MICHAEL

COORENGEL

&

JEAN-PIERRE

CALVAGRAC

THEATRICAL

APARTMENT

‘As much as it is about aesthetics, interior design is about logic and balance. It is important to get it to a point where most people have to admit that it works. It is like cooking or music – when the balance of elements is there it can’t be denied.’

Michael Coorengel

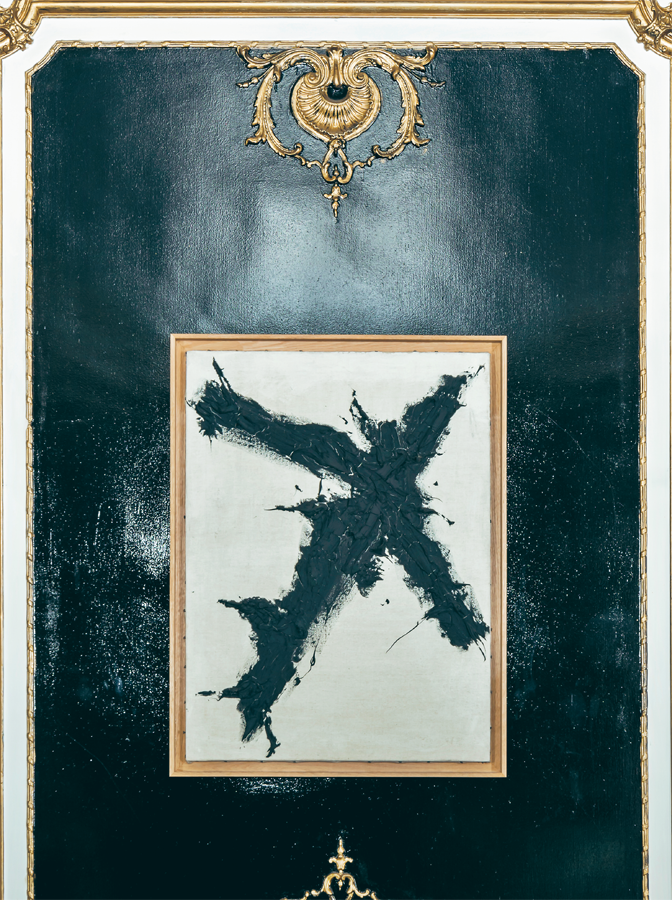

In the room with gold leaf mouldings, an abstract painting by Michael is contained within the panelling.

Mixing eras and cultures for dramatic effect, a Greek antique foot sits on top of an 18th century Chinese lacquer cabinet.

Playing with contrasts, a 17th century table with timber inlay is paired with a 1960s steel chair designed by Steven Sclaroff for Pan Am.

The vignette with a French lamp from the Eighties and a silver Italian vase from the Seventies form an arrangement in front of a black Fontana artwork.

Above a bed custom made for Napoleon in the 19th century is a plastic mould of a well-formed bottom from the Seventies.

A Napoleon III mantelpiece is decorated with a death mask of Napoleon and a steel lamp from the Eighties.

MICHAEL COORENGEL & JEAN-PIERRE CALVAGRAC

THEATRICAL APARTMENT

The journey of making a book, as with any creative project, has its ups and downs. The shoot of a London apartment, belonging to a talented but elusive interior designer, had to be cancelled when the space was flooded while the photographer and stylist were in the air over the Indian Ocean. After some frantic emails, it was replaced by one of the most wonderful chapters in the book. In another instance, an email snafu took us to an unscheduled destination – the Parisian apartment of Michael Coorengel and Jean-Pierre Calvagrac – and while it was not what we were expecting, its rare design pedigree and the welcome of its owners gives it a special place in this book. That ‘sliding doors’ moment when accident becomes opportunity is always a cause for celebration.

How else would we have found that collision of styles where a bed slept in by the Emperor Napoleon (on the 30th and 31st May 1811 to be precise) finds itself paired with a cheeky orange acrylic ‘bottom’ artwork and a Warhol banana cushion? But that is only the beginning. This is an apartment where Sonia Delaunay meets Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Marcel Breuer is in the company of classical Roman busts, and Lucio Fontana has more than a passing acquaintance with Eero Saarinen. Fortunately, both owners are interior designers with a deft hand and a keen eye for these relationships, with Michael acknowledging, ‘While we like to create different mixes, every piece from every room can interact, as they all stem from the same philosophy.’

Fourteen years ago, when the pair were searching for something different, perhaps an Art Deco building or an industrial loft, they found this apartment in the 2nd arrondissement of Paris. Its appeal lay in the charm of its Italian Venetian façade and its generous and flexible labyrinth of rooms. Painted in what they disparagingly call ‘shades of French tearoom’, they set about injecting contrast, colour and an interplay of their wide-ranging collections of furniture, art and objects. ‘For us it is difficult to feel restricted by period or genres,’ says Jean-Pierre. ‘We can equally be fascinated by Arts and Crafts pieces, as much as by Danish design, Italians such as Gio Ponti and classical antiques. The convergence of different influences is what we really enjoy.’

Yet it was not always quite this way. Both admit to the creative influence of one on the other, and how it opened their eyes to new perspectives. Their backgrounds have as much in common as they have differences, but in each case the aesthetic pendulum swung in the opposite direction to their family life. It would take a whole book to describe the story of Michael’s ancestry which, for ease, he boils down to Dutch/Indonesian. His parents were glamorous tennis players living the society expat life in New Guinea before moving back to Holland in the Sixties, where Michael was born and their enduring passion for tennis flourished. As a child, the bookish Michael was dragged from event to event. ‘I wanted to draw and read and be taken to museums, and saw no point in chasing a ball around,’ he says. The family home was modern, his mother favouring the Scandinavian greats, with furniture by Arne Jacobsen, which Michael, from the age of five, took pleasure in rearranging when his parents were out. Ill-suited to the study of law, his original area of academic pursuit, he felt much more engaged with history of art. Jean-Pierre made the same educational transition, but coming from a chateau in Bourgogne where antiques formed the backdrop to his childhood (‘Often they were uncomfortable,’ he says), his inclination was decidedly modernist, drawn to the Bauhaus movement and the work of American architect and furniture designer Richard Neutra.

In the silver room, a fur-draped Mallet-Stevens chair sits beside a silk velvet sofa by Jansen and Breuer Wassily chairs re-upholstered in green duchess satin.

Philippe of Orléans’ hand gesture is echoed in the plaster hand next to the Seventies Italian lamp.

In the grey salon, a gilded stylised statue from 1930 stands alongside marble sculptures by French artist Émile Gilioli and a Hutschenreuther lamp.

Once Michael discovered that there was such a thing as a career in interior design, things went into fast forward; he had a period with a formidable antique dealer working with the royals and the uber-wealthy in Holland; he worked with pioneering Belgian decorator Axel Vervoordt, who bought and restored a 12th century castle, Kasteel van ‘s-Gravenwezel, north-east of Antwerp, and gave the world an interpretation of wabi sabi which mixed the weathered with the rarefied. A subsequent introduction to Ralph Lauren led Michael to a job in Paris to launch the interior design arm of Lauren’s lifestyle concept, selling the world his vision of old money through wallpapers and leather club chairs. And yet, Michael’s most commercially successful project came unexpectedly from a client who was a baker with an ambition to have a franchise brand. After redoing the interior of his house in northern France, Michael set about creating the branding for Boulangeries Paul – which has become one of the biggest bakery chains in the world. With the newly minted job title ‘artistic director’, Michael also took on the task of doing the same for Ladurée, the famous Parisian pâtisserie, designing packaging that appeared archival while speaking to a new fashionable audience.

In 1996, he and Jean-Pierre started to collaborate on interior projects, and have done so ever since. Perhaps their greatest joint venture is the apartment they share as they have no client to please – only each other. ‘Alone you often don’t even see how things can become repetitive, but having another person as a sounding board with a counterpoint position can be a challenge, which in turn helps the aesthetic to grow in a positive way,’ says Jean-Pierre.

Working into the existing reception rooms, some elements were heightened and others were left alone to retain what Jean-Pierre terms ‘the manifest from the past’. There is a sense of theatre from the outset – the entrance to the apartment is fitted with a curved track from which muted gold velvet drapes hang to create an enveloping circular space. The rare and intricate plaster mouldings have been highlighted in traditional gold in one reception room and, in a highly unusual treatment, silver in another. ‘We felt the silver had a better connection with the metal in some of the furniture and decorative pieces,’ says Michael.

While the restoration of the mouldings required lengthy, painstaking work, they decided to leave the fragile ceiling frescoes of Boucher-coloured skies and cherubs untouched to retain the patina.

While all appears artfully haphazard, a series of strong stylistic principles are at play. In the silver room, the green duchess satin of the Breuer Wassily chairs is picked up and echoed in the cushions, the lampshade and the tubular-frame of the chair by Robert Mallet-Stevens. The antique rust sofa is tonally compatible, while the freeform rugs in pale grey introduce a lightness of touch and humour. A hanging polished ‘disco’ ball is but one of a number of spheres, in lamp bases, objets d’art and a convex mirror, that become a recurring motif, bringing a thread of subtle continuity to the space. ‘You find these references in classical Dutch paintings and they represent a vision of infinity and reflect different aspects of the room and add another layer of interest,’ says Jean-Pierre.

They both enjoy the idea of moments of ‘cultural shock’ when a discordant combination suddenly sings, and there is also a sense of fun that robs the interior of any hint of pomposity. A piece of heavy wooden antique furniture, from Jean-Pierre’s family chateau, is thrown off kilter by pairing it with a 20th century Italian chair or a Lucite table.

As an interior design duo, Coorengel-Calvagrac are driven by the architecture, the volume and the clients, and are at pains not to have a signature, not to impose their ego on any scheme. They also see great value in retention of what exists as much as newly sourced pieces, and Jean-Pierre tells of a client with an impressive collection of Secession furniture of which he had grown tired. ‘It made us depressed that he no longer saw the value in it, and we worked to find a way for him to appreciate it again,’ he says. ‘When the client saw it in a new light, it carried a great emotional charge for him, which was very satisfying for us. Sometimes you have to be a psychologist.’

An early Sonia Delaunay painting is compatible with the grey context. The 16th century French cupboard and Mackintosh chair are juxtaposed for effect.

The 18th century sofa, once in Marie Antoinette’s Le Petit Trianon, is adjacent to a wooden seat designed by Coorengel-Calvagrac. The order imposed by the panelling is offset by the raw nature of the Nakashima table and the cowhide rugs.