Chapter 14

Knowing Asthma Medications

In This Chapter

Adhering to your asthma medication program

Adhering to your asthma medication program

Knowing the difference between preventive and rescue drugs

Knowing the difference between preventive and rescue drugs

Using and maintaining inhalers, holding chambers, holders, and nebulizers

Using and maintaining inhalers, holding chambers, holders, and nebulizers

T reatment with medications, which doctors refer to as pharmacotherapy,

Given the choice, most people would rather not take medications on a regular basis. After all, you have places to go, people to meet, things to do. Remembering to inhale, swallow, or receive an injection of a prescribed medication at the right time in the proper manner can every now and then seem like a nuisance.

Physicians who care for people with asthma are very aware that patients prefer not to take medications on a regular basis. However, asthma is more than the coughing, wheezing, or other symptoms that you may occasionally experience. If you have persistent asthma — like the majority of asthmatics in the United States — some degree of airway inflammation and hyperreactivity (increased sensitivity) is always present, even when you aren’t noticing any obvious respiratory symptoms and therefore feel fine. Controlling that inflammation is the key to keeping your condition from getting out of hand.

As I explain in this chapter, for the vast majority of asthma patients, treatment with at least some form of controller (long-term) and/or rescue (short-term) medication is almost always an essential component of reducing the severity and frequency of your symptoms, and in some cases even eliminating them and improving your overall quality of life.

Understanding the medicine that you take

An informed patient is a healthier person. In fact, making sure that you understand all aspects of your treatment is your responsibility as a patient. Don’t hesitate to inquire about medications your doctor prescribes for your asthma (or any ailment, for that matter). I advise knowing the following information about your prescription before you leave your doctor’s office and begin using a medication:

The name of the medication, the prescribed dose, how often you should take it, and over what period of time you must use it. Your doctor may provide an instruction card with this information. This card can greatly assist you in communicating with other doctors about the medications you’re taking, and it may prove vital in an emergency situation. Likewise, ensuring that the product’s name is clearly written is important, because the drug and brand names of many medications sound alike.

The name of the medication, the prescribed dose, how often you should take it, and over what period of time you must use it. Your doctor may provide an instruction card with this information. This card can greatly assist you in communicating with other doctors about the medications you’re taking, and it may prove vital in an emergency situation. Likewise, ensuring that the product’s name is clearly written is important, because the drug and brand names of many medications sound alike.

The way the drug works, any potential adverse side effects that may result, and what you should do if any of these side effects occur.

The way the drug works, any potential adverse side effects that may result, and what you should do if any of these side effects occur.

What you should do if you accidentally miss a dose or take an extra dose of the medication.

What you should do if you accidentally miss a dose or take an extra dose of the medication.

Any cautions about potential interactions between your prescription and other medications you already take or may take, including over-the-counter (OTC) antihistamines, decongestants, pain relievers, vitamins, or nutritional supplements.

Any cautions about potential interactions between your prescription and other medications you already take or may take, including over-the-counter (OTC) antihistamines, decongestants, pain relievers, vitamins, or nutritional supplements.

Any effects your prescription may have on various aspects of your life, such as your job, school, exercise or sports, other activities, sleeping patterns, and diet.

Any effects your prescription may have on various aspects of your life, such as your job, school, exercise or sports, other activities, sleeping patterns, and diet.

If the medication is for your child, make sure that you know how your child’s dosage may differ from an adult’s.

If the medication is for your child, make sure that you know how your child’s dosage may differ from an adult’s.

If you’re pregnant or nursing a child, make sure that you inform your doctor about these situations.

If you’re pregnant or nursing a child, make sure that you inform your doctor about these situations.

Be sure your doctor knows about any adverse reactions you’ve had to any drugs in the past, including both prescription and OTC preparations.

Be sure your doctor knows about any adverse reactions you’ve had to any drugs in the past, including both prescription and OTC preparations.

Use only those products that are clearly identified to treat the symptoms you experience. Carefully read the product instructions and only take the medication according to your doctor’s directions.

Occasionally, doctors need to prescribe medications off label (beyond the manufacturer’s official recommendations) in order to achieve maximum improvement in a particular patient’s condition. A patient’s health and well-being is a doctor’s primary commitment, and sometimes treatments need to be individualized, such as using high-dose inhaled corticosteroids in cases of severe persistent asthma.

In addition to the printed information that doctors may provide concerning the drugs they prescribe, you can also request materials from the National Council on Patient Information and Education, 4915 Saint Elmo Ave., Suite 505, Bethesda, MD 20814-6082; tel: 301-656-8565, fax: 301-656-4464; e-mail: ncpie@ncpie.info; Web site: www.talkaboutrx.org.

Taking Your Medicine: Why It’s Essential

Looking at asthma’s changing dynamics

Because asthma is a chronic disease, the vast majority of asthmatics need to take appropriate long-acting, preventive (“controller”) medications throughout their lifetime in order to control the underlying airway inflammation that characterizes this disease.

However, asthma is also a dynamic condition. As a result, the combination — and dosages — of medications that your doctor prescribes for you may vary over time. For this reason, consistently consulting your physician about your medication regimen is vital — regardless of whether or not you’re experiencing noticeable respiratory symptoms, instead of deciding on your own whether or not to take a particular medication.

In some cases, your physician may need to step up your medication to obtain better control of your symptoms, while in other instances, your doctor may recommend stepping down your level of medication if you’ve been able to consistently achieve good control of your symptoms. (See Chapter 4 for details on the stepwise approach to asthma management.)

Tracking your asthma condition

In addition, because the frequency and character of your symptoms are liable to change throughout your lifetime, your doctor needs to assess your condition on a regular basis, through lung-function tests (usually with spirometry), as well as by evaluating your peak expiratory flow rate, or PEFR (see Chapter 4). This enables your physician to determine whether your current treatment plan is optimal for your current condition, or if it requires adjustment.

Your asthma condition and severity level may also require adjustment due to factors such as:

Seasonal changes, especially those that involve sudden variations in climate and weather, as well as increases or decreases in pollen and mold counts.

Seasonal changes, especially those that involve sudden variations in climate and weather, as well as increases or decreases in pollen and mold counts.

Moving to a new building, neighborhood, city, and/or region, which can result in exposure to different types and levels of allergens and irritants.

Moving to a new building, neighborhood, city, and/or region, which can result in exposure to different types and levels of allergens and irritants.

Occupational changes, which may also expose you to different types and levels of allergens and irritants.

Occupational changes, which may also expose you to different types and levels of allergens and irritants.

Change in exercise and activity patterns.

Change in exercise and activity patterns.

Change in medical condition, especially if it requires the use of a medication not previously used that has the potential to cause an adverse drug interaction.

Change in medical condition, especially if it requires the use of a medication not previously used that has the potential to cause an adverse drug interaction.

Consult with your physician about any other prescription or OTC medications you may be already taking or may think of taking for other medical conditions, even for relief of minor aches and pains. In some cases, adverse drug interactions can occur between these products and your prescribed asthma medications.

Regular medical visits also enable your doctor to evaluate your inhaler/ nebulizer technique (see “Delivering Your Dose: Inhalers and Nebulizers,” later in this chapter). Your doctor will want to make sure that you are able to derive the maximum benefit from the medication administered by your delivery device.

Preventing and controlling your asthma symptoms

Preventing and controlling your asthma symptoms

Reducing the frequency and severity of your asthma episodes

Reducing the frequency and severity of your asthma episodes

Reversing your airway obstruction and maintaining improved lung function

Reversing your airway obstruction and maintaining improved lung function

In this chapter, I explain and discuss the types of medications that doctors prescribe and recommend to treat asthma, and I also show the proper ways of using different delivery systems designed to administer many of these products.

You can find more detailed information on the specific active ingredients and brand names of individual asthma drugs in the two chapters that follow this one. In Chapter 15, I get in-depth with long-term (controller) drugs, while Chap- ter 16 focuses on quick-relief (rescue) products.

Getting the Long and Short of Asthma Medications

Long-term control medications: Doctors prescribe these products as part of a regular, preventive regimen (most often with daily doses) to achieve and control the underlying airway inflammation that characterizes asthma. For this reason, many of the products in this class are sometimes referred to as anti-inflammatory drugs or controlling drugs.

Long-term control medications: Doctors prescribe these products as part of a regular, preventive regimen (most often with daily doses) to achieve and control the underlying airway inflammation that characterizes asthma. For this reason, many of the products in this class are sometimes referred to as anti-inflammatory drugs or controlling drugs.

Quick-relief medications: At times, you may need these products — often called rescue drugs or relieving drugs — to provide prompt relief of severe and sudden airway constriction and airflow obstruction that can occur when your asthma symptoms unexpectedly worsen.

Quick-relief medications: At times, you may need these products — often called rescue drugs or relieving drugs — to provide prompt relief of severe and sudden airway constriction and airflow obstruction that can occur when your asthma symptoms unexpectedly worsen.

Your doctor may prescribe products from both classes of medications as part of your long-term asthma management program. The specific combination that your doctor prescribes depends on your asthma’s severity and other factors, such as:

Your age. Doses and products for infants, toddlers, children under 12, and the elderly often vary from those doses and products that doctors prescribe for children over 12 and adults. See Chapter 18 for more infor-mation about asthma and children and Chapter 20 for details about asthma and the elderly.

Your age. Doses and products for infants, toddlers, children under 12, and the elderly often vary from those doses and products that doctors prescribe for children over 12 and adults. See Chapter 18 for more infor-mation about asthma and children and Chapter 20 for details about asthma and the elderly.

Your medical history and physical condition. For example, your doctor may adjust dosages and/or products if you’re pregnant or nursing (as I explain in greater detail in Chapter 19).

Your medical history and physical condition. For example, your doctor may adjust dosages and/or products if you’re pregnant or nursing (as I explain in greater detail in Chapter 19).

Any other ailments that may affect you, as well as other medications you may take to treat those conditions. Letting your doctor know about any and all medications you may be using (including OTC ones for minor aches and pains, as well as vitamin supplements and herbal remedies) is essential in order to avoid potential adverse interactions between those products and the asthma medications your doctor may prescribe.

Any other ailments that may affect you, as well as other medications you may take to treat those conditions. Letting your doctor know about any and all medications you may be using (including OTC ones for minor aches and pains, as well as vitamin supplements and herbal remedies) is essential in order to avoid potential adverse interactions between those products and the asthma medications your doctor may prescribe.

Any sensitivities you may have to particular drugs or to certain ingredients in the formulations of particular medications. Some patients may experience tremors or jitteriness when using an older bronchodilator, such as albuterol (Proventil, Ventolin). However, these patients may experience fewer adverse side effects from a newer, improved broncholdilating formulation, such as levalbuterol (Xopenex) and will therefore be more likely to adhere to their asthma medication regimen.

Any sensitivities you may have to particular drugs or to certain ingredients in the formulations of particular medications. Some patients may experience tremors or jitteriness when using an older bronchodilator, such as albuterol (Proventil, Ventolin). However, these patients may experience fewer adverse side effects from a newer, improved broncholdilating formulation, such as levalbuterol (Xopenex) and will therefore be more likely to adhere to their asthma medication regimen.

Toning your lungs, not your muscles

The attempts by some athletes to build up muscle mass by abusing anabolic steroids (related to testosterone) have led many people to harbor negative perceptions about all steroids. Understanding that corticosteroids rarely, if ever, cause the adverse side effects often associated with inappropriate use of anabolic steroids is vital.

In fact, the corticosteroids in the inhaled and oral corticosteroid products often prescribed for asthma patients are a completely different type of drug than anabolic steroids, which are actually synthetic male hormones. The confusion is largely due to the common use of the term steroid, which really is a general term for any of the hormones with related chemical structures produced by specific glands in the body. These hormones include testosterone from the testes, estrogen from the ovaries, and corticosteroids (related to cortisone) from the cortex (outer layer) of the adrenal gland (glands above the kidneys).

Most medical professionals, including myself, consider corticosteroid the proper term — rather than steroid — for the types of inhaled and oral products that I describe in this chapter.

Controlling asthma with long-term medications

If used in an appropriate, consistent manner, long-term control medications can reduce existing airway inflammation and may also help prevent further inflammation. However, your doctor should make sure you understand that these types of drugs aren’t advisable for rescue relief of a severe asthma episode. For this reason, your asthma management plan should also include a prescribed quick-relief medication (most often a quick-relief bronchodilator, as I explain in “Relieving asthma episodes with quick-relief products,” later in this chapter).

Anti-inflammatory drugs, such as inhaled corticosteroids (beclomethasone, budesonide, ciclesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone, mometasone, triamcinolone), oral corticosteroids (methylprednisolone, prednisolone, prednisone), and inhaled mast cell stabilizers (cromolyn and nedocromil). These drugs are available in metered-dose inhaler (MDI), dry-powder inhaler (DPI), or compressor-driven nebulizer (CDN) formulations (see “Delivering Your Dose: Inhalers and Nebulizers,” later in this chapter).

Anti-inflammatory drugs, such as inhaled corticosteroids (beclomethasone, budesonide, ciclesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone, mometasone, triamcinolone), oral corticosteroids (methylprednisolone, prednisolone, prednisone), and inhaled mast cell stabilizers (cromolyn and nedocromil). These drugs are available in metered-dose inhaler (MDI), dry-powder inhaler (DPI), or compressor-driven nebulizer (CDN) formulations (see “Delivering Your Dose: Inhalers and Nebulizers,” later in this chapter).

Long-acting bronchodilators, such as inhaled salmeterol, formoterol, and oral forms of albuterol. Although most long-acting bronchodilators require at least 10 to 30 minutes to begin providing relief and four to six hours to reach full effect, a newer DPI formulation of formoterol (Foradil), approved by the FDA in 2001, starts working in most patients within one to three minutes.

Long-acting bronchodilators, such as inhaled salmeterol, formoterol, and oral forms of albuterol. Although most long-acting bronchodilators require at least 10 to 30 minutes to begin providing relief and four to six hours to reach full effect, a newer DPI formulation of formoterol (Foradil), approved by the FDA in 2001, starts working in most patients within one to three minutes.

A combination of the inhaled corticosteroid fluticasone with the long-acting bronchodilator salmeterol, approved by the FDA in 2000. This product, available under the brand name Advair Diskus, treats both airway constriction and inflammation and is one of the most commonly prescribed asthma medications in the United States.

A combination of the inhaled corticosteroid fluticasone with the long-acting bronchodilator salmeterol, approved by the FDA in 2000. This product, available under the brand name Advair Diskus, treats both airway constriction and inflammation and is one of the most commonly prescribed asthma medications in the United States.

Sustained release methylxanthine bronchodilators, such as oral theophylline.

Sustained release methylxanthine bronchodilators, such as oral theophylline.

Leukotriene modifiers, such as oral montelukast, zafirlukast, and zileuton, available as tablets. If your physician decides that this category of drugs is suitable for your condition, you may benefit from the ease and convenience of taking tablets, which may help you more effectively adhere to the pharmacotherapy aspect of your asthma management plan. (The FDA has also approved montelukast in pediatric formulations as chewable tablets and oral granules for young children and babies.)

Leukotriene modifiers, such as oral montelukast, zafirlukast, and zileuton, available as tablets. If your physician decides that this category of drugs is suitable for your condition, you may benefit from the ease and convenience of taking tablets, which may help you more effectively adhere to the pharmacotherapy aspect of your asthma management plan. (The FDA has also approved montelukast in pediatric formulations as chewable tablets and oral granules for young children and babies.)

Anti-IgE antibodies, which represent an exciting new development in asthma treatment, as I explain in Chapter 17. Omalizumab/rhuMAb-E25 (Xolair), which physicians administer by injection, is the first drug in this class to be approved by the FDA. (See Chapter 6 for a detailed discussion of IgE antibodies and the immune system.)

Anti-IgE antibodies, which represent an exciting new development in asthma treatment, as I explain in Chapter 17. Omalizumab/rhuMAb-E25 (Xolair), which physicians administer by injection, is the first drug in this class to be approved by the FDA. (See Chapter 6 for a detailed discussion of IgE antibodies and the immune system.)

Relieving asthma episodes with quick-relief products

The primary function of quick-relief drugs, also known as rescue medications, is to promptly reverse acute airflow obstruction and relieve constricted airways during an asthma episode. Your doctor may also prescribe a quick-relief product, such as an inhaled beta 2 -adrenergic bronchodilator, prior to exercise to prevent symptoms of exercise-induced asthma, or EIA.

Short-acting beta

2

-adrenergic bronchodilators. These adrenaline-like drugs work by rapidly relaxing the smooth muscles in your airways, causing your airways to open, usually within five minutes of inhaling the medication. Inhaled or aerosol forms of these drugs provide the most effective, prompt relief of acute bronchospasms, and many doctors consider beta

2

-adrenergic bronchodilators the medication of choice for treating asthma symptoms that suddenly worsen and for preventing EIA.

Short-acting beta

2

-adrenergic bronchodilators. These adrenaline-like drugs work by rapidly relaxing the smooth muscles in your airways, causing your airways to open, usually within five minutes of inhaling the medication. Inhaled or aerosol forms of these drugs provide the most effective, prompt relief of acute bronchospasms, and many doctors consider beta

2

-adrenergic bronchodilators the medication of choice for treating asthma symptoms that suddenly worsen and for preventing EIA.

Drugs in this class include albuterol (Proventil, Ventolin), bitolterol (Tornalate), metaproterenol (Alupent), pirbuterol (Maxair), and terbutaline (Brethaire, Brethine, Bricanyl). A recently approved new version (single isomer) of albuterol known as levalbuterol (Xopenex), a short-acting beta 2 -adrenergic bronchodilator, is available in nebulizer (CDN) formulations for patients 6 and older.

Anticholinergics, which may provide added relief when combined with inhaled short-acting beta

2

-adrenergic bronchodilators. These drugs block acetylcholine (a neurotransmitter that stimulates mucus production) and therefore help reduce mucus in your airways. These drugs also relax the smooth muscle around the lungs’ large and medium airways.

Anticholinergics, which may provide added relief when combined with inhaled short-acting beta

2

-adrenergic bronchodilators. These drugs block acetylcholine (a neurotransmitter that stimulates mucus production) and therefore help reduce mucus in your airways. These drugs also relax the smooth muscle around the lungs’ large and medium airways.

Ipratropium bromide (Atrovent) is the most widely used anticholinergic in the United States and is usually prescribed in combination with short-acting beta 2 -adrenergic bronchodilators to dilate your airways.

Oral corticosteroids, also referred to as systemic corticosteroids. Doctors prescribe these for use in asthma attacks in addition to their use as long-acting medications. During moderate-to-severe asthma episodes, your doctor may use oral corticosteroids to rapidly gain control over worsening symptoms. In such cases, oral corticosteroids can help your other quick-relief medications work more effectively, resulting in a more rapid reversal or reduction of airway inflammation, speeding recovery, and reducing the rate of relapse.

Oral corticosteroids, also referred to as systemic corticosteroids. Doctors prescribe these for use in asthma attacks in addition to their use as long-acting medications. During moderate-to-severe asthma episodes, your doctor may use oral corticosteroids to rapidly gain control over worsening symptoms. In such cases, oral corticosteroids can help your other quick-relief medications work more effectively, resulting in a more rapid reversal or reduction of airway inflammation, speeding recovery, and reducing the rate of relapse.

.jpg)

Because prolonged use of oral corticosteroids can lead to adverse systemic side effects, doctors typically prescribe these drugs only as a last resort, and discontinue them (by gradual tapering) as soon as symptoms are under control.

Because prolonged use of oral corticosteroids can lead to adverse systemic side effects, doctors typically prescribe these drugs only as a last resort, and discontinue them (by gradual tapering) as soon as symptoms are under control.

Taking asthma medications prior to surgery

.jpg)

Your doctor may prescribe a short course of oral corticosteroids to improve your lung function starting just prior to surgery. If you’ve taken oral cortico-steroids within the six months prior to surgery, your doctor may also prescribe intravenous hydrocortisone on a set schedule during surgery, with a rapid taper of the dose within 24 hours after your procedure.

Protecting your airways and the ozone at the same time

You’re probably familiar with the issue of replacing ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) with less damaging propellants in refrigerators, air-conditioning systems, and aerosol sprays, particularly in hair, deodorant, and fragrance products. This issue especially affects people with asthma because many metered-dose inhaler (MDI) formulations use CFCs as propellants. A temporary medical exemption allows pharmaceutical companies to continue using CFCs. This exemption is presently scheduled for phase-out by 2005, but it may be extended.

As a result, pharmaceutical companies continue to develop more environmentally friendly propellants for MDI products. Hydrofluoro-alkane (HFA), a new nonchlorinated propel- lant, recently won FDA approval for use in inhaled medications. Proventil HFA, Ventolin HFA (albuterol), and QVAR-HFA (beclomethasone) are the first ozone-friendly products on the market with this propellant, which delivers medication to the lungs more effectively than the CFC propellants developed in the 1950s.

In most cases, because of a lower velocity propellant spray and smaller particle size, a non-CFC propelled product allows more of the medication to get into the smaller, more peripheral airways of your lungs.

Delivering Your Dose: Inhalers and Nebulizers

Understanding how to use inhalers and nebulizers is an important aspect of effectively treating your asthma. If your medication doesn’t go where it’s supposed to go, you don’t benefit from it. One of the unique aspects of treating a respiratory condition is that the proper use of an inhaler is just as important as the medication itself in the inhaler: The objective is to get the medication to the area of your lungs where it can work most effectively.

You can more effectively administer higher concentrations of medication into your airways.

You can more effectively administer higher concentrations of medication into your airways.

You can reduce the risk of systemic side effects that may occur when you use oral forms of these medications.

You can reduce the risk of systemic side effects that may occur when you use oral forms of these medications.

You receive relief from inhaled drugs faster than with oral products.

You receive relief from inhaled drugs faster than with oral products.

Using a metered-dose inhaler

Taking your metered dose correctly

When prescribing your inhaled medication, your physician should instruct you on how to properly use an MDI. Likewise, she should review your inhaler technique at subsequent office visits. The following are some important instructions that apply to using most MDI products.

1. Remove the cap and hold the encased inhaler upright.

2. Shake the inhaler.

3. Tilt your head back slightly and breathe out slowly.

4. Depending on your physician’s specific instructions, open your mouth with your head 1 to 2 inches away from the inhaler or position the inhaler in your mouth.

5. Press down on the inhaler to release medication as you start inhaling or within the first second of inhaling; continue inhaling as you press down on your inhaler.

Breathe in slowly through your mouth, not your nose, for three to five seconds. Press your inhaler only once while you’re inhaling (one breath for each puff). Make sure you breathe evenly and deeply.

6. Hold your breath for ten seconds to allow the medicine to reach deep into your lungs.

7. Repeat puffs as your prescription dictates.

Waiting one minute between puffs may permit the second puff to reach into the airways of your lungs better.

Getting the right dose from your MDI

Loss of prime: People who use inhalers often keep several around the house or office so that backup medication is always handy. Keeping too many back-up inhalers around can lead to infrequent inhaler activation and loss of prime. Loss of prime occurs when the inhaler’s propellant evaporates or escapes from the metering chamber after days or weeks of nonuse. If you haven’t used an inhaler recently, waste a puff of medication (often less than a full dose) into the air before inhaling your first dose to ensure that you receive the full potency of your medication.

Loss of prime: People who use inhalers often keep several around the house or office so that backup medication is always handy. Keeping too many back-up inhalers around can lead to infrequent inhaler activation and loss of prime. Loss of prime occurs when the inhaler’s propellant evaporates or escapes from the metering chamber after days or weeks of nonuse. If you haven’t used an inhaler recently, waste a puff of medication (often less than a full dose) into the air before inhaling your first dose to ensure that you receive the full potency of your medication.

Tail-off: In a misguided attempt to economize, many inhaler users try to squeeze every last drop of medication from their MDIs. However, research indicates that this practice may actually contribute to the documented rise in asthma deaths and poor quality of life for some people with asthma because of a phenomenon known as tail-off. As an MDI reaches its empty stage, dose reliability becomes increasingly unpredictable. Therefore, don’t use your MDI beyond the labeled number of doses, even if you think that some medication remains.

Tail-off: In a misguided attempt to economize, many inhaler users try to squeeze every last drop of medication from their MDIs. However, research indicates that this practice may actually contribute to the documented rise in asthma deaths and poor quality of life for some people with asthma because of a phenomenon known as tail-off. As an MDI reaches its empty stage, dose reliability becomes increasingly unpredictable. Therefore, don’t use your MDI beyond the labeled number of doses, even if you think that some medication remains.

Using new, improved MDIs versus generic brands

Many patients have found that the recently developed Maxair Autohaler, which is formulated to deliver pirbuterol (a short-acting beta 2 -adrenergic bronchodilator), is a simpler, user-friendly way of delivering medication to the airways compared to many other MDIs. That’s mainly because the Autohaler is the only breath-activated MDI approved by the FDA, and requires less coordination to use. The Autohaler also doesn’t require the use of a holding chamber, or spacer (see the section “Using holding chambers,” in this chapter).

Given the more sophisticated design and effectiveness of the Autohaler and of various dry-powder inhalers as well as the recently approved Advair Diskus (which I discuss later in this section), you may wonder why generic MDIs continue to be prescribed.

Using holding chambers

Use a holding chamber when taking inhaled corticosteroids with an MDI to minimize the possibility of developing an oral yeast infection and to improve delivery of the medication to your lungs.

Using a dry-powder inhaler

Budesonide, an inhaled corticosteroid, distributed in the United States as Pulmicort Turbuhaler

Budesonide, an inhaled corticosteroid, distributed in the United States as Pulmicort Turbuhaler

Fluticasone, also an inhaled corticosteroid, available as Flovent Rotadisk to be used with the Diskhaler device

Fluticasone, also an inhaled corticosteroid, available as Flovent Rotadisk to be used with the Diskhaler device

Salmeterol, a long-acting bronchodilator, marketed as Serevent Diskus

Salmeterol, a long-acting bronchodilator, marketed as Serevent Diskus

Fluticasone and salmeterol in combination, marketed as Advair Diskus

Fluticasone and salmeterol in combination, marketed as Advair Diskus

DPIs are easy to use and very effective, if you operate them properly. The medication particles in the dry powder are so small that they can easily reach the tiniest airways. Keep in mind that, unlike most MDIs with a few types of DPIs, you may not taste or feel the medication when using the device. If you’ve administered the medication properly, however, you will receive its benefit.

|

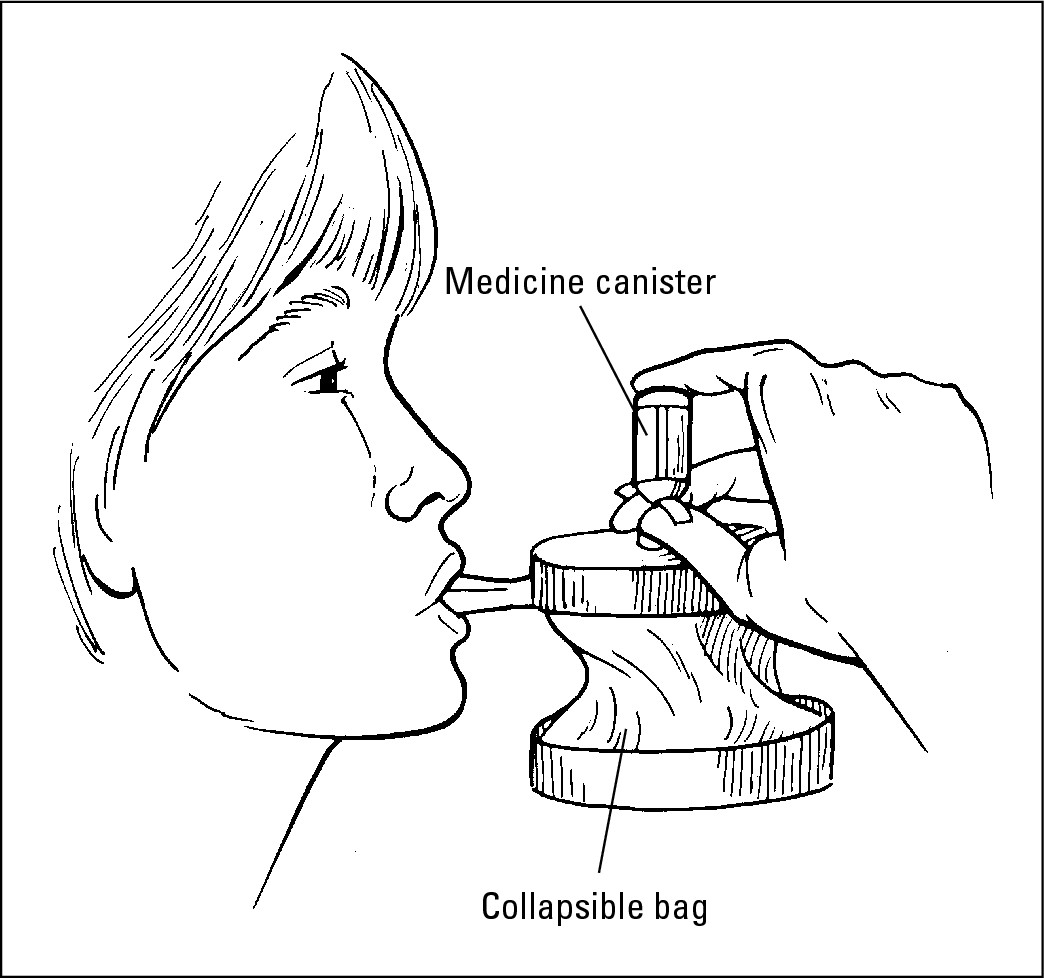

Figure 14-1: An adult using an MDI with a holding chamber and mouthpiece. |

|

|

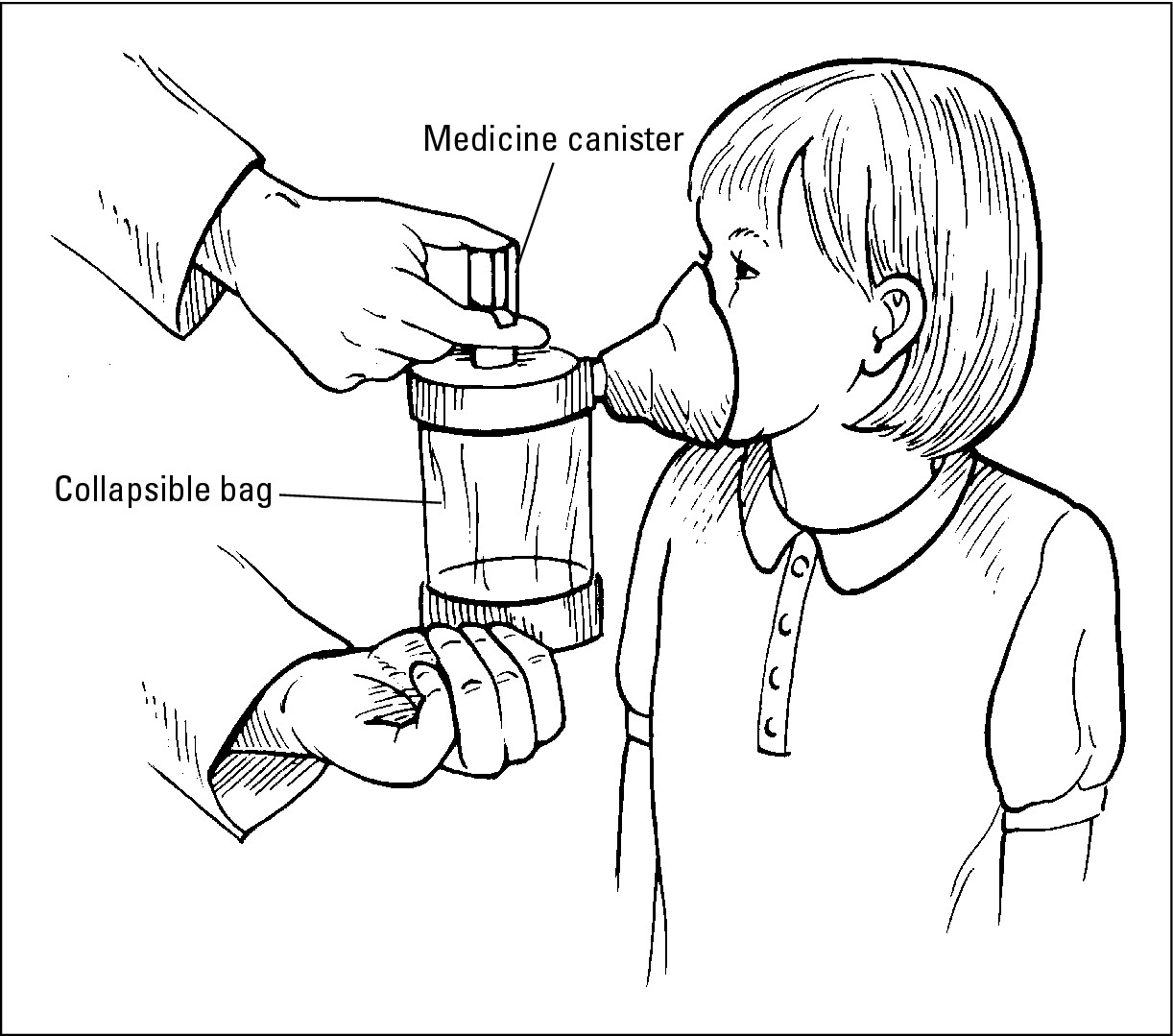

Figure 14-2: A child using an MDI with a holding chamber and mask. |

|

Some of the specific benefits of using a DPI include the following:

Children as young as 4 can use these devices.

Children as young as 4 can use these devices.

For many people who have poor MDI technique or who have difficulty coordinating the steps required for properly inhaling medication from an MDI, a DPI is often an excellent alternative, especially for children.

For many people who have poor MDI technique or who have difficulty coordinating the steps required for properly inhaling medication from an MDI, a DPI is often an excellent alternative, especially for children.

One inhalation from a DPI often provides the same dosage as two puffs of a comparable medication from an MDI.

One inhalation from a DPI often provides the same dosage as two puffs of a comparable medication from an MDI.

Because some DPIs have dose counters, you can easily tell when your inhaler is almost empty.

Because some DPIs have dose counters, you can easily tell when your inhaler is almost empty.

Cold temperatures don’t reduce the effectiveness of DPIs.

Cold temperatures don’t reduce the effectiveness of DPIs.

DPIs don’t use chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), so they don’t damage the planet’s ozone layer.

DPIs don’t use chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), so they don’t damage the planet’s ozone layer.

DPI instructions

Although DPIs don’t require using a holding chamber, you still need to use your DPI in a specific way. Because every DPI works a little differently, make sure you know how to use the one your doctor prescribes. As with an MDI (see “Using a metered-dose inhaler”), your physician should instruct you on how to properly use your DPI and should review your inhaler technique at subsequent office visits. The following are important, general instructions on the proper use of most DPIs:

1. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions to prime your DPI and then load a prescribed dose of the dry-powder medication.

2. Breathe out slowly and completely (usually for three to five seconds).

3. Put your mouth on the mouthpiece and inhale deeply and forcefully.

4. Hold your breath for ten seconds and then exhale slowly.

5. Repeat the procedure as outlined by your physician until you’ve taken the correct number of doses.

Getting the right dose from your DPI

Your DPI is breath-activated. That means you can control the rate at which you inhale the dry powder. However, you do need to inhale with sufficient force (minimal flow rate) in order to assure delivery of the medication to the smallest airways of your lungs. In order to be truly effective, using a DPI requires closing your mouth tightly around the inhaler’s mouthpiece and inhaling steadily, deeply, and forcefully.

Your DPI is breath-activated. That means you can control the rate at which you inhale the dry powder. However, you do need to inhale with sufficient force (minimal flow rate) in order to assure delivery of the medication to the smallest airways of your lungs. In order to be truly effective, using a DPI requires closing your mouth tightly around the inhaler’s mouthpiece and inhaling steadily, deeply, and forcefully.

Make sure the dry powder in your DPI stays dry to avoid caking or clumping, which can affect the dose’s reliability. For DPIs with caps, make sure you always replace the cap after using the product. Don’t ever wash a DPI that still contains medication.

Make sure the dry powder in your DPI stays dry to avoid caking or clumping, which can affect the dose’s reliability. For DPIs with caps, make sure you always replace the cap after using the product. Don’t ever wash a DPI that still contains medication.

In contrast with the operation of an MDI, you don’t need to shake your DPI just before using it in order to assure delivery of the proper dose. In fact, shaking some DPIs can result in losing dry powder.

In contrast with the operation of an MDI, you don’t need to shake your DPI just before using it in order to assure delivery of the proper dose. In fact, shaking some DPIs can result in losing dry powder.

Using a multidose-powder inhaler

Advair, a recently approved combination of fluticasone (an inhaled cortico-steroid) with salmeterol (a long-acting beta 2 -adrenergic bronchodilator), is formulated in a new type of delivery device known as a Diskus. As with other DPIs, the Diskus is breath-activated, and for the majority of patients, it’s easier to use than most MDIs.

The FDA approved this product, the first of its kind, to treat both the underlying inflammation that characterizes asthma and the airway constriction that often results from episodes of respiratory symptoms. Evidence suggests that using Advair Diskus usually reduces airway inflammation within one or two weeks (sometimes longer in certain cases), while the medication’s bronchodilation effects are usually felt within 30 to 60 minutes. However, remember that Advair Diskus isn’t a replacement for a quick-relief drug that your doctor prescribes for you to use if your respiratory symptoms worsen.

Important advantages of Advair Diskus include the following:

Each dose of Advair is effective for up to 12 hours. The normal dosage is one inhalation twice per day (for patients 12 years and older): once in the morning and once at night. This medication schedule is often more practical for patients than most MDI medications. As a result, patients using Advair Diskus are liable to be more successful in adhering to an asthma management plan.

Each dose of Advair is effective for up to 12 hours. The normal dosage is one inhalation twice per day (for patients 12 years and older): once in the morning and once at night. This medication schedule is often more practical for patients than most MDI medications. As a result, patients using Advair Diskus are liable to be more successful in adhering to an asthma management plan.

Using the Diskus requires far less coordination than most MDIs.

Using the Diskus requires far less coordination than most MDIs.

The built-in Diskus dose counter lets you keep track of every dose.

The built-in Diskus dose counter lets you keep track of every dose.

Operating your Diskus

If your physician prescribes Advair Diskus for you, make sure she explains the proper use of it.

1. While holding the device in one hand, place the thumb of your other hand on the device’s thumb grip and push away until the mouthpiece appears and snaps into position.

2. Hold the Diskus in a level, horizontal position with the mouthpiece facing you and slide the lever away from you as far as it goes until it clicks.

The “click” means the Diskus is ready for use.

3. Exhale, while holding the Diskus level but away from your mouth (never exhale into the Diskus mouthpiece).

4. Place the mouthpiece to your lips, breathe in quickly and deeply through the Diskus (don’t breathe in through your nose).

5. Remove the Diskus from your mouth and hold your breath for about ten seconds or as long you find comfortable; exhale slowly through your mouth.

6. Close the Diskus when you have completed taking a dose.

To do so, place your thumb once again on the thumb grip and slide it back toward you as far as it goes. The Diskus clicks shut, and the lever returns to its original position. The device is ready for your next dose, which you should take in approximately 12 hours (unless your doctor has advised you differently).

7. After taking your Diskus dose, rinse your mouth with water without swallowing.

Getting the right dose from your Diskus

Don’t advance the lever more than once when preparing your dose. Also, don’t play with the lever.

Don’t advance the lever more than once when preparing your dose. Also, don’t play with the lever.

Avoid tilting the Diskus when using it. Only use it in a level, horizontal position.

Avoid tilting the Diskus when using it. Only use it in a level, horizontal position.

Never try to take the Diskus apart.

Never try to take the Diskus apart.

Always keep the Diskus dry. Never wash any part of the device, including the mouthpiece.

Always keep the Diskus dry. Never wash any part of the device, including the mouthpiece.

Using nebulizers

A nebulizer is an air compressor connected to a generator. Nebulizers deliver medication as a mist that is easy to inhale, which often brings rapid symptom relief. These medication-delivery systems, sometimes known as breathing machines, are especially useful when a child is too young or too sick to use other devices. In addition to standard, home plug-in models, you can purchase portable nebulizers with battery packs or cigarette lighter adapters to use in a vehicle.

Although at times a bit more expensive in terms of the initial purchase price, the newer jet nebulizers are preferable to older units. The slight cost difference between these newer nebulizers and their precursor evaporates after patients begin using the more modern machines and realize how much more effectively they deliver medication throughout the airways.

Doctors typically recommend jet nebulizers as the delivery device for administering Pulmicort Respules, a commonly prescribed CDN formulation of the inhaled corticosteroid drug budesonide.

Place your mouth over the mouthpiece and breathe in and out.

Place your mouth over the mouthpiece and breathe in and out.

Make sure that you breathe through your mouth and not your nose.

Make sure that you breathe through your mouth and not your nose.

You or your child can use a facemask that covers the mouth and nose with the nebulizer. Some nebulizer manufacturers also offer colorful, kid-friendly pediatric masks. These masks usually feature animal shapes and can help in making the process of using a nebulizer more attractive — even fun in some cases — for young children.

Have an extra nebulizer mask on hand when using the device, especially if you’re administering the medication to a young child. (If you have a young child, you can probably imagine any number of reasons why that extra mask might come in handy).

Have an extra nebulizer mask on hand when using the device, especially if you’re administering the medication to a young child. (If you have a young child, you can probably imagine any number of reasons why that extra mask might come in handy).

.jpg)

When using a nebulizer on your child, don’t “blow by” or mist the medication in your child’s face. A nebulizer requires a closed system to provide effective treatment (I explain this aspect in greater detail in Chapter 18).

When using a nebulizer on your child, don’t “blow by” or mist the medication in your child’s face. A nebulizer requires a closed system to provide effective treatment (I explain this aspect in greater detail in Chapter 18).

Use all the medication in your nebulizer. (Doing so normally takes 7 to 15 minutes, depending on the type of nebulizer you’re using.)

Use all the medication in your nebulizer. (Doing so normally takes 7 to 15 minutes, depending on the type of nebulizer you’re using.)

Cleaning your medication delivery system

Rinse your MDI, holding chamber, and nebulizer daily and wash these devices weekly with a mild detergent to keep them clean and free of medication build-up. Don’t use harsh chemicals in washing your delivery devices, and make sure to follow the manufacturer’s instructions for maintenance and care. Also, don’t forget any MDIs that have been sitting in a drawer, backpack, briefcase, or handbag for a long time.

Remember to always keep the cap on your inhaler when you’re not using it. If the cap accidentally becomes dislodged, make sure you that you properly clean your inhaler before using it again.