Chapter 18

Asthma during Childhood

In This Chapter

Figuring out how asthma affects your child

Figuring out how asthma affects your child

Diagnosing your child’s condition

Diagnosing your child’s condition

Recognizing symptoms that suggest asthma

Recognizing symptoms that suggest asthma

Looking at special concerns

Looking at special concerns

Preventing asthma problems at school or daycare

Preventing asthma problems at school or daycare

P arents know that no one is more precious to them than their children. Therefore, parents want to treat any ailment that affects their youngsters as effectively as possible. If your child has asthma, the good news is that with a proper diagnosis, appropriate management, and a firm understanding of the disease, you can help your child effectively control his or her condition.

In fact, asthma — the most common chronic childhood disease in the United States — affects at least 5 million children. Current estimates are that only half of these youngsters receive accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Understanding Your Child’s Asthma

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that can make getting air in and especially out of the lungs difficult. Besides the serious health risks that asthma can pose for your child, properly managing the disease is vital for your youngster’s overall growth: Anything that restricts proper breathing can impair his or her physical and mental development.

Asthma often begins in childhood and affects boys more commonly than girls. Most children who develop asthma experience their first symptoms of the disease before they reach their third birthday.

Persistent coughing, wheezing, and recurring or lingering chest colds.

Persistent coughing, wheezing, and recurring or lingering chest colds.

An expanded or overinflated chest and hunched shoulders.

An expanded or overinflated chest and hunched shoulders.

Signs of coughing, wheezing, or extreme shortness of breath during or after exercise. These symptoms may signal the onset of exercise-induced asthma, or EIA (see “Participating in PE — exercise and asthma,” later in this chapter).

Signs of coughing, wheezing, or extreme shortness of breath during or after exercise. These symptoms may signal the onset of exercise-induced asthma, or EIA (see “Participating in PE — exercise and asthma,” later in this chapter).

Snoring, especially in preschool children. According to recent studies, a strong association exists between snoring and asthma in children ages 2 to 5.

Snoring, especially in preschool children. According to recent studies, a strong association exists between snoring and asthma in children ages 2 to 5.

Coughing at night, in the absence of other symptoms such as a cold.

Coughing at night, in the absence of other symptoms such as a cold.

Because you may find recognizing the preceding symptoms more difficult when observing infants and young children, watch for the following signs of possible asthma trouble:

.jpg)

Cyanosis, due to severe airway obstruction blocking the normal flow of oxygen into the lungs, causes a very pale or blue skin color. This can occur in a very severe asthma attack and requires emergency treatment.

Cyanosis, due to severe airway obstruction blocking the normal flow of oxygen into the lungs, causes a very pale or blue skin color. This can occur in a very severe asthma attack and requires emergency treatment.

Deep and rapid rib muscle movements, also known as retractions, which can occur when an infant or young child is having trouble breathing properly.

Deep and rapid rib muscle movements, also known as retractions, which can occur when an infant or young child is having trouble breathing properly.

Difficulty in nursing or eating.

Difficulty in nursing or eating.

Lethargic activity and reduced responses, including not recognizing or responding to parents.

Lethargic activity and reduced responses, including not recognizing or responding to parents.

Nasal flaring (rapidly moving nostrils), which can be a sign of severe asthma.

Nasal flaring (rapidly moving nostrils), which can be a sign of severe asthma.

Soft, shallow crying.

Soft, shallow crying.

In addition to these signs, you also need to consider the presence of atopy (the genetic susceptibility for the immune system to produce antibodies to common allergens, which leads to allergy symptoms) as a key predisposing factor for your child developing asthma (see Chapters 2 and 6).

Atopic conditions, including food allergies (see Chapter 8), allergic rhinitis (hay fever — see Chapter 7), and atopic dermatitis (eczema — see Chapter 1), can indicate a potential predisposition for asthma, especially in infants and young children. In fact, more than three-quarters of all children who develop asthma also have allergies. In many cases, allergic reactions associated with the response to inhalant and ingested allergens can also cause flare-ups in a child with asthma.

Inheriting asthma

If you think that your child may have asthma, consider your family’s medical history. Two-thirds of asthma patients have a close relative with the disease. Likewise, if you or your child’s other parent has asthma, your child’s chances of developing asthma are 25 percent; if both you and your child’s other parent have asthma, your child’s odds of developing asthma double to 50 percent.

Identifying children’s asthma triggers

Although hereditary factors may increase your child’s likelihood of developing asthma, environmental triggers and other precipitating factors usually bring on the symptoms. (See Chapter 5 for more detailed information on these triggers and precipitating factors.) Most physicians agree that viral respiratory infections are the most common triggers of asthma attacks in infants and young children.

The most serious air pollutant and irritant in terms of asthma is tobacco smoke. Parents absolutely should not smoke around a child, especially if the youngster has asthma. Even if your child is out (for example, at school), don’t smoke in the home. The lingering odor of tobacco smoke can still trigger your child’s asthma symptoms. According to numerous studies, exposure to maternal smoke is a major risk factor in the early onset of asthma in infancy. In fact, an infant whose mother smokes is almost twice as likely to develop asthma.

Controlling — not outgrowing — asthma

Your child’s sensitivities, however, may not entirely disappear, and the pos-sibility exists that a lack of treatment could result in irreversible airway changes. Clear and compelling evidence shows that early diagnosis and treatment results in fewer asthma symptoms.

Your child’s asthma symptoms may diminish or may no longer be apparent, but the increased airway sensitivity remains — just as your child’s fingerprints stay the same even though his or her body grows and develops. Asthma isn’t a disease that you can really cure; it’s a condition that you must control.

Treating early to avoid problems later

Identifying Childhood-Onset Asthma

When dealing with a child, particularly one who is very young, what may seem an obvious and easily identifiable asthma diagnosis isn’t always the case. Asthma is a complex condition with many possible combinations of symptoms that can vary widely from patient to patient. In fact, your child’s symptoms can change over time.

The process of diagnosing your child’s condition should include the following steps:

A complete medical history

A complete medical history

A physical examination

A physical examination

Lung-function tests

Lung-function tests

Any other tests that your doctor considers necessary to determine the nature of your child’s ailment

Any other tests that your doctor considers necessary to determine the nature of your child’s ailment

Your child experiences episodes of airway obstruction.

Your child experiences episodes of airway obstruction.

The airway obstruction is at least partially reversible.

The airway obstruction is at least partially reversible.

Your child’s symptoms result from asthma, not other potential conditions that I explain in the “All That Wheezes Isn’t Asthma” section, later in this chapter.

Your child’s symptoms result from asthma, not other potential conditions that I explain in the “All That Wheezes Isn’t Asthma” section, later in this chapter.

Taking your child’s medical history

Any family history of allergies and/or asthma. (As I explain in the “Inheriting asthma” section of this chapter, genetics play a major role in asthma development.)

Any family history of allergies and/or asthma. (As I explain in the “Inheriting asthma” section of this chapter, genetics play a major role in asthma development.)

Any exposures your child receives to common asthma triggers, such as inhalant allergens and irritants — especially tobacco smoke — or any other substances, as well as the precipitating factors that I describe in “Identifying children’s asthma triggers,” earlier in this chapter.

Any exposures your child receives to common asthma triggers, such as inhalant allergens and irritants — especially tobacco smoke — or any other substances, as well as the precipitating factors that I describe in “Identifying children’s asthma triggers,” earlier in this chapter.

Any times your child has been hospitalized for respiratory problems. Your doctor should also ask about any medications that your child takes, whether for respiratory symptoms or for other conditions.

Any times your child has been hospitalized for respiratory problems. Your doctor should also ask about any medications that your child takes, whether for respiratory symptoms or for other conditions.

Examining your child for signs of asthma

The focus of a physical exam for children with suspected asthma usually involves the following:

Checking for signs of hunched shoulders, chest deformities, and pale skin.

Checking for signs of hunched shoulders, chest deformities, and pale skin.

Examining your child’s breathing passageways, from nose to chest. (See Chapter 2 for details of physical exams.)

Examining your child’s breathing passageways, from nose to chest. (See Chapter 2 for details of physical exams.)

Looking for evidence of other atopic diseases, such as allergic rhinitis or atopic dermatitis, which may indicate a predisposition to asthma.

Looking for evidence of other atopic diseases, such as allergic rhinitis or atopic dermatitis, which may indicate a predisposition to asthma.

Observing your child’s breathing rate and rhythm. Your doctor listens with a stethoscope to the chest and back over areas of your child’s lungs to check for the following signs and sounds of airway obstruction:

Observing your child’s breathing rate and rhythm. Your doctor listens with a stethoscope to the chest and back over areas of your child’s lungs to check for the following signs and sounds of airway obstruction:

• Wheezing or other sounds not usually associated with normal breathing

• Unusually prolonged exhalations

• Rapid, shallow respirations (panting) in more severe cases

Testing your child’s lungs

After taking your child’s medical history and performing a physical examination, your doctor may conduct lung-function tests if your child is older than 4 or 5 years old. These tests are vital in diagnosing asthma because they can tell whether airway obstruction has limited or affected your child’s lung functions.

Spirometry tests are difficult, if not impossible, to perform on children under 4 years old. However, by age 6, most children are quite capable of performing accurate and reliable spirometry (if they feel like it!). To properly diagnose an infant or young child with asthma, your doctor may need to rely on your child’s medical history and physical examination. In some cases, your doctor may prescribe a trial course of a nebulized beta 2 -adrenergic bronchodilator and/or anti-inflammatory medications to evaluate your child’s response.

All That Wheezes Isn’t Asthma

Abnormal development of blood vessels, known as vascular rings, around the trachea (windpipe) and esophagus

Abnormal development of blood vessels, known as vascular rings, around the trachea (windpipe) and esophagus

Congenital heart disease, often leading to congestive heart failure

Congenital heart disease, often leading to congestive heart failure

Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis

Viral and/or bacterial bronchitis or pneumonia

Viral and/or bacterial bronchitis or pneumonia

Viral bronchiolitis (RSV), a serious respiratory infection that can occur in the first two years of life

Viral bronchiolitis (RSV), a serious respiratory infection that can occur in the first two years of life

RSV may resemble an acute asthma attack. This disease characteristically occurs during the winter months in children under 2 years of age. Studies have shown that more than half of children who experience infections of viral bronchiolitis and who have a family history of allergy go on to develop asthma.

Vocal cord dysfunction (VCD)

Vocal cord dysfunction (VCD)

.jpg)

Focusing on Special Issues Concerning Childhood Asthma

After your child’s doctor has diagnosed your child’s asthma, the doctor should develop an appropriate asthma management plan, in consultation with you and your child (if he or she is old enough to participate). Your child’s plan should consist of specific avoidance, medication, monitoring, and assessment measures, and it should also provide steps that you and/or your child can take in case his or her asthma symptoms suddenly worsen.

Reducing your child’s level of exposure to asthma and allergy triggers. I describe these triggers in “Identifying children’s asthma triggers,” earlier in this chapter. (For detailed tips and information on avoidance measures, trigger control, and allergy-proofing, see Chapter 5.)

Reducing your child’s level of exposure to asthma and allergy triggers. I describe these triggers in “Identifying children’s asthma triggers,” earlier in this chapter. (For detailed tips and information on avoidance measures, trigger control, and allergy-proofing, see Chapter 5.)

Monitoring your child’s peak-flow rates. Your doctor should show you and your child (if your youngster is older than 4 years old) how to use a peak-flow meter. (See “Peak-flow meters and school-age children [ages 5 to 12],” later in this chapter.) Using this simple device at home and school to measure peak expiratory flow rates (PEFR) can help detect early deterioration of asthma, prompting you or your child to make the appropriate change in medications or, if needed, to seek medical attention.

Monitoring your child’s peak-flow rates. Your doctor should show you and your child (if your youngster is older than 4 years old) how to use a peak-flow meter. (See “Peak-flow meters and school-age children [ages 5 to 12],” later in this chapter.) Using this simple device at home and school to measure peak expiratory flow rates (PEFR) can help detect early deterioration of asthma, prompting you or your child to make the appropriate change in medications or, if needed, to seek medical attention.

.jpg)

Children and their parents very often don’t perceive the early symptoms of worsening asthma without a peak-flow meter. As a result, you may not understand or notice when your child’s asthma symptoms worsen, thus critically delaying the proper medical treatment. (For detailed instructions on using peak-flow meters, see Chapter 4.)

Assessing and monitoring your child’s lung functions during regular office visits. These tests and assessments, as well as the PEFR numbers that you (or your child) record in an asthma symptom diary (see Chap-ter 4), are vital to tracking how your child’s condition develops and responds to prescribed treatment.

Assessing and monitoring your child’s lung functions during regular office visits. These tests and assessments, as well as the PEFR numbers that you (or your child) record in an asthma symptom diary (see Chap-ter 4), are vital to tracking how your child’s condition develops and responds to prescribed treatment.

Using long-term preventive medications that control your child’s underlying airway inflammation, congestion, constriction, and hyperresponsiveness. (See Chapter 2 for details of how asthma affects the body.)

Using long-term preventive medications that control your child’s underlying airway inflammation, congestion, constriction, and hyperresponsiveness. (See Chapter 2 for details of how asthma affects the body.)

Implementing an asthma management plan for your child’s school or daycare. Prepare an emergency asthma management plan, which specifies short-term, fast-acting rescue medications for use only in the event that your child’s condition suddenly deteriorates. This type of action plan should also clearly explain how to adjust your child’s medications in response to particular signs, symptoms, and PEFR levels. Likewise, this action plan should tell you (or your child) when to call for medical help. (See “Handling Asthma at School and Daycare,” later in this chapter, for more information.)

Implementing an asthma management plan for your child’s school or daycare. Prepare an emergency asthma management plan, which specifies short-term, fast-acting rescue medications for use only in the event that your child’s condition suddenly deteriorates. This type of action plan should also clearly explain how to adjust your child’s medications in response to particular signs, symptoms, and PEFR levels. Likewise, this action plan should tell you (or your child) when to call for medical help. (See “Handling Asthma at School and Daycare,” later in this chapter, for more information.)

Educating yourself, your child, your child’s teacher, and your family. This education can involve information and resources that your doctor, clinic staff, and patient support groups provide or recommend, as well as relevant books, newsletters, videos, and other helpful materials. (See the appendix for information on these resources.)

Educating yourself, your child, your child’s teacher, and your family. This education can involve information and resources that your doctor, clinic staff, and patient support groups provide or recommend, as well as relevant books, newsletters, videos, and other helpful materials. (See the appendix for information on these resources.)

Teaming up for the best treatment

Managing asthma in infants (newborns to 2 years old)

The most difficult part of treating an infant with asthma is that the child isn’t old enough to tell you what’s wrong. Unfortunately, no devices are currently available for practicing physicians to use in order to measure infants’ lung functions. Special techniques do exist at a few major medical centers at this time, but scientists only use them for research purposes and not in clinical practice. Therefore, determining the extent and type of your baby’s respiratory problems can present some unique challenges. In these cases, your doctor mainly relies on medical history (including family history), physical examination, and response to medical therapy.

Depending on your child’s condition, your doctor may prescribe some of the following medications to control your baby’s asthma:

If your infant’s asthma symptoms are mild or intermittent, his or her doctor may prescribe an inhaled, short-acting beta

2

-adrenergic in a nebulizer or oral beta

2

-adrenergic syrup to reduce airway obstruction. Your doctor also can prescribe a recently approved pediatric, oral gran-ule formulation of montelukast (Singulair) for ages 12 to 23 months. Administer the medication directly into the baby’s mouth or by mixing it with the baby’s soft food. According to the product insert, the recommended foods are applesauce, carrots, rice, or ice cream.

If your infant’s asthma symptoms are mild or intermittent, his or her doctor may prescribe an inhaled, short-acting beta

2

-adrenergic in a nebulizer or oral beta

2

-adrenergic syrup to reduce airway obstruction. Your doctor also can prescribe a recently approved pediatric, oral gran-ule formulation of montelukast (Singulair) for ages 12 to 23 months. Administer the medication directly into the baby’s mouth or by mixing it with the baby’s soft food. According to the product insert, the recommended foods are applesauce, carrots, rice, or ice cream.

If your child suffers from more severe symptoms, your doctor may prescribe a daily, long-term preventive medication, such as cromolyn (Intal) via nebulizer or inhaler; nedocromil (Tilade) via inhaler; an inhaled corticosteroid (Flovent) via inhaler; or a nebulizer form of budesonide (Pulmicort Respules). Because of your child’s young age, administering any of these medications with an inhaler requires using a holding chamber (spacer) and a mask. Occasionally, your child’s doctor may also recommend theophylline in a syrup, tablet (crushed), or capsule (sprinkled) form. (See Chapters 14 and 15 for information on asthma medications and delivery devices.)

If your child suffers from more severe symptoms, your doctor may prescribe a daily, long-term preventive medication, such as cromolyn (Intal) via nebulizer or inhaler; nedocromil (Tilade) via inhaler; an inhaled corticosteroid (Flovent) via inhaler; or a nebulizer form of budesonide (Pulmicort Respules). Because of your child’s young age, administering any of these medications with an inhaler requires using a holding chamber (spacer) and a mask. Occasionally, your child’s doctor may also recommend theophylline in a syrup, tablet (crushed), or capsule (sprinkled) form. (See Chapters 14 and 15 for information on asthma medications and delivery devices.)

Physicians prescribe theophylline syrup or suggest emptying beaded contents of a theophylline capsule on food such as applesauce so that your baby can easily ingest the medication.

In the event that your child suffers a severe asthma episode, your child’s doctor may prescribe a short course of oral corticosteroids, available in syrup form (Orapred, Prelone, Pediapred) or as a tablet (prednisone).

In the event that your child suffers a severe asthma episode, your child’s doctor may prescribe a short course of oral corticosteroids, available in syrup form (Orapred, Prelone, Pediapred) or as a tablet (prednisone).

Listening to your children

Because children under 2 years old aren’t able to use a peak-flow meter, you may consider using a stethoscope to listen to your child’s lungs. Some parents find that using a stethoscope can help them detect an asthma attack in their infant or young child at an earlier stage and may enable them to more accurately report their youngster’s asthma symptoms to their child’s physician.

Consult your child’s physician to see whether using a stethoscope can help you. Likewise, ask your doctor for instructions on using the device properly. Keep in mind that a stethoscope detects breathing problems only if your child’s lung function drops by about 25 percent.

Using a nebulizer with your infant or toddler

If your doctor prescribes nebulizer therapy for your infant or toddler, make sure that you, as well as any other person who may be taking care of your child (such as a nanny, babysitter, and/or daycare provider), understand how to use a nebulizer appropriately and effectively. Using this device may challenge an older child, but for an infant or toddler who may be struggling to breathe, using a nebulizer can prove especially difficult. Chapter 14 provides more detailed instructions and tips on using nebulizers properly and effectively.

If your child isn’t experiencing sudden-onset severe respiratory symptoms, you can introduce the mask initially, before running the air compressor component of the machine. The air compressor can be noisy, and it may frighten your child at first. If your child suffers more severe symptoms, hold the mask fairly close to his or her face and then slowly move it closer until the mask is properly in place.

Delivering nebulizer doses properly

.jpg)

Treating toddlers (ages 2 to 5 years): Medication challenges

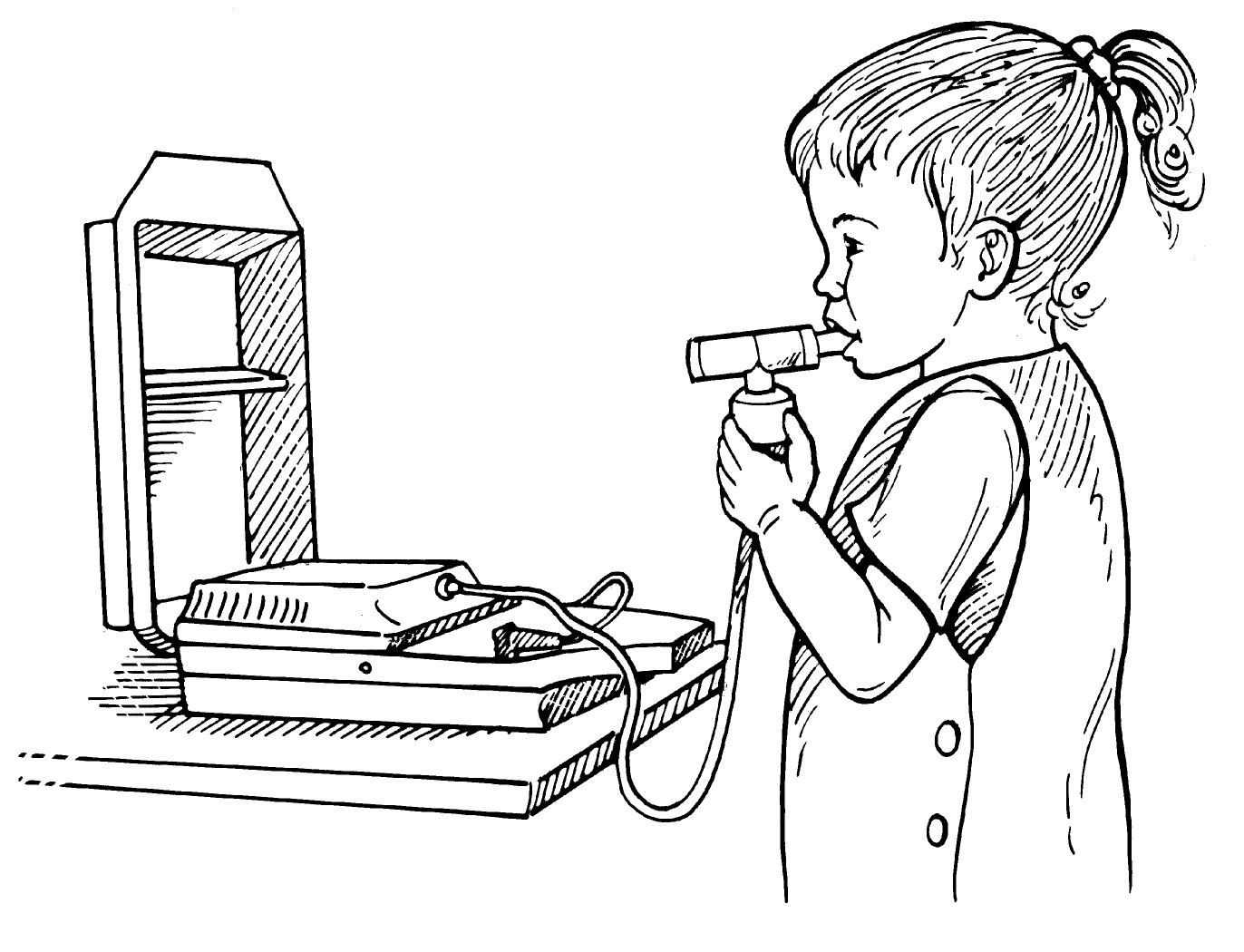

Few medications are available in the United States for children ages 2 to 5 years. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently approved the use of montelukast (Singulair), a leukotriene modifier (see Chapter 15), in a 4-milligram chewable tablet, for use in this age group. However, inhaled topical corticosteroids and long-acting inhaled beta 2 -adrenergic (beta 2 -agonist) bronchodilators (or nonsedating antihistamines for allergic rhinitis) aren’t specifically formulated for children under 4 years. Therefore, nebulizer use can be extremely important during the toddler and early school-age years (see Figure 18-1).

Fortunately, the U.S. Congress has established a program of incentives to encourage pharmaceutical manufacturers to conduct clinical trials of med-ications, including those for asthma, in the pediatric age group. In fact, FDA regulations require pharmaceutical companies to submit detailed plans for studying formulations specifically for children (for example, syrups and chewable tablets) when seeking approval for development of new drugs. With hope, this program can lead to improved medical treatments for young children with asthma and other allergic diseases.

|

Figure 18-1: Young child using a nebulizer. |

|

Because very few effective asthma medications have gone through the drug development process for FDA approval for use with children under 4 years of age, many doctors prescribe drugs that haven’t been studied extensively for use in that age group. Therefore, determining the appropriate dosages of asthma medications for toddlers can prove challenging. Children react differently to medications than do adults, and determining the correct dosage for children isn’t as simple as assuming that the toddler receives half of an adult dose.

Peak-flow meters and school-age children (ages 5 to 12)

By the time children reach age 5, they can generally use a peak-flow meter at home. This device allows you and your doctor to assess the state of your child’s lungs. Using a peak-flow meter each morning and night can help you and your child manage his or her asthma in the following ways:

Educate both you and your child about what works in terms of treatment and what triggers may cause problems

Educate both you and your child about what works in terms of treatment and what triggers may cause problems

Enable you to discuss your child’s condition in terms of specific criteria, thus enhancing communication between you and your child’s doctor

Enable you to discuss your child’s condition in terms of specific criteria, thus enhancing communication between you and your child’s doctor

Provide an objective way of tracking your child’s response to his or her asthma medications

Provide an objective way of tracking your child’s response to his or her asthma medications

Warn you and your child that an asthma episode is looming

Warn you and your child that an asthma episode is looming

Establishing your child’s personal best peak-flow rate enables you and your child to tell when problems occur, because you can note when the rate goes down according to the green, yellow, and red zones of the peak-flow zone system. For more information on using peak-flow meters, turn to Chapter 4.

Getting kids into clinical trials

Conducting clinical trials with young children — especially those under 4 years — is very costly and time-consuming compared to clinical trials involving children older than 12 years and adults. Because of the great need for pediatric patient participation, make a commitment to enroll your asthmatic infant and toddler for clinical trials. Doing so can help develop new and better medications that benefit all children. In addition, you and your child can probably discover a great deal about asthma and its management, and you may love all the extra attention while participating in these studies. In addition, the medicines being tested are free, and patients are reimbursed for their time and travel while participating in a clinical trial.

Pharmaceutical companies also need to make a commitment to conduct trials for younger children. These trials may cost more and prove difficult, but the lives and health of young children depend on such studies.

Using inhalers: Teens and asthma

Many teens with asthma feel different and insecure because of their disease. Unfortunately, adolescent anxieties about fitting in and being cool can result in teen asthmatics ignoring or not properly managing their disease. In some cases, adolescents may even allow their symptoms to worsen rather than simply taking a whiff or two from their inhalers.

Handling Asthma at School and Daycare

If your child has asthma, inform the teachers, administrators, and school nurse about your child’s condition. Some schools and daycare centers institute asthma management programs that provide the following:

Policies and procedures for administering students’ medications.

Policies and procedures for administering students’ medications.

Specific actions for staff members to perform within the program.

Specific actions for staff members to perform within the program.

These actions may include establishing clear policies on taking medications during school hours, designating one person on the school staff to maintain each student’s asthma plan, and generally working with parents, teachers, and the school nurse (if one is available) to provide the most support possible for students with asthma, especially so they can have access to medications they may need while at school.

An action plan for treating students’ asthma episodes.

An action plan for treating students’ asthma episodes.

Whether or not the school or daycare center administers such a program, take the following steps to ensure that your child’s school days are as healthy, safe, and fulfilling as possible:

• Meet with school staff to inform them about any medications your child may need to take while on campus, as well as any physical activity restrictions that your doctor may advise. (Properly managing their condition allows most children with asthma to participate in sports and PE classes.)

• File treatment authorization forms with the school office and discuss what school personnel must do if your child suffers an asthma emergency. Also, provide instructions on how to reach you and your child’s physician during an emergency.

• Inform school personnel of allergens and irritants that can trigger your child’s asthma symptoms, such as pets in the classroom, and request that the school remove the sources of those triggers, if possible.

.jpg)

Indoor air quality (IAQ) at school and daycare

From about the age of 2, most children spend the majority of their waking hours at school or daycare. Therefore, ensuring that these environments are as free of potential asthma triggers as possible is essential to your child’s health.

Outdoor smoke, soot, chemicals, pollens, and mold spores

Outdoor smoke, soot, chemicals, pollens, and mold spores

Animal dander from a furry classroom pet

Animal dander from a furry classroom pet

Indoor mold from ventilation ducts as well as indoor irritants such as tobacco smoke, scents from printers and copiers, and fumes from heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems

Indoor mold from ventilation ducts as well as indoor irritants such as tobacco smoke, scents from printers and copiers, and fumes from heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems

Many students, teachers, administrators, and other personnel experience similar symptoms.

Many students, teachers, administrators, and other personnel experience similar symptoms.

Your child’s symptoms (and those of other affected people) improve or disappear after school or daycare.

Your child’s symptoms (and those of other affected people) improve or disappear after school or daycare.

Symptoms begin to appear rapidly following physical changes, such as construction work, painting, or pesticide use at the school or daycare.

Symptoms begin to appear rapidly following physical changes, such as construction work, painting, or pesticide use at the school or daycare.

Your child and other people with allergies or asthma only experience symptoms inside the building.

Your child and other people with allergies or asthma only experience symptoms inside the building.

Participating in PE — exercise and asthma

.jpg)

Your child’s doctor may prescribe medications to control and prevent EIA, as well as advise appropriate warm-up and cool-down activities that can also reduce the risk of EIA. Having an action plan in place prior to an emergency can ensure that your child receives the proper treatment when he or she needs it most. Part of that plan should include providing immediate access to your child’s rescue drug in case it’s needed to treat the onset of any acute respiratory symptoms.