Zora Neale Hurston’s father, the Rev. John Hurston. Zora and her siblings were awed by “his well-cut broadcloth, Stetson hats, hand-made alligator-skin shoes and walking stick,” she recalled. (Florida State Archives)

John Hurston in 1906 with Zora’s stepmother, the young Mattie Moge. (Courtesy of Robert E. Hemenway)

At age 21, Zora lived in Nashville, Tennessee, with her oldest brother, Hezekiah Robert (Bob), while he finished his studies at Meharry Medical College. She is pictured with Bob, his wife, Wilhemina, and their third child, newborn Hezekiah Robert, Jr. This is the earliest known photograph of Hurston, who moved with Bob and his family to Memphis after he finished medical school in 1913. (Courtesy of Winifred Hurston Clark)

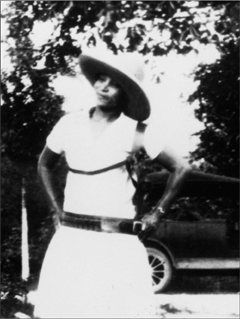

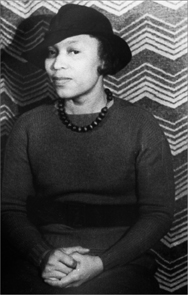

When the 26-year-old Hurston arrived in Baltimore in 1917, she still looked young enough to pass for 16, which she did—in order to qualify for free public schooling. “I got tired of trying to get the money to go,” she would recall. “My clothes were practically gone. Nickeling and dimering along was not getting me anywhere.” (ZNH Collection, University of Florida)

Hurston moved to Washington, D.C., in 1918 with hopes of attending Howard University. After working as a waitress all summer, she enrolled in the high school division, Howard Academy, in December. (ZNH Collection, University of Florida)

Hurston came into her own during her years at Howard, which she called “the capstone of Negro education in the world.” While attending classes full-time, she worked as a manicurist at a black-owned barbershop that served a white clientele. Averaging $12 to $15 a week in tips, she began to dress stylishly, favoring chic hats, long dresses, and dramatic colors. (ZNH Collection, University of Florida)

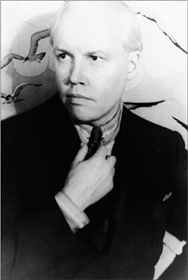

Alain Locke, pictured in 1926, was one of Hurston’s mentors at Howard and a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance. (Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Carl Van Vechten (left) and Fannie Hurst (above), both wealthy writers and well-known “friends of the Negro,” befriended Hurston shortly after her arrival in New York in 1925. (Photographs by Carl Van Vechten/Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection)

Hurston, shown displaying a variety of ethnic dolls, became interested in anthropology while studying with Franz Boas at Barnard College. Still, she felt certain that she wanted to be a writer. “I have had some small success as a writer and wish above all to succeed at it,” she wrote on an occupational interest form. “Either teaching or social work will be interesting but consolation prizes.” (ZNH Collection, University of Florida)

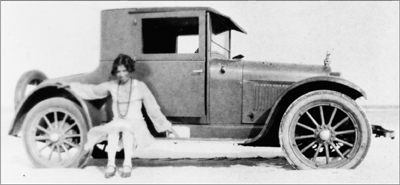

Carrying a pistol for protection, Hurston traveled through the South collecting folklore in 1927 in a car she called Sassy Susie. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Hurston ran into Langston Hughes during her tour of the South and they decided to travel back to New York together. The identities of the other men in the photo are unknown. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

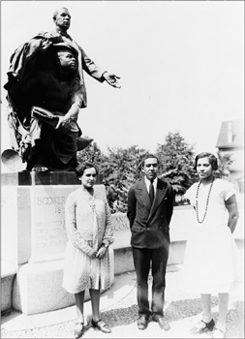

Jessie Fauset, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston in front of the statue of Booker T. Washington at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, 1927. (Photograph by P. H. Polk/Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

In May 1927, Hurston married her Howard University sweetheart, Herbert A. Sheen, who was then a medical student in Chicago. “He could stomp a piano out of this world, sing a fair baritone and dance beautifully,” she said of him. Though they’d been dating for years, Zora was “assailed by doubts” on their wedding day. (Rush-Presbyterian–St. Luke’s Medical Archives)

Charlotte Osgood Mason—patron to Hurston, Hughes, and several other artists of the Harlem Renaissance—required everyone who benefited from her largesse to call her “Godmother.” (Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Hurston returned to the South in 1928 to collect Negro folklore for Charlotte Mason (above), who furnished her with a motion-picture camera and a shiny Chevrolet. (Dorothy West Collection, Boston University Library)

Langston Hughes and Louise Thompson en route to Russia in 1932, a year after their dispute with Hurston over the play Mule Bone. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Hurston (far right) rehearsing a group of performers for From Sun to Sun, a folk concert she presented under a variety of names in New York, Florida, and elsewhere. This photograph was originally published in the April 1932 issue of Theatre Arts magazine. (ZNH Collection, University of Florida)

Zora Neale Hurston as pictured in Nancy Cunard’s massive 1934 anthology, Negro, to which Zora contributed six essays and a transcribed sermon. (ZNH Collection, University of Florida)

A portrait of the writer, photographed in Chicago by Carl Van Vechten, 1934. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection)

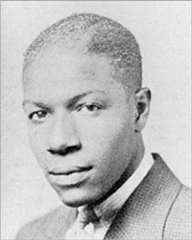

Percival Punter, the man with whom Hurston had what she called “the real love affair of my life.” When they began dating, in 1935, Punter was 23 years old; Hurston was 44. (Reproduced from the 1934 yearbook of the City College of New York)

The woman pictured at left has often been misidentified as Zora Neale Hurston. Her identity is unknown, according to Alan Lomax—who snapped the photo during the summer of 1935, when he, Hurston, and Mary Elizabeth Barnicle traveled through the South collecting folk songs for the Library of Congress. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Lomax Collection)

At right is a 1935 photo of Hurston by painter and lithographer Prentiss Taylor. Note that Hurston’s grin is not as toothy as her doppelganger’s, her eyes do not disappear into her smile, and she appears to be of a stockier build. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Hurston, at home in New York, demonstrating the Crow Dance. (Photographs by Prentiss Taylor/Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Detail of a page from Hurston’s manuscript of Their Eyes Were Watching God, which she wrote in Haiti in 1936. (Hurston Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Hurston has some fun with a drum she brought back from her 1936–37 trip to Haiti. The photo above was published in Voodoo Gods: An Enquiry into Native Myths and Magic in Jamaica and Haiti, the U.K. version of Tell My Horse. (New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection, Library of Congress)

At the New York Book Fair in November 1937, shortly after Their Eyes Were Watching God was published. A newspaper photographer snapped Hurston inspecting American Stuff, an anthology that included two of her most persistent critics, Sterling Brown and Richard Wright. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, WPA Collection)

Hurston (fourth from right) onstage in Jacksonville, Florida, at a 1938 performance inspired by Their Eyes Were Watching God. (Courtesy of the Skip Mason Archives)

At a football game in Durham in 1939, during her brief teaching stint at the North Carolina College for Negroes. (Photograph by Alex M. Rivera, Rivera Pictures)

On a folklore-collecting trip in 1940, on the coast of South Carolina. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Margaret Mead Collection)

Portrait of the author in the 1940s. (Courtesy of the Archives of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution)

In 1943, Hurston received a Howard University Alumni Award for “distinguished service” in literature. Also honored at the charter day ceremonies were Dr. Orville L. Ballard (left) and Lt. Col. Campbell C. Johnson. (Reprinted from the March 3, 1943, issue of the Washington Evening Star)

In 1948, shortly before the publication of Seraph on the Suwanee. (ZNH Collection, University of Florida)

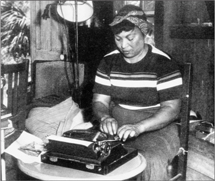

In 1951, Hurston returned to Eau Gallie, Florida, where, for $5 a week, she rented the same one-room house where she’d written Mules and Men. (Courtesy of The Saturday Evening Post)

At age 65, Hurston was a special podium guest at the 1956 commencement exercises at Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach, Florida. Two weeks later, she began a job as a librarian for $1.88 an hour. She spent her final years laboring on a book about the life of King Herod. She was working, she said, “under the spell of a great obsession.” (ZNH Collection, University of Florida)