{ two }

Time is God’s way of keeping everything from happening at once.

ANONYMOUS

THERE IS AN unseen dimension to the far-and-away spread of the prairies, and that dimension is time. At first glance, one might mistake this for a place that time and change have somehow overlooked. These level plains and soft, rolling hills seem to have settled here quietly, their surface unmarred by signs of geological strife. But appearances can be deceiving. The great grasslands of central North America have been shaped over the past three or four billion years by the same forces that raised the Rockies and excavated the Grand Canyon. Their surface has been seared by the sun, scoured by ice, blasted by blowing sand, and buried in deep drifts of gravel. As a result of immense energies beneath the surface of the Earth, the plains have been raised up, forced down, drowned by oceans, and blanketed in ash. They have experienced every shudder and wrench as continents have collided and torn away from each other, only to collide and tear away again.

The traces left on the surface of the prairies by this planetary bump and grind are surprisingly minimal. Yet if you know what to look for and where to look for it, the subtleties of the prairie landscape become eloquent. An oil well bears witness to ancient tropical seas. A vast level plain provides an unexpected reminder of the protracted violence of mountain building. A hummocky wheat field speaks of the lumbering passage of glaciers. To an observer with a little basic geological knowledge, even the most unspectacular prairie landscape suggests a long and spectacularly interesting history.

Under the Waves

Trilobite

To go back into the prairie’s history means to go down. The record and residue of times past lie beneath our feet, so wherever we go on the prairies, we are traveling across vanished worlds. Straight beneath you, for example, at a depth of between 2,000 and 4,000 miles (3,000 and 6,500 kilometers), lies the Earth’s core—the yolk of the planetary egg—which coalesced out of a whorl of star dust some 4.5 billion years ago. This partly solid, partly fluid center is encased in an equally ancient layer of rock called the mantle. And surrounding the mantle is a covering of waxlike malleable material known as the asthenosphere, which is kept at a lethargic boil by the heat of its own radioactive decay. As the source of the molten magma that periodically shoots up through volcanic fissures and rifts in the ocean floor, the asthenosphere is the main powerhouse of geological turmoil.

The roiling-and-toiling asthenosphere occupies a zone between about 45 and 150 miles (70 and 250 kilometers) below the surface. Between it and us lies a relatively thin and fragile shell of rock, known as the lithosphere. The outermost membrane of this rocky shell is the Earth’s crust, a layer that is thinner, proportionately speaking, than the skin of an apple. On the prairies, the crust extends to an average depth of 25 to 30 miles (40 to 45 kilometers). Yet this comparatively short vertical distance takes us back in time some 3.8 billion years, to an era when the flying debris of creation had begun to subside and the Earth’s crust was finally able to stabilize. In this remote and inhospitable age, we find the first traces of life—microscopic stains, a few microns long, made by filaments of cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae.

Rocks from this primordial era lie right out in the open on the Precambrian Shield, but they seldom break through to the surface of the Great Plains. Instead, these ancient formations generally lie a few miles beneath our feet, providing the foundation, or “basement rock,” on which the prairies have been built. Our region lies on what geologists call the North American craton, or the stable core of the continent. This is a large fragment of the Earth’s crust that sheared away from an unnamed supercontinent toward the end of the Precambrian Era. By the time this happened—some 600 million or 700 million years ago—the Earth (and the prairie region along with it) had already endured more than 3 billion years of mountain building, erosion, glaciation, deglaciation, and general geological Sturm und Drang. But things must have been starting to settle down, because when the supercontinent tore itself apart, it produced a North American continent-in-the-making that has persisted until the present.

The Earth has sometimes been likened to a layer cake, in which ancient sediments are overlain by deposits from successive geological events, creating an ascending timeline from past to present.

This infant continent was not exactly the land mass that we know today. The entire western Cordillera was missing, with the result that the west coast of the craton ran south through present-day British Columbia and the Pacific states (much closer to the prairies than it is today). At first, the cratonic land mass lay exposed—a low, eroding plain, as barren as the face of Mars. But, as the geological strife continued, sea levels began to rise and the land was gradually overrun by the ocean. In time, the entire continent (with the periodic exception of a chain of tropical islands that ran diagonally across the plains, from Lake Superior toward Arizona) had disappeared beneath the waves.

For roughly the next 55 million years (from about 545 million to 490 million years ago), much of the North American craton lay under a shallow sea. Wherever the land remained exposed, it was eroded by water and wind, which ground the gritty Precambrian rocks into rounded grains of quartz sand. This sand was then swept to the coasts and out into the sea, where it settled to the bottom in beds tens to thousands of yards thick. Eventually, these lustrous sediments were overlain by layers of fine-grained mud. And whether sandy or silty, this ocean floor was literally crawling with life, particularly three-lobed, many-legged, bottom-feeding arthropods known as trilobites. After an agonizingly slow start with the cyanobacteria, evolution was finally hitting its stride, producing a menagerie of weird and wonderful undersea life. As generation upon generation of these animals lived and died, their remains settled onto the ocean floor, where they were buried under thick layers of sediments. Today these fossil-rich deposits—now compressed into solid sandstone and shale—are buried some 3 miles (5 kilometers) beneath the wheat fields of the northern plains and at lesser depths in other parts of the prairies. But in a few places—like the Judith and Little Rocky mountains and the northern Black Hills—they have been pushed up to the surface, exposing their maritime history to plain view.

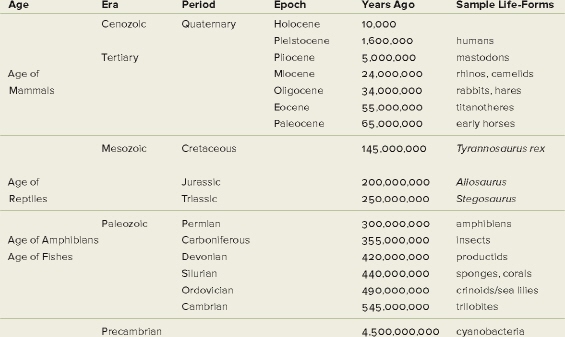

> GEOLOGICAL TIMESCALE

When the Cambrian sea finally withdrew and dry land emerged again, the forces of erosion immediately began to tear away at the newly formed rocks. But soon, geologically speaking—after a break of little more than 20 million years—the water rose and slowly spread over the land. This time, even the transcontinental island chain was bathed in the warm, clear seas. Now primitive snails munched on algae and were themselves preyed upon by giant squid-like nautiloids, with shells up to a couple of yards in length. Hundreds of new species of shelled animals evolved, including crinoids, or “sea lilies” (distantly related to modern sea urchins), and exotic reef-forming corals. There was so much life in these oceans that when they finally withdrew some 440 million years ago, they left behind thick deposits of shell fragments and calcium-rich debris, which eventually solidified into fossil-rich limestones. These Late Ordovician deposits include the elegant Tyndall stone that is quarried in Manitoba and graces so many buildings in the Prairie provinces.