that dusty Palestine needed just yet, various Zionist leaders had singled out Mendelsohn for the highest praise and suggested that the country should be planned by “great artists” like him. He had, in fact, come here now to design a house in Rehovot for the charismatic chemist and de facto political leader of world Jewry Chaim Weizmann and his fastidious wife, Vera. Excising himself and his business affairs from Germany, Mendelsohn’s former employer Salman Schocken was also newly arrived in Palestine, and had just commissioned a villa and private library in Jerusalem. As chairman of the Hebrew University’s executive committee, Schocken made clear as well his determination to have Mendelsohn plan the campus of the most important Jewish institution of higher learning in the land. Yassky too considered Mendelsohn “one of the outstanding living Jewish architects” and patiently defended him against the skepticism and even hostility of some of the sniffier members of the Hadassah building committee, who complained that he didn’t understand the local conditions and bristled at his “ultra-modern style of architecture,” which they deemed “not suitable for Palestine.”

Yassky remained firm, however, vouching for both Mendelsohn’s character and his talents. The doctor was certain that he would build in a manner appropriate to the context. Though he admitted that Mendelsohn was known as “not an easy man to work with” (Schocken had warned him), Yassky was intent on overseeing the construction of a unique building on this Jerusalem hilltop, a noble structure of the sort that Mendelsohn would surely plan—unlike various candidates whom he described as “capable architects, but … not above the average.” He would hate, Yassky said, “to put up on Scopus another box in Tel Aviv style,” an argument that seemed to stir something in the group as a whole. “This is not,” agreed one formidable female member of the committee, “to be an ordinary hospital but the hospital of the Jewish people.”

And it wasn’t just the design of the hospital that would be entrusted to Mendelsohn. The very week of his scouting expedition with Yassky on Mount Scopus, he had lunch alone with Palestine’s artistically inclined high commissioner, Arthur Wauchope, a friend, who promised to do what he could to put the university planning in the architect’s hands as well. (Wauchope couldn’t guarantee it, but he was in an excellent position to apply pressure to those making such decisions; the first high commissioner had been appointed by the British king in 1920, and since the official start of the Mandate in 1922, the man who held this post had commanded almost unchecked power as the ruler of Palestine.) A few days later, Mendelsohn found himself in a lively conversation with Wauchope’s young male secretary, who enthused that he “must come here” so he “could have and do everything.”

All of that said, it seemed the person Erich Mendelsohn most needed to convince that he and his practice belonged here in Jerusalem was—Erich Mendelsohn.

* * *

He regularly proclaimed his love of the land of Israel—“I … call myself its true child”—but the thought of actually coming to live and build there had remained a fuzzy and even fraught prospect. As early as 1920, he’d put his name on a Jewish Agency list of “engineers willing to go to Palestine.” And he’d tried his architectural luck there before—both working on a plan for the country’s first electrical power station in Haifa in 1923, and obsessing over designs for a business center and a tidy garden city in that same town. None of these projects took hold. Various explanations were given for this dead end, though it may well have been that his streamlined modern conceptions proved—then, as later—too much of a challenge to somewhat staid local sensibilities. According to Mendelsohn, the British high commissioner of the time declared his scheme for the power station “too European.” (Ironically, the architect noted that a Berlin villa he’d constructed during this same period was deemed by a shocked German general “too Oriental.”) It may, on the other hand, have been a clash of personalities between the difficult Mendelsohn and his difficult patron that halted that particular collaboration. The power station that was eventually erected was every bit as “European” as Mendelsohn’s would have been; based on his initial design, it is generally considered the first “modern” structure in Palestine.

Whether or not any actual buildings resulted from Mendelsohn’s initial flirtation with the country, something had shifted within him in the course of that close brush. When he’d made his first trip there that same year, the landscape had grabbed hold of his imagination. Within days of arriving, he’d sketched on a postcard a narrow Jerusalem alleyway that seemed to surge like rushing water, then swell upward toward the minaret and dome at its end—as if he were being pulled by a strong current into the view. Below the quickly rendered ink perspective, he gushed in scrawled German to an art historian friend that the experience of being there was overwhelming—far beyond his expectations—though it would “take time to settle.” Once that had happened it would, as he put it, in unapologetic shades of purple, “only fortify what has long been strong. Blood and space; race and three dimensions!”

He’d paid lip service to Zionism since his student days, but the encounter with the physical fact of Palestine now seized him in the most visceral way. He spoke of being moved by two “cycles of emotion.” One he called “oriental-atavistic,” the other “occidental-present (of today).” They both operated within him, he insisted, the tension between them urging him on. And even at that early date, this sense of being propelled by forces at once Eastern and Western, ancient and present, made him reconsider his place in the world: “No Jew able to understand his emotions,” he declared, again in rather torrid terms, “tours Palestine without the tragic touch of his own past and without the humble hope of its rebirth.”

Luise accompanied her husband on the 1923 voyage and would admit, decades later, that she, too, had been “entirely unprepared” for the effect the country would have on her. In fact, her strong attraction to the East and its people—both Jews and Arabs—“almost frightened” her. An elegant, pampered European cellist, she believed herself to be of Sephardi descent but said she hadn’t been conscious of being Jewish as a girl. She’d grown up spending summers in the Black Forest and surrounded by marble fireplaces, crystal chandeliers, and portraits of her female ancestors in silk dresses with low-cut necklines. Now this “sudden awareness of a certain belonging” was “something I could not accept easily, as it seemed to me a racial belonging.” The Mendelsohns considered themselves cosmopolitans—citizens of the world—and this tribal pull appears to have at once excited and unsettled them.

But even after they’d returned to Berlin, Mendelsohn couldn’t shake his newly urgent sense of his bond—as Jew and builder—with Palestine. Writing to his school friend and fellow architect Richard Kauffmann, already settled in Jerusalem and firmly established as one of the Zionist establishment’s favorite planners, he explained, “Although I see my work here”—in Germany—“acknowledged, needed and appreciated by the most important people, it is without the true soil desired by my blood and my nature…” Mendelsohn described his wish to “come finally to the Land of Israel,” though only if he could be assured commissions and good relations with Kauffmann and his circle. “Everything else,” Mendelsohn put it bluntly, “would then be a logical consequence of my own work.” Was this a promise or a threat? “If these conditions are met, I would immediately leave for Palestine and would inform you before my arrival.”

Like the power station, the business center, and the garden city, these plans remained on paper, folded and tucked inside drawers. And though Mendelsohn continued to toy with the idea of emigration from Germany—“Reflections kept to myself,” he wrote Luise in 1925, “on America—Europe—Palestine”—there was some nagging thing holding him back, stopping him from taking the plunge toward the East. What was that thing? What nagged?

* * *

As it was, throughout the 1920s, he had the luxury of steady, high-profile work throughout Europe and of international celebrity. He had no pressing need to look elsewhere. In fact, beginning in 1928, he’d even gone so far as to build and furnish a quietly spectacular waterfront villa in a leafy Berlin suburb as an elaborate gift for Luise.

When Am Rupenhorn was completed in the summer of 1930, its state-of-the-art music room, carefully landscaped gardens, retracting glass walls, self-regulating oil furnace, gymnasium, wine cellar, and special built-in wireless cupboards had made the couple both the glamorous toast and grumbled-about envy of Berlin society. This was a phenomenon the architect seems actively to have exacerbated by overseeing the publication of a photo-filled, trilingual book that showed off to the world Am Rupenhorn—complete with Luise’s manicure kit, the miniature fold-top desk where their daughter, Esther, did her homework, and a designer umbrella stand. In an essay published there, Le Corbusier’s Puristic sidekick Amédée Ozenfant praised and defended the “little ‘palace’” in effusive terms, explaining that “what I am particularly anxious to make clear, and what so amazes me, is that functionalism and beauty abide here, as it were, in mutual independence.” From his experience of being and working in the house, and enjoying not just its immaculate proportions but also its many subtly deployed technological innovations, Ozenfant could state, somewhat dumbstruck, that “it was as if ten mechanical guardian angels were making life easier for me.” He didn’t cite Le Corbusier’s famous formulation of the ideal modern house as “a machine for living in,” but he implied it. Am Rupenhorn was, he pronounced, “a house for a Goethe of 1930.” Perhaps not surprisingly, some considered the whole display (building and book alike) unseemly, a product of the most decadent and preening sort of self-indulgence.

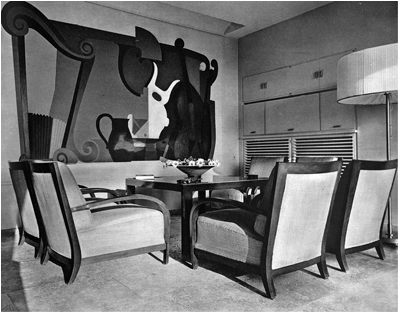

Whether or not it lived up to all the flamboyant flattery—or scathing criticism—heaped upon it, Am Rupenhorn was certainly a stylish birdcage for the cultural who’s who of that time and place. Under specially commissioned murals by Ozenfant, a Max Pechstein portrait of the striking young Luise in a dark tilted hat, and various paintings and copper reliefs by other popular avant-garde artists of the period, including Lyonel Feininger and Ewald Mataré, the Mendelsohns regularly threw lavish dinner parties and musical evenings, attended by writers and ambassadors, publishers and princes; in the afternoons, Luise would serve mocha and petits fours from a tea cart designed by Bauhaus builder Marcel Breuer. Their neighbor along Lake Havel, Albert Einstein, often arrived at their backyard in a sailboat, his violin tucked under one arm so that he could play trios with Luise and the acclaimed Hungarian concert pianist Lili Kraus. (During such spontaneous recitals, Erich would listen closely to the music at first and then, according to Luise, tune out and start sketching.)

But the walls of their opulent home—and of their troubled homeland—were gradually closing in. Having planned Am Rupenhorn down to its last monogrammed table napkin, Mendelsohn had begun to feel uneasy about the extravagance of the house and all it represented. He sensed that alternatives might lie in some simpler existence, to the south, to the east, and in the realm of that “oriental-atavistic” impulse he felt welling up within him. After a revelatory 1931 voyage to Athens, he eagerly took other trips to Italy and the Côte d’Azure, and marveled at the light, the water, the trees, the sky, and the “little rectangles, of clay or brick, whitewashed” that spilled down slopes and huddled in valleys throughout the region. His ecstatic descriptions of these landscapes sound like verbal watercolors, painted in a kind of sun-struck daze: “Heavens, water, the distant islands and reflected light sink into the blue, into this play of blue upon blue in eternal ease.” The Mediterranean lured him with “its fullness, its tranquility,” and he mused about how “the Mediterranean contemplates and creates, the North rouses itself and works. The Mediterranean lives, the North defends itself.”

The contrast between the “eternal creative force” he felt coursing through these warm, bright climes and the chill of present-day Germany could not have been starker. Ironically enough, in these very years a famously nasty, racially charged architectural controversy had erupted when a high-profile development of boxy, state-of-the-art buildings, curated as a permanent exhibit by Mies van der Rohe in Stuttgart, was attacked by German nationalists for looking like “an Arab village” or, in fact, “a suburb of Jerusalem.” The lack of properly pitched German roofs typified for the Weissenhof’s critics the “rootless” nature of its creators—a kind of modernist all-star team, featuring Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, pioneering Dutch architect J.J.P. Oud, leading German builders Peter Behrens, Bruno and Max Taut, Hans Scharoun, and nine other talented Europeans, including Mies himself. Distinguished as this crew was, they were damned as “nomads of the metropolis,” who “are not at all acquainted with the idea of the parental, let alone the ancestral home.” Their flat roofs, it was hissed, “no longer keep us under German skies and on German soil, but displace us to the edge of the desert or into an oriental setting.” A notorious Nazi postcard added camels and swarthy turbaned “natives” to the actually Swabian view.

While almost none of the Weissenhof architects were Jewish, the taint of “degeneracy” seemed to be catching, or leaking in through those despised flat roofs. Mendelsohn himself didn’t submit a design for the Stuttgart project. (Though invited and involved, in the end he chose not to participate.) It’s reasonable to think, however, that the generalized anti-Semitic animus the exhibit stirred up was a goad to him—a perverse sort of inspiration—as he contemplated his relationship to the East and the possibilities it presented for building. It’s also clear he’d long understood that something was seriously rotten in Deutschland. On his return from an especially euphoric journey to Corsica, he declared to Luise that “three days in Berlin have again revealed the oppressive burden of this country condemned to fall to pieces, of this city with its false pretensions, its forced sense of merriment, and its entirely groundless hopes.” All the plans and ventures being undertaken around him were, he warned, “the convulsions of feverish, sick people, who fight against their illness without knowing whether they’ll suffer further, more severe attacks.” He spoke of an “emptiness that cannot be filled. I feel it in my office, whose existence lacks any foundation, and in our house, whose solid existence constricts and oppresses me.” Not that this sense of strangulation made the way forward clear. Even after Mendelsohn had announced to his wife the need to “free myself, which is to say us, from this place,” he’d continued to muse about various options, zigzagging in a single breath between the possibilities of Palestine and (remarkably) Lake Como or “who knows where?”

But the situation in Germany gradually became intolerable—and by 1933, the threat had arrived at their front door. Luise rose from bed on a gentle Berlin spring morning to the sight of a swastika-emblazoned flag moving up and down their street and the sound of schoolchildren singing “Germany awake, awake, awake; let Jewry rot, rot, rot.” Soon after, one of Erich’s closest companions and most trusted architectural assistants arrived late to a Bach-themed party for Mendelsohn. (The architect and his favorite composer shared a birthday, and every year he and Luise celebrated the day with friends and fugues.) Glowing with excitement, the man announced that he’d been delayed because he’d just been to see the führer in person. This friend’s fascination with Hitler, Luise would later write, came as a “shattering blow” and hastened their decision to leave the country—Bach’s country.

Yet when they did flee, days later, at the end of March that year—on a night train, with just a few suitcases and a treasured stamp collection—they still did not point themselves immediately in the direction of Jerusalem.

Instead they wended their way first to Holland, then almost to the south of France where, together with the Dutch architect Hendricus Theodorus Wijdeveld and Ozenfant, Mendelsohn had laid the foundations for an ambitious “European Mediterranean Academy,” which might—had it ever materialized—have emerged as a kind of Bauhaus on the Riviera. Its faculty were to be the founders, along with a group of accomplished international artists including the composer Paul Hindemith, the Grozny-born designer Serge Chermayeff, and the eccentrically brilliant British typographer and stonecutter Eric Gill; its advisory committee counted among its illustrious members Einstein, Frank Lloyd Wright, Paul Valéry, Max Reinhardt, and Igor Stravinsky, and its course of study entailed both intensive hands-on work and more theoretical investigation. As Mendelsohn’s section of the academy’s brochure promised, the curriculum was designed to make the “young architect into a complete builder” by “unifying tradition and the desire for the expression of our own time,” with an eye toward “the formation of the future.”

But the future was more easily plotted in a theoretical syllabus than in the practical tangle of real life. With the uncertainty of the political situation throughout the Continent casting shadows, and tensions among the academy’s founders mounting, the Mendelsohns moved on abruptly to London.

Though the architectural climate in England was far more conservative than in Germany, and his passionately iconoclastic aesthetic was generally considered distasteful by the purse-lipped British cultural establishment, Erich had been embraced by a group of the more forward-thinking local architects when he’d gone there to raise funds for the academy. They helped arrange for him to live and work in London, and at a sort of coming-out party at the Liverpool Architectural Society, in November 1933, he gave a lecture on his work, and “the famous German architect” was, according to a gushing story in The Manchester Guardian, “interrupted warmly and frequently by cheers.” On this occasion, one of his hosts, the architect C. H. Reilly, announced to the assembled well-wishers that Mendelsohn would now practice in England. This declaration was met by great applause in public, though privately it gave way to real worry for Mendelsohn, as the decision to settle in Britain meant forgoing any hope of holding on to even a part of his substantial German savings. It also entailed the adjustment—or attempted adjustment—not just to the English language but to the imperial system of measurement, no small thing for a forty-six-year-old architectural maverick used to controlling every situation in which he found himself. (In his Berlin office he’d kept careful track of how many pencils were used; he also designed all his wife’s evening gowns and insisted on accompanying her to fittings at her dressmaker’s.) Although in British company he tried to blend in and now sometimes went by the Anglicized “Eric” instead of the Germanic “Erich,” English tastes and manners were hard for him to fathom, and came gradually to depress him. As he’d write to an American friend, the critic Lewis Mumford, “I do not feel very happy in England. I cannot breathe in a country without spiritual tension. I cannot work where creative fight is taken as an attack against the ‘common sense.’” For bureaucratic reasons, he was—as an alien—forced to enter into a partnership with Chermayeff, a British national. The younger, less experienced designer was himself sympathetic, though the collaboration grated badly against Mendelsohn’s self-declared penchant for autocracy.

Yet even when faced with this difficulty and discomfort, he still hadn’t picked up and taken himself, his wife, and his practice to the place that struck so many of his European Jewish contemporaries as the most obvious destination. As he tried to explain to a committed Zionist friend, Kurt Blumenfeld, who had questioned his chaotic and ideologically dubious itinerary, “Why not directly to Palestine? Here you touch a tender spot. All those years I envisioned Palestine built up by my hand, the entirety of its architecture brought into a unified form through my activity, its intellectual structure ordered by my organizational ability and striving toward a goal.” But for all his talk of blood and space, race and their somehow cosmic link to his vocation, “Palestine did not call me.” It seems he needed to be courted.

* * *

By now, however, this rainy winter of 1934, a new strain of vulnerability—or was that possibility?—had crept into his tone. Having returned to Jerusalem under changed circumstances, he seemed willing to give the place a second chance.

It wasn’t just that other doors had been summarily slammed in his Jewish face. Suddenly he was being offered these large local commissions by powerful people like Weizmann, Schocken, and maybe Yassky and the major institution he represented, to say nothing of the university of the Jewish people—and these jobs implied more jobs, which implied (Mendelsohn hoped) the realization, at long last, of that older dream of himself as Palestine’s master builder, its trusted master planner. “The hotel is filling up,” he scribbled to Luise, on a sheet of cream-and-blue King David stationery, “and work is bearing down on me. Here, I feel like one of the most important people in the land. But,” he admitted, “without any outward signs of that importance.” He almost sounded relieved—as though after all the heady, even drunken, success of the previous decade he’d suddenly sobered up.

His vision freshly focused, he seemed eager to get down to business and to reckoning with the simple thrill of the plain white page. “I am completely absorbed. I scarcely breathe, eat little.” When he stole time to sleep, he slumbered “under buildings that are heaping up.” He declared himself “wholly preoccupied.” And the generic notion of high-profile employment wasn’t what was driving him. The place itself had him in its grip. While plans for the Mediterranean Academy had fizzled, his renewed contact with the light and the air, the stone and the sand of these southern landscapes had rekindled his romantic conviction that Palestinian blood somehow flowed through his veins. “The Mediterranean,” he’d mused just the previous year, “is a first step toward a return to that country, to that final stage where we both belong.”

Belonging, of course, was directly linked in his mind to not belonging. Only a few months before, in October 1933, Mendelsohn had received a letter from the professional association of German architects, conveying “collegial greetings” along with official notification that, from then on, all its affiliates must be of Aryan descent. His membership was hereby terminated.

Meanwhile, even should-have-been allies and ostensible friends from his former life had turned their backs on him. Around the same time that chilling notice arrived in his Oxford Street mailbox, Walter Gropius, also living as an émigré in London, declared himself “no special friend of the Jew” and whisperingly denounced Mendelsohn to the organizers of a British exhibit on German building as “unpatriotic” and not “a pure German architect.” So, too, when in February 1932 New York City’s newly opened Museum of Modern Art unveiled its era-defining architectural exhibit on the International Style, Mendelsohn and his buildings were relegated to an extremely minor role, little more than bit players in a drama starring Gropius, Mies, Le Corbusier, Oud, and their rigidly unadorned glass, steel, and concrete cubes. In the introduction to the soon to be classic book written to accompany the exhibit, Mendelsohn was described by the museum’s director, Alfred H. Barr Jr., as the man responsible for “the bizarre Expressionist Einstein Tower” and “a ponderous department store.”

One of that book’s authors, a self-assured recent Harvard graduate and architectural enthusiast named Philip Johnson, had visited Germany in 1931 to scout for the New York show and—already a fervent fan of Mies’s cool lines and well on his way to becoming a Nazi sympathizer—decided that Mendelsohn’s work was but “a poor imitation of the style.” (He judged adherence to “the style” according to a checklist of features: volume was privileged over mass, regularity trumped absolute symmetry, and applied ornament was eschewed. Abstract aesthetic considerations also took precedence over all other concerns.) He was grousing specifically about Am Rupenhorn, which was built in a more angular mode than Mendelsohn’s usual rounded structures yet didn’t adhere slavishly to the strict rules associated with “the style,” and so maybe seemed to Johnson to suggest the architect’s faulty grasp of its principles. But the doctrinaire young American seemed also to have been irked in a more general way by Mendelsohn’s searching and contextually variable approach. The unabashedly sensuous presence of his buildings, their playful sense of motion and stasis held in balance, their fluid interaction with their surroundings—whether a busy street or a placid lake—were perhaps just a touch too expressive, too free, maybe a little too … Oriental. (It also probably didn’t help that when Johnson turned up in Berlin that summer and placed a call to Mendelsohn, the busy, testy one-eyed architect decided he had far better things to do than waste time chatting with this rather aggressive trend hunter whose questions he considered trite. And so he hung up.)

Was this the beginning of exile or was it the end? The once champagne-toasted architect of neon-and-car-filled Berlin had to wonder as he camped out in a Jerusalem hotel room and sketched round the clock. Luise had fled the “crackle of drawing paper” that “controlled the atmosphere,” and swept off to Cairo for a few weeks of sightseeing before returning to England to help their daughter, Esther, plan her wedding, leaving him alone with two draftsmen to render perspectives and site plans for Weizmann and Schocken, as he also contemplated their future, their people’s future.

Though he worked, he said, too much, he found time to marvel at the pair of rainbows that appeared over the Old City one day—“a mystical image,” with “no present. Only past and future. Unforgettable in the gray white rainy air, edged with desert-gold sunlight.” He also paused to take in the sweet scent of the winter flowers that had sprung up all around—the fragrant crocus and starlike Christ’s tears. These colors, these plants, these smells moved him, and (when he managed to put down his 6B pencil and look up) he continued to circle the prospect of staying put, writing to Luise: “What obliges us to live in a northern country?… Isn’t our place here—isn’t Palestine for eighteen million … the only island?”

But he wasn’t really asking her. Neither was the fate of all the world’s Jews his primary concern. He answered himself in the same letter, mostly with himself in mind: “I am resolved to remain here. Every day I come to regard the people in the fields … even the European Jews who inhabit the hotel, a little more as my brothers.” It seemed to take real effort for him to feel that kinship—and in fact, when he was franker with himself and with his wife, and when he admitted both his passion for the stark Jerusalem hills and his revulsion at the crude construction he saw being thrown up in slapdash fashion across them, he sounded less tentative and sentimental and more like himself: stubborn, irascible, blisteringly honest.

A few days after his initial trip to the site of the possible hospital and expanded university, Mendelsohn returned for another look, with camera, pencil, and what he called the “eye—food of the soul.” Eager to frame his master plan against the backdrop of the Old City, the architect was prepared to be swept by the view, to let his excitement pour forth in a first, bold sketch.

But instead of lifting him up and inspiring him, this visit prompted from Mendelsohn nothing short of an epistolary howl:

“I have visited all the buildings on Mount Scopus. A God-given piece of country between the Dead Sea and the Mediterranean has been violated by devils’ hands. A wretched, botched fruit of incompetence and self-complacency.

“I feel like Jeremiah—deeply depressed and wounded in my soul. And this continues and makes me obstinate, hard and insecure.”

He had, in other words, decided to stay. He would need to find a more suitable office.