Most people remember the defining moment of the 1983 season because of the Pine Tar game. That was when George Brett homered against the Yankees, then went ballistic when the umpire called him out because pine tar extended too far up on his bat.

To me the Pine Tar Game holds an entirely different meaning. I injured my left shoulder that afternoon when I tried to make a diving catch in the outfield. I was in the clubhouse getting treatment when George hit the home run. It was the final game of a series against the Yankees and we were going home. I had an appointment with Dr. Steven Joyce the following day to have him look at my shoulder.

I’m driving in to his office down on the Plaza from my home in Blue Springs, (Mo.) and I’m having a nice little conversation with myself as I’m driving.

“You’re a young kid.”

“You’ll be all right.”

“Maybe it’s not so bad.”

“Maybe I can get in the game tonight.”

I was listening to music, driving the freeway through downtown and I got off at the Southwest Trafficway exit to head up the hill on toward St. Luke’s Hospital. I came up to a light and gunned the motor to get through on a yellow. This dark-colored car followed me through on the red, and I’m thinking, “That’s good because if the police are going to stop anybody it will be that guy.”

The next light was red, so I stopped. This dark-colored sedan pulled up beside me at the stoplight. I glanced to my left at the two guys sitting in the front seat, probably nodded at them or something because that’s what I usually did. Then, the one closest to me reached into his coat, pulled out a badge, tapped it on his window and pointed over to the side of the road for me to pull over.

I didn’t know what’s going on, but I was nervous and started to sweat. My mind was just racing. It’s funny how much you can think about in such a short time. I know it’s serious. The KBI (Kansas Bureau of Investigation) – which is really just the FBI of the state – doesn’t pull you over for going through a yellow.

My mind immediately raced back eight months in time. I had experimented a few times with cocaine after the 1982 season, but I had quit by December. I realized cocaine made me feel better for a little while, but it wasn’t going to make me a better baseball player. When you’ve done something like that you always have it in the back of your mind that something bad could happen. So, I think subconsciously I kind of knew what it was about.

So, that was going through my mind, but I hadn’t used in about eight months. Surely it couldn’t be that. I didn’t even think about the phone call I had made to Mark Liebl just a month earlier. Why would I? Nothing had ever come of that phone call.

I pulled over, and one of the guys asked me to get out of my car and into theirs. They introduced themselves as agents from the KBI. I don’t remember if there were flashing lights or anything, but I know I felt like everyone who was driving by us would recognize me and know the police were talking to me. Then these guys started asking me questions about Mark Liebl, the guy who I had bought cocaine from back in November.

“Do you know this person?”

“Do you know that person?”

They’re playing “good cop, bad cop” with me. One guy would be real nice and then the guy in the backseat would jump on me real hard trying to confuse me. After the questions, they tell me that they know I had tried to buy $20,000 worth of stuff. Hell, I didn’t have $20,000 to give away, let alone to buy drugs.

This went on for a while, and I was starting to get angry. They’re telling me they know I have done this and done that – stuff I had never done. Finally, I look at the one guy and say, “Well, if you know so damn much and you think I have done this, then arrest me right now. You are telling me stuff that I never did. I don’t even know this guy or that guy you named.”

Finally they let me go, but they said, “We’re going to stay in touch.”

So, I’m just in a fog. What’s going to happen to me? Who knows about this? Has everybody who drove down the street seen me? What am I going to tell my family? I still haven’t seen the doctor, and now I’m late for my appointment to get my shoulder checked out.

I’m just absolutely done, mentally. I’m really down in the dumps.

I got to the hospital, and I was walking into this public place with all these people around. They’re talking to me, asking for my autograph, how the shoulder is ... I’m trying to be civil, and I sign stuff, but I’m also wondering whether anybody knows what’s going on.

I saw the doctor, but honestly, I can’t even remember what the diagnosis was. I don’t have any idea what he said. I finished there, and then I had to go to the ballpark because we were playing the Cleveland Indians that night.

I usually never listen to the sports shows on the radio because someone was always criticizing the Royals or me or something, and I had stopped listening pretty early in my career. But this day I turned it on because I was curious now about whether anything has leaked out or what. And I heard that there are Royals involved in this drug thing and a “Royals superstar” was involved.

As silly as it sounds now, in my brain I was thinking, “Who is the superstar?”

When I got to the stadium I parked behind right field and walked in through the tunnel. As soon as I got to my locker there was a message that I needed to go upstairs to see John Schuerholz, the general manager. I was still in kind of a fog. I can’t remember my conversation with him, but I know it wasn’t a very good conversation.

When I got back to the locker room I remember the players sort of whispering to each other and looking over at me. I was sitting in the corner at my locker, and I was wondering who else might have gotten stopped that day.

I don’t remember whether I played that day or not, but I felt like everybody at the whole stadium was staring at me the whole time and that everybody hated me. I don’t have any recollection of the fans or how they reacted that day, but I was as low as you could go, and I wanted everyone to know the truth.

“I was clean.”

“Yeah, I might have done something, but I had stopped doing it for months by then – damn near eight months.”

I kept wondering, “Why was this happening now, why not when I was doing it?” I was trying to think through everything in my brain. Everything I had worked so hard for might be gone. All the things I wanted to do as a young player and a young man might be over. Would I still be allowed to play baseball? Would I have to go to jail? Would my teammates ever talk to me again? How would this affect the rest of my life?

Worst of all ... I had to tell my mother.

That was harder than dealing with the police, harder than getting stopped by the side of the road, harder than having fans yell at you every day. She was the one who took care of me, who raised me, who put clothes on my back. My mother always wanted the best for us, and she worked hard to get it. So, the disappointment for everyone else was secondary to disappointing my mother and my grandmother. That was a really hard phone call to make ... I mean, really hard.

And you know the only thing she wanted to know.

She told me just one thing, “Tell me the truth, and we’ll get through this.”

I’m telling you, man, that was a rough day.

From that day, all the rest of the 1983 season it was coming out a little bit at a time. It was me then Vida, then Aikens, then Jerry Martin. I am sure the KBI had other people they thought were involved. They were going through the whole team, but I wasn’t really worried about anybody else but me.

What I found out later, which upset me for a long, long time, was that the reason we got caught was because Vida got caught. Vida got caught with the stuff. And to save himself, he told on us. That’s how they started tapping the phone – through Vida.

What upset me most is that he was still on our team when this was happening. I’m thinking, “You couldn’t even tell me something?” You know what I’m saying? “You couldn’t say, ‘Hey, they’re tapping his phone’ or ‘Hey ... something.’” But I guess he couldn’t because it would have messed up his deal.

For a long time I was angry at Vida. Later on when I was with the A’s in 1991 and ‘92, he would sometimes come into the locker room, and he just couldn’t look at me. I wouldn’t look at him, and he couldn’t look at me. One day, he walked over and said, “Man, I’m sorry.” When he said that, I forgave him. I finally let it go.

The whole situation was on my mind for the next month of the season after I was stopped, “What would happen to me?” I knew something bad was going to happen, but the uncertainty of it was just eating at me.

If I got a hit, I didn’t care. If I got two hits, I didn’t care. I just didn’t care.

I mean, I knew something was going to happen. You just know something is going to happen to you when an FBI guy talks to you – or KBI. But it seemed like the investigation was being dragged out and dragged out.

What I could never get my brain around is that nothing got passed to me the day I made the phone call. Nothing got bought. That’s like if you talked about robbing a bank, then somebody robs the bank and they put you in jail for talking about it. That’s what I felt like I was being investigated for.

Finally, they charge me. I think I was in Seattle on a Royals road trip when my lawyer calls and said I had a choice of a felony for alleged distribution of cocaine or pleading guilty to a misdemeanor for attempting to buy cocaine.

My lawyer and I wanted to challenge it, go to trial because I didn’t get anything. I was just talking. I thought I could beat the trafficking charge. My lawyer thought I could beat it. But my agent goes, “If we do that, it will be a long drawn-out trial and probably take over a year.”

We checked with the DA and what they were saying was, “Well, if you cop to this, then we are sure you can get probation.” So, my attorney did the research. He talked to the police. He talked to the DA. He looked up all the cases in the books and no one had ever gotten jail time. One case was a fine; the other was a year probation for what I had done.

I trusted my attorney and I trusted my agent, but they weren’t the ones in trouble. I was the one in trouble.

We had put together a petition and had 10,000 names on it from fans that didn’t want me to go to jail. We had announced a youth drug prevention program with Mr. K. We did whatever we thought we could to help make the sentence a little less.

We go to court, and the judge asks everybody what they thought. So the DA recommends probation. The judge asks if we agree with that, and my lawyer and I said we did. And all the time everyone is talking, the judge was just sitting up there and pouring himself a glass of water like, “I’m not even listening to what you guys are saying.”

I’m sitting there watching him. The courtroom is filled. The buzz is going through. There were TV cameras. It was crazy.

Then the judge looks over and says, “I’ll tell you what I’m going to do. I have people downstairs who don’t get this much attention. They have committed murder and other things. I’m going to give you a year in jail ... ”

That ... is ... all ... I ... hear.

I jump up and say “For what! I didn’t do anything. I didn’t get anything.” I was so stunned and shocked. The lawyer grabbed me and pulled me back down. I never heard the judge say “nine months suspended.”

Then, the judge hits the gavel and says, “Order. Order.” He started talking and I was just in a blur thinking I got to go to jail for something I didn’t even get. I thought if the prosecutors recommended a sentence that was what the judge was going to do.

I learned later that what the judge was saying afterwards is that he sentenced me that way because I was “a national hero who occupied a special place in our society. There are responsibilities you must live up to.”

That’s a responsibility I never asked for. The people might have asked for it. Baseball asked for it. But all I did was sign a contract to play baseball, and that’s my job. I didn’t sign a contract to take care of anybody else’s kids or be a role model for anybody else. I didn’t have athletes for my role models. Well, I did for how they played on the field, but not their private lives. Those are two different things. How can you put those two things together as one?

Even the police were stunned at the sentence. They were shocked. I got apologies as they walked me downstairs to fingerprint me. They were saying, “Willie, we’re really sorry. We didn’t know this was going to happen. We didn’t know it was going to turn out like this.”

The judge had his own agenda. I found out later that he was a third-string jock in some sport and he had to let it go and ended up being a judge. Who the hell knows what his reason was? What I found out later is that they were cracking down so hard on drugs because it was (President Ronald) Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign. They were giving people time for stuff they were just on probation for before.

But I know my life changed from the day that KBI guy stopped me on the street.

From that point on everything that day was foggy for me, and my life changed forever in ways I didn’t even understand at the time. It changed for me, for my family, for the Royals, for every baseball fan who ever heard my name. By the end of the day, I would be embarrassed, have to make the hardest phone call of my life and I was worried that I might never be allowed to step on a baseball field again.

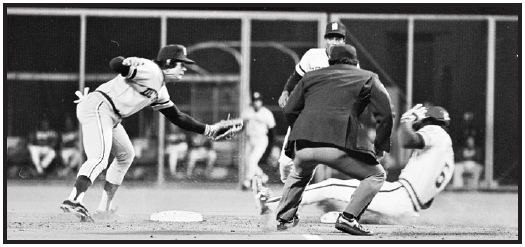

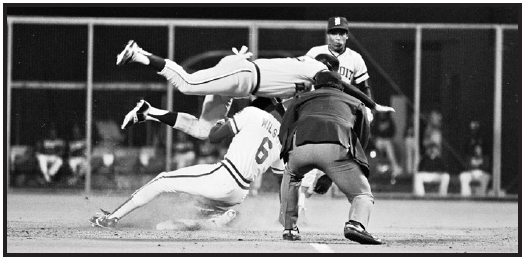

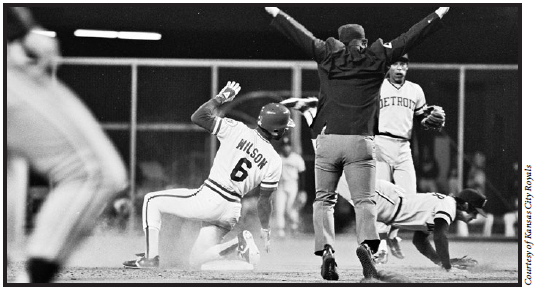

They created the Hal McRae rule to limit hard slides into second base. But I learned the technique pretty well too.

We won the Suburban Conference championship during my sophomore year. I’m third from right on the front row.

This is my sophomore baseball team at Summit High School. I’m in the middle on the back row.

L-R I’m standing with my high school coach Art Cottrell and teammate George Gross. Gross threw a no-hitter while at Summit and later was drafted by the Houston Astros in 1977.

SAFE!

This is my buddy and roommate U.L. Washington. We were teammates in AA, AAA and the major leagues.

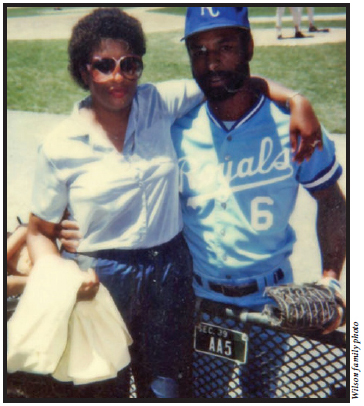

My mother would often travel from New Jersey when we were playing the Orioles.

This is one of the early pictures of me with the big league team in spring training.

Portrait montage painting for Kansas City Royals Hall of Fame.

Sliding into the base was a thrill for me and the crowd.

I was not a natural left-handed batter. But once I embraced hitting from that side of the plate my career really took off.

Frank White and I were among a group of seven who were at the 1982 Major League All-Star Game in Montreal

Bill Cosby was one of the many celebrities who sang “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” when I was playing with the Cubs.

My grandmother, Annie Mae Timothy, “Madear” to the family, raised me until I was 7 years old.

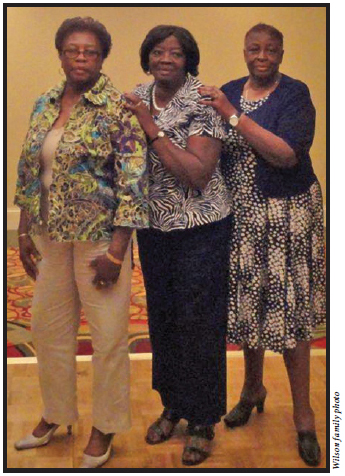

My aunts, Martha Ann Gardner and Lula Mae Gibbs and my mother, Dorothy Lynn, (L-R) at a family reunion in 2010.

This is my daughter, Shanice.

My younger brother, Anthony Lynn.

Here is my oldest son DJ.

Trevor’s son Trey Shawn is my youngest grandchild.

My son, Max, attended a Royals game with me.

My son Trevor and I at the All Star game in K.C.

I love having my children around me (from left) son Trevor, daughter Shanice, granddaughter Anisa, grandson Kayden and son Max.

My granddaughter, Anisa and grandson, KJ (Kayden).

When I was with Oakland, my oldest son would travel to spring training with me. Loved hanging out with him!

Great getting to hang out with some of the current players. Aaron Crow, Eric Hosmer, Everett Teaford and Sluggerrr on a Royals Caravan outing at Crow’s elementary school in Topeka.

2007 Willie Wilson Legends game at CommunityAmerica Ball Park.

I worked with the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum to conduct this clinic for players from RBI.

Explaining the highs and lows of being a Major Leaguer to youth from RBI.

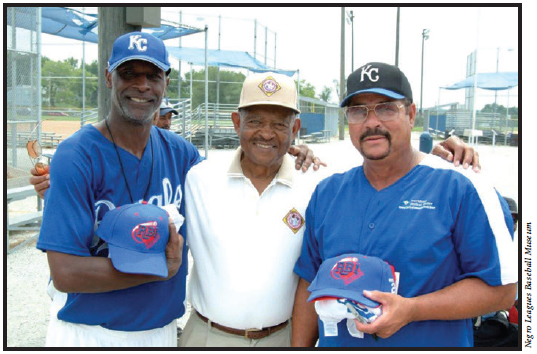

Don Motley of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and former Royal Amos Otis at a RBI clinic.

I’m becoming more comfortable as a speaker with events like this for the Legacy Awards banquet at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

I’m here with (from left) Fred Patek, Al Fitzmorris and Frank White at a State Farm Luncheon benefiting the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

Here I’m talking with former pitcher Bert Blyleven. I can tell you it’s a lot easier facing him here than in the batter’s box.

Jim “Mudcat” Grant (left) can be really entertaining for guys like me and former player Brian McRae.

It was an honor to be among the VIPs at the screening of the movie “42: The Jackie Robinson Story” at its Kansas City premiere in the spring of 2013.

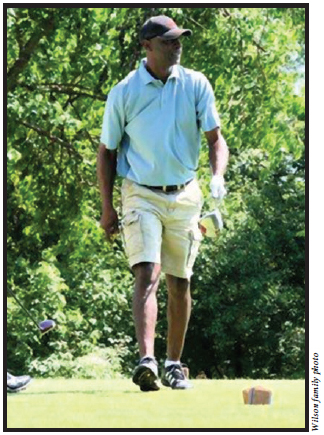

With my baseball career in the background, my sport is now golf.

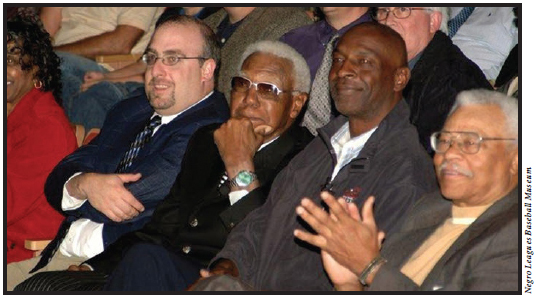

Being around Buck O’neil was always an honor. Here we’re at a Negro Leagues Museum event with Buck’s biographer Joe Posnanski and DeMorris Smith, son of former KC Monarchs player Hilton Smith.