By the end of 1986 it was clear the Royals were going toward being young. They were already trying to move George (Brett) over to first base. In September of 1986, they called up Kevin Seitzer and Bo Jackson, who would both be with the club the next year. In the winter they traded for Danny Tartabull. I think we had Angel Salazar at shortstop.

In spring training of 1987, Dick Howser tried to come back as manager, but he wasn’t able to. So, we had another new manager, Billy Gardner. And we actually got off to a pretty good start. I think we were like 10 games over .500 at the start of July. But there were a lot of things going on that made it really hard to keep that going.

Dick died on June 17, and that took a lot out of the guys who had played for him on the World Series team. By the middle of July, the Royals released Hal McRae and I think that took away a big piece of the heart of that team.

My final four years with the Royals were full of ups and downs.

Hal only played in 18 games because they moved George to first and made Steve Balboni the DH. So, Hal hadn’t been able to contribute like he had in the past. That changed a lot of things he could do for the team. When you aren’t playing, you can’t show people how to play, you just have to talk. With the younger guys they aren’t thinking about what he has done for the Royals in the past, they’re thinking, “What are you doing right now?” For me, and Frank and George and some of the older guys, Hal was the same kind of leader. But not the young guys, and more of the leadership role fell to us.

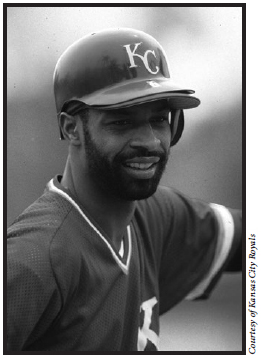

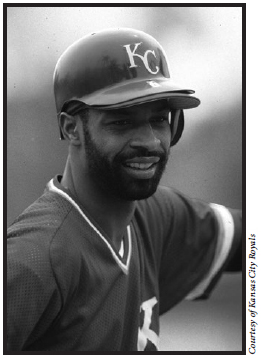

George was an action leader, by example, of how he worked at the game. Frank was more quiet. I was vocal, the angry guy. I wasn’t actively trying to be aggressive or anything, but I think just the way I played showed. I was vocal on the bench. I was vocal in the locker room. You saw every emotion I had out on the field because I let you know it. If I was happy, you knew it. If I was angry ... frustrated ... you knew it. If I got called out, I would show all kinds of emotion coming back to the bench.

But none of us really filled that same Hal McRae role. All those successful Royals teams had several leaders. But Hal was the one guy who everybody looked up to. He was vocal, but he always backed up what he said. If he told you that you had to hustle more, he was hustling more. He had this fire inside of him.

The successful Royals teams had been built by those kind of players, the ones who knew how to win. Amos Otis came over from the Mets right after they won the World Series. Hal came to the Royals right after the Reds were world champions. Steve Balboni, Jim Sundberg, Cookie Rojas, Freddie Patek – they were all veterans with winning experience. When we would bring in younger guys like Frank and George in the ‘70s – and me a little later on – there was still this big group of veteran leaders.

Those were guys who put high expectations on you. Hal used to have this thing where he would hide in one of the laundry carts in the locker room with a sergeant’s shirt on and they would cover him up with laundry. If you were even debating whether you would play that day – whether you were sore or tired or whatever – he would have someone push the laundry cart in front of your locker room and jump and shoot you with the bat, “Brrrrrrrrrrrrrp!”

Then he’d shout, “Why don’t you go somewhere else? We don’t need you if you can’t play! Get out of here!” Meanwhile, everyone in the locker room was watching as he is getting pushed up in front of your locker. So, now they all knew. He would get underneath your skin to the point where you wanted to play so bad just to prove him wrong. At least that’s how it worked with me.

He’d use psychology on you, and he would do that a lot to goad you into performing. He’d be pushing it to the point where sometimes you would just want to punch him out. And then he would cackle, “I’m not going to fight you,” and he would walk away.

On the field, you could see the fire and the desire to play a certain way. You could see the hustle. He would say things to you on the bench, too – quietly sometimes and not so quietly sometimes. His main deal was to win ballgames, and he wasn’t afraid to let his opinion be known.

When we went into that slump after Dick died, Billy Gardner didn’t last real long. Then they brought in John Wathan, who a lot of us had played with as a teammate and who had just retired two years before. So, you had four managers in less than two years. With me it became more of a psychological game because now the manager was a guy who didn’t want me to live in his neighborhood and signed a petition against me back in 1984. I never said anything until he became the manager. I asked him about it and whether he could treat me fairly.

He told me he had not signed the petition – that his wife signed it. I always thought that was a pretty weak explanation of why he tried to keep me out of his neighborhood. He wouldn’t even tell me about it at the time. When I would go to the ballpark I was mentally looking at the manager in a whole different way – and that carried over to 1988, 1989 and 1990.

When John got the job, I remember a meeting when he called all the veterans in – me, Frank, George, Quiz – the guys he had played with a long time. It was like, “I need you guys to help me out and this and blah, blah, blah.” Then, the next few days he wasn’t putting me in the lineup. So, I’m thinking, “How do I help you out if I don’t play?”

Over those few years they were getting rid of the veterans who had been leaders on our team. A year after they let Hal go in the middle of the season, they cut Quiz in the middle of the season.

That was the other thing that was frustrating for some of us was that we were finding out this is the way the organization treated some of their important veterans. I know you get older, and you maybe aren’t as productive, but it was frustrating to know that this is how they treat you at the very end, not with dignity or pride. That’s when you really know it’s a business, and they pick and choose who they want to continue with.

For some of us black players, we were looking at it a whole different way. What we see, in our brain, is that the white guy is getting treated one way and the black guy is getting treated another way.

And I’m not talking about George. We all accepted that George was going to be the man. George was no problem with us because of what he had accomplished. What we couldn’t accept as easily were the people who weren’t as good for the team who went farther in the organization. That’s where we would look at it in a different way.

The way they had released Amos after 1983, flat-out telling him he wasn’t going to be a part of the team while the season was going on. I mean how do you do that to a guy who has been that important to your team? Then you see how they release Hal in the middle of the year, Quiz in the middle of a year. And Bonesy (Balboni), he was our first baseman. You take him out of the mix and put George at first and Seitzer at third. You are messing up continuity – not because you think they can’t play but because you start looking strictly at the numbers instead of the heart of the person. They start to push you off to the side.

The Royals, at one time, had all these dudes who were giving knowledge to young players. Hal McRae, Amos Otis, George gave me knowledge, Cookie Rojas gave me knowledge. Vada Pinson, Davey Nelson, Paul Splittorff, Dennis Leonard – they all taught me things. When I was coming up it was all those dudes giving you stuff, and you saw how they reacted to a loss or a victory and what they did the next time. How they prepared, what was going through their heads.

It was disheartening to see what was happening with the team. When I came up, it was like 21 older dudes and four young dudes, and we were a winning team. Now it’s four older dudes and 21 young dudes, and we weren’t a winning team anymore. We’re not in second or first. We are in last or second-to-last.

For me, when they are letting guys go who I know, I’m losing friends, losing buddies. It’s going to my emotions.

What they were really lucky with were the pitchers. The young guys were coming through at that point. Sabes won the Cy Young Award in 1985 when we won the World Series. He had another good year in 1987 and won the Cy Young again in 1989. They also added Tom Gordon in 1988, another young pitcher who made his mark. In 1989, Kevin Appier came in, and we finished second in the AL West.

In 1989, I could see the beginning of the end coming for me. Bo had been playing more and more center field, and I was in left. Then they brought in (Jim) Eisenreich and he was getting more playing time with Bo and Danny Tartabull. By 1990, Brian McRae had been added to the mix. At second base, Terry Shumpert was getting more and more time as they were moving Frank out.

We could see the writing on the wall from all the moves they started making from 1987 on. They got rid of Hal in the middle of the 1987 season. They also got rid of David Cone and Jim Sundberg that year. They got rid of Quiz in the middle of the 1988 season. That same year they traded Danny Jackson and let Lonnie Smith and Balboni go.

They didn’t give Hal or Quiz any kind of a big send-off. Quiz is one of the guys who put your team on the map, winning a Fireman of the Year Award. We’re looking at it and thinking, “That’s the way you take care of your great superstars? What are you going to do with me and Frank?”

We are trying not to say stuff because we are thinking – hoping – in the back of our minds that maybe we will be different. At least I was thinking that maybe they will treat me a little different.

So, in that last year when they are sort of weaning us out of the lineup, Frank and I would be sitting on the bench. We were getting less and less playing time, but when the game was on the line they would put me in or Frank in. It used to just piss us off – at least I know it used to piss me off. I used to say to Frank, “If they had put me in the game in the first place it wouldn’t be this damn close. Now, I gotta go up there, get a frickin’ hit, steal a base. I could have won that in the first six or seven, not the ninth. Now you are really putting pressure on me.” It was hard.

And I remember one day they were having a “Frank White Day.” I think it was some group outside the Royals out in the community who arranged it. Wathan didn’t have Frank in the starting lineup. All of a sudden, during the game the phone rings in the dugout downstairs and they’re like, “Do you know it’s Frank White Day?”

That cut to the core of me in a lot of ways. How can you not start him?

When we did get to start games, they might take us out. Instead of walking down the steps and up to the locker room, we tried to be a part of the team and sit on the bench and root for the team – trying to be professional. But it hurt like hell.

I was just a little dummy, but I was thinking that they might want players who could pass along experience and knowledge on to the team, but for some reason that regime of Royals people decided they were going to go young. They didn’t think that an eight-time Gold Glover had anything to give. They didn’t think I could pass along knowledge to the young guys they had coming up in the outfield.

That final year with the Royals, 1990, I played in 115 games. The regular outfield was Jim Eisenreich, Bo Jackson and Danny Tartabull. I had the highest batting average of any of the other outfielders, and only George had a higher batting average on the team, but I was expendable. I’ll never quite understand that except that the guy who was the manager just wanted to get rid of me and they didn’t want to pay my salary.