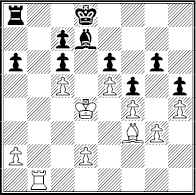

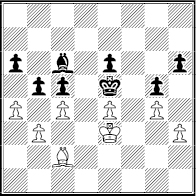

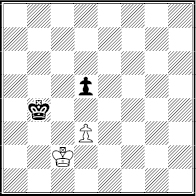

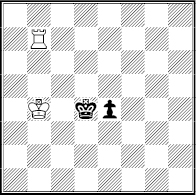

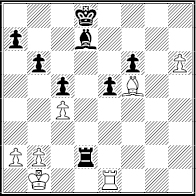

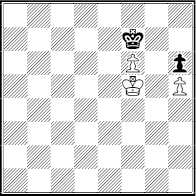

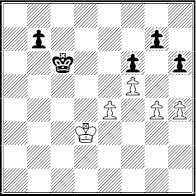

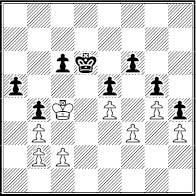

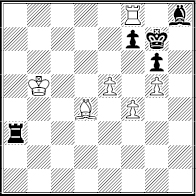

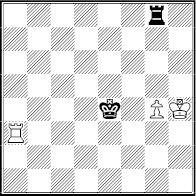

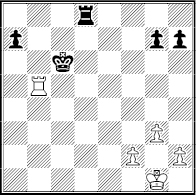

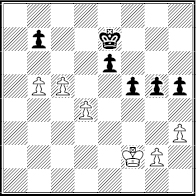

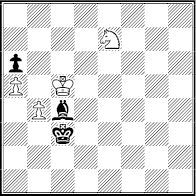

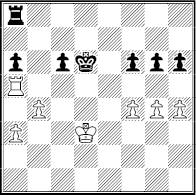

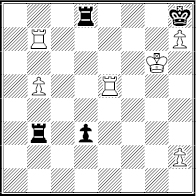

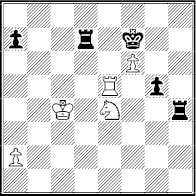

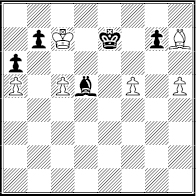

Cosma – Schut

Istanbul 2012

White to play

Mastering the endgame means acquiring two very different kinds of know-how. The most important are techniques. These are the recurring devices that enable you to win favorable endings and draw unfavorable ones.

You already know many of these techniques. Everyone who takes chess seriously has won endgames with zugzwang, even if he or she can’t pronounce it. You can’t win K+R-vs.-K without zugzwang.

Other techniques are more subtle and remain the trade secrets of masters. In this chapter we’ll examine 25 of the most essential.

In most endgames, you must penetrate an enemy defense to win. Even with a significant positional or material edge, you can fail to win because you are simply locked out.

Cosma – Schut

Istanbul 2012

White to play

White has a vastly superior bishop, better pawns and control of the only open file. But there is no way for her king or rook to penetrate.

Black can defend indefinitely with ‘pass’ moves like …  c8-d8. After 20 moves of fruitless maneuvering, White agreed to a draw.

c8-d8. After 20 moves of fruitless maneuvering, White agreed to a draw.

To become a master you need to know how to create an entry for yourself – and how to deny one to an opponent.

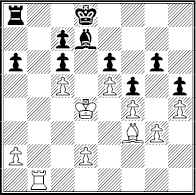

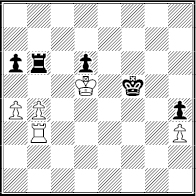

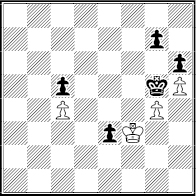

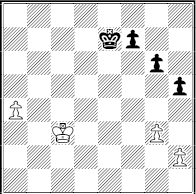

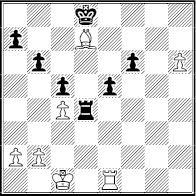

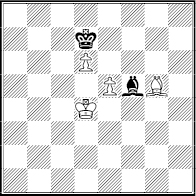

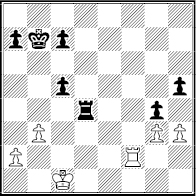

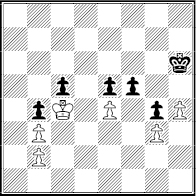

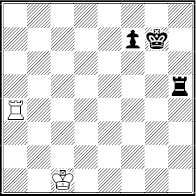

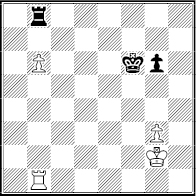

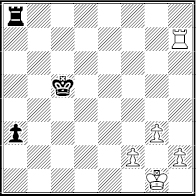

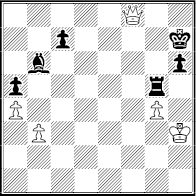

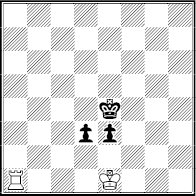

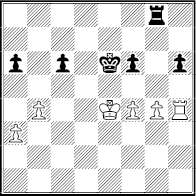

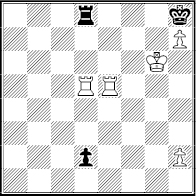

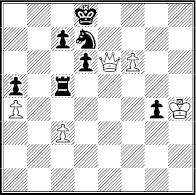

Kengis – Yuneev

Daugavpils 1989

Black to play

White’s king can’t get through the center. His best winning chance lies on the kingside. But Black can shut the door with 1 … h5!.

White could still try to win, through zugzwang – 2  b3

b3  b7 3 a5 bxa5 4

b7 3 a5 bxa5 4  a3!.

a3!.

That would be rewarded by 4 …  b6?? 5

b6?? 5  a4! and 6

a4! and 6  xa5. But if Black is alert he can draw with 4 …

xa5. But if Black is alert he can draw with 4 …  a7 5

a7 5  a4

a4  b6.

b6.

Instead of this, Black blundered with 1 …  b7??. That allowed White to create an entry with 2 h5! gxh5 3

b7??. That allowed White to create an entry with 2 h5! gxh5 3  d3.

d3.

His plan was  e3-f3-g2-h3-h4xh5 and the eventual win of the f- or h-pawn.

e3-f3-g2-h3-h4xh5 and the eventual win of the f- or h-pawn.

If Black’s king runs to the kingside, 3 …  c7 4

c7 4  e3

e3  d6 5

d6 5  f3

f3  e6 6

e6 6  g2

g2  f6, he allows White to queen on the abandoned queenside, 7 a5! bxa5 8 b6.

f6, he allows White to queen on the abandoned queenside, 7 a5! bxa5 8 b6.

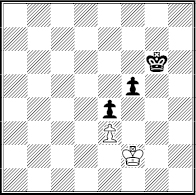

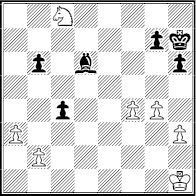

Black thought he could recover with 3 … h4!.

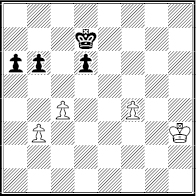

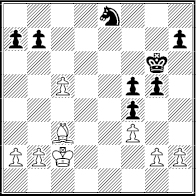

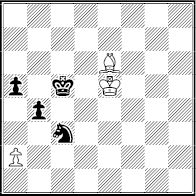

White to play

Then 4 gxh4 h5! would seal the kingside. But White won with 4  e3!.

e3!.

He needed an entry, not extra pawns, e.g. 4 … hxg3 5  f3

f3  c7 6

c7 6  xg3

xg3  d6 7

d6 7  h4

h4  e6 8

e6 8  g5 and White wins.

g5 and White wins.

Entry is needed in all sorts of endings, with rooks, knights, you name it. In the next example, with bishops, White is worse because all of his pawns are on light squares. He would lose if Black’s king or bishop penetrates the queenside.

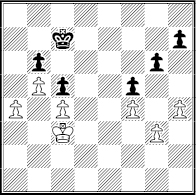

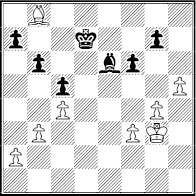

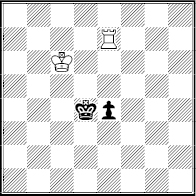

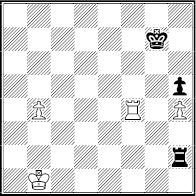

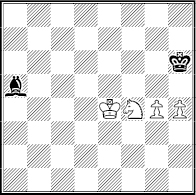

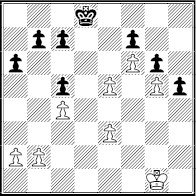

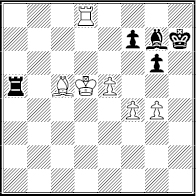

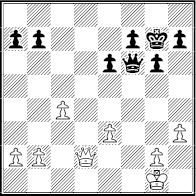

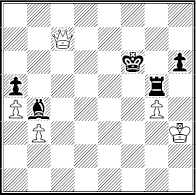

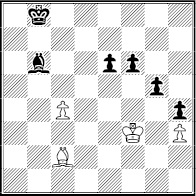

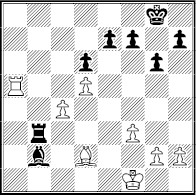

de Firmian – Benjamin

US Championship 1998

White to play

For example, 1 axb5 axb5 and 2 cxb5  xb5 threatens a winning …

xb5 threatens a winning …  f1. White is also lost after 2

f1. White is also lost after 2  f3

f3  d4!.

d4!.

White could pass with 2  d3. But then 2 … bxc4 3 bxc4

d3. But then 2 … bxc4 3 bxc4  a4! invades and wins – 4

a4! invades and wins – 4  b1

b1  b3 5

b3 5  d3

d3  a2 6

a2 6  e2

e2  b1. (White can draw with 3

b1. (White can draw with 3  xc4

xc4  xe4 4

xe4 4  xe6!

xe6!  g2 5

g2 5  c4.)

c4.)

Nevertheless White drew with the simple 1 a5!. Black’s king can’t penetrate via b6 and his bishop can’t get out via a4. No progress was possible, as 1 … bxc4 2 bxc4  e8 3

e8 3  d1

d1  c6 4

c6 4  c2

c2  a8 5

a8 5  d3

d3  b7 etc. showed.

b7 etc. showed.

In the middlegame with lots of material, players readily shift their pieces from one wing to the other as they attack and defend. But in an ending, the battles are often separated. A few pieces may face off on the kingside, a few on the queenside.

This means that a player can win if he can create a 2-to-1 mismatch on one of the wings.

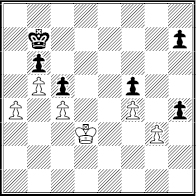

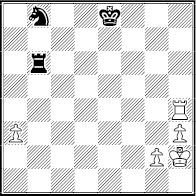

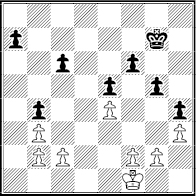

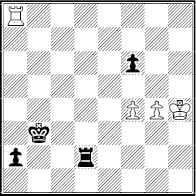

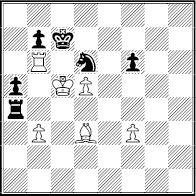

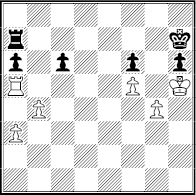

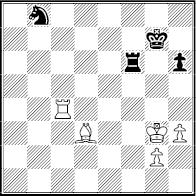

Gurgenidze – Radev

Tbilisi 1971

White to play

Rooks belong behind passed pawns – except when they don’t. Despite White’s rook he can’t make easy progress after 1 b5 axb5 2 axb5  f6 3

f6 3  b4?

b4?  g5.

g5.

More accurate was 1  f3+!

f3+!  g5 2

g5 2  c4. Black’s king is useless on the kingside because it cannot attack the rook or h-pawn.

c4. Black’s king is useless on the kingside because it cannot attack the rook or h-pawn.

But White has a K+P-vs.-R mismatch on the queenside. He threatens 3 b5 axb5+ 4 axb5 followed by  b4-a5 and the winning push of the pawn.

b4-a5 and the winning push of the pawn.

Black tried 2 …  c6+ 3

c6+ 3  b3 and saw that 3 …

b3 and saw that 3 …  b6 would fail to 4 b5! axb5 5 a5 followed by

b6 would fail to 4 b5! axb5 5 a5 followed by  b4. Instead, he chose 3 …

b4. Instead, he chose 3 …  c1 and lost after 4 b5 axb5 5 axb5 d5 6

c1 and lost after 4 b5 axb5 5 axb5 d5 6  d3! (6 …

d3! (6 …  c5 7

c5 7  b4).

b4).

Mismatches typically involve a king and pawn(s) versus a single piece. They are surprisingly strong against a lone rook and can usually out-muscle a lone bishop.

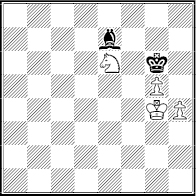

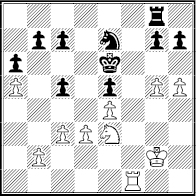

Geller – Kopylov

Soviet Championship 1951

White to play

Bishops of opposite color can make winning an ending difficult, time-consuming – or impossible. But in this case White won with 1  xa7!.

xa7!.

Black can trap the bishop with 1 …  c7. But after he wins it, 2 f4

c7. But after he wins it, 2 f4  b7 3

b7 3  xb6

xb6  xb6 4 g5, White has a K+Ps-vs.-B mismatch on the kingside.

xb6 4 g5, White has a K+Ps-vs.-B mismatch on the kingside.

Black would lose after 4 … fxg5 5 fxg5  f5 6

f5 6  f4

f4  h7 7

h7 7  e5 and

e5 and  e6-f7, for example, because his king can’t help the bishop (5 …

e6-f7, for example, because his king can’t help the bishop (5 …  c6 6

c6 6  f4

f4  d6 7 h6 gxh6 8 gxh6

d6 7 h6 gxh6 8 gxh6  g8 9

g8 9  f5 and

f5 and  g6).

g6).

Instead, he tried 4 …  f5 5 g6

f5 5 g6  c6 5

c6 5  h4

h4  e6 (or 5 …

e6 (or 5 …  d6 6 h6!). But he resigned after 6 h6! gxh6 7

d6 6 h6!). But he resigned after 6 h6! gxh6 7  h5

h5  d6 8

d6 8  xh6

xh6  e7 9 g7 when he realized he cannot defend both wings (9 …

e7 9 g7 when he realized he cannot defend both wings (9 …  g8 10

g8 10  g6

g6  e6 11 a4).

e6 11 a4).

Sometimes a simple trade of pieces will create a mismatch.

Tal – Ragozin

Soviet Championship 1956

Black to play

Black has good drawing chances if his knight and king reach the kingside (1 …  d7!). But he played 1 …

d7!). But he played 1 …  e7?? and White jumped at the chance to swap rooks, 2

e7?? and White jumped at the chance to swap rooks, 2  b4!

b4!  xb4 3 axb4.

xb4 3 axb4.

Black’s king can win the b-pawn, 3 …  d6 4 h4

d6 4 h4  c6 and …

c6 and …  b5. But by then White’s king and kingside pawns will beat the overmatched knight.

b5. But by then White’s king and kingside pawns will beat the overmatched knight.

Black saved time with 3 …  c6 4 b5

c6 4 b5  d4 5 b6

d4 5 b6  d7 6 h4

d7 6 h4  c6. But he was still lost on the kingside after 7 h5

c6. But he was still lost on the kingside after 7 h5  e6 8 h6

e6 8 h6  f8 9

f8 9  g3

g3  xb6 10

xb6 10  f4.

f4.

A knight versus a king and two connected pawns isn’t even close, as 10 …  c7 11

c7 11  f5

f5  d7 12

d7 12  f6

f6  e8 13

e8 13  g7 showed. Black insisted on playing out a lost pawn endgame, after 13 …

g7 showed. Black insisted on playing out a lost pawn endgame, after 13 …  e7 14 h7

e7 14 h7  xh7 15

xh7 15  xh7.

xh7.

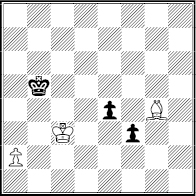

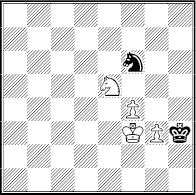

Some techniques can only be used to try to win. Others are useful only when defending. But the opposition can be invaluable in either case.

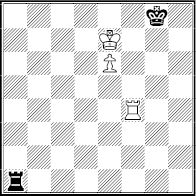

White to play

White can seize the opposition with 1  b2?. But Black regains it with 1 … d4! and reaches a winning position we’ll examine in Chapter Four (2

b2?. But Black regains it with 1 … d4! and reaches a winning position we’ll examine in Chapter Four (2  c2

c2  a3 3

a3 3  d2

d2  b2 4

b2 4  e2

e2  c2 and 5

c2 and 5  e1

e1  xd3 6

xd3 6  d1

d1  e3 7

e3 7  e1 d3 8

e1 d3 8  d1 d2 9

d1 d2 9  c2

c2  e2 is Exact Ending 1).

e2 is Exact Ending 1).

One way to draw is 1 d4!. Black wins the pawn but White gets the opposition after 1 …  c4 2

c4 2  d1

d1  xd4 3

xd4 3  d2!.

d2!.

He gets to another Exact Ending. But that one is a draw, e.g. 3 …  e4 4

e4 4  e2 d4 5

e2 d4 5  d2 d3 and 6

d2 d3 and 6  d1!

d1!  e3 7

e3 7  e1 d2+ 8

e1 d2+ 8  d1

d1  d3 stalemate. (By the way, 1

d3 stalemate. (By the way, 1  c1 draws in a similar way.)

c1 draws in a similar way.)

And here’s how the opposition is used to win.

Adams – Carlsen

London 2012

Black to play

Black must give way after 1 …  e6?? 2

e6?? 2  xe4 and loses. For example, 2 …

xe4 and loses. For example, 2 …  f6 3

f6 3  d5

d5  g5 4

g5 4  xc5

xc5  xg4 5

xg4 5  d5

d5  xh5 6 c5 and White queens first.

xh5 6 c5 and White queens first.

No better is 2 …  d6 3

d6 3  f5

f5  e7 4

e7 4  e5!, when White again has a winning opposition (4 …

e5!, when White again has a winning opposition (4 …  f7 5

f7 5  d5).

d5).

But the position in the diagram is actually a win for Black after 1 … e3!. He would have the opposition after 2  xe3

xe3  e5! (3

e5! (3  f3

f3  d4 or 3

d4 or 3  d3

d3  f4).

f4).

Instead, White tried the clever 2  f3!, hoping for 2 …

f3!, hoping for 2 …  e5?? 3

e5?? 3  xe3!, when he has stolen the opposition.

xe3!, when he has stolen the opposition.

But Black replied 2 …  e6! and 3

e6! and 3  e2

e2  f6. Then 4

f6. Then 4  xe3

xe3  e5! is that winning opposition once more.

e5! is that winning opposition once more.

White tried one last time, 4  f3. But Black had 4 …

f3. But Black had 4 …  g5!.

g5!.

White to play

White has run out of useful passes (5  g3 e2). He began the queening race with 5

g3 e2). He began the queening race with 5  xe3

xe3  xg4 6

xg4 6  e4

e4  xh5 7

xh5 7  d5. But Black is way ahead and won after 7 … g5 8

d5. But Black is way ahead and won after 7 … g5 8  xc5 g4 9

xc5 g4 9  d4 g3 10

d4 g3 10  e3

e3  g4.

g4.

‘Distant opposition’ sounds complex but just means that the kings are more than two squares apart. Then the right move is often easier to visualize than to calculate.

Timman – Yusupov

Amsterdam 1994

White to play

Natural moves like 1  g3? would lose, e.g. 1 …

g3? would lose, e.g. 1 …  g5 2

g5 2  h3 f4 3 exf4+

h3 f4 3 exf4+  xf4 4

xf4 4  g2

g2  e3 5

e3 5  f1

f1  d2 and … e3). Also 2

d2 and … e3). Also 2  f2

f2  h4! 3

h4! 3  g2

g2  g4 3

g4 3  f2

f2  h3.

h3.

White saw that Black’s king is on a light square. White just had to look for one near his own king. He played 1  g2! and then 1 …

g2! and then 1 …  g7 2

g7 2  g1!

g1!  f7 3

f7 3  f1

f1  e6 4

e6 4  e2.

e2.

Now on 4 …  d5 White cannot play the illegal 5

d5 White cannot play the illegal 5  d3. But he can draw after 5

d3. But he can draw after 5  d2

d2  c4 6

c4 6  c2, or, as the game went with 5 …

c2, or, as the game went with 5 …  d6 6

d6 6  d1

d1  c5 7

c5 7  c1! (7 …

c1! (7 …  b5 8

b5 8  b1

b1  a5 9

a5 9  c1).

c1).

This has been called the ‘hockey’ technique. One king stands in the way of the other king, like a hockey skater throwing a shoulder block.

This is particularly common after one player has been forced to give up his rook for a passed pawn and the result is a position like this:

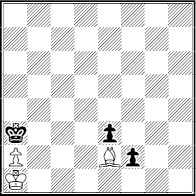

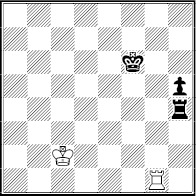

Liss – Lalic

Isle of Man 1997

White to play

The intuitive move is 1  e7. It succeeds after 1 … e4 2

e7. It succeeds after 1 … e4 2  b7

b7  f4 3

f4 3  c6 e3 4

c6 e3 4  d5

d5  f3 5

f3 5  d4 e2 6

d4 e2 6  d3. Black had to spend two moves – one by his king, one by his pawn – to safely advance the pawn one square.

d3. Black had to spend two moves – one by his king, one by his pawn – to safely advance the pawn one square.

Black can’t advance faster. But he can advance smarter, by meeting 1  e7? with 1 …

e7? with 1 …  e4! and 2

e4! and 2  b7

b7  d4!.

d4!.

The point is that Black’s king blocks the White king after 3  c6 e4.

c6 e4.

White to play

The draw is clear after 4  b5 e3 5

b5 e3 5  b4 and now 5 …

b4 and now 5 …  d3 6

d3 6  b3 e2.

b3 e2.

No better is 6  d7+ as long as Black finds 6 …

d7+ as long as Black finds 6 …  c2! (not 6 …

c2! (not 6 …  e2??, which blocks the pawn and allows a winning 7

e2??, which blocks the pawn and allows a winning 7  c3).

c3).

So let’s go back to the previous diagram and think up a better strategy for White. As slow as it seems, the correct way to start is 1  a7!.

a7!.

Then 1 … e4 2  b6 e3 3

b6 e3 3  e7!

e7!  f4 4

f4 4  c5 wins because Black never got a chance to throw a shoulder block.

c5 wins because Black never got a chance to throw a shoulder block.

But what if Black meets 1  a7 with 1 …

a7 with 1 …  e4, the move that beat 1

e4, the move that beat 1  e7 ? The answer is 2

e7 ? The answer is 2  b6!

b6!  d4 3

d4 3  b5 e4 4

b5 e4 4  b4!.

b4!.

Black to play

Now 4 … e3 5  d7+

d7+  e4 6

e4 6  c3 and White’s king gets to d2 in time to prevent promotion and win. Craftier is 4 …

c3 and White’s king gets to d2 in time to prevent promotion and win. Craftier is 4 …  d3! (5

d3! (5  d7+?

d7+?  c2). But 5

c2). But 5  b3! wins (5 … e3 6

b3! wins (5 … e3 6  d7+).

d7+).

Creating a passed pawn on the distant (‘outside’) wing of the board offers two ways to win:

Your opponent may not be close enough to stop it from queening.

Or, if he stops it, he may have to devote so much material to that task that he allows a mismatch on the other wing.

Fischer – Larsen

Candidates match 1971

White to play

White’s a-pawn is very ‘outside.’ But he cannot queen by force (1  b4

b4  d7 2

d7 2  b5

b5  c7 3 a5

c7 3 a5  b7 or 1 a5

b7 or 1 a5  d7 2 a6

d7 2 a6  c7).

c7).

White won by heading to the kingside while Black is torn between the two wings: 1  d4!

d4!  d6 2 a5.

d6 2 a5.

Then 2 … f6 – which stops  e5-f6 – was met by 3 a6!, threatening 4 a7. Black had to run to the queenside, 3 …

e5-f6 – was met by 3 a6!, threatening 4 a7. Black had to run to the queenside, 3 …  c6 4 a7

c6 4 a7  b7 5

b7 5  d5.

d5.

Black would lose after 5 …  xa7 6

xa7 6  e6. He tried to confuse matters with 5 … h4. White just ignored him and the game ended with 6

e6. He tried to confuse matters with 5 … h4. White just ignored him and the game ended with 6  e6 resigns in view of 6 … f5 7

e6 resigns in view of 6 … f5 7  f6 hxg3 8 hxg3 and

f6 hxg3 8 hxg3 and  xg6/

xg6/ xf5.

xf5.

Sometimes a potential outside pawn is hard to detect:

Stone – I. Ivanov

Dearborn 1992

Black to play

White has the most advanced pawn and it is passed. But the f-pawn can be stopped by Black’s king.

What decided the game was on the other wing: 1 … d5! 2 cxd5 a5!. Black created a passer that is seven files away from the helpless White king.

The game went 3  g4 b5 4 f5 a4 5 bxa4 bxa4 6 f6 a3 7 d6 and now not 7 … a2?? 8 f7! but simply 7 …

g4 b5 4 f5 a4 5 bxa4 bxa4 6 f6 a3 7 d6 and now not 7 … a2?? 8 f7! but simply 7 …  xd6 prompted resignation.

xd6 prompted resignation.

Black knew he was winning after he created a passed pawn in the last example because White’s king was ‘outside the square.’

Which square? It’s the one you can visualize with the Black pawn on a4. The square runs from a4 to a1, then to d1, to d4 and back to a4.

Even if White had played 3  g3 b5 4

g3 b5 4  f3 a4 5 bxa4 bxa4 he would be outside the square. Black would queen in three moves (5

f3 a4 5 bxa4 bxa4 he would be outside the square. Black would queen in three moves (5  e2 a3).

e2 a3).

This bit of elementary geometry is crucial when you can trade down to a pawn endgame:

Volokitin – Efimenko

Kharkov 2004

Black to play

White has executed a cutoff ( f4!), a potent technique we’ll consider shortly. Black’s king cannot cross the f-file to stop the b-pawn.

f4!), a potent technique we’ll consider shortly. Black’s king cannot cross the f-file to stop the b-pawn.

Black’s only hope was 1 …  g2! so that 2 b5?

g2! so that 2 b5?  g4!. That would work since White is outside the square (3

g4!. That would work since White is outside the square (3  xg4 hxg4 4

xg4 hxg4 4  c2 g3 5

c2 g3 5  d2?? g2).

d2?? g2).

He would have a choice of a drawn queen endgame (3  xg4 hxg4 4 b6 g3 5 b7 g2) or an equally drawn rook endgame (3

xg4 hxg4 4 b6 g3 5 b7 g2) or an equally drawn rook endgame (3  f5

f5  xh4 and …

xh4 and …  b4+).

b4+).

But White met 1 …  g2! with a simple precaution, 2

g2! with a simple precaution, 2  c1!. Then he was inside the square (2 …

c1!. Then he was inside the square (2 …  g4 3

g4 3  xg4 hxg4 4

xg4 hxg4 4  d2 g3 5

d2 g3 5  e2 g2 6

e2 g2 6  f2).

f2).

Black had no other tricks and played 2 …  a2 3 b5

a2 3 b5  a5. White relinquished the cutoff, 4

a5. White relinquished the cutoff, 4  b4!, because Black’s king is too far from the pawn.

b4!, because Black’s king is too far from the pawn.

The game went 4 …  f7 5 b6

f7 5 b6  a8 6 b7

a8 6 b7  b8 7

b8 7  d2 resigns, because White’s king will either reach c7 or win the h-pawn.

d2 resigns, because White’s king will either reach c7 or win the h-pawn.

If these examples of the square seem too easy, consider this case:

Kamsky – Karpov

Dortmund 1993

White to play

White can try 1  xd7 since 1 …

xd7 since 1 …  xd7 2

xd7 2  h1 (‘Rook behind the pawn’) makes his h-pawn a threat and wins. But this loses to 1 …

h1 (‘Rook behind the pawn’) makes his h-pawn a threat and wins. But this loses to 1 …  xd7 2

xd7 2  h1

h1  h7.

h7.

Instead, White played 1  g6?? and lost after 1 …

g6?? and lost after 1 …  h2 2 h7

h2 2 h7  e7.

e7.

Yet White should be playing for a win with 1  c1!. Then 1 …

c1!. Then 1 …  h2 loses to 2

h2 loses to 2  d1!. Or 1 …

d1!. Or 1 …  f2 2

f2 2  xd7 and 3

xd7 and 3  h1!.

h1!.

Best is 1 …  d4 but then comes 2

d4 but then comes 2  xd7.

xd7.

Black to play

Now both 2 …  xd7 and 2 …

xd7 and 2 …  xd7 lose to 3

xd7 lose to 3  d1!. After the rook trade, Black is outside the square. The best Black has is 2 …

d1!. After the rook trade, Black is outside the square. The best Black has is 2 …  xc4+ 3

xc4+ 3  b1

b1  h4 4

h4 4  d1, when White holds all the winning chances.

d1, when White holds all the winning chances.

Zugzwang sounds sophisticated. But anyone who has played rummy, contract bridge or one of several other card games knows what it’s like: It’s your turn to play a card but anything you do hurts your chances.

In chess, zugzwang can result from a move that seems to do nothing.

Sokolov – Sasikiran

Zafra 2007

White to play

White played 1  a1!. It doesn’t threaten a thing. But Black resigned. A king move allows 2

a1!. It doesn’t threaten a thing. But Black resigned. A king move allows 2  xf5. And a rook move (1 …

xf5. And a rook move (1 …  a5) allows 2

a5) allows 2  xf6+.

xf6+.

You often must rely on zugzwang when you have an edge in pieces – like having an extra Exchange – rather than in pawns.

The next position looks like it should be easy.

Anand – Topalov

Linares 2005

White to play

But after 1  d2 and 1 …

d2 and 1 …  b4 2

b4 2  e3

e3  a3 how can White make progress?

a3 how can White make progress?

He only has two pieces to perform three tasks. He needs to (a) capture the pawns, (b) stop … f2-f1( ) and (c) protect the a-pawn.

) and (c) protect the a-pawn.

For example, after 3  e6

e6  b4, 4

b4, 4  xe4 f2 5

xe4 f2 5  h3

h3  a3 and 6 …

a3 and 6 …  xa2 draws.

xa2 draws.

But White can win after 3 …  b4 with 4

b4 with 4  d5!

d5!  a3 5

a3 5  f2! – zugzwang. The win becomes obvious after 5 …

f2! – zugzwang. The win becomes obvious after 5 …  b4 6

b4 6  xe4 or 5 …

xe4 or 5 …  b2 6 a4.

b2 6 a4.

So, in the game Black played 1 … f2. He set a trap:

After 2  e2? e3! he draws (3

e2? e3! he draws (3  e6

e6  b4 4

b4 4  b3

b3  a3 5

a3 5  f1

f1  b4).

b4).

But White won with 2  e2+!

e2+!  b4 3

b4 3  c2!

c2!  a3 4

a3 4  b1 e3 5

b1 e3 5  a1.

a1.

Black to play

Black is again in zugzwang. He must allow the a-pawn to begin its march to a8, 5 …  a4 6

a4 6  b2

b2  b4 7 a3+

b4 7 a3+  a4 8

a4 8  a2! and White duly won.

a2! and White duly won.

Triangulation is a crooked path to zugzwang. It occurs when your opponent would be in zugzwang if it were his move. But it isn’t his turn.

White to play

If this were Black’s move, he loses, 1 …  e8 2

e8 2  g6

g6  f8 3 f7 or 3

f8 3 f7 or 3  xh6.

xh6.

But since it’s White’s turn, he has to lose a move. The way to do this is 1  e5

e5  f8 2

f8 2  e4!.

e4!.

Then 2 …  f7 3

f7 3  f5! recreates the position in the diagram but with Black to move. White accomplished this by moving his king in a triangle (e5-f4-f5) while Black’s king moved back and forth (f7-f8).

f5! recreates the position in the diagram but with Black to move. White accomplished this by moving his king in a triangle (e5-f4-f5) while Black’s king moved back and forth (f7-f8).

But suppose Black knows about opposition and plays 2 …  e8!.

e8!.

White would win with 3  f4

f4  f8! 4

f8! 4  e5. Black gives up the opposition and lands in the losing 4 …

e5. Black gives up the opposition and lands in the losing 4 …  f7 5

f7 5  f5! position or 4 …

f5! position or 4 …  e8 5

e8 5  e6

e6  f8 6 f7.

f8 6 f7.

Knowing how to triangulate allows you to force all sorts of simpler winning positions.

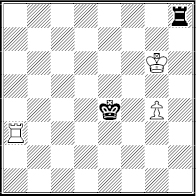

Dumitrake – Kiselev

Enakievo 1997

White to play

White played 1  h5! and 1 …

h5! and 1 …  xh5 2 gxh5. Black’s king is close enough to stop

xh5 2 gxh5. Black’s king is close enough to stop  g6xh6 with a shoulder block, 2 …

g6xh6 with a shoulder block, 2 …  e6!.

e6!.

But White forced his way to the previous diagram with 3  e4!

e4!  f6 4 f4!

f6 4 f4!  e6 5 f5+ and 5 …

e6 5 f5+ and 5 …  d6 6

d6 6  d4

d4  e7 7

e7 7  e5!

e5!  f7 8 f6.

f7 8 f6.

It’s this simple: The most common way to win an ending is to queen a pawn. Therefore, the most effective way to stop a pawn is to blockade it.

White to play

White has two extra, passed pawns near their queening squares. His winning chances? Zero.

Why? Because Black can hold his blockade at d7 and e6 forever.

This technique is so simple and powerful that every player with the advantage has to be careful about blundering into a blockade.

Vajda – Alekhine

Kecskemet 1927

Black to play

Black played 1 …  d8!, a good try in a lost position. White saw that 2 g5+?? allows 2 …

d8!, a good try in a lost position. White saw that 2 g5+?? allows 2 …  xg5, eliminating the last White pawns.

xg5, eliminating the last White pawns.

But he thought the position was an easy win after 2 h5??. He was shocked to find that Black can draw after 2 …  g5 or 2 …

g5 or 2 …  g5.

g5.

To win White had to take his time and avoid blockades. The right way is 2  g2!. Then 2 …

g2!. Then 2 …  xh4? 3

xh4? 3  xh4

xh4  g5 fails to 4

g5 fails to 4  f3

f3  xh4 5

xh4 5  f4 and wins.

f4 and wins.

Black’s only try is 2 …  g6. But then 3

g6. But then 3  f3

f3  h6 4

h6 4  g3

g3  c7+ 5

c7+ 5  f4 threatens 6 g5+/

f4 threatens 6 g5+/ g4 and leads to 5 …

g4 and leads to 5 …  d8 6

d8 6  e6

e6  e7 7 g5+

e7 7 g5+  g6 8

g6 8  g4.

g4.

Black to play

Only then does the win become easier, 8 …  h7 9

h7 9  f5!

f5!  g8 10

g8 10  g6

g6  h8 11

h8 11  f7. Or 9 …

f7. Or 9 …  h8! 10

h8! 10  g6

g6  g8 and then 11 h5

g8 and then 11 h5  xg5 12

xg5 12  xg5

xg5  h8 13

h8 13  f7+ and h5-h6-h7.

f7+ and h5-h6-h7.

In most cases, creating a passed pawn is routine. But in some, a dramatic technique – sacrificing a pawn or pawns – is necessary.

Averbakh – Bebchuk

Moscow 1964

White to play

Black has the outside passed pawn. Shouldn’t he be winning after 1  c4

c4  d6 2

d6 2  d4 b5 3

d4 b5 3  c3

c3  e5 ?

e5 ?

No. He loses: 1 e5! fxe5 2 g5! and 2 … hxg5 3 f6! gxf6 4 h5 and queens.

There is no salvation in 2 …  d6 because of 3 f6!

d6 because of 3 f6!  e6 4 fxg7

e6 4 fxg7  f7 5 gxh6 b5 6

f7 5 gxh6 b5 6  e4 b4 7

e4 b4 7  d3! and 8

d3! and 8  c4/9

c4/9  xb4 wins.

xb4 wins.

Breakthroughs occur most often in pawn endings. But they can have an equally surprising impact when other pieces are on the board.

Ivanchuk – Adams

Frankfurt 2000

White to play

White, a pawn down, can draw easily if he makes a cutoff, 1  f6!. Black’s king cannot easily advance and 1 …

f6!. Black’s king cannot easily advance and 1 …  d6 2

d6 2  f5! would cost a pawn.

f5! would cost a pawn.

But White tried to draw more quickly by using tactics. After 1 h3? he expected 1 … gxh3 2  h4 and 3

h4 and 3  xh3 would eliminate all kingside pawns.

xh3 would eliminate all kingside pawns.

That’s good logic but bad calculation. He overlooked 1 …  d4!. Then White would be outside the square after 2 hxg4

d4!. Then White would be outside the square after 2 hxg4  xf4 3 gxf4 h4!.

xf4 3 gxf4 h4!.

White played 2  f2, so that 2 … gxh3 3

f2, so that 2 … gxh3 3  h2 keeps his hopes alive.

h2 keeps his hopes alive.

Black to play

But this time he overlooked a breakthrough, 2 … h4!. That guarantees Black a strong passed pawn. For example, 3 gxh4 gxh3 followed by 4 …  xh4 5

xh4 5  h2

h2  c6 and the decisive entry of the Black king.

c6 and the decisive entry of the Black king.

White preferred 3 hxg4 but was lost after 3 … hxg3 4  g2

g2  xg4 5

xg4 5  d2

d2  c6 6

c6 6  e3

e3  b5.

b5.

A protected passed pawn is typically decisive in pawn endgames. It can often win piece endgames as well. But there is a way to offset it.

Michel – Euwe

Mar del Plata 1947

White to play

Black has just traded off all four rooks and appears assured of a win.

Why? Because he has an entry route, …  d7-e6 and …

d7-e6 and …  xe5.

xe5.

White’s king can defend the e-pawn – 1  f2

f2  d7 2

d7 2  f3

f3  e6 3

e6 3  f4. But the protected passed h-pawn pulls him away, 3 … h4 and 4 … h3 5

f4. But the protected passed h-pawn pulls him away, 3 … h4 and 4 … h3 5  g3

g3  xe5 6

xe5 6  xh3

xh3  e4, for example.

e4, for example.

Yet White was able to draw in the diagram and the outcome was clear after one move, 1 e6!. After the forced 1 … fxe6 he can just pass,  h2-g2-h2, if he wants.

h2-g2-h2, if he wants.

Black’s king cannot advance beyond the square of White’s protected f-pawn. He cannot create a passed queenside pawn either because … b5 would be answered by b2-b3!.

Creating a counter-passer is often a lot more complicated:

Aronin – Smyslov

Moscow 1951

White to play

White has just traded a rook and piece to reach what looks like an easy win. His king can reach c4 and begin picking off pawns. For example, 1  e2

e2  f7 2

f7 2  d3

d3  e6 3

e6 3  c4 a5 4

c4 a5 4  c5 and wins.

c5 and wins.

But Black would have counterplay after 1  e2

e2  g6 2

g6 2  d3 f5! and then 3 exf5+

d3 f5! and then 3 exf5+  xf5 4

xf5 4  c4 e4!.

c4 e4!.

Then White could win all the queenside pawns – and lose to a counter-passer, 5  xb4 e3! 6 fxe4

xb4 e3! 6 fxe4  e4 7

e4 7  c5

c5  xe3 8

xe3 8  xc6

xc6  f2 9 c4

f2 9 c4  xg2 and 10 … g4!.

xg2 and 10 … g4!.

So White found 1 g4!. That costs him a tempo, after 1 …  f7 2

f7 2  e2

e2  e6 3

e6 3  d3

d3  d6 4

d6 4  c4 a5. But White would win with 5 f3!, creating zugzwang:

c4 a5. But White would win with 5 f3!, creating zugzwang:

Black to play

For example, 5 …  d7 6

d7 6  c5

c5  c7 7 c3 bxc3 8 bxc3

c7 7 c3 bxc3 8 bxc3  d7 9

d7 9  b6. Or 8 …

b6. Or 8 …  b7 9

b7 9  d6

d6  b6 10 c4 and wins.

b6 10 c4 and wins.

All very logical. But after 1 g4 Black saved himself with the shocking 1 … hxg3! 2 fxg3 g4!.

His first idea is to create a kingside entry, 3 hxg4  g6 and …

g6 and …  g5xg4, to create a counter-passer. But this was doomed by 3 h4!. Black’s king could not leave the kingside.

g5xg4, to create a counter-passer. But this was doomed by 3 h4!. Black’s king could not leave the kingside.

But Black had a second point. After 3 … c5 4  e2

e2  h7 5

h7 5  d3

d3  h6 6 c3 a5 7 cxb4 axb4 it seemed like he was just passing aimlessly. But he was setting an ingenious trap. If White had continued 8

h6 6 c3 a5 7 cxb4 axb4 it seemed like he was just passing aimlessly. But he was setting an ingenious trap. If White had continued 8  c4 he would lose to 8 … f5!.

c4 he would lose to 8 … f5!.

White to play

White can’t stop the e-pawn after 9 exf5 e4 and he’s too late in creating is own counter-passer (10  xc5 e3).

xc5 e3).

Also lost is 9  d3 f4! 10 gxf4 exf4 11

d3 f4! 10 gxf4 exf4 11  e2

e2  h5 12 e5

h5 12 e5  g6! and …

g6! and …  f5xe5.

f5xe5.

So White backed off, didn’t play 8  c4?? and agreed to a draw.

c4?? and agreed to a draw.

One of the contradictions of endgame play is that it is often easier to win by reducing your material advantage.

Ponomariev – Sasikiran

Biel 2004

White to play

White has a choice of possible winning plans. He could try to advance his king to the vicinity of d7 or e6. Or he could try to isolate Black’s pawns (perhaps with f4-f5 and fxg6) so that they will be easier to attack.

But simpler and better was 1  d5! and then 1 …

d5! and then 1 …  e6 2

e6 2  xf6!. This converted to a pawn ending that was a routine win.

xf6!. This converted to a pawn ending that was a routine win.

Yes, White’s material advantage was less after 2 …  xf6 3 g4 hxg4 4 hxg4

xf6 3 g4 hxg4 4 hxg4  f7 5

f7 5  xf6

xf6  xf6 than it had been in the previous diagram.

xf6 than it had been in the previous diagram.

White to play

But it’s easier to win now. In fact, White has more than one way. He chose 6  d4

d4  e6 7

e6 7  c5 with the opposition.

c5 with the opposition.

Then came 7 …  e7 8

e7 8  d5

d5  d7 9

d7 9  e5

e5  e7 10 g5! resigns (10 …

e7 10 g5! resigns (10 …  f7 11

f7 11  d6

d6  g7 12

g7 12  e6

e6  g8 13

g8 13  f6

f6  h7 14

h7 14  f7).

f7).

Jose Capablanca formulated one of the most useful conversion plans: When pawns are equal and you are ahead the Exchange, look for a way to give back the Exchange to win a pawn. Your material edge will decline slightly. But the win is usually much easier to achieve.

We’ve seen how a king can demonstrate superiority over the rival king by limiting its scope, e.g. by seizing the opposition or throwing a shoulder block. Other pieces can dominate their rivals in a similar way.

Fischer – Addison

Cleveland 1957

White to play

White might win by creating a passed pawn, 1 b4  c7 2

c7 2  d3 and

d3 and  c4/b4-b5. But easier is 1

c4/b4-b5. But easier is 1  e5!.

e5!.

That virtually stalemates the knight, since 1 …  f6 2

f6 2  xf6! leads to a won pawn endgame (2 …

xf6! leads to a won pawn endgame (2 …  xf6 3

xf6 3  d3

d3  e5 4

e5 4  c4).

c4).

Black’s kingside majority can’t create a passed pawn after 4 … g4 5 b4 h5 6 a4 h4 7 h3!, which stops 7 … h3!.

Instead, Black tried to create a kingside mismatch with 1 …  h5 2

h5 2  d3 g4. White just ignored him: 3 b4 a6 4 a4 gxf3 5 gxf3

d3 g4. White just ignored him: 3 b4 a6 4 a4 gxf3 5 gxf3  h4 6 b5 axb5 7 a5! (breakthrough)

h4 6 b5 axb5 7 a5! (breakthrough)  h3 8 c6! resigns.

h3 8 c6! resigns.

When there are few pieces on the board, it stands to reason that dominating a single enemy piece can be decisive.

Keres – Hort

San Antonio 1972

White to play

It appears that White’s only winning idea is to create a passed e-pawn with a prepared f4-f5. (The immediate 1 f5? allows 1 … gxf5 2 gxf5  xe5!.)

xe5!.)

But 1 g5! was better. Black’s bishop joins his king in the penalty box.

Since there is no counterplay to worry about, White can explore various plans to win the f-pawn, such as bringing his king to e8 or his bishop to f6.

The game went 1 …  a4 2

a4 2  d4

d4  a6 3

a6 3  e4

e4  a4 4

a4 4  b8

b8  h8 5

h8 5  f8

f8  g7 6

g7 6  d8

d8  h7 7

h7 7  d3

d3  a3+ 8

a3+ 8  c4

c4  a4+ 9

a4+ 9  b5

b5  a3.

a3.

The maneuvering gave White a chance to look at tactics such as 10 e6  xd4 11 e7. But that fails after 11 …

xd4 11 e7. But that fails after 11 …  e3 12 e8(

e3 12 e8( )

)  xe8, a book draw, or 12 exf7

xe8, a book draw, or 12 exf7  g7.

g7.

So play continued 10  f8

f8  g7 11

g7 11  c8

c8  h7 12

h7 12  f8

f8  g7.

g7.

White to play

Black resigned after 13  xh8!

xh8!  xh8 14 e6+

xh8 14 e6+  g8 15 e7

g8 15 e7  a8 16

a8 16  f6! because the king and bishop get to dominate the rook.

f6! because the king and bishop get to dominate the rook.

The main line is 16 …  e8 17

e8 17  c6

c6  a8 – otherwise 18

a8 – otherwise 18  d7 wins.

d7 wins.

Then 18  c7 leaves Black with no good moves. After 18 …

c7 leaves Black with no good moves. After 18 …  h7 19

h7 19  d4!

d4!  g8 20

g8 20  d7 and 21 e8(

d7 and 21 e8( )+ because 20 …

)+ because 20 …  a7+ drops the rook.

a7+ drops the rook.

The most interesting battle that regularly occurs in an endgame is R-vs.-K. In some cases a king proves superior, such as when it can advance a passed pawn against a helpless rook.

But there are two cases when the rook wins the battle. The first occurs when a rook cuts a king off from the scene of action.

Balashov – Tiviakov

St. Petersburg 1993

Black to play

If it were White’s move he would draw with 1  d1 or 1

d1 or 1  d2.

d2.

But it’s Black’s turn and 1 …  d5! sealed off the White king from the kingside. That creates a K+P-vs.-R mismatch.

d5! sealed off the White king from the kingside. That creates a K+P-vs.-R mismatch.

Play went 2  a2

a2  g6 3

g6 3  f2 f5 and now 3

f2 f5 and now 3  d2

d2  xd2! 4

xd2! 4  xd2

xd2  g5! is distant and winning opposition (5

g5! is distant and winning opposition (5  e2

e2  g4! 6

g4! 6  f2

f2  f4).

f4).

On other moves, Black would make steady progress, e.g. 3  g2+

g2+  h5 4

h5 4  f2

f2  g4 5

g4 5  g2+

g2+  f3.

f3.

The best way to break a cutoff is to attack the rook, either with your king or your rook, offering a trade.

Zhelezny – Kim

Moscow 2008

Black to play

Here 1 …  d4 seems to win as in the previous diagram. For example, 2

d4 seems to win as in the previous diagram. For example, 2  c3

c3  d8 3

d8 3  c2 h4 4

c2 h4 4  c3

c3  f5 5

f5 5  c2 h3 6

c2 h3 6  c3

c3  f4 7

f4 7  c2 h2 8

c2 h2 8  h1

h1  g3.

g3.

Or 3  f1+

f1+  g5 4

g5 4  g1+

g1+  f4 7

f4 7  h1

h1  g4 8

g4 8  g1+

g1+  f3 9

f3 9  h1

h1  h8! and … h4-h3.

h8! and … h4-h3.

But White can draw with 2  d1! because his king is in the square (2 …

d1! because his king is in the square (2 …  xd1 3

xd1 3  xd1 h4 4

xd1 h4 4  e2 h3 5

e2 h3 5  f2 h2 6

f2 h2 6  g2).

g2).

Black tried 2 …  e4, hoping that a cutoff on the e-file would be sufficient. But White repeated the process, 3

e4, hoping that a cutoff on the e-file would be sufficient. But White repeated the process, 3  d2 h4 4

d2 h4 4  e1!. Black accepted a draw in view of 4 …

e1!. Black accepted a draw in view of 4 …  xe1 5

xe1 5  xe1 and

xe1 and  f2-g2 or 4 …

f2-g2 or 4 …  f4 5

f4 5  e2 h3 6

e2 h3 6  f1!. (Also 6

f1!. (Also 6  h1

h1  h4 7

h4 7  f2).

f2).

When the defending king is cut off by a rank, rather than a file, the situation is usually worse, as we’ll see.

The geography of the board provides us with the other way for a rook to win a battle against a king.

Taimanov – Larsen

Palma de Mallorca 1970

Black to play

Black’s king is not cut off. But the tempting 1 …  f4 2

f4 2  a4+

a4+  e5 allows to 3 g5!.

e5 allows to 3 g5!.

Then Black’s only active play, 3 …  g8+ 4

g8+ 4  h6

h6  h8+, is foiled by 5

h8+, is foiled by 5  g7!. That wins time for 6 g6. The winning Lucena position is near. (See Exact Ending 5 of Chapter Four.)

g7!. That wins time for 6 g6. The winning Lucena position is near. (See Exact Ending 5 of Chapter Four.)

Instead of this, Black chose the immediate 1 …  g8+! 2

g8+! 2  h5

h5  h8+!. This time the pawn is on the fourth rank and that means the king cannot approach the rook (3

h8+!. This time the pawn is on the fourth rank and that means the king cannot approach the rook (3  g6

g6  g8+ 4

g8+ 4  h7

h7  xg4! draw).

xg4! draw).

So play went 3  g5

g5  g8+! 4

g8+! 4  h4.

h4.

Black to play

Nothing has changed so 4 …  h8+! is best. Then on 5

h8+! is best. Then on 5  g3 Black would draw with 5 …

g3 Black would draw with 5 …  e5 6 g5?

e5 6 g5?  f5!.

f5!.

If White tries the cutoff, 6  f3, Black has the anti-cutoff method mentioned above, 6 …

f3, Black has the anti-cutoff method mentioned above, 6 …  e6 7 g5

e6 7 g5  e7 8

e7 8  g4

g4  f8! and draws.

f8! and draws.

Yet Black, a world-class player, didn’t check in the last diagram. He chose 4 …  e5?? and White cut the king off by a rank, 5

e5?? and White cut the king off by a rank, 5  a6!.

a6!.

This wins after 5 …  f4 6

f4 6  f6+

f6+  e5 7 g5! since Lucena is coming up. Or 5 …

e5 7 g5! since Lucena is coming up. Or 5 …  h8+ 6

h8+ 6  g5

g5  g8+ 7

g8+ 7  g6.

g6.

The advantage of knowing these techniques is that they spare you from a lot of calculating. For example, in the last diagram, 4 …  f4 does draw. But you have to see then 5

f4 does draw. But you have to see then 5  a4+ can be met by the surprising 5 …

a4+ can be met by the surprising 5 …  f3!. Knowing the checking distance is easier.

f3!. Knowing the checking distance is easier.

When a rook, not a king, is trying to promote a pawn, it usually belongs behind the pawn. Let’s see why.

White to play

White wins with 1 b7!. Since his rook is behind the pawn he can answer a Black rook move with 2 b8( ).

).

King moves will allow White’s king to penetrate, e.g. 1 …  e6 2

e6 2  f3

f3  d6 4

d6 4  g4 and

g4 and  g5xg6. The greater range of the ‘behind’ rook also wins after 2 …

g5xg6. The greater range of the ‘behind’ rook also wins after 2 …  f5 3

f5 3  b5+!.

b5+!.

But suppose we reverse the position of the rooks. Put the Black one at b1 and the White one at b8.

Then 1 b7? is an error because of 1 …  g7. White’s rook is frozen at b8 and his king can be checked away if it tries to reach the b-pawn.

g7. White’s rook is frozen at b8 and his king can be checked away if it tries to reach the b-pawn.

A better White try is to support the b-pawn with the king. But 1  f3

f3  g5 2

g5 2  e4

e4  g4 3

g4 3  d5

d5  xg3 4

xg3 4  c6 allows Black to draw with his pawn, 4 … g5.

c6 allows Black to draw with his pawn, 4 … g5.

When the player with advantage can steal the ‘behind’ role, the impact can be huge.

Georgiev – Kamsky

Istanbul 2012

White to play

White should draw because his rook is excellently placed. When he is forced give up his rook he can create one or two passed kingside pawns.

For example, 1 g5 fxg5+ 2  xg5 and then 2 …

xg5 and then 2 …  b2 3 f5 a1(

b2 3 f5 a1( ) 4

) 4  xa1

xa1  xa1 5 f6 draws.

xa1 5 f6 draws.

But White played 1  h5??, perhaps thinking he will have winning chances after 2

h5??, perhaps thinking he will have winning chances after 2  g6.

g6.

What he overlooked was 1 …  d4!. Black threatens to make his rook the one ‘behind,’ with 2 …

d4!. Black threatens to make his rook the one ‘behind,’ with 2 …  a4!. Then White can’t stop the a-pawn. Black ends up with an extra queen, not just a rook.

a4!. Then White can’t stop the a-pawn. Black ends up with an extra queen, not just a rook.

Seeing that, White played 2  xa2

xa2  xa2 3 f5. But Black’s king was fast, 3 …

xa2 3 f5. But Black’s king was fast, 3 …  b3 4 g5 fxg5 5

b3 4 g5 fxg5 5  xg5

xg5  c4 6 f6

c4 6 f6  d8 7

d8 7  g6

g6  d5, and White resigned.

d5, and White resigned.

If a rook reaches the seventh rank in a typical early endgame it exerts a powerful force because it attacks vulnerable pawns. This is true even when the defender’s king is not limited to the eighth rank.

Ivanchuk – Short

Amsterdam 1994

White to play

Everything seems defended until 1  d5!.

d5!.

If Black had tried 1 … c6 2  xe7

xe7  xe7 White would win with 3 g6 hxg6 4 hxg6 and

xe7 White would win with 3 g6 hxg6 4 hxg6 and  f7+.

f7+.

The pawn ending, 4 …  f8 5

f8 5  xf8

xf8  xf8, would also be lost, 6

xf8, would also be lost, 6  f3

f3  e7 7

e7 7  g4

g4  f6 7

f6 7  h5 (zugzwang)

h5 (zugzwang)  e7 8

e7 8  g5

g5  e6 9 c4!

e6 9 c4!  e7 10

e7 10  f5

f5  d6 11 b3!.

d6 11 b3!.

So, Black tried 1 …  xd5 2 exd5+

xd5 2 exd5+  xd5. But then 3

xd5. But then 3  f7:

f7:

Black to play

After 3 …  d6 4

d6 4  f3 Black runs out of useful moves, e.g. 4 … b6 5 axb6 cxb6 6

f3 Black runs out of useful moves, e.g. 4 … b6 5 axb6 cxb6 6  e4

e4  e6 7

e6 7  b7 b5 8

b7 b5 8  b6+! and wins.

b6+! and wins.

Instead, Black chose 3 … b6 4  xc7 bxa5 and was lost after 5

xc7 bxa5 and was lost after 5  f3

f3  f8+ 6

f8+ 6  e3 h6 7

e3 h6 7  xg7 (or 6 …

xg7 (or 6 …  g8 7

g8 7  a7).

a7).

Seizing the seventh is also an important defensive technique. In some cases it allows you to eliminate enough enemy pawns to draw.

Kasparov – Karpov

World Championship 1984

White to play

White cannot stop …  a8 and the advance of the a-pawn. He tried to raid the kingside with 1

a8 and the advance of the a-pawn. He tried to raid the kingside with 1  h5? h6 2

h5? h6 2  e5. But after 2 …

e5. But after 2 …  a8! he was too late, 3

a8! he was too late, 3  e6+

e6+  b5 4

b5 4  g6 a5 5

g6 a5 5  xg7 a4 6

xg7 a4 6  b7+

b7+  a5 and Black won.

a5 and Black won.

It was a good idea but a bad execution. The right way to raid was 1  e5!

e5!  a8 2

a8 2  e6+

e6+  c5 3

c5 3  e7 because White gets both kingside pawns.

e7 because White gets both kingside pawns.

Play would go 3 … a5 4  xg7 a4 5

xg7 a4 5  xh7 a3.

xh7 a3.

White to play

By exploiting the seventh rank, White has three passed pawns. His rook can get back just in time to give itself up for the a-pawn, 6  c7+!

c7+!  b4 7

b4 7  c1! a2 8

c1! a2 8  a1. Then his kingside pawns enable him to draw.

a1. Then his kingside pawns enable him to draw.

If a player has no pawns he usually needs the equivalent of an extra rook to win. That’s a lot. Therefore a wise defender wants to eliminate as many enemy pawns as possible.

And when there are pawns on both wings, the defender wants to get rid of the queenside pawns first. Why? Because his king is typically on the kingside and that makes it harder to stop a queenside passer.

Eliskases – Fischer

Buenos Aires 1960

Black to play

Black may have had hallucinations of winning when he played 1 …  c5?. If he can follow up with 2 … b5!, the bishop dominates the stalemated knight, which could be lost after …

c5?. If he can follow up with 2 … b5!, the bishop dominates the stalemated knight, which could be lost after …  g8-f8-e8-d8.

g8-f8-e8-d8.

But White saw 2 a4! and he gradually won after 2 …  g6 3

g6 3  g2

g2  f6 4

f6 4  f3

f3  e6 5

e6 5  e4

e4  f2 6 f5+

f2 6 f5+  d7 7

d7 7  a7 and

a7 and  d5.

d5.

Black should have drawn by swapping pawns – but not with 1 …  xf4 2

xf4 2  xb6, when White gets two queenside passers.

xb6, when White gets two queenside passers.

Correct is 1 …  xa3!. Then 2 bxa3?? c3! and the c-pawn queens. White has to play 2

xa3!. Then 2 bxa3?? c3! and the c-pawn queens. White has to play 2  xb6 but after 2 …

xb6 but after 2 …  xb2 3

xb2 3  xc4

xc4  c1 4 f5 h5 his chances are minimal.

c1 4 f5 h5 his chances are minimal.

When there are pawns on both wings, the player who is trying to win wants a majority – as large as possible – on the distant wing. If pawns are equal on that wing it’s usually very hard to win.

Anand – Genius

London 1994

White to play

But a win is possible if there is a one-pawn edge on the distant wing. And a two-pawn edge is better. That explains 1  d4!

d4!  xd4 2 exd4.

xd4 2 exd4.

White had the edge after 2 … f5 3 b4!  f6 4 c5! a6 5 a4

f6 4 c5! a6 5 a4  e7 6 b5! axb5 7 axb5 g5 8

e7 6 b5! axb5 7 axb5 g5 8  f2.

f2.

But he is not yet winning: If he advances his king to, say, a5, Black can create a counter-passer on the kingside.

However, Black rushed with the immediate 8 … h5?.

White to play

White switched gears with 9 h4!!. That ensures him of a kingside entry. He won after 9 … gxh4 10  f3

f3  e8 11

e8 11  f4

f4  d7 12

d7 12  g5

g5  d8 13

d8 13  xh4

xh4  d7 14

d7 14  xh5. On 10 …

xh5. On 10 …  f6 White can win with 11

f6 White can win with 11  f4

f4  g6 12 c6!, exploiting his big queenside majority.

g6 12 c6!, exploiting his big queenside majority.

The bigger-majority principle is particularly important in rook endgames. Suppose you are a pawn ahead. There are two scenarios:

In one of them, you have a 2-to-1 majority on the queenside and the pawns are balanced, three to three, on the kingside. Some positions like that are winnable. Many are not.

But suppose that you have a 3-to-1 edge on the queenside, while you opponent has a one-pawn majority on the kingside. Your chances of winning escalate sharply.

When all else fails, you can draw some hopeless-looking positions by arranging your pieces and pawns on impregnable squares.

Timman – Yusupov

Montpellier 1985

White to play

Usually a player needs a rook, bishop and pawn to balance a queen. Therefore White has a slight material edge. He might win if he captures Black’s a-pawn and pushes his own a-pawn.

And there’s also zugzwang. White found 1  f6! which seems to run Black out of useful moves:

f6! which seems to run Black out of useful moves:

He can’t safely move his king (1 …  g8 2

g8 2  xh6) or move his rook from the g-file (1 …

xh6) or move his rook from the g-file (1 …  c5 2

c5 2  f7+

f7+  h8 3

h8 3  g6!). If his rook leaves the rank White can create a passed pawn (1 …

g6!). If his rook leaves the rank White can create a passed pawn (1 …  g7 2 b4 axb4 3 a5

g7 2 b4 axb4 3 a5  xa5? 4

xa5? 4  f5+/5

f5+/5  xa5) or advance his king.

xa5) or advance his king.

Yet Black saved the game with 1 …  c5! and …

c5! and …  b4. There followed 2

b4. There followed 2  f7+

f7+  h8 3

h8 3  e8+

e8+  g7 4

g7 4  d7+

d7+  f6 5

f6 5  xc7

xc7  b4!.

b4!.

White to play

Now it’s White who has no particularly useful moves. His king cannot pass the fourth rank without losing the g-pawn. He can’t create a passed pawn. There are no zugzwangs. He tried 6  h7

h7  g6 7

g6 7  g3

g3  d6+ 8

d6+ 8  f3

f3  b4 9

b4 9  d7

d7  g5 but eventually agreed to a draw.

g5 but eventually agreed to a draw.

In some cases, a fortress is nothing more than a position that denies your opponent an entry point for his king.

Kramnik – Grischuk

Kazan 2011

Black to play

Black’s rook and knight are both en prise. Is he lost?

No, because of 1 …  b4!. Then 2

b4!. Then 2  xd6? allows 2 … b6+. So 2

xd6? allows 2 … b6+. So 2  xb4 axb4 is forced and 3

xb4 axb4 is forced and 3  xb4 was followed by 3 … b6!.

xb4 was followed by 3 … b6!.

The fortress is secure. Black can pass with …  d8-e7. If White’s king runs to the kingside, Black slams the door with …

d8-e7. If White’s king runs to the kingside, Black slams the door with …  g7. Draw.

g7. Draw.

When defending your pawns, the best place for your pieces is usually next to or behind the pawns. But when your opponent’s king got there first, the best defense may be attacking his pawns from behind.

Gipslis – Tal

Latvian Championship 1958

Black to play

Black’s position appears hopeless because of  xb7. On 1 …

xb7. On 1 …  g2 White can win with 2 c5 and

g2 White can win with 2 c5 and  c8-d6xb7. (Or, after 2 …

c8-d6xb7. (Or, after 2 …  d4, with 3 b5! as he did in the game, as we’ll see.)

d4, with 3 b5! as he did in the game, as we’ll see.)

A second idea is to trade a pair of pawns, 1 …  xc4 2

xc4 2  xb7, and defend with the king. But after 2 …

xb7, and defend with the king. But after 2 …  d6 3

d6 3  c8+!

c8+!  e5 (not 3 …

e5 (not 3 …  d7 4

d7 4  b6+!) 4

b6+!) 4  b6 Black is lost.

b6 Black is lost.

For example, 4 …  d4 5

d4 5  d6

d6  f1 6 b5 axb5 7 a6. Or 4 …

f1 6 b5 axb5 7 a6. Or 4 …  e6 5

e6 5  a7

a7  d7 8

d7 8  c6

c6  c8 9

c8 9  a7 and

a7 and  b8xa6. So, Black tried to attack the pawns with his king, 1 …

b8xa6. So, Black tried to attack the pawns with his king, 1 …  d4?. But after 2 c5

d4?. But after 2 c5  g2 3 b5! he resigned in view of the breakthrough, 3 … axb5 4 c6! bxc6 5 a6 c5 6

g2 3 b5! he resigned in view of the breakthrough, 3 … axb5 4 c6! bxc6 5 a6 c5 6  c6+ and the a-pawn queens.

c6+ and the a-pawn queens.

Right was 1 …  xc4! 2

xc4! 2  xb7

xb7  d4!. Then on 3

d4!. Then on 3  b6

b6  c3 4

c3 4  c5:

c5:

Black to play

The draw is secured by 4 …  b3!. For instance, 5

b3!. For instance, 5  c6

c6  f1 6

f1 6  d4+

d4+  a4 7 b5

a4 7 b5  xb5! 8

xb5! 8  xb5

xb5  xa5!.

xa5!.

Attack from behind arises in many bishop endings, both with bishops of the same color or of opposite color. It is also common in R-vs.-Ps.

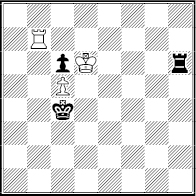

White to play

There’s no point in 1  a4+

a4+  f3. The rook must attack the pawns from a distance and prompt zugzwang. So let’s start with 1

f3. The rook must attack the pawns from a distance and prompt zugzwang. So let’s start with 1  a8.

a8.

Then on 1 …  f3 White attacks the d-pawn, 2

f3 White attacks the d-pawn, 2  d8!, He wins after 2 … d2+ 3

d8!, He wins after 2 … d2+ 3  d1 e2+ 4

d1 e2+ 4  xd2

xd2  f2 5

f2 5  f8+. The same for 3 …

f8+. The same for 3 …  f2 4

f2 4  f8+/5

f8+/5  e2.

e2.

The best try is 2 …  e4. But White passes, 3

e4. But White passes, 3  d7!, to create zugzwang, e.g. 3 … e2 4

d7!, to create zugzwang, e.g. 3 … e2 4  d2! or 3 … d2+ 4

d2! or 3 … d2+ 4  e2

e2  f4 5

f4 5  d4+

d4+  e5 6

e5 6  xe3.

xe3.

Back at the diagram Black has a trickier defense in 1 …  d4!. Again White should attack from behind, 2

d4!. Again White should attack from behind, 2  e8!. But this time Black can set a trap, 2 …

e8!. But this time Black can set a trap, 2 …  c3 3

c3 3  xe3??

xe3??  c2!, threatening 4 … d2+.

c2!, threatening 4 … d2+.

White has to play the accurate 3  d1! and 3 …

d1! and 3 …  d4 4

d4 4  e7! to create zugzwang, e.g. 4 … e2+ 5

e7! to create zugzwang, e.g. 4 … e2+ 5  d2

d2  c4 6

c4 6  e4+

e4+  d5 7

d5 7  xd3.

xd3.

The more valuable the piece, the less likely it is to be sacrificed in an endgame. Queen sacrifices only occur in rare combinations or composed studies. But there are cases when a minor piece can be profitably given up to obtain one or more passed pawns.

Zso. Polgar – Kramnik

Guarapuava 1991

Black to play

White traded off a Black d-pawn with her last moves. She hopes to draw by eliminating the last pawns when Black advances to b3.

Black could try to win by maneuvering the knight to c4. But much easier is 1 …  xa2! and 2

xa2! and 2  xa2 a4.

xa2 a4.

A pawn must queen after 3  e4 b3 4

e4 b3 4  b1 a3 5

b1 a3 5  d3 a2.

d3 a2.

A piece sacrifice is most likely to succeed when it leaves your opponent with no piece stronger than a knight. Second best is leaving your opponent with a bishop, as we saw in the discussion of mismatch.

In bishop endgames, what matters most is the color of the squares that your pawns and your opponent’s pawns are on.

White to play

This textbook example illustrates how useless pawns can be on the wrong colored squares. With 1 c5! and 2  b3 White creates an ironclad blockade.

b3 White creates an ironclad blockade.

For example 1 …  xc5 2

xc5 2  b3 e5 3

b3 e5 3  e6

e6  c7 4

c7 4  e4. Black cannot make progress if White passes with bishop moves to g4, f5, e6, etc.

e4. Black cannot make progress if White passes with bishop moves to g4, f5, e6, etc.

There’s a general rule: In most cases you want your pawns on squares of the opposite color of your bishop. Even with three extra pawns in the last example Black couldn’t win because they were on the wrong color squares.

The pawns lose their offensive power when they share squares with your bishop, as they did in the last example.

The endgame technique that typically takes the longest to execute is creating and exploiting a second weakness in the enemy camp. It’s a concept that also occurs in middlegames. But it yields the clearest result in an endgame.

P. Nikolic – Movsesian

Polanica Zdroj 1996

Black to play

Black’s a-pawn is White’s only target. After 1 …  c7 Black was ready to free his rook for duty with 2 …

c7 Black was ready to free his rook for duty with 2 …  b6.

b6.

But White won by opening a new front, 2 h5!. Then 2 … g5 would lose to 3  e4 and 4

e4 and 4  f5.

f5.

Black had to play 2 … gxh5 3  xh5. Now on the passive 3 …

xh5. Now on the passive 3 …  h8 White gets the superior king position, 4

h8 White gets the superior king position, 4  e4

e4  d6 5

d6 5  f5

f5  e7 after which he can win by activating his rook with 6

e7 after which he can win by activating his rook with 6  h1 and 7

h1 and 7  e1+/8

e1+/8  e6 or 7

e6 or 7  c1.

c1.

Black played 3 …  g8 instead. He was hoping that White would trade pawns (4

g8 instead. He was hoping that White would trade pawns (4  xh6?

xh6?  xg4) or be forced to use his rook to defend his g-pawn. Play went 4

xg4) or be forced to use his rook to defend his g-pawn. Play went 4  h4

h4  d7 5

d7 5  e4

e4  e6.

e6.

White to play

But White turned the guard duty over to his king, 6  f3!

f3!  h8 7

h8 7  h5

h5  h7 8

h7 8  g3. When Black tried to activate his rook, 8 …

g3. When Black tried to activate his rook, 8 …  d7, White made it passive again with 9

d7, White made it passive again with 9  a5!.

a5!.

It still might seem that Black was holding after 9 …  a7 10

a7 10  h4

h4  f7 11

f7 11  h5

h5  g7 12 f5

g7 12 f5  h7. White had no king entry on the kingside.

h7. White had no king entry on the kingside.

White to play

However, the passivity of Black’s rook proved to be fatal after 13  c5

c5  c7 14 a4!. The threat was 15 b5 and there was no relief in 14 …

c7 14 a4!. The threat was 15 b5 and there was no relief in 14 …  b7 15

b7 15  xc6

xc6  xb4 16

xb4 16  xf6.

xf6.

The rest was 14 …  g7 15 b5 axb5 16 axb5

g7 15 b5 axb5 16 axb5  b7 17 bxc6

b7 17 bxc6  c7 18

c7 18  c1

c1  c8 19 c7

c8 19 c7  f7 20

f7 20  c6

c6  g7 21

g7 21  h4

h4  f7 22

f7 22  g3 resigns, in view of the threat of

g3 resigns, in view of the threat of  f4-e4-d5-d6.

f4-e4-d5-d6.

The ultimate defensive trick is to draw by means of stalemate. This may sound like a rare and remote possibility. It isn’t.

Stalemate appears regularly in Exact Endings:

It’s how the defender can often draw in K+P-vs.-K. The same goes for K+Q-vs-K+P when the pawn is on a bishop or rook file. Stalemate is the key to the ‘wrong bishop’ case of K+B+RP-vs.-K and in many versions of K+Q-vs.-K+R. A lone king draws against a king and two knights because of stalemate.

And you’ll find it in many cases of K+R+P-vs.-K+R.

Black to play

Black’s king is cut off. White threatens  g4+ followed

g4+ followed  e8 or

e8 or  f7.

f7.

But Black has one way to draw, 1 …  a7+! 2

a7+! 2  f6

f6  f8!.

f8!.

The outlook still looks grim after 3  b4!. White threatens 4

b4!. White threatens 4  b8 mate and he would meet 3 …

b8 mate and he would meet 3 …  a8 with 4

a8 with 4  h4!, reaching a winning Exact Ending (‘When Philidor Fails’ in Chapter Four).

h4!, reaching a winning Exact Ending (‘When Philidor Fails’ in Chapter Four).

But the position after 3  b4 is a draw thanks to 3 …

b4 is a draw thanks to 3 …  f7+! since 4 exf7 is stalemate. Similar tricks occur in K+R+B-vs.-K+R.

f7+! since 4 exf7 is stalemate. Similar tricks occur in K+R+B-vs.-K+R.

There is no secret to mastering stalemate. The main thing is simply to be aware of the possibility.

Kramnik – Leko

Tilburg 1997

Black to play

Black foresaw this position earlier and forced White to bring his king forward to g6. Black’s king appears vulnerable to a different kind of trick – 1 … d2 allows 2  d5! and 2 …

d5! and 2 …  xd5 3

xd5 3  b8+ and mates.

b8+ and mates.

Black has a tempting defense, 1 …  d6+. But stronger was 1 …

d6+. But stronger was 1 …  xb5!! and then 2

xb5!! and then 2  bxb5 d2. He threatened to queen the d-pawn.

bxb5 d2. He threatened to queen the d-pawn.

On 3  b1 he would avoid 3 … d1(

b1 he would avoid 3 … d1( ) 4

) 4  xd1

xd1  xd1?? 5

xd1?? 5  e8 mate – and draw instead with 4 …

e8 mate – and draw instead with 4 …  d6+! because 5

d6+! because 5  xd6 is stalemate. Or simply 3 …

xd6 is stalemate. Or simply 3 …  d6+! and 4 … d1(

d6+! and 4 … d1( ).

).

So the crucial position arose after White met 2 … d2 with 3  bd5.

bd5.

Black to play

Black drew with the dramatic 3 … d1( ) 4

) 4  xd1

xd1  d6+! 5

d6+! 5  xd6, stalemate. And with that we leave the learning of endgame techniques and see how many trade secrets you remember – and can use.

xd6, stalemate. And with that we leave the learning of endgame techniques and see how many trade secrets you remember – and can use.

Set up each of these positions on a computer screen or board. Then:

(a) Try to figure out which technique – or techniques – can be used. Both players may have techniques available to them. Or one player might use more than one technique.

(b) Try to find the best play, without moving the pieces.

(c) Then try to find the best play, with moving the pieces.

11 Kavalek – Bilek

Sousse 1967

White to play

How can White take advantage of Black’s piece placement?

12 Fischer – Reshevsky

Los Angeles 1961

White to play

With no passed or queenside pawns White’s chances seem slim. He drew after 1  e4?. Did he have better?

e4?. Did he have better?

13 Bareev – Azmaiparashvilli

Shenyang 2000

Black to play

Black has more than one way to win. Which is the easiest?

14 Timman – Spassky

Hilversum 1983

Black to play

White threatens to win the knight with 1  e7+

e7+  c8 2

c8 2  e8+ or 1 f7. What can Black do?

e8+ or 1 f7. What can Black do?

15 Grischuk – J. Polgar

Biel 2007

Black to play

A knight and two connected pawns usually beats a knight. Why is this position different?

16 Hort – Doncevic

Bundesliga 1983

White to play

Black wants to create a counter-passer with … e5+. What can White do?

17 Ljubojevic – Smeets

Amsterdam 2007

White to play

White is in check and will lose the c5-pawn. What’s the difference between 1  e5 and 1

e5 and 1  c7 ?

c7 ?

18 Carlsen – Morozevich

Morelia-Linares 2007

Black to play

Black can win the kingside pawns beginning with 1 …  xf4. Should he?

xf4. Should he?

19 Mieses – Gunsberg

Hanover 1902

White to play

White has an extra pawn but no passer. What should he do?