Chapter 4

The Performance of Me

WHEN GUESTS CAME to dinner at 103 Irving Street in Cambridge, they spent the whole evening in the kitchen. The table was big and comfortable, and Julia liked having everyone around while she cooked: sometimes she invited people to pick up a knife or a whisk and join in. She would play culinary solos if necessary, but what she really enjoyed was chamber music—everyone on an instrument, chopping garlic or pouring wine or chatting, while a kind of Concerto for Food and Company rose up warm and fragrant in their midst. Cooking alone was very different, though in truth Julia was never really alone at the stove. Long before she cooked on television, she was aware of an audience—first her father and sister, impatient for breakfast as she frantically tossed pancakes and spilled coffee, and later the guests sitting politely in the living room, while she probed the beef with anguish and wondered if it was done, or overdone, or raw. As a bride, she practiced and practiced the role she called chef-hostess until she could give a dinner party without a glitch, or at least without any glitch she couldn’t smoothly mend, smiling and conversing all the while. “I always feel it is like putting on a performance, or like live TV or theater—it’s got to be right, as there can be no retakes,” she told Avis in 1953, nearly a decade before she saw a television camera for the first time. Testing recipes for the book, making the same dish over and over and over, she liked to pretend she was cooking in front of an audience. In part it was a form of culinary discipline, to keep herself from lapsing into casual, unprofessional methods; and in part she just enjoyed the company. When Julia did start cooking in front of a camera, her earliest fans constantly exclaimed over how “natural” she seemed on television, how “real,” how “honest,” how “homelike.” They were right. Performance had long ago become second nature to her.

Her first appearance on television came about shortly after the publication of Mastering the Art of French Cooking. She and Paul had decided some years earlier to live in Cambridge after his retirement, and they were still settling into their big clapboard house when Claiborne’s rave review appeared. “Presumably, with this puff, we are made!” she wrote jubilantly to Simca. “HOORAY.” Later that October, Simca arrived in the United States for the book tour, and the two women—suddenly newsworthy—were invited to be on the Today show. Julia wasn’t particularly nervous, maybe because she had never heard of it. She and Paul didn’t own a television set. But when she learned that four million people would be watching, she knew she needed a plan. “The quickest and most dramatic thing to do in the 5 or 6 minutes allotted to us was to make omelettes,” she reported to her sister afterward. “They said they would provide a stove.” What they actually provided was a reluctant hot plate, too feeble to heat up properly. But she and Simca brought three dozen eggs to the studio and spent the hour before their time slot practicing. Five minutes before airtime, they started heating up the omelet pan, and by a miracle it was red-hot by the time they needed it. Julia went away very much impressed with the show—everyone was friendly and informal, but the mechanics of the operation were absolutely professional and perfectly timed. It was exactly what she would aim for in her own television shows.

The next TV invitation came along several months later, and this was the one that changed her life. A penciled note is the only thing that remains:

Beatrice Braude UN4-6400

WGBH-Chan. 2 CO2-0428

84 Mass Ave

opp MIT

home = 354 Marlborough St.

TV

Beatrice Braude was an old friend of the Childs’ who had been fired from the USIS in Paris during a McCarthy purge. Now she was working in Boston at WGBH-TV, the fledgling public television station, where she arranged for Julia to be a guest on I’ve Been Reading, a book review program. “They wanted something demonstrated and had a hot plate!” Julia reported to Simca afterward. This time she had a full half hour, so she not only made an omelet, but gave a short lesson in beating egg whites and showed how to cut up vegetables and flute mushrooms. As far as she knew, the only people who saw the program were five of her friends and Jack Savenor, her Cambridge butcher. But twenty-seven ecstatic strangers wrote in to say they loved that woman who did the cooking, and begged the station to bring her back. At WGBH, twenty-seven letters was an avalanche. Startled and impressed, station executives asked Julia to work up a proposal for an entire series on French cooking.

It’s possible that Mastering, and with it Julia, would have drifted into relative obscurity if she hadn’t been discovered by WGBH. She certainly wasn’t about to be discovered by anyone else. Even the other stations in what was called educational TV would have been unlikely to take a chance on a plain-faced, middle-aged woman who did difficult cooking with a lot of foreign words in it. But WGBH was in Boston, and that made all the difference. Dozens of colleges and universities, long-standing Brahmin institutions such as the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the Museum of Fine Arts, and an unusually well-educated, well-traveled population made the area unique in the nation. The founders of WGBH intended the new station to be yet another jewel in the city’s cultural crown. French cooking fit right in; and, as viewers quickly made clear, so did Julia.

During the summer of 1962, she taped three pilot programs—omelets, coq au vin, and soufflés—and watched them at home on their new TV. She was horrified to see herself on-screen for the first time, swooping and gasping—“Mrs. Steam Engine,” she called herself—but she was determined to master the medium. “The cooking part went OK, but it was the performance of me, as talker and mover, that was not professional,” she told Simca. Everything had to be done more slowly, she decided, as if she were under water.

Those pilot programs have been lost, but judging from the letters that poured in to the station, the Julia who ventured in front of the camera that summer had already tapped an instinct for television. “I loved the way she projected over the camera directly to me, the watcher,” wrote one of these original fans. “Loved watching her catch the frying pan as it almost went off the counter; loved her looking for the cover of the casserole. It was fascinating to watch her hand motions, which were so firm and sure with the food.” Years later, when a friend mentioned that she was about to cook on television for the first time and felt nervous, Julia’s advice was simple: “Think about the food.” Whether she was flipping an omelet on a hot plate or holding up an unwieldy length of tripe in a beautifully equipped TV kitchen, food was the spark that ignited her performing personality and set it free.

Taping for the series began in January 1963. For her official debut as the “French Chef,” Julia chose boeuf bourguignon—a hallmark dish, resonant in her own memory and familiar to anyone who had ever been to a French restaurant. Besides, it was just beef stew. Surely even a housewife couldn’t be intimidated by that. And it would illustrate wonderfully well her favorite teaching topic: how French cooking was simply a matter of theme and variations. As soon as home cooks learned to brown beef, deglaze the pan, and set the meat to simmering in wine, they could do the same with lamb, veal, or chicken. Back in the nineteenth century, Julia’s long-ago colleagues in domestic science had been equally entranced by the marvelous logic of culinary structure, and were inspired just as she was to make it the basis of their gospel. Of course, they were teaching variations on white sauce, not variations on French stew; but Julia’s radiant faith in the message was kin to theirs.

Julia practiced hard: she wrote and rewrote the script, cooked and recooked the stew, figured out the timing for each step of the recipe, plotted her way around the TV kitchen, and tried to memorize the first few sentences she would say. Once the cameras started rolling, they wouldn’t stop—the budget didn’t allow for breaks and splices—so the show had to be choreographed as tightly as a high-wire act. On Monday evening, February 11, at 8:00 p.m., a large covered casserole appeared on black-and-white television screens across New England, and a breathy voice exclaimed triumphantly, “Boeuf bourguignon! French beef stew in red wine!” A hand lifted the lid from the casserole. “We’re going to serve it with braised onions, mushrooms, and wine-dark sauce,” the voice went on, lingering fondly over each word in wine-dark sauce, while the hand moved a spoon gently through the stew. “A perfectly delicious dish.” Then the voice dropped to a mumble—“I’m gonna…”—and abruptly stopped. The camera followed the spoon as it emerged from the stew and traveled higher and higher until it reached a mouth. Now a woman’s face appeared on-screen, eyes lowered as she leaned intently over the casserole and tasted. Then she straightened up with a satisfied expression, covered the cassserole and put it in the oven, and set a platter of raw meat on the counter. She looked pleasantly into the wrong camera, looked pleasantly into the right camera, closed her eyes for a second, and said, “Hello. I’m Julia Child.”

Despite the easygoing warmth that came naturally to her, this debut never quite shook off an air of nervous tension. Julia had no gift for artifice: she could perform, but she couldn’t pretend, and not until she turned to the platter of raw beef did she palpably relax. The sight of raw ingredients always restored her equilibrium. “This is called the chuck tender, and it comes from the shoulder blade, up here,” she explained, indicating the location on her own body. Apparently the director hadn’t expected such a graphic show-and-tell, because the camera remained fixed on the beef. “And this is called the undercut of the chuck, and it’s like the continuation of the ribs along here, where it gets up to your neck.” Finally, the camera reached her, just in time to see Julia running her hand up her own side. She cut the meat into chunks, chatting comfortably about quantities per person and handling the meat as affectionately as if she were powdering a baby. Then came the browning of the beef, three or four minutes that strikingly illustrated how television—at least as Julia conceived it—could be a great teacher of cooking. Browning is a simple procedure, but there are many more ways to do it wrong than right; and mistakes can ruin the meat. In her methodical way, Julia discussed the pitfalls and how to avoid them, browning the meat properly while an overhead mirror made the contents of the pan clearly visible. To a novice cook, or an experienced cook with bad habits, this lesson would have been life-changing.

After deglazing the pan with wine, she poured the wine over the meat—“just enough liquid so that the meat is barely covered,” she instructed, and added tenderly, “It’s called a fleur in France. When the meat looks like little flowers.” Julia had long ago acquired a correct if unmusical French accent, but here she deliberately lapsed into the vulgate. “A fleur” became “ah flerr” and “beurre manie” came out “burr man-yay,” both pronounced in careful Americanese. Perhaps she was trying to sound unpretentious, but she needn’t have worried; she was incapable of sounding anything else. In later programs her accent returned to normal.

Here, right at the start of her long career on television, Julia was already recognizably Julia—straightforward, intelligent, relishing the work, and giving star treatment to the food. Her all-important butter dish, the size and shape of a small rowboat, was at the ready; and though she praised her nonstick pan, she made it clear that a nonstick pan was no excuse for cutting back on the butter and oil. Standing at the dining table in the last moments of the show, a ticking clock all but visible in her eyes, she summed up what the program had covered—reminding viewers for at least the third time that they could do lamb, veal, and chicken exactly the same way—and invited them to return for French onion soup next week. She had composed a sign-off—“This is Julia Child, your French Chef. Bon appétit!”—but it disintegrated in the flurry of the final seconds. “This is Julia Child, welcome to The French Chef, and see you next time,” she said, rather confusingly. “Bon appétit!”

Throughout the WGBH broadcast area, audiences fell in love. “We have gotten quite a few calls, etc., and people seem to like it,” Julia told Koshland after “Boeuf Bourguignon” was aired. “It went quite well, I thought, though a bit rough and hurried in spots.” Nobody seemed to mind the rough spots. By March, some six hundred letters had poured in, many asking for the recipes, and others simply expressing rapture. “The station is getting a bit worried as it costs them about 10 cents an answer, but luckily quite a few of the letters enclose contributions to the station. I think we are luckily in at just the right time, as there have been no cooking shows for years, and people are evidently just ripe for them,” she wrote to Koshland. Julia often attributed her success to luck and good timing, but the onslaught of mail made it perfectly clear why people responded to The French Chef: it was Julia.

“We love her naturalness & lack of that T.V. manner, her quick but unhurried action, her own appreciation of what she is producing. By the time she gets to the table with her dish and takes off her apron, we are so much ‘with’ her that we feel as if someone had snatched our plates from in front of us when the program ends.”

“I love it where you say, ‘Oh, I forgot to tell you thus and so’ (so human and consoling to amateur cooks).”

“You are such a refreshing change from all the dainty cookery and gracious living that women are bombarded with—I hope you live to be a hundred and grow to enormous size.”

“Your honesty & forthrightness in all you do and say is greatly appreciated & welcomed in this age of phonyness & half-truths. We love you, Julia!”

“I love your T.V. program! You are the only person I have ever seen who takes a realistic approach to cooking.”

“Bernard Berenson wrote that there are two kinds of people, life-diminishing people and life-enhancing people. Certainly you must be the most life-enhancing person in America!”

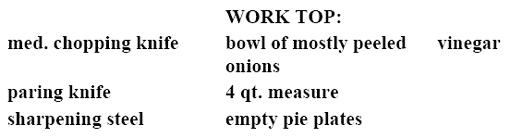

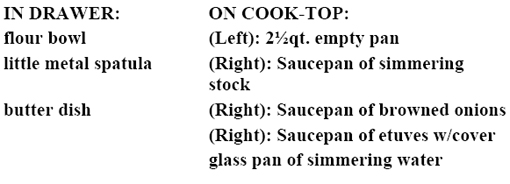

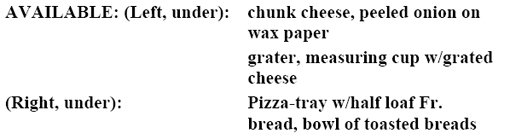

Julia once said that nineteen hours of preparation went into every half-hour show. First she broke down each recipe into segments, and then she did each step in her kitchen at home while Paul timed her with a stopwatch. How long did it take to chop a sample of onions for onion soup while describing how to hold and use a knife most efficiently, the way chefs did? How long did it take to start the onions cooking in butter and oil? To demonstrate browning the onions with sugar, salt, and flour? To blend stock into the onions and add wine? They worked on each step again and again, trying out different words and phrases, and different ways of showing a particular technique. Then they prepared a script, in the form of a detailed chart displaying time sequences, food, equipment, procedures, and what Julia would say. (Though she worked hard getting the wording as precise as possible, only the very beginning of the show was memorized; the rest she entrusted to adrenaline.) Every single item to be shown or mentioned—oven temperatures, pots of boiling water, samples of asparagus unpeeled and peeled and too scrawny to use, spice jars, spatulas—was listed on the chart in order of discussion. Julia did all the necessary precooking, including a fully prepared version of the dish as well as various ingredients in different stages of readiness. Paul meanwhile created diagrams showing the TV kitchen from Julia’s perspective as she faced the camera, with the location of every utensil and every morsel of food.

IN OVEN: Casserole of gratinéed soup

Conditions in the TV kitchen were primitive: WGBH had burned to the ground two years before, and the new building wasn’t finished yet. The first sixty-eight shows were staged in a donated display kitchen at the Cambridge Electric Company, where all the equipment had to be hauled in for rehearsals and taping, then hauled out again. On rehearsal day, Julia and Paul got up at 6:00 a.m. and packed their station wagon with precooked and partially cooked food, raw food, equipment and charts. They also tucked in any special items needed for a particular show, such as the thirty-square-inch chart of a beef carcass that Paul worked on one night until 2:00 a.m., drawing the bone structure and including all the classic cuts of beef. They discovered early on that it was easier to use the fire escape at the electric company than to load and unload the freight elevator, so the two of them carried everything up and set it out on long folding tables. Then Julia and the producer, Ruth Lockwood, rehearsed all day and into the evening, using what Julia called “live food” because that was the only way to get the timing and all the details correct. While they worked, Paul washed mountains of dishes. Then the Childs packed the car, went home, unpacked the car, Julia had a shot of bourbon and made dinner, and they went to bed.

On taping days, they did the same packing and hauling, and while Julia and Ruth were rehearsing, crew members began to arrive, lugging cameras and equipment up the fire escape. The studio became a mass of lights, cameras, and cables. The control center was in a trailer parked around the corner, where director Russ Morash sat watching two screens and issuing instructions to the cameramen. The crew worked out the lighting and camera angles, Julia was made up, and a microphone was hooked to the inside of her blouse, with a wire running down her left leg and into an electrical outlet. (By a miracle, she never tripped over this tether.) Finally, the floor manager shouted, “Sixty seconds! Quiet in the studio!” Julia looked into the camera, and taping began. Afterward, the crew devoured all the cooked food and took a break, while Paul washed dishes. Then the kitchen was set up with all different food and equipment, and a second show was taped. Bourbon and dinner followed.

The schedule was relentless, and despite the hours of rehearsal, those twenty-eight minutes were harrowing. One day the studio was so hot that after they completed the run-through, the butter was put into the refrigerator instead of being placed in the drawer where Julia was supposed to find it at the proper time. When the time came, she told Simca, “All I found was a little bowl with a paper in it saying ‘butter.’ So I had to say, ‘Merde alors, forgot the butter, always forget something,’ and go practically off camera to the frig. And I pull out the butter carton and find to my horror it has only about 30 grams of butter in it. Luckily I was able to spot when one camera was off me and focusing on the chicken, and was able to mouth an anguished ‘BUTTER’ to the floor manager, who snuck into the frig, with trembling fingers peeled paper off a piece of butter, and snuck it on the work table, with no camera spotting him.” The production team used to say they aged ten years with each show. But over the years, only a handful of shows had to be redone because of accidents or mistakes Julia couldn’t fix on the spot. The second show, on onion soup, was one she couldn’t save: she swept through the recipe so quickly that she arrived at the dining table with seven minutes to fill with chat instead of two. After that experience, they worked out a system of what they called “idiot cards”—nearly one a minute, tracking the time and reminding Julia what she was supposed to say and do. ASPARAGUS. SET TIMER. HOW BUY, STORE. FRONT BURNER HOT. (The camera she was supposed to be looking into some-times wore a small hat and a sign: ME FRIEND.) Later a second set of cards, orange instead of white, was introduced for emergencies. If Julia forgot an ingredient, or described a pot as “aluminum-covered steel” instead of “enamel-covered steel,” Ruth Lockwood would flash a special orange card alerting her to the error, and Julia would make the correction.

Six months into it, Julia was getting quite good, Paul reported to his brother. “Now she wipes the sweat off her face only when the close-up camera is concentrating briefly on the subsiding foam in the sauté-pan, for example. Her pacing is steady rather than rush-here and hold-there. She knows how to signal the Director that she’s going to make a move out of range of the cameras, so they can follow, by saying, ‘Now I’m going to go to the oven to check-up on the soufflé’—instead of suddenly darting out of the picture toward the oven.” WGBH continued to be overrun with letters from enchanted viewers. The Boston Globe published an editorial calling the show “the talk of New England” and signed up Julia as a regular columnist in the food pages. Kitchenware stores found they were running out of items Julia used on the show—flan rings one week, oval casseroles the next. “I can hardly go out of the house now without being accosted in the street,” Julia told Koshland in some amazement. New York, San Francisco, Sacramento, Philadelphia, Washington, and Pittsburgh all picked up the show, and floods of mail poured into every new station as soon as Julia appeared on-screen. Stories ran in Time, Newsweek, the Saturday Evening Post, and TV Guide. By January 1965, all ninety stations on the public television network were carrying The French Chef, and WGBH found it could raise money for the station every week by selling tickets to the taping sessions at $5 apiece. Paul greeted the audience before each session and asked them please not to laugh aloud during the show.

Julia spent most of the next forty years on television—new programs and repeats, public television and commercial TV, season-long series and one-time specials. She was a star, a host, a guest, a commentator, and a voice-over; once, to the delight of millions including herself, she was evoked by Dan Ackroyd on Saturday Night Live in a skit that became a classic. (Hacking away at a chicken, he fatally cut himself and collapsed, shrieking, “Save the liver!”) She grew old on camera: the energetic teacher who whipped up an entire beef Wellington in a half hour gave way over the years to an elderly woman who charmed the audience while letting guest chefs do most of the cooking. But her lasting image was established in the 1960s and 1970s by The French Chef. This was the Julia who won a permanent place in the nation’s memory bank.

The self-consciousness that fluttered through the “Boeuf Bourguignon” show quickly disappeared with experience, but Julia retained a real-world quality that television couldn’t tame. Even the food seemed to be a live, spontaneous participant. Julia welcomed it warmly and gave everything she had to the relationship—parrying with the food, letting it surprise and delight her, very nearly bantering with it. Sometimes she lifted a cleaver and made a fine show of whacking the food to pieces, as if they had both agreed beforehand that the end happily justified the means. The day she made bouillabaisse, she placed a massive fish head on the counter and kept it there by her side, one great bulging eye staring out at the camera, while she prepared the stock. Every now and then she found a reason to pick up the gigantic head and fondle it. Tasting, of course, was a recurring event in each program, each taste a cameo moment treasured by the camera. Julia’s whole countenance shut down as she lifted the spoon and focused inward, then she opened up again and, most often, looked pleased. “Mmm, that’s good.” And if there was a chance to nibble, she unabashedly nibbled. After a painstaking demonstration of how to fold the egg whites into the chocolate batter for a reine de Saba cake, she held up the spatula and announced, “We have this little bit on the edge of the spatula which is for the cook.” Avidly, she licked up the raw batter—a treat as old as cake baking—and added, “That’s part of the recipe.”

Julia never said cooking was easy, but she said many times that anybody could learn it who wanted to. Viewers following her through the steps of a recipe could see for themselves how the consistency of a batter changed as the eggs were added, could watch the chocolate melting safely over a pan of hot water, could read the confidence in her motions as she snipped the gills off a sunfish with shears, or plunged a lobster headfirst into boiling water. Nothing was left unsaid, very little was relegated to instinct. Often she tossed in salt or spices without using a measuring spoon, but she always knew the exact amounts and mentioned them. “Here’s what half a teaspoon of salt looks like,” she said once, and poured it into her hand to show people. She was teaching people to use their senses when they cooked, because she thought the senses belonged in every well-run kitchen, like good knives. There was no better instrument in the service of accuracy than an attentive cook who was watching and smelling and tasting. Monitoring the progress of a syrup for candied orange peel, she made a point of listening for the “boiling sound” coming from the mixture. You can use a thermometer here, she told viewers, “but I think it’s a good thing to see and feel how it is.”

Cooking shows had been a staple of early television, but none of them bore any resemblance to The French Chef. Most were plain-spun, local broadcasts featuring a home economist or food editor. James Beard and Dione Lucas, two of the best-known culinary authorities before Julia’s arrival on the scene, had starred in their own cooking programs, but neither of these experts was able to develop the skill or personality demanded by the screen. Their shows left no mark on the medium. By the 1960s, cooking had been relegated to the dim wastes of daytime TV, where it reveled in the simpleminded sentiments considered appropriate for housewives. Julia’s real peers were those beloved figures who made instant, indelible impressions in the first decades of television—Lucille Ball, Steve Allen, Milton Berle. Yet she stood out here, too, because what she was doing on-screen didn’t fit any existing categories. She invented no character, staged no formal entertainments; her original show didn’t even carry her name, and the point of the half hour over which she presided was to teach, not to focus attention on herself. In fact, Julia spent her first decade on TV begging WGBH to put guest chefs on The French Chef with her because she thought people would learn much more if they could be exposed to a wide range of teachers. (The station never complied, first because the program was so experimental, and later because it was so clearly and magnificently Julia’s show.) Despite the modesty that was intrinsic to her personality, the camera adored her, perhaps because she generally forgot about it as soon as the food absorbed her attention. Often she looked straight into the camera and gave a sudden little smile, because Ruth Lockwood had been holding up an idiot card that read SMILE. In a medium stoked by artificiality and blandness almost from the beginning, Julia was herself and famous for it.

At the same time, however, she tended her public image with great care. Paul did all the still photography for The French Chef and tried to make sure that his were the only photographs of Julia that appeared in the press. She was not conventionally good-looking or particularly photogenic, and newspaper photographers weren’t going to edit their contact sheets as painstakingly as he did. As he told his brother, “The image can be spoiled by letting out half a dozen stinkers.” Over the years, similarly, she went on many diets but rarely discussed them in public until late in her career. What she preferred to tell the press, when reporters invariably asked how she controlled her weight in the face of so much tempting food, was that she and Paul simply watched their calories and tried never to have second helpings. (But, “TOO FAT!” she groaned to an old friend. “I’m just too damned fat, my waist is middle aged, my bust is bulging bubbidom, and [worst of all], I really can’t buy any clothes anymore.”) A few years after she started on television, she bought her first wig—“which will save a pile of distress in rainy weather,” Paul explained—and in the late 1960s, she had plastic surgery for the first time, an “eye job.” In the spring of 1971, she had a complete face-lift. The operation took place in Paris so that she could go straight to their house in Provence to recuperate in absolute privacy. When she learned that Simca was planning to be next door in her house at the same time—Simca would be working with an American writer who was translating her cookbook into English—Julia insisted that the translating be done elsewhere or at another time. “You forget, ma chérie, that I am, malgré tout, a public figure and it will not do to have a reporter and writer be aware in any way of my condition,” she wrote to her colleague. “I am sorry to be difficult about this, but you must understand the problem!” Nobody knew about the face-lift—“my sacquepage,” Julia called it—except Paul, Simca, and Ruth Lockwood. “People think I look just fine, and so rested,” she wrote to Simca after returning home. “Avis said your skin looks so good, and your face—I said, well, since the TV I’ve learned how to put on makeup. Actually, it is very subtle—the neck fixed, the pouches at either side of the chin, and the hollows out of the cheeks. I didn’t realize myself until suddenly I looked—no turkey neck! No dewlaps!” She had plastic surgery again in 1977 and once more in 1989.

But her image was a bigger project than simply the condition of her face and figure. Soon after The French Chef became a local sensation, Julia began to get invitations—Would she appear at a department store and demonstrate cooking? Would she appear at a charity fund-raiser? Would she endorse this product, use this equipment on air, plug this restaurant? Early on, she made it a rule to say no to everything except charitable ventures. “I just don’t want to be in any way associated with commercialism (except for selling the book in a dignified way), and don’t want to get into the realm of being a piece of property trotting about hither and yon,” she told Koshland. “The line is sometimes difficult to see, but I know where I mean it to be.” Anytime she accepted a fee for a cooking demonstration or a special appearance, she donated the money to WGBH. If viewers wrote to ask where she bought her mixer, or what brand of rum she was using, she wrote back with the information, but she never mentioned a brand name in public. Thanks to the success of her books, as well as an inheritance, she and Paul didn’t need the money; and she often said how grateful she was to be able to turn down such offers. But she made her stance for another reason as well. Commercial endorsements were demeaning: they tarnished the reputation of the cook. James Beard lent his name to many food companies, always justifying it by saying he needed the money, and Julia felt that his standing in the profession was suffering as a result. Audiences understood the difference between paid-for and unfettered speech; they loved her for staying on the right side of the line, and she had no intention of letting them down by muddying what she called “the purest of noncommercial images.”

With the help of her lawyer when necessary, Julia kept her name free of commercial taint throughout her career. But other aspects of her public image had a way of tripping her up, often right on air. Scrupulous though she was about how she looked and how she taught, Julia was so comfortably at home whenever she was handling food that she moved around the TV kitchen as if she were in her own house. She stashed away the colander and then forgot where it was, hunted about for the mixing fork, lost track of a casserole; once she snatched up a huge handful of paper towels and swabbed her face, explaining, “I’ve got so many burners on here, I’m hot.” No matter how well she planned a program, moreover, reality had a way of breaking over the proceedings like a raw egg. Julia’s equanimity in the face of a crisis was dazzling—repairing the molded potatoes that stuck to the bottom of the pan, withstanding a series of electrical shocks from the microphone tucked in her blouse (she did keep fiddling anxiously with the mic, but she never stopped teaching), shoving aside a spoon holder that had fallen over with a crash, ignoring a scraper that flew from her grasp, and dismissing the collapse of a frosting-laden “twig” in the Yule log by remarking, “Well, I guess that would happen in a forest, anyway. Things sitting there a long time, and they begin losing their strength.” When she unmolded a tarte tatin, only to see it collapse into a messy heap of apples with the crust slipping off to the side, she simply said, “That was a little loose. But I’ll just have to show you that it’s not going to make too much of a difference, because it’s all going to fix up.” Rapidly she tucked the apples together on top of the crust, then carried the disheveled tart into the dining room along with another “ready” tart that had been unmolded perfectly earlier in the day. “Now everybody can get one of each tart,” she said as she cut slices, managing despite everything to sound like a chemistry teacher showing the results of an experiment that went off just as it was supposed to. “There. I think that actually makes a more interesting dessert.”

One day Julia taped a program with four different potato recipes, trying to move through them at a good pace. Standing at the stove over a large mashed potato cake in a skillet, she waited a little impatiently for the cake to brown on the bottom. She eyed the pan and shook it dubiously, then decided to try to flip the cake over anyway. Clearly she knew she was taking a chance. “When you flip anything, you just have to have the courage of your convictions, particularly if it’s sort of a loose mass, like this.” She gave the pan a swift, practiced jerk. The potato cake rose heavily into the air and disintegrated, half of it spilling in shreds onto the stove. “Well, that didn’t go very well,” she observed steadily. “You see, when I flipped it, I didn’t have the courage to do it the way I should have.” Quickly she gathered up the pieces and reassembled them in the pan. “You can always pick it up,” she remarked as she worked. “You’re alone in the kitchen—who is going to see? But the only way you learn how to flip things is just to flip them.”

“You’re alone in the kitchen—who is going to see?” This incident became legendary and then apocryphal, revised so many times in the telling that the original event disappeared. Julia dropped a chicken, Julia dropped two chickens, she dropped a turkey, a twenty-five-pound turkey, a pig, a duck, and in each case blithely returned them to their platters—all fantasies, but people recalled them joyfully. They also remembered seeing Julia pour wine into a dish, then finish off the bottle herself, saying, “One of the rewards of being a cook.” Actually, she had been showing how to juice tomatoes and finished the lesson by drinking up the last bit of juice; but memory preferred wine. “Sometimes she forgets to put the seasoning in the ragout; sometimes she drops a turkey in the sink,” wrote Lewis Lapham in the Saturday Evening Post. “In New York’s Greenwich Village…a coterie of avant-garde painters and musicians gathers each week in a loft to watch The French Chef, convinced that Mrs. Child is far more diverting than any professional comedian.” A story in Time played up her “muddleheaded nonchalance”; a piece in TV Guide reported “blunders,” “grunts,” and “mutters.” “Practically every article on Julie so far has concentrated on the clown instead of the woman, the cook, the expert or the revolutionary,” Paul complained to his brother. Julia hadn’t intended to do kitchen vaudeville, but that was the image taking shape—despite the fact that efficiency and competence characterized her television cooking far more accurately than pratfalls did.

Reading the fan mail as well as the press, Julia could see that the informality and humor that came so naturally were doing just what she wanted the show to do: dispel the fog of intimidation around French cooking. Hence she was willing to play up the entertainment aspect of the program, especially in the opening moments—sorting through mounds of tangled seaweed to reveal a twenty-pound lobster, for instance, or standing over a chorus line of six raw chickens exclaiming, “Julia Child presents the chicken sisters! Miss Broiler! Miss Fryer! Miss Roaster! Miss Caponette! Miss Stewer! And old Madame Hen!” But she was of two minds about the bloopers. They were peerless teaching tools: every cook ran into mishaps, and Julia knew that to see the pommes Anna stuck helplessly to the bottom of the pan, then rescued and restored, constituted a more memorable lesson than the original would have been. “It may well happen to you,” she always told viewers as she patched and revised. But she hated making mistakes in public. Informality was one thing; ruining the food was definitely another. And she didn’t want to be known as a bumbling clown; she wanted to be known as a good, professional cook. When hapless beginners wrote to her begging for advice—which they did in such numbers that she composed a form letter to send in response—she was full of sympathy and encouragement, but never admitted having been in the same position herself. “The story of the beginner cook is often a real tale of woe, and I feel for her,” she told them. “Whenever I sew or knit it turns out a disaster. I really think the best thing is to take some cooking lessons…. Cooks are made, geniuses are born, and you can learn to cook with the right instruction—especially if you are lucky enough to be married to someone who loves good food, as that will always inspire you.” It was, of course, her own story, minus the early agony.

“Bon courage!” she bid the audience at the end of the flopped-potato-cake show. Be of good courage! “Courage!” she said again, after a visibly exhausting bout with French bread. When she demonstrated the nerve-racking process of creating a lacy caramel “cage” to go over a cake, she didn’t try to disguise the challenge: she told viewers to fail if they must, and try again. “Cooking is one failure after another, and that’s how you finally learn,” she told the audience while she stirred the caramel. “You’ve got to have what the French call ‘je m’enfoutisme,’ or ‘I don’t care what happens—the sky can fall and omelets can go all over the stove, I’m going to learn.’” It was the chief lesson she had gleaned from her own cooking failures, which dogged her long after she had learned to cook. “I must say I find myself often in the embarrassing position of being the much publicized visiting supreme authority on culinary matters, and then laying an egg on top of it,” she wrote to Avis in 1953, after a Christmas visit to friends during which she botched the timing of a turkey. The next year she truffled and stuffed a turkey, then overcooked it, burned the broiled endive, nearly forgot the salad dressing, and was late with the coffee. “How miserable, depressing, and slapping-down such a fiasco is, is it not?” Nearly a decade later, living in Cambridge as the lionized author of Mastering the Art of French Cooking, she entertained her new friend James Beard and, she told Simca, “cooked the worst dinner of my life.” An elaborate preparation of veal scallops—cognac, Madeira, truffles—lacked flavor, and she didn’t know why; the broccoli was underdone, and so were the sautéed potatoes; and the chocolate cake tasted terrible. (“Don’t ever use Baker’s unsweetened chocolate for anything!”) Beard didn’t seem to mind the meal: he promptly invited her to teach at his school in New York.

Mistakes were bad enough at a dinner party for friends, but when she fumbled on television, the moment was captured forever on tape—and shown over and over in reruns. She knew audiences cherished the near disasters, but she longed for more control; she longed to present a more polished performance. “If we had more money, it would be so useful to overshoot and be able to edit out with dissolves to indicate time lapses—and no pretense that it is a live show,” she told Ruth Lockwood. The French Chef never progressed to that level, in part because the production team was determined to keep the show from becoming too slick, although with the advent of color and a new studio kitchen, the show looked far more dressed up by the time the last programs were taped in 1972. With the two series that followed—Julia Child & Company and Julia Child & More Company—Julia was able to move a good deal closer to the image she preferred. These programs, produced on a bigger budget with all the benefits of technology, were staged in a bright, chic kitchen without a trace of home to it: the sheen was pure television, and Julia herself seemed to revel in the artificiality. Perhaps because it was possible at last to do retakes, she was more relaxed and never looked as though she were lunging for her next words. Her relationship with the food remained as high spirited as ever—shaking a pan of cucumbers, slapping the dough on the counter, admiring the teeth on a gigantic monkfish, adding “homemade chicken stock, as you can see” as she poured it from a can. But if the tension that often marked The French Chef was gone, so, alas, was the gratifying sight of the unpredictable, leaping out of a bowl or skillet to test the mettle of the heroine.

For reasons nobody seemed able to explain, the Company series didn’t make much of an impact when they were first aired. WGBH admitted later that it had done a poor job of promoting and distributing More Company, which wasn’t seen at all in New York until it went into re runs. Julia had been a familiar presence on television for more than fifteen years and was considered a national treasure, but while critics and many of her fans were happy with the new shows—and the reruns went on forever—the initial ratings and publicity came nowhere near those of The French Chef. “I am quite aware that there comes a time when one is frankly out of style, out of step, and had better fold up and steal away,” Julia had acknowledged years earlier, as she foresaw The French Chef drawing to a close. “However, I shall certainly hang on with full vigor for the time being.” She was still vigorous, but the experience with Company persuaded her that if she wanted to keep going, she had to take her television career in a different direction. Like any artist, she was far more interested in the future than in settling back to read her old reviews. In 1980, she withdrew from the shelter of WGBH and began a long association with Good Morning America, her first regular commitment to commercial television. The two-and-a-half-minute cooking segments were enormously popular, and she relished the format for its efficiency, as well as for the huge new audience it delivered. By 1983, when shooting began on her next public television series, she had established her own production company, which meant she could exert much greater control over her own programs than she ever had before. She still thought of herself primarily as a teacher, but she was convinced that she had to package herself with far more glitz if her message was going to get out.

The idea for the new series, which she developed with director Russ Morash, was to offer not a cooking school show but a television magazine, glossy and expensive. Julia would do a bit of cooking, but she would also visit fisheries, farms, cheese makers, and vineyards, chat with guest chefs, and welcome guests to a luxurious party that would conclude each program. Home base for the show would be a twenty-five-acre ranch near Santa Barbara, and Julia would have hair, makeup, and wardrobe professionals outfitting her for each program. As a coproduction of WGBH and Julia’s own company, the new series would be, as her business manager put it, “quintessentially Julia’s own show.”

Dinner at Julia’s was a disaster, the only real embarrassment in her long career. Julia looked grotesque, her hair frizzed and her makeup garish, dressed up in caftans and evening pajamas, or rigged out for a barbecue in jeans, a vest, and a purple ten-gallon hat. Though she was never ill at ease, she had little of substance to do in her long stretches of time on camera. As she stood there listening to a winemaker or chocolatier describe how various products were made, she looked as if she were a cardboard replica of herself, deployed to lend the symbolic presence of Julia Child to an alien landscape. With the food, as always, she was restored to life, but the cooking sequences were designed to show only quick highlights from the preparation of a dish, not an entire recipe. Nothing that happened on-screen was alive or spontaneous; nature itself had been banished. Even the chanterelles in the mushroom-gathering sequence had been carefully tucked into the ground by hand, before the cameras arrived. The sumptuous mansion, the Rolls-Royce pulling up to the door, the staged parties with their make-believe guests pretending to have fun—it was a painful spectacle, and Julia’s fans were appalled. The reviews were lacerating, and the letters were worse. “To see this darling, feisty, gifted lady dressed up in cowboy clothes, tottering around in boots, swishing among rather wooden-looking ‘guests,’ and above all to see her modest, perfect little show given the Beverly Hills treatment, the ostentation, the waiters, the gratuitous free plugs for restaurants and grape-growers, cheese factories, and what not, well, it’s awful!” “I miss my old friend Julia.” “We want you to be human.” “How could you?”

Julia never apologized, any more than she did when she had to serve a soufflé fallen flat. “We had such a good time making those shows” was all she would say when a reporter asked her how she felt about the debacle. But it was another ten years before she returned to television with a new series, and this time she stayed on the sidelines. Cooking with Master Chefs featured sixteen chefs preparing meals in their home kitchens, and Julia—who called herself Alistaire Cookie and wished the series could be named Masterpiece Cooking—introduced each show. The only complaints about the program were that people wanted to see more of Julia. After that, she made sure to share the screen with her guests, acting as a personable interlocutor as they cooked; and the last three series she made—Cooking at Home with Master Chefs, Baking with Julia, and her duet with Jacques Pépin, Julia and Jacques: Cooking at Home—were all taped in the kitchen at 103 Irving Street. It was the right formula: old fans were satisfied, new ones were smitten, and Dinner at Julia’s faded from public memory.

Back in 1942, when Julia belonged to a team of volunteers who watched the skies over Southern California for enemy aircraft, a story in the local paper noted that members of the group habitually called each other “Mr.” or “Mrs.,” with one exception—“Julia McWilliams, whom everybody addresses as Julia.” Decades later, people were still addressing her as Julia. In person or on-screen, her whole countenance invited familiarity; barriers dropped away as if she had been a friend forever. Paul used to marvel at a phenomenon he witnessed again and again while they were living in Paris: he called it “la Julification des gens”—“the Julia-fication of everybody.” She had a way of hypnotizing people, he once said, “so they open up like flowers in the sun.” Nobody was insensible to her effect: one of the themes that ran through the piles and piles of mail was pure gratitude. “Thank you for being such a pleasure.” “Many thanks for bringing so much pleasure.” Or, as a thirteen-year-old put it, “I don’t know why, but whenever I see you it makes me feel good.” Hard as she worked on her image, in the end it was irrelevant. “You are so utterly real, I feel as if I know you,” a fan wrote. They did know her, perfectly.