xc3 Exchange sacrifice in the Sicilian Defense the same way that he knows when to answer … g6 with h2-h4-h5. He recognizes the pattern. That tells him what is likely to be worth calculating.

xc3 Exchange sacrifice in the Sicilian Defense the same way that he knows when to answer … g6 with h2-h4-h5. He recognizes the pattern. That tells him what is likely to be worth calculating.A master can calculate sacrifices better than you. But before he starts counting out five-move variations, he has to come up with one move – the one that starts the sacrifice. He doesn’t do this by looking at every possible offer of material. He relies on his know-how – the sacrifices that occurred in similar positions in previous games. There are very few new, unique sacks.

Standard sacrifices are a form of priyome. A master knows, for instance, the …  xc3 Exchange sacrifice in the Sicilian Defense the same way that he knows when to answer … g6 with h2-h4-h5. He recognizes the pattern. That tells him what is likely to be worth calculating.

xc3 Exchange sacrifice in the Sicilian Defense the same way that he knows when to answer … g6 with h2-h4-h5. He recognizes the pattern. That tells him what is likely to be worth calculating.

In this chapter we’ll examine 25 of the most commonly occurring sacrifices. These are not sham sacrifices, as Rudolf Spielmann called them. Those are really combinations, such as the ancient  xh7+/ …

xh7+/ …  xh7/

xh7/  g5+ against a castled king. Sham sacks lead to a quick and definite outcome.

g5+ against a castled king. Sham sacks lead to a quick and definite outcome.

A real sacrifice, on the other hand, may just offer compensation and alter the dynamic of the middlegame. They are harder to learn – and that’s why they are the trade secrets of masters.

When White plays d4-d5 as a sacrifice he wants to open the d- or e-file for his heavy pieces and perhaps plant a knight on d4. This happens after openings as varied as the Caro-Kann and Nimzo-Indian Defenses, and the Queen’s Gambit, both Accepted and Declined.

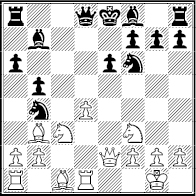

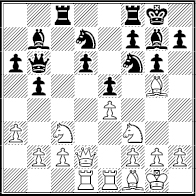

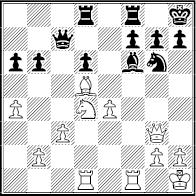

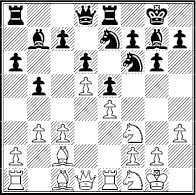

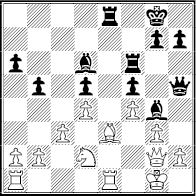

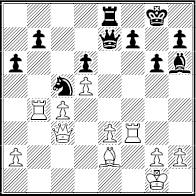

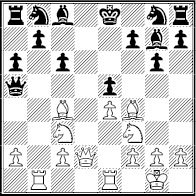

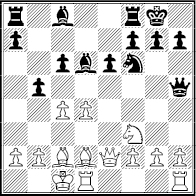

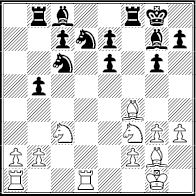

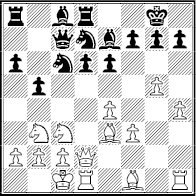

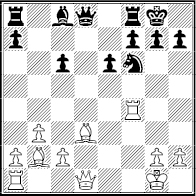

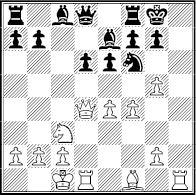

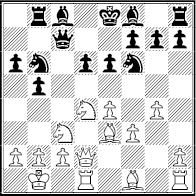

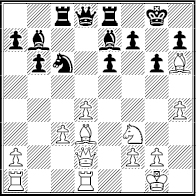

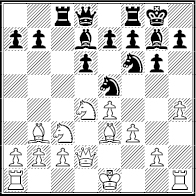

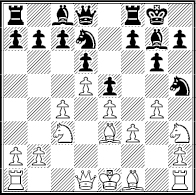

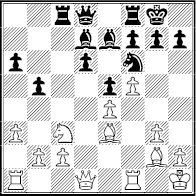

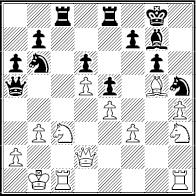

Spassky – Avtonomov

Leningrad 1949

White to play

In this position, from a QGA, Black controls d5 five times compared with two times for White. Yet 1 d5! works. On 1 …  fxd5? Black is lost because of 2 a3! (2 …

fxd5? Black is lost because of 2 a3! (2 …  c6 3

c6 3  xd5 or 2 …

xd5 or 2 …  xc3 3

xc3 3  xd8 with check).

xd8 with check).

Moreover, both 1 …  xd5 and 1 …

xd5 and 1 …  bxd5 allow a strong 2

bxd5 allow a strong 2  g5!. After Black chose 1 …

g5!. After Black chose 1 …  bxd5 2

bxd5 2  g5!, White had two pins and a winning threat of 3

g5!, White had two pins and a winning threat of 3  xd5

xd5  xd5 4

xd5 4  xd5

xd5

Black defended with 2 …  e7 3

e7 3  xf6 gxf6. Then on 4

xf6 gxf6. Then on 4  xd5 he could recapture with the pawn and keep his bishop so that

xd5 he could recapture with the pawn and keep his bishop so that  d4-c6 is ruled out.

d4-c6 is ruled out.

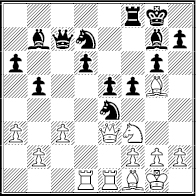

White would then retain a strong initiative after 4 … exd5 5  d4!

d4!  d7 (else

d7 (else  f5) 6

f5) 6  e1

e1  f8 7

f8 7  h5.

h5.

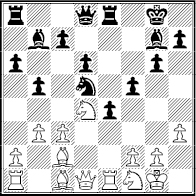

Instead, the game went 4  xd5

xd5  xd5 5

xd5 5  xd5 exd5. White does not have a forced win, just a terrific position after 6

xd5 exd5. White does not have a forced win, just a terrific position after 6  d4!.

d4!.

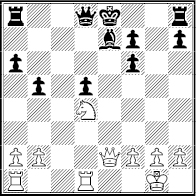

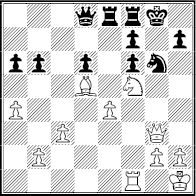

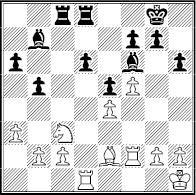

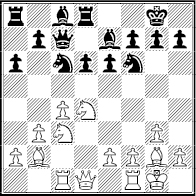

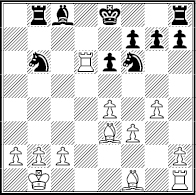

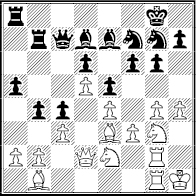

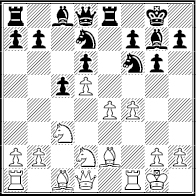

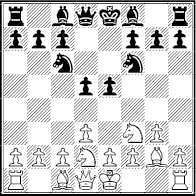

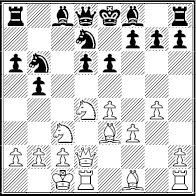

Black to play

White threatens to exploit the e-file pin with heavy pieces and  f5 or

f5 or  c6. Black tried 6 …

c6. Black tried 6 …  f8 7

f8 7  f5 h5?, overlooking 8

f5 h5?, overlooking 8  xd5!

xd5!  xd5 9

xd5 9  xe7+

xe7+  g8 10

g8 10  xf6. He resigned in view of 11

xf6. He resigned in view of 11  g7 mate or 12

g7 mate or 12  e7+.

e7+.

Better was 6 …  d7 7

d7 7  e1

e1  a7. But White would have a strong initiative, well worth a pawn, after 8

a7. But White would have a strong initiative, well worth a pawn, after 8  ac1

ac1  f8 9

f8 9  h5.

h5.

The moral: Even when d4-d5 looks impossible, it’s worth a second look.

Another form of d4-d5 occurs when White has a pawn at e4 and will meet … exd5 with e4-e5.

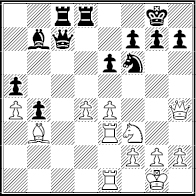

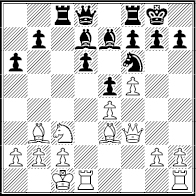

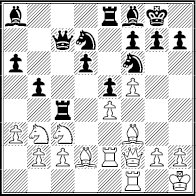

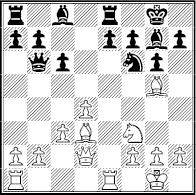

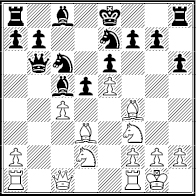

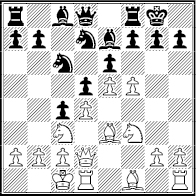

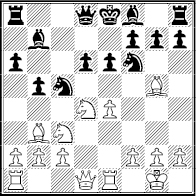

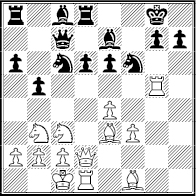

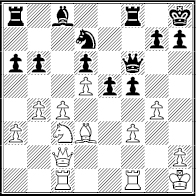

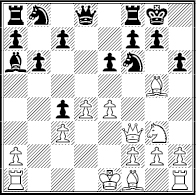

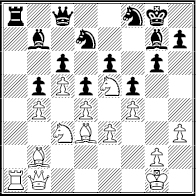

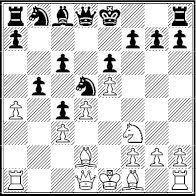

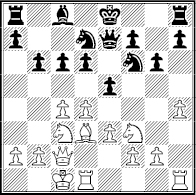

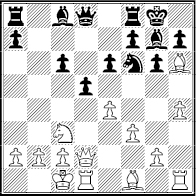

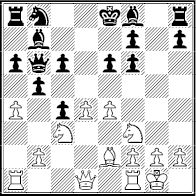

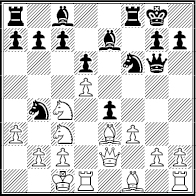

Keres – Fine

Ostende 1937

White to play

The tempting 1 e5? surrenders a wonderful outpost to Black at d5 and opens the diagonal of his bishop at b7. The position calls for 1 d5! instead.

Many of the most common real sacrifices are not forcing. Here, for example, Black can refuse the pawn with 1 … e5.

But the new pawn structure favors White after 2  g5

g5  d7 3

d7 3  h4 and 4

h4 and 4  f5. Or after 2

f5. Or after 2  g5, with threats of 3 d6 and 3

g5, with threats of 3 d6 and 3  xh7

xh7  xh7 4

xh7 4  h3.

h3.

So, Black played 1 … exd5. White would get little from 2 exd5?  xd5. But 2 e5! drove away the Black knight and made e5-e6!? possible.

xd5. But 2 e5! drove away the Black knight and made e5-e6!? possible.

For example, 2 …  e4 can be met by 3 e6! fxe6 4

e4 can be met by 3 e6! fxe6 4  xe4 dxe4 5

xe4 dxe4 5  g5. White would have a dangerous attack with 6

g5. White would have a dangerous attack with 6  xh7+, 6

xh7+, 6  xe6+ or 6

xe6+ or 6  xe6.

xe6.

Instead, the game went 2 …  d7 3

d7 3  g5.

g5.

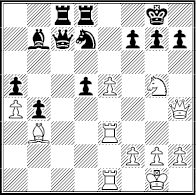

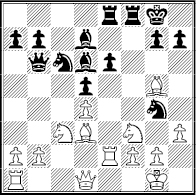

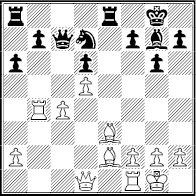

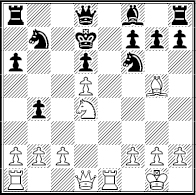

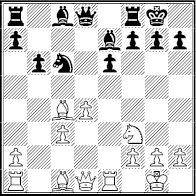

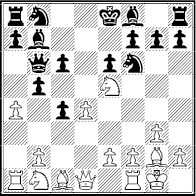

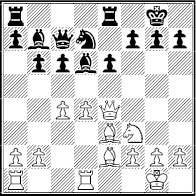

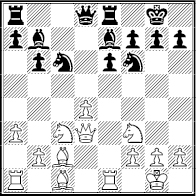

Black to play

Now on 3 … h6 White can draw with perpetual check after 4 e6 hxg5 5 exf7+  xf7 6

xf7 6  e7+

e7+  g6! 7

g6! 7  xg7+ or look for more.

xg7+ or look for more.

Black played 3 …  f8?, a natural but faulty follow-up to his previous move. He lost after 4

f8?, a natural but faulty follow-up to his previous move. He lost after 4  xh7!

xh7!  xh7 5

xh7 5  h3 and 5 …

h3 and 5 …  c1 6

c1 6  xh7+

xh7+  f8 7

f8 7  he3.

he3.

xc3

xc3This arises almost exclusively in the Sicilian Defense. But it is so common and so crucial to the outcome of middlegames that it is one of the most important recurring sacrifices.

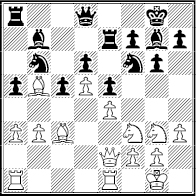

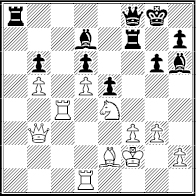

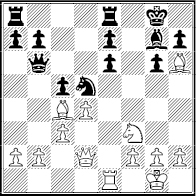

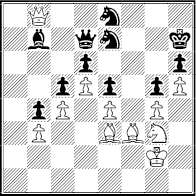

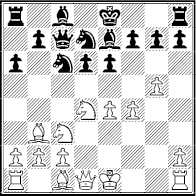

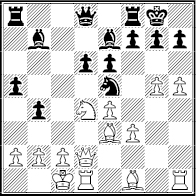

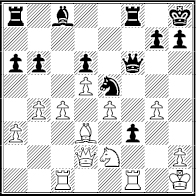

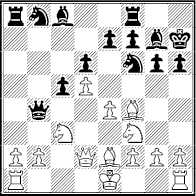

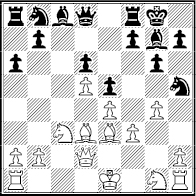

Thorhallsson – Hillarp Persson

Icelandic Team Championship 2003

Black to play

Black appears to be worse because his backward d-pawn is a chronic weakness. But he seized the initiative with 1 …  xc3! 2

xc3! 2  xc3

xc3  xe4.

xe4.

After White met the threats (…  xc3/ …

xc3/ …  xf2+/ …

xf2+/ …  xf2) with 3

xf2) with 3  e3 the forced moves were over and we can evaluate the sacrifice:

e3 the forced moves were over and we can evaluate the sacrifice:

Black has improved the scope of his bishop at b7 and threatens to push his center pawns down White’s throat. His chances are better in a middlegame than in an ending so he played 3 …  c7! and 4 c3 f5.

c7! and 4 c3 f5.

White to play

Theoretically White is about a half a pawn ahead. But the initiative and center control matter more. White played 5  c1 and chances would be roughly equal after 5 … f4. But it was much harder to play the White pieces and Black won.

c1 and chances would be roughly equal after 5 … f4. But it was much harder to play the White pieces and Black won.

When Black does not immediately win the e4-pawn, White’s king safety and the weakness of his pawns are keys to Black’s compensation.

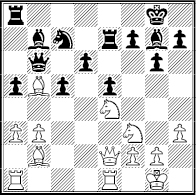

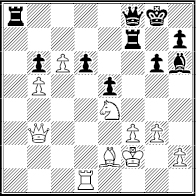

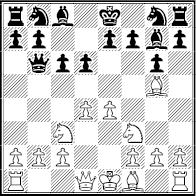

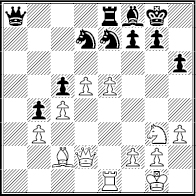

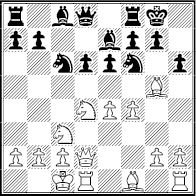

J. Polgar – I. Ivanov

New York 1989

Black to play

A priyome in this position is g2-g4-g5 by White and … b5-b4 by Black, as we saw in Chapter One. Since it’s Black move, he can start the chain reaction and would likely stand well after 1 … b5 2 g4 b4 and either 3 g5 bxc3 4 gxf6 cxb2+ and 5 …  xf6 or 3

xf6 or 3  d5

d5  xd5 4

xd5 4  xd5

xd5  c7.

c7.

But more promising is 1 …  xc3! 2 bxc3

xc3! 2 bxc3  c6. Black threatens to take on e4 as well as build up on the queenside with …

c6. Black threatens to take on e4 as well as build up on the queenside with …  a5/ …

a5/ …  c8.

c8.

He would stand better after 3  d5

d5  xd5 4 exd5

xd5 4 exd5  a5 5

a5 5  b2

b2  c8, with threats to c3 and prospects of … e4 or …

c8, with threats to c3 and prospects of … e4 or …  c4-a4.

c4-a4.

Instead, play went 3  b2

b2  xe4. Black’s compensation was more than enough because of White’s unsafe king. White bet on a kingside attack and was lost after 4

xe4. Black’s compensation was more than enough because of White’s unsafe king. White bet on a kingside attack and was lost after 4  g4 d5 5

g4 d5 5  d3

d3  a5 6

a5 6  h6

h6  f6 and now 7

f6 and now 7  g3?!

g3?!  xg3 8

xg3 8  xg7

xg7  xg7 9 f6

xg7 9 f6  h5! won.

h5! won.

A kind of reversed image of …  xc3 is an Exchange sacrifice on f6 or f3. Its main aim is to damage the enemy’s castled position. If the sacker can also pick off a pawn, all the better. This is a common theme in the French Defense:

xc3 is an Exchange sacrifice on f6 or f3. Its main aim is to damage the enemy’s castled position. If the sacker can also pick off a pawn, all the better. This is a common theme in the French Defense:

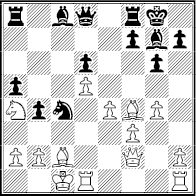

Rovner – Tal

Riga 1955

Black to play

If White had seen it coming he would have tried something like 1  d2. But he chose 1 h3? and allowed 1 …

d2. But he chose 1 h3? and allowed 1 …  xf3!.

xf3!.

Declining the sack, 2 hxg4, fails to 2 …  xd4! 3 gxf3

xd4! 3 gxf3  xf3+ 4

xf3+ 4  g2

g2  xg5. Black would have two pawns for the Exchange – more than enough ‘comp.’

xg5. Black would have two pawns for the Exchange – more than enough ‘comp.’

White preferred 2 gxf3  h2! 3

h2! 3  g2. But he was worse after 3 …

g2. But he was worse after 3 …  xd4 4

xd4 4  e3 h6! and 5

e3 h6! and 5  h4

h4  f4.

f4.

For example, 6  b1

b1  f8!, piling up against f3, is better than the complications of 6 …

f8!, piling up against f3, is better than the complications of 6 …  xe3 7 fxe3

xe3 7 fxe3  hxf3 8

hxf3 8  f2!.

f2!.

Instead, the game went 6  g6?!

g6?!  xe3 7

xe3 7  xe8 and Black won after 7 …

xe8 and Black won after 7 …  hxf3! 8

hxf3! 8  xd7

xd7  xh4+.

xh4+.

The White version of this,  xf6, is a familiar guest in the Sicilian Defense. The positional benefits often include securing outposts at d5 or f5.

xf6, is a familiar guest in the Sicilian Defense. The positional benefits often include securing outposts at d5 or f5.

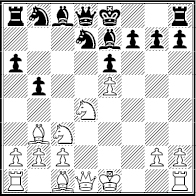

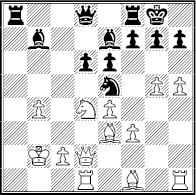

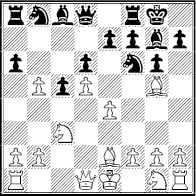

Stein – Parma

Lvov 1962

White to play

The natural 1  f5 is handled by 1 …

f5 is handled by 1 …  e7. White secured the f5 square and the win of a pawn for the Exchange with 1

e7. White secured the f5 square and the win of a pawn for the Exchange with 1  xf6! gxf6 2

xf6! gxf6 2  f2.

f2.

A key point is that 2 …  g7 3

g7 3  f1

f1  e7?? allows 4

e7?? allows 4  f5+. Black tried 2 …

f5+. Black tried 2 …  g8, leaving White with a choice of 3

g8, leaving White with a choice of 3  xf6

xf6  e7 or the more ambitious ideas, 3

e7 or the more ambitious ideas, 3  e3 and

e3 and  h6/

h6/ f5 or building up with 3

f5 or building up with 3  f1.

f1.

He chose the latter and play went 3  f1

f1  de8 4

de8 4  f5

f5  d8 5

d8 5  g3.

g3.

Black to play

White’s main threat is h2-h4-h5, which, thanks to the knight on f5, would be decisive. (In fact, 5 h4 is stronger than 5  g3.)

g3.)

Black began to give back material, 5 …  h8 6

h8 6  xd6 (6 h4!)

xd6 (6 h4!)  e7 7

e7 7  xf6. Then he gambled on 7 …

xf6. Then he gambled on 7 …  xe4? based on 8

xe4? based on 8  xe4

xe4  xf6 and 8

xf6 and 8  xe4

xe4  xd5.

xd5.

But this lost to 8  xf7+!

xf7+!  xf7 9

xf7 9  xf7

xf7  e5 10 c4. The outcome would have been unclear after 7 …

e5 10 c4. The outcome would have been unclear after 7 …  d7 8 e5

d7 8 e5  e7.

e7.

Pawn chains encourage attacks on the flanks of the chain. With White pawns at d4 and e5 facing Black pawns at d5 and e6, a standard idea is f4-f5/ … exf5 – and even the follow-up of e5-e6 – to open the center.

But another recurring theme is blasting open the center by giving up a knight for two chain pawns.

Jansa – Gligoric

Nice 1974

Black to play

That happens most often when White creates a chain with links at e4 and d5, as in the King’s Indian and Benoni Defenses but also in 1 e4 e5 openings. This position arose from a Ruy Lopez.

White prepares to pressure the queenside with a3-a4 and  d2. Or with

d2. Or with  d2-c4 and …

d2-c4 and …  xc4/bxc4 and

xc4/bxc4 and  fb1.

fb1.

Black acted first, 1 …  bxd5! 2 exd5

bxd5! 2 exd5  xd5. At meager cost his center pawns – and the bishops behind them – became an offensive force following 3

xd5. At meager cost his center pawns – and the bishops behind them – became an offensive force following 3  b2

b2  b6 4

b6 4  e4

e4  c7!.

c7!.

Black threatened …  xb5 but also prepared … d5 followed by … e4.

xb5 but also prepared … d5 followed by … e4.

White to play

He was better after 5  a4 d5 6

a4 d5 6  ed2 e4! 7

ed2 e4! 7  xg7

xg7  xg7 and then 8

xg7 and then 8  h2

h2  e6 9

e6 9  ac1 f5.

ac1 f5.

Black’s edge became obvious after 10 f3 c4+! (11  h1

h1  c5 or 11

c5 or 11  f2

f2  xf2+ 12

xf2+ 12  xf2

xf2  c5 and …

c5 and …  d3+). But even without 10 f3 he would have a strong game with …

d3+). But even without 10 f3 he would have a strong game with …  f4-d3 or …

f4-d3 or …  f8 and … f4.

f8 and … f4.

A variation on this theme is a sacrifice on e4 rather than d5. If Black then wins the d5-pawn the effect is the same.

Geller – Eingorn

Riga 1985

Black to play

Having seen the last example, you might start by looking at 1 …  exd5. But 1 …

exd5. But 1 …  xe4! and 2

xe4! and 2  xe4 f5 is more forcing.

xe4 f5 is more forcing.

Black gets to mobilize his center pawns immediately thanks to his threats to take on c3. Play went 3  c2 e4 4

c2 e4 4  d4

d4  xd5.

xd5.

The game could become wildly unbalanced after 5  d2 c5 6

d2 c5 6  e2 b4 7 c4!?

e2 b4 7 c4!?  xa1 8

xa1 8  xa1 or 5 … b4 6 c4!

xa1 or 5 … b4 6 c4!  xd4 7 cxd5

xd4 7 cxd5  xa1 8

xa1 8  xa1

xa1  xd5 9

xd5 9  xb4.

xb4.

White to play

Instead, White replied 5  e2? and then 5 …

e2? and then 5 …  xc3 6

xc3 6  xc3

xc3  xc3 7

xc3 7  b1.

b1.

Black didn’t want to give his opponent attacking chances along the a1-h8 diagonal after 7 …  xe1 8

xe1 8  xe1 followed by

xe1 followed by  b2.

b2.

He felt he could win with his center pawns alone and did so after 7 … c5! 8  b2

b2  xb2! 9

xb2! 9  xb2 d5 10

xb2 d5 10  c1 d4 11

c1 d4 11  d1

d1  d6.

d6.

This arises in several different pawn structures with an open file. The sacrificer, White or Black, wants to close the file and secure positional benefits like a protected passed pawn.

Epishin – Dolmatov

Russian Team Championship 1992

White to play

White can occupy c7 with his rook but it can be challenged by …  c8.

c8.

Better is 1  c6!, threatening the pawns on b6 and d6. After the forced 1 …

c6!, threatening the pawns on b6 and d6. After the forced 1 …  xc6 2 dxc6 we can evaluate:

xc6 2 dxc6 we can evaluate:

(a) White created a protected passed pawn at c6.

(b) He opened a splendid diagonal leading to f7 and threatens  c4.

c4.

(c) He is virtually certain to win back at least one pawn.

Of course, Black has an extra Exchange. But rooks need files to prove they are superior to minor pieces. Since the c-file is now plugged up, a diagonal, a2-g8, counts much more.

Black to play

This became evident as the game went 2 …  h8 3

h8 3  xd6 and now 3 …

xd6 and now 3 …  c1!? 4

c1!? 4  c3

c3  a3 5

a3 5  e6

e6  g7 6

g7 6  g2.

g2.

White could have won a second pawn (6  xe5 or 6

xe5 or 6  xe5). Or he could have pushed the c-pawn. But he preferred to exploit the a2-g8 diagonal, with 6 …

xe5). Or he could have pushed the c-pawn. But he preferred to exploit the a2-g8 diagonal, with 6 …  e7 7

e7 7  c4

c4  aa7 8 h4

aa7 8 h4  xe6 9

xe6 9  xe6

xe6  f8 10

f8 10  b3!.

b3!.

He was preparing  c4 and

c4 and  g5-f7+. The game ended with 10 … h6 11

g5-f7+. The game ended with 10 … h6 11  c4! g5 12 hxg5 hxg5 13

c4! g5 12 hxg5 hxg5 13  e6 g4 14 fxg4. Black resigned in view of

e6 g4 14 fxg4. Black resigned in view of  f6 followed by

f6 followed by  e8! or

e8! or  h5!.

h5!.

The file plugger works best when it not only limits enemy rooks but benefits one of your minor pieces, such as White’s light-squared bishop in the last example, and Black’s in the next.

Matanovic – Szabo

Saltsjobaden 1952

Black to play

White threatens to win a second pawn,  xd5+. If Black defends with …

xd5+. If Black defends with …  f7, White can continue with

f7, White can continue with  f3-e5 or perhaps a2-a4 and enjoy an edge.

f3-e5 or perhaps a2-a4 and enjoy an edge.

So Black played 1 …  e4! and 2

e4! and 2  xe4 fxe4. Then White had no targets to attack. His rooks don’t play because the e-file is plugged. Black’s bishop goes from bad to good, e.g. 3 …

xe4 fxe4. Then White had no targets to attack. His rooks don’t play because the e-file is plugged. Black’s bishop goes from bad to good, e.g. 3 …  f3! 4

f3! 4  f2 g5 or 4

f2 g5 or 4  f1

f1  h6.

h6.

But one of the advantages of having an extra Exchange is that you can give it back. White chose 3  f1. He invited 3 …

f1. He invited 3 …  h3 4

h3 4  f2

f2  xf1 5

xf1 5  xf1 when he would still be a pawn up and ready for 6 a4.

xf1 when he would still be a pawn up and ready for 6 a4.

Black to play

Black appreciated that and preferred 3 …  f3 so that he could answer 4

f3 so that he could answer 4  f2 with 4 …

f2 with 4 …  g4, threatening …

g4, threatening …  xf4 or … h5-h4.

xf4 or … h5-h4.

White kept winning chances with 4  xf3! and 4 … exf3 5

xf3! and 4 … exf3 5  f2

f2  e6 6

e6 6  e1! (not 6

e1! (not 6  f1

f1  xf4 7

xf4 7  xf4

xf4  e2 or 7 gxf4

e2 or 7 gxf4  g4+ and 8 …

g4+ and 8 …  g2+).

g2+).

The upshot is that he can trade rooks and try to win the f3-pawn in the endgame. Black had enough counterplay, 6 … h6 7  d2

d2  f7 8

f7 8  xe6

xe6  xe6 9 h3 g5!, to draw. A good sacrifice had been met by a good counter-sack.

xe6 9 h3 g5!, to draw. A good sacrifice had been met by a good counter-sack.

This sacrifice occurs in two forms of the Sicilian Defense. In one, Black plays … d5 in answer to g2-g4. We examined that in Chapter One.

The second version arises when Black’s pawn is at e5, not e6. Then when … d5 is met by exd5, Black may be able to liberate his pent-up power with … e4.

Petrosian – Smyslov

Moscow 1949

Black to play

If White can threaten the d-pawn with  fd2, Black’s bishops suffer after …

fd2, Black’s bishops suffer after …  e7 or …

e7 or …  c6. White would be at least equal. So Black chose 1 … d5!.

c6. White would be at least equal. So Black chose 1 … d5!.

White cannot allow … dxe4, e.g. 2  f3 dxe4 3

f3 dxe4 3  xd8+

xd8+  xd8 4

xd8 4  xe4??

xe4??  xe4 5

xe4 5  xe4

xe4  d1+.

d1+.

In the game, he chose 2  xd5?. This turned out badly following 2 …

xd5?. This turned out badly following 2 …  xd5 3 exd5

xd5 3 exd5  xc2 and then 4 b3 e4!. Black kept his pawn and it grew in power with 5 g4 e3 6

xc2 and then 4 b3 e4!. Black kept his pawn and it grew in power with 5 g4 e3 6  g2

g2  d2! 7

d2! 7  xd2 exd2 8

xd2 exd2 8  d1

d1  xd5. He won.

xd5. He won.

But what if White played 2 exd5 ? The answer is 2 … e4!.

White to play

The only way to avoid 3 …  xc3 4 bxc3

xc3 4 bxc3  xc3, which favors Black, is 3

xc3, which favors Black, is 3  xe4. But the Black bishops take over after 3 …

xe4. But the Black bishops take over after 3 …  xb2 and 4

xb2 and 4  f3

f3  xa3.

xa3.

If … d5 can be carried off favorably in an endgame like that, it stands to reason that it should be a worthy option in a middlegame:

Bokuchava – Tal

Poti 1970

Black to play

White has taken steps ( d2,

d2,  f3) to make sure …

f3) to make sure …  xc3 will be unsound. But 1 … d5! is promising. The main line is 2 exd5 e4!.

xc3 will be unsound. But 1 … d5! is promising. The main line is 2 exd5 e4!.

White’s bishop is not trapped because 3  fe1 exf3 allows 4

fe1 exf3 allows 4  xe8. Therefore, play could go 3

xe8. Therefore, play could go 3  fe1

fe1  e5 and then 4

e5 and then 4  xe4

xe4  xe4 5

xe4 5  xe4

xe4  xd5.

xd5.

There would be chances for both sides after 6  f4 and then 6 …

f4 and then 6 …  xe4 7

xe4 7  xe4

xe4  xc2 and 8

xc2 and 8  g3 f6 or 8

g3 f6 or 8  d4

d4  c4.

c4.

But back at the diagram White met 1 … d5 with 2  xd5? and Black replied 2 …

xd5? and Black replied 2 …  xd5 3 exd5 e4. On 4

xd5 3 exd5 e4. On 4  xe4 White just loses a piece.

xe4 White just loses a piece.

He tried 4  fe1

fe1  e5 5

e5 5  f4 but lost after 5 … exf3 6

f4 but lost after 5 … exf3 6  xe5

xe5  g4 (or 6

g4 (or 6  xe5

xe5  g4).

g4).

This is another sacrifice that can be carried out by White or Black. A rook is almost always given up for a bishop, not a knight. The compensation often comes in the form of domination of light or dark squares, depending on which bishop is captured.

Polugayevsky – Petrosian

Moscow 1983

Black to play

White might feel he is better because of his bishops and pressure ( b3,

b3,  fb1) against b7. But that changed radically after 1 …

fb1) against b7. But that changed radically after 1 …  xe3! 2 fxe3

xe3! 2 fxe3  c5.

c5.

The two-bishop edge is gone, b7 is rock solid and Black is preparing to target e3 and dominate the dark squares.

For example, 3  c1

c1  e8 4

e8 4  f3

f3  h6 and 5 …

h6 and 5 …  e7 threatens to win a pawn with …

e7 threatens to win a pawn with …  xe3+. If White tries to keep his material edge with

xe3+. If White tries to keep his material edge with  f2, Black can repeat the position with …

f2, Black can repeat the position with …  e4+ – but may want more.

e4+ – but may want more.

White preferred 3  c2

c2  e8. He should have conceded the e-pawn with 4

e8. He should have conceded the e-pawn with 4  b1

b1  xe3 5

xe3 5  be1. If White can trade a pair of rooks he would reach rough equality. But he chose 4

be1. If White can trade a pair of rooks he would reach rough equality. But he chose 4  f3

f3  h6 5

h6 5  c3

c3  e7 instead.

e7 instead.

White to play

Now 6  f2??

f2??  e4+ is out of the question. On other moves Black would enjoy slightly better chances after …

e4+ is out of the question. On other moves Black would enjoy slightly better chances after …  xe3+.

xe3+.

White blundered, however, with 6  b6? and resigned after 6 …

b6? and resigned after 6 …  a4!.

a4!.

The colors-reversed version, when White plays  xe6, often begins a kingside attack directed at squares around f7.

xe6, often begins a kingside attack directed at squares around f7.

Adorjan – Vadasz

Hungary 1970

Black to play

Since 1 …  g4 invites 2

g4 invites 2  e5!, Black tried 1 …

e5!, Black tried 1 …  e6. But this innocuous-looking move turned out to be a serious error because of 2

e6. But this innocuous-looking move turned out to be a serious error because of 2  xe6!.

xe6!.

White’s immediate aim is to win a pawn after 2 … fxe6 3  e1.

e1.

But he also had attacking chances based on  e5 or

e5 or  g5 – as well as on

g5 – as well as on  h6/

h6/ g5 and then either

g5 and then either  xg6 or

xg6 or  c4.

c4.

The dangers to Black were evident after 3 … c5 4  c4!

c4!  d5 and 5

d5 and 5  h6.

h6.

Black to play

Black’s position would be in free fall after 5 …  h8 6

h8 6  g5 and

g5 and  xe6 or

xe6 or  xe6. Also, after 5 …

xe6. Also, after 5 …  f6 6

f6 6  g5

g5  xg5 7

xg5 7  xg5 and

xg5 and  e5 or

e5 or  xg6.

xg6.

He played 5 …  ad8? 6

ad8? 6  xg7

xg7  xg7 7

xg7 7  g5

g5  c7 8

c7 8  f4. In this lost position he walked into 8 …

f4. In this lost position he walked into 8 …  f8 9

f8 9  xc7! (9 …

xc7! (9 …  xc7 10

xc7 10  xe6+ and

xe6+ and  xc7).

xc7).

Many of the rules given to beginners are so general (‘Don’t lose time in the opening’) that they’re almost useless. One of the most specific concerns a sacrifice: ‘Do not take the enemy b-pawn with your queen.’ There are good reasons for this.

Tal – Tringov

Amsterdam 1964

White to play

The game is five moves old and Black is already threatening to violate the rule with …  xb2. White played 1

xb2. White played 1  d2!

d2!  xb2 2

xb2 2  b1 and then 2 …

b1 and then 2 …  a3 3

a3 3  c4. His compensation is having six pieces in play in a semi-open position while Black is trying to fight with two.

c4. His compensation is having six pieces in play in a semi-open position while Black is trying to fight with two.

After 3 …  a5 4 0-0 Black should have developed, such as with 4 …

a5 4 0-0 Black should have developed, such as with 4 …  d7. But he played 4 … e6 and 5

d7. But he played 4 … e6 and 5  fe1 a6? 6

fe1 a6? 6  f4 e5 7 dxe5 dxe5.

f4 e5 7 dxe5 dxe5.

White to play

It shouldn’t be shocking that White can begin a sham sacrifice – that is, a combination – with 8  d6!. Then 8 … exf4 9

d6!. Then 8 … exf4 9  d5! cxd5 10 exd5+ loses and 9 …

d5! cxd5 10 exd5+ loses and 9 …  d7 10

d7 10  g5

g5  e5 11

e5 11  c7+!

c7+!  xc7 12

xc7 12  xf7+

xf7+  d8 13

d8 13  e6 is mate.

e6 is mate.

Black accepted a different sacrifice, 8 …  xc3, and resigned after 9

xc3, and resigned after 9  ed1

ed1  d7 10

d7 10  xf7+!

xf7+!  xf7 11

xf7 11  g5+

g5+  e8 12

e8 12  e6+ because of 12 …

e6+ because of 12 …  d8 13

d8 13  f7+

f7+  c7 14

c7 14  d6 mate or 12 …

d6 mate or 12 …  e7 13

e7 13  f7+

f7+  d8 14

d8 14  e6 mate.

e6 mate.

This sacrifice is offered so often because the best way to punish an early move of the enemy QB is to attack the undefended b-pawn. This occurs in openings as varied as the Sicilian’s Poisoned Pawn Variation (1 e4 c5 2  f3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4

f3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4  xd4

xd4  f6 5

f6 5  c3 a6 6

c3 a6 6  g5 e6 7 f4

g5 e6 7 f4  b6) and the Slav Defense (1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3

b6) and the Slav Defense (1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3  f3

f3  f6 4

f6 4  c3

c3  f5 5 cxd5 cxd5 6

f5 5 cxd5 cxd5 6  b3!).

b3!).

The compensation is usually just a lead in development. But the sacrificer usually needs to open the center to make that matter. For example, 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 e5 c5 4 dxc5  c6 5

c6 5  f3

f3  xc5 6

xc5 6  d3

d3  ge7 7

ge7 7  f4

f4  b6.

b6.

Keres – Alexandrescu

Munich 1936

White to play

White played this way for several reasons. First, the conservative 7 0-0  g6! would have posed problems defending the e-pawn, e.g. 8

g6! would have posed problems defending the e-pawn, e.g. 8  e1

e1  d7 followed by …

d7 followed by …  b6-c7.

b6-c7.

The sacrifice, 8 0-0  xb2, made sense because (a) it costs Black two tempi to grab the pawn and bring his queen to safety, (b) White can open the center with c2-c4!, and (c) Black won’t be able to castle easily because of tactics.

xb2, made sense because (a) it costs Black two tempi to grab the pawn and bring his queen to safety, (b) White can open the center with c2-c4!, and (c) Black won’t be able to castle easily because of tactics.

Play went 9  bd2

bd2  b6 10 c4!. Note that 10 … 0-0 is no good because of 11

b6 10 c4!. Note that 10 … 0-0 is no good because of 11  xh7+!

xh7+!  xh7 12

xh7 12  g5+

g5+  g8 13

g8 13  h5 or 12 …

h5 or 12 …  g6 13

g6 13  g4.

g4.

Therefore Black played 10 … h6, But White replied 11  c1!.

c1!.

Black to play

He threatens 12  b1

b1  d8 (12 …

d8 (12 …  a5 13

a5 13  b3) 13 cxd5

b3) 13 cxd5  xd5 14

xd5 14  e4 and

e4 and  xc5 when the queen retreats. And he’s also looking to play

xc5 when the queen retreats. And he’s also looking to play  xh6.

xh6.

Black was forced into unnatural moves, 11 …  b4 12

b4 12  e2

e2  d7 13 a3

d7 13 a3  a6 14

a6 14  b1

b1  c6.

c6.

He was in trouble after 15  g3

g3  f5 16 cxd5 exd5 17 e6! because of 17 …

f5 16 cxd5 exd5 17 e6! because of 17 …  xe6?? 18

xe6?? 18  b5.

b5.

He lost quickly: 17 … fxe6 18  e5

e5  xg3 19 hxg3

xg3 19 hxg3  c7 20

c7 20  xd7

xd7  xd7 21

xd7 21  b2

b2  b6 22

b6 22  xg7+

xg7+  d6 23

d6 23  e4+! dxe4 24

e4+! dxe4 24  fd1+ resigns.

fd1+ resigns.

But the b-pawn is not poisoned in other cases, as the success of 1 d4  f6 2

f6 2  f3 e6 3

f3 e6 3  g5 c5 4 e3

g5 c5 4 e3  b6 5

b6 5  bd2

bd2  xb2!? and other openings have shown. Understanding what makes the sacrifice work – such as opening the center – is part of a master’s know how.

xb2!? and other openings have shown. Understanding what makes the sacrifice work – such as opening the center – is part of a master’s know how.

When the center is locked thanks to Black pawns at c5, d6 and e5, the action typically turns to the wings. But a sacrifice of a piece on c5 or e5 can make an explosive difference.

Spassky – Penrose

Palma de Mallorca 1969

White to play

White has better pieces but the closed center stifles them. He would have little after 1  f5

f5  xf5 2 exf5 and 2 …

xf5 2 exf5 and 2 …  g7 and …

g7 and …  f6, for example.

f6, for example.

White’s solution was 1  xc5! dxc5 2

xc5! dxc5 2  xe5. His aim is e4-e5, which frees e4 for a piece and can make threats of d5-d6 or e5-e6. On 2 …

xe5. His aim is e4-e5, which frees e4 for a piece and can make threats of d5-d6 or e5-e6. On 2 …  d6 he should avoid the endgame (3

d6 he should avoid the endgame (3  xd6

xd6  xd6 4 e5

xd6 4 e5  f7) and continue 3

f7) and continue 3  a1!.

a1!.

The game went 2 …  g8 and 3

g8 and 3  b8.

b8.

Black to play

Now 4 e5 can’t be stopped. Then White’s minor pieces take over, e.g. 5  e4+, 5

e4+, 5  e4 and 6

e4 and 6  xc5 or 5

xc5 or 5  f5 followed by 6 e6.

f5 followed by 6 e6.

Black’s reply, 3 …  ef6, prepared to give back the piece, 4 e5

ef6, prepared to give back the piece, 4 e5  xd5! 5 cxd5

xd5! 5 cxd5  xd5, when chances would be equal.

xd5, when chances would be equal.

But White found 4  f5 and then 4 …

f5 and then 4 …  e7 5

e7 5  xh6!. This is based on 5 …

xh6!. This is based on 5 …  xh6 6

xh6 6  f8+ followed by 7

f8+ followed by 7  f7+, 8

f7+, 8  xf6+ and a winning e4-e5.

xf6+ and a winning e4-e5.

Black decided on 5 …  exd5 6 cxd5

exd5 6 cxd5  xh6. But after 7

xh6. But after 7  f8+

f8+  g7 8

g7 8  xc5 the center pawns could no longer be restrained.

xc5 the center pawns could no longer be restrained.

The game ended with 8 …  d7 9

d7 9  d6+

d6+  h7 10 e5!

h7 10 e5!  h8 (10 …

h8 (10 …  xe5 11

xe5 11  e4+

e4+  g8 12

g8 12  b8+) 11 h6

b8+) 11 h6  h7 12 e6!

h7 12 e6!  c2+ 13

c2+ 13  g3 resigns.

g3 resigns.

Because of Black’s tight quarters in the full Benoni pawn structure, it’s often impossible for him to stop the sacrifice. The best defense may be a counter-sacrifice as he tried in the last example and more successfully in the next.

Gufeld – Augustin

Sochi 1979

White to play

This arose from a Ruy Lopez, not a Benoni. After 1  xe5! dxe5 2

xe5! dxe5 2  xc5 White would pocket the b4-pawn and have a huge pawn roller.

xc5 White would pocket the b4-pawn and have a huge pawn roller.

For example, 2 …  c8 3

c8 3  xf8

xf8  xf8 4

xf8 4  xb4 followed by c4-c5 and maybe

xb4 followed by c4-c5 and maybe  d3,

d3,  c3 and b3-b4-b5.

c3 and b3-b4-b5.

But White preferred 1  xc5 dxc5 2

xc5 dxc5 2  xe5. When Black prevented 3

xe5. When Black prevented 3  xf7+ by means of 2 …

xf7+ by means of 2 …  g8, White continued 3

g8, White continued 3  xd7

xd7  xd7 4 e5.

xd7 4 e5.

Black to play

This looks ominous because of 5 d6  g6 6 e6 or 5 …

g6 6 e6 or 5 …  c6 6

c6 6  d3, threatening mate on h7.

d3, threatening mate on h7.

But Black found safety in 4 …  xd5! 5 cxd5

xd5! 5 cxd5  xe5 and then 6

xe5 and then 6  xe5

xe5  xe5.

xe5.

Material is equal and 7 f4  d7 8

d7 8  e4 allowed him to flee into a bishops-of-opposite-color ending, 8 …

e4 allowed him to flee into a bishops-of-opposite-color ending, 8 …  a1+ 9

a1+ 9  f2

f2  d4+! 10

d4+! 10  xd4 cxd4 11 f5

xd4 cxd4 11 f5  f6! 12

f6! 12  xf6+ gxf6, that was ultimately drawn.

xf6+ gxf6, that was ultimately drawn.

When White pushes his unsupported g-pawn two squares he dares Black to take it. If Black doesn’t, White saves a tempo for his attack – and an extra tempo often makes an attack decisive.

Spassky – Petrosian

World Championship 1969

White to play

A priyome in similar positions is 1 e5. But White chose 1 g4! because it prepares a powerful push to g5 and g6, e.g. 1 … b5 2 g5! hxg5 3 fxg5  d7 5 g6! or 4 …

d7 5 g6! or 4 …  h5 5 g6! fxg6 6

h5 5 g6! fxg6 6  g5.

g5.

So Black played 1 …  xg4 and then came 2

xg4 and then came 2  g2

g2  f6 3

f6 3  g1. White’s ideas include (a) f4-f5, (b)

g1. White’s ideas include (a) f4-f5, (b)  f3 and e4-e5, and (c)

f3 and e4-e5, and (c)  d3-g3 and

d3-g3 and  xg7+.

xg7+.

Black defended with 3 …  d7 4 f5

d7 4 f5  g8, because 4 … e5 5

g8, because 4 … e5 5  de2 and 6

de2 and 6  g6! would have been too strong. White continued to build up, 5

g6! would have been too strong. White continued to build up, 5  df1.

df1.

Black to play

Now 5 … e5 is bad because of 6  e6! fxe6 7 fxe6

e6! fxe6 7 fxe6  xe6 and 8

xe6 and 8  xf6!, threatening 9

xf6!, threatening 9  xf8+!

xf8+!  xf8 10

xf8 10  xg7 mate.

xg7 mate.

Black should have tried 5 … exf5! 6  xf5

xf5  xf5. But he allowed 5 …

xf5. But he allowed 5 …  d8? 6 fxe6 fxe6 7 e5!, a sacrifice we’ll examine in a few pages.

d8? 6 fxe6 fxe6 7 e5!, a sacrifice we’ll examine in a few pages.

After 7 … dxe5 8  e4 White threatened to take on f6. He would meet 8 …

e4 White threatened to take on f6. He would meet 8 …  xe4 with 9

xe4 with 9  xf8+! and 10

xf8+! and 10  xg7 mate. The rest: 8 …

xg7 mate. The rest: 8 …  h5 9

h5 9  g6 exd4 10

g6 exd4 10  g5! Resigns. (11 … hxg5 12

g5! Resigns. (11 … hxg5 12  xh5+

xh5+  g8 13

g8 13  f7+

f7+  h8 14

h8 14  f3 and mate).

f3 and mate).

The g2-g4 push is not exclusive to Sicilian bashers. It crops up in Caro-Kann Defense middlegames and 1 d4 openings like the Semi-Slav (1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3  c3

c3  f6 4

f6 4  f3 c6 5 e3

f3 c6 5 e3  bd7 6

bd7 6  c2

c2  d6 7 g4

d6 7 g4  xg4 8

xg4 8  g1) and various Indian defenses, like 1 d4

g1) and various Indian defenses, like 1 d4  f6 2 c4 d6 3

f6 2 c4 d6 3  c3 e5 4

c3 e5 4  f3

f3  bd7 5 e4

bd7 5 e4  e7 6

e7 6  e2 0-0 7 g4!?

e2 0-0 7 g4!?  xg4 8

xg4 8  g1. Here’s a vintage example from a Semi-Slav.

g1. Here’s a vintage example from a Semi-Slav.

Alekhine – Illa

Buenos Aires 1926

White to play

With 1 g4! White tried to force half of the g-file open. On 1 …  xg4 he would gain time with 2

xg4 he would gain time with 2  dg1

dg1  h5 3

h5 3  g5

g5  h3. He might win after 4

h3. He might win after 4  hg1 g6 5 c5

hg1 g6 5 c5  e7 6

e7 6  e5 followed by

e5 followed by  xg6.

xg6.

But what if Black takes with his knight, 1 …  xg4 and 2 c5

xg4 and 2 c5  c7 ? Once again the file is dangerous after 3

c7 ? Once again the file is dangerous after 3  hg1. Black was clinging to life after 3 … f5 4

hg1. Black was clinging to life after 3 … f5 4  e5 because 4 …

e5 because 4 …  xe5 5 dxe5 threatens 6 f3 (5 …

xe5 5 dxe5 threatens 6 f3 (5 …  f6 6

f6 6  xg7+!).

xg7+!).

Instead he chose 4 …  f6 and White won with 5 f3

f6 and White won with 5 f3  xe5 6

xe5 6  xe5

xe5  e8 7

e8 7  g5

g5  f7 8

f7 8  xf5! (8 … exf5 9

xf5! (8 … exf5 9  b3).

b3).

A colors-reversed form of the g2-g4 sacrifice is … b5 by Black when White has castled queenside. If the pawn is not captured it can become a battering ram.

Abu Sufian – Lalic

Hastings 2007-08

Black to play

Black has a space edge on the queenside but it looks like White has the quicker attack. This appearance changed after 1 … b5!.

Then on 2  xb5

xb5  b8 Black would hold the initiative, 3

b8 Black would hold the initiative, 3  d6

d6  xd6 4 exd6 and 4 …

xd6 4 exd6 and 4 …  b4 5

b4 5  b1

b1  f6 and …

f6 and …  e4, for example.

e4, for example.

In the game White ignored the offer with 2 fxe6 fxe6 3 h4. But he was soon overwhelmed by 3 …  a5 4

a5 4  g5 b4!.

g5 b4!.

xe6) for Pawns

xe6) for PawnsAnother common feature of Sicilian Defenses is a White sacrifice on e6. Ideally he gets three pawns – and an attack – for a bishop.

Stein – Chistyakov

Soviet Team Championship 1959

White to play

Black has just retreated his attacked knight to d7. But this allowed 1  xe6!. Then 1 …

xe6!. Then 1 …  xd4 loses a pawn to 2

xd4 loses a pawn to 2  xd7+ and 3

xd7+ and 3  xd4.

xd4.

Play went 1 … fxe6 2  xe6. Black had to move his attacked queen and give up a third pawn, 2 …

xe6. Black had to move his attacked queen and give up a third pawn, 2 …  a5 3

a5 3  xg7+.

xg7+.

White’s pawns provide cover for attacking pieces, e.g. 3 …  f7 4

f7 4  f5

f5  f8 5

f8 5  h5+

h5+  g8? 6

g8? 6  h6+ mates or 5 …

h6+ mates or 5 …  g6 6

g6 6  xe7

xe7  xe7 6

xe7 6  d2 and

d2 and  d5+.

d5+.

Black tried 3 …  f8 4

f8 4  e6+

e6+  g8 but was losing after 5

g8 but was losing after 5  h5

h5  f8 6

f8 6  xf8

xf8  xf8 7

xf8 7  d2 with a threat of 8

d2 with a threat of 8  d5 followed by

d5 followed by  f6+ or

f6+ or  xa5.

xa5.

When White would get three pawns and strong attacking chances from  xe6, it may pay to decline the offer. For instance: 1 e4 c5 2

xe6, it may pay to decline the offer. For instance: 1 e4 c5 2  f3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4

f3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4  xd4

xd4  f6 5

f6 5  c3 a6 6

c3 a6 6  c4 e6 7

c4 e6 7  b3

b3  e7 8 f4 b5 9 e5! dxe5 10 fxe5

e7 8 f4 b5 9 e5! dxe5 10 fxe5  fd7.

fd7.

White to play

When White opts for 11  xe6 Black should avoid 11 … fxe6 12

xe6 Black should avoid 11 … fxe6 12  xe6

xe6  b6? 13

b6? 13  d5 or 12 …

d5 or 12 …  a5 13

a5 13  xg7+.

xg7+.

He has better chances of survival after 11 …  xe5! even if White has the upper hand following 12

xe5! even if White has the upper hand following 12  xc8 and 13

xc8 and 13  d5.

d5.

Rudolf Spielmann loved all kinds of sacrifices but he is particularly associated with the advance of an e-pawn to the sixth rank. One of his games began 1 e4  f6 2

f6 2  c3 d5 3 e5

c3 d5 3 e5  fd7 4 e6!?. The point is that 4 … fxe6 5 d4 makes a mess of Black’s pawn structure.

fd7 4 e6!?. The point is that 4 … fxe6 5 d4 makes a mess of Black’s pawn structure.

Black to play

The safest policy may be to return the pawn, 5 … e5 6 dxe5 e6, but this is not to everyone’s taste. Black played 5 …  f6?! 6

f6?! 6  f3 c5 7 dxc5

f3 c5 7 dxc5  c6 and lost quickly after 8

c6 and lost quickly after 8  b5!

b5!  d7 9 0-0

d7 9 0-0  c7 11

c7 11  e1 (threat of

e1 (threat of  g5xe6) h6 12

g5xe6) h6 12  xc6 bxc6 13

xc6 bxc6 13  e5.

e5.

This obstruction idea occurs in many different openings. Another of Spielmann’s games began 1 e4 c6 2  c3 d5 3

c3 d5 3  f3

f3  f6?! 4 e5

f6?! 4 e5  e4 5

e4 5  e2

e2  xc3 6 dxc3 b6?! 7

xc3 6 dxc3 b6?! 7  d4 c5? and then 8 e6!.

d4 c5? and then 8 e6!.

If Black can’t correct his pawn structure, he needs active counterplay, as in this example from a King’s Indian Defense.

Black to play

If Black retreats 1 …  e8, he is worse after, say, 2 cxb5 axb5 3

e8, he is worse after, say, 2 cxb5 axb5 3  f4 and

f4 and  e4. His choice is between 1 …

e4. His choice is between 1 …  d7 or an exchange of pawns and queens first. In either case White cannot maintain his pawn on e5.

d7 or an exchange of pawns and queens first. In either case White cannot maintain his pawn on e5.

If Black opts for the middlegame, 1 …  d7?! 2 e6! he faces dangers like 2 … fxe6 3 d5!, when 3 … exd5 4 cxb5 axb5? 5

d7?! 2 e6! he faces dangers like 2 … fxe6 3 d5!, when 3 … exd5 4 cxb5 axb5? 5  xd5+ costs a piece. Or 3 …

xd5+ costs a piece. Or 3 …  a5 4 cxb5 exd5 5

a5 4 cxb5 exd5 5  d4 and 3 …

d4 and 3 …  a7 4 dxe6.

a7 4 dxe6.

Experience indicates White has compensation in the endgame, after 1 … dxe5 2 dxe5  xd1 3

xd1 3  xd1

xd1  d7, in view of 4 e6! fxe6 5 cxb5 axb5 6

d7, in view of 4 e6! fxe6 5 cxb5 axb5 6  f4.

f4.

Black to play

Black is worse after 6 … e5? 7  e3. For example, 7 …

e3. For example, 7 …  f6 8

f6 8  ac1

ac1  d7 and now both 9

d7 and now both 9  e4 followed by

e4 followed by  c5 and 9

c5 and 9  d5

d5  xd5 10

xd5 10  xd5 are good.

xd5 are good.

As in the Spielmann games, Black’s downfall comes from passive play. In the diagram, 6 … b4 7  a4

a4  b6! is a fine, forcing idea, e.g. 8

b6! is a fine, forcing idea, e.g. 8  xb6

xb6  xb6 9

xb6 9  xc7

xc7  b7 and 10 …

b7 and 10 …  xb2.

xb2.

d5

d5Planting a knight on d5 is a common sacrifice in English Opening and Sicilian Defense middlegames. It works when the virtually forced … exd5 allows White to build pressure on a newly opened file.

Uhlmann – Brameyer

East German Championship 1972

White to play

White began with 1  d5! because 1 …

d5! because 1 …  b8? 2

b8? 2  xc6 and 3

xc6 and 3  xe7+ or 1 …

xe7+ or 1 …  d7? 2

d7? 2  b6 are verboten.

b6 are verboten.

Black played 1 … exd5 2 cxd5 and 2 …  xd5 3

xd5 3  xd5. Thanks to the sham sacrifice White pressures c6. The game ended quickly: 3 …

xd5. Thanks to the sham sacrifice White pressures c6. The game ended quickly: 3 …  d7 4

d7 4  d3

d3  b6 and 5

b6 and 5  f5

f5  f8? and 6

f8? and 6  xc6! bxc6 7

xc6! bxc6 7  h6+! gxh6 8

h6+! gxh6 8  c3 and mates.

c3 and mates.

In the Sicilian, a sacrifice on d5 is more often real, rather than sham, and is typically designed to open the e-file when the enemy king is uncastled. Here’s a case of White offering pieces twice on d5.

Tal – Mukhin

Baku 1972

White to play

After 1  d5! Black rejected 1 … exd5 2 exd5+ because 2 …

d5! Black rejected 1 … exd5 2 exd5+ because 2 …  e7 3

e7 3  f5 loses back the piece and 2 …

f5 loses back the piece and 2 …  d7 3 b4 or 3

d7 3 b4 or 3  c6 gives White excellent compensation. For example, 3 b4

c6 gives White excellent compensation. For example, 3 b4  a4 4

a4 4  xa4 bxa4 5 c4 and

xa4 bxa4 5 c4 and  xa4+.

xa4+.

So he chose 1 … b4, expecting the knight to retreat from c3. But White fired back 2  xb7

xb7  xb7 and 3

xb7 and 3  d5!.

d5!.

Black had little choice this time in view of 3 …  e7? 4

e7? 4  c6 or 3 … a5? 4

c6 or 3 … a5? 4  xf6 gxf6 5

xf6 gxf6 5  c6!

c6!  c8 6

c8 6  xf6 mate.

xf6 mate.

So the game went 3 … exd5 4 exd5+ and 4 …  d7 – again avoiding 4 …

d7 – again avoiding 4 …  e7? 5

e7? 5  f5.

f5.

White to play

White has one pawn for his knight but Black’s king predicament and the prospect of  c6 offers excellent ‘comp.’ White chose 5 c3 because 5 … bxc3 6

c6 offers excellent ‘comp.’ White chose 5 c3 because 5 … bxc3 6  a4+ and 7

a4+ and 7  ac1! would open decisive attacking lines.

ac1! would open decisive attacking lines.

So play went 5 … b3 6  xb3

xb3  c5 7

c5 7  c4 with 8 b4 or 8

c4 with 8 b4 or 8  c6 coming up, e.g. 7 …

c6 coming up, e.g. 7 …  c8 8 b4

c8 8 b4  ce4 is met by 9

ce4 is met by 9  c6

c6  xg5 10

xg5 10  b8+!

b8+!  xb8 11

xb8 11  c6 mate.

c6 mate.

Instead, Black tried 7 …  c8 8

c8 8  c6 and White was threatening 9

c6 and White was threatening 9  e3 followed by

e3 followed by  ae1 and

ae1 and  e3 and

e3 and  e7+!.

e7+!.

The game ended with 8 … h6 9  xf6 gxf6 10

xf6 gxf6 10  e3

e3  c7 11 b4

c7 11 b4  g8? and Black resigned.

g8? and Black resigned.

It’s a familiar scenario: Kings are castled on opposite wings and the player who first opens attacking lines wins. He may have done it with a supported pawn charge. But quicker is an unsupported charge, that is, a sacrifice.

White to play

White’s attack seems to be on schedule with 1 h5 followed by 2  h3 or 2

h3 or 2  d3 and 3

d3 and 3  dg1/ 4 g6.

dg1/ 4 g6.

But Black can interrupt him with the forcing 1 … b4!. That seizes the initiative, 2  a4

a4  c5! 3

c5! 3  axc5 dxc5, and White’s attack grinds to a halt. Or 2

axc5 dxc5, and White’s attack grinds to a halt. Or 2  e2

e2  de5 threatening 3 …

de5 threatening 3 …  xf3 and 3 …

xf3 and 3 …  c4.

c4.

White doesn’t need to support his g-pawn. With the faster 1 g6! he threatens 2 gxf7+  xf7. Then he can choose between 3

xf7. Then he can choose between 3  h3, with

h3, with  xe6+ in mind, and 3 f4/4 f5.

xe6+ in mind, and 3 f4/4 f5.

And what if the pawn is taken? One way is 1 … hxg6 and then 2 h5! gxh5 3  xh5 with deadly play on the open file (3 …

xh5 with deadly play on the open file (3 …  f6 4

f6 4  h3 and

h3 and  h2).

h2).

Only slightly better is 1 … fxg6 2 h5! gxh5 3  xh5 and 3 …

xh5 and 3 …  f6 4

f6 4  g5.

g5.

Black to play

Now the target is g7. For example, 4 …  e5 5

e5 5  g2

g2  f8 and 6

f8 and 6  e2 followed by f3-f4 with a terrific attack for White.

e2 followed by f3-f4 with a terrific attack for White.

While White is looking to his right in this kind of position, Black can look to his right – to open a queenside file with a very similar sacrifice.

Ilincic – Cvetkovic

Kladovo 1990

Black to play

White is on the verge of g5-g6 while Black has a hard time preparing a supported … b3 – since 1 … a4 allows 2  xb4.

xb4.

But Black doesn’t have to prepare. He stole the initiative with 1 … b3!, even though the pawn can be taken three ways.

The simplest lines are 2  xb3

xb3  xf3! and 2 cxb3

xf3! and 2 cxb3  c8+ 3

c8+ 3  b1

b1  xf3! (4

xf3! (4  xf3

xf3  xe4+ and …

xe4+ and …  xf3), which favor Black.

xf3), which favor Black.

The real test was 2 axb3. Black continued 2 … a4!. It’s the mirror image of what happened on the kingside in the previous example, when White played g5-g6 and met … hxg6 with h4-h5!.

After 2 … a4, White tried to keep files closed with 3 b4. But on 3 … a3 4 b3 Black would have opened the position with 4 … d5!.

Instead, after 3 … a3 White went for 4  b1 axb2 5

b1 axb2 5  xb2.

xb2.

Black to play

At the cost of a pawn Black has the more vulnerable king target. Next came 5 … d5!, getting his e7-bishop into play and readying …  a4/…

a4/…  a8. If 6 cxd5

a8. If 6 cxd5  xd5 he would threaten 7 …

xd5 he would threaten 7 …  a2+ and 7 …

a2+ and 7 …  xf3.

xf3.

White tried to close the position with 6 c3 dxe4 7 f4. But Black replied 7 …  d5 8

d5 8  b3

b3  d3+ 9

d3+ 9  xd3 exd3. He won eventually after 10

xd3 exd3. He won eventually after 10  hg1

hg1  xb3 11

xb3 11  xb3

xb3  xb4! since 12 cxb4

xb4! since 12 cxb4  d5+ is death.

d5+ is death.

The sacrifices in this chapter tend to fall into two categories: There are those that wouldn’t occur to amateurs because they just seem so strange, such as the ‘impossible’ d4-d5 push and the Exchange sacks on e6 or f3. A second group of sacrifices are trade secrets because amateurs think the key moves require preparation: They feel that g5-g6 needs h4-h5. Others of this type are the unsupported g2-g4 advance, the Benko-like … b5 – and Emanuel Lasker’s contribution to the science of sacrifice.

Lasker made this sacrifice famous when he cleared a square for his knight at e4 in a famous endgame against Jose Capablanca, at St. Petersburg 1914. The push is much more common in a middlegame.

Ragozin – Noskov

Leningrad 1930

White to play

Black’s last move, …  f6, was designed to neutralize the b2-g7 diagonal. He may have counted on being safe after 1

f6, was designed to neutralize the b2-g7 diagonal. He may have counted on being safe after 1  xf6

xf6  xf6 and 2 … e5. Then he could meet 2 e5 dxe5 3 fxe5 with 3 …

xf6 and 2 … e5. Then he could meet 2 e5 dxe5 3 fxe5 with 3 …  d4+ and 4 …

d4+ and 4 …  xe5.

xe5.

But White played the immediate 1 e5! and 1 … dxe5 2  e4!. If Black refuses the pawn, 2 …

e4!. If Black refuses the pawn, 2 …  e7 3 fxe5

e7 3 fxe5  c5, White’s attack wins with 4

c5, White’s attack wins with 4  f6+! gxf6 5

f6+! gxf6 5  g4+

g4+  h8 6 exf6. Or 3 …

h8 6 exf6. Or 3 …  h8 4

h8 4  xh7

xh7  xd3 5

xd3 5  h5

h5  g8 6 cxd3.

g8 6 cxd3.

Black tried 2 … exf4 and then 3  xf6+

xf6+  xf6 4

xf6 4  xf4:

xf4:

Black to play

Now  xf6 or

xf6 or  xf6 are on tap, and 4 …

xf6 are on tap, and 4 …  d5 would invite a sham sacrifice, 5

d5 would invite a sham sacrifice, 5  xh7+!

xh7+!  xh7 6

xh7 6  h5+

h5+  g8 7

g8 7  xg7!

xg7!  xg7 8

xg7 8  g4+

g4+  f6 9

f6 9  g5 mate.

g5 mate.

Black can defend much better with 4 … e5! and 5  xe5

xe5  d5. Then the two-bishop sacrifice fails. White might try 6

d5. Then the two-bishop sacrifice fails. White might try 6  h5 h6 7

h5 h6 7  f3 instead.

f3 instead.

Instead, Black created an escape route for this king with 4 …  e8?. But this handed White another winning combination, 5

e8?. But this handed White another winning combination, 5  xf6! gxf6 6

xf6! gxf6 6  g4+.

g4+.

Black could resign after 6 …  h8 7

h8 7  h4. He chose 6 …

h4. He chose 6 …  f8 and lost after 7

f8 and lost after 7  a3+

a3+  e7 8

e7 8  xh7

xh7  b6+ 9

b6+ 9  h1

h1  e8 10

e8 10  d1! and

d1! and  g8 mate.

g8 mate.

Another common form arises when the sacrifice of the e-pawn prepares an advance of the f-pawn.

Short – Ni Hua

Beijing 2003

Black to play

White threatens  xf5 and would win control of light squares for his minor pieces after 1 … fxg4 2 fxg4 (or 1 … f4? 2

xf5 and would win control of light squares for his minor pieces after 1 … fxg4 2 fxg4 (or 1 … f4? 2  xh7).

xh7).

Black made the dark squares more important with 1 … e4!. If 2  e2, then 2 … exf3 and 3 …

e2, then 2 … exf3 and 3 …  e5 is annoying. (After 3

e5 is annoying. (After 3  xf3 Black might prefer 3 … fxg4 4

xf3 Black might prefer 3 … fxg4 4  xg4

xg4  xf1+ 5

xf1+ 5  xf1

xf1  xf1+.)

xf1+.)

White accepted the offer, 2 fxe4. But 2 … f4! revealed Black’s strategy: At the cost of a pawn he cleared e5 for his knight and obtained a powerful passed f-pawn. White’s bishop and knight, which would have been powerful after 1 … f4 or 1 … fxg4, have become idle spectators.

Play continued 3  e2 f3 4

e2 f3 4  d2

d2  e5. (Even better was 4 … f2!, threatening …

e5. (Even better was 4 … f2!, threatening …  f3 mate, and then 5

f3 mate, and then 5  e3

e3  e5 followed by 6 …

e5 followed by 6 …  xg4 or 6 …

xg4 or 6 …  f3+ 7

f3+ 7  xf3

xf3  xf3.)

xf3.)

White to play

Black’s knight and f-pawn allowed him time to mobilize both rooks and he was winning after 5 g5  g6 6

g6 6  g1

g1  g4 7

g4 7  b1

b1  f7 and …

f7 and …  af8.

af8.

By passive we mean a non-forcing move that leaves a piece en prise. Consider the Sicilian Defense line that runs 1 e4 c5 2  f3

f3  c6 3 d4 cxd4 4

c6 3 d4 cxd4 4  xd4

xd4  f6 5

f6 5  c3 d6 6

c3 d6 6  g5 e6 7

g5 e6 7  d2

d2  e7 8 0-0-0 0-0 and then 9 f4 h6:

e7 8 0-0-0 0-0 and then 9 f4 h6:

White to play

There are several reasons why Black wants to see 10  h4. He might prefer the bishop to be unprotected so that 10 …

h4. He might prefer the bishop to be unprotected so that 10 …  xe4 11

xe4 11  xe4

xe4  xh4.

xh4.

White has an alternative in 10 h4!?. The first point is that after 10 … hxg5 11 hxg5 he can swing his queen to the h-file and threaten mate on h7 or h8, e.g. 11 …  d7 12

d7 12  xc6 bxc6 13 g4 and

xc6 bxc6 13 g4 and  h2.

h2.

And on 10 …  xd4 11

xd4 11  xd4 hxg5 12 hxg5:

xd4 hxg5 12 hxg5:

Black to play

White can meet 12 …  g4 with 13

g4 with 13  e2 e5 14

e2 e5 14  g1! exf4 and 15

g1! exf4 and 15  xg4, with the idea of

xg4, with the idea of  h2-h8 mate.

h2-h8 mate.

Moreover, 10 h4 is not just based on the wishful thinking that Black will open the h-file. After 10 …  xd4 11

xd4 11  xd4 a6, for instance, White can aim for

xd4 a6, for instance, White can aim for  e2 and g2-g4-g5. This is stronger thanks to h2-h4. One GM game went 12

e2 and g2-g4-g5. This is stronger thanks to h2-h4. One GM game went 12  e2

e2  a5 13

a5 13  f3

f3  d8 14 g4!

d8 14 g4!  d7 and then 15

d7 and then 15  xh6 gxh6 16 g5 with a fierce attack that eventually won.

xh6 gxh6 16 g5 with a fierce attack that eventually won.

The prime virtue of this sacrifice is that it allows you to ignore … h6 when you really don’t want to retreat or trade the bishop. Here’s how a missed opportunity can ruin a game.

Saidy – Fischer

New York 1965

White to play

The pin on the knight at f6 and the threat of e4-e5 gave White compensation for his pawn. But Black’s last move, … h6, ‘put the question.’

White would be worse in the 1  xf6

xf6  xf6 2

xf6 2  xf6 gxf6 endgame.

xf6 gxf6 endgame.

He stayed in the middlegame with 1  d2 and 1 …

d2 and 1 …  bd7 2 e5

bd7 2 e5  d5. But he was worse and after 3

d5. But he was worse and after 3  f5? exf5! 4

f5? exf5! 4  xd5

xd5  e8 5

e8 5  xc4? he overlooked 5 …

xc4? he overlooked 5 …  xe5! 6

xe5! 6  xd8

xd8  xc4+! 7

xc4+! 7  xe8+

xe8+  xe8+. Black went on to win the ending after 8

xe8+. Black went on to win the ending after 8  d1

d1  xd2 9

xd2 9  xd2

xd2  e2+ 10

e2+ 10  c1

c1  xf2.

xf2.

White missed a chance to upset one of history’s greatest players because he didn’t know the passive sack, 1 h4!. If 1 … hxg5 2 hxg5 Black can’t move his knight because he faces death on the h-file. Moreover, White could build up his attack since he is no rush to take on f6. For example, 2 …  bd7 permits a strong 3 e5!.

bd7 permits a strong 3 e5!.

Well before the Benko Gambit (1 d4  f6 2 c4 c5 3 d5 b5!? 4 cxb5 a6), players on the Black side of a King’s Indian Defense or Benoni conjured counterplay by offering a pawn on b5:

f6 2 c4 c5 3 d5 b5!? 4 cxb5 a6), players on the Black side of a King’s Indian Defense or Benoni conjured counterplay by offering a pawn on b5:

Uhlmann – Geller

Palma de Mallorca 1970

Black to play

Black often plays … e6 and … exd5 in similar positions. But that would lose a pawn here (1 … e6 2 dxe6 and 3  xd6).

xd6).

Black found 1 … b5! and then 2 cxb5 axb5 3  xb5

xb5  b6. He can use the two half-open files to pressure pawns at a2 and b2.

b6. He can use the two half-open files to pressure pawns at a2 and b2.

He also threatens 4 …  xe4 5

xe4 5  xe4

xe4  xb5. In fact, after 4 a4 he still has 4 …

xb5. In fact, after 4 a4 he still has 4 …  xe4 5

xe4 5  xe4

xe4  xb5! because 6 axb5

xb5! because 6 axb5  xa1+ and …

xa1+ and …  xh1 favors him.

xh1 favors him.

White chose 4  e2 and Black attacked the e-pawn with 4 …

e2 and Black attacked the e-pawn with 4 …  b4!.

b4!.

White to play

The tactical problems are shown by 5  c2?

c2?  xe4 6

xe4 6  xe4??

xe4??  xc3+.

xc3+.

White liquidated pawns and pieces, 5 e5  h5 6

h5 6  g3 and then 6 …

g3 and then 6 …  a6! 7

a6! 7  xa6

xa6  xa6 8 exd6 exd6. Black prepared to pile on pressure with …

xa6 8 exd6 exd6. Black prepared to pile on pressure with …  d7-b6, …

d7-b6, …  b8 or

b8 or  fa8 and then either …

fa8 and then either …  a4 or …

a4 or …  c4.

c4.

The game saw 9 0-0  d7 10

d7 10  ae1

ae1  xg3 11 hxg3

xg3 11 hxg3  b6. Black’s threats include 12 …

b6. Black’s threats include 12 …  c4 and 12 …

c4 and 12 …  xc3 13 bxc3

xc3 13 bxc3  c4.

c4.

Something had to fall. And when it did, 12  e2

e2  c4 13

c4 13  d3

d3  fa8 14 b3

fa8 14 b3  xc3 15

xc3 15  xc3

xc3  xc3 16 bxc4

xc3 16 bxc4  xa2 17

xa2 17  xa2

xa2  xa2, Black had a better rook, better minor piece and, after his king reached f5, a better king. He won.

xa2, Black had a better rook, better minor piece and, after his king reached f5, a better king. He won.

The … b5 sacrifice typically occurs in the opening or early middlegame when Black can exploit a lead in development. If White can coordinate his pieces smoothly, the sacrifice may backfire. For example, 1 d4  f6 2 c4 g6 3

f6 2 c4 g6 3  c3

c3  g7 4 e4 d6 5

g7 4 e4 d6 5  e2 0-0 6

e2 0-0 6  g5 c5 7 d5 b5 8 cxb5 a6.

g5 c5 7 d5 b5 8 cxb5 a6.

White to play

This occurred in a 1967 game from the first issue of the Chess Informant – and 7 … b5 was given a question mark without comment.

White replied 9 a4 and had little trouble making his extra pawn count after 9 …  a5 10

a5 10  d2 axb5 11

d2 axb5 11  xb5

xb5  a6 12

a6 12  ge2

ge2  bd7 13 0-0 and then 13 …

bd7 13 0-0 and then 13 …  xb5 14

xb5 14  xb5

xb5  b6 15

b6 15  c2

c2  fc8 16

fc8 16  c3.

c3.

But 7 … b5 wasn’t bad. Like many sacrifices, it required a vigorous follow-up, such as 10 …  b4 11 f3

b4 11 f3  fd7 12

fd7 12  c1 c4 with …

c1 c4 with …  c5-b3 in mind.

c5-b3 in mind.

There are two basic forms of this sacrifice and in both cases the aim is to acquire two or three passed queenside pawns in return for a piece.

One form arises in the Sicilian Defense when Black plays … a6 and … b5 and has a pawn at d6 that is not protected by an e-pawn.

Adams – Pelaez

Innsbruck 1987

White to play

Typical moves in this kind of position are 1 g5, 1  d3 and 1 a3. But here White has an extra option, a capture on b5. After he retakes

d3 and 1 a3. But here White has an extra option, a capture on b5. After he retakes  xb5 he attacks the queen and earns a third passed pawn as compensation.

xb5 he attacks the queen and earns a third passed pawn as compensation.

White can sacrifice a bishop or knight on b5. He chose 1  dxb5! and play went 1 … axb5 2

dxb5! and play went 1 … axb5 2  xb5

xb5  c6 3

c6 3  xd6+

xd6+  xd6 4

xd6 4  xd6

xd6  xd6 5

xd6 5  xd6.

xd6.

Now we can see that 1  xb5+ would have been the wrong way to start because without a bishop on the board White would allow 5 …

xb5+ would have been the wrong way to start because without a bishop on the board White would allow 5 …  c4!.

c4!.

Black to play

White’s passed pawns aren’t as important as his edge in development. That was enhanced by the trade of queens and grew after 5 …  bd7 6 g5!

bd7 6 g5!  e7 7

e7 7  d2

d2  e8 8

e8 8  e2

e2  c7 9

c7 9  hd1.

hd1.

Black can hardly move a piece (9 …  b6? 10

b6? 10  c5+ and mates; 9 …

c5+ and mates; 9 …  b7 10

b7 10  xd7+; 9 …

xd7+; 9 …  b5 10

b5 10  d3 and 11

d3 and 11  b3 or 11 c4).

b3 or 11 c4).

Play went 9 …  d8 10

d8 10  a7

a7  b7 11

b7 11  c5+

c5+  e8 12 a4 and then 12 … f6 13 gxf6 gxf6 14 f4!

e8 12 a4 and then 12 … f6 13 gxf6 gxf6 14 f4!  f7 15

f7 15  h5+

h5+  g7 16

g7 16  e7 resigns (16 …

e7 resigns (16 …  g8 17

g8 17  xd7).

xd7).

The less common, but typically more dangerous, form of this sacrifice arises when queenside pawns are fixed: White pawns at b4, c5 and d4 facing Black ones at b5, c6 and d5.

Bronstein – Botvinnik

World Championship 1951

White to play

White knew the pattern and had been thinking about a sacrifice for five moves. “Two passed pawns, advancing on enemy pieces, have brought me more than a dozen points in tournaments of various ranks,” he wrote of 1  xb5!.

xb5!.

The pawns’ advance will be aided by the knight when it reaches d6. Black inserted 1 …  xe5 2 fxe5

xe5 2 fxe5  h6 3

h6 3  c1, then 3 … cxb5 4

c1, then 3 … cxb5 4  xb5.

xb5.

White pawns do a good job of taking squares away from Black pieces, so he stayed in the middlegame with: 4 …  d7 5

d7 5  d6

d6  xa1 6

xa1 6  xa1

xa1  a8 7

a8 7  c3.

c3.

There was no way to stop b4-b5 and the game went 7 …  f8 8 b5.

f8 8 b5.

Black to play

Black’s best defense in such positions lies in blockading the pawns or giving up a piece for two of them, 8 …  b8 9 c6?!

b8 9 c6?!  xc6.

xc6.

Something similar could have arisen when the game went 8 …  xd6 9 exd6

xd6 9 exd6  a4. Then 10 c6

a4. Then 10 c6  xb5 11 cxb7

xb5 11 cxb7  xb7 12

xb7 12  c7 and 12 …

c7 and 12 …  xc7 13 dxc7

xc7 13 dxc7  b6 would have held. In the end the game was drawn.

b6 would have held. In the end the game was drawn.

One of the most unlikely of sacrifices arises in positions like this:

White to play

Black’s pieces don’t easily defend the kingside so 1  d3 followed by 2

d3 followed by 2  c2 used to be common. After Black defended with … g6, White shifted his queen,

c2 used to be common. After Black defended with … g6, White shifted his queen,  d2-h6, and looked for a way to play

d2-h6, and looked for a way to play  g5 and/or h2-h4.

g5 and/or h2-h4.

But GM Yuri Razuvaev proposed an immediate 1 h4! to save time and support  g5. His main line ran 1 …

g5. His main line ran 1 …  xh4 2

xh4 2  xh4

xh4  xh4 and now 3

xh4 and now 3  f3.

f3.

By attacking the knight at c6 White wins time for  e4. Analysis has found that 3 …

e4. Analysis has found that 3 …  b7 4

b7 4  e4

e4  d8 5

d8 5  h5 is best.

h5 is best.

Then 5 …  a5 6

a5 6  h4

h4  xh4! 7

xh4! 7  xh4

xh4  xc4 is a sound queen sacrifice and 6

xc4 is a sound queen sacrifice and 6  g4!

g4!  xc4 7

xc4 7  h6 g6 8

h6 g6 8  h4

h4  xh4 is nearly as good. That’s one of several versions of the h2-h4 gambit that arise in this pawn structure. In practice the gambit is declined more often than it’s accepted.

xh4 is nearly as good. That’s one of several versions of the h2-h4 gambit that arise in this pawn structure. In practice the gambit is declined more often than it’s accepted.

Sanguineti – Averbakh

Portoroz 1958

Black to play

White has just played 1 h4. Accepting the pawn, 1 …  xh4 2

xh4 2  xh4

xh4  xh4, is dangerous after 3

xh4, is dangerous after 3  g5!.

g5!.

This is shown by 3 …  g4 4 f3

g4 4 f3  h5 5

h5 5  f2! followed by

f2! followed by  h1. Or 4 …

h1. Or 4 …  g3 5

g3 5  f6, threatening

f6, threatening  h6 and mate on g7.

h6 and mate on g7.

Black just ignored the h-pawn and met 1 h4 with 1 …  d6!. This stops White from transferring his queen to f4 and g4, followed by

d6!. This stops White from transferring his queen to f4 and g4, followed by  g5/h4-h5.

g5/h4-h5.

White could still try to make kingside threats with 2 h5 and then 2 …  a5 3 hxg6 hxg6 4

a5 3 hxg6 hxg6 4  e5 followed by

e5 followed by  f4.

f4.

But he stumbled with 2  g5

g5  a5 3 f3?. Black replied 3 …

a5 3 f3?. Black replied 3 …  g3! 4 h5

g3! 4 h5  d6 and won after 5 hxg6

d6 and won after 5 hxg6  h2+ 6

h2+ 6  f1 hxg6 7

f1 hxg6 7  e4

e4  xe4 8 fxe4

xe4 8 fxe4  g3! 9

g3! 9  e3

e3  c4.

c4.

f5 Hop

f5 HopWe examined the knight shift to f5 as a priyome. When the shift is discouraged by … g6, White can insist on it.

Byvshev – Geller

Kiev 1954

White to play

White had been preparing 1  f5!? gxf5 2 gxf5 in the previous dozen moves. He analyzed 2 …

f5!? gxf5 2 gxf5 in the previous dozen moves. He analyzed 2 …  f8 3 h5, when the threat of 4 h6 would prompt 3 … h6 4

f8 3 h5, when the threat of 4 h6 would prompt 3 … h6 4  xh6

xh6  xh6 5

xh6 5  xh6 and 5 …

xh6 and 5 …  e8.

e8.

Then 6  xf6 would allow Black to defend with 6 …

xf6 would allow Black to defend with 6 …  xh5 (7

xh5 (7  h6

h6  xf3). But White has other options, including 6

xf3). But White has other options, including 6  g6 or 6

g6 or 6  h2.

h2.

But Black didn’t try to refute 1  f5. He just replied 1 …

f5. He just replied 1 …  f8 and turned his attention to the queenside. White needed a new idea and he passed up the best one, 2

f8 and turned his attention to the queenside. White needed a new idea and he passed up the best one, 2  eg3 followed by 3

eg3 followed by 3  h5!.

h5!.

Instead, he played 2  h6+?

h6+?  xh6 3

xh6 3  xh6 and his attack was stalled, since h4-h5 will be met by … g5!, sealing the kingside.

xh6 and his attack was stalled, since h4-h5 will be met by … g5!, sealing the kingside.

This enabled Black to open the other wing after 3 …  ab8 4

ab8 4  c1 a4. He had the edge after 5 cxb4

c1 a4. He had the edge after 5 cxb4  xb4 6

xb4 6  c3 and won well after 6 …

c3 and won well after 6 …  b7 7

b7 7  c2

c2  xb2 8

xb2 8  xa4

xa4  xg2 9

xg2 9  xg2

xg2  e7 10

e7 10  xd7

xd7  xd7 11

xd7 11  b2

b2  xb2 12

xb2 12  xb2 f5!.

xb2 f5!.

The idea of trying to open the g-file with  f5 also appears in Sicilian Defenses and positions with a fianchettoed Black bishop, as in this from a King’s Indian Defense.

f5 also appears in Sicilian Defenses and positions with a fianchettoed Black bishop, as in this from a King’s Indian Defense.

Spassky – Fischer

Sveti Stefan 1992

White to play

White has managed to open some kingside lines. But it won’t matter unless he gets his queen into play there. He would be worse after 1  xb4 axb4, for example, since the e4-pawn is falling.

xb4 axb4, for example, since the e4-pawn is falling.

In desperation, White tossed a piece, 1  f5? gxf5 2 gxf5. He dreamed of mates after

f5? gxf5 2 gxf5. He dreamed of mates after  g1 and

g1 and  d4. But Black safely took another pawn, 2 …

d4. But Black safely took another pawn, 2 …  xb2. His king is safe on h8 or h7 (3

xb2. His king is safe on h8 or h7 (3  g1+

g1+  h7 4

h7 4  d4?

d4?  xd4 5

xd4 5  xd4

xd4  c2+).

c2+).

White tried 3  f1 and resigned soon after 3 …

f1 and resigned soon after 3 …  d7 4

d7 4  b1

b1  xa1 5

xa1 5  g1+

g1+  h8 6

h8 6  xa1+ f6.

xa1+ f6.

In 1 d4 d5 games, the Catalan and similar openings, Black often grabs a pawn with … dxc4 and then protects it with … b5. It may look like White is gambiting his entire queenside.

White typically challenges b5 with a2-a4 and Black defends with … c6 and/or … a6. Then it’s a strong pawn mass or weak pawn mess, depending on what happens next.

In the simplest form, 1 d4 d5 2 c4 dxc4 3 e3 b5?! then 4 a4! is strong, e.g. 4 … a6 5 axb5 axb5?? 6  xa8 or 4 … c6 5 axb5 cxb5??

xa8 or 4 … c6 5 axb5 cxb5??

6  f3!. In more complex forms, tactics are more difficult to come by:

f3!. In more complex forms, tactics are more difficult to come by:

Alekhine – Bogolyubov

World Championship 1929

White to play

Black traded off his better bishop to make his d5-knight a tower of strength. His c-pawn denies White’s bishop its best diagonal: No  d3.

d3.

If White is going to justify his sacrifice, he must act quickly, with 1  g5!. He prepares 2

g5!. He prepares 2  h5 and, if 2 … g6, then 3

h5 and, if 2 … g6, then 3  h6

h6  e7 4

e7 4  xh7! and

xh7! and  g7.

g7.

Note that 1 … 0-0? fails to another thematic idea in such positions, 2  b1!. White threatens mate on h7 as well as 3 axb5. If Black gives back the pawn he has nothing to offset his weak squares and bad bishop.

b1!. White threatens mate on h7 as well as 3 axb5. If Black gives back the pawn he has nothing to offset his weak squares and bad bishop.

The game went 1 … f6 2 exf6  xf6? and White had a clear edge after 3

xf6? and White had a clear edge after 3  e2 a6 4

e2 a6 4  f3! (4 …

f3! (4 …  d5 5

d5 5  c2 g6 6

c2 g6 6  xh7! or 4 … h6 5

xh7! or 4 … h6 5  h5+).

h5+).

To play this kind of position, Black must take risks. Here that means 2 … gxf6! 3  h5+

h5+  d7 followed by …

d7 followed by …  e8, when White’s edge is minimal.

e8, when White’s edge is minimal.

When the pawn structure is fluid, White usually wants to change it:

Khalifman – Sveshnikov

Elista 1996

White to play

To safeguard his pawns, Black delayed development in favor of the bishop and queen moves. A natural plan for White is to prepare d4-d5, such as with 1 e4 a6 2  c3.

c3.

But he can play more forcefully with 1 b3!? and 1 … cxb3 2  xb3. For example, 2 … a6 3

xb3. For example, 2 … a6 3  d1

d1  e7 4

e7 4  a3!

a3!  xa3 5

xa3 5  xa3 with good play after

xa3 with good play after  ab1 and

ab1 and  ac4. Or 2 …

ac4. Or 2 …  xd4 3

xd4 3  b2 and 3 …

b2 and 3 …  b4 4

b4 4  xb4

xb4  xb4 5 axb5.

xb4 5 axb5.

Black chose to develop, 2 …  bd7. But 3

bd7. But 3  e3! created a threat of 4 d5!. Black’s queenside would be collapsing after 3 …

e3! created a threat of 4 d5!. Black’s queenside would be collapsing after 3 …  d5 4

d5 4  xd7

xd7  xd7 5

xd7 5  c3.

c3.

Instead, Black opted for 3 … c5 and then 4  xd7

xd7  xd7.

xd7.

White to play

He offered to give back the pawn (5  xb7

xb7  xb7 6

xb7 6  xb5).

xb5).

But White steered a more ambitious course with 5 d5 and his initiative eventually prevailed after 5 … bxa4 6  xa4 exd5 7

xa4 exd5 7  c3! d4 8

c3! d4 8  d5.

d5.

Black would also be in trouble after 5 … exd5 6  xd5

xd5  xd5 7

xd5 7  xd5

xd5  d8 8 axb5 or 5 … b4 6 dxe6 fxe6 7 a5

d8 8 axb5 or 5 … b4 6 dxe6 fxe6 7 a5  a6 8

a6 8  xb7 and

xb7 and  xe6+.

xe6+.

We saw in Chapter One how h2-h4-h5 is a priyome to challenge … g6. If Black guards h5 with …  f6, the pawn push is a super-sharp sacrifice.

f6, the pawn push is a super-sharp sacrifice.

White to play

When this Sicilian Dragon position first appeared White tried standard attacking ideas such as g2-g4 to support h4-h5, and  h6. But 1 g4 is slow. And 1

h6. But 1 g4 is slow. And 1  h6?

h6?  xh6 2

xh6 2  xh6 allows 2 …

xh6 allows 2 …  xc3! 3 bxc3

xc3! 3 bxc3  a5, an excellent version of the …

a5, an excellent version of the …  xc3 sacrifice.

xc3 sacrifice.

Then 1 h5! was found to be sound in view of 1 …  xh5 2 0-0-0. White has a juicy target at h7 after 2 …

xh5 2 0-0-0. White has a juicy target at h7 after 2 …  c4 3

c4 3  xc4

xc4  xc4 4 g4, for example, and a winning plan of

xc4 4 g4, for example, and a winning plan of  h6xg7 followed by

h6xg7 followed by  h6+ and g4-g5.

h6+ and g4-g5.

His attack is so quick after 4 …  f6 5

f6 5  h6 that Black might consider the 5 …

h6 that Black might consider the 5 …  h8!? 6

h8!? 6  xf8 sacrifice that we will look at in a few pages.

xf8 sacrifice that we will look at in a few pages.

There are several versions of the h4-h5 sacrifice. It can lead to heavier sacrifices, as in 1 d5 f5 2 g3 g6 3 h4  f6 4 h5!?

f6 4 h5!?  xh5 5

xh5 5  xh5! gxh5 when 6 e4 threatens

xh5! gxh5 when 6 e4 threatens  xh5 mate and gives White a strong attack.

xh5 mate and gives White a strong attack.

Another version is:

Shishkin – Borisenko

Rostov 1958

White to play

Black avoided … 0-0 because of h4-h5!, when …  xh5 might lead to a sound

xh5 might lead to a sound  xh5 sacrifice. Instead, he intends …

xh5 sacrifice. Instead, he intends …  b7 and … 0-0-0.

b7 and … 0-0-0.

But 1 h5!  xh5 2 g4 turned out to be good, since Black’s knight is exiled offside following 2 …

xh5 2 g4 turned out to be good, since Black’s knight is exiled offside following 2 …  hf6 3 g5

hf6 3 g5  h5.

h5.

That mattered after 4  e4! and 4 …

e4! and 4 …  b7 5

b7 5  a4 put c6 under fire. Black didn’t like 5 …

a4 put c6 under fire. Black didn’t like 5 …  c8 6

c8 6  xa7

xa7  a8 or 5 …

a8 or 5 …  b8 6 d5

b8 6 d5  d7 7 dxc6

d7 7 dxc6  xc6 8

xc6 8  b5!.

b5!.

In the end he complicated with 5 … b5 6 cxb6  b6 and lost after 7

b6 and lost after 7  b3 (7

b3 (7  a3! is better)

a3! is better)  c8 8 bxc6

c8 8 bxc6  xc6 9

xc6 9  xc6+.

xc6+.

f4

f4The King’s Indian Defense is a curious animal. Black plays …  g7 but often follows this by blocking the bishop with a pawn at e5.

g7 but often follows this by blocking the bishop with a pawn at e5.

One method of freeing the bishop is to maneuver a knight to f4, even when White has two pieces attacking that square. At the cost of a pawn, Black gets to play … exf4!.

Kamsky – Kasparov

Manila 1992

Black to play

White met Black’s last move, …  h5, with g2-g4. He underestimated 1 …

h5, with g2-g4. He underestimated 1 …  f4!. After 2

f4!. After 2  xf4? exf4 3

xf4? exf4 3  xf4 b5 Black would be strong on the dark squares, with …

xf4 b5 Black would be strong on the dark squares, with …  b6 and …

b6 and …  d7-e5 coming up.

d7-e5 coming up.

White acknowledged his error with 2  c2. Black left the gambit on the table with 2 … b5 3

c2. Black left the gambit on the table with 2 … b5 3  f2

f2  d7 4

d7 4  ge2 b4 5

ge2 b4 5  a4 a5!.

a4 a5!.

Allowing White to win the pawn and keep his dark-squared bishop this way is better than 5 …  xe2? 6

xe2? 6  xe2, when Black’s initiative slows.

xe2, when Black’s initiative slows.

The game went 6  xf4 exf4 7

xf4 exf4 7  xf4

xf4  e5 and then 8 0-0-0

e5 and then 8 0-0-0  c4!.