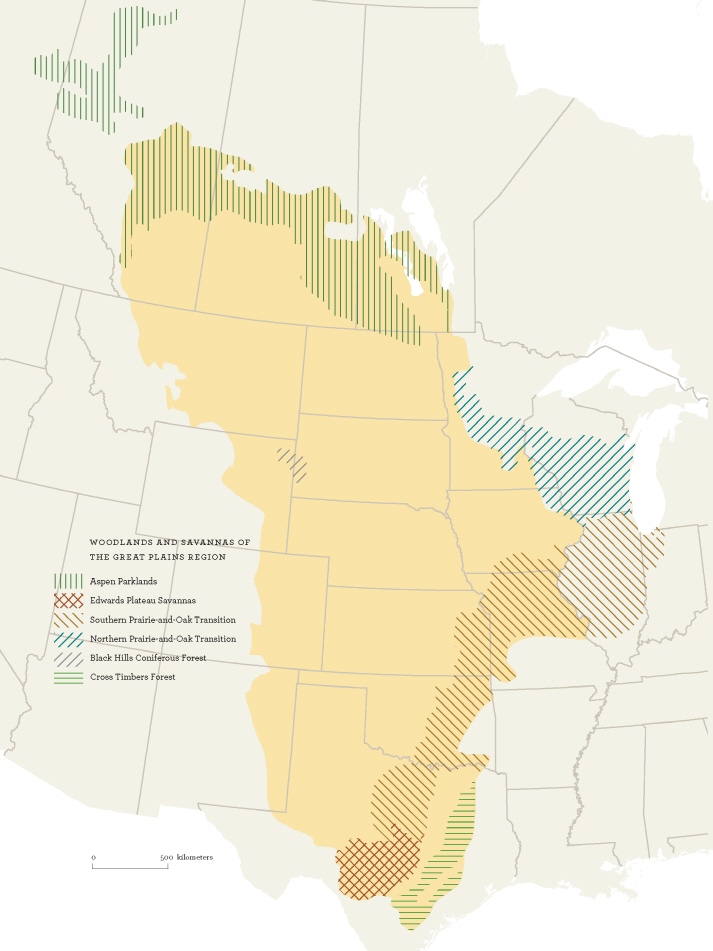

A comparable transition zone, or ecotone, is also found on the prairies’ northern shore, where mixed grasslands lap up against the boreal forest. Just as the west-to-east increase in precipitation encourages the growth of trees, so the south-to-north decline in average temperatures reduces the evaporative demand and creates conditions that are hospitable to forests. Somewhere around 52 degrees north latitude (about the latitude of Saskatoon), the climate strikes a balance between the requirements of certain midheight grasses— rough fescue, for example, and western porcupine grass—and those of various trees and shrubs, notably, trembling aspens. The result is a pleasantly varied landscape of rolling, grassy meadows and contoured groves, or bluffs, that is known as Aspen Parklands. Extending perhaps 60 miles (100 kilometers) from north to south, the parklands stretch all the way across the Prairie provinces, from the foothills of central Alberta to the Canadian shield, and south through Manitoba into northwestern Minnesota. There the broken stands of aspens shade imperceptibly into the savannas of hickory and oak that extend, with remarkably few interruptions, south to the Cross Timbers.

Thus, for the most part, prairie woodlands sort themselves along the gradient of the four cardinal directions, north, south, west, and east, in accordance with their ability to withstand water stress. On a finer scale, they tuck themselves into the prairies wherever the lay of the land either improves the supply of water to the roots or (through shelter and shade) reduces the evaporative demand on the foliage. That is why, for example, the north-facing slope of a coulee is often densely tangled with brush, while the exposed southern slope supports nothing but a carpet of forbs and grasses.

> OLD-GROWTH SPECIALISTS

For most of us, the phrase “old-growth forest” conjures up images of towering redwoods and massive firs in the misty gloom of the Pacific rain forest. We’re much less likely to think of scraggly old juniper or oak trees, out on the burning plains, that have taken four hundred years to reach the height of a two-storey building. Yet stunted and bent as they are, these venerable prairie warriors deserve not only the respect due to age but also consideration for their increasing rarity.

Take, for example, the twisted trees of the Texas Hill Country. Originally an open savanna of mixed woods interspersed with meadows of grass, the region was heavily logged in the late 1800s. Then, thanks to fire suppression, woody plants pushed back in, often in the form of dense, monotypic, pollen-spewing stands of the native “cedar,” or Ashe juniper. Despised by ranchers, developers, and allergy sufferers alike, Ashe juniper was soon listed as Public Enemy No. 1, to be attacked with all possible vengeance.

Yet Ashe juniper has its uses, most notably to a bird called the golden-cheeked warbler. A close relative of the more widespread yellow warbler, this species can be recognized by appearance (dark body, yellow face with black eye stripe), by song (“bzzzz layzee dayzee”), and by location (remarkably, it nests only in central Texas). Most at home in extensive tracts of mixed woodlands, the golden-cheek feeds mainly on caterpillars and other insects found on deciduous trees. But it also has an absolute and specific requirement for mature Ashe junipers, aged twenty or thirty and up, that have begun to develop shredding bark. The female warbler uses these fibers, bound together with spiders’ silk, to build her soft, gray, perfectly camouflaged nest. As shaggy old junipers have become scarce, so have the golden-cheeks, which were granted emergency protection under the Endangered Species Act in 1990. Predation by blue jays from encroaching urban forests (Austin, San Antonio, Waco) and parasitism by cowbirds are compounding the problems, which do not offer easy solutions.

Golden-cheeked warbler

Ice Age Relics

White spruce

Ponderosa pine

The tensions between supply and demand also help to account for another little-noticed feature of the prairie landscape. You’ll be scooting across the flatlands when suddenly the way ahead is obstructed by an abrupt rise. As the road climbs the escarpment, the view tilts toward the light and a phalanx of bristling conifers appears against the sky. Why, you may well wonder, would an evergreen forest sprout on the top of a rocky ridge, smack dab in the middle of the prairies? Yet this phenomenon is repeated in dozens of places across the Great Plains, from the white-spruce forests of the Cypress and Black hills to the ponderosa pines of Pine Ridge to the junipers of the Caprock Escarpment, among many others.

These mysterious scarp woodlands are relics from the past. At the end of the last Ice Age, the climate was cool and damp, and a dense coniferous forest stretched across the breadth of the continent. A dark mantle of spruce extended from what are now the Canadian prairies south through the Dakotas into the central states, while pine woods appear to have flourished on the southern plains. But as the chill of the glaciation gradually lifted, the climate eased into a drier and warmer phase, marked by more frequent droughts, and the boreal forest was forced to retreat to the north. Within remarkably short order—a blink of the cosmic eye—the forests of the Great Plains either surrendered directly to grasses or else gave way first to deciduous trees and then to prairie.

By the time the transformation was over, coniferous forest could only be found on the crowns of the tallest breaks and ridges. High enough to catch the rain and snow, and cooler than the grasslands below, these uplands created a microclimate in which the trees could retain a toehold. The thin mineral soils of the ridges—more suitable for conifers than for grasses or other plants—probably also gave the trees an advantage. But the factor that made the biggest different to the scarp forests was their top-o’-the-world location. Historically speaking, the greatest threat to prairie woodlands, apart from prolonged drought, was the fierce heat of grass fires. Where better to find refuge than atop a natural firebreak, an outcropping of safety in a world of flame? The present distribution of scarp woodlands therefore probably represents the limits of wildfires past, a kind of high-tide line beyond which the danger did not pass.

> FOSSIL FORESTS

Relics of the late Ice Age forest are strewn across the Great Plains, rather like flotsam from an ecological shipwreck. In the Sweet Grass Hills of Montana, for example, stands of Rocky Mountain Douglas-fir are found alongside hybrid (white x Engelmann) spruce, growing just where they were left stranded thousands of years ago. The main populations of all three species are now far to the north and west, in the mountains and the boreal forest. Similarly, scientists working in Wyoming and Nebraska have discovered relict stands of hybrid poplars (cottonwood x balsam) in parts of the Niobrara Valley, where the two species had not been in contact since the late Pleistocene.

The distribution of these living fossils has helped researchers to get a sense of the extent of the prehistoric forest. For instance, the fact that there are moose in the Turtle Mountain/ Pembina Hills region of Manitoba and North Dakota has been taken as evidence that the northern plains were once covered by extensive woodlands. By the same token, the flora and fauna of the Black Hills, with their disjunct populations of white spruce, paper birch, moose, black bears, and other boreal species, speak of a time long past when coniferous forest flowed out of the Rocky Mountains and across the Great Plains.

But the late Ice Age is not the only geological episode that has left its mark on the present. There was also an era, roughly 5,000 years ago, when the climate was both moister and warmer than it is now. Under these conditions, southern-adapted species, including a round-eared, silky-haired rodent called the eastern woodrat, were able to migrate north. (More commonly known as a pack rat—from its habit of stuffing shiny objects into its nest—the woodrat looks like a handsome, oversized mouse and is not closely related to the introduced Norway rat.) Although most of the population subsequently retreated southward, a hardy remnant still persists on the wooded banks of the Niobrara River and its tributaries in north-central Nebraska, 100 miles (150 kilometers) from any other members of the species.

Trees on the Move

For the woody plants that grew down on the grasslands, by contrast, there was no chance of escape. Despite a variety of adaptations for withstanding occasional burns—corky, fire-resistant bark (bur oak); seeds that are stimulated by heat (ponderosa pine); roots that put out new shoots to compensate for fire damage (many poplars and oaks)—few species of trees can survive frequent, intense fires. Grasses, by contrast, are basically born to burn. Not only do they produce a tinder-dry thatch of dead foliage that lights with the slightest spark, but they are equipped to rise from their own ashes. The buds, or meristems, from which they put up new growth are tucked down at the surface of the ground, where they are protected from serious harm. But woody plants, which are inclined to reach for the light, hold their buds on the tips of their branches, where they are exposed to the flames and are sorely vulnerable to fire damage.

Eastern red cedar

In the days of the buffalo prairie, frequent grass fires conspired with severe drought and occasional intense grazing to limit the spread of woody plants. In the sometimes-lengthy interludes between die-backs, trees and shrubs were often able to take advantage of cool, moist weather to extend their reach onto the grassy plains. But no sooner were the trees established than some random bolt of lightning would set the prairies aflame, killing shrubs and most trees except in the humid coulees and river valleys. On the tall-grass prairies, in particular, where catastrophic droughts were relatively infrequent, trees and shrubs might have taken over completely if it hadn’t been for the erratic but inevitable return of lightning.

Prairie fires were also set by Native people, who used burning as a tool to hold back the brush and maintain the grasslands as pasture for bison. But with the end of the buffalo ecosystem and the introduction of agriculture, prairie fires were suppressed and trees began to make a slow but steady advance. This expansion of woody vegetation has now been documented in almost every ecoregion across the Great Plains, from the Aspen Parklands of central Alberta (where a 60 percent increase in the area of brush was noted between 1907 and 1966) to the Flint Hills of Kansas (where patches of woodland protected from burning have enlarged by 250 percent since the 1850s) to the dry grasslands of west Texas (where the area covered by mesquite has more than tripled locally in just over a century). At the same time, various species of junipers are intruding on western rangelands, ponderosa pines have expanded from the Niobrara River valley into the Nebraska Sand Hills, and dense stands of eastern red cedar dominate the once-grassy slopes of Iowa’s Loess Hills. These examples could be multiplied many times over.

Extrapolating from local experience to calculate the effects on the Great Plains as a whole has not proven to be simple. Estimated area of presettlement woodlands minus acreage lost to clearing and other development plus postsettlement expansion of woody growth equals the sum of many unknowns. Still, the available evidence strongly suggests that the Great Plains region is now more heavily wooded than it was two hundred years ago. The big, unanswered question is, why? Some researchers have suggested that the changes began back in the days of the cattle barons of the nineteenth century, when the prairie was badly damaged by overgrazing. As the hold of the grass was weakened, patches of bare soil were exposed, creating openings where woody plants could grow. Once the brush was established, it was able to expand. Or perhaps the cattle not only broke the sod but also sowed the seeds by ingesting the fruits of trees and shrubs (notably, honey mesquite) and distributing them in their droppings. Alternatively, it is possible that global, rather than local, forces have been at work. Recent evidence suggests that rising concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, due to the burning of fossil fuels, may be encouraging the growth and expansion of trees and shrubs by giving them a physiological advantage over nonwoody plants. But whatever other factors have been involved, the suppression of the natural fire regime has certainly played a central role in encouraging the intrusion of woody plants into the grasslands.

In the Riparian Zone

The transformation of grasslands into woodlands is far from trivial. It represents the difference between ground squirrels and tree squirrels, meadowlarks and robins, sharp-tails and ruffed grouse, between the stripped-down economy of the drylands and the richer options of a more sheltered, and sheltering, wooded environment. Of all the habitats on the Great Plains, none is more biologically productive—or more subject to disturbance—than the sinuous stands of trees and shrubs that line the major creeks and rivers. Although these riparian forests occupy only about 1 percent of the region, they provide living space for somewhere between 60 and 90 percent of the species of vertebrates (reptiles, amphibians, mammals, and birds) that occur on the prairies. For example, researchers working in northeastern Colorado were amazed to discover that 82 percent of all the local birds could be found down by the river. This finding helps to account for the delight of walking along a prairie river on an early morning in spring, as a dozen different bird songs shimmer above the canopy. For anyone who has experienced this pleasure, it will come as no surprise to learn that, in both numbers of species and numbers of individuals, these woodlands are home to some of the richest avian communities in North America.

A pair of yellow warblers tend their nest.

Arthur Savage photo

But the resources of the riparian zone do more than provide habitat for an abundance of wild animals and birds. Over the years, they have also proven highly attractive to humans, from the seminomadic people of the Plains Woodland tradition, who gardened along creeks in Colorado some 2,000 years ago, to the village-dwelling Mandans and Hidatsas, who, as recently as the 1880s, were growing corn, beans, and squash in plots along the Missouri River and its tributaries. With the intrusion of industrial society, the demands on the riparian zone have grown ever-more intense, as we look to the river valleys for farmland, rangeland, roadways, reservoirs, and river-view subdivisions. When these localized impacts are overlain on the global effects of fire suppression and climate change, the riparian community can be expected to respond in conflicted and complex ways.

Even the most innocent changes can trigger profound effects. For instance, what could look less stressful than a herd of cud-chewing cattle bedded on a riverbank, watching the water slip quietly past? Yet wherever they are present, cattle present a major threat to the health of riparian ecosystems. Unlike the native-born bison, which were well adapted to life on the dry plains, cattle evolved in more temperate environments and are drawn to treed valleys in search of water, shade, and forage. Although moderate grazing, by a small number of cattle for a short period of time, may not cause noticeable harm, heavy grazing inevitably leaves deep scars. Too many hooves in too little space soon pound the place to death, as the animals foul the water, destabilize the banks, and trample or chew the upcoming crop of woody plants. Traditionally written off as sacrifice areas by the cattle industry, riparian woodlands have only recently been appreciated as a rich resource for wild animals and plants. Thanks to this new awareness, range managers are promoting the use of artificial water points, streamside fencing, and other strategies to protect these “hot spots” in the living landscape.

The sparky black-billed magpie is a familiar resident of woodlands across the plains, from the riparian zone to farm shelterbelts and urban plantings. A bright-eyed opportunist that eats both plant and animal foods—including songbird eggs and young—the magpie is despised by people who do not understand the role of predation in the ecosystem.

Unfortunately, damage caused by other means is often more difficult to correct. In the central United States, for example, corridors of hardwood forest once spread across the broad floodplains, or bottomlands, of rivers and creeks, including (among others) the Milk, the Marias, the Wildhorse, and the mighty Missouri. The riparian forests of the Missouri River, for example, opened out in the Dakotas and, like the river itself, grew broader and more majestic as they flowed south, expanding from a width of about half a mile (800 meters) in the north to a span of almost 19 miles (30 kilometers) as they neared the river’s mouth. Today, this irresistibly flat and fertile plain has been mostly converted to farms. Between the Nebraska state line and the Mississippi River, more than 80 percent of the lands that were forested before settlement are now planted to crops like corn and sorghum.

Farther upstream in the Dakotas, the outcome has been similar, though the means have been more complex. Here, too, forests have been lost to clearing: for instance, almost 60 percent of the native woodlands between the Dakotas’ Garrison and Oahe dams are now under cultivation. As for the remainder, most of the once-wooded floodplain now lies under the waters of lakes Sakakawea and Oahe and other impoundments. Although the shores of the reservoirs are fringed with patches of brush, these fragmented woodlands are neither as extensive nor as diverse—nor as rich in species of birds—as the original forests were. And even in places where remnants of the native forest have survived (for instance, along undammed stretches of the river west of Williston, north of Bismarck, and east of Yankton), things are not looking good. The problems first surfaced in the mid-1970s, when an analysis of cores from trees in the Garrison-to-Bismarck stretch of the river, downstream from the Garrison Dam, showed that they were not growing as quickly as they had twenty years earlier, before the dam was constructed. Somehow or other, the impoundment of the river was affecting the health of riparian ecosystems over distances of as much as 60 miles (100 kilometers).

Box elder/ Manitoba maple

How could a stationary wall of earth and concrete exert this kind of influence? The answer was that it was doing what it had been designed to do: controlling the flow of the river and preventing flooding. By depriving the riparian forests of a well-timed influx of water from spring floods, the dam had cast a shadow over them. In response, all the major species of trees in the forests, including green ash, box elder (or Manitoba maple), and American elm, were suffering from reduced rates of growth. And then there were the cottonwoods.

The dominant trees of the riparian zone across the prairies—and often the only species on the arid plains of Alberta, Montana, and other points west— cottonwoods are dependent on the energy and flux of flood for their very survival. Each spring, a typical grove of cottonwoods pumps out billions of cottony, wind-borne seeds, most of which end up drifting forlornly around the country. Only a tiny fraction find the conditions that they need for germination and growth: bare soil, full sun, and plentiful moisture. Where better to meet these requirements than in the wake of a spring flood? As the river recedes from the floodplain, a terrain of newly deposited sandbars and clean-scoured banks is exposed, creating ideal conditions for cottonwood seeds to sprout. (That is why cottonwoods often grow in bands and arcs of same-age trees, each representing a historical moment of opportunity.) But if spring floods are constrained and seed beds are not produced, the trees lose their only chance at reproduction for an entire year.

As Wallace Stegner once pointed out, “western history is a series of lessons in consequences,” and the consequences for cottonwoods have, for the most part, not been good. Because their rate of reproduction is reduced, the trees can’t compensate for natural mortality, and many populations are collapsing. (Cottonwoods are old by age thirty, and few last longer than a century.) The surviving stands of cottonwoods along the Missouri, Bighorn, Milk, South Saskatchewan, and several other rivers are all dying off, and there are few ambitious young saplings to take their places. As early as 1981, for instance, just a couple of decades after the Waterton and St. Mary rivers of southeastern Alberta were dammed, the number of cottonwoods along their banks had declined by 23 percent and 48 percent, respectively. By contrast, along the neighboring Belly River, which was not restrained by dams, the cottonwoods continued to reproduce and sustain themselves.