9

Fine-tuning the Clock

WHILE WE MIGHT ALL ASPIRE to regular bedtimes and regulated light exposure over 24 hours, this isn’t, of course, always feasible: we travel and get jet-lagged, we work shifts.

And no one travels further or experiences a more unusual relationship with light than astronauts living in space. So, if we want to learn how to optimise our physical and mental performance – and reduce the risk of illness or injury under challenging light and sleep conditions – we could do worse than to look to NASA.

From space, the sunrise begins as a convex blue streak in the blackness, marking the border between night and day. The streak extends outwards and grows wider, turning whitish at its crest as a yellow puddle forms at its base, which quickly ignites into a golden, ten-pointed star. The star grows steadily brighter, until the blue streak looks like a ring set with the biggest and brightest diamond you’ve ever seen, and as this blazing diamond – our sun – moves higher, the clouds, ice caps and deep-blue ocean of earth begin to roll into view. This dazzling view of our planet is short-lived, however: within three quarters of an hour, the expanding curtain of light has shrunk back and been consumed by a tide of blackness, that spreads across the earth as if in pursuit of the vanishing sun.

This spectacle plays out sixteen times a day for the astronauts of the International Space Station (ISS), as they chase around earth at a speed of 27,000 km per hour in order to avoid dropping out of the sky. At this speed, they complete a full orbit of the earth every 90 minutes, which means that they’ll see a sunrise or sunset every 45 minutes.

The experience becomes more visceral if they step outside the space station and propel themselves across its surface to carry out essential repairs or maintenance. When the sun is in view, the temperature in space is a blistering 121°C, and when it sets, it plummets to –157°C. Although their spacesuits and thermal layers provide some insulation, these extremes are still keenly felt.

For the most part, however, astronauts are enclosed within the confines of the space station where, apart from some small portholes, and the seven large windows of the cupola – the station’s viewing deck – the light is dim. Circadian desynchrony is a major problem for ISS astronauts because the light-dark cycle they’re exposed to is so unusual. The ISS is darker than most indoor working environments on earth, and the frequent rising and setting of the sun complicates things still further: ‘If you go to the cupola right before going to bed, and you look out and see sunrise or sunset, you just got 100,000 lux,’ says Smith L. Johnston, a medical officer and flight surgeon based at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. ‘You’re not going to be able to sleep for two hours because you will just be buzzed.’

On top of this, ISS astronauts often work long hours under high stress to complete their tasks, and must sometimes work ‘slam shifts’, involving an abrupt change to their sleep schedule to accommodate, for example, a shuttle docking, or to complete a prolonged and technical piece of construction work.

However, NASA’s astronauts don’t only have to contend with circadian desynchrony when they’re in space. Their training plans are laid out eight years in advance, and almost every minute of their time is accounted for. These include frequent trips to Moscow, Cologne and Tokyo for training: ‘They can’t have two weeks of downtime to recover from jet lag every time they go to Moscow,’ says Steven Lockley, a sleep expert at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

NASA takes sleep and preventative medicine extremely seriously. Having spent billions building a space station and training the astronauts to fly it – and scarred by the 1986 Challenger shuttle disaster, which killed all seven crew members, and was partially attributed to the culture of excessive working hours and sleep loss – they don’t wish to see it undermined by someone falling asleep on the job. ‘Nobody gets the kind of work-up our astronauts get each year, apart from pro-athletes, because once they’re in, they’re such a valuable highly trained commodity that we do everything we can to fly them,’ Johnston says.

One area that NASA has focused on since 2016 is an optimised LED lighting system on board the ISS, designed to improve astronauts’ sleep and alertness, so that they can rapidly adapt to slam shifts and the unusual conditions of space. Inside each coffin-like crew cabin, you’ll find a sleeping bag plus personal items, and these new adjustable, colour-changing lights, which have three settings. Before bed, the astronauts use the ‘pre-sleep’ mode, which has had the blue part of the light spectrum removed; when they wake up in the morning, they can get an alertness boost and strengthen their circadian rhythm by flipping the switch to a much brighter, blue-enhanced light. This setting is also deployed to help shift the clock forwards or backwards if an astronaut needs to change their sleep schedule because of work demands. During the rest of the day, the lighting on the ISS is blue-white.

Similar principles are applied back down on earth, to help staff in mission control adjust to the night shift: ‘Some of them may not be used to working at that time, so when they take a break, every 90 minutes, we let them go in a room, walk on a treadmill, and they get exposed to a bunch of blue light,’ Johnston says.

We can learn a lot from NASA’s approach to fighting jet lag, as they have turned it into a fine art. Jet lag, and the sleep deprivation it causes, play havoc with concentration, reaction times, mood and mental abilities. Lockley is employed by NASA to draft up separate, jet-lag-countermeasure plans, detailing when astronauts should be seeing light, and when they should be avoiding it; when they should take melatonin or make use of caffeine; and, in some cases, when to eat and exercise.

The general rule is that it takes a day to adjust to every time zone you cross, but Lockley claims that, with appropriate light timing and melatonin administration, it is possible to shift people by two to three hours a day – this would mean getting over the jet lag from a London to New York flight in two days, rather than four or five days.

To do this, you need to ask yourself two questions:

- What time does your body clock think it is? To figure out when you should be avoiding or actively seeking out bright light – or taking melatonin if you have any (it’s not currently available in the UK) – you need to think about what time it is in the country you’re leaving behind. This is the time your body clock is currently set at.

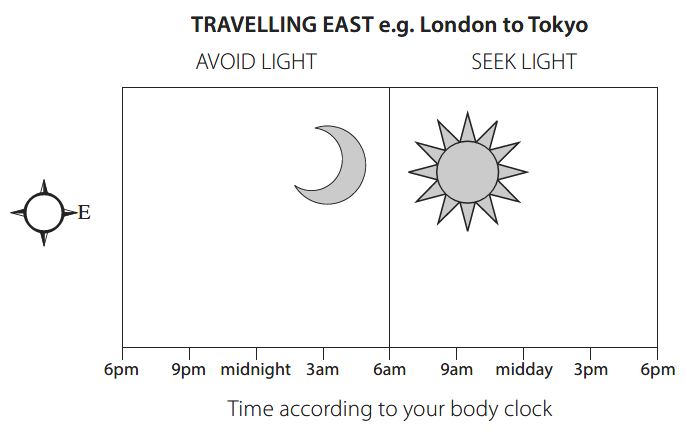

- Do you want to advance or delay your clock? If you’re travelling east, you’ll want to ADVANCE it, which means becoming more of an early bird. This means avoiding bright light when your body thinks that it’s night-time and seeking it out after 6 a.m. in your old time zone.

How to Minimise Jet Lag

Being exposed to light between 6am and 6pm in the time zone you’re leaving behind will advance your body clock, which is useful if you’re travelling east. The effect is greatest at around 9am. Seek out light during these times, and minimise light exposure between 6pm and 6am in your old time zone (particularly around 3am) by wearing wrap-around sunglasses, or sleeping if this coincides with night in your new time zone.

If you have melatonin, take before 1am in your old time zone.

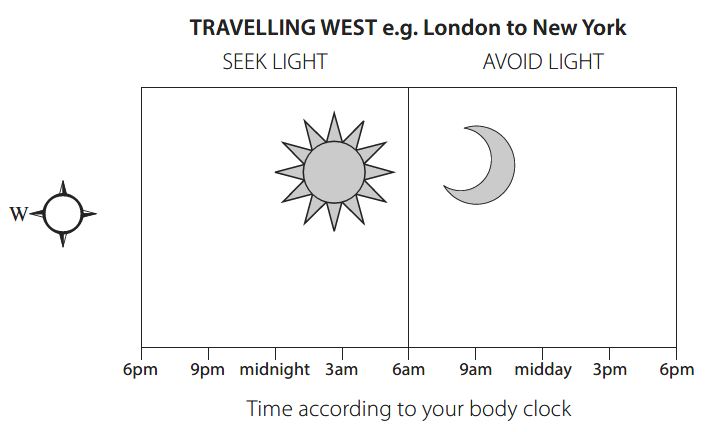

Being exposed to light between 6pm and 6am in the time zone you’re leaving behind will delay your body clock, which is useful if you’re travelling west. The effect is greatest at around 3am. Seek out light during these times, and minimise light exposure between 6am and 6pm in your old time zone (particularly around 9am) by wearing wrap-around sunglasses, or sleeping if this coincides with night in your new time zone.

If you have melatonin, take after 1am in your old time zone.

If you’re travelling west, you’ll want to DELAY your body clock, which means becoming more of a night owl. This means seeking out bright light when your body clock thinks that it’s night-time and avoiding it after 6 a.m. in the country you’re leaving behind.

In both cases, you should be going to bed and waking up at your preferred sleep time in the new time zone.

Let’s use a London to Tokyo flight as an example. During the winter months, Tokyo is nine hours ahead of the UK, which means advancing the body clock by nine hours, and becoming an extreme early bird by British standards. Say your flight leaves at 7 p.m. (UK time), and takes twelve hours, you will be arriving in Japan at 4 p.m. local time – but what matters to your body clock, is that it’s 7 a.m. UK time. To advance the clock, you will therefore need to avoid light exposure for almost the entire flight, and only seek it out at the very end (after 6 a.m. UK time). One way of doing this would be to invest in a pair of dark, wrap-around glasses, which you’d try to wear at the airport, in the run-up to boarding your flight, and certainly once you were on the plane (aircraft cabins are full of artificial light). It would also be wise to try to sleep throughout the flight, using an eye mask. Melatonin can help people overcome jet lag, but only if it’s taken at the right time – in this case, you’d take it just before boarding the flight, reinforcing the sleep signal.

From 6 a.m. (UK time), you should remove your glasses, and actively seek out bright light. You will probably be exhausted, but the good news is that you only need to stay awake until your preferred bedtime in your new time zone. In the run-up to bed, avoid bright light, take some melatonin and, hopefully, get a decent night’s rest.

With a far-flung destination, such as Japan, you would face an additional problem the next morning, because although your body clock may have advanced by two to three hours, it will still lag behind Japanese time. People are often advised to get outside and start living on their new time zone as soon as they arrive in a new country, but in this case, doing so would be counter-productive. The sun may be up in Tokyo, but your body clock still thinks it’s nighttime. You want to carry on advancing your clock, but seeing light now will delay it, so you’ll need to put your sunglasses back on and avoid light until after lunch. Because of this issue, when travelling very long distances, it makes a lot of sense to start trying to shift your clock a few days ahead of travel, by going to bed progressively earlier in anticipation of travelling east, or progressively later if you’re going to be travelling west.

Several apps are coming on to the market that will do these calculations for you. Lockley is even about to launch one himself. Because of scientific disagreement about exactly how long it takes to shift the clock, though, these apps sometimes give slightly conflicting advice. But in all cases, the same principles apply: it’s the time zone that your body clock thinks it’s in that matters.

* * *

Another field at the forefront of jet-lag management is that of elite sports, where frequent travel clashes with the urgent need for peak performance. Rest and sleep are critical to athletes – as attested by well-known sportspeople the world over, notably Roger Federer who is reported to sleep for nine to ten hours per night. But it’s not only about feeling sleepy or wide awake at the wrong time of day: jet lag is yet another form of circadian misalignment. If clocks in muscle cells fall out of synchrony with those in the brain, or in tissues that regulate the supply of fuel to the muscles, then their strength, coordination and reaction times can also suffer. Yet professional athletes spend their lives circling the globe to compete.

The American basketball coach Doc Rivers remembers clearly the moment when he finally appreciated the importance of the body clock to his players’ performance. Watching his championship-winning team, the Boston Celtics, being hammered by the Phoenix Suns (who had a reputation for sloppy defence), he began wondering if his players were drunk, they were so bad. Rivers became so incensed, he was sent off the court himself, after arguing with the officials.

Yet months earlier, the sleep expert Charles Czeisler had predicted that the Celtics would lose this very match, thanks to a gruelling pre-game schedule that would see them flying straight from a game in Boston to one in Portland on the Pacific coast the following night; and then immediately flying east to Arizona (which is in yet another time zone), to take on the Suns. Czeisler had even warned Rivers that this game would be akin to watching drunken basketball. He should have listened: the Suns eventually beat the Celtics 88–71.1

In a game like basketball, millisecond differences in players’ speed and reaction times can make a massive difference to the game’s outcome.

Since 2016, the sleep expert Cheri Mah has been collaborating with the US cable and satellite sports channel ESPN, on its ‘schedule-alert’ project, which aims to predict those basketball games that will be won and lost on player exhaustion.

To do so, Mah weighs up individual teams’ travel schedules and game density – both of which can affect players’ sleep and physical recovery – to come up with the forty-two games providing the biggest competitive disadvantage to one of the teams. The idea is to raise awareness about the importance of sleep to athlete recovery, but gamblers have also been cashing in on some of Mah’s predictions.

During the first year of the project, Mah made a correct prediction 69 per cent of the time; and in the case of seventeen ‘red alert’ games where the competitive disadvantage was judged to be particularly steep, the accuracy of her predictions rose to 76.5 per cent.

The idea that jet lag might affect athletic performance isn’t entirely new, though. One of the first studies to examine it began as a spot of lunchtime fun between several University of Massachusetts neurologists in the mid-nineties. Frustrated at the lack of data to illustrate the physical effects of jet lag, they turned to the trove of North American baseball records to examine whether travelling between the East and Pacific coasts (a journey that involves crossing three time zones) had any impact on game outcomes.

Eastward travel is generally considered harder on the body than travelling west, because it requires people to go to bed and wake up earlier (essentially shortening their day), when for most of us, the natural inclination is to stay up later – probably because our body clocks tend to run slightly longer than 24 hours. This tends to make travelling west a little easier to cope with.

The baseball results supported this notion: visiting teams – who tend to be at a natural disadvantage because they are playing away from home – won 44 per cent of games if they had travelled west, but only 37 per cent of games if they had travelled east. Playing in their own time zone was best of all, though: here, visiting teams won 46 per cent of games. Another group recently extended these findings, analysing more than 46,000 baseball games played over twenty years; they showed that the normal ‘home-field’ advantage was all but eliminated if the home team had recently flown more than two time zones east (and were therefore suffering from jet lag), and the visiting team was from the same time zone.

Mah has also quantified the benefits of longer sleep for athletes: in one recent study she found that by extending baseball players’ sleep from 6.3 to 6.9 hours for five nights, they experienced a 122-millisecond improvement in cognitive processing, which – given that a fast ball takes roughly 400 milliseconds to travel from pitcher to hitter – could provide considerably more time to assess the speed and trajectory of the ball’s flight.2 In another study, she found that when college basketball players committed to trying to get ten hours of sleep per night, rather than their usual six to nine hours, they showed a 9 per cent improvement in the accuracy of their free throws, and a 5 per cent boost in sprinting speed.3 Again, this may not sound like much, but in professional sport, where the margin between winning and losing is so slim, athletes will grasp any competitive advantage.

Sleep and circadian misalignment aside, physical performance also has a circadian rhythm, which closely follows the daily rise and fall in body temperature and alertness. Muscle strength, reaction times, flexibility, speed: all tend to peak in the late afternoon or early evening.

The evening is when most sporting world records have been set; it’s also when swimmers swim fastest, and cyclists take longer to pedal to exhaustion. For sports involving more technical skills, such as football, tennis or badminton, performance tends to peak a little earlier, during the afternoon; this is when footballers have been shown to chip, perform keepy-uppies, juggle and volley with the greatest precision. Few athletes are at their best in the morning; although tennis serves tend to be more accurate then, they are faster in the evening.

These circadian differences are less important if you’re exercising for fun or general fitness, although exercising in the early morning could carry a greater risk of injury, so it’s worth spending more time warming up at that time of day. However, if you’re seeking to gain a competitive advantage, or to set a personal best, time of day really does seem to matter.

It’s also an important consideration for athletes competing at an international level, because crossing time zones will alter the timing of their peak performance. Take English rugby players: studies have shown that they are faster and stronger in the evenings, but if the England team flies to New Zealand to compete against the All Blacks, suddenly their performance will be better in the morning – at least until their body clocks adjust. Therefore, many athletes will travel to their destination country a week or so ahead of major competitions in order to give their bodies time to adapt. The clever ones may also tweak their training schedules, to get used to exercising at the time of the competition.

That’s if they want to be at their sharpest. The American ski-jump team is rumoured to actively court jet lag: if you’re planning to fling yourself off a giant ramp strapped to a pair of skis, it could pay to be a little foggy in the head, to get over the fear. ‘You let muscle memory take over,’ one US ski jumper commented.4 ‘Sometimes that’s better than thinking about what you need to do.’

* * *

Beyond managing the impact of jet lag on whole teams, some sports are beginning to delve into an even more complex and emerging area: chronotyping their athletes.

Although grip strength peaks at 5.30 p.m. on average, it will peak a little earlier for morning types, and a little later for evening types. It’s the same with other physical and mental attributes. ‘I might tell a coach – these are the players who could perform a bit better during day games, and these are the players who might perform better during night games – although I don’t think anyone has ever been stopped from playing a game because of that sort of information,’ Mah says. ‘I think coaches intuitively know that so-and-so plays terribly in these types of games, because they’ve looked at them for so long.’

Naturally, NASA is ahead of the game on this and already ‘chronotypes’ its astronauts – categorising them as early, intermediate, or late types, based on their preferred sleep times – and will sometimes use this information when devising shift-work schedules or deciding when a specific piece of work on board the ISS should take place.

Imagine a world where every employer did this: where night owls could start their day later, to ensure they were properly rested, and team meetings were scheduled for when everyone was likely to be mentally alert and receptive. This seemingly utopian dream may not be so far off for the inhabitants of one sleepy German spa town.