Chapter 2

The Basics of Treating and Managing Your Asthma

In This Chapter

Identifying who’s affected by asthma and why

Identifying who’s affected by asthma and why

Understanding the many dimensions of asthma

Understanding the many dimensions of asthma

Connecting the dots between your airways and asthma

Connecting the dots between your airways and asthma

Diagnosing your condition

Diagnosing your condition

Undertaking an asthma management plan

Undertaking an asthma management plan

A sthma isn’t a recurring chest cold, a psychological disorder, a minor annoyance, or a condition that you usually outgrow. It’s a multifaceted, chronic, inflammatory airway disease of the lungs that causes breathing problems and that requires proper diagnosis, early and aggressive treatment, and effective long-term management. Asthma is also unfortunately an ailment that many people — asthmatics themselves, family members, and even some doctors — may not recognize or may improperly diagnose, often as a chest cold or bronchitis.

Doctors don’t yet clearly understand the origin of the airway inflammation that characterizes asthma. However, researchers have determined that this underlying inflammation often results in hyperresponsive (“twitchy”), constricted, and congested airways, which are increasingly liable to react to asthma triggers (see Chapter 5 for an extensive discussion of these triggers).

Understanding Who Gets Asthma and Why

The strongest predictor that an individual may develop asthma is a family history of allergies and asthma and/or atopy, an inherited tendency to develop hypersensitivities to allergic triggers. This tendency is almost always due to an overactive immune system that produces elevated levels of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies to allergens. (See Chapter 6 for an extensive discussion of this process.)

The predisposition to asthma is inherited. This genetic inheritance can be a significant factor in developing the condition: Two-thirds of asthma patients have a family member who also has the disease.

Most cases of asthma are of an allergic nature (known as allergic asthma ), and usually begin to manifest during childhood, affecting boys more often than girls. In fact, asthma is the most common chronic disease of childhood. Other allergic disorders, such as food allergies, atopic dermatitis (allergic eczema), or allergic rhinitis (hay fever), which are also indicators of atopy in young children, can precede this form of the ailment, often referred to as childhood-onset asthma.

Adult-onset asthma, which is less common than childhood-onset asthma, develops in adults older than 40, more often in women. Atopy doesn’t appear to play a role in these cases. Rather, adult-onset asthma more often seems to be triggered by various nonallergic mechanisms, including sinusitis, upper respiratory infections, nasal polyps, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), sensitivities to aspirin and related nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), as well as occupational exposures to chemicals, such as those found in fumes, gases, resins, dust, and insecticides. However, many episodes seem to occur spontaneously without known triggers.

Important symptoms of asthma in infancy and early childhood include persistent coughing, wheezing, and recurring or lingering chest colds.

Important symptoms of asthma in infancy and early childhood include persistent coughing, wheezing, and recurring or lingering chest colds.

Inflammation of the airways is the single most important underlying factor in asthma. If you have asthma, your symptoms may come and go, but the underlying inflammation usually persists. Episodes of asthma symptoms can vary in length from minutes to hours and even from days to weeks, depending on your medical treatment (see Chapter 4), the severity of your symptoms (see Chapter 14), and the character of the triggering mechanism (see Chapter 5).

Inflammation of the airways is the single most important underlying factor in asthma. If you have asthma, your symptoms may come and go, but the underlying inflammation usually persists. Episodes of asthma symptoms can vary in length from minutes to hours and even from days to weeks, depending on your medical treatment (see Chapter 4), the severity of your symptoms (see Chapter 14), and the character of the triggering mechanism (see Chapter 5).

Although no cure exists for asthma, in most cases you can manage and even reverse the effects of the disease. However, poorly managed or undertreated asthma may lead to loss of airway functions and, in some cases, irreversible lung damage as a result of airway remodeling. (I explain airway remodeling in the section “How airway obstruction develops,” later in this chapter.)

Although no cure exists for asthma, in most cases you can manage and even reverse the effects of the disease. However, poorly managed or undertreated asthma may lead to loss of airway functions and, in some cases, irreversible lung damage as a result of airway remodeling. (I explain airway remodeling in the section “How airway obstruction develops,” later in this chapter.)

Early, aggressive treatment with appropriate medication is vital to effectively managing your asthma.

Early, aggressive treatment with appropriate medication is vital to effectively managing your asthma.

Why aren’t these antibiotics curing my bronchitis?

Bronchitis is a general term for inflammation of the bronchi, or airways. (Itis is Greek for swelling or inflammation.) The most frequent causes of bronchial or airway inflammation are viral or bacterial infections, smoking, or asthma.

Because the coughing symptoms in different types of airway inflammation can appear similar and because bacterial infections of the airway are common, some patients who actually have asthma often are mistakenly treated with antibiotics. Although these drugs can clear bacterial infections of the airways, they don’t relieve or control asthma symptoms.

If you experience lingering coughs, recurring colds, or similar symptoms that could indicate bronchitis, make sure that your doctor performs appropriate lung-function tests to check for reversible airflow obstruction, a hallmark of asthma. Performing such tests gives doctors the information they need to prescribe appropriate and effective treatment for your condition.

Identifying triggers, attacks, episodes, and symptoms

A wide variety of allergens, irritants, and other factors, such as colds, flu, exercise, and drug sensitivities, can trigger asthma symptoms — what you may refer to as asthma attacks or asthma episodes. (See Chapter 5 for more information about asthma triggers and how to avoid them.) Asthma symptoms can range from decreased tolerance to exercise to feeling completely out of breath and from persistent coughing to wheezing, chest tightness, or life-threatening respiratory distress. In many cases, a bothersome cough may be the only symptom of asthma that you even notice.

.jpg)

Realizing that asthma isn’t in your head

Allergies and asthma all over the world

According to numerous samples of populations in many countries, large numbers of people have allergic sensitivities that frequently increase their risk of developing symptoms associated with asthma. Here’s a sampling of allergy and asthma surveys from the around the globe:

Almost half the U.S. population has some sensitivity to allergens, and a third of homes in the United States contain conditions such as elevated humidity levels that frequently lead to significant sources of household allergens like molds and dust mites. (See Chapter 10 for practical and important tips on allergy-proofing your home.)

Almost half the U.S. population has some sensitivity to allergens, and a third of homes in the United States contain conditions such as elevated humidity levels that frequently lead to significant sources of household allergens like molds and dust mites. (See Chapter 10 for practical and important tips on allergy-proofing your home.)

Based on allergy skin testing (see Chapter 11), at least half of all children in Hong Kong and other Chinese cities demonstrate allergic sensitivities, especially to cockroach and dust mite allergens. Likewise, as many as one-quarter of schoolchildren in Costa Rica may have asthma.

Based on allergy skin testing (see Chapter 11), at least half of all children in Hong Kong and other Chinese cities demonstrate allergic sensitivities, especially to cockroach and dust mite allergens. Likewise, as many as one-quarter of schoolchildren in Costa Rica may have asthma.

Studies in Germany found that at least one-third of Germans have sensitivities to pollens, dust mites, and other common inhalant allergens, while as many as a quarter of that country’s population experiences symptoms of asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Studies in Germany found that at least one-third of Germans have sensitivities to pollens, dust mites, and other common inhalant allergens, while as many as a quarter of that country’s population experiences symptoms of asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Research in India shows that as many as one-fifth of Bombay residents have hyperresponsive airways, a significant indicator of asthma (see Chapter 5), and equivalent numbers also experience sensitivities to dust mites.

Research in India shows that as many as one-fifth of Bombay residents have hyperresponsive airways, a significant indicator of asthma (see Chapter 5), and equivalent numbers also experience sensitivities to dust mites.

Australia and New Zealand consistently report two of the highest incidences of childhood asthma in the world. In Australia, the prevalence of childhood asthma has been reported as high as more than 20 percent in certain childhood age groups, while in New Zealand, comparable studies reveal a prevalence of asthma of more than 16 percent in similar childhood age groups.

Australia and New Zealand consistently report two of the highest incidences of childhood asthma in the world. In Australia, the prevalence of childhood asthma has been reported as high as more than 20 percent in certain childhood age groups, while in New Zealand, comparable studies reveal a prevalence of asthma of more than 16 percent in similar childhood age groups.

If you’re thinking of moving to the desert to escape your allergies, consider the significant numbers of allergists in the telephone directories of cities such as Phoenix or Tucson, and also consider this: Studies in Kuwait show that as many as a quarter of Kuwaitis experience some sensitivity to dust mites.

If you’re thinking of moving to the desert to escape your allergies, consider the significant numbers of allergists in the telephone directories of cities such as Phoenix or Tucson, and also consider this: Studies in Kuwait show that as many as a quarter of Kuwaitis experience some sensitivity to dust mites.

Uncovering the Many Facets of Asthma

Asthma can show up in various ways. The underlying mechanism causing many of the symptoms of asthma is due to a complex series of events involving many types of cells and tissue that reside in your lungs. I explain this process further in the section “Asthma and Your Airways,” later in this chapter.

Because such a wide range of factors can precipitate asthma symptoms, and because certain triggers can cause stronger reactions in some asthma patients than in others, doctors often classify asthma according to the triggers that instigate your symptoms. Classifying asthma in this way can help you and your doctor understand the cause of your symptoms.

Although a certain precipitating factor may predominate in many asthma cases, multiple triggers affect the majority of people with asthma. For example, most asthmatics have exercise-induced asthma (EIA), sometimes known as exercise-induced bronchospasm (EIB) — which I explain in the “Exercise-induced asthma (EIA)” section — in addition to asthma that manifests from other triggers or precipitating factors. The next sections list the main asthma classifications that many doctors use.

Allergic asthma

Throughout the world, triggers of this common form of asthma include inhalant allergens, such as dust mites, animal dander, fungal spores, and pollens from trees, grasses, and weeds. If you suffer from allergic asthma, you may be sensitive to a combination of these allergens and probably suffer from allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and/or allergic conjunctivitis, which I explain in detail in Chapter 7.

Immunotherapy can, in certain cases, reduce your level of sensitivity to the allergens that affect you, thus decreasing your allergy and asthma symptoms. (To find out more about immunotherapy, turn to Chapter 11.)

Nonallergic asthma

Irritants, such as tobacco smoke, household cleaners, soaps, perfumes and scents, glue, aerosols, smoke from wood-burning appliances or fireplaces, fumes from unvented gas, oil, or kerosene stoves, and indoor and outdoor air pollutants can also trigger asthma.

Upper respiratory tract infections, such as the common cold and flu, as well as sinusitis, nasal polyps, GERD, and aspirin sensitivity (see “Aspirin-induced [and food-additive-induced] asthma,” later in this chapter), may also aggravate airway inflammation and trigger asthma symptoms in some people.

Occupational asthma

Current estimates are that occupational asthma, which a wide range of allergens and irritants can trigger, affects as many as 15 percent of asthma patients in the United States. The precipitating factors in occupational asthma cases often include exposure to fumes, chemicals, gases, resins, metals, dust, insecticides, vapors, and other substances in the workplace that can induce or aggravate airway inflammation.

Exercise-induced asthma (EIA)

Symptoms of exercise-induced asthma (EIA) occur to varying degrees in a majority of asthmatics. Exercising that involves breathing cold, dry air — such as running outdoors in winter — may trigger EIA symptoms more often than activities that involve breathing warmer, humidified air, such as swimming in a heated pool.

Aspirin-induced (and food- additive-induced) asthma

A significant number of people who have both asthma and nasal polyps may experience intensified asthma symptoms if they take aspirin and related medications, such as over-the-counter NSAIDs and newer prescription NSAIDs, known as COX-2 inhibitors, such as celecoxib (Celebrex) and rofecoxib (Vioxx). Some asthma sufferers may also experience intensified symptoms if they ingest sulfites (preservatives found in beer, wine, and many processed foods) or tartrazine (FDC yellow dye No. 5), which is used in many medications, foods, and vitamin products.

Asthma and Your Airways

Your airways are vital to your health. This network of bronchial tubes enables your lungs to absorb oxygen into the bloodstream and eliminate carbon dioxide — the process called respiration, or breathing. Most people take breathing for granted — you usually don’t need to think about it, unless something interferes with this process by obstructing your airways.

The inflammatory response

Airway hyperresponsiveness

Airway hyperresponsiveness

Airway constriction

Airway constriction

Airway congestion

Airway congestion

Burning your lungs

You need to realize that the ongoing, underlying airway inflammation is often so subtle that it can go unnoticed. Asthma symptoms are often just the tip of the iceberg. If you have asthma, the inflammation smolders away in your airways, whether or not you’re actually experiencing symptoms.

Imagine if you had a rash or sunburn and only took pain relievers to deal with the discomfort, rather than staying out of the sun or treating the cause of the problem. The underlying airway inflammation in asthma is similar to having a sunburn in your bronchial tubes, as my good friend Nancy Sander, founder of the Allergy and Asthma Network/Mothers of Asthmatics (AANMA), likes to explain. If you suffer from asthma, the insides of your airways are often red and inflamed, and, as with a bad rash or sunburn, the top layer of airway tissue may peel.

What you can’t see can hurt you

As I explain in the section “Testing your lungs,” later in the chapter, you need to make sure that your doctor performs appropriate pulmonary (lung) function tests if you have bouts of wheezing, recurring coughs, lingering colds, or other symptoms that could indicate an underlying respiratory ailment.

Breathing basics: How your lungs function

To better understand how asthma adversely affects your airways, consider what happens in normal breathing:

1. The air you inhale flows through your nose or mouth into your trachea, or windpipe.

2. Your trachea then divides into right and left main bronchi (or branches), splitting and funneling the air into each of your lungs.

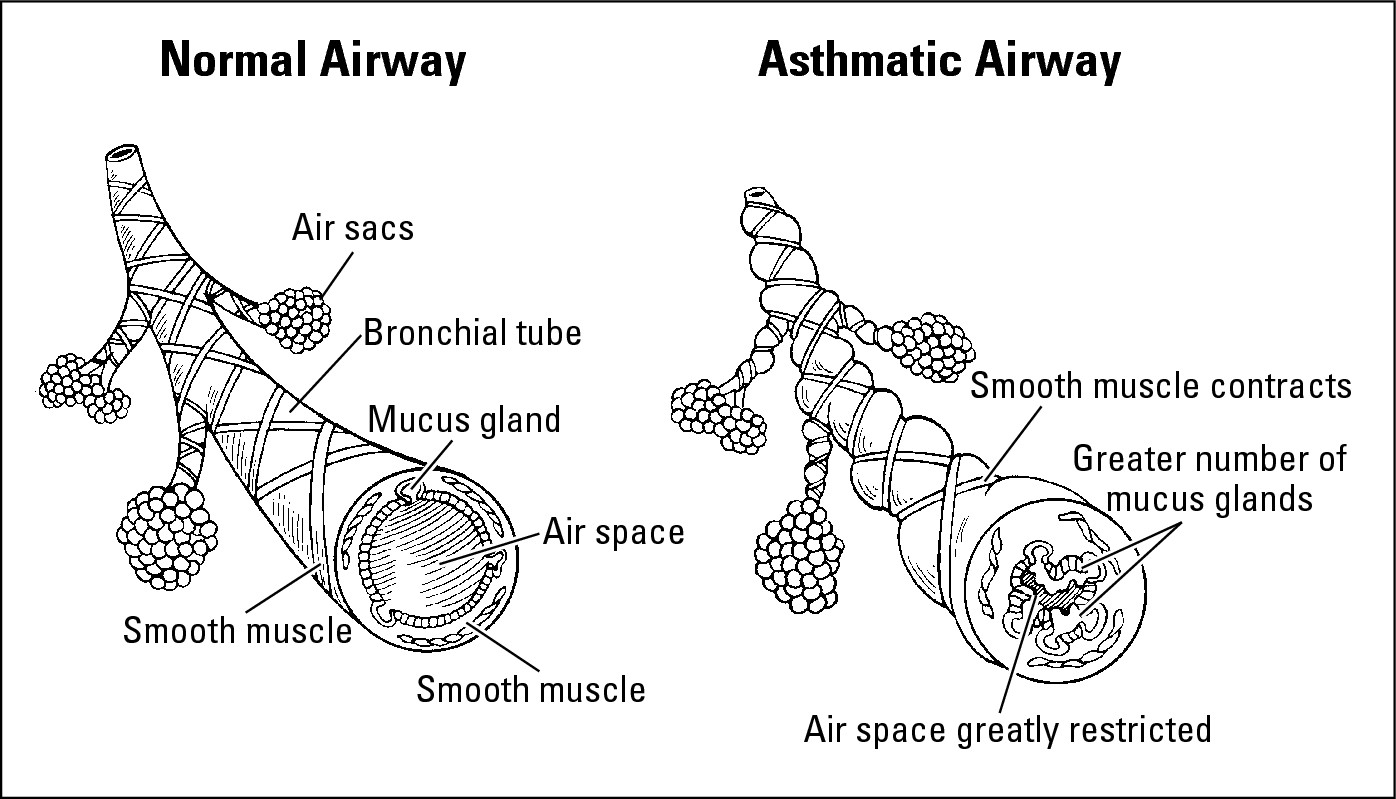

3. The main bronchi continue branching, like tree branches, within your lungs, dividing into a network of airways called bronchial tubes. The outside of your bronchial tubes consists of layers of smooth, involuntary muscles that relax and tighten your airways as you inhale and exhale. Doctors refer to the process of airway relaxation as bronchodilation. Likewise, doctors refer to the tightening, which helps your lungs push out air when you exhale, as bronchoconstriction.

4. Your network of airways ultimately leads to alveoli, tiny air sacs that look like small clusters of grapes. The alveoli contain blood vessels and provide the means for vital respiratory exchange: Oxygen from the air you inhale is absorbed into the bloodstream, while carbon dioxide gas from your blood exits as you exhale.

How airway obstruction develops

Airway constriction: When a trigger or precipitating factor irritates your airways, causing the release of chemical mediators such as histamine and leukotrienes (see Chapter 6) from the mast cells of the epithelium (the lining of the airway), the muscles around your bronchial tubes can tighten, leading to airway constriction. This process results in narrowing airways and breathing difficulty. Airway constriction can also occur in people who don’t have asthma or allergies if they’re exposed to substances that can harm their respiratory systems, such as poisonous gases or smoke from a burning building.

Airway constriction: When a trigger or precipitating factor irritates your airways, causing the release of chemical mediators such as histamine and leukotrienes (see Chapter 6) from the mast cells of the epithelium (the lining of the airway), the muscles around your bronchial tubes can tighten, leading to airway constriction. This process results in narrowing airways and breathing difficulty. Airway constriction can also occur in people who don’t have asthma or allergies if they’re exposed to substances that can harm their respiratory systems, such as poisonous gases or smoke from a burning building.

Airway hyperresponsiveness: The underlying airway inflammation in asthma can cause airway hyperresponsiveness as the muscles around your bronchial tubes twitch or feel ticklish. This twitchy or ticklish feeling indicates that your muscles overreact and tighten, causing acute bronchoconstriction or bronchospasms even if you’re exposed only to otherwise harmless substances, such as allergens and irritants, that rarely provoke reactions in people without asthma and allergies (see the section “Uncovering the Many Facets of Asthma,” earlier in the chapter).

Airway hyperresponsiveness: The underlying airway inflammation in asthma can cause airway hyperresponsiveness as the muscles around your bronchial tubes twitch or feel ticklish. This twitchy or ticklish feeling indicates that your muscles overreact and tighten, causing acute bronchoconstriction or bronchospasms even if you’re exposed only to otherwise harmless substances, such as allergens and irritants, that rarely provoke reactions in people without asthma and allergies (see the section “Uncovering the Many Facets of Asthma,” earlier in the chapter).

|

Figure 2-1: A normal airway and an asthmatic airway. Note the muscle contractions (broncho-spasms) and airway inflam-mation. |

|

Airway congestion: Mucus and fluids are released as part of the inflammatory process and can accumulate in your airways, overwhelming the cilia (tiny hair-like projections from certain cells that sweep debris-laden mucus through your airways) and leading to airway congestion. This accumulation of mucus and fluids may make you feel the urge to cough up phlegm to relieve your chest congestion.

Airway congestion: Mucus and fluids are released as part of the inflammatory process and can accumulate in your airways, overwhelming the cilia (tiny hair-like projections from certain cells that sweep debris-laden mucus through your airways) and leading to airway congestion. This accumulation of mucus and fluids may make you feel the urge to cough up phlegm to relieve your chest congestion.

Airway edema: The long-term release of inflammatory fluids in constricted, hyperresponsive, and congested airways can lead to airway edema (swelling of the airway), causing bronchial tubes to become more rigid and further interfering with airflow. In severe cases of airway congestion and edema, a chronic buildup of mucus secretion leads to the formation of mucus plugs in the airway, which limit airflow.

Airway edema: The long-term release of inflammatory fluids in constricted, hyperresponsive, and congested airways can lead to airway edema (swelling of the airway), causing bronchial tubes to become more rigid and further interfering with airflow. In severe cases of airway congestion and edema, a chronic buildup of mucus secretion leads to the formation of mucus plugs in the airway, which limit airflow.

Airway remodeling: If airway inflammation is left untreated or poorly managed for many years, the constant injury to your bronchial tubes due to ongoing airway constriction, airway hyperresponsiveness, and airway congestion can lead to airway remodeling, as scar tissue permanently replaces your normal airway tissue. As a result of airway remodeling, airway obstruction can persist and may not respond to treatment, leading to the eventual loss of your airway function as well as potentially irreversible lung damage.

Airway remodeling: If airway inflammation is left untreated or poorly managed for many years, the constant injury to your bronchial tubes due to ongoing airway constriction, airway hyperresponsiveness, and airway congestion can lead to airway remodeling, as scar tissue permanently replaces your normal airway tissue. As a result of airway remodeling, airway obstruction can persist and may not respond to treatment, leading to the eventual loss of your airway function as well as potentially irreversible lung damage.

Diagnosing Asthma

Effectively managing your asthma begins with your doctor correctly diagnosing your condition. In order to determine whether asthma causes your respiratory symptoms, your doctor should take your medical history, perform a physical exam, test your lung functions, and perform other tests, as I explain in the following sections.

You experience episodes of airway obstruction.

You experience episodes of airway obstruction.

Your airway obstruction is at least partially reversible (and can be improved through treatment).

Your airway obstruction is at least partially reversible (and can be improved through treatment).

Your symptoms result from asthma, not from other conditions that I describe in “Considering other possible diagnoses,” later in this chapter.

Your symptoms result from asthma, not from other conditions that I describe in “Considering other possible diagnoses,” later in this chapter.

Taking your medical history

The type of symptoms you experience, which may include coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and productive coughs (coughs that bring up mucus).

The type of symptoms you experience, which may include coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and productive coughs (coughs that bring up mucus).

The pattern of your symptoms:

The pattern of your symptoms:

• Perennial (year-round), seasonal, or perennial with seasonal worsening

• Constant, episodic, or constant with episodic worsening

The onset of your symptoms. At what rate do your symptoms develop — rapidly or slowly? And does that rate vary?

The onset of your symptoms. At what rate do your symptoms develop — rapidly or slowly? And does that rate vary?

The duration and frequency of your symptoms and whether the type and intensity of symptoms vary at different times of day and night. Especially note if your episodes awaken you from sleep or are more severe when you wake up in the morning.

The duration and frequency of your symptoms and whether the type and intensity of symptoms vary at different times of day and night. Especially note if your episodes awaken you from sleep or are more severe when you wake up in the morning.

The impact that exercise or other physical exertion has on your symptoms.

The impact that exercise or other physical exertion has on your symptoms.

Your exposure to potential asthma triggers. In addition to the allergens, irritants, and precipitating factors that I list in the section “Uncovering the Many Facets of Asthma,” earlier in this chapter, your doctor also needs to know about endocrine factors, such as adrenal or thyroid disease. Special considerations for women are pregnancy or changes in their menstrual cycles.

Your exposure to potential asthma triggers. In addition to the allergens, irritants, and precipitating factors that I list in the section “Uncovering the Many Facets of Asthma,” earlier in this chapter, your doctor also needs to know about endocrine factors, such as adrenal or thyroid disease. Special considerations for women are pregnancy or changes in their menstrual cycles.

The development of your disease, including any prior treatment and medications you’ve received or taken and their effectiveness. Your doctor particularly wants to know whether you presently take or have previously taken oral corticosteroids and, if so, the dosage and frequency of use.

The development of your disease, including any prior treatment and medications you’ve received or taken and their effectiveness. Your doctor particularly wants to know whether you presently take or have previously taken oral corticosteroids and, if so, the dosage and frequency of use.

Your family history, especially whether parents, siblings, or close relatives suffer from asthma, allergic or nonallergic rhinitis, and other types of allergies, sinusitis, or nasal polyps.

Your family history, especially whether parents, siblings, or close relatives suffer from asthma, allergic or nonallergic rhinitis, and other types of allergies, sinusitis, or nasal polyps.

Your lifestyle, including

Your lifestyle, including

• Your home’s characteristics, such as its age and location, type of cooling and heating system, your basement’s condition, whether you have a wood-burning stove, humidifier, carpet over concrete, mold and mildew, and the types of bedding, carpeting, and furniture coverings that you use.

• Whether anyone smokes in your home or the other locations where you spend time, such as work or school.

• Any history of substance abuse.

The impact of the disease on you and your family, such as

The impact of the disease on you and your family, such as

• Any life-threatening symptoms, emergency or urgent care treatments, or hospitalizations.

• The number of days you (or your child with asthma) tend to miss from school or work, the disease’s economic impact, and its effect on your recreational activities.

• If your child has asthma, your doctor may ask you about the effects of the illness on your youngster’s growth, development, behavior, and extent of participation in sports.

Your knowledge, perception, and beliefs about asthma and long-term management of the disease, as well as your ability to cope with the illness.

Your knowledge, perception, and beliefs about asthma and long-term management of the disease, as well as your ability to cope with the illness.

The level of support you receive from your family members and their abilities to recognize and assist you in case your symptoms suddenly worsen.

The level of support you receive from your family members and their abilities to recognize and assist you in case your symptoms suddenly worsen.

Examining your condition

A physical exam for suspected asthma usually focuses not only on your breathing passageways, but also on other characteristics and symptoms of atopic disease. The significant physical signs of asthma or allergy that your doctor looks for primarily include

Chest deformity, such as an expanded or overinflated chest, as well as hunched shoulders

Chest deformity, such as an expanded or overinflated chest, as well as hunched shoulders

Coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, and other respiratory symptoms

Coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, and other respiratory symptoms

Increased nasal discharge, swelling, and the presence of nasal polyps

Increased nasal discharge, swelling, and the presence of nasal polyps

Signs of sinus disease, such as thick or discolored nasal discharge

Signs of sinus disease, such as thick or discolored nasal discharge

Any allergic skin conditions, such as atopic dermatitis (eczema — in Chapter 1, I explain how this ailment and asthma can often be connected)

Any allergic skin conditions, such as atopic dermatitis (eczema — in Chapter 1, I explain how this ailment and asthma can often be connected)

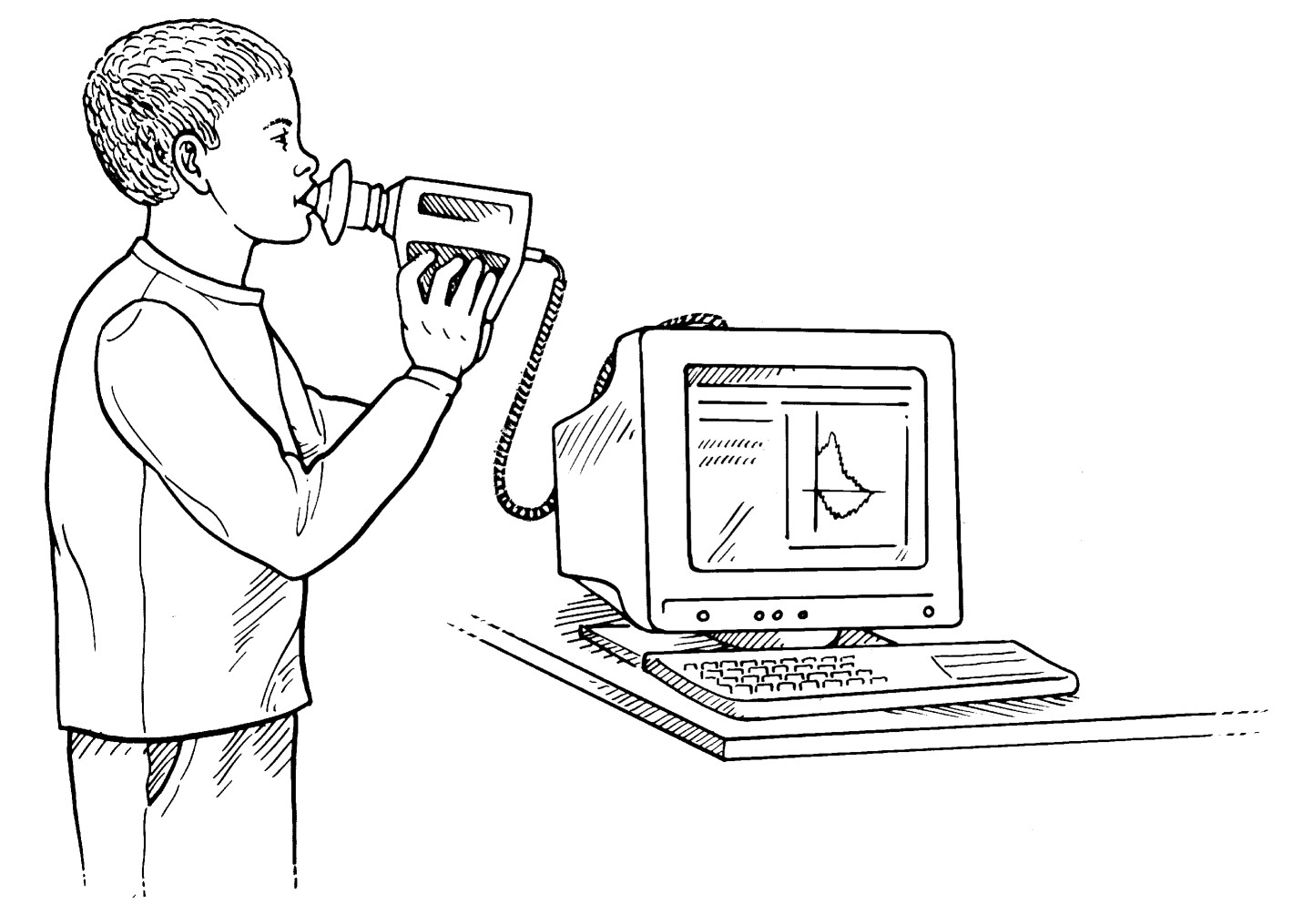

Testing your lungs

Objective pulmonary function tests are the most reliable means of assessing the extent to which your lung function is limited or affected. The following sections explain the most important tests that doctors use to diagnose asthma. (See Chapter 4 for a more detailed description of these tests.)

Spirometry

|

Figure 2-2: A spirom-eter measures airflow. |

|

Forced vital capacity (FVC): The maximum volume (in liters) of air that you can exhale after taking in as deep a breath as you can.

Forced vital capacity (FVC): The maximum volume (in liters) of air that you can exhale after taking in as deep a breath as you can.

Forced expiratory volume (FEV1): The volume (in liters) of air that you’re able to exhale when you breathe out with maximal effort in the first second, as forcefully as possible. Physicians determine a reduction in FEV1 as the most common indicator of airway obstruction and in patients with symptoms of asthma. This test, the most important measurement in the diagnosis and management of asthma, generally measures obstruction of the large airways, although FEV1 can also reveal severe obstruction, if present, of the small airways. A baseline FEV1 (before using a bronchodilator) that is lower than normal but that increases by at least 12 percent 15 minutes after inhaling a short-acting bronchodilator (post-bronchodilator) allows your doctor to more conclusively establish the diagnosis of asthma.

Forced expiratory volume (FEV1): The volume (in liters) of air that you’re able to exhale when you breathe out with maximal effort in the first second, as forcefully as possible. Physicians determine a reduction in FEV1 as the most common indicator of airway obstruction and in patients with symptoms of asthma. This test, the most important measurement in the diagnosis and management of asthma, generally measures obstruction of the large airways, although FEV1 can also reveal severe obstruction, if present, of the small airways. A baseline FEV1 (before using a bronchodilator) that is lower than normal but that increases by at least 12 percent 15 minutes after inhaling a short-acting bronchodilator (post-bronchodilator) allows your doctor to more conclusively establish the diagnosis of asthma.

Maximum midexpiratory flow rate (MMEF): The middle part of your forced exhalation (in liters per second). This measurement is also referred to as the forced expiratory flow rate between 25 and 75 percent (FEF 25–75 percent) of FVC. A reduction in this measurement can indicate obstruction of the lungs’ small airways.

Maximum midexpiratory flow rate (MMEF): The middle part of your forced exhalation (in liters per second). This measurement is also referred to as the forced expiratory flow rate between 25 and 75 percent (FEF 25–75 percent) of FVC. A reduction in this measurement can indicate obstruction of the lungs’ small airways.

Your doctor compares the values from the spirometry to the predicted normal reference values, based on your age, height, sex, and race, as established by the American Thoracic Society. The percent of the predicted normal value of your measured FEV1 is one of the major criteria your doctor uses to classify your level of asthma severity. (See Chapter 4 for information on the four levels of asthma severity.)

The jaws of asthma

Picture one of those scary shark movies: People swim about peacefully on the ocean surface until suddenly, a fin breaks the waves (cue the ominous double basses and cellos) and a shark attacks a hapless swimmer. The shark doesn’t just materialize out of nowhere; it’s been lurking around underwater, probably for a long time. But the swimmers on the surface don’t notice it until it’s too late.

Your asthma episodes are similar to that shark attack (without the bite marks). If you rely only on short-acting inhaled beta 2 -adrenergic bronchodilators — known as rescue medications — to treat your asthma symptoms when they flare up, that’s the equivalent of swimming in shark-infested waters, hoping that someone rescues you if the creature comes after you.

I constantly advise my patients (and you, throughout this book) to manage their asthma on a consistent, long-term preventive basis and to avoid a crisis-management approach. (The section “Managing Your Asthma: Essential Steps,” later in this chapter, provides you with more details.) You can control your asthma; don’t let your asthma control you!

Peak-flow meters

Just as diabetics check their blood sugar levels with a monitoring device and people with hypertension take their own blood pressure, you can also keep an eye on your lung functions at home with a peak-flow meter. Peak-flow meters, which are available in a variety of shapes and sizes from different manufacturers (see the appendix), are convenient, portable, and easy-to-use devices for monitoring peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR), the maximum rate of air (in liters per minute) that you can force out of your large airways, as a measurement of lung function.

This measurement isn’t as accurate as spirometry, but you can easily perform it at home. Measurements of PEFR are also a vital part of long-term management of your asthma, as I explain in more depth in Chapter 4.

Challenge tests

If spirometry indicates normal or near-normal lung functions but asthma continues to seem the most likely cause of your symptoms, your doctor may decide that a form of challenge test is necessary for a more conclusive diagnosis.

Challenge tests, also called bronchoprovocation, usually involve your doctor administering small doses of inhaled methacholine or histamine to you or making you exercise under his observation. The goal of such tests is to see whether these challenges cause obstructive changes in your airways, thus provoking mild asthma symptoms. Your doctor usually measures your lung functions before and after each test.

Considering other possible diagnoses

An upper respiratory disease, such as allergic rhinitis or sinusitis

An upper respiratory disease, such as allergic rhinitis or sinusitis

A swallowing mechanism problem or the effects of GERD

A swallowing mechanism problem or the effects of GERD

Congenital heart disease, often leading to congestive heart failure

Congenital heart disease, often leading to congestive heart failure

An obstruction of large airways, possibly caused by

An obstruction of large airways, possibly caused by

• A foreign object in the trachea or main bronchi, such as a small piece of popcorn that your child may have accidentally inhaled

• Problems of the larynx (the cartilaginous portion of the upper respiratory tract that contains the vocal cords) or with the vocal cords themselves

• Benign or malignant tumors or enlarged lymph nodes

An obstruction of the small airways, as a result of

An obstruction of the small airways, as a result of

• Cystic fibrosis

• Abnormal development of the bronchi and lungs

• Viral infection of the bronchioles (small bronchi)

With adult cases, underlying problems may include

Chronic bronchitis and/or emphysema, collectively referred to as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Chronic bronchitis and/or emphysema, collectively referred to as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Pulmonary embolism (a blood clot, air bubble, bacteria mass, or other mass that can clog a blood vessel)

Pulmonary embolism (a blood clot, air bubble, bacteria mass, or other mass that can clog a blood vessel)

Heart disease

Heart disease

Problems of the vocal cords or the larynx (vocal cord dysfunction)

Problems of the vocal cords or the larynx (vocal cord dysfunction)

Benign or malignant tumors in the airways

Benign or malignant tumors in the airways

A cough reaction due to drugs such as ACE inhibitors that you may be using to treat other conditions, such as hypertension

A cough reaction due to drugs such as ACE inhibitors that you may be using to treat other conditions, such as hypertension

Classifying asthma severity

If your doctor diagnoses you with asthma based on your medical history, the physical exam, and appropriate tests, studies, and assessments, he also needs to define your condition’s severity. Physicians classify asthma — whether allergic or nonallergic — according to four levels of severity.

Experts from different fields of medicine have developed these severity classifications, which provide the basis for “stepwise” management of asthma. I explain stepwise management and asthma severity levels in detail in Chapter 4.

Referring to a specialist for diagnosis

Your diagnosis is difficult to establish.

Your diagnosis is difficult to establish.

Your diagnosis requires specialized testing, such as allergy testing (see Chapter 11), bronchoprovocation (see the section “Testing your lungs,” earlier in this chapter), or bronchoscopy (an exam of the interior of your bronchi using a slender, flexible fiber-optic bronchoscope).

Your diagnosis requires specialized testing, such as allergy testing (see Chapter 11), bronchoprovocation (see the section “Testing your lungs,” earlier in this chapter), or bronchoscopy (an exam of the interior of your bronchi using a slender, flexible fiber-optic bronchoscope).

Your doctor advises you to consider allergy shots; see Chapter 11.

Your doctor advises you to consider allergy shots; see Chapter 11.

Other conditions, such as sinusitis, nasal polyps, severe rhinitis, GERD, chronic bronchitis and/or emphysema (COPD), vocal cord problems, or aspergillosis (a fungal infection that can affect the lungs), complicate your condition or diagnosis.

Other conditions, such as sinusitis, nasal polyps, severe rhinitis, GERD, chronic bronchitis and/or emphysema (COPD), vocal cord problems, or aspergillosis (a fungal infection that can affect the lungs), complicate your condition or diagnosis.

You don’t seem to be doing as well as you’d like.

You don’t seem to be doing as well as you’d like.

You aren’t able to regularly sleep through the night without being awakened by your asthma.

You aren’t able to regularly sleep through the night without being awakened by your asthma.

You can’t exercise as you’d like to because of asthma.

You can’t exercise as you’d like to because of asthma.

You need to use an asthma inhaler for quick relief on a daily basis or in the middle of the night.

You need to use an asthma inhaler for quick relief on a daily basis or in the middle of the night.

You’ve experienced a previous emergency room visit or hospitalization for asthma (see Chapter 5) or anaphylaxis (see Chapter 1).

You’ve experienced a previous emergency room visit or hospitalization for asthma (see Chapter 5) or anaphylaxis (see Chapter 1).

Managing Your Asthma: Essential Steps

Going over the basics

Your asthma management plan requires your full participation in order to work most effectively. One of the most important ways for you to actively participate in your asthma treatment is to find out about not only the disease’s complexities, but also medications, self-monitoring, allergies, triggers, and precipitating factors.

Assessment and monitoring of your lung functions: In addition to helping diagnose asthma, certain tests and assessments are vital in tracking how your condition develops and responds to prescribed treatment. See the section “Testing your lungs,” earlier in the chapter, and Chapter 4 for more information.

Assessment and monitoring of your lung functions: In addition to helping diagnose asthma, certain tests and assessments are vital in tracking how your condition develops and responds to prescribed treatment. See the section “Testing your lungs,” earlier in the chapter, and Chapter 4 for more information.

Avoidance measures: Ways of avoiding and controlling your exposure to asthma triggers and precipitating factors.

Avoidance measures: Ways of avoiding and controlling your exposure to asthma triggers and precipitating factors.

Medication: Using appropriate medication to prevent symptoms if you’re exposed to allergens, irritants, and other asthma triggers.

Medication: Using appropriate medication to prevent symptoms if you’re exposed to allergens, irritants, and other asthma triggers.

• Long-term pharmacotherapy: This involves using medications to prevent symptoms by treating the underlying airway inflammation, congestion, constriction, and hyperresponsiveness.

• Short-term pharmacotherapy: This involves using fast-acting rescue medications when your condition suddenly deteriorates.

Knowing when an

attack is serious: This is based on frequency of rescue inhaler use, decrease in peak-flow values, and increased nighttime awakenings.

Knowing when an

attack is serious: This is based on frequency of rescue inhaler use, decrease in peak-flow values, and increased nighttime awakenings.

Determining what to do if you have a serious attack: You should know how to adjust your medication in response to a worsening of symptoms and when to call for medical help if your condition continues to deteriorate.

Determining what to do if you have a serious attack: You should know how to adjust your medication in response to a worsening of symptoms and when to call for medical help if your condition continues to deteriorate.

An ongoing process of education for you and your family about asthma: This process can involve information and resources that your doctor, clinic staff, and patient support groups provide or recommend, as well as relevant books, newsletters, videos, and other helpful materials that you and your family gather.

An ongoing process of education for you and your family about asthma: This process can involve information and resources that your doctor, clinic staff, and patient support groups provide or recommend, as well as relevant books, newsletters, videos, and other helpful materials that you and your family gather.

Determining your asthma therapy goals

Other results that you should expect from asthma therapy include

Preventing chronic and troublesome symptoms of asthma, such as coughing, shortness of breath, wheezing (especially upon awakening in the morning), and episodes that disturb your sleep at night

Preventing chronic and troublesome symptoms of asthma, such as coughing, shortness of breath, wheezing (especially upon awakening in the morning), and episodes that disturb your sleep at night

Preventing recurring aggravation of symptoms

Preventing recurring aggravation of symptoms

Minimizing the need for emergency care and hospitalization

Minimizing the need for emergency care and hospitalization

Providing the most effective medication therapy that results in minimal or no adverse side effects

Providing the most effective medication therapy that results in minimal or no adverse side effects

You’ve suffered a life-threatening asthma attack.

You’ve suffered a life-threatening asthma attack.

You’re not meeting the goals of your asthma therapy.

You’re not meeting the goals of your asthma therapy.

You require more education and guidance on possible treatment complications, the avoidance and control of triggers and precipitating factors, and your asthma management program.

You require more education and guidance on possible treatment complications, the avoidance and control of triggers and precipitating factors, and your asthma management program.

You have severe persistent asthma that requires constant daily use of preventive medications and frequent use of short-acting inhaled beta

2

-adrenergic (beta

2

-agonist) bronchodilators.

You have severe persistent asthma that requires constant daily use of preventive medications and frequent use of short-acting inhaled beta

2

-adrenergic (beta

2

-agonist) bronchodilators.

Your condition requires continuous use of oral corticosteroids, high-dose inhaled corticosteroids, or more than two bursts of oral corticosteroids within one year.

Your condition requires continuous use of oral corticosteroids, high-dose inhaled corticosteroids, or more than two bursts of oral corticosteroids within one year.

You have a child under age 3 who has moderate persistent or severe persistent asthma (see Chapter 4) and requires constant use of preventive medication and frequent use of short-acting inhaled beta

2

-adrenergic bronchodilators.

You have a child under age 3 who has moderate persistent or severe persistent asthma (see Chapter 4) and requires constant use of preventive medication and frequent use of short-acting inhaled beta

2

-adrenergic bronchodilators.

You care for a person with asthma who experiences significant psychological, emotional, or family problems that interfere with or prevent that person from following an appropriate asthma management plan. Such experiences can lead to worsening asthma symptoms, which pose a threat to the patient’s health. In this event, have him or her undergo an evaluation by a mental health professional.

You care for a person with asthma who experiences significant psychological, emotional, or family problems that interfere with or prevent that person from following an appropriate asthma management plan. Such experiences can lead to worsening asthma symptoms, which pose a threat to the patient’s health. In this event, have him or her undergo an evaluation by a mental health professional.

Handling emergencies

Give you a written action plan that you can follow in case your condition deteriorates. Children with asthma need a plan that they can use at school, daycare, or summer camp. Your written action plan must clearly instruct you on how to adjust your medications in response to particular signs, symptoms, and PEFR levels, as well as tell you when to call for medical help.

Give you a written action plan that you can follow in case your condition deteriorates. Children with asthma need a plan that they can use at school, daycare, or summer camp. Your written action plan must clearly instruct you on how to adjust your medications in response to particular signs, symptoms, and PEFR levels, as well as tell you when to call for medical help.

Instruct you to seek medical help early if your episode is severe, if medication doesn’t provide rapid, sustained improvement, or if your condition continues to deteriorate.

Instruct you to seek medical help early if your episode is severe, if medication doesn’t provide rapid, sustained improvement, or if your condition continues to deteriorate.

Advise you to keep on hand appropriate medications, peak-flow meters, and inhalant devices, such as nebulizers, to treat severe episodes at home if you suffer from moderate-to-severe persistent asthma or have a history of severe asthma attacks.

Advise you to keep on hand appropriate medications, peak-flow meters, and inhalant devices, such as nebulizers, to treat severe episodes at home if you suffer from moderate-to-severe persistent asthma or have a history of severe asthma attacks.

Warn you against trying to manage severe episodes with home remedies, such as drinking large amounts of water, breathing steam or moist air (from a hot shower), taking OTC medications such as antihistamines, cold and flu remedies, and pain relievers, or using OTC bronchodilators. Although these types of inhalers can sometimes provide temporary relief of airway constriction, they certainly aren’t the preferable approach when appropriate medical care is required for treating acute asthma emergencies. (See Chapter 15 for information on effective use of asthma controller medications.)

Warn you against trying to manage severe episodes with home remedies, such as drinking large amounts of water, breathing steam or moist air (from a hot shower), taking OTC medications such as antihistamines, cold and flu remedies, and pain relievers, or using OTC bronchodilators. Although these types of inhalers can sometimes provide temporary relief of airway constriction, they certainly aren’t the preferable approach when appropriate medical care is required for treating acute asthma emergencies. (See Chapter 15 for information on effective use of asthma controller medications.)

Managing asthma at school

Meet with school staff to inform them about any medications that your child may need to take while on campus, as well as any physical activity restrictions that your doctor may advise. (With proper management of their conditions, most children with asthma can participate in sports and physical education classes.)

Meet with school staff to inform them about any medications that your child may need to take while on campus, as well as any physical activity restrictions that your doctor may advise. (With proper management of their conditions, most children with asthma can participate in sports and physical education classes.)

File treatment authorization forms with the school office and discuss what school personnel need to do in case of an asthma emergency. Provide phone numbers and other avenues for school personnel to reach you and your child’s physician in the event of an emergency.

File treatment authorization forms with the school office and discuss what school personnel need to do in case of an asthma emergency. Provide phone numbers and other avenues for school personnel to reach you and your child’s physician in the event of an emergency.

Inform school personnel of allergens and irritants that can trigger your child’s asthma symptoms and request that the school remove the sources of those triggers if possible.

Inform school personnel of allergens and irritants that can trigger your child’s asthma symptoms and request that the school remove the sources of those triggers if possible.

For more information on managing childhood asthma, turn to Chapter 18.