PALESTINE AND THE WORLD OF TOMORROW

Now that Mendelsohn had finally made up his mind to be here and only here, in Jerusalem, there was very little for him to do. War seemed imminent, and in a matter of months he’d put the finishing touches on all the major projects that had consumed him for the last several years.

Declared “A Record of Speed and Efficiency” by The Palestine Post, the construction of his government hospital in Haifa took place in a relative flash. Commissioned in August 1936, it opened its doors in December 1938. Although Mendelsohn spoke proudly of the way it “follows the sweep of the blue bay and the tender contour of Mount Carmel—the real one,” the design of the hospital had also made him extremely uneasy. His first and only government commission in Palestine had required him to follow British Colonial Office regulations and separate the wards into those for “white people” (English citizens and soldiers) and “natives” (Arabs and Jews). It was, he’d write a few years later, as the tensions in Palestine continued to mount, “a policy which does not seem to be producing amity in Haifa at the moment.” In fact, the only patients to use the hospital were English and Arab. Because of British policies in general—and segregation at the hospital in particular—Jews would boycott the hospital until 1948.

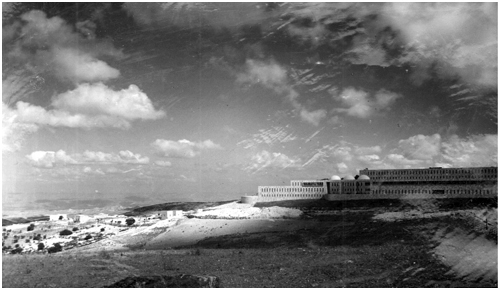

Troubles, though, loomed all around, and they tended to overshadow Mendelsohn’s ostensible architectural triumphs—or throw into very curious relief the festivities that surrounded them. Against what had often seemed insurmountable odds, building at the medical center on Mount Scopus finally came to a close in May 1939, though this fact was relegated to a small second-page item in the local newspapers, pushed to the side by the endless anxious coverage of the immigration-restricting White Paper, which would be announced and loudly denounced that very same month. Again Yassky and Mendelsohn led a large group of journalists and dignitaries around the Scopus site. This time, however, the tour was a subdued affair, “as, under present circumstances,” according to one report, “it was not thought proper to hold a large-scale celebration, but to go ahead with the work on hand in a quiet and business-like fashion.”

In fact, some celebrating did take place, but it did so behind closed doors. On the occasion of the Hadassah inauguration, the Schockens held an “at home” for a hundred carefully selected invitees. (After praising the project and its various patrons and planners, the host offered a toast to Mendelsohn, the medical center’s architect, and, as it happens, architect of the very room where the guests milled and sipped their drinks.) And Erich and Luise themselves threw a reception to mark the buildings’ completion and the arrival in Palestine of the exiled German conductor Hermann Scherchen, an old friend. He had come to lead the Palestine Symphony Orchestra in multiple concerts over several months. His first appearance in Jerusalem was dedicated to Bach, Busoni, and Bruckner, and after various speeches in the maestro’s honor, as one newspaper account had it, “dancing in the floodlit Windmill continued until dawn, when Mr. Mendelsohn conducted a party over the newly completed building of the Hadassah University Medical Centre of which he was the architect.”

But it was hard to keep dancing as the bombs went off. Hours after the White Paper became official, the Irgun detonated a car battery packed with explosives at the Department of Immigration on Queen Melisande Way, and the next day peaceful protests in Jerusalem devolved into rioting, with Jewish mobs smashing shop windows near the government buildings downtown and shooting to death a British policeman. The battle between the stone-throwing throng and the baton-wielding police raged on for three hours, and when the crowds at last dispersed, barricades of stone, large pieces of corrugated iron, wood from a telephone booth, iron girders, and box springs lay scattered across the road. Since the stampeding hordes had gone to the trouble of destroying all the streetlamps in the area, the city center would remain submerged in darkness for weeks.

In the ensuing May days, large nonviolent demonstrations continued, though within a month two more bombs exploded at an Arab-owned movie house on nearby Princess Mary Avenue (later renamed for a Jewish queen, Shlomzion), shattering every pane of glass in the building, blowing the doors from their hinges, blasting a crater in the floor, and injuring eighteen audience members, most of them Arabs. “WRECKAGE AT THE REX” screamed the headlines.

After that particular bombing, all the Jewish cinemas and cafés in town were ordered closed by military order and “as a punishment for the firing by Jews upon Arab buses,” certain Jewish buses were grounded as well. But a homicidal sort of routine had already taken hold, as the Irgun planted four more bombs near the Jaffa Gate, killing five Arabs and injuring nineteen; a young Jewish woman tried to sneak a bomb in a picnic basket into the middle of a crowd of Arabs who’d come to visit their relatives at the Central Prison on a Friday afternoon. Several days later the Irgun targeted the brand-new general post office a few streets away and planted three gelignite packages there, including one that detonated in the face of the very same British sapper who’d managed to defuse the bomb at the prison.

He was killed instantly and an enormous hole blown in the counter, its place taken by shattered glass, mangled steel supports, and broken blocks of concrete. Large chunks of ceiling had collapsed and now lay strewn across the marble floors of the main hall, completed with fanfare just a year before.

* * *

But construction and destruction were—are—bound together in this city to an almost perverse degree. The week the post office bombs exploded, Mendelsohn’s newest building opened right beside it on the Jaffa Road, and the same newspaper whose pages were otherwise filled with accounts of “wanton sabotage and tragic loss of life” proclaimed that “today another monument in stone may be hailed as evidence of past achievement and hope of future progress.” Even as the rubble from the post office blast was being cleared, the seven-story perpendicular and low attached block that together formed Mendelsohn’s Anglo-Palestine Bank admitted customers for the very first time.

Long before all hell broke loose next door and the newly built bank tower provided troops of the British Black Watch with a convenient perch from which to patrol the riots, he’d conceived this two-part structure as a way of reckoning with both the highly uneven terrain and strict town-planning bylaws. The horizontal in the back kept to permitted height while the tall, clean-edged portion that faced the busier street called to mind, he hoped, the “stark verticals” of the traditional buildings of Hebron. All in all, he meant the bank’s variable levels to invoke, once more, the gently stepped villages of the Judean countryside. Curved window grilles, the narrow strip of a long, mounted flagpole, the massive embossed bronze doors, and dozens of slender torch-shaped sconces all punctuated the imposing yet unfussy façade in terms that Mendelsohn himself described in typically elevated fashion. In a newspaper article meant to introduce the bank building and explain yet again his architectural approach to a probably distracted and/or skeptical public, he wrote that “he who knows the Mediterranean Sea—not only from Tel Aviv—who remembers the coloured stone fronts of Venice and Damascus and at the same time the button-like bronze ornaments of the Florentine Palazzi and the contrasting colour scheme of Jaffa’s mosque will recognize the interchange of naked and ornamental stone walls as the true nature of the house of a nobleman or an important business firm.”

Reading his words now, three-quarters of a century later, there seems something overly solicitous in these attempts to articulate the power and dignity that he meant to convey with his building. He didn’t need to sound quite so defensive. As he and all his readers knew, the bank represented a major Zionist institution. It was also the most centrally located building he’d designed for the city so far, occupying as it did—and still does, all these years later—a pivotal spot on the modern town’s main street.

Yet Mendelsohn seemed to realize better than anyone just how little his grand ideas about bronze ornaments and contrasting color schemes, to say nothing of Florentine palazzi and the stone fronts of Damascus, really mattered to most of those who’d deposit checks and arrange for loans at this bank. What counted right now were political symbols, facts on the ground, ideological bottom lines. And though it went completely unmentioned in his article, published a mere week after the explosion, the bombing next door seemed to have rattled him, as in his very opening paragraph he made a point of describing his bank in relation to the post office, which was “the most frequented public building [in the city]” and one whose “architectural importance is of a great artistic value.”

It shouldn’t have come as a surprise that the terrorists had set their sights on the post office. The largest and costliest government building constructed by the British in Palestine, it stood as an obvious emblem of Mandatory rule, and for those enraged at the White Paper and violently opposed to all it represented, the building seemed an ideal target.

What the terrorists didn’t and couldn’t see, however, and what Erich Mendelsohn himself was painfully aware of was that while the post office was certainly meant to be a substantial, formal, and very English structure in all ways, it also bore the subtle private stamp of its builder, the veteran British government architect Austen St. Barbe Harrison. A highly refined and reclusive lifelong expatriate whose work and temperament drew him out of England and to the East as a young man and whose extensive knowledge of Islamic and Byzantine building informed even his most stately colonial structures, Harrison had lived and worked in Palestine for fifteen years, beginning in 1922. The post office, his final finished project in the country, was also his final statement about the possibilities of building there. With its neatly staggered blocks of hand-cut stone from the quarries of the nearby Arab village of Beit Safafa, its arched windows and ornamented wooden doors, its Syrian-styled stripes of alternating black basalt and pale gray ablaq masonry, the post office was and would remain a structure that—like Mendelsohn’s own throughout the city—draws from traditions both Eastern and Western, local and foreign, ancient and modern, and fuses them all into a somehow dynamic and logical whole.

But why, really, should the bomb-wielding brigades of England-loathing Revisionists have cared about any of that? Harrison was neither a Jew nor a Zionist, and if anything, all his fine feeling for “Arab” architecture made him doubly suspect in the eyes of those determined to forge a Jewish state in blood and fire. In the brutal new context of national score settling that had seized hold of Palestine these past few years, there was no place left for a sensibility as singular and circumspect as Harrison’s, a fact he himself had grasped and taken to heart. By the time the high commissioner snipped a ceremonial ribbon, stood to the strains of “God Save the King,” and proclaimed the post office open for business the previous summer, Harrison had vanished from Palestine and the Colonial Service both, tiptoeing away as quickly and quietly as he could.

While the Anglo-Palestine Bank building itself was unlikely to be the target of Jewish terrorists—the first part of its name aside, the bank was more or less the financial arm of the Jewish state in the making, working to acquire land, develop agricultural settlements, and plan urban neighborhoods of a distinctly Zionistic sort—Mendelsohn felt the need to defend Harrison and his building, for reasons at once political and aesthetic. Of course he was, in a very real sense, also defending himself and the vision of a cosmopolitan Jerusalem that both he and Harrison had aspired to create. As he did so, he was, too, standing up for a way of being in the world and with other human beings—not only other Jewish human beings—and of living outside the mental ghetto that this place was quickly becoming. Connected through friendship to Mendelsohn’s old Mediterranean Academy colleague, the sculptor and typographer Eric Gill, the two had sometimes socialized. (Gill had visited Palestine twice in the last several years, working on a series of bas-reliefs for Harrison’s Palestine Archaeological Museum and a rounded “tree of life” for the side of Mendelsohn’s Haifa hospital.) Though they weren’t exactly close, and their personal and architectural styles were quite distinct, they seemed, during Harrison’s time in Palestine, kindred spirits. Before his departure, in fact, Harrison was perhaps the only other architect working in Palestine whom the highly critical and none-too-modest Mendelsohn considered his peer and equal.

With Harrison’s hasty exit from the Jerusalem stage, Mendelsohn was even more alone than before: “Your leaving Palestine for good has greatly affected me,” he wrote the British architect in early January 1938, c/o Cook’s Travelling Office, Cairo, “because I always felt and emphasized that your works are of the highest value to Palestine and should stand for ever as examples of your great mastership of bridging the past and the times to come.”

But Mendelsohn’s work, too, spanned centuries. And on Jaffa Road, the stone walls of his post office and Harrison’s bank remain poised in charged conversation—with each other, with the street where they stand—even now, long after their builders have gone.

* * *

Around the time that Harrison fled Palestine, Mendelsohn’s friend and patron Arthur Wauchope also announced his resignation, and a different high commissioner replaced him—one far less inclined to sip champagne, listen to Bach, and arrange for architectural commissions with a freethinking Jewish free agent like him. Under the new regime at Government House (another of Harrison’s slyly ageless buildings, built just a few years before), “the book shelves no longer housed the poets,” according to one British eyewitness, “but cheap editions of crime novels.” While the dandyish Sir Arthur had played host to a nearly nonstop salon throughout his years in Palestine—with concerts, cocktail parties, and art all around—his replacement, Sir Harold MacMichael, had other, more basic tastes and counted as his “hobbies” “maps, reading detective stories, collecting semi-precious stones and cutting down trees.”

Soon after, Salman Schocken also started preparing to leave. A gradual process, which began with extended trips abroad to raise funds for the Hebrew University, it would end when he decamped in October 1940 on one of those junkets and simply didn’t return. Although he had recently transplanted his eponymous publishing house to Tel Aviv from Berlin—where it had been looted by Nazi gangs in the wake of Kristallnacht and was eventually forced to close—he’d been eyeing the exits from Palestine for some time now.

Like Mendelsohn, he’d found himself increasingly at odds with this rough-and-tumble setting. Before Hitler’s rise to power, he felt, he said, “in the mix” in Germany. Here in Palestine he was outside any such a mix. The politicians saw him, he complained, as someone who just gave money; they didn’t turn to him for advice. Although he had invested seriously in the revival of secular Hebrew intellectual culture, he hadn’t ever really learned the language, and despite his ostensibly powerful position as publisher of one of the country’s leading newspapers and head of the university’s board of trustees, he lived on the cultural margins, which is to say in the very villa that Mendelsohn had built according to his exacting Prussian specifications. While the house once provided shelter from the harsh context in which it was constructed, its marble floors, lavish gardens, and elegant swimming pool now seemed only to underscore the fact that he did not belong here. There was a certain irony in this belated realization. The Schockens had wanted a sleek little palace just like Am Rupenhorn. Mendelsohn had provided it. And as with the dream house Erich built for Luise on the shores of Lake Havel, the Schockens abandoned this Palestinian version after a few scant years.

With Schocken’s going, a part of Mendelsohn went, too.

* * *

In Europe war had finally erupted, and this far-off conflagration had in a way banked the local fires. It wasn’t that Palestine’s problems had gone away, of course, but that they’d been temporarily muffled. “We are still in the midst of peace which the outbreak of the war has made—a contradiction in itself—a real one,” wrote Erich to a British friend at the start of 1940. “Internal strife has completely stopped and we enjoy again the beauty of the country’s first spring: the cover of fresh green, an abundance of flowers and oranges with which even the most greedy ones cannot cope.”

Besides eating all that plentiful citrus, though, Erich didn’t have much to do. He’d recently wound up work on a cavernous research laboratory that Chaim Weizmann entrusted to him at his institute in Rehovot, and he had completed a commission for an agricultural college in the same town. But in the frustrating absence of other old allies and new commissions, he felt isolated and idle, and so turned his thoughts to rendering plans for a different kind of structure, one for which he’d be both patron and architect: an edifice made of words.

“Palestine and the World of Tomorrow” was, for Mendelsohn, an unusually rickety construction—a slender yet unwieldy pamphlet, written in his awkward and often overblown and misspelled English and privately printed in Jerusalem, February 1940. Whatever it lacked of his usual architectonic grace and control, however, the short essay more than made up for by way of passion, ambition, and—that old obsession—vision. More directly than ever before, in fact, it set forth his most vatic prescription for the political and cultural future of the land, and in a way what he wrote there brought him full circle, back to those “explosions of imagination” he was so desperate to capture on small slips of paper while stationed as a young soldier on the Russian Front. Whether or not anyone would actually build what he planned was, in other words, almost beside the point. Convinced of the worth and originality of his ideas, he was determined now to fix them on the page for their own sake.

Urgent manifesto, rambling disquisition, fervent plea—the pamphlet begins by offering a sweeping view of no less than six thousand years of Mediterranean history, from Egypt’s invention of the alphabet to the Phoenicians’ creation of coinage to Judaism’s formulation of “the moral law,” and so on, through Roman civics to Greek philosophy and dramatic poetry. For centuries, he writes, “the Mediterranean basin retained its place as the master of the world,” and Palestine functioned as “a perpetual highway for the nations ruling the Mediterranean. Its history is tied up with the fate of those great empires.” Meanwhile the “remains of its Architecture and Art” he writes, capitalizing his nouns in Germanic fashion, “reflect these manifold invasions and their influence upon its civilization.”

At its heart, the architectural legacy of these empires is syncretic. He finds traces in the destroyed Jewish Temple of “a culture moulded by Babylon, Egypt, and Minoan Crete,” and sees everywhere the remains of Rome, early Christianity, and Islam. Such glories, though, belong to the distant past, and just as the whole region gradually fell into decline, so did Palestine become little more than “an unimportant trade route to the Far East.”

He blames the sorry state of things on the Industrial Revolution as much as on geography or Turkish rule, and after a protracted woolly ramble over the ensuing centuries and some convoluted sloganeering, Mendelsohn comes around to the actual subject—and point—of the pamphlet, which isn’t really about architecture at all but the chaotic condition of the cosmos right now, and the possibilities this crisis offers, both for the world and for the Jewish people.

With the Emancipation, the Jews of Europe believed they might become part of the societies in which they lived, but “the nationalist and racist hatreds of the last decades” showed this hope to be misguided. Given their “national feeling, based on an undying belief in the prophecies of the Bible,” Palestine was the only answer. After he waxes rhapsodic about “the return of the Jews to … the country of their historic origin,” praising the idealism of the early settlers and the “epic battle” waged during the first five decades of “Zionist colonization,” he abruptly shifts gears. In light of current events, the idea of an independent state is, he says, too narrow.

“Palestine is not an uninhabited country. On the contrary, it forms a part of the Arabian world.”

And here he bursts forth into his most explicit call for action: Jews must “become a cell” of what he calls “the future Semitic commonwealth.” This new entity should take its cues from the culture that found expression when the Arab empire was at its height and Arabs and Jews were the “torchbearers of world enlightenment.” While Europe languished in the Dark Ages and the Jews there huddled in ghettos, the Jews of the Arab world rose to powerful political positions and created lasting works of art.

Once again, he proclaims, the time has come to bring about a “reunion of matter and spirit.” The Jews, he says, “return to Palestine neither as conquerors nor as refugees. That is why they realize that the rebuilding of the country cannot be done except in communion with the original Arab population.” Surveying the tumultuous years of British rule, he declares that the Mandate has run its course and that a new model is necessary.

“The gate to the Semitic world,” Palestine today symbolizes “the union between the most modern civilization and the most antique culture. It is the place where intellect and vision—matter and spirit meet. In the arrangement commanded by this union both Arabs and Jews … should be equally interested. On its solution depends the fate of Palestine to become a part of the New-World which is going to replace the world that has gone.”

“Genesis,” he ends with a roll of rhetorical thunder, “repeats itself.”

Or does it? Although cast in the soaring terms of a collective credo, “Palestine and the World of Tomorrow” seems in many ways a last-ditch display of willfully wishful thinking on Mendelsohn’s part—an oracular howl, or cri de broken coeur. Given all that he’d witnessed in the past several years, he knew very well just how unrealistic this vision was. Obsessed as he’d been with absorbing the physical and climatic details of the place, he seemed to have given himself over one last time to the most airborne sort of illusion, as if he could pretend that all he had long imagined for Palestine were in fact the case. “The Jews,” he writes in bizarrely sanguine fashion, “seem to grasp the fact that Palestine can only be built up in close collaboration with the Arabs and that she can become a place of well-being only in case both peoples come to an understanding.” His rousing call for a peaceful and artful Semitic Commonwealth isn’t so very far in the end from Else Lasker-Schüler’s plan for a conflict-resolving waffle stand and Arab-Jewish amusement park.

On the other hand, even as he held forth publicly about his great hopes for the land and the world of tomorrow, he was also privately mired in the same old doubts and even despair, to say nothing of restlessness. “I think that Palestine must necessarily be a center for the Jews…,” he wrote Lewis Mumford at around this time, but “the scale of the land is very small, and its population is divided into two camps—politically and intellectually. There is no opportunity for me as architect to propagate the ideal values of my work … And so I often wonder whether America could not be my field of activity.”

* * *

Choosing to leave Jerusalem was far less dramatic than deciding to stay.

Because of the constant delays brought about by the “disturbances,” and Hadassah’s regular demands for revision of his plans, the Mount Scopus commission had cost him a great deal of extra time and money, and now that it was complete, he wrote Yassky in the spirit of their “close and harmonious collaboration” to ask if—as he said had been promised him by a gentleman’s agreement at the project’s outset—they might now offer him additional payment: “Even the most malevolent could not claim that your Architect has been paid according to his abilities, faithfulness, and achievements.”

Yassky agreed and tried to intervene with the board. And though he praised Mendelsohn’s conscientious work and described the “rather precarious” state of the architect’s finances, those in charge of the checkbooks were unmoved. Rose Halprin, chair of the Palestine Committee, could offer only a primly maddening letter in which she informed Mendelsohn that Hadassah had decided not to pay him any more, though “we need hardly point out that in no wise is this a lack of appreciation of the great achievement for which all thanks are due you.” Payment, after all, was secondary, as “we know how much gratification you have derived from serving Palestine through the erection of the Medical Centre. We are happy that public acknowledgment has come to you for your share in the work…” and so on. This cheerful brush-off was enough to send Mendelsohn into an apoplectic fit. He shot back that he had “for years devoted” his “technical and artistical ability to Hadassah’s work without thinking of the disastrous financial clauses of a contract” he’d been “persuaded to accept.” They had given him a promise in which he’d trusted.

“Your letter, dear Mrs. Halprin, has shattered my confidence and I must leave it at that, if Hadassah does not find her way to do justice to my cause. Words of praise and promises for the future cannot change my attitude.”

He’d continued to take on piecemeal work for the university—completing designs for a modest gym and nearby playing field in 1939 and, together with Schocken, judging an architectural competition for a small museum there. But it was now perfectly clear that with Schocken gone and Magnes hostile to him, he wouldn’t be planning the campus as a whole. He asked for the return of his scale model for his “collection of unrealized projects” and in turn the university asked him—without a hint of shame—for a cash donation. While there were again murmurings about arranging for him to teach architecture on Mount Scopus, with Weizmann even telegraphing Schocken at his new perch in New York’s Delmonico Hotel, SORRY HEAR MENDELSOHN MAY BE LEAVING PALESTINE … SUGGEST TRY UTMOST CREATE CHAIR FOR HIM AT JERUSALEM SO AS SECURE HIS SERVICES FOR COUNTRY—nothing came of that. In Wauchope’s absence, talk of entrusting him with “guiding” the country architecturally and planning “all the important buildings” had also evaporated.

“Palestine and the World of Tomorrow” had, meanwhile, only confirmed his most scornful critics in their sense of him as a detached snob and dangerous fantasist, if not an outright traitor. “He made himself very unpopular in Palestine with this brochure,” Luise would later write, “but … Eric was not a diplomat and it was his whole personality to say what he thought was right. It did not make life easier for him, or for me.”

All of these disappointments ached internally. There were, however, other, outer reasons why Erich and Luise began to consider packing their bags yet again. In September 1940, Italian bombs struck Tel Aviv and the surrounding Arab villages and killed 137 people. Rommel and his troops were soon in Libya, creeping closer, and, as Luise would explain, “It seemed clear to us that when they would reach Palestine, a terrible slaughter of the Jews would occur. We had not escaped the fury of Hitler to be delivered to his fury in Palestine.”

And yet … while all of these factors contributed to their eventual departure in March 1941, none of them alone satisfactorily explains it. If anything, Mendelsohn had come full circle, returning to the same sense that gripped him, back in 1933, that “Palestine did not call me.” He was still waiting to be called. And perhaps not surprisingly, even after they’d gone—making their way first to New York and finally to San Francisco, where he found his practice confined mostly to the design of suburban American synagogues and his mood increasingly melancholy—the decision to leave was never quite final.

Over an ocean and the course of several years, he and Yassky continued to correspond warmly, though when in 1945 Mendelsohn suggested the possibility of returning to Jerusalem, should the proper commissions present themselves, Yassky sounded like he’d reached the frayed end of one very long rope: “It is up to you to reconcile those two parties, namely, Jewish Palestine and Mendelsohn. You realize that this reconciliation cannot take the form of Palestine’s inviting Mendelsohn to come here. The reconciliation may take place when Mendelsohn humbly comes to Palestine as many thousands have done before and many thousands dream of doing now … I should be extremely sorry to see that what I mistook for your sincere desire to return to Palestine was conditioned by the number of projects which you might or might not be asked to undertake. That, my dear Eric, is a peculiar Zionism with which I personally can have nothing to do.”

This letter pained Mendelsohn deeply, and he responded, “I left Palestine financially poorer than when I arrived … I have never looked at Palestine as a source of fortune as I haven’t become an architect to be a rich man. I left Palestine when the outbreak of the war stopped every building activity without which … I would have become humiliatingly dependent. I have never deserted Palestine nor will I ever desert her ideals.”

In fact, he’d never return in body, though in a very real way, he’d remain there, or his singular eye would, and will: Circles and cycles abound. On the mountain where the two men squinted out at the astonishing view together on that windy day in 1934, his hospital would continue to stand, long after both of them did. In it, Else Lasker-Schüler would draw her last breaths in January 1945. Driving up in an armored convoy toward it, Chaim Yassky and seventy-seven doctors, nurses, patients, orderlies, and others would be slaughtered in a notoriously grisly attack by Arab forces in April 1948, four days after Jewish forces slaughtered in a notoriously grisly attack some hundred Arab residents of the nearby village of Deir Yassin and a month before Israel declared itself a state.

“If I had the chance, I would begin again,” Erich Mendelsohn wrote a friend in March 1953, “letting my earliest sketches guide me, considering all I have done since a preparation for a final, newly creative period.” The next month, his doctors would discover a tumor in his thyroid gland (a different cancer from the one that took his eye three decades before), and after he died quietly that September at San Francisco’s Mount Zion Hospital, his ashes were scattered to the California wind.