Chapter 4

Managing Asthma Long-Term

In This Chapter

Understanding what long-term asthma management involves

Understanding what long-term asthma management involves

Identifying the four levels of asthma severity

Identifying the four levels of asthma severity

Taking the stepwise approach to treatment

Taking the stepwise approach to treatment

Evaluating your lungs

Evaluating your lungs

Figuring out self-management

Figuring out self-management

Enhancing your life and overall health

Enhancing your life and overall health

R ather than letting your asthma control you, the key to controlling your asthma is to treat it on a consistent and preventive basis. Doing so means managing your asthma for the long term, rather than dealing with symptoms and episodes only temporarily. Developing and sticking to a long-term asthma management strategy is a priceless investment in your overall health and quality of life, especially if you have persistent asthma. The fundamental point is to address the root cause of your symptoms — the underlying airway inflammation that characterizes asthma.

Seeing What a Long-Term Management Plan Includes

A comprehensive long-term management plan for persistent asthma should include the following elements:

Objective testing and monitoring of your lung functions to initially diagnose your condition and to continuously assess the effectiveness of your treatment (see Chapter 2 and the sections “Assessing Your Lungs” and “Taking Stock of Your Condition,” later in this chapter, for more information).

Objective testing and monitoring of your lung functions to initially diagnose your condition and to continuously assess the effectiveness of your treatment (see Chapter 2 and the sections “Assessing Your Lungs” and “Taking Stock of Your Condition,” later in this chapter, for more information).

Avoiding and controlling exposures to asthma triggers and precipitating factors (see Chapter 5).

Avoiding and controlling exposures to asthma triggers and precipitating factors (see Chapter 5).

Developing a safe and effective pharmacotherapy program that results in minimal or no adverse side effects. The program includes taking appropriate long-term preventive medications on a routine basis to control your asthma and using appropriate short-term, quick-relief rescue medications if your symptoms suddenly get worse (see Chapter 16).

Developing a safe and effective pharmacotherapy program that results in minimal or no adverse side effects. The program includes taking appropriate long-term preventive medications on a routine basis to control your asthma and using appropriate short-term, quick-relief rescue medications if your symptoms suddenly get worse (see Chapter 16).

Initiating pharmacotherapy with a stepwise (step-up or step-down) approach. (See the “Using the Stepwise Approach” section, later in this chapter, for details.)

Initiating pharmacotherapy with a stepwise (step-up or step-down) approach. (See the “Using the Stepwise Approach” section, later in this chapter, for details.)

Consulting with an asthma specialist, such as an allergist or pulmonologist (lung doctor), when advisable (see Chapter 2).

Consulting with an asthma specialist, such as an allergist or pulmonologist (lung doctor), when advisable (see Chapter 2).

Tailoring your asthma management plan to your specific circumstances and condition and continuing education for you and your family about asthma and your specific condition (see “Understanding Self-Management,” later in this chapter).

Tailoring your asthma management plan to your specific circumstances and condition and continuing education for you and your family about asthma and your specific condition (see “Understanding Self-Management,” later in this chapter).

“Outgrowing” your asthma: Fact or fiction

Asthma isn’t something that you usually outgrow. Extensive studies over the past 15 years have shown that asthma is an ongoing physical condition that doesn’t just disappear forever when you feel better. Your asthma can vary in its symptoms and severity during your lifetime. However, just like the color of your eyes or your individual fingerprint pattern, when you have asthma, it remains as another of your distinctive, although unseen, physical characteristics.

When you have asthma, the airways of your lungs get bigger as you grow, so mild airway obstruction may not affect you as much as you get older. Also, as you mature, your sensitivities may not be sufficient to cause clinical symptoms that you notice. However, people who feel that they “outgrew” their asthma as children or teenagers commonly experience symptoms of the disease later in life, particularly in response to certain triggers (see Chapter 5 for more on asthma triggers).

Focusing on the Four Levels of Asthma Severity

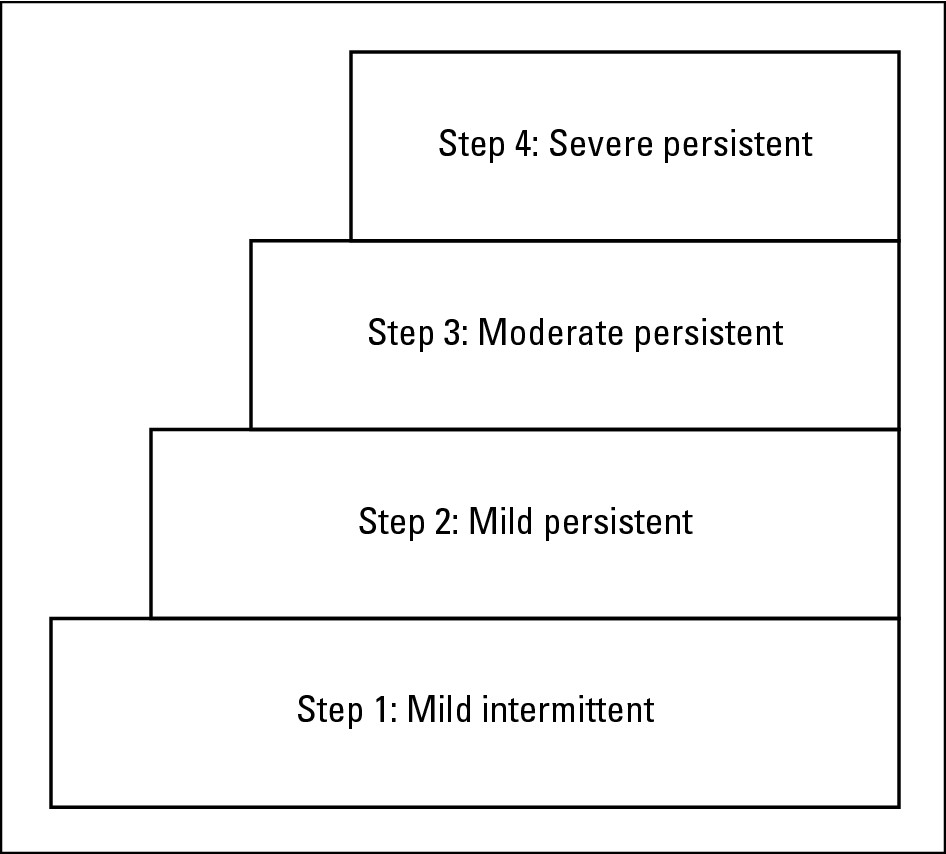

Experts from different fields of medicine have classified the severity of asthma — whether allergic or nonallergic — into four levels. These asthma severity levels provide the basis for the stepwise management of the disease.

As described in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma, the four levels of asthma severity are

Mild intermittent. Symptoms occur no more than twice a week during the day and no more than twice a month at night. Lung-function testing (see Chapter 2) shows 80 percent or greater of the predicted normal value, compared to reference values based on your age, height, sex, and race, as established by the American Thoracic Society. In addition, your peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR; see Chapter 2) shouldn’t vary by more than 20 percent during episodes and from the morning to the evening. Between episodes, you may be asymptomatic (not have noticeable symptoms), and your PEFR should be normal. If your asthma is at this level, a worsening of symptoms is usually brief, lasting a few hours to a few days, with variations of intensity.

Mild intermittent. Symptoms occur no more than twice a week during the day and no more than twice a month at night. Lung-function testing (see Chapter 2) shows 80 percent or greater of the predicted normal value, compared to reference values based on your age, height, sex, and race, as established by the American Thoracic Society. In addition, your peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR; see Chapter 2) shouldn’t vary by more than 20 percent during episodes and from the morning to the evening. Between episodes, you may be asymptomatic (not have noticeable symptoms), and your PEFR should be normal. If your asthma is at this level, a worsening of symptoms is usually brief, lasting a few hours to a few days, with variations of intensity.

Mild persistent. Symptoms occur more than twice a week during the day, but less than once a day, and more than twice a month at night. Lung-function testing shows 80 percent or greater of the predicted normal value. Your PEFR may vary between 20 and 30 percent. If your asthma is at this level of severity, then worsening of symptoms can begin to affect your activities.

Mild persistent. Symptoms occur more than twice a week during the day, but less than once a day, and more than twice a month at night. Lung-function testing shows 80 percent or greater of the predicted normal value. Your PEFR may vary between 20 and 30 percent. If your asthma is at this level of severity, then worsening of symptoms can begin to affect your activities.

Moderate persistent. Symptoms occur daily and more than once a week at night, requiring daily use of a short-acting bronchodilator. Lung-function testing shows a 60 to 80 percent range of the normal predicted value. Your PEFR can vary more than 30 percent. Symptoms can worsen at least twice a week, with episodes lasting for days and affecting your activities.

Moderate persistent. Symptoms occur daily and more than once a week at night, requiring daily use of a short-acting bronchodilator. Lung-function testing shows a 60 to 80 percent range of the normal predicted value. Your PEFR can vary more than 30 percent. Symptoms can worsen at least twice a week, with episodes lasting for days and affecting your activities.

Severe persistent. Symptoms occur continuously during the day and frequently at night, limiting physical activity. Lung-function testing is 60 percent or less of the normal predicted value. Your PEFR may vary more than 30 percent, and frequent aggravations of your condition can develop.

Severe persistent. Symptoms occur continuously during the day and frequently at night, limiting physical activity. Lung-function testing is 60 percent or less of the normal predicted value. Your PEFR may vary more than 30 percent, and frequent aggravations of your condition can develop.

Using the Stepwise Approach

Asthma severity levels are steps in the staircase to controlling asthma, as shown in Figure 4-1. The basic concept of stepwise management is to initially prescribe long-term and quick-relief medications, based on the severity level that’s one step higher than the severity level you’re experiencing (see Table 4-1). By using this approach, your doctor can usually help you gain rapid control over your symptoms. After your condition has been under control for a month (in most cases), your physician can reduce the level of your medications by one level (step down ).

|

Figure 4-1: The steps of asthma severity levels. |

|

The information in Table 4-1 is based on the NIH Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Please remember that these are guidelines. Your doctor should always evaluate your own specific condition and prescribe individualized treatment accordingly.

| Step | Long-Term Control | Quick Relief |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Mild | No daily medication | Short-acting bronchodilator: |

| intermittent | needed | Inhaled beta2-adrenergics as |

| needed for symptoms. Intensity | ||

| of treatment may vary depend | ||

| ing on the severity of your | ||

| symptoms. (If you’re using a | ||

| short-acting inhaled beta2- | ||

| adrenergics more than twice a | ||

| week, you may need to initiate | ||

| long-term control therapy. | ||

| Consult your doctor in this | ||

| case.) | ||

| Step 2: Mild | One daily medication: | Short-acting bronchodilator: |

| persistent | Anti-inflammatory medic- | Inhaled beta2-adrenergics as |

| ation, either inhaled corti- | needed for symptoms. Intensity | |

| costeroid (low dose) or | of treatment may vary depend | |

| mast cell stabilizers, such | ing on the severity of your | |

| as cromolyn or nedocromil. | symptoms. (If you’re using a | |

| Your doctor may also con- | short-acting inhaled beta2- | |

| sider anti-leukotriene mod- | adrenergics more than twice a | |

| ifiers such as zafirlukast | week, you may need additional | |

| and montelukast. Your | long-term control therapy. | |

| physician may also con- | Consult your doctor in | |

| sider a methylxanthine | this case.) | |

| product such as sustained- | ||

| release theophylline as an | ||

| alternative treatment, but | ||

| not as preferred therapy. | ||

| Step 3*: Moderate | Daily medication: Anti- | Short-acting bronchodilator: |

| persistent | inflammatory medication, | Inhaled beta2-adrenergics as |

| inhaled corticosteroid | needed for symptoms. | |

| (medium dose), or inhaled cor- | Intensity of treatment may vary | |

| ticosteroid (low to medium | depending on the severity of | |

| dose), adding a long-acting | your symptoms. (If you’re using | |

| bronchodilator, especially for | a short-acting inhaled beta2- | |

| nighttime symptoms — either | adrenergic more than twice a | |

| long-acting inhaled beta2- | week, you may need additional | |

| adrenergics, sustained | long-term control therapy. | |

| release theophylline, or long- | Consult your doctor in this | |

| acting beta2-adrenergic | case.) | |

| tablets. | ||

| If needed: Anti-inflammatory | ||

| medication, inhaled corticos- | ||

| teroid (medium-high dose), | ||

| and long-acting bronchodila- | ||

| tor, especially for nighttime | ||

| symptoms — either long- | ||

| acting inhaled beta2- | ||

| adrenergics, sustained | ||

| release theophylline, or long- | ||

| acting beta2-adrenergic tablets. | ||

| Step 4*: Severe | Daily medication: Anti- | Short-acting bronchodilator: |

| persistent | inflammatory medication, | Inhaled beta2-adrenergics as |

| inhaled corticosteroid (high | needed for symptoms. Intensity | |

| dose), and long-acting bron- | of treatment may vary depend | |

| chodilator — either long- | ing on the severity of your | |

| acting inhaled beta2- | symptoms. (If you’re using a | |

| adrenergics, sustained | short-acting inhaled beta2- | |

| release theophylline, or long- | adrenergic more than twice a | |

| acting beta2-adrenergic | week, you may need additional | |

| tablets; and if required, long- | long-term control therapy. | |

| term use of corticosteroid | Consult your doctor in this | |

| tablets or syrup. | case.) |

*If your asthma severity is at Step 3 or Step 4, consult an asthma specialist, such as an allergist or pulmonologist (lung doctor), to achieve better control of your condition.

Stepping down

If you’re on long-term maintenance control at any level, your doctor should review your treatment every one to six months. A gradual stepwise reduction in treatment may be possible after your symptoms are under good control, meaning that you feel good, have maintained improved lung function, and experience no asthma symptoms.

Stepping up

Your inhaler technique. (See “Evaluating your inhaler technique,” later in this chapter.)

Your inhaler technique. (See “Evaluating your inhaler technique,” later in this chapter.)

Your level of adherence in taking the medications that your doctor prescribes.

Your level of adherence in taking the medications that your doctor prescribes.

Your exposure level to asthma triggers, such as allergens and irritants and precipitating factors, such as viral infections and other medical conditions. Control your exposure to asthma triggers and precipitating factors as much as possible, no matter what step of treatment you’re receiving. (See Chapter 5 for information on controlling asthma triggers.)

Your exposure level to asthma triggers, such as allergens and irritants and precipitating factors, such as viral infections and other medical conditions. Control your exposure to asthma triggers and precipitating factors as much as possible, no matter what step of treatment you’re receiving. (See Chapter 5 for information on controlling asthma triggers.)

Make sure that your asthma management plan clearly explains at what point you should contact your physician if your symptoms worsen.

Treating severe episodes in stepwise management

Your doctor may consider prescribing a rescue course of oral corticosteroids at any step if you suddenly experience a severe asthma episode and your condition abruptly deteriorates. (Chapter 16 provides more information on oral corticosteroids.)

.jpg)

Assessing Your Lungs

Objective measurements of your lung functions are essential for monitoring your asthma’s severity. Just as you check the oil level in your car on a regular basis (rather than waiting for the flashing red warning light), you and your doctor should also regularly check your airways to determine whether you’re at the right step of asthma medication. In addition to recording your asthma symptoms in a daily symptom diary (see “Keeping symptom records,” later in this chapter), you should also obtain objective measurements of lung functions with spirometry and peak-flow monitoring.

What your doctor should do: Spirometry

For adults and children older than age 4 or 5, spirometry currently provides the most accurate way of determining whether airway obstruction exists and whether it’s reversible. For information on other types of lung-function tests your doctor may recommend and to find out more about diagnosing asthma in children under age 4, see Chapter 2.

What you can do: Peak-flow monitoring

Peak-flow meters (see Figure 4-2) allow you to keep an eye on your lung functions at home. The readings from this handy tool can be vital in diagnosing asthma and its severity and can also help your doctor prescribe medications and monitor your treatment’s effectiveness. Peak-flow monitoring can also provide important early warning signs that an asthma episode is approaching.

|

Figure 4-2: A patient using a peak-flow meter. |

|

Explaining and using peak-flow meters for children

By the same token, when your child’s PEFR is between 80 to 100 percent of his or her personal best, you can breathe easier about encouraging sports and other physical activities that are vital aspects of improving their overall health and fitness, including their lung functions. Make sure, however, that you and your child know how to manage potential symptoms of exercise-induced asthma (EIA), as I explain in Chapter 18.

Using a peak-flow meter at home

Generally, you use a peak-flow meter by following these steps:

1. Move the sliding indicator at the base of the peak-flow meter to zero.

2. Stand up and take a deep breath to fully inflate your lungs.

3. Put the mouthpiece of the peak-flow meter into your mouth and close your lips tightly around it.

4. Blow as hard and as fast as possible, like you’re blowing out the candles on your birthday cake.

5. Read the dial where the red indicator stopped. The number opposite the indicator is your peak-flow rate.

6. Reset the indicator to zero and repeat the process twice more.

7. Record the highest number that you reach.

Finding your personal best peak-flow number

Your personal best peak-flow number is a measurement that reflects the highest number you can expect to achieve over a two- to three-week period after a course of aggressive treatment has produced good control of your asthma symptoms. Your best number is usually the result of step-up therapy.

.jpg)

Reading green, yellow, and red peak-flow color zones

The peak-flow zone system involves green, yellow, and red areas, which are similar to a traffic signal. Using your peak-flow meter on a regular basis enables you and your doctor to treat symptoms before your condition deteriorates further.

Table 4-2 explains how to read the peak-flow color zones.

| Zone | Meaning | Points to Consider |

|---|---|---|

| Green zone | Readings in this area | When your reading falls into the |

| are safe. | green zone, you’ve achieved 80 to | |

| 100 percent of your personal best | ||

| peak flow. No asthma symptoms | ||

| are present, and your treatment | ||

| plan is controlling your asthma. If | ||

| your readings consistently remain | ||

| in the green zone, you and your | ||

| doctor may consider reducing | ||

| daily medications. | ||

| Yellow zone | Readings in this area | When your readings fall into the |

| indicate caution. | yellow zone, you’re achieving only | |

| 50 to 80 percent of your personal | ||

| best peak flow. An asthma attack | ||

| may be present, and your symp | ||

| toms may worsen. You may need | ||

| to step up your medication | ||

| temporarily. | ||

| Red zone | Readings in this area | Readings in the red zone mean |

| mean medical alert. | that you’ve fallen below 50 percent | |

| of your personal best peak flow. | ||

| These readings often signal the | ||

| start of a moderate to severe | ||

| asthma attack. |

Taking Stock of Your Condition

In addition to obtaining an objective measurement of your lung function with measuring devices, another important aspect of controlling your asthma is keeping track of a variety of other indicators. Your most valuable tracking device is usually a daily symptom diary. In fact, you should develop a rating system (in consultation with your doctor) for your diary that assesses your symptoms on a scale of 0 to 3, ranging from no symptoms to severe symptoms.

Keeping symptom records

Your signs and symptoms, as well as their severity

Your signs and symptoms, as well as their severity

Any coughing that you experience

Any coughing that you experience

Any incidence of wheezing

Any incidence of wheezing

Nasal congestion

Nasal congestion

Disturbances in your sleep, such as coughing and/or wheezing that awaken you

Disturbances in your sleep, such as coughing and/or wheezing that awaken you

Any symptoms that affect your ability to function normally or reduce normal activities

Any symptoms that affect your ability to function normally or reduce normal activities

Any time you miss school or work because of symptoms

Any time you miss school or work because of symptoms

Frequency of use of your short-acting beta

2

-adrenergic bronchodilator (rescue medication)

Frequency of use of your short-acting beta

2

-adrenergic bronchodilator (rescue medication)

Tracking serious symptoms

Be sure to record the following types of serious symptoms:

Breathlessness or panting while at rest

Breathlessness or panting while at rest

The need to remain in an upright position in order to breathe

The need to remain in an upright position in order to breathe

Difficulty speaking

Difficulty speaking

Agitation or confusion

Agitation or confusion

An increased breathing rate of more than 30 breaths per minute

An increased breathing rate of more than 30 breaths per minute

Loud wheezing while inhaling and/or exhaling

Loud wheezing while inhaling and/or exhaling

An elevated pulse rate of more than 120 heartbeats per minute

An elevated pulse rate of more than 120 heartbeats per minute

Irritants, such as chemicals or cigarette or fireplace smoke

Irritants, such as chemicals or cigarette or fireplace smoke

Allergens, such as plant pollen, household dust, molds, and animal fur

Allergens, such as plant pollen, household dust, molds, and animal fur

Air pollution

Air pollution

Exercise (Chapter 9 provides more information on exercise-induced asthma)

Exercise (Chapter 9 provides more information on exercise-induced asthma)

Sudden changes in the weather, particularly cold temperatures and chilly winds

Sudden changes in the weather, particularly cold temperatures and chilly winds

Reactions to beta-blockers (such as Inderal or Timoptic), aspirin, and related products, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and food additives — particularly sulfites (see Chapter 5)

Reactions to beta-blockers (such as Inderal or Timoptic), aspirin, and related products, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and food additives — particularly sulfites (see Chapter 5)

Other medical conditions, such as upper respiratory viral infections (colds and flu), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and sinusitis (see Chapter 5)

Other medical conditions, such as upper respiratory viral infections (colds and flu), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and sinusitis (see Chapter 5)

Monitoring your medication use

Evaluating your inhaler technique

Your doctor should show you the correct way to use your inhaler (see Chapter 15 for detailed instructions on using inhalers) and have you demonstrate your inhaler technique at each office visit. In the best of cases when using inhalers, only 10 to 20 percent of the topical inhaled drug gets into the areas of your lungs where it can really do some good. Because such small amounts of inhaler medications actually reach the airways of your lungs, understanding how to use your inhaler properly is vital to your treatment. Improper inhaler use is often the reason why some patients have difficulty controlling their asthma symptoms.

Understanding Self-Management

It takes two (at least) to treat asthma. You and your physician (as well as your other healthcare providers) are partners in controlling your asthma. Other members of your asthma partnership can include nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals who treat you or assist you in understanding and finding out more about effectively managing your condition.

If your child has asthma, you should also be a partner with your child’s doctor and other medical professionals in the management of your youngster’s condition. (Chapter 18 provides details on managing asthma in children.)

Working with your doctor

Making sure that your plan is tailored to your specific, individualized needs, as well as your family’s, is also very important. Doing so can include taking into account any cultural beliefs and practices that can have an impact on your perception of asthma and of medication therapy. Openly discuss any such issues with your physician, so that together, you can develop an approach to asthma management that empowers you to take control of your condition. Ensuring that your plan is tailored to fit you and your family results in a more motivated patient, which almost always means a healthier individual.

Evaluating for the long term

Successfully managing your asthma also means constantly assessing your asthma management plan to determine whether it provides you with the means to achieve your asthma management goals.

Becoming an expert about your asthma

Knowing the basic facts about asthma.

Knowing the basic facts about asthma.

Understanding the level of your asthma severity, how it affects you, and advisable treatment methods.

Understanding the level of your asthma severity, how it affects you, and advisable treatment methods.

Teaching you all the elements of asthma self-management, including basic facts about the disease and your specific condition, proper use of various inhalers and nebulizers, self-monitoring skills, and effective ways of avoiding triggers and allergy-proofing your home.

Teaching you all the elements of asthma self-management, including basic facts about the disease and your specific condition, proper use of various inhalers and nebulizers, self-monitoring skills, and effective ways of avoiding triggers and allergy-proofing your home.

Developing a written individualized daily and emergency self-management plan with your input (see Chapter 2).

Developing a written individualized daily and emergency self-management plan with your input (see Chapter 2).

Determining the level of support you receive from family and friends in treating your asthma. It’s also important for your doctor to help you identify an asthma partner from among your family members, relatives, or friends. This person should find out how asthma affects you and should understand your asthma management plan so that he or she can provide assistance (if necessary) if your condition suddenly worsens. I advise including your asthma partner in doctor visits when appropriate.

Determining the level of support you receive from family and friends in treating your asthma. It’s also important for your doctor to help you identify an asthma partner from among your family members, relatives, or friends. This person should find out how asthma affects you and should understand your asthma management plan so that he or she can provide assistance (if necessary) if your condition suddenly worsens. I advise including your asthma partner in doctor visits when appropriate.

Asking your doctor and/or other members of your asthma management team for guidance in setting priorities when implementing your asthma management plan. If you need to make environmental changes in your life, such as allergy-proofing your home (which may include relocating a pet, taking up the carpets, installing air filtration devices, and many other steps that I explain in Chapter 5), you may want advice on which steps you need to take soonest and which steps can wait.

Asking your doctor and/or other members of your asthma management team for guidance in setting priorities when implementing your asthma management plan. If you need to make environmental changes in your life, such as allergy-proofing your home (which may include relocating a pet, taking up the carpets, installing air filtration devices, and many other steps that I explain in Chapter 5), you may want advice on which steps you need to take soonest and which steps can wait.

Improving Your Quality of Life

Taking asthma medication doesn’t mean that you can afford to ignore other aspects of your health. Effectively managing your asthma for the long term also requires being healthy overall. The better you take care of yourself, the more success you’ll have in treating your asthma and living a full, normal life.

Consider these important, common-sense guidelines when developing an asthma management plan:

Eating right. A healthy, well-balanced diet is especially important for people who have asthma. Include fresh fruits, meats, fish, grains, and vegetables in your diet.

Eating right. A healthy, well-balanced diet is especially important for people who have asthma. Include fresh fruits, meats, fish, grains, and vegetables in your diet.

Sleeping well. If you experience asthma symptoms during the night that disturb your sleep, tell your doctor. These types of symptoms should be treated, and they may indicate that you’re susceptible to precipitating factors, such as GERD, or asthma triggers such as dust mites in your bedroom (see Chapter 5).

Sleeping well. If you experience asthma symptoms during the night that disturb your sleep, tell your doctor. These types of symptoms should be treated, and they may indicate that you’re susceptible to precipitating factors, such as GERD, or asthma triggers such as dust mites in your bedroom (see Chapter 5).

Reducing stress. By effectively controlling your asthma, you’ll feel less anxious about your condition, thus reducing the overall levels of stress in your life and further helping you manage your asthma.

Reducing stress. By effectively controlling your asthma, you’ll feel less anxious about your condition, thus reducing the overall levels of stress in your life and further helping you manage your asthma.

Expecting the Best

If, as sometimes happens, your doctor deals only with your asthma symptoms — instead of initiating the type of long-term approach that I discuss in this chapter — you may want to consider requesting a referral to an asthma specialist. Expect to effectively control your asthma, and your doctor should certainly help you achieve this goal.