1

‘… the Millers – a family’

Even the beginnings were deceptive. To comfortable middle-class households in Torquay, the airy coastal resort in Devon where Agatha was born, the end of the nineteenth century seemed to be a Victorian afternoon. They did not notice that twilight was stealing over the terraces, the gardens and the pier. Agatha’s own family, the Millers, looked equally prosperous and secure, but their fortunes, too, were imperceptibly growing shakier. And, like most families, the Millers were not as ordinary as they first appeared. In fact, they were decidedly unconventional.

Agatha was the youngest of three children. Madge, her sister, had a passion for disguise that exasperated her teachers and, eventually, her husband, as much as it entertained her friends and bewildered her visitors. Monty, Agatha’s brother, had a different if related talent – for hitting on wild schemes into which he would draw harmless bystanders, to no one’s profit but everyone’s delight, particularly that of the women. Frederick, Agatha’s father, was a charming, nonchalant American, keen on amateur theatricals, fussy about his health but not, until too late, about his investments; her mother, Clarissa, known always as Clara, was capricious, enchanting, and said to be psychic. She was also prone to spiritual and intellectual recklessness. Agatha adored them all.

Frederick and Clara had a romantic and complicated history. Clara’s childhood was a mixture of comfort and insecurity that made her an especially possessive mother; this, in turn, fed Agatha’s devotion, which for a time was to become obsessive. To understand Agatha, it is necessary to know her parents and, equally important, the two women who shaped their lives: her grandmother and step-grandmother, Mary Ann and Margaret.

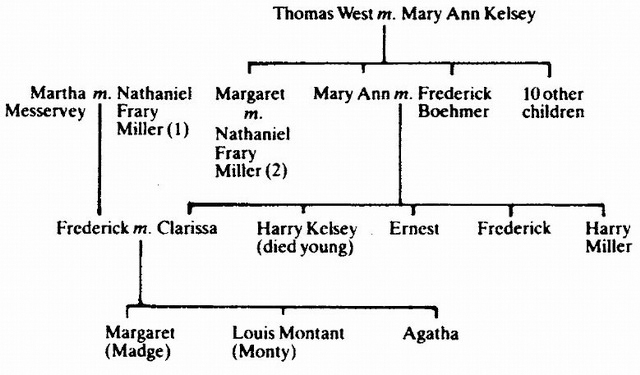

The family was connected as neatly as characters in a detective story. These links are clearer if they are described like the settings for Agatha’s plots, with the help of a plan:

Mary Ann and Margaret West and their ten brothers and sisters were orphans and were brought up on a farm in Sussex by childless relations. In 1851 Mary Ann met Captain Frederick Boehmer of the Argyll Highlanders, who pressed her to marry him. Since he was thirty-six and she sixteen, her family demurred but Captain Boehmer argued that, as his regiment was about to be sent abroad, the wedding should take place at once – and it did. Mary Ann and Frederick had five children in quick succession (one died as a baby) of whom the only daughter, Clara, was born in Belfast in 1854.

In April 1863 Captain Boehmer, then stationed in Jersey, was thrown from his horse and killed, at the age of forty-eight, leaving Mary Ann, now twenty-seven, with four children to support as best she could. She was an excellent needlewoman and, by embroidering pictures and screens, slippers, pincushions and the like, augmented her husband’s tiny pension. As Frederick had lost what savings he had in some vague speculative venture, Mary Ann had a great struggle to make ends meet. It is little wonder that in an entry in a family ‘Album to Record Thoughts, Feelings, etc.’ known as the ‘Confessions’, written eight years after Frederick’s death, she gave her state of mind as ‘Anxious’.

Meanwhile, Mary Ann’s elder sister, Margaret, had been working in a large hotel in Portsmouth, a post found by an aunt who had for many years been its forceful and greatly respected receptionist. Margaret, already formidable herself, married when she was twenty-six, in April 1863. Her husband, Nathaniel Frary Miller, a widower, had been born in Easthampton, Massachusetts, and had become a successful businessman, a partner in the firm of H.B. Chaflin in New York City. Nathaniel and his first wife, a hospital nurse, had only one child, a son, Frederick Alvah Miller. After his mother’s death, Frederick was brought up mostly by his grandparents in America, but, after his father remarried and settled in England, where his firm had business in Manchester, Frederick visited Nathaniel and Margaret there. Here he met Clara.

It was a fortnight after Margaret’s marriage to Nathaniel that Mary Ann lost her husband. Margaret wrote immediately to her younger sister, offering to take one of the four children and bring it up as her own, and Mary Ann, now despairing, decided that Clara should go to live with her aunt and uncle in the North. The little nine-year-old was lonely and homesick in her new surroundings and Clara always believed Mary Ann had sent her away because she cared more for the boys, rather than, as seems likely, because she felt it would be less easy for a girl to make a career for herself. Clara’s chief consolation was her favourite book, The King of the Golden River, which she brought with her from Jersey. She would read aloud to her uncle Nathaniel the story of its hero, a lonely but determined little boy, who conquered his desolation by being sensible and considerate. Clara, quiet and imaginative, knowing her aunt and uncle were being kind to her but feeling bereft and misunderstood, treasured this book all her life, as Agatha did in her turn.

Clara’s upbringing and tastes were those of an intelligent but sheltered late-Victorian girl. When she was seventeen, she too listed her likes and dislikes in the ‘Confessions’. Her ‘favourite qualities in man’, she said, were ‘firmness, moral courage and honour’, and, in woman, ‘refinement, frankness and fidelity’. Her favourite occupation was reading and talking, her chief characteristic ‘a great love for children’, and ‘the fault for which she had most toleration’ (in this case her own), ‘reserve’. But the young woman whose ‘present state of mind’ was ‘wishing for a long dress’ and who admired Landseer and Mendelssohn, Tennyson, Miss Nightingale and the novels of Miss Mulock, nevertheless had a more robust and merry side. She gave her favourite food and drink as ‘Ice-cream; American soda water’, her favourite fictional heroine as Jo, the energetic tomboy in Little Women, and to the question ‘If not yourself, who would you be?’ she replied firmly, ‘A school-boy.’

When Clara came to live with the Millers, Frederick, Aunt Margaret’s American stepson, was seventeen years old and the cousins became fond of one another. Although there was only eight years’ difference between them, it seemed a larger gap: Clara lived quietly at home in England, while Frederick, after school in Switzerland, had enjoyed a lively, to Clara a dizzy, time in America. As one of his friends later told Agatha, ‘He was received by everyone in New York society, was a member of the Union Club, and was widely known, and there are scores of present members of the Union Club, mutual friends of ours, who knew him, and were very much attached to him.’ After Frederick’s marriage, his and Clara’s names appeared in the New York Social Register; in his own copy Frederick’s blue pencil ticked the names of his many New York friends and acquaintances and others in the best families of Philadelphia and Washington.

The sort of life Frederick led is described in the novels of Henry James and Edith Wharton. The American upper-class society in which he moved was small and intimate – some nine hundred families only are listed in the Social Register of 1892 – and much time was taken up with visiting friends and relations, reading newspapers and writing notes at the Club, dining, dancing, going to the theatre and (less frequently for those who were not devotees) concerts and galleries, playing tennis, croquet and cards, smoking (a serious pastime) and watching horses racing or, alternatively, yachts. Frederick Miller was not, however, one of the moody young fellows depicted in novels of the time, but, in Agatha’s words, ‘a very agreeable man’. Indeed, in his own joking entry in the ‘Confessions’, written when he was twenty-six, he gave an accurate picture of his temperament – easy-going, philosophical, hardly energetic. His favourite occupation was described as ‘doing nothing’, his chief characteristic, ‘ditto’. The characters in history he most disliked were Richard III and Judas Iscariot, his favourite heroes in real life Richard Coeur de Lion and ‘a country curate’. His pet aversion was ‘Getting up in the morning’, his present state of mind ‘Extremely comfortable, thank you’, and to the question, ‘If not yourself, who would you be?’ he placidly replied, ‘Nobody.’ Only one question had a really enthusiastic answer and that concerned his favourite food and drink, where he crowded into a two-line reply: ‘Beefsteak, Chops, Apple Fritters, Peaches, Apples. All kinds of nuts. More peaches. More nuts, Irish stew. Roly Poly Pudding’, and, an asterisked afterthought, ‘Bitter Beer.’

In the same entry Frederick described the characteristics he most admired in women as ‘amenibility to reason’ (his spelling, like that of Madge and, especially, Clara and Agatha, was often erratic), ‘with a good temper’. These were his little cousin’s qualities. She was devoted to Cousin Fred, who had been the first person to compliment her, at the age of eleven or so, on her beautiful eyes, and who sent her when she was seventeen a volume of Southey’s poems, bound in blue and gold and inscribed: ‘To Clara, a token of love’. Clara, for her part, sent Frederick letters and poems and, later, notebooks embroidered with daisies, monograms in gold thread, inscriptions and, most ambitious, a red heart stuck with two arrows. She took pains over these tributes; she was a much less skilful needlewoman than her mother and in one piece of embroidery was obliged to leave off the last letter of Frederick’s name, having misjudged the space available. She also gave him serious and sentimental poetry; a maroon and gold album contains the verse, mostly about love and death, which she composed during their engagement. Occasional corrections in Frederick’s hand show that he not only conscientiously read his cousin’s poetry but here and there improved it.

The most lively verse in that collection was a satirical view of marriage, ‘The Modern Hymen’, which Clara described as being a purely egotistical arrangement: ‘For the Bride, fair beauty, For the Bridegroom, wealth. Two in one united, And that one is – Self.…’ Clara’s and Frederick’s marriage was not at all on these lines. She had refused his first proposal because she thought herself to be ‘dumpy’ and he, though believed to be rich because he was an American, enjoyed a comfortable but not enormous income.

The cousins were married in April 1878; Frederick was thirty-two and Clara twenty-four. A month later, in Switzerland, she wrote a long, rhapsodic poem for him, asking God to send her ‘an angel friend’, whom she could charge to protect and support ‘her darling’; the gift to Frederick is the more touching because it has at the foot a slightly botched attempt at a drawing of an angel and a request to ‘excuse this piece of paper … the only thin piece I had left’, as well as enclosing two dried edelweiss, a gentian, a violet and some clover. These, with the notebooks, Frederick always kept by him.

Margaret Frary Miller, Frederick and Clara’s first child, was born in January the following year, in Torquay, where the Millers had taken furnished lodgings. Soon after Madge’s birth her parents took her to America, so that Frederick could present his wife and baby daughter to his grandparents, and it was thus that the second child, a boy, was born in New York in June 1880. This was Louis Montant, named after Frederick’s greatest friend. The Millers and their two children then returned to England, where they expected to stay only a short time before going back to America to live. Frederick, however, was suddenly obliged to return to New York to see to various business matters and suggested that while he was away Clara should take a furnished house in Torquay. With the help of Aunt Margaret, now a widow, Clara accordingly inspected two or three dozen houses but the only one she liked was for sale, rather than for rent. Despite – or perhaps because of – the restrained and ordered environment in which she had been brought up, Clara was determined and impetuous, and she immediately bought the house, with the help of £2,000 which Nathaniel had left her. She had felt at ease in it at once and when its owner, a Quaker called Mrs Brown, had said, ‘I am happy to think of thee and thy children living here, my dear’, Clara felt it was a blessing. Frederick was somewhat taken aback to discover that his wife had bought a house in a place where he expected them to stay a year or so at most but, always good-natured, he fell in with her wishes.

The house was Ashfield, in Barton Road. It has long been demolished but some impression of it can be had from Agatha’s recollections and those of her contemporaries and from photographs taken at the turn of the century. Ashfield was large and spreading, like other Torquay villas of its kind, built for the sizeable families of the professional middle class, who needed plenty of spacious rooms to hang with draperies, cram with furniture and stuff with interesting objects which they liked, or liked to display. Such houses were no trouble to heat, because fuel was cheap, or to clean and maintain, because servants were inexpensive, with enterprising and ingenious plumbers, glaziers, carpenters and masons in abundant supply. Ashfield was an attractive and unusual house; a rectangular two-storey part, with wide sash windows, adjoined a squarish three-storey section, with tall windows, some of those on the ground floor having coloured glass in the upper part, while the lower sections opened on to the garden. There was a multiplicity of chimneys; trellis-work and climbing plants covered the walls. The porch, which was large and topped with window boxes, was entirely shrouded with creeper. Attached to the house was an airy conservatory, full of wicker furniture, palm trees and other spiky and exotic plants, and at ten-foot intervals along the edge of the lawn, where it bordered the gravel, were huge rounded pots of hyacinths, tulips and other plants in season. A second, smaller greenhouse, used for storing croquet mallets, hoops, broken garden furniture and the like, and known as ‘Kai Kai’, adjoined the house on the other side. (Towards the end of her life Agatha described this greenhouse in Postern of Fate.)

The garden seemed limitless to Agatha, most of whose childhood world it composed. She described it as being divided in her mind into three parts: the walled kitchen garden, with vegetables, soft fruit and apple trees; the main garden, a stretch of lawn full of trees – beech, cedar, fir, ilex, a tall Wellingtonia, a monkey-puzzle tree and something Agatha called ‘the Turpentine Tree’ because it exuded a sticky resin; and, last, a small wood of ash trees, through which a path led back to the tennis and croquet lawn near the house. Ashfield was, moreover, at the end of the older part of the town, so that Barton Road led into the lanes and fields of the rich Devon countryside. The houses and gardens seemed immense and that was how Agatha remembered them when she was grown up – but Ashfield was certainly big.

It was as well that the house was spacious, since Frederick had a mania for collecting. Torquay being a fashionable resort, patronised by people with money, taste and plenty of spare time, it had attracted a number of dealers, into whose smart shops he would make a detour on his daily walk to the Yacht Club. The shopkeeper who did best was J.O. Donoghue, of Higher Union Street, whose lengthy bills give a detailed picture of Frederick’s purchases of coffee tables, card cases, plaited baskets, salts, oriental jugs and jars, china plates, cut-glass candlesticks, paintings on rice paper, muffineers and innumerable pieces of Dresden china. The stack of bills preserved among Frederick’s papers also shows the extent of the Millers’ domestic establishment and hospitality. Five-course dinners were prepared daily by Jane, the cook, with a professional cook and butler hired for grand occasions, when at each course a choice of dishes would be presented. Clara kept a book of ‘receipts for Agatha’, which indicates the richness and expense of the food that was served: fish pies, for instance, were made of filleted sole layered with oysters (though there was a footnote saying ‘Best brand of tinned oysters “Imperial”’) and directions were given for preparing truffles to add to meat or chicken, for making breakfast dishes of cold salmon and of kidneys and mushrooms, for dishes of quail, splendid savouries, and various complicated salads, smooth creams and junkets. The only really economical recipe, for macaroni cheese, instructed the reader to ‘get the macaroni at a shop in Greek Street, Soho, kept by an Italian’ and carried the terse comment ‘Not very good.’

Into this well-equipped household Agatha was born on September 15, 1890. She was the much-loved ‘afterthought’; her mother was thirty-six, her father forty-four and there was a gap of eleven years between Agatha and Madge and ten between Agatha and Monty. Madge was by now a boarder at Miss Lawrence’s School in Brighton (later to become the celebrated girls’ boarding school Roedean) since this accorded with Clara’s current view of what should constitute female education. Madge’s letters to her baby sister – ‘My dear little chicken … Who do you get to make you a big bath of bricks in the schoolroom now that your two devoted slaves have left for school to learn their lessons?’ – reflected her gregarious and comic nature. She was a tumbling, bouncing girl, not beautiful but with an attractive, mobile face and an engaging grin. The only wistful note in her entry in ‘Confessions’ was her answer to: ‘If not yourself, who would you be?’ to which she replied, ‘A beautiful beauty.’

Madge adored jokes, pranks and disguises and Agatha was awed and delighted by her sister’s exploits. She talked with amazed pride of the time when Madge dressed up as a Greek priest to meet someone at the station and of the occasion when, having come to Paris to be ‘finished’, she accepted a dare to jump out of the window and landed on a table at which several horrified Frenchwomen were taking tea. Madge would thrill her sister by spicing affectionate play with a dash of spookiness, saying solemnly, ‘I’m not your sister,’ looking for a moment like a stranger, or, in an even more terrifying version of this game, putting on the silkily ingratiating voice of the imaginary madwoman Madge and Agatha called ‘The Elder Sister’, who lived in a cave in the nearby cliffs, and uttering the horribly unreassuring words, ‘Of course I’m your sister Madge. You don’t think I’m anyone else, do you? You wouldn’t think that?’

It is much harder to catch a glimpse of Agatha’s brother, Monty. Here and there, in the first dictated draft of the part of her autobiography that deals with her childhood, Agatha alluded to the fact that ‘at about this time, Monty disappeared from my life’; as it was, he hardly seems to have been there at all. This is partly because, when Agatha was young, Monty was at Harrow and when she was older he had vanished abroad. He was not a scholar – he left Harrow without passing his examinations – but his winning disposition helped him to survive. Agatha told the story of Monty’s being the only boy allowed to keep white mice at school, since the Headmaster had been induced to believe that Miller was especially interested in natural history. Her picture of him was, as one would expect, of someone who, by virtue of his being a boy and ten years older, led a strange and exciting life of daring exploits in boats and later in motor cars, in which he would sometimes disdainfully allow his little sister to take part.

Things cannot have been easy for Monty, in a circle of four forceful women – his energetic and argumentative elder sister, shrewd impulsive mother, and two formidable grandmothers. A photograph shows him, in an ill-fitting buttoned uniform, with a sullen expression on his handsome face; he might be any age from nine to nineteen and he looks bored and unhappy. But other pictures show Monty at his most gay and irrepressible: we see him, in smoking jacket, top-hat and huge leather boots, sitting in ‘Truelove’, the tiny wheeled horse and carriage with which the children played, cheering on a puzzled goat which has been attached to the reins. Monty has a look that is simultaneously wild and self-indulgent.

In his portrait, painted when Monty was nineteen or so, he seems calmer but somehow unconvincing, as if he were not sure whether to look foppish, quizzical, or rakish. His entry in the ‘Confessions’ (which he forgot to sign) conveys a similar impression of uncertainty. His remarks were those of someone trying to be amusing, with neither the panache nor the wit to carry it off: ‘Your favourite heroes in real life?’ – ‘Fenians’; ‘Your present state of mind?’ – ‘Oh my!’; ‘Your favourite qualities in man?’ – ‘Being a good fellow generally’; and – a clue to the fact it is Monty who is writing – ‘Your idea of misery?’ – ‘Borrowing money.’ There was something melancholy about Monty and, though his influence on his younger sister was much less direct and obvious than that of Madge, he nevertheless presented a worrying puzzle to Agatha.

Agatha Mary Clarissa was named after her mother and grandmother, the name of Agatha, she believed, being added by Clara, with her usual agility, as a result of a suggestion made on the way to the christening. (One of Clara’s favourite novels was, moreover, Miss Mulock’s Agatha’s Husband.) During the course of Agatha’s life, she was to acquire, or adopt, a number of different names and titles; to her friends and family (except those close relations who later called her ‘Nima’, her grandson’s corruption of ‘Grandma’) she was always ‘Agatha’. As her first publisher told her in 1920, it was an unusual and therefore memorable name – and that is what we will call her here.

Frederick’s collection of bills also gives some impression of the furniture, books and pictures amongst which Agatha grew up. Some of the better furniture was sold in the years after her father’s death, when her mother’s circumstances were considerably reduced, but a good deal of it, including many of the lamps, screens and pictures, and much of the china, cutlery and glass, was used to furnish the houses in which Agatha subsequently lived. As she said herself, her father’s taste in pictures did not match his discrimination in buying furniture. The fashion of the eighteen-eighties and eighteen-nineties was to hang as many pictures as possible on whatever wall space was available and this Frederick proceeded to do, with vague oils, Japanese caricatures, pastels on copper and masses of engravings, including one called ‘Weighing the Deer’, of which he was particularly fond. Certain cherished objects were assigned to those members of the family who would eventually inherit them. (Clara’s Aunt Margaret would write names of the future beneficiaries on the backs of the canvases.) Agatha’s particular inheritance was ‘Caught’, an oil of a woman catching a boy in a shrimping net, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1884 and acquired by Frederick ten years later for the sum of £40. In the same year, when Agatha was four, her father commissioned a local artist, N.H.J. Baird, to paint the family dog, an exercise which was regarded as so successful that Mr Baird was subsequently invited to paint Frederick, Agatha, Monty, Madge, and Agatha’s nurse. When, at the age of seven, Agatha was asked to name her favourite poets, painters and composers in the ‘Confessions’, she loyally put Baird’s name alongside those of Shakespeare and Tennyson.

The focus of Agatha’s life as a small child was ‘wise and patient Nanny’, the cook Jane, and successive parlourmaids. Her recollections of these companions date from an early age. Unusually, too, her Autobiography described what Nursie and Jane looked like, her nurse with ‘a wise wrinkled face with deep-set eyes’, framed, as in Mr Baird’s portrait, by a frilled cambric cap, and Jane, ‘majestic, Olympian, with vast bust, colossal hips, and a starched band that confined her waist’. Nursie represented ‘a fixed point, never changing’. For instance, her repertoire of six stories did not vary, whereas Clara’s were always different. Clara, unlike Nursie, never played the same game twice; as Agatha wrote of her mother’s tales and games, their unpredictability sometimes shocked her but she also felt the enchantment of the perpetually unknown. Nursie’s religious beliefs were firm. She was a Bible Christian, devoutly keeping the Sabbath by reading the Bible at home. Clara, by contrast, experimented with various schools of religious thought: she had nearly been received into the Roman Catholic Church; next she tried Unitarianism, which in turn gave place to Theosophy and then, briefly but keenly, to Zoroastrianism. She was at one point deeply interested in Christian Science and occasionally attended Quaker meetings. Clara broke the rules – she and Agatha would gaily gather up all the towels in the house to play with – while Nursie enforced them. When Agatha was four or five, Nursie returned to Somerset. Agatha missed her desperately, for she had been the centre of order, calm and stability.

So was Jane, who presided over the kitchen. There she was, massive, placid, always gently munching on some delicious scrap, providing regular meals at regular times, and bits and pieces in between. It is not surprising that food was always a pleasure and a solace to Agatha and that she is remembered for the ample meals she offered, the expertise with which she would make éclairs and mayonnaise, and the delight she took in food that was served to her. Jane taught Agatha to make cakes, ‘some with sultanas, and some with ginger,’ as she wrote proudly to her father when she was eleven, ‘and we had Devonshire cream for tea.’ She was passionately fond of cream: Devonshire cream on its own, eaten with a spoon; double cream mixed half and half with thick milk and drunk from a cup; or clotted cream put together with treacle to make ‘Thunder and Lightning’. This was real Devonshire cream, as thick as butter and as smooth, with a yellow crust and palest gold below, a simple but matchless taste, a slippery consistency and a flavour bland yet unlike anything else – just the sort of dish for which a lonely child might yearn.

Agatha was, moreover, energetic and intelligent; she got hungry and bored, in spite of the games and stories she invented, and she remained a skinny child. Monty called her ‘the scrawny chicken’. Meals, punctually served, were benchmarks in the day and the ceremonies of presenting and consuming food were fascinating, especially since she was orderly and fond of ritual. Throughout her life she served formal meals as they were composed in her childhood, with silver and glasses correctly placed, flowers arranged, napkins folded, course succeeding course. A meal was a celebration.

Liking the way things were arranged, Agatha was also interested in the way people were ordered. She was to discover as she grew up the fine gradations of Torquay society but her first inkling of a hierarchy was in the household at Ashfield. With her sharp ear for words and phrases, she noticed forms of address: cooks were always ‘Mrs’, housemaids equipped with ‘suitable’ names (even if they did not arrive with them), like Susan, Edith, and so on, and parlourmaids, who ‘valeted the gentlemen and were knowledgeable about wine’, had names sounding vaguely like surnames – Froudie was one of the Millers’ parlourmaids – to go with their ‘faint flavour of masculinity’. Duties, too, were clearly allocated and, while there were few complications in Ashfield’s small household of three servants, from time to time Agatha would be aware of friction between the nursery and the kitchen. Nursie, however, was ‘a very peaceable person’.

As the servants deferred to Agatha’s parents (Jane, when asked to recommend a dish, would not dream of suggesting anything except, non-committally, ‘A nice stone pudding, Ma’am?’), so the lower servants genuflected to those in higher authority. Agatha was deeply impressed, as a child, by the reproof which Jane (addressed by the other servants as Mrs Rowe) administered to a young housemaid who rose from her chair prematurely: ‘I have not yet finished, Florence.’ A sensitive child, she could spot where power lay and, as children do, grew skilled at managing complex relations with a number of adults with whom she had understandings of varying degrees of complicity. Agatha knew about the servants’ world, not only because these were the adults with whom she spent a fair amount of time but also because she needed to keep her wits about her in order to avoid trouble and interference, obtain attention and titbits, and know what was going on.

Like most children, too, she was interested in the execution of practical tasks – the way pastry was made, ironing done, fires laid, boots blackened and, as Agatha observed, ‘glasses washed up very carefully … in a papier-mâché washing-up bowl’. She acquired a proper respect for the efficient exercise of these domestic skills, enhanced by Clara’s instilling into her that servants were highly trained professionals, versed not only in the intricacies of whichever part of the household they managed but also in the correct relations that should prevail between themselves and the people for whom they worked. Agatha emphasised this point in her Autobiography, since she was aware that the world before 1939 which she was describing was quite different from that of many of her readers, who might be baffled by the nuances of these domestic relationships.

To Agatha her mother was an extraordinary and magical being. Now in her late thirties, Clara supervised her household and her husband with natural authority, reinforced by experience. She knew and thought about her husband and children sufficiently keenly for them to believe that she had second sight (Madge once said to Agatha that she didn’t dare even to think when Clara was in the room), an impression that must have been fortified by her fickle but profound interest in various bizarre philosophies. She still wrote poetry; one of her stories, with Callis Miller as a pseudonym, survived among Agatha’s papers. The narrator of ‘Mrs Jordan’s Ghost’ was the unhappy spirit of a dead woman, manifesting itself whenever a particular piano was played. The preoccupations of this forlorn soul – rippling music, an ominous verse, guilt and purification, a vaguely apprehended unknown Power, ‘the unwritten laws of this mysterious universe’ – were exactly what one would expect in a story by Clara. An exotic figure, looking in her later photographs drawn and astonished, she seemed to Agatha a charming mixture of waywardness and dignity, certainty and vagueness.

Agatha saw her mother at special times: when she was ill or upset; when she needed permission to embark on some rare adventure or wished to report on one; and after tea, when, dressed in starched muslin, she would be sent to the drawing-room for play and one of Clara’s peculiar stories – about ‘Bright Eyes’, a memorable mouse, whose adventures suddenly petered out, or ‘Thumbs’, or ‘The Curious Candle’, which Agatha later dimly remembered as having had poison rubbed into it (this tale too, came to an abrupt stop). It was then that she could study her mother’s ribbons, artificial flowers and jewellery. Small girls (as she recalled in Cat Among the Pigeons) are not immune to the spell of jewels and those belonging to an older woman are especially magical, for they represent all sorts of mysteries and transformations. In her Autobiography Agatha described Clara’s ornaments, although her list is thin in comparison with the pile of jewellers’ accounts among Frederick’s bills: for lockets and stars, brooches and fans, buttons, rings, scent bottles and card cases, and two of the items Agatha remembered, a diamond crescent and a brooch of five small diamond fish, bought, endearingly, during the last weeks before Agatha’s birth.

In Nursie, Jane, Clara and Madge, Agatha was surrounded by strong and influential women. Her father, kindly and interested in his daughter’s progress, had his own detached way of life. In the morning after breakfast he would walk down to the Royal Torbay Yacht Club, calling en route at an antique dealer’s, to see his friends, play whist, discuss the morning newspapers, drink a glass of sherry and walk home for luncheon. In the afternoon he would watch a cricket match, or go to the Club again and weigh himself (preserved among his papers is a sheet of Club writing paper, with such records of stones and ounces as: August 9th, p.m., blue suit, 14.0; September 13th, a.m., Pep. Salt., 14.0), before returning to Ashfield to dress for dinner. Frederick’s photographs show him stout and contemplative, and, in part because of his fashionable moustache and beard, he looked older than his years.

There were two other important and impressive women in Agatha’s childhood: her grandmothers Margaret and Mary Ann. Margaret, Clara’s aunt and Frederick’s step-mother, was known as Auntie-Grannie, while Mary Ann, Clara’s mother, was known as Grannie B. It was at Margaret’s house that the family gathered. After Nathaniel’s death she had moved from Cheshire to a large house in Ealing, filled with a great deal of mahogany furniture, including an enormous four-poster bed curtained with red damask, into which Agatha was allowed to climb, and a splendid lavatory seat on which she would sit, pretending to be a queen, ‘bowing, giving audience and extending my hand to be kissed’, with imaginary animal companions beside her. ‘Prince Goldie’, named after her canary, sat ‘on her right hand’ on the small circle enclosing the Wedgwood handle of the plug. On the wall, Agatha recalled, was an interesting map of New York City. Throughout her life Agatha maintained that a well-appointed and efficient lavatory, preferably of mahogany, was an essential feature of a house or an archaeological camp; she was delighted to discover in her house in Devon a room fitted with wooden furniture almost as magnificent as her grandmother’s.

Auntie-Grannie passed her days not in the drawing-room, ‘crowded to repletion with marquetry furniture and Dresden china’, nor in the morning-room, used by the sewing woman, but in the dining-room, its windows thickly draped with Nottingham lace, every surface covered with books. Here she would sit either in a huge leather-backed carver’s chair, drawn up to the mahogany table, or in a big velvet armchair by the fire. When Agatha was tired of the nursery and the garden, full of rose trees and with a table and chairs shrouded by a willow, she would come to find her grandmother, who would generally be writing long ‘scratchy-looking’ letters, the page turned so that she could save paper by writing across the lines she had just penned. Their favourite game was to truss Agatha up as a chicken from Mr Whiteley’s, poke her to see whether she was young and tender, skewer her, put her in the oven, prick her, dish her up – done to a turn – and, after vigorous sharpening of an invisible carving knife, discover the fowl was a squealing little girl.

This memory, like many of Agatha’s other recollections of her paternal grandmother’s house, was of fun and of eating. She described with great vividness each morning’s visit to the store cupboard; Margaret, like her stepson, was a collector but, as well as hoarding lengths of material, scraps of lace, boxes and trunks full of stuff, and surrounding herself with a profusion of furniture, she also assembled quantities of food: dried and preserved fruit, pounds of butter and sacks of sugar, tea and flour, and cherries, which she adored. (The ‘Confessions’ gives Margaret’s favourite food and drink as stewed cherries and cherry brandy and when she left Ealing thirty-six demijohns of home-made fruit liqueur were removed from her house.) She would dispense the day’s allocation to the cook, investigate any suspected waste, and dismiss Agatha with her hands full of treasure – crystallised fruit like jewels.

Mrs Boehmer, Grannie B., lived in Bayswater but made frequent visits to her sister at Ealing. Here Agatha saw her, and always on Sundays, when the family would assemble at Auntie-Grannie’s table for a large Victorian lunch: ‘an enormous joint, usually cherry tart and cream, a vast piece of cheese, and finally dessert’. Two of Clara’s brothers would be there, Harry, the Secretary of the Army and Navy Stores, and Ernest, who had hoped to become a doctor but, on discovering he could not stand the sight of blood, had gone instead into the Home Office. (Fred was with his regiment in India.) After lunch the uncles would pretend to be schoolmasters, firing questions at Agatha, while the others slept. Then there was tea with Madeira cake. On Sunday, too, the grandmothers would discuss and settle the week’s dealings at the Army and Navy Stores, where they had accounts and where, during the course of the week, Grannie B. would make small purchases and take repairs for Auntie-Grannie (who, Agatha suspected, discreetly added a small present of cash when reimbursing her sister). Agatha joined her grandmothers on some of these expeditions, which are recalled in her description of Miss Marple’s missions to the Army and Navy Stores in At Bertram’s Hotel.

Agatha’s Autobiography gives only the most general description of her grandmothers’ appearance. As widows usually did, they dressed in heavy black. Both seemed to Agatha extremely stout. Grannie B. in particular suffered from badly swollen feet and ankles, as Agatha was later to do, and her tight-buttoned boots were torture. In fact their photographs show that they were small women but to Agatha, a thin and bony child, they and the silky stuffs in which they were swathed must have appeared imposing. It was their conversation she remembered and recorded most clearly: good-natured bickering between the two sisters, each teasing the other over who had been more attractive as a girl – ‘Mary’ (or ‘Polly’, as Auntie-Grannie called Grannie B.) ‘had a pretty face, yes, but of course she hadn’t got the figure I had. Gentlemen like a figure.’ And Agatha drank in their gossip about friends who came to call: Mrs Barry, for instance, whom Agatha regarded with profound awe because she claimed to have been in the Black Hole of Calcutta. Though implausible, her story was so horrid that it fascinated the company.

These conversations were riveting to an imaginative child whose fancy careered ahead of her understanding and who was particularly susceptible to words. (On one occasion a farmer’s angry shout ‘I’ll boil you alive,’ when Agatha and Nursie wandered on to his land, struck her dumb with terror.) Especially interesting were the anecdotes of gallant colonels and captains, with whom Auntie-Grannie kept up ‘a brisk, experienced flirtation’, knitting them bed-socks and embroidering fancy waistcoats, and who made Agatha nervous with their heavy-handed archness and tobacco-laden breath. She remembered exceptionally clearly the remarks, deliberately made in her hearing, about the relationship between a retired Colonel in the Indian Army and the young wife of his best friend, who had retired to a lunatic asylum: ‘Of course, dear, it’s perfectly all right, you know. There is nothing at all questionable about it. I mean, her husband particularly asked him to look after her. They are very dear friends, nothing more. We all know that.’

Margaret seems to have been a more forthright and colourful character than her younger sister; certainly Agatha’s Autobiography contained many references to the opinions, precepts and warnings handed out by her Ealing grandmother, whereas she recalled little of the views of her quieter counterpart in Bayswater. But the serene and affectionate Mary Ann, who never remarried, busying herself with her needle and giving her attention to her three sons, and the more striking Margaret, with her pithy wit and scorn of humbug, thoroughly interested in what the world was thinking and doing, surrounded by cupboards and drawers full of bits and pieces, both provided models of what an old lady might be like. From their characters Agatha was later to draw much that was instructive and entertaining.