Chapter 11

Getting Allergy Tested and Allergy Shots

In This Chapter

Using your skin test results

Using your skin test results

Making informed choices about immunotherapy

Making informed choices about immunotherapy

Glancing to see what the future holds

Glancing to see what the future holds

D epending on the severity and nature of your asthma and allergies (such as allergic rhinitis, or hay feverpharmacotherapy

Doctors use skin tests to confirm that your symptoms result from allergies instead of some other cause. Doctors also use skin tests to identify, if possible, the specific allergens that trigger your asthma symptoms and allergic symptoms and reactions. Later in this chapter, I explain the two most common types of allergy skin testing that doctors use.

Meanwhile, immunotherapy is also known as allergy shots, desensitization, hyposensitization, or allergy vaccination. The advisability of this treatment depends on whether skin testing provides clear evidence that you’re allergic to specific allergens, what those allergens are, and how they correlate with your medical history.

This chapter takes a closer look at both of these specialized diagnostic and treatment procedures, so you know what to expect.

Diagnosing with Skin Tests

Allergists consider skin tests the most reliable and precise method for diagnosing allergies.

After completion of the skin tests, you should remain under observation for at least 30 minutes. If the tests produce a positive reaction, your allergist or test administrator examines and measures the resulting wheal and erythema. Clinicians use these measurements to help determine your level of sensitivity to the specific allergen that was administered. If your physician concludes that you need immunotherapy, knowing your level of sensitivity to the allergen often is important in determining a safe starting dosage for your first series of allergy shots.

Pins and needles

Prick-puncture: Sometimes referred to as a scratch test, clinicians perform this test on the surface of your back or on your forearm.

Prick-puncture: Sometimes referred to as a scratch test, clinicians perform this test on the surface of your back or on your forearm.

Intracutaneous: Allergists perform this test, also known as intradermal testing, only when the prick-puncture test fails to produce a significant positive result. The intracutaneous test involves a series of small injections of allergen solution in rows just below the surface of the skin on your arm or forearm.

Intracutaneous: Allergists perform this test, also known as intradermal testing, only when the prick-puncture test fails to produce a significant positive result. The intracutaneous test involves a series of small injections of allergen solution in rows just below the surface of the skin on your arm or forearm.

For both prick-puncture and intracutaneous tests, a positive reaction usually appears within 20 minutes. With either test, you needn’t worry about someone turning you into a pincushion or sticking you with a giant syringe. The intracutaneous test uses only very fine needles just beneath the surface of the skin and, like the prick-puncture test (on the surface of the skin), produces minimal discomfort.

Skin tests and antihistamines: Not a good mix

After carefully reviewing your condition and history, if your doctor advises skin testing, you probably need to discontinue using your antihistamine medications (and other products in certain cases, but usually not your asthma drugs) for several days prior to the test. The presence of these drugs in your body can interfere with the skin test results. However, it’s unlikely that you’ll need to stop most of your other medications.

The following list offers some general guidelines about discontinuing various common products; however, your allergist can provide you with more exact instructions, based on the specific medications that you take.

Discontinue older, sedating, first-generation, over-the-counter (OTC) antihistamines such as Benadryl, Chlor-Trimeton, Dimetapp, Tavist-1, and similar products for 48 to 72 hours before your skin test.

Discontinue older, sedating, first-generation, over-the-counter (OTC) antihistamines such as Benadryl, Chlor-Trimeton, Dimetapp, Tavist-1, and similar products for 48 to 72 hours before your skin test.

You may need to stop using newer, nonsedating, second-generation antihistamines, such as Allegra, Clarinex (and its OTC precursor, Claritin), Zyrtec, or Seldane, for as long as two to four days prior to testing. Likewise, studies show that Hismanal can interfere when taken up to three months prior to having skin tests. Therefore, you and your physician need to plan accordingly whenever you take Hismanal and anticipate taking a skin test. (Seldane and Hismanal no longer are available in the United States but still are sold in Canada and other countries; see Chapter 12.)

You may need to stop using newer, nonsedating, second-generation antihistamines, such as Allegra, Clarinex (and its OTC precursor, Claritin), Zyrtec, or Seldane, for as long as two to four days prior to testing. Likewise, studies show that Hismanal can interfere when taken up to three months prior to having skin tests. Therefore, you and your physician need to plan accordingly whenever you take Hismanal and anticipate taking a skin test. (Seldane and Hismanal no longer are available in the United States but still are sold in Canada and other countries; see Chapter 12.)

Make sure your allergist knows if you’re taking beta-blockers (Inderal, Tenormin) or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (Nardil, Parnate), because special precautions must be taken when administering skin tests to patients who take these drugs. They sometimes can render epinephrine ineffective. Epinephrine is a rescue medication that doctors use for emergency treatment in cases when rare, severe allergic reactions occur following skin testing.

Make sure your allergist knows if you’re taking beta-blockers (Inderal, Tenormin) or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (Nardil, Parnate), because special precautions must be taken when administering skin tests to patients who take these drugs. They sometimes can render epinephrine ineffective. Epinephrine is a rescue medication that doctors use for emergency treatment in cases when rare, severe allergic reactions occur following skin testing.

Because some of them have antihistamine effects, certain antidepressants also can interfere with skin tests. If you’re taking antidepressants, such as trycyclic antidepressants (Elavil or Sinequan), check with the doctor who prescribed them to find out whether you can safely stop taking those products for a brief period or whether substituting another antidepressant (such as Prozac or Paxil) that doesn’t have antihistaminic properties is possible. If discontinuing these drugs to undergo skin testing is permitted, you may need to stop taking them for three to five days prior to your test.

Because some of them have antihistamine effects, certain antidepressants also can interfere with skin tests. If you’re taking antidepressants, such as trycyclic antidepressants (Elavil or Sinequan), check with the doctor who prescribed them to find out whether you can safely stop taking those products for a brief period or whether substituting another antidepressant (such as Prozac or Paxil) that doesn’t have antihistaminic properties is possible. If discontinuing these drugs to undergo skin testing is permitted, you may need to stop taking them for three to five days prior to your test.

Skin conditions such as contact dermatitis, eczema, psoriasis, or lesions (irritations) in the skin test area also can interfere with your test results. Make sure that your doctor knows about any such conditions before you undergo any skin testing.

Skin conditions such as contact dermatitis, eczema, psoriasis, or lesions (irritations) in the skin test area also can interfere with your test results. Make sure that your doctor knows about any such conditions before you undergo any skin testing.

Starting from scratch: Prick-puncture procedures

Allergists consider prick-puncture tests the most convenient and cost effective screening method for detecting specific IgE antibodies , which are produced by your immune system (see Chapter 6 for an extensive discussion about the immune system) in response to a wide variety of inhalant and food allergens.

When performing a prick-puncture test, an allergist or other qualified medical professional first places a drop of a suspected allergen (in solution form) on your back or your forearm. The test administrator then uses a device that pricks, punctures, or scratches the area to see whether the allergen produces a reaction. The device merely scrapes the skin, without drawing blood.

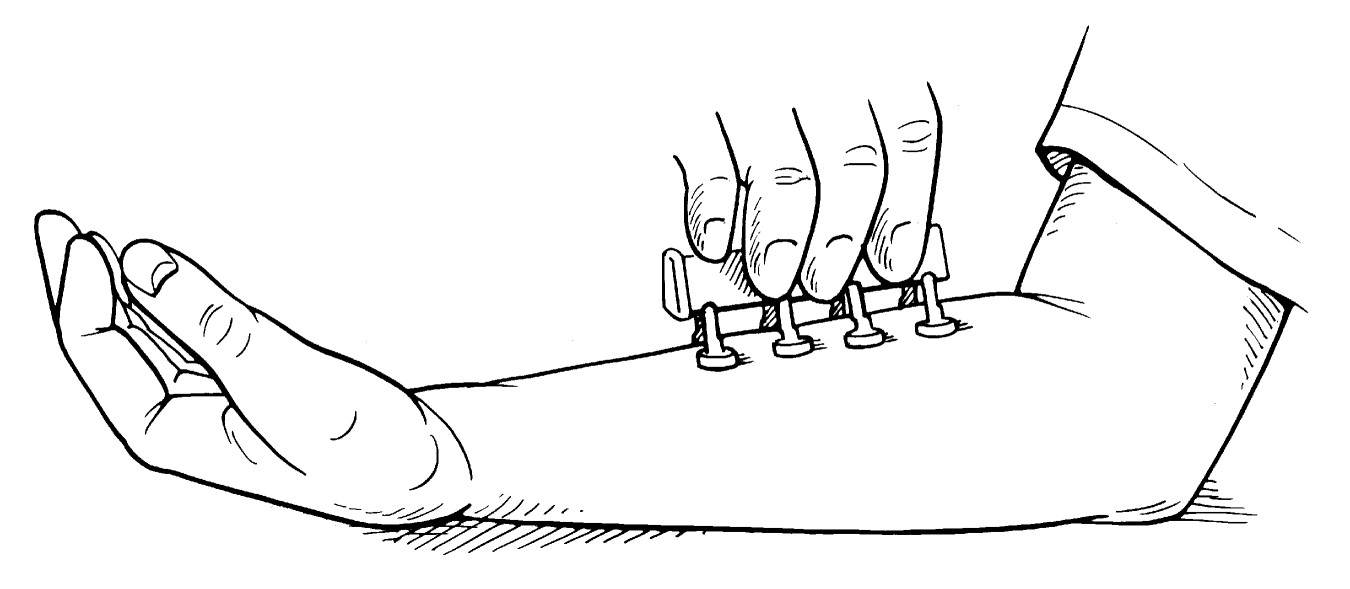

Alternatively, multiple prick-puncture tests can be administered simultaneously with a Multi-Test — a sterile, disposable multiple skin test applicator with eight heads. This procedure uses an applicator that has a specific allergen extract on each of its eight applicator heads and is applied directly to the patient’s skin, as shown in Figure 11-1.

|

Figure 11-1: A multiple skin test applicator can be used to administer prick-puncture skin tests. |

|

You may have to undergo as many as 70 prick-puncture tests to conclusively identify inhalant allergens. The number of tests you receive varies according to factors such as the area where you live, work, or go to school, and the types of allergen exposure that you receive. In many cases, your doctor requires fewer tests.

The number of prick-puncture tests that your doctor may need to administer to determine your specific food allergies varies from 20 to 80. However, only a few selected foods (milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, fish, shellfish, soy, and wheat) account for the vast majority of cases of allergic food reactions. By first taking a detailed medical history, in many cases your doctor may need to perform only a few carefully chosen food allergen skin tests to confirm a likely diagnosis of food hypersensitivity, or food allergy (see Chapter 8).

.jpg)

Getting under your skin: Intracutaneous testing

If your prick-puncture tests are inconclusive, your doctor may need to perform up to 40 intracutaneous tests — rarely that many in the case of suspected food allergies — to produce a significant positive reaction and confirm the diagnosis of an allergy.

.jpg)

Because of a variety of factors, including the types of allergen extracts that your allergist administers, delayed reactions can occur with prick-puncture tests but occur more often following intracutaneous tests. The characteristic signs of these reactions include swollen, reddened, numb bumps at the skin test site.

Delayed reactions can develop three to ten hours after your test and may continue for up to 12 hours thereafter. The bumps usually disappear 24 to 48 hours later. These delayed reactions, which are known as late-phase skin reactions, aren’t a sign of immediate hypersensitivity (which I explain in Chapter 6), and allergists often tell their patients to ignore these late reactions.

Skin test side effects

.jpg)

In very rare cases, death from anaphylaxis, a life-threatening reaction that affects many organs simultaneously, has occurred following a skin test. For that reason, medical facilities where doctors perform skin tests need to have appropriate emergency equipment and drugs on hand in the unlikely event that using these items becomes necessary.

Blood testing for allergies

Although most allergists consider skin tests the gold standard for diagnosing allergies, they may not work for every patient. Your allergist may advise diagnosing your allergic condition with a blood test known as radioallergensorbent testing (RAST) or Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). Your doctor may advise you to have a blood test instead of a skin test for the following reasons:

Your prescribing physician advises you not to discontinue medications such as antihistamines and antidepressants that can interfere with skin test results.

Your prescribing physician advises you not to discontinue medications such as antihistamines and antidepressants that can interfere with skin test results.

You suffer from a severe skin condition such as widespread eczema or psoriasis (over a large part of your body), and your doctor is unable to find a suitable skin site for testing.

You suffer from a severe skin condition such as widespread eczema or psoriasis (over a large part of your body), and your doctor is unable to find a suitable skin site for testing.

If your sensitivity level to suspected allergens is so high that any administration of those allergens may result in potentially serious side effects (for example, a history of life-threatening reactions to the ingestion of peanuts), then avoid allergy skin testing.

If your sensitivity level to suspected allergens is so high that any administration of those allergens may result in potentially serious side effects (for example, a history of life-threatening reactions to the ingestion of peanuts), then avoid allergy skin testing.

When problematic behavioral, physical, or mental conditions prevent you from cooperating with the skin-testing process.

When problematic behavioral, physical, or mental conditions prevent you from cooperating with the skin-testing process.

Because RAST can require only one blood sample to analyze many allergens, this method may seem more convenient than skin testing. However, other than the exceptions I list earlier in this section, most allergists rarely use RAST, because it isn’t as accurate as skin testing and can result in an incomplete profile of your allergies. In addition, RAST is more expensive and time-consuming, because a laboratory must analyze blood samples and report test results, which often takes at least two days. If your results return inconclusive, your allergist must perform the test again and wait for new results. In comparison, skin testing usually provides results on the spot within 15 to 30 minutes.

Reviewing Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy (also known as allergy shots, desensitization, hyposensitization, or allergy vaccination) currently is the most effective form of treating the underlying immunologic mechanism (see Chapter 6) that causes allergic conditions such as allergic rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis, allergic asthma, and allergies to insect stings. However, immunotherapy, at present, doesn’t provide a safe and effective treatment for food allergies.

Seeing how immunotherapy works

Decreasing production of IgE antibodies. IgE antibodies are the agents that bind with allergens at receptor sites on the surfaces of mast cells, thus initiating the release of potent chemical mediators of inflammation such as histamine and leukotrienes. These chemicals trigger allergic reactions and asthma symptoms. (See Chapter 6 for an extensive explanation of the complex immune system responses involved in asthma and allergies, such as allergic rhinitis.)

Decreasing production of IgE antibodies. IgE antibodies are the agents that bind with allergens at receptor sites on the surfaces of mast cells, thus initiating the release of potent chemical mediators of inflammation such as histamine and leukotrienes. These chemicals trigger allergic reactions and asthma symptoms. (See Chapter 6 for an extensive explanation of the complex immune system responses involved in asthma and allergies, such as allergic rhinitis.)

Initiating the production of other allergen-specific IgG antibodies.

Allergen-specific IgG antibodies also are known as blocking antibodies. Immunotherapy can stimulate your body to produce blocking antibodies, which compete with mast-cell bound IgE for antigen, thus preventing the initial sensitization, activation, and subsequent release of potent chemical mediators of inflammation from these cells. To find out more about the cast of Ig (immunoglobulin) antibodies and other characters involved in the complex immune system responses that result in allergy and asthma symptoms, turn to Chapter 6 (especially if you’re a budding immunologist).

Initiating the production of other allergen-specific IgG antibodies.

Allergen-specific IgG antibodies also are known as blocking antibodies. Immunotherapy can stimulate your body to produce blocking antibodies, which compete with mast-cell bound IgE for antigen, thus preventing the initial sensitization, activation, and subsequent release of potent chemical mediators of inflammation from these cells. To find out more about the cast of Ig (immunoglobulin) antibodies and other characters involved in the complex immune system responses that result in allergy and asthma symptoms, turn to Chapter 6 (especially if you’re a budding immunologist).

Stabilizing the actual mast cells (and basophils). Doing so means that even if IgE antibodies and allergens cross-link on the surface of these cells, your potential allergic reaction is usually less severe, because the release of potent chemical mediators of inflammation is reduced. In addition, immunotherapy can result in decreasing the actual number of mast cells (and basophils) in the affected areas. This reduction in activation and numbers of these cells also results in suppressing the inflam-matory late-phase allergic response following allergen exposure (see Chapter 6).

Stabilizing the actual mast cells (and basophils). Doing so means that even if IgE antibodies and allergens cross-link on the surface of these cells, your potential allergic reaction is usually less severe, because the release of potent chemical mediators of inflammation is reduced. In addition, immunotherapy can result in decreasing the actual number of mast cells (and basophils) in the affected areas. This reduction in activation and numbers of these cells also results in suppressing the inflam-matory late-phase allergic response following allergen exposure (see Chapter 6).

Deciding whether immunotherapy makes sense for you

Immunotherapy may be appropriate for treating your allergies and thus can help you manage your asthma more effectively depending on the following factors:

Effectively avoiding allergens that trigger your asthma symptoms and allergic reactions is impractical, or even impossible, because the life you lead inevitably results in allergen exposure.

Effectively avoiding allergens that trigger your asthma symptoms and allergic reactions is impractical, or even impossible, because the life you lead inevitably results in allergen exposure.

Your respiratory symptoms are consistently severe or debilitating.

Your respiratory symptoms are consistently severe or debilitating.

Managing your asthma and/or allergies requires prohibitively expensive courses of medication, which produce side effects that adversely affect your overall health and quality of life. If the health and financial costs of multiple allergy drugs outweigh their benefits, immunotherapy may make more sense for you.

Managing your asthma and/or allergies requires prohibitively expensive courses of medication, which produce side effects that adversely affect your overall health and quality of life. If the health and financial costs of multiple allergy drugs outweigh their benefits, immunotherapy may make more sense for you.

Allergy testing provides conclusive evidence of specific IgE antibodies, thus enabling your allergist to identify the particular allergens that trigger your symptoms.

Allergy testing provides conclusive evidence of specific IgE antibodies, thus enabling your allergist to identify the particular allergens that trigger your symptoms.

You haven’t experienced serious adverse side effects (as a result of skin testing) to the allergens that your doctor will use in your subsequent course of immunotherapy.

You haven’t experienced serious adverse side effects (as a result of skin testing) to the allergens that your doctor will use in your subsequent course of immunotherapy.

You can make the commitment to see the therapy process through. Immunotherapy isn’t a quick fix, and it requires a significant investment of your time.

You can make the commitment to see the therapy process through. Immunotherapy isn’t a quick fix, and it requires a significant investment of your time.

.jpg)

Getting shots

Injections, or shots, are the most effective and reliable method of administering specially prepared, diluted allergen extracts that allergists use when providing immunotherapy treatment. If needles give you nightmares, relax. Allergy shots are much less painful or traumatic than deep intramuscular shots often needed to effectively administer immunizations or certain medications (such as cortisone or penicillin). That’s because doctors usually administer allergy shots with the same type of fine needle they use in intracutaneous testing, thus causing minimal discomfort.

Allergens that doctors commonly use in immunotherapy treatments for allergic asthma, allergic rhinitis, and allergic conjunctivitis include extracts of inhalant allergens from tree, grass, and weed pollens; mold spores; dust mites; and sometimes animal danders.

In preparing your allergen extract (serum or vaccine), your doctor includes only those allergens for which you previously have demonstrated sensitivity in your skin testing. If your skin tests show sensitivity to multiple allergens (you’re sensitive to many grass and weed pollens, for example), your allergist may mix all the different grass extracts into one vial and all the different weed extracts into another vial. Preparing the serum in such combinations ensures that you receive only one shot for each group of extracts, thus reducing the number of injections that you need for effective therapy.

Your allergist may even determine that mixing doses of all your allergens into a single shot on a particular visit is an option for you based on:

Your allergic sensitivity

Your allergic sensitivity

The volume of extract that needs to be administered

The volume of extract that needs to be administered

The types of allergen extracts he uses for your therapy

The types of allergen extracts he uses for your therapy

In some cases, for your comfort, it may be preferable to split the required dose of your allergy shot into two or more separate injections.

Although this treatment can greatly reduce your allergy symptoms, immunotherapy isn’t considered a guaranteed permanent cure for asthma and allergies (see Chapters 1 and 6). You likewise still need to continue practicing avoidance measures while receiving immunotherapy, because doing so can significantly enhance the effectiveness of your treatment.

Whenever you’re considering taking medications — including OTC drugs — for allergies or nonallergic conditions.

Whenever you’re considering taking medications — including OTC drugs — for allergies or nonallergic conditions.

About any changes in your medical condition, even if the changes may not seem directly connected to your allergies.

About any changes in your medical condition, even if the changes may not seem directly connected to your allergies.

Pregnancy, which I mention in the nearby sidebar, is an example of a change in medical condition that you need to report to your allergist.

Your adherence is key for an effective immunotherapy program. Follow and maintain the shot schedule (see the next section) that your allergist prescribes as closely as possible. However, avoid shots under the following circumstances:

.jpg)

Illness: If you run a fever, tell your allergist. Receiving an allergy shot while you’re ill isn’t a good idea because your fever symptoms can make detecting an adverse reaction to the shots difficult.

Illness: If you run a fever, tell your allergist. Receiving an allergy shot while you’re ill isn’t a good idea because your fever symptoms can make detecting an adverse reaction to the shots difficult.

Immunizations: Try to avoid scheduling any immunizations on the same day as your allergy shots because potential adverse effects from the immunization can make a reaction from an allergy shot difficult to identify. If you do get an immunization shot on the day of your scheduled allergy shots, let your allergist know; she may advise you to not get your allergy shots that same day.

Immunizations: Try to avoid scheduling any immunizations on the same day as your allergy shots because potential adverse effects from the immunization can make a reaction from an allergy shot difficult to identify. If you do get an immunization shot on the day of your scheduled allergy shots, let your allergist know; she may advise you to not get your allergy shots that same day.

Shot schedules

The most effective way of administering immunotherapy is by providing perennial therapy, which involves receiving shots of allergen extracts year-round. Studies show that perennial therapy provides the longest and most successful reduction of your level of sensitivity to specific allergens.

Your allergist begins your therapy by administering shots once or twice a week, starting with a very small amount of a diluted dose of allergen extracts.

Your allergist begins your therapy by administering shots once or twice a week, starting with a very small amount of a diluted dose of allergen extracts.

Your allergist gradually increases your allergen dosage by increasing the amount and concentration of the extract week by week until you reach the maintenance dose in about three to six months. The maintenance dose refers to a predetermined amount of maximal concentration or the highest strength that you can tolerate without producing adverse reactions.

Your allergist gradually increases your allergen dosage by increasing the amount and concentration of the extract week by week until you reach the maintenance dose in about three to six months. The maintenance dose refers to a predetermined amount of maximal concentration or the highest strength that you can tolerate without producing adverse reactions.

After reaching your maintenance dose, allergy symptom relief usually begins. When relief starts, you can continue receiving shots at the maintenance dose level. Likewise, your allergist may extend the interval between your shots from one week to as many as four, depending on your response to the treatment and the levels of exposure that you encounter in your environment.

After reaching your maintenance dose, allergy symptom relief usually begins. When relief starts, you can continue receiving shots at the maintenance dose level. Likewise, your allergist may extend the interval between your shots from one week to as many as four, depending on your response to the treatment and the levels of exposure that you encounter in your environment.

Every time you receive your allergy shots, expect to wait at least 20 minutes afterwards in your allergist’s office so that a medical staff member can inspect and evaluate the areas of skin around your shots and monitor you for any early signs of anaphylaxis. Another benefit of staying in your allergist’s office after your shot: In the rare event that you experience a severe reaction, qualified medical personnel can immediately provide emergency assistance.

Pregnancy and immunotherapy

If you become pregnant while receiving immunotherapy, you’ll be glad to know that your allergy shots are safe during pregnancy. In fact, your allergist may advise you to continue receiving immunotherapy, possibly at a reduced dosage, to minimize any risk of reactions to allergy shots and to continue to provide relief from your respiratory symptoms.

If you stop treatment, you can run the risk of experiencing worsening symptoms. This worsening can lead in turn to increased needs for medication that may not be desirable during your pregnancy. However, if you’re already pregnant and are considering whether or not to start a course of immunotherapy, your allergist may advise you to delay beginning this form of treatment until after delivery.

A long-term relationship

For inhalant allergens, an effective immunotherapy program usually requires shots for at least three to five years. In many cases, if your sensitivity to allergens improves during the course of immunotherapy, you can maintain your level of allergy improvement for several years (or even life-long in some cases) after discontinuing the shots.

Considering side effects

.jpg)

Itchiness of the feet, hands, groin area, and underarms

Itchiness of the feet, hands, groin area, and underarms

Large-scale skin reactions, such as hives or flushing

Large-scale skin reactions, such as hives or flushing

Upper and lower respiratory symptoms, such as sneezing, coughing, tightness of the chest, a swollen or itchy throat, itchy eyes, postnasal drip, difficulty swallowing, and a hoarse voice

Upper and lower respiratory symptoms, such as sneezing, coughing, tightness of the chest, a swollen or itchy throat, itchy eyes, postnasal drip, difficulty swallowing, and a hoarse voice

Nausea, diarrhea, and stomach cramps

Nausea, diarrhea, and stomach cramps

Dizziness, fainting, or a severe drop in blood pressure

Dizziness, fainting, or a severe drop in blood pressure

Looking at Future Forms of Immunotherapy

Nasal sprays: Nasal sprays that are under development may provide a less needle-dependent form of administering allergen extracts to patients.

Nasal sprays: Nasal sprays that are under development may provide a less needle-dependent form of administering allergen extracts to patients.

Sublingual-swallow immunotherapy. This form of allergy treatment, known as SLIT, currently is used in some European countries mainly for pollen allergies. The therapy involves holding drops of allergen extract under the tongue for as long as two minutes before swallowing. Although studies show that SLIT can be effective in reducing symptoms of certain pollen-triggered allergic reactions, patients often need to hold as many as 20 drops (1 ml) under their tongues before swallowing, and that can be challenging for some people. And, unlike allergy shots, which usually require a visit to your doctor’s office, SLIT is intended more as a self-administered therapy, meaning patients can take their doses at home. This raises issues of compliance, because patients may not always be able to adhere on their own to the proper way of taking these drops.

Sublingual-swallow immunotherapy. This form of allergy treatment, known as SLIT, currently is used in some European countries mainly for pollen allergies. The therapy involves holding drops of allergen extract under the tongue for as long as two minutes before swallowing. Although studies show that SLIT can be effective in reducing symptoms of certain pollen-triggered allergic reactions, patients often need to hold as many as 20 drops (1 ml) under their tongues before swallowing, and that can be challenging for some people. And, unlike allergy shots, which usually require a visit to your doctor’s office, SLIT is intended more as a self-administered therapy, meaning patients can take their doses at home. This raises issues of compliance, because patients may not always be able to adhere on their own to the proper way of taking these drops.

Solid/tablet forms of SLIT: Researchers currently are developing a solid form of SLIT, which would consist of a disintegrating tablet that gradually dissolves under the tongue and insures that patients consistently receive an exact dose of prescribed allergen extracts.

Solid/tablet forms of SLIT: Researchers currently are developing a solid form of SLIT, which would consist of a disintegrating tablet that gradually dissolves under the tongue and insures that patients consistently receive an exact dose of prescribed allergen extracts.

Anti-IgE antibodies: The agent in this medication named Xolair (recently approved by the FDA) is a high-tech antibody known as recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Researchers designed this drug to bind to the part of the IgE antibody that otherwise would bind with the IgE receptor site on mast cells, thus preventing the activation of these cells and subsequent allergic reaction (see Chapter 6 for more information about the immune system). In my opinion, this drug not only improves asthma and allergic rhinitis treatment but may also include the potential to block many types of allergic reactions that science hasn’t had much success in controlling adequately — for example, severe allergic food reactions.

Anti-IgE antibodies: The agent in this medication named Xolair (recently approved by the FDA) is a high-tech antibody known as recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Researchers designed this drug to bind to the part of the IgE antibody that otherwise would bind with the IgE receptor site on mast cells, thus preventing the activation of these cells and subsequent allergic reaction (see Chapter 6 for more information about the immune system). In my opinion, this drug not only improves asthma and allergic rhinitis treatment but may also include the potential to block many types of allergic reactions that science hasn’t had much success in controlling adequately — for example, severe allergic food reactions.