Chapter 10

Avoiding Allergens That Cause Respiratory Symptoms

In This Chapter

Understanding what you’re breathing

Understanding what you’re breathing

Reading pollen counts: News you can use

Reading pollen counts: News you can use

Minding mites and other dusty denizens

Minding mites and other dusty denizens

Knowing how your home affects your health

Knowing how your home affects your health

Identifying allergens and irritants in your environment

Identifying allergens and irritants in your environment

Eliminating, controlling, and avoiding allergens and irritants in your home

Eliminating, controlling, and avoiding allergens and irritants in your home

S omething’s in the air — and it may be affecting your asthma. Under normal circumstances, breathing is a reflex you don’t even think about — as long as nothing in the air interferes with the process. However, unless you live in a bubble, every time you breathe in, you inhale more than just oxygen into your nose and lungs.

In fact, the air that most people breathe is full of many types of airborne particles that are too small for the naked eye to see. In addition to pollutants and other airborne materials, these particles include allergenic substances, known as aeroallergens, that can trigger allergic reactions and significantly affect the well-being of people with asthma or allergies. The inhaled aeroallergens that trigger allergic reactions are known as inhalant allergens.

The following common inhalant allergens are the most frequent triggers of allergic rhinitis (also known as hay fever; see Chapter 7) and asthma. (See Chapter 5 for further information on what these allergens do to people with asthma.)

Pollens produced by wind-pollinated plants, such as ragweed

Pollens produced by wind-pollinated plants, such as ragweed

Wind-borne mold spores

Wind-borne mold spores

Household dust, which can contain various types of allergenic substances, such as dust mite allergen, dander, and other allergenic materials from household pets and pests, allergenic fibers, and indoor mold spores

Household dust, which can contain various types of allergenic substances, such as dust mite allergen, dander, and other allergenic materials from household pets and pests, allergenic fibers, and indoor mold spores

In this chapter, I give you the lowdown on these common inhalant allergens and explain the dangers of each in detail. I also discuss ways you can avoid or at least limit your exposure to these allergens.

Pollens

Pollens can trigger allergic rhinitis and asthma symptoms. Plants that depend on wind rather than insects for pollination — grasses, trees, and weeds — produce pollens. These plants release their wind-borne pollens in huge quantities to reproduce. For example, ragweed plants may release up to 1 million pollen granules in a day, and the massive amounts of pollen granules that some trees release can resemble clouds.

Pollen particulars

A variety of means, including insects, animals, and the wind, provide transportation for pollen granules. Wind-borne pollens that trigger allergic rhinitis symptoms come from three classifications of plants:

Grasses: The grasses that cause most grass-induced allergic rhinitis are widespread throughout North America and were imported from Europe to feed animals and create lawns. By contrast, the many native grasses of North America produce little pollen. I provide more details on these grasses in the “Allergens in the grass” section, later in this chapter.

Grasses: The grasses that cause most grass-induced allergic rhinitis are widespread throughout North America and were imported from Europe to feed animals and create lawns. By contrast, the many native grasses of North America produce little pollen. I provide more details on these grasses in the “Allergens in the grass” section, later in this chapter.

Weeds: The most important weeds that trigger symptoms of allergic rhinitis are those of the tribe Ambrosieae, known as ragweeds.

Weeds: The most important weeds that trigger symptoms of allergic rhinitis are those of the tribe Ambrosieae, known as ragweeds.

Trees: Most trees that release symptom-causing pollens are angiosperms (which means “flowering seeds,” and yet these trees don’t actually flower), such as willows, poplars, beeches, or oaks. Similarly, pollens from a few gymnosperms (naked seeds), such as pines, spruces, firs, junipers, cypresses, hemlocks, and cedars, also can trigger symptoms of allergic rhinitis.

Trees: Most trees that release symptom-causing pollens are angiosperms (which means “flowering seeds,” and yet these trees don’t actually flower), such as willows, poplars, beeches, or oaks. Similarly, pollens from a few gymnosperms (naked seeds), such as pines, spruces, firs, junipers, cypresses, hemlocks, and cedars, also can trigger symptoms of allergic rhinitis.

Although these plant groups account for most cases of pollen-induced allergic rhinitis, only a small percentage of the members of each group has been shown to produce allergenic pollen.

Dead wood

Although you may experience respiratory symptoms when exposed to the pollen of certain grasses, weeds, or trees, that doesn’t actually mean you’re allergic to the pollinating plants themselves. When you’re allergic to oak pollen, you’re not allergic to the actual oak tree. You’re only allergic to the pollen granules produced by the tree. Therefore, even though oak pollen may trigger your asthma symptoms, you nevertheless can use furniture made from the wood of the tree. That antique oak desk in your study won’t trigger your allergies — it stopped pollinating a long time ago.

Blowin’ in the wind

Wind pollination has worked well for certain plants for millions of years, enabling many of them to survive and flourish in environments that don’t provide many insect or animal pollinators. The much younger species of man (Homo sapiens — you and me) has also flourished in these areas, with the result that we’re often in the pollen path of wind-pollinating plants. Instead of wind-borne pollen granules reaching their intended targets, they often end up in your eyes, nose, throat, and lungs, causing allergic reactions in susceptible individuals.

Pollens (and molds) for all seasons

Most wind-pollinating plants in the United States and Canada release their pollens at specific times during the year that can be classified into five pollen seasons. Whenever your respiratory symptoms begin or worsen during one of these seasons, the predominance of particular pollens during that particular time of year may be the cause of the allergic reactions that complicate your asthma. Here’s the type of pollen (or molds) that may affect you in each of the five pollen seasons:

When your symptoms get worse during spring, the probable cause is tree pollen.

When your symptoms get worse during spring, the probable cause is tree pollen.

In late spring and early summer, grass pollen is the likely culprit.

In late spring and early summer, grass pollen is the likely culprit.

From late summer to autumn, weed pollen, especially from ragweed, may cause you problems.

From late summer to autumn, weed pollen, especially from ragweed, may cause you problems.

Especially during the summer and fall but also throughout the year — except during snow cover — mold spores, particularly those of airborne molds, may trigger your allergies.

Especially during the summer and fall but also throughout the year — except during snow cover — mold spores, particularly those of airborne molds, may trigger your allergies.

In winter, wind-borne pollens rarely are a factor in most parts of the United States and Canada. However, in the warmer southern regions of the United States that don’t experience prolonged periods of freezing temperatures (such as southern California), pollinating plants and molds still release allergy-triggering pollen and mold spores whenever there’s no snow cover.

In winter, wind-borne pollens rarely are a factor in most parts of the United States and Canada. However, in the warmer southern regions of the United States that don’t experience prolonged periods of freezing temperatures (such as southern California), pollinating plants and molds still release allergy-triggering pollen and mold spores whenever there’s no snow cover.

Take my pollen, please!

Plants that are the main culprits in allergic rhinitis depend on wind pollination because they’re not pretty or colorful enough to attract insects or other animals to do the pollinating. Most flowers that appeal to people — and to insects and other animals — produce heavier pollens that stick to the insects or animals that carry it to female plant reproductive sites, so you’re far less likely to acquire sensitivities to pollen from roses or other attractive, colorful plants, unless you experience constant, close contact with flowers. When you experience allergy symptoms after stopping to smell the roses, pollens from nearby grasses, weeds, or trees may cause your reaction.

Non-natives

A list of local allergenic plants can serve as a good starting point for figuring out what plants may be affecting your allergies. However, knowing about non-native plants in your environment also is useful. Non-native plants in your environment often include trees and grasses — some of which may also produce allergenic pollen — that may have been planted around your community for decorative purposes.

Counting your pollens

Go west, young pollen!

When I was a boy growing up in New York, I remember my doctor telling patients with asthma and allergies to move to Arizona because of the area’s dry climate and sparse plant population. Through the years, plenty of folks have indeed moved to Arizona (and not just because of my doctor). Many of Arizona’s new residents decided to plant non-native ornamental plants, such as mulberry trees, to spruce up the desert scenery. Mulberry trees thrive in the hot, dry climate and produce clouds of allergenic pollen. As a result, Phoenix and other cities in the state are now major allergy centers. In fact, some of the busiest allergists in the United States practice in Arizona.

Running the numbers

| Category | Pollen Grains Per | Degree of Symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cubic Meter Per Day* | |||

| Absent | 0 | No symptoms. | |

| Low | 0–10 | Symptoms may only affect people with extreme | |

| sensitivities to these pollens. | |||

| Moderate | 10–50 | Many people who are sensitive to these | |

| pollens experience symptoms at this rating. | |||

| High | 50–500 | Most people with any sensitivity to these | |

| pollens experience symptoms. | |||

| Very High | More than 500 | Almost anyone with any sensitivity at all to | |

| these pollens experiences symptoms. If | |||

| you’re extremely sensitive to ragweed pollen, | |||

| your symptoms can be severe at this level. |

*These figures are averages.

Today’s pollen count was collected yesterday and usually reflects what was in the air 24 hours ago.

Today’s pollen count was collected yesterday and usually reflects what was in the air 24 hours ago.

Rain can clear pollen out of the air temporarily. However, short thunderstorms — the kind that are characteristic of late spring and summer in parts of North America — can actually spread pollen granules farther.

Rain can clear pollen out of the air temporarily. However, short thunderstorms — the kind that are characteristic of late spring and summer in parts of North America — can actually spread pollen granules farther.

Hot weather increases pollination, whereas (you probably figured this one out already) cooler temperatures reduce the amount of pollen that plants produce.

Hot weather increases pollination, whereas (you probably figured this one out already) cooler temperatures reduce the amount of pollen that plants produce.

Pollen grains typically are at their highest concentrations from mid-morning to early afternoon.

Pollen grains typically are at their highest concentrations from mid-morning to early afternoon.

Because they’re wind-borne, many pollen granules travel great distances, so the plants in your backyard or your neighbor’s garden may not be what’s triggering your allergies. Chopping down the olive tree in front of your house may have little, if any, effect on your allergies.

Because they’re wind-borne, many pollen granules travel great distances, so the plants in your backyard or your neighbor’s garden may not be what’s triggering your allergies. Chopping down the olive tree in front of your house may have little, if any, effect on your allergies.

Quality, not quantity

Whenever your community reports high counts for pollens to which you are allergic, you can take steps to avoid or reduce your exposure to those pollens. For details on how, see the “Pollen-proofing” section, later in this chapter.

Whenever your community reports high counts for pollens to which you are allergic, you can take steps to avoid or reduce your exposure to those pollens. For details on how, see the “Pollen-proofing” section, later in this chapter.

If complete or significant avoidance isn’t practical or possible, you can use pollen counts to help you determine (based on your doctor’s advice) when to take medication to prevent the onset of symptoms or at least keep them from interfering dramatically with your life. For an extensive survey of allergic rhinitis medication, see Chapter 12.

If complete or significant avoidance isn’t practical or possible, you can use pollen counts to help you determine (based on your doctor’s advice) when to take medication to prevent the onset of symptoms or at least keep them from interfering dramatically with your life. For an extensive survey of allergic rhinitis medication, see Chapter 12.

The most important pollen levels for you to consider are the ones that trigger your allergies. Many people react differently to different levels of airborne pollen, and pollens vary between regions. However, you need to be concerned when pollen counts reach the moderate range, because that’s generally when many people with allergies start to experience symptoms.

The most important pollen levels for you to consider are the ones that trigger your allergies. Many people react differently to different levels of airborne pollen, and pollens vary between regions. However, you need to be concerned when pollen counts reach the moderate range, because that’s generally when many people with allergies start to experience symptoms.

Allergens in the grass

Grass pollens are the most common cause of allergies in the world. Although only a small percentage of the more than 1,000 species of grasses in North America actually produce pollen that triggers asthma symptoms and allergic reactions, these particular species are widespread throughout the continent and release huge amounts of pollen granules into the air. Most of these allergy-triggering grasses are non-native plants that were imported to grow feed for farm animals and for planting lawns.

Wind-pollinated grasses release vast amounts of pollen granules during the late spring pollen season. The most significant allergy-symptom provoking grasses are Bermuda grass, bluegrass, orchard grass, ryegrass, timothy, and fescue. Of those grasses, Bermuda grass may be the most significant allergy trigger. Bermuda grass releases pollen almost year-round and abounds throughout the southern United States, where it’s cultivated for ornamental purposes and as animal feed. Other grasses, such as rye, timothy, blue, and orchard, share allergens in common, so an allergy to pollen from one of these grasses may also indicate sensitivity to allergens from one or more of these other grasses.

Wheezy weeds

Weeds are plants, too. Many people just don’t consider them to be desirable plants. For the sake of allergies, however, when I refer to weeds, I mean the small, wild, annual plants of no agricultural value or decorative interest. The wind-pollinated weeds that release allergenic pollen don’t produce very attractive or conspicuous flowers. The most significant of these wind-pollinated weeds, in terms of allergic triggers, include ragweed, mugwort, Russian thistle, pigweed, sagebrush, and English plantain.

In the United States, from the mid-Atlantic to northern parts of the Midwest, where ragweed is most highly concentrated, pollination usually begins around August 15 and generally lasts through October (and/or until a first frost), depending on climate conditions. Ragweeds are early risers, with most plants releasing pollen between 6 and 11 a.m. Hot and humid weather usually leads to an increased release of pollen.

Although ragweed pollen is most prevalent east of the Mississippi River, you can find related weed pollens, such as those produced by marsh elder and cocklebur, throughout most parts of North America.

Ragweed to starboard, Captain!

Is that seasickness or allergies? Ragweed pollen has such a broad range that it has been detected 400 miles out to sea. So if you’re on the ocean during ragweed season, I suggest taking your medication with you. (Make sure it’s non-drowsy, especially when you’re at the helm.)

Can’t sneeze the forest for the trees

Of the 700 species of trees that are native to North America, only 65 produce pollen that triggers allergic rhinitis. The pollination season for most of these species usually runs from the end of winter or the beginning of spring until early summer.

Pollens from these types of trees have much shorter ranges than the pollens that wind-pollinating grasses and weeds release. As a result, in most cities and towns, weed and grass pollens are far more likely to affect you than tree pollens. However, in the southeastern United States, the spring tree season is a major problem, with high peaks of pollination over a prolonged period of time.

Trees that produce the most allergenic pollen in North America include elms; willows and poplars; birches; beeches, oaks, and chestnuts; maples and box elders; hickories; mountain cedars; and ashes and olives.

Molds

Talk about moldies and oldies: Molds are some of the oldest and most common organisms on the planet, and they’re widespread in most homes. Think of molds as microscopic fungi or mushrooms. You’ve probably encountered various forms of mold at home, from splotches on your shower door to the greenish growth on that tomato you forgot way in the back of your fridge last year (hope your mom doesn’t find out).

As far back as 1726, mold spores were suspected of being a source of respiratory symptoms. Throughout the United States and Canada, mold spores are some of the most common inhalant allergens, outdoors and indoors, and can be significant triggers of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and other respiratory ailments.

Mold counts usually are much higher than pollen counts and usually rise to peak levels during summer months. Outdoor mold spores are present almost year-round unless prolonged snow cover occurs. This mold-spore propensity is in contrast to pollens, which are released by plants, usually only during distinct seasons. However, at any time, mold counts can suddenly and dramatically rise within a short period and then drop down to previous levels just as abruptly. Because molds also thrive indoors, you may be exposed to mold spores continuously throughout the year.

Outdoor molds grow on field crops such as corn, wheat, soybeans, and on decaying organic matter such as compost, hay, piles of leaves, and grass cuttings, and types of foods, including tomatoes, sweet corn, melons, bananas, and mushrooms.

Spreading spores

As is true of grasses, weeds, and trees, only a few forms of molds produce allergens that trigger asthma and allergic rhinitis symptoms. Airborne mold spores occur almost everywhere on the planet except at the North and South poles. So unless you’re a polar bear or a penguin, odds are that you receive some degree of exposure to mold particles, regardless of where you are. These molds include

Cladosporium: These species produce some of the most abundant wind-borne spores in the world and flourish almost everywhere, except in the coldest regions.

Cladosporium: These species produce some of the most abundant wind-borne spores in the world and flourish almost everywhere, except in the coldest regions.

Alternaria: These outdoor molds are among the most prominent causes of allergy symptoms in sensitized people.

Alternaria: These outdoor molds are among the most prominent causes of allergy symptoms in sensitized people.

Aspergillus: A medically important indoor mold, found in agricultural areas, crawl spaces of homes, and even outdoor air throughout North America. A variety of allergic respiratory diseases associated with exposure to aspergillus are recognized, including allergic asthma (see Chapter 5), hypersensitivity pneumonitis (farmer’s lung), and a serious respiratory disease known as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA).

Aspergillus: A medically important indoor mold, found in agricultural areas, crawl spaces of homes, and even outdoor air throughout North America. A variety of allergic respiratory diseases associated with exposure to aspergillus are recognized, including allergic asthma (see Chapter 5), hypersensitivity pneumonitis (farmer’s lung), and a serious respiratory disease known as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA).

Moldy matters

You experience asthma and allergic rhinitis symptoms most of the year, rather than during specific seasons.

You experience asthma and allergic rhinitis symptoms most of the year, rather than during specific seasons.

Your symptoms worsen during summer months, even when pollen allergens aren’t present to any significant degree.

Your symptoms worsen during summer months, even when pollen allergens aren’t present to any significant degree.

Your asthma and/or allergies worsen near croplands, especially around grains and overgrown fields, or during or immediately following gardening.

Your asthma and/or allergies worsen near croplands, especially around grains and overgrown fields, or during or immediately following gardening.

House Dust

House dust may be the most prevalent of all triggers of respiratory symptoms in your life. Recent studies show that the major inhalant allergens found in house dust can be the most important risk factors in triggering asthma attacks.

Common components of house dust include

Dust mite allergens

Dust mite allergens

Animal dander

Animal dander

Insect fragments

Insect fragments

Fibers such as acrylic, rayon, nylon, cotton, and other materials

Fibers such as acrylic, rayon, nylon, cotton, and other materials

Wood and paper particles

Wood and paper particles

Hair and skin flakes

Hair and skin flakes

Tobacco ash

Tobacco ash

Particles of salt, sugar, other spices, and minerals

Particles of salt, sugar, other spices, and minerals

Plant pollen and fungal spores

Plant pollen and fungal spores

Dust mites

The most potent allergen in house dust comes from the house dust mite (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and/or Dermatophagoides farinae, depending on where you live). Check out Figure 10-1 to see a dust mite. These tiny, eight-legged microscopic spider relatives live in house dust where they feed on dead skin flakes that warm-blooded creatures such as humans constantly shed (hence the scientific name dermatophagoides, meaning skin-eater; but don’t worry — dust mites don’t eat living skin) at rates of up to 1.5 grams per day — that’s a lot of dust mite chow.

The fecal matter (or waste, to put it more delicately) that they produce, at the average rate of 20 particles per day, is the most prevalent form of house dust allergens and often causes respiratory problems in humans.

|

Figure 10-1: Dust mites are among the most abundant sources of allergic triggers. |

|

Eighty percent of patients with allergies test positive for sensitivity to the dust mite allergen. Because dust mites usually are as snug as bugs in a rug, people rarely come into direct contact with the live creatures themselves — just with their waste or decomposing bodies, which also can be a significant source of house dust allergens. Dust mites thrive in dark, warm, and humid environments such as mattresses, pillows, box springs, rugs, towels, upholstered furniture, drapes, and stuffed toys.

If you wonder about the seriousness of dust mite infestations, consider this study: Dust mites were stained with a dye and then released on a couch in a home. (The family gave informed consent for the experiment.) By the next day, the dust mites had infested the family car, and some of the creatures also were found on the clothes of family members who sat on the couch. Within ten days, marked dust mites were recovered from every room in the house.

In another experiment, dust mites in an infested rug were killed and the rug was cut into pieces and stored at different combinations of temperature and humidity. Almost two years later, the allergens from the dead mites were as potent as they originally were.

What else is in my house dust?

Dander from household pets is another major trigger of respiratory symptoms. Although you may not have pets of your own, whenever you’re in contact with other pet owners, dander from their animals can get on your hands or clothes, which you then introduce into your home. In addition, the urine from household pests, such as mice and rats, can be significant triggers of asthma symptoms and allergic reactions. Furthermore, recent studies increasingly show that allergens in cockroach debris and waste can contribute to asthma attacks, especially in children.

Dust gets in your eyes . . . or nose, throat, and lungs

You experience asthma and/or allergy symptoms as a result of dusting, making beds, or changing blankets and bed linens.

You experience asthma and/or allergy symptoms as a result of dusting, making beds, or changing blankets and bed linens.

Your symptoms seem to occur year-round rather than seasonally.

Your symptoms seem to occur year-round rather than seasonally.

Your symptoms are worse when you’re indoors.

Your symptoms are worse when you’re indoors.

Your symptoms are worse when you awaken in bed in the morning.

Your symptoms are worse when you awaken in bed in the morning.

Avoidance and Allergy-Proofing

In the first part of this chapter, I tell you about the most important and prevalent triggers of respiratory symptoms that affect most asthma patients. In the rest of the chapter, I discuss various steps you can take to avoid those triggers. Using these methods usually helps you improve your life with asthma.

Avoiding — or at least significantly decreasing your exposure to — substances in your environment that trigger your asthma attacks and allergic reactions often helps relieve your symptoms and thus improves your overall health. These avoidance measures also can reduce the need for medication or shots, thereby saving you much time and money.

Why avoidance matters

You’ve probably heard the joke about the patient who complains, “Doc, it hurts when I do this,” to which the doctor replies, “Then stop doing that.” (For more great doctor jokes, come to one of my book signings.) Silly as that joke seems, the doctor’s advice exemplifies the basic concept of avoidance. Depending on your sensitivity, avoid the substances or levels of exposure to the substances that trigger (that’s why such substances are called triggers ) an allergic reaction.

Avoidance seems simple enough. In real life, however, the trick is figuring out — short of living in a bubble — the practical and effective steps you can take to minimize your contact with allergy triggers.

Developing an avoidance checklist

Environmental control measures are vital components of any allergist’s treatment plan. Every practicing allergist focuses on helping you create and implement an effective avoidance strategy for you, your spouse, your child, or other people with asthma who live with you. The plan that you and your allergist develop will likely include these general steps:

1. Identifying asthma and allergy triggers in your environment, especially indoor allergens and irritants.

2. Recognizing situations in which you may come into contact with those allergy triggers.

3. Discovering how to avoid allergens or minimizing contact with them.

4. Allergy-proofing your home.

Taking time for terminology

Allergen load: Your total level of exposure, at any given time, to any combination of allergens that trigger your allergies.

Allergen load: Your total level of exposure, at any given time, to any combination of allergens that trigger your allergies.

Allergic threshold: Your level of sensitivity to an allergen. A low allergic threshold means that your sensitivity to an allergen is high — even a small exposure to the substance can trigger your symptoms. A high allergic threshold means that your body requires a higher concentration of allergens to trigger symptoms. Your threshold level, however, can decrease when you’re exposed too often to large quantities of an allergen or to a combination of allergens.

Allergic threshold: Your level of sensitivity to an allergen. A low allergic threshold means that your sensitivity to an allergen is high — even a small exposure to the substance can trigger your symptoms. A high allergic threshold means that your body requires a higher concentration of allergens to trigger symptoms. Your threshold level, however, can decrease when you’re exposed too often to large quantities of an allergen or to a combination of allergens.

Allergy trigger: A normally harmless substance, such as pollen, dust, animal dander, insect stings, and certain foods and drugs, that can provoke an abnormal response by your immune system whenever you’re sensitized to that substance. Doctors usually refer to these substances as allergens.

Allergy trigger: A normally harmless substance, such as pollen, dust, animal dander, insect stings, and certain foods and drugs, that can provoke an abnormal response by your immune system whenever you’re sensitized to that substance. Doctors usually refer to these substances as allergens.

Cross-reactivity: Your immune system is an expert at recognizing related allergens in seemingly unrelated sources. Therefore, if you’re exposed to related allergens within a short time, your allergen load can exceed your allergic threshold, thereby triggering allergic reactions and asthma symptoms.

Cross-reactivity: Your immune system is an expert at recognizing related allergens in seemingly unrelated sources. Therefore, if you’re exposed to related allergens within a short time, your allergen load can exceed your allergic threshold, thereby triggering allergic reactions and asthma symptoms.

Desensitization: In the context of avoidance and allergy-proofing, desensitizing describes the active process of removing, shielding, or reducing the sources of allergens in your environment. Your allergist may advise you to desensitize your home, focusing especially on the bedroom of any person with asthma. Desensitization also refers to a form of treatment in which an allergist injects small amounts of an allergen extract under your skin so that your body can discover how not to react to the substance (see Chapter 11).

Desensitization: In the context of avoidance and allergy-proofing, desensitizing describes the active process of removing, shielding, or reducing the sources of allergens in your environment. Your allergist may advise you to desensitize your home, focusing especially on the bedroom of any person with asthma. Desensitization also refers to a form of treatment in which an allergist injects small amounts of an allergen extract under your skin so that your body can discover how not to react to the substance (see Chapter 11).

HEPA: HEPA stands for high efficiency particulate arrester — an air filtration process developed for hospital operating rooms and other locations that require a sterilized environment. HEPA filters absorb and contain 99.97 percent of all particles larger than 0.3 microns (1/300th the width of a human hair). When the unit truly operates at that level, only 3 of 10,000 particles manage to sneak back into the room. Vacuum cleaners and air purifiers with ULPA (see definition later in this list) and HEPA filters are vital tools for desensitizing and allergy-proofing your indoor environment.

HEPA: HEPA stands for high efficiency particulate arrester — an air filtration process developed for hospital operating rooms and other locations that require a sterilized environment. HEPA filters absorb and contain 99.97 percent of all particles larger than 0.3 microns (1/300th the width of a human hair). When the unit truly operates at that level, only 3 of 10,000 particles manage to sneak back into the room. Vacuum cleaners and air purifiers with ULPA (see definition later in this list) and HEPA filters are vital tools for desensitizing and allergy-proofing your indoor environment.

HVAC: Heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems — your home’s lungs. The quality of air that you breathe indoors is largely dependent on the condition of these systems and the air that flows into and out of your environment through them.

HVAC: Heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems — your home’s lungs. The quality of air that you breathe indoors is largely dependent on the condition of these systems and the air that flows into and out of your environment through them.

ULPA: Ultra low penetration air is even more thorough than the HEPA process. This filtration system is designed to absorb and contain 99.99 percent of all particles larger than 0.12 microns.

ULPA: Ultra low penetration air is even more thorough than the HEPA process. This filtration system is designed to absorb and contain 99.99 percent of all particles larger than 0.12 microns.

Knowing your limits

Avoidance measures rarely require the complete elimination of all asthma and allergy triggers and irritants in your environment. In many cases, you may need only to limit your exposure to certain triggers to prevent or alleviate your respiratory symptoms.

Think of your allergic threshold as a cup and the allergy triggers in your environment as liquid pouring into that cup. Overflowing your small cup (low allergic threshold) may require only a small amount of liquid (allergens), thereby triggering an allergic reaction. A larger cup — a higher threshold — can accommodate more liquid without overflowing (without triggering an allergic reaction). Knowing your limit is the key to mastering your threshold.

Another important concept to bear in mind when considering avoidance is imagining a scale balancing your allergic threshold on one side with allergen load on the other. You won’t set off your allergies unless your level of exposure to allergen triggers overloads your allergic threshold. Keep in mind, however, that your scales can tip not only from excessive exposure to a single allergen but also from exposure to small amounts of a variety of allergens.

Crossing the line

Cross-reactivity also is an important factor in causing allergic reactions and asthma symptoms. It can contribute toward overloading your allergic threshold. For example, when you have sensitivity to ragweed, you may also be sensitive to allergens in melons — honeydew, cantaloupe, and watermelon.

This phenomenon occurs because, in some individuals, an allergenic cross-reactivity that exists between certain food proteins and nonfood protein sources can look similar to your immune systems. As a result, in addition to ragweed allergy symptoms during ragweed season, you may also experience itching and swelling of your mouth and lips when eating melons, even though these fruits may not present a problem for you during the rest of the year. Some people also experience cross-reactivity reactions between latex and — of all things — bananas, avocados, papaya, kiwi, and chestnuts.

The Great Indoors

Early on, our human ancestors realized that getting out of the elements and into some type of shelter was a key aspect of surviving the dangers and challenges of the prehistoric world. For the most part, humans have become indoor creatures, progressing from cave and tree dwellings to suburbs, malls, and tightly sealed office buildings. In their dwellings, most people have the means of shielding themselves from the adversities of weather and climate and they’re safe (for the most part) from predators. Safety from their own kind is, of course, another story.

One of the downsides of modern structures is that indoor environments — at home, work, school, and even in cars and other enclosed means of transportation — can often contain far more significant sources of asthma and allergy triggers than outdoor environments. Irritants and allergens can concentrate in most enclosures, and because people spend so much time indoors, that’s where they often experience the most significant exposure to allergy triggers.

Energy-conservation building codes adopted in the United States since the 1970s have worsened the concentration of allergens within structures, because airborne particles that contain allergens and irritants often remain trapped indoors. Although I’m certainly in favor of energy-efficient structures (especially when I see my utility bill), you need to ensure that the air you breathe inside — especially at home — is as safe as possible.

Indoor air pollution: Every breath you take can hurt you

According to the American Lung Association, most people spend 90 percent of their time indoors, spending 60 percent of that time at home. Therefore, indoor air pollution is a serious concern for everyone, particularly because studies show that it can cause or aggravate asthma and allergies.

Allergens on the barbie?

The issue of outdoor and indoor exposure to allergens and irritants is similar to the difference between barbecuing outside or inside. When you cook outside, smoke dissipates. Yes, smoke contributes to overall air pollution, but that’s another story. This backyard barbecue process is similar to the way outdoor air dilutes the effects of pollutants and allergens.

If you’re crazy enough to bring your grill inside, seal all the windows and doors, turn off the ventilation, and then fire up the coals, smoke would fill your house within two minutes. Now, imagine that smoke as indoor allergens and irritants. All too frequently, many people breathe this polluted air in their indoor environments. The allergy-proofing steps I provide in the next section show you how to avoid and control indoor air pollution.

Allergy-Proofing Begins at Home

On average, most people spend a third of their lives in the bedroom — much of that time in bed. As a result, the bedroom is the most important single area of your home. After allergy-proofing your bedroom, try using it as much as possible to ensure that you give your allergies a rest.

In and around your home, the most common and important sources of allergens that you need to focus on when allergy-proofing are

Dust and dust mites

Dust and dust mites

Pets

Pets

Mold

Mold

Pollen

Pollen

Controlling irritants at home also is vital to successful avoidance therapy. Although these substances don’t trigger allergic responses by your body’s immune system (as is the case with allergens), they often worsen existing asthma or allergy conditions.

Aerosols, paints, and smoke from wood-burning stoves

Aerosols, paints, and smoke from wood-burning stoves

Glue

Glue

Household cleaners

Household cleaners

Perfumes and scents

Perfumes and scents

Scented soaps

Scented soaps

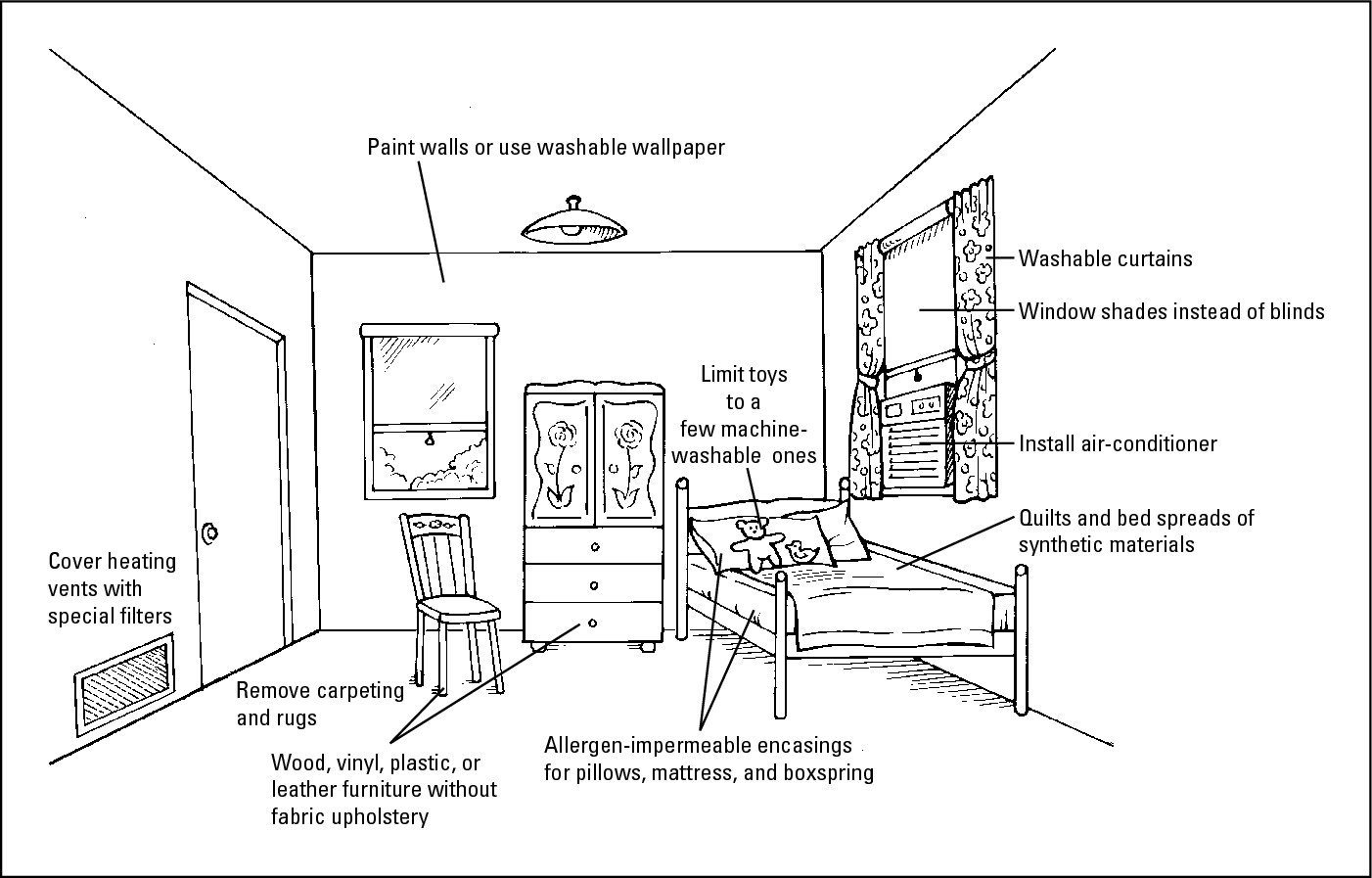

The basics of allergy-proofing are illustrated in Figure 10-2 and explained in more detail in the sections that follow.

|

Figure 10-2: An allergy-proofed bedroom. |

|

Controlling the dust in your house

Studies show that the average six-room home in the United States collects 40 pounds of dust each year. House dust is one of the most prevalent asthma and allergy triggers in any home, and unfortunately, it’s everywhere. Think of house dust as one of life’s inevitabilities — along with death and taxes.

Ridding your house of dust mites

Allergy-proofing your bedroom and home likely involves dealing with dust mites more than with any other allergy trigger, because these microscopic creatures produce the single largest component of house dust that triggers respiratory symptoms in asthma patients. Although you’ve probably never seen them, dust mites are a fact of life — they’re bound to follow almost anyplace you settle.

Controlling dust mites in the bedroom

Few of us ever go to bed alone. Dust mites thrive in dark and humid environments such as mattresses, pillows, and box springs. In fact, the average bed contains 2 million dust mites, which means that you may breathe in significant amounts of dust mite allergens while you sleep. Dust mites also survive well in blankets, carpets, towels, upholstered furniture, drapery, and children’s stuffed toys.

Although eradication of these natural inhabitants of your home is virtually impossible — the females lay 20 to 50 eggs every three weeks — you can take practical and effective steps to minimize exposure to dust mite allergens.

Beds: Encase all pillows, mattresses, and box springs in special allergen-impermeable casings, and mount all beds on bed frames. Wash all bed linens in hot water (at least 130 degrees) every two weeks. Only use pillows, blankets, quilts, and bedspreads made of synthetic materials. Avoid down-filled (feather) comforters and pillows.

Beds: Encase all pillows, mattresses, and box springs in special allergen-impermeable casings, and mount all beds on bed frames. Wash all bed linens in hot water (at least 130 degrees) every two weeks. Only use pillows, blankets, quilts, and bedspreads made of synthetic materials. Avoid down-filled (feather) comforters and pillows.

Temperature and

climate control: Don’t locate your bedroom in a warm (more than 72 degrees), humid area. Likewise, use air conditioners or dehumidifiers to keep the humidity in your home below 50 percent. You may want to use a humidity gauge to monitor humidity levels.

Temperature and

climate control: Don’t locate your bedroom in a warm (more than 72 degrees), humid area. Likewise, use air conditioners or dehumidifiers to keep the humidity in your home below 50 percent. You may want to use a humidity gauge to monitor humidity levels.

Carpets and drapes: Whenever possible, go for the bare look in your home — remove carpeting and thick rugs. Bare surfaces such as hardwood, linoleum, or tile floors are inhospitable to dust mites and are also much easier to clean, thereby minimizing dust buildup. If you can’t remove your carpeting and rugs, treat them with products that deactivate dust mite allergens. I also recommend washable curtains or window shades rather than heavy draperies or blinds.

Carpets and drapes: Whenever possible, go for the bare look in your home — remove carpeting and thick rugs. Bare surfaces such as hardwood, linoleum, or tile floors are inhospitable to dust mites and are also much easier to clean, thereby minimizing dust buildup. If you can’t remove your carpeting and rugs, treat them with products that deactivate dust mite allergens. I also recommend washable curtains or window shades rather than heavy draperies or blinds.

Housekeeping: Vacuum thoroughly, at least once a week, with a HEPA or ULPA vacuum cleaner (see the “Taking time for terminology” section, earlier in this chapter). When you have allergies, wear a dust mask when cleaning or engaging in any activity that stirs up dust, and consider cleaning your furniture with a tannic acid solution.

Housekeeping: Vacuum thoroughly, at least once a week, with a HEPA or ULPA vacuum cleaner (see the “Taking time for terminology” section, earlier in this chapter). When you have allergies, wear a dust mask when cleaning or engaging in any activity that stirs up dust, and consider cleaning your furniture with a tannic acid solution.

Ventilation: Use HEPA air cleaners to keep the indoor air throughout your home as pure as possible. (See the “Taking time for terminology” section, earlier in this chapter.) Cover any heating vents with special vent filters to clean the air before it enters your rooms.

Ventilation: Use HEPA air cleaners to keep the indoor air throughout your home as pure as possible. (See the “Taking time for terminology” section, earlier in this chapter.) Cover any heating vents with special vent filters to clean the air before it enters your rooms.

Decorations and furnishings: Use furniture made of wood, vinyl, plastic, and leather throughout your home rather than furniture made of upholstery. Likewise, make your bedroom as uncluttered and wipeable as possible. Avoid shelves, pennants, posters, photos or pictures, heavy cushions, and other dust collectors. Limit the clothes, books, and other personal objects in your bedroom to the essentials, and make sure that you shut the ones you keep in closets or drawers when not in use.

Decorations and furnishings: Use furniture made of wood, vinyl, plastic, and leather throughout your home rather than furniture made of upholstery. Likewise, make your bedroom as uncluttered and wipeable as possible. Avoid shelves, pennants, posters, photos or pictures, heavy cushions, and other dust collectors. Limit the clothes, books, and other personal objects in your bedroom to the essentials, and make sure that you shut the ones you keep in closets or drawers when not in use.

If your child has allergies or asthma, don’t turn his or her bedroom into a stuffed animal zoo. Instead, try limiting those types of toys to a few machine-washable ones. Keep your child’s stuffed animals and toys in the closet or in a closed chest, container, or drawer when not in use.

Regulating pet dander

Pets are cherished members of many households. However, dander (skin flakes) from these animals is a significant source of allergy triggers for many people. All warm-blooded household pets, regardless of hair length, produce proteins in their dander and saliva that can trigger allergies. Dead skin cells in their dander can even serve as a food supply for dust mites. Cat dander residue can linger at significant exposure levels in carpets for up to 20 weeks and in mattresses for years, even after you remove the animal.

Keeping your pet outdoors whenever possible.

Keeping your pet outdoors whenever possible.

If keeping your pet outdoors isn’t possible, by all means, try to keep the pet out of the patient’s bedroom. Also consider running a HEPA filter 24 hours a day in the bedroom and keeping the door closed.

Making sure that anyone who touches your pet washes his or her hands before contacting the patient or entering the patient’s bedroom.

Making sure that anyone who touches your pet washes his or her hands before contacting the patient or entering the patient’s bedroom.

Washing your pet with water once a week. Doing so may remove surface allergens and possibly reduce the amount of dander that can stick to other household members’ clothes and bodies (thereby reaching the patient’s bedroom). Although it may take some training (and a few scratch marks), even cats can get used to baths.

Washing your pet with water once a week. Doing so may remove surface allergens and possibly reduce the amount of dander that can stick to other household members’ clothes and bodies (thereby reaching the patient’s bedroom). Although it may take some training (and a few scratch marks), even cats can get used to baths.

Controlling mold in your abode

Molds release fungal spores into the air. Theses spores settle on organic matter and grow into new mold clusters. When inhaled by sensitized individuals, these airborne spores can trigger allergic symptoms. Airborne mold spores are more numerous than pollen grains, and unlike pollen, they don’t have a limited season. In many parts of the United States and Canada, mold spores may be present until the first snow cover.

Outdoor mold spores can enter your home through the air, by blowing in open windows and doors, and through vents. Indoor molds can grow year-round, and they thrive in dark, humid areas of the home, such as basements and bathrooms. Molds also grow under carpets and in pillows, mattresses, air conditioners, garbage containers, and refrigerators. The older your home, the larger the amount of mold that grows there.

Avoiding damp areas of your home, such as an unfinished basement or a room with a water leak. Or use a dehumidifier to lower humidity in those areas to 35 percent to 40 percent.

Avoiding damp areas of your home, such as an unfinished basement or a room with a water leak. Or use a dehumidifier to lower humidity in those areas to 35 percent to 40 percent.

Making sure your clothes dryer vents to the outside.

Making sure your clothes dryer vents to the outside.

Ventilating your bathroom well, especially after showers or bathing. Use mold-killing and mold-preventing solutions behind the toilet, around the sink, shower, bathtub, washing machine, and refrigerator, and in other areas of your home where water or moisture collect.

Ventilating your bathroom well, especially after showers or bathing. Use mold-killing and mold-preventing solutions behind the toilet, around the sink, shower, bathtub, washing machine, and refrigerator, and in other areas of your home where water or moisture collect.

Cleaning any visible mold from the walls, floors, and ceiling by using a nonchlorine bleach.

Cleaning any visible mold from the walls, floors, and ceiling by using a nonchlorine bleach.

Taking out the trash and cleaning your garbage container regularly to prevent mold growth.

Taking out the trash and cleaning your garbage container regularly to prevent mold growth.

Drying out damp footwear and clothing in which mold can breed. Don’t hang clothes outside, where they can become landing areas for mold spores.

Drying out damp footwear and clothing in which mold can breed. Don’t hang clothes outside, where they can become landing areas for mold spores.

Limiting the number of indoor plants or removing them altogether, because mold may grow in potting soil. Dried flowers may also contain mold, so avoid them, too.

Limiting the number of indoor plants or removing them altogether, because mold may grow in potting soil. Dried flowers may also contain mold, so avoid them, too.

Pollen-proofing

Allergic rhinitis is perhaps the best-known allergy of all. Many people associate this type of allergy primarily with outdoor exposure to pollen. However, you may also experience significant levels of pollen at home, and these exposures also can trigger allergic rhinitis symptoms.

Most pollens are wind-borne; they often blow indoors (typically through open windows and doors) and trigger allergic symptoms, such as allergic rhinitis, within your home and not just outdoors. Wind-pollinated trees, grasses, and weeds produce pollen during various times of the year. (See the “Counting your pollens” section, earlier in this chapter, for details about pollen counts and contact information for the National Allergy Bureau so that you can obtain its reports on local pollen and mold conditions.)

Avoiding intense outdoor activities, such as exercise or strenuous work, during the early morning and late afternoon hours when pollen counts are highest. Whenever you need to work outside, wear a pollen and dust mask.

Avoiding intense outdoor activities, such as exercise or strenuous work, during the early morning and late afternoon hours when pollen counts are highest. Whenever you need to work outside, wear a pollen and dust mask.

Closing windows and running a HEPA or ULPA air purifier.

Closing windows and running a HEPA or ULPA air purifier.

Cleaning and replacing your air conditioner filters regularly.

Cleaning and replacing your air conditioner filters regularly.

Washing your hair before going to bed to avoid getting pollen on your pillow.

Washing your hair before going to bed to avoid getting pollen on your pillow.

Using a clothes dryer rather than hanging the wash outside where it acts as a filter trap for pollen. You may like the idea of fresh, air-dried laundry, but your target organs (see Chapter 1) won’t enjoy the allergic reactions that all the fresh pollen triggers — especially when you hang sheets and pillowcases out on the line.

Using a clothes dryer rather than hanging the wash outside where it acts as a filter trap for pollen. You may like the idea of fresh, air-dried laundry, but your target organs (see Chapter 1) won’t enjoy the allergic reactions that all the fresh pollen triggers — especially when you hang sheets and pillowcases out on the line.