He had always experienced what he called “visions.” The word appeared throughout his earliest letters to Luise, and in an unpublished memoir written much later in life she described the jolt of first meeting him when she was just sixteen and he was a twenty-three-year-old architect in training—himself something of a vision.

She felt “uneasy but captivated” at “suddenly being exposed to a very strong personality,” brimming with emphatic ideas about Bach’s architectonic sense of order, The Birth of Tragedy, and the way women’s ball gowns flow. He wore strange clothes—a specially made suit that he had himself designed, with “trousers … tight and cut in the way sailors wear them.” Looking back across the century she’d remember them as “what are now called bell-bottom[s].” He had long hair, combed back, those ever-present spectacles, a large nose, “energetic chin,” and what she considered a beautiful mouth: “Everything about him was unusual. He seemed to me to be someone from an entirely unknown world.”

If he was a kind of Prussian Martian, these visions that gripped him were like radio transmissions from that far-off planet. They seized him at odd moments and seemed to take control, to possess him. Luise would later recount how, soon after the outbreak of World War I, he’d called her to come see him, “as something of fundamental importance had happened to him during the last days. The first sketches of an architecture in steel and concrete had overcome him. In the middle of war cries, terrible events in Belgium, invasion of the Russians in his homeland, the flight of his family to Berlin, he was sitting there, bent over his drafting table, obsessed by the impact of visions which would not leave him for a moment.”

During the war, he was posted to the Russian Front, where he sketched furiously, living, as he put it, “among incessant visions.” He slept little, drew feverishly, and arranged with his commanding officer to take nighttime guard duty in order to devote himself to rendering these imaginary buildings—towering silos, mammoth factories, monumental water towers. These weren’t intended for actual construction, but he needed somehow to fix them on the page in all their elastic, massive grandeur. Tracing paper was in short supply, so—huddled in the cold and dark dugout, men dying nearby—he drew tiny versions of these enormous edifices (one inch equaled a thousand feet) and sent the phantasmagorical miniatures to his new bride, writing her that “the visions are once more behind every ring of light and every corpuscle in my closed eye. Masses standing there in their ripeness flash past in a moment and slip away.” In the trenches, as he’d later put it, “my architectural dreams are the only reality.”

Such single-minded concentration would serve him well in Jerusalem. No matter the tumult taking place all around him—strikes, curfews, explosions, people massing in the streets—he could be found alone in a pool of lamplight, his face almost touching the paper on which he was working. A good deal had changed, however, since he reckoned with those architectural apparitions in the trenches. Now renowned as a planner of actual (not imaginary) buildings, he had a lengthy CV, a business partner, many assistants, elegant sans-serif letterhead, and a style for which he was widely known and that was often imitated.

He’d also had ample chance to consider the danger of such unchecked visions, which often gave way to delusion. Solid as all those buildings and his reputation so recently seemed, he’d become acutely aware of the fragility of these constructions, the shakiness of the ground on which they stood. Who could blame him if—just as he once imagined beams and walls, windows and bricks being raised high in Stuttgart and Berlin, Chemnitz and Cologne—he kept picturing them tumbling down, reduced in an instant to a mere heap of German dust?

* * *

However black his musings were, he was by nature compelled to create. To be an architect is, almost by definition, to imagine what still could be. And in his case, that meant not just envisioning a bright new future but reckoning with the lessons of the past, in all their darkness and complication. “Although my pessimism has always unsettled you…,” he wrote to Luise, “I feel as if, at important moments, I carry an infallible seismograph inside me, which is responsible for my absolutism, for the optimism of my political and artistic convictions.”

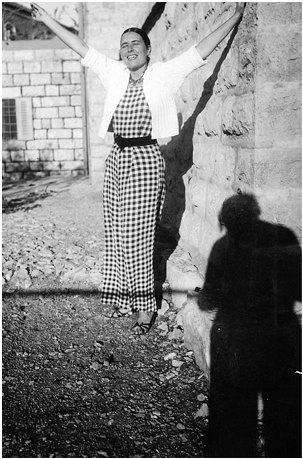

Old-new Jerusalem seemed especially ripe for his canny syntheses of what had been and what might be, and within days of visiting Mount Scopus with Yassky, he’d poured onto paper a series of remarkably embodied preliminary sketches for several major projects to be built throughout the city—an important university building, the villa and library for Schocken—while the Hadassah complex, a bank on the Jaffa Road, and the master plan for the whole Mount Scopus ridge were already taking dramatic shape in his mind. So were plans for the fresh start he’d resolved to make with Luise in Palestine. “If possible,” he wrote her from an airplane high above the clouds, “it will be England and the East for us at the same time.” To this letter, written in German, he appended an English aside: “What a life!”

In April of that next year, 1935, he returned to Jerusalem to establish an office and found himself at once fueled and frayed by the impatient rhythms of the place: “In Berlin it took me twenty years, in London two years: here—or at least that is what my clients demand—it must not take more than two months.” No sooner had he checked back into the King David Hotel than “the rush begins.”

The local tendency toward a kind of barely controlled chaos wasn’t at all what he was used to, but he claimed to revel in the intuitive challenges the place posed. “The Orient,” he declared to a friend, “resists the order of civilization, being itself bound to the order of nature.” Yet this was why “I am so strongly attached to it, trying to achieve a union between Prussianism and the life-cycle of the Muezzin. Between anti-nature and harmony with nature.”

Idealized as it may have been (the term “orientalism” wasn’t yet considered pejorative), his desire for East-West fusion found expression most tangibly in the form of the Jerusalem building with which he fell in love the moment he saw it during his first week back. Located on the fringes of the new neighborhood called Rehavia, a five-minute walk from downtown, this sparely furnished, wood-cupola-capped windmill would serve as his office and his home with Luise for as long as they lived in the city. Initially they negotiated what he called “a life between poles,” making the three-day-long trip by plane to London every few months; later, Jerusalem would be their only home.

_fmt.jpeg)

When he wrote her to tell her he’d rented the bladeless mill, he praised its proportions but didn’t mention the fact—which Luise herself would note with a shiver in her memoir—that it bore an uncanny resemblance to his first building, the Einstein Tower. It was as if, more than fifteen years in advance and a world away, he’d somehow conjured it. Meanwhile the mill was in every respect the opposite of another of his earlier architectural visions, that other dream house, Am Rupenhorn.

Gone were the designer tea trays, the retracting glass walls, the mechanical guardian angels. Gone was the Purism. The mill was constructed simply, in the local style, with thick walls of rough-hewn Jerusalem stone. An enormous fig tree shaded the rambling grounds and dropped seedy-sweet fruit everywhere. A basic outdoor staircase led to an attached wing of low domes and a roof terrace, whose uneven, undulating outline seemed to belong more to a Palestinian peasant house than to the contemporary, decidedly bourgeois “European” neighborhood on whose outskirts the building sat. Rehavia occupied an area once known by the Arabic name of Janziria, and comprised a large tract purchased in 1922 by the settlement arm of the Zionist movement from the cash-strapped Greek Orthodox Church. Designed as a garden suburb by Mendelsohn’s Munich classmate Richard Kauffmann well before Mendelsohn arrived in town, Rehavia had already emerged along its orderly grid, but its houses were still taking stylish shape one by one. Donkeys hauling stones and tools traipsed by every day, in fact, kicking up billows of dust. Though this expanse had until recently been mostly rocky fields and olive groves, some fifty years before Kauffmann began drafting his street and park plans, the Greek Church had built the windmill, and it stood on the edge of the modern Jewish quarter as a silent reminder of other, older forms.

But Eastern as its foundations were, the building was now also swept by strong Western winds. Erich hired another Erich, Kempinski, a highly experienced German-born civil engineer, to run the office. And Kempinski in turn hired assistants—another engineer (Naftali) and four architects (Wolfgang, Gunther, Hans, and Jarost)—who spread out their neatly rendered floor plans and worked downstairs in a large octagonal space surrounded by several small rooms, “monks’ cells,” one of which became Mendelsohn’s private architectural retreat. A Dr. Wolfgang Ehrlich was employed as the firm’s secretary and occupied another of the cells. There he filed blueprints and correspondence and kept the accounts; a young woman named Lilly typed letters in several languages on Mendelsohn’s new stationery, which listed English, Arabic, and Hebrew addresses in both Soho’s Pantheon and Rehavia’s windmill. The sounds of rustling papers and German murmuring filled the air.

Upstairs, Luise decorated their living quarters in a deliberately, almost defiantly, rustic manner, covering the floors with straw mats and the sofa with white canvas, scattering baskets of fruit and vases filled with flowers across the deep windowsills. A huge bed and voluminous mosquito net took up almost all the space in the upper room. The only concessions to their former brand of luxury were the curtains of Damascus silk and the continued employment of the housekeeper, Melli (also German), who, as Luise put it, “came with the mill.” Melli’s face was sweet but she was round as a dumpling, and ever-opinionated Erich couldn’t “bear ugly, old or fat women,” so Luise promised “to dress her in such a way that she would look like part of the windmill.” As if Melli were an oversized doll left by the previous tenants, Luise outfitted her with a little white cap so she appeared “something out of a fairy tale, like the good mother in Cinderella.” The former Berlin socialite seemed to enjoy playing a game of Palestinian village house.

The mill had no refrigerator, no running water. Water was scarce throughout town, and most of what the Mendelsohns had of it, they chose to use on the oleander and cypress they placed in barrels ranged across the terrace. They also filled the garden to spilling with jasmine, cactus, and a deceptively plain-looking Queen of the Night, which waited until dark to drench the whole compound with its fragrance. Wildflowers proliferated.

The windmill was—as Luise would pronounce it decades later—“perfect.” By which she seemed to mean both that they felt more buoyant there than ever before and that she enjoyed the slightly scandalized attitude of some of their Berlin-Jerusalem acquaintances, who “were not able to understand” how she “who in their eyes was so spoiled, would prefer to live in a primitive windmill than in one of the newly built apartment houses.”

Erich was less concerned with social niceties. He seemed grateful simply to have found such a refuge, such freedom, such possibility—to be able to spend his days working inside such a structure. Eager to absorb its dimensions, he wanted to learn the local vernacular, so to speak, by actually living inside it. Both by choice and by necessity, here in Jerusalem he would begin a new, more humble architectural chapter of the literal bildungsroman that was his life, and in a way the mill would be his teacher.

“I am,” he wrote that year, “building the country and rebuilding myself. Here I am a peasant and an artist—instinct and intellect—animal and human being.”

In fact, all kinds of building and rebuilding were taking place, closer to home. One day, resting on their gigantic bed and staring up at the ceiling, Luise noticed a trapdoor, which she discovered led to a tiny, hidden room at the very top of the house. A “dark and dirty dome” guarded by a glint-eyed owl and filled with the cracking wheel and rusting chains of the mill’s old grinding apparatus—now “dangerously deteriorated and capable of breaking loose at any moment”—it seemed almost to hold the building’s unconscious, the suppressed memory of the floury function it once performed. It scared her.

Erich, meanwhile, had a knack for turning such darkness to light. He meant to render the long-forgotten hutch functional again and soon converted it into a private aerie, building a staircase toward it and cutting a window to let in the breeze. The space had just enough room for his drawing board, a chair, and a gramophone. He listened to Bach while he worked late into the night, and the music—Luise would one day write—made the whole mill sing.

* * *

As Mendelsohn looked hard and learned from the mill—studying its scale, the thickness of its walls, the nature of its stone construction—he wanted his employees to do the same: to perceive where they were with a vengeance.

Inviting Julius Posener, a younger architect who once worked in his Berlin office, to take up a job with him in Jerusalem, Mendelsohn forbade him from traveling by boat straight from Marseille or Trieste to Haifa. Posener didn’t “know the Orient,” so Mendelsohn ordered him to go slowly and follow the land route, starting at the Bosphorus. He wanted him to soak up the topography, take in the foliage, contemplate the buildings of Constantinople, of Asia Minor, of Syria. “Otherwise,” according to Posener, later in life, “I’d be of no use to him.”

Disobeying the master, Posener soon reported for duty at the windmill fresh off the Marseille boat, and Mendelsohn greeted him by asking what he had seen on his journey.

The young man had to admit, sheepishly, that he’d seen nothing at all.

Finding this an unsatisfactory answer, Mendelsohn ordered him to start work with a two-week vacation and commanded him to go out and observe all he could of the country—preferably on foot.

These demands were a matter of principle. Mendelsohn believed fiercely in the need to absorb the local landscape through both the eye and the soles of one’s solid European shoes. He insisted architecture shouldn’t change abruptly at passport control, though each local setting had its own strict demands: Jerusalem’s severity wasn’t the same as “the lighthearted character of the plains” around Rehovot, near the coast. But each of these settings shared essential characteristics with others, well beyond the country’s borders. “No one,” he’d write while on a brief 1937 trip to Capri, “ought to build in Palestine who has not first studied the rural buildings of the Mediterranean.” And for Mendelsohn, that Mediterranean was not just the site of pretty whitewashed Greek villages or of imposing Roman ruins, but an Arab place, a living place as well. “Will Palestine develop an architecture of its own?” he’d ask elsewhere, at around the same time. “Certainly, and as an integral part of its very nationhood. Will it be Western? Of course not. Palestine is in the Orient, of the Orient.”

Mild as that sounds, it was a view considered suspect—even somehow treasonous—by many of his colleagues, especially those who’d banded together in Tel Aviv to plot what one of the most prominent of them gleefully called “architectural revolt.” Modeling themselves on the Berlin “Ring” of modernist architects (to which Mendelsohn himself had belonged), and given to the not so new Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity, recently celebrated by forward-thinking architects throughout Europe, they referred to themselves (in Hebrew) as “the Circle,” but they added a combative twist, in honor of the Palestinian target on which they’d set their sights. They saw themselves as soldiers of an architectural sort, conquering the land and wielding as their weapons wet cement and silicate blocks, brise-soleils and pilotis. They weren’t violent people, but when he later described their activities, one of the Circle’s leaders, Polish kibbutznik and Bauhaus graduate Aryeh Sharon—who would go on to become the architect of the fledgling state of Israel, author of the country’s first master plan and head of a “brigade of planners” under the command of David Ben-Gurion—casually adopted the rhetoric of battle. One architect was remembered as “a courageous fighter for pure building cubes”; they were credited with “infiltrating into the well-established architects’ and engineers’ association.” They presented “a common front” and “dared to attack sharply and openly the existing conventional attitudes,” and so on. Eager to banish all trace of the old, the sentimental, the “primitive,” and—worst of all—the “Oriental,” they meant, it seems, to vanquish both their own humbling diasporic history and the more recent (Arab) history of this country. Posener himself would eventually join this group and—taking up a slightly gentler tack—praise this new breed of European-born Jewish architects for “freeing their dwellings from the memories of the past.”

Warlike or willed as their forgetting was, they were, to be fair, also serious people and some of them quite gifted. Trained like Sharon at the Bauhaus, or schooled in the style of Le Corbusier or by Mendelsohn himself (several of these architects besides Posener got their start in his Berlin office), they were devoutly committed to their work, to socialism, and to the Land of Israel. As firmly as Mendelsohn believed, they believed. They believed in cooperative housing estates and kibbutz dining halls; they believed in trade unions and in the Workers’ Health Fund. They believed in chicken coops, the melon crop, Dead Sea potash, and the General Federation of Jewish Labor. They believed in their city, Tel Aviv, and many of them designed buildings there of striking intelligence and modest grace. Their Hebrew was fluent, or getting there. Many of them viewed Mendelsohn as a foreigner and as a snob—and he did little to persuade them otherwise. Though proud to be a Jew, he called himself an English architect. He considered himself an artist, not a soldier, and certainly no Socialist. He built villas for rich and powerful men, not housing for the workers. He never (ever) sat in cafés; he considered the only worthwhile circle the kind he traced with his pencil and compass. He’d chosen to live and build in the antiquity-obsessed city of Jerusalem, to their minds a moldering and unnervingly Eastern place. There he had not only turned his back on concrete (their material of choice), he’d embraced the use of local limestone, whose various types and dressing styles—tubzeh, taltish, musamsam—didn’t even have names in Hebrew. In the raw parlance of the native-born quarry workers, the hardest grade is actually called mizzi yahudi, for the legendary toughness of the yahudi, the Jew.

He had a schoolboy’s knowledge of the language of his fathers, those tough Jews, but didn’t bother to try to speak it in the street. Instead he carried on in German and in his oddball new English. He said he saw political hope for the Jews of Palestine only in “close collaboration with the Arabs.” His wife was often abroad, in London or on one of her regular vacations in Zurich, at the Salzburg festival, in Milan, in St. Moritz. And not only did he himself jet in and out of the country every few months—sometimes bearing for Luise a bouquet of fresh-picked wildflowers, which he entrusted to the stewardess for proper inflight storage—he enjoyed frequent private dinners with Wauchope at Government House. On these occasions, duly noted in the “Social and Personal” column of the English-language Palestine Post, the high commissioner served champagne; he and Erich admired the view of the Old City walls and listened to Bach records together.

When, soon after his arrival, the Circle asked Mendelsohn to send them “a few of his impressions” of Palestine for publication in their Tel Aviv journal, he was curt. “The principal hope of the Jewish people is the building of its national home in Palestine,” he started predictably, then continued in a sharper key: “A great part of this building is of an economical character. The world, however, will not judge us by the amount of citrus fruit exported, but by the spiritual value of our spiritual contributions.”

But perhaps the truth about the world’s judgment rested somewhere between their well-stacked orange crates and his lofty metaphysical aspirations, a compromise Mendelsohn—for all his vaunted vision—could not see. He wasn’t, though, wrong to worry about the aggressively amnesiac thrust of much of the building taking place around him. “We have,” he mused from his windmill perch, “a lot of rethinking yet to do in Palestine.”