HE FINAL ARGUMENT: THE HAPPY ENDING. So the day of the final argument is here. Now it’s time to close the deal with the jury. It’s time for the salesman to push the order pad over for his customer’s signature. The final pitch is about to be made to the committee. Our story has been told. But the story’s ending will be written by others, by the power persons.

This is our last chance. If we haven’t made the sale to the jury, the customer, or the council by this time, if the boss hasn’t been convinced by our presentation, is it too late? If our story in the opening wasn’t compelling, if the jury, customer, or the council weren’t made to care, if our opening statement was proven false in substantial ways, if we held back the truth and now, after all of the evidence is in, the jury has discovered that we have betrayed them, we can do little to save our case.

If on the other hand we have been genuinely who we are, if we have been connected to our case, cared about it, cared about our clients and ourselves, if we have laid it all down every day, day after day in the courtroom, and our caring has become contagious, so that the jury cares as well, we are ready, indeed. We have earned the right to make our closing argument. But haven’t we already won the case?

I have said that the power persons will write the ending to our story. Our story can end as a tragedy. Or it can end in joy, in fulfillment, in justice. But how the story ends will depend on how we have told it. The only cases that can be won in the final argument are those that have not been previously lost. On the other hand a good case can be lost in those fatal, final moments.

What is the final argument? The morning news of the world’s turmoil fades into insignificance, compared to our concern for our client who sits next to us. We can hear him breathing. We see his face, drawn and pale. He has visited hell. His eyes are blank. He doesn’t speak, the words stuck somewhere in the unyielding pain of fear. We reach over and touch his hand. His life is in our hands. The final argument, our last chance at justice, is on us. The judge nods in our direction, indicating it is our turn to speak to the jury. Will they reject us, turn their heads from us, shut their hearts against us? Our minds are blank, white. No thoughts can penetrate the wall of fear that surrounds us. We walk toward the jury. Our feet feel heavy. We know the jurors’ eyes are peering, the jurors waiting, waiting. Yet we cannot see them. They are blurred objects sitting in chairs in front of us. They stare. We try to smile, but the smile will not come. If only we could run. But it would be more painful, more frightening to run than to stand and fight.

The final argument is a fight. It’s more. It’s the climax of the war in which we’ve been engaged. We have asked the jury to trust us. But we must also trust ourselves. We stare down at the floor, at our feet. We turn inward for our power. Is it there? Has it forsaken us? Will the words come? We feel a sense of helplessness. We try to locate the fear. Where is it? Yes, there it is—around the ribs, under the ribs, its center where the ribs converge. It has taken but a moment, this centering, this becoming the self. At the moment we are nothing but a bundle of fear tied up neatly, our guts around it. We take a deep breath and look up at the jury. Then we hear our own voice:

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury.” There is a long pause as we look at each juror in their eyes. Each of them, juror by juror, and thereby acknowledge them, confirm for them that they are individuals who count. Our eyes say it as they linger on theirs, linger a millisecond longer, long enough that our eyes say we see you, you have trusted us and we trust you also. No one on the jury has been by-passed. No one forgotten.

Then we hear the first words of our argument slipping out. The words are the truth.

I think about what I have just said. It is the truth. Then I say my thoughts. “It is the truth. If it were otherwise it would mean I don’t care.

“Why am I afraid?” Why?”This is the most important time of the trial. Your decision will be the story’s ending. And I pray for a happy ending. I wonder if I have done my job well enough. It is too late to turn back. I’ve made mistakes that I wish I could correct. If I had it to do over again, I would be more kind to Mr. Henderson (the opposing counsel), who I know is only doing his job. I would have listened more closely to his honor who was only attempting to see that the parties have a fair trial. If I had it to do over again I would have done a better job in presenting our case. There were many questions I failed to ask. And I am afraid that I have not done a good enough job. When I think of it I feel panic rising up. Yet, that is in the past, and we can’t go back.

“On the other hand, I am eager to talk to you, for this special time with you. I have been waiting for over two years for someone to hear this case. Mr. Henderson would not hear me. He only filed motions to keep me from getting here. His clients would not listen to me. They turned a deaf ear to George (our client). No one has listened, except, thank God, you have listened. George and I have waited these long years to be heard, and here we finally are, and I am eager to make these last statements to you, because you are the only persons in the world who will hear us and who can finally give us justice.”

Suddenly, I have the sense that the door to my final argument has been opened, and out of it, as if by magic, my argument begins to unfold. It begins to present itself. It will be a symphony, again a presentation essentially in three movements, the beginning, the middle, and the end. Like the music of the symphony itself, it will have harmony, rhythm, and texture. It will rise to a crescendo and fall to a whisper. It will not be contrived. It will be the product of unleashed, genuine feelings. It will not be feigned. No room exists for artifice. Rhetoric is out, there is no room for it. The heart cannot get itself around pretense. It is too taken up with the real.

Every space in the heart where the argument is stored has been marinated with urgent feelings. We stand on these two solid feet and decry the wrongs that have been forced upon our client. What is the final argument? It is the time when, with a sense of ethical anger, with a justified righteous indignation, we ask the jury for justice.

The guide through the forest. I have spoken of the guide—the concept applies to all salespersons, to trial lawyers and laypersons alike. We are all salespersons and, as such, we are also guides. I compare our role to that of Kit Carson or Daniel Boone—someone who knows the territory, and whom the jury trusts. That they trust you! What a responsibility! That they will follow you! What an honor! How humbling must that be! There was another guide they could have followed. There’s somebody over there who is called the prosecutor in a criminal case, and the defense attorney in a civil case. Each wants to be the guide. But we are the guide they have chosen. They’ve chosen us not because we are big or beautiful or strong or articulate. They don’t choose guides based upon the sound of their voices. They choose a guide they trust.

The jury’s guide comes in every size and kind. If we can dig deep into the mother lode of who we are, then deeper still, if we can become even more real, if we can shed all of the masks, if we can always be painfully honest we will become the guide the jury follows.

Preparing the final argument. The final argument, as with every element of the trial, will be fully prepared. As always, we are filling our computer brain with the materials and their organization. The argument has become a part of us. Indeed, we are the argument.

We began to understand the theory of our case as we prepared our opening statement. We developed a theme. We have lived the case. We have wrestled with the demons that visit us as we sleep, and have made our argument a hundred times.

I begin to prepare the final argument the day I get the case. Many a time I’ve found myself sitting up in bed at night before I turn off the lights. I am making notes of ideas, of phrases that come to me. I write out whole paragraphs I think will someday be said to the jury. I keep a file by the bed that I have labeled, “Final Argument.” Sometimes I am visited by a powerful metaphor, or a compelling phrase will come to mind that awakens me—usually in that faint unconscious zone between sleep and waking, in the early morning—and I will write the epiphany down before it escapes.

Recently I was asked to consider the defense of a young man who was charged with the murder of his mother and of a child who was his niece. Days before the murder this young man had displayed irrefutable evidence of psychosis, was delusional, and obviously medically insane. His mother had him hospitalized, and he was examined for a few days. The doctors and other attendants recorded his mental aberrations that clearly showed he was suffering from a severe psychosis. But the hospital personnel released him (he had no insurance), and within hours he returned to his home and bludgeoned his mother and his niece to death. He was committed to a state hospital because he was unable to aid in his own defense. He was there for many months, and finally, on medication, returned to jail to await trial. The state had asked for his life.

As I heard the facts of this case I immediately began creating the final argument. I had a paper napkin in front of me and began jotting notes: Here the villain will be the state itself. The question is, should the state be permitted to cover its own wrongdoing, its criminal release of this man, by now killing him? Should the state be permitted to kill to cover its own mistakes? How can the state seek death, when the state itself caused it?

Under any theory of justice the state should be charged. But because the state cannot be dragged into the criminal court and charged with murder, should it be allowed to kill the victim, the young man who, insane, was knowingly turned loose on the people and converted into a murderer? The state is the villain. The young man is the victim. The heroes in this case will be the jurors who will surely see the injustice of the state’s demand for the life of this man. Surely the jury will see that he should be treated for his illness and confined for life in a state hospital. But from the state’s perspective, so long as he remains alive he is a living reminder, year after year, of the state’s failure to protect its citizens.

The point I hope to make is that when I first hear of a case the facts immediately begin to form the final argument—what is the justice in the case? Who is the villain? The hero? How can the facts be argued so as to reach those psychic places that lie tender and waiting in all of us, that, when touched, respond in our own sense of justice?

I make the final argument in the shower in the morning. While I drive across the land on business I will find myself addressing an imagined jury. During the trial the final argument file is with me at council table. I will slip in notes as the inspiration comes while I listen to a witness, a statement made by opposing counsel, or a comment by the judge.

The organization of the final argument is made many weeks before the trial. It will be edited and altered and added to, to be sure. But its basic form will have developed as a part of the overall preparation of the case. When I walk into the courtroom, on the first day of trial, I could make my final argument then and there. Between the beginning of the trial and the moment the judge nods to me to begin my final argument, all of the ideas and thoughts that will end up in my argument will have been gathered in my final argument file.

In the same way that I write out my opening, I also write every word of my closing. The argument has become fully embedded in me. Although I will take the notes to the podium, I will rarely refer to them. I have not memorized the argument. Instead, the argument has taken on a life of its own. It will direct me once I begin to speak. I will find myself giving arguments with words and supporting metaphors that I had never thought of—not until the very moment they are delivered to the jury. The argument, if it is unleashed, if it is trusted, will create itself. But it has been built and nourished over many months. It has become like a living creature. Preparation gave it life. Once it has been formed it moves on its own, creates on its own, and finally comes to its own climax and asks for justice with an indomitable power.

Approaching the final argument. The final argument is not a rehashing of evidence. It is not a summary, witness by witness, recounting what each witness has said. True, we will talk about the testimony of some witnesses, both theirs and ours, but what a witness may have said or what an exhibit may have proved are but threads woven into the final argument.

The argument is an argument, the reasoning that supports justice, the creation of the whole aura of Tightness that shines down on our case. But there can be no demand for justice until we ourselves feel the ethical anger, the pain, the loss, the righteous indignation.

If we do not know how it is to be Bill Day, a crippled man, a once healthy, happy worker who is now confined to a wheelchair, who cannot feed himself or go to the bathroom or even brush his teeth, we cannot make a final argument. If we do not know what it is to be June Bailey, the mother of a tiny girl, little Sharon, who was burned severely over most of her tender body as a result of the explosion of a pipeline and then died of her injuries, we can never make a final argument. If we have never been to the prison in which the state wishes to cage our client, never seen how it is to lie down to sleep in a six-foot concrete cell where our head nearly touches the toilet stool, we can never make a final argument. The approach to the final argument is to become the victim, to be the accused, to understand the human issues that demand justice.

We remember: Justice is a feeling. It is born of a need for retribution that comes bursting out of the deepest recesses of the human condition, pain that has been fueled by loss, or fear, or depravation, and that is responded to within the limits of our meager ability to provide it. No amount of money damages can bring back the health of Bill Day. A steamship full of money can never stand for the loss of little Sharon. We can never restore the dignity, the lost peace of mind, and the permanently damaged psyche that those wrongfully charged with crimes experience. We who are charged with the impossible task of obtaining justice do the best we can with limited tools—a money judgment for those who have been injured, a march to freedom out the courtroom door for those who have been wrongfully accused. But this is not complete justice. Complete justice could be realized only if we had the power to take our clients back in time before the injury occurred, if we could erase the mutilation, the psychic damage, and put death aside.

Thoughts behind our arguments for justice. As we know, justice is a myth. It cannot be defined. It most often cannot be delivered. What is justice for one can be injustice for another. Justice is the gift of the most compassionate and wise. Yet it always falls short. The victim’s family, whose member has been murdered, cannot experience justice when the guilty is executed. The involuntary eternal sleep the murderer is provided when he experiences the executioner’s needle cannot assuage the grief of those who have lost their loved ones to the murderer. The state’s murdering the murderer in the false name of justice will likely only intensify their injury.

How do those who have lost their life’s savings at the hands of a corporate thief experience justice when the prosecutors make their plea bargains with the thief—all of which will be of little comfort to the penniless in their old age? The state cannot provide justice to victims.

Most often those who commit crimes are the product of the state’s failure, the sad offspring of poverty and prejudice. How does the state dare attempt to deliver justice for the crimes of a person who, from the moment he was born, was himself unjustly punished? As a child he was as innocent as our own. Yet his very birth was a punishment. His life has been a punishment, because the child was deprived of the simplest human rights—the right to be respected, to be loved, to be protected, the right even to experience minimum shelter and nourishment.

I think of two bassinets side by side in the hospital nursery. Two babies have been born on the same day. One goes home to a family such as ours, one in which he will receive all the love and attention and every advantage we can bestow. He is sent to the best schools and plays all the sports, the doting father at Little League, and all the rest. He engages in all the activities we believe precious children should experience to become healthy, useful citizens.

The other child goes home to a three-story walk-up filled with filth, a half-dozen other dirty children, and a drugged-out mother. He is neglected and often goes hungry, is left alone, and is injured and rejected. He soon learns the worthlessness of human life, and his only visions of success are the drug dealers on the corner. He was born as innocent as our own children. Our children are rewarded in their innocence with the best we could provide. He was punished in his with the worst that could be laid on him. Man commits no worse crime than punishing the innocent.

Let me have my arguments: How dare the state punish those who are the products of the state’s own neglect, its own failures? The state can build more prisons, but it cannot provide decent schools and nurturing, protective environments for its innocent children. Most of the criminals who line the walls of our prisons are the product of a failed system, a system that has cared more about war and profit and the domination of the world than about its innocent babes. But it is the same state that points its long, white, accusatory finger at this once-innocent child, now grown up as the criminal defendant, and demands that he be further punished for his crimes, when the original crime was the state’s. It is difficult to understand the concept of justice when it is injustice that causes too many crimes in the first place, the victims of which now petition the same state to deliver them justice.

But at last we understand. The state is not actually interested in preventing crime, otherwise the state, being fully capable, would take such steps as are necessary to reduce crime by fighting the virulent diseases that cause it—such as poverty and lack of opportunity. We know that the state cannot deliver justice, no matter how many of its miscreant citizens it executes or imprisons. The state punishes the crimes of its people in order to retain an orderly society. An orderly society is necessary for those in power to retain power. If crime is rampant, if the streets are not safe, if those who are the victims of crime personally undertake to avenge the crime, the resulting chaos would threaten those in power to hold on to their power. The United States houses more of its citizens in prison than any other nation in the world. We have more African-American men in prison than in our universities. Can we do better?

I am not in favor of anarchy, nor do I believe that we ought not have a system governed by a rule of law. I believe in the elusive goal of justice and hope for its rendition, as inadequate as it is. But the notion of justice is complex. It demands that we consider it beyond the simplistic idea that Joe shot Harold, and therefore Joe should be locked into the gas chamber and the nozzle turned on. Those who suffer from a disease are not taken out and shot—not in this society. But in a rich society such as ours, much of our crime is a disease, the base cause of which is the simple need of its citizens—nourishment, shelter, education, and an equality of respect and justice.

Seven steps for winning the final argument. I have never been one to rigorously follow rules. I think, instead, that we have a duty to break rules whenever possible without injury to others, because rules most often become a substitute for creativity. Rules are like the paint-by-numbers paintings that were so popular years ago. If people can be taught to follow rules, they need not explore their own unique and perfect potential.

But the expectation of a how-to book is to tell folks how to do it—often step by step. So I wondered as I began to write this chapter, how do I organize the final argument? I proceed, usually in an unconscious way born of many years of experience. Now I’ve tried to bring those steps to the surface of my own consciousness, to consider them step by step, with the hope that they will help you with an approach of your own on how to put together your final argument.

Step 1: Identify the hero and the villain. As we have seen, in every novel and movie, indeed, in every trial the story centers around the conflict between the villain and the hero. In the courtroom we need to identify who occupies these roles. Our client, yes, we, are the good guys and our opponents the scoundrels. Successful lawyers are usually subliminally aware of this dynamic, and both sides instinctively vie for the position of hero. Whoever emerges as the hero will likely be the victor. We do not side with villains. In our final argument, then, we want to cast ourselves in the role of the hero, the humble hero to be sure, the kindly hero who smiles through his tears, who has been courageous, steadfast, and true, and at the same time to cast the other side as the uncaring, greedy, insensitive villain who exercises his power over the weak and the helpless for profit. In the criminal case we are the wrongfully accused, or the grossly misunderstood. We have become a victim ourselves, and the prosecution is callous, cruel, and vindictive.

The jurors may be the heroes. In every case we empower the jurors as heroes and cast them in the role of rescuing champions who refuse to deliver the helpless defendant to the state to imprison or to kill, or who deliver a money-verdict justice to the injured plaintiff against the will of the wrongdoer.

Revisiting the voir dire and opening statement. By now we begin to realize how important the first two segments of the trial are—the voir dire and the opening statement. Justice to a poor family who has been evicted from their home by the bank may be quite different than justice to the banker whose loan to the poor family remains delinquent. As we choose jurors in the voir dire, and later tell our story in the opening, it becomes apparent how critical the selection of jurors can be. We search for persons who will identify their heroes according to the same values we cherish and for persons who define justice as do we. To the banker, justice is the timely payment of the loan he made in good faith. To the poor family, justice is some magical legal reprieve from being cast into homelessness. To jurors sympathetic with the tenets of sound business, justice is the enforcement of a promise, the consequences of which, although sad, were the risks accepted by the borrower at the time of the loan. To jurors who have lain awake at night worrying how they were going to manage their indebtedness, any rationalization to prevent the bank’s foreclosure will serve justice. As we have seen, that which is justice to one is often injustice to another.

We do not attach ourselves to heroes we do not trust. Oftentimes one of the lawyers becomes the hero—the other lawyer the villain. I have discussed the notion that jurors tend to identify one of the lawyers as their guide through the forest of litigation. And as the trial proceeds, the parties themselves often recede into the background and the attorneys become the focus. We see this when a corporation is represented in the courtroom. The lawyer tends to become the corporate entity. He speaks saying, “We are so sorry for the injuries the plaintiff has suffered” (though the corporation cannot feel), and he goes on speaking in the first person plural, to the end that the jurors, even the judge, begin to see the corporation as Mr. Heartfelt, the corporate lawyer.

In both civil and criminal cases the parties in the trial begin to fade away, because for days only the lawyers may be heard from, while their clients for the most part remain silent. Day after day, as the lawyers argue and question the witnesses, the lawyers gradually become the litigants, so that, as I have so often emphasized, the credibility of the lawyer is all he has—and, at last, all the client will also have. In the courtroom we may encounter the most honest client who ever drew breath, but if his lawyer has lost his credibility, so, too, the client will be seen as a bird of the same feather.

In sum, before we can make the final argument we must identify the parties, the heroes, the villain—there may be more than one of each. But there will always be the star, and there will likely be the one who is principally responsible for the injuries or the failure of justice—the villain.

Step 2: Become the victim. We know we cannot make the final argument without having become the victim. It’s only when we’ve felt the injuries and the pain of the injured that we can begin to understand the stakes. Often the victim may be more than one person. In a civil case for personal injuries, the victim may not only be the child who has been injured at birth by a careless doctor, but the parents of the child are victims as well. Their burden will be to care for the child for the rest of their lives.

The victims in a wrongful-death case are not only the deceased but the surviving heirs, the husband or wife, the orphaned children, or the parents who have lost their child. In the criminal case the victims may occupy both sides of the case. In a murder case the victims include both the murdered as well as his family. But what about the family of an accused who will be put to death or imprisoned for long periods of time? The murderer’s family is often as innocent as the heirs of the person he killed.

What justice for the victim? To understand the life of the victim, we must understand what justice is available to the victim. In judgments against the negligent corporation that bestows death or injury on innocent citizens, that corporation will only be made to pay money out of its coffers. In the criminal case punishment is often seen as justice. Punishment, of course, implies that the person punished will be taught something. We justly punish a child for his wrongdoing, hoping that the child will reform. We dock a worker his pay for his misadventures on the job, hoping that he will not repeat them. But I have never been able to understand how we can teach a corporation much, unless, of course, it is required to give enough of its green blood to cause its management (the members of which are usually immune from punishment) to take notice of its diminishing bottom line. And how, pray tell, do we teach the murderer not to murder by murdering him ourselves through the executioner’s needle?

In the civil case justice will be the money it takes to provide the necessities the victim will require, and to pay in dollars for the pain and suffering he has endured. Still, the equation is never balanced. Would we rather be a man sitting for the rest of his life in a wheelchair with ten million dollars in the bank for his loss of enjoyment of life, or a healthy man who is so poor he must sleep under the bridge? Justice always comes up short. And no matter how many murderers we kill, we know that their moldering in the prison cemetery will not bring back the victim’s loved one. Yet victims are entitled to the best justice that the system can offer. When the system falls short, not only does it fail its citizens, it also exposes itself to its eventual demise.

What about the injured person, say, the mother, whose child was killed by a negligent driver who was insured and is now being defended by the insurance company? Call the driver Blatty. Preparatory for our final argument let us walk in the mother’s shoes. We have done a psychodrama and we have become the mother. As someone said, the longest journey we will ever take is from the mind to the heart.

To this mother, this strange process called a trial is like walking into a bad dream where the people in the room speak a foreign language, where they seem oblivious to her, this person who quietly sits at counsel table slowly disintegrating internally.

She has been admonished by her lawyers to say nothing and never to cry out. She struggles with a nightmarish potpourri of grief and anger and a sense of helplessness. The attorneys are arguing over things that make no sense to her, about other cases, rules, and evidence. And some of the witnesses are lying. Her own lawyer seems unconcerned about her misery and the insanity of the whole draconian drama unfolding in front of her. People are screaming and pointing their fingers at her and each other, the judge is pounding his gavel, and all she wants to do is to run out of the place. This is justice? No. It is a trial.

This mother, this plaintiff, as she is called, senses that she is being used. Without her there could be no trial. Without her, her lawyer could make no fee. Without her, the defense attorneys would likely be in ragged suits bulging at the knees, instead of their sleek, well-pressed designer clothes that cost more than the old jalopy she was driving when the drunk, Blatty, ran across the road and killed her daughter. What is there to argue about? Yes, she is being used. They do not care about her—not deeply. They care about the money, about their reputations, about winning. They have their personal agendas. They seem barely aware that she is in the courtroom.

No one has spoken to her for most of the day. The judge has never looked at her. The witnesses do not talk to her but to the lawyers. The jurors look at her from time to time with dark, skeptical faces, as if they believe she is there only to enrich herself. She is embarrassed when they look at her. They must think she is an evil hussy who wants money for a dead daughter. They are right. How can she ask for money for her dead child? It denigrates her child and reduces her to a money-grubbing bitch who would turn her dead child into dollars.

But she had gone this far. She couldn’t let Blatty get away with killing Polly and pay nothing. She wanted him to pay, to go to jail, to suffer as she has suffered, but her lawyer said that the guy was insured by a national insurance company and that he would never have to pay a penny of his own money. Somehow the cops forgot to take a blood-alcohol. The driver claimed he had drifted off to sleep momentarily. Swore he wasn’t drunk. And her own lawyer said the defendant would never be charged with anything worse than negligent homicide.

She wept for months. Once she beat at the walls in frustration. Her husband felt grief too, but not like hers. No, he was tough and he tried to comfort her, but no one knows what it’s like to be a mother who has lost her child, except a mother who has lost her child.

They sent her to grief counseling, and she learned it was all right to have her feelings, to be angry and hurt, and to experience those feelings of helplessness. For months she was unable to sleep. She lost her appetite. Her husband said she was wasting away and that she had to straighten up and face the loss. In the meantime she was told that her neighbor recently saw the guy who killed her daughter, that Blatty, at the bowling alley drinking beer and having a good time.

She and her lawyer were in and out of court for nearly two years with all the experts’ depositions and the motions filed by the insurance company. The insurance company lawyer tried to beat her lawyer with a bunch of technical garbage that made no sense to her. The insurance company attorney, a smiling prig, asked her a lot of questions when he took her deposition. He made her cry and then pretended he was sorry. He wanted to know how much money she wanted for her dead Polly and her lawyer told her not to answer. She felt like some sort of money-sucking Dracula, and his questions weren’t fair. He tried to make her look like she didn’t remember, or that she was on his client’s side of the road, or that she could have avoided the accident—that it was her fault! Her fault that little Polly was dead! He tried to make her feel guilty.

Her lawyer said she hadn’t handled it very well in her deposition. She knew she didn’t. She cried, and then she hollered at the insurance company lawyer—said he was trying to make a liar out of her. She was ashamed of herself afterward. Her lawyer said that if she did that on the stand in the trial she would lose the case for them.

As she sat in the courtroom she was afraid. What if she couldn’t control her anger? What if she broke down crying in a public courtroom? Blatty was staring at her. She couldn’t bear to look at him. She couldn’t look at the jury. She didn’t know how to look. Pretty soon her lawyer would be calling her to the stand and she would be required to testify about the accident, and about little Polly. She wished her husband were there, but he had to work. They had bills. Funeral bills. Hospital bills for her and Polly before she died. And since the accident—it wasn’t an accident, but everybody called it an accident, even her own lawyer—since the accident she had been unable to work and had quit her job. They needed the money.

Yes, just before trial the insurance company offered them a settlement—her lawyer said a hundred thousand dollars. Then the judge ordered that everyone get together in a mediation and try to work it out. She had gone, and the defendant was there along with that smiley insurance company lawyer, and all that happened was that the company offered another hundred thousand dollars, total of two, which just made her own lawyer mad. He said it was pathetic—that they were trying to get away with another murder. They had already killed little Polly, he said, and now they wanted to sneak out of the case for a measly couple hundred thousand, when the case was worth a couple of million. He pointed out to her all of the cases around the country where little girls were bringing two million and over. They were trying to cheapen Polly.

She went home and talked about it with her husband and he said they should leave it to their lawyer to decide. He knew more about this than they did. She cried a lot more and couldn’t sleep, she kept hearing her lawyer say that little girls were worth a couple of million—like the price of a racehorse or something, as if her little Polly was a thing that could be bought and sold on the auction block. She wanted justice. She wanted Blatty to pay. She wanted someone to feel like she felt, lost, drowning in grief, helpless, lost. She felt like her life was over, and that the only justice she would ever get would be the insults they were throwing at her in court, the lies in that awful place, the coldness of an impersonal law that never knew her, never knew her husband, never knew little Polly, and never had the slightest desire to do so.

Not once had the judge even smiled at her. The court officials, the clerk, the court reporter, and the bailiff never spoke to her. The jurors passed her in the hallway and never even nodded in her direction, never looked at her.

Now she was called to the witness stand. She had worn her black dress, the one she wore to bury her mother, and then little Polly. She put on no makeup because her lawyer said she shouldn’t look too pretty, even if she was pretty. She never believed him when he said that. She hadn’t been pretty a day since Polly died. She walked to the stand on her low-heeled black shoes and tried to settle into the chair and look right and proper. People were staring at her, she knew that. They were going to judge her now, to come to a conclusion as to what kind of a woman she is, what kind of a mother she’d been, whether she lied, whether she had caused Polly’s death, whether she was just trying to take advantage of a tragic situation for a bunch of rotten money. But her lawyer told her that money was all the justice she could get. Just cold, dead money, she thought, for a cold, dead child—that’s all the law provided.

And she knew the lawyer was going to ask her a lot of questions about little Polly, what she did, how they laughed with each other and played together—actually played together like little children. She would have to share the most intimate things with this jury, with utter strangers, about their relationship, the prayers they said at night, the things little Polly wanted to be when she grew up, the secret ambitions she had for her child—maybe to be a great scientist or a doctor, or someone who could make the world better—a teacher maybe. Yes, maybe a teacher.

Little Polly was bright as new pennies. The teachers said she was a very smart and lovely child. And she thought about God. If there was a God, a loving God, why had the child been taken from her? What sins had she committed, what wrong so terrible that she should suffer this loss? At times she had wanted to die, when she had thought about taking all of the pills the doctor had given her. What was the use? She had been put on this earth as a mother. Her child had been taken from her. Perhaps, in God’s eyes she didn’t deserve to live. Perhaps if she died she could be with little Polly again and they would be happy forever. She mentioned that once to her husband and the next thing she knew her lawyer and her husband had her in the office of a shrink who thought he knew all about what she was going through.

Now, on the stand, her lawyer would drag her through the whole horror again. Yes, she had to tell the jury. She was the only one who could. She had to tell them how it happened. She had to do it for Polly. And worse, she had to tell them what she saw when the crash was over—how she saw the blood covering the child’s face and her long blonde locks soaked in it. She had tried to get the child out of the car, but her own leg was broken and her ribs as well. She reached over for the child and all she could do was scream. She couldn’t move and her baby was breathing mouthfuls of blood that came out in terrible bubbles. Then she passed out and didn’t remember anything after that until she came to in the hospital. Her husband was there, and the first thing she asked was how is little Polly, and her husband just looked down at his hands and didn’t answer her.

She also doesn’t remember much about what she said on the witness stand. It was as if she were a talking mannequin and that what she said was in a foreign language that no one understood. She remembered the insurance lawyer, still smiling, asking her questions. She answered them as truthfully as she could. She was crying sometimes. She was unable to understand what the catch was in some of his questions, little nuances that she knew must be there but that she couldn’t decipher under the pressure. She never looked at the jury. She couldn’t. Her husband would never cry like this.

Then she had to listen to the lies of the so-called experts for the insurance company who tried to make it look like she was on the wrong side of the road. Then Blatty got up and lied, and she saw one of the jurors nodding as if he believed him. The next day the judge read a bunch of legal stuff to the jury, and after that the lawyers got up and argued the case. Her lawyer was first.

Before we can argue effectively we must become the mother, to join her at the heart level. It takes skill and caring to get there. How must it be to lose the child, to have people blame you, to have people suggest there is shame in suing for money for a dead baby, to have to relive the horror of your child’s violent, bloody death? This is the stuff the jury must hear from the mother’s lawyer who has tried to live this case with her. And the jury will also hear the lawyer’s own frustration—that the law of mere mortals can do nothing more than award money to these grieving parents. That’s all the justice there is.

In a way, it has become an unholy war between devastated parents and the insurance company. A fund exists. The insurance company calls it “a reserve” set aside for this case. The fund is supposed to represent Polly’s life, the reserve the insurance company clings to so desperately as if its own nonlife depended on it. If Polly’s parents decide not to go to court the insurance company would simply keep its profit—profit over the death of their child.

In the courtroom the parents’ lawyer will never be permitted to mention that the defendant was insured. The jury may believe Blatty is represented by the lawyer he hired out of his own pocket and that he is only a working stiff, as are most of the members of the jury. It’s the unfortunate law in every state in the union that insurance can never be mentioned—a lie the law foists on the jury. The insurance companies enjoy better laws than the people. But that’s another issue.

By employing the methods we have taught here we have become the mother, the victim. We have felt how it must feel to be the victim. And that experience becomes a part of our final argument. Perhaps some of it will be delivered in the first person, as if the lawyer is little Polly’s mother. I can hear that part of the argument as it begins:

“Ladies and gentlemen: This is a mother who has lost her child. (The lawyer stands behind the seated mother with his hands on her shoulders.) What is that loss? Is it money? It is a search for justice, for all of the justice the law can give. How does it feel to be seated here, your child in the grave, the jurors looking at you, the smiling Mr. Heartfelt questioning you, suggesting you caused your own daughter’s death, when you and everyone, even Mr. Heartfelt, know that that is a lie, a horrible lie? If this mother could speak her feelings at this moment we would hear her say, ‘I have had to relive the hell of this case all over again. I had to see little Polly’s happy face turn to blood. I have had to relive being trapped in that automobile. I am there right now. I am screaming, trying to get the door open….“’ And the rest of her story, as we have experienced it together, will come out in the final argument in the first person so that the jury, too, will relive it.

In the criminal case. Let us remember: The human emotions that are felt by the victims in a criminal case, say, the feelings of a mother whose child has been abducted and murdered, or the feelings of a woman who has been assaulted and raped, are not substantially different from those felt by Polly’s mother. The need for vengeance, for retribution, for justice are part of the human composition. But we are defending the alleged criminal—that is to say, we are there to see that the defendant gets a fair trial and that his rights are preserved. Why do we want to know anything about the victim in the criminal case?

Each of the jurors has likely been a victim of some crime—a break-in, a theft, an assault. Jurors are afraid of criminals, and the most expeditious way of protecting themselves as potential victims is to do away with the accused, guilty or innocent, by seeing him to the gates of the penitentiary as quickly as possible. So we must become the jurors, the surrogate victims in any criminal case.

Employing the methods we have learned here by reversing roles with the victims, our argument to the jurors on behalf of an innocent client might sound like this:

“I cannot tell you, nor can we ever fully feel the pain of having a loved one murdered. It leaves a scar so deep and so intractable that it will never heal, not if Mr. and Mrs. Schoolcroft live a hundred years. The horror of having a loved one taken from us by the hands of a fiend is something we cannot understand. There is no pure time to grieve, because our grief is overlaid with shock and anger and a need for justice. A part of us wants to kill back. But we cannot. And we would not.

“We cannot sleep without seeing the face of our murdered child asking why this has happened to her. We cannot go about our business, because everything we see or touch reminds us of her. We cannot turn on the television, because our case is being discussed publicly as if it is some kind of spectacle to entertain the viewers. We are ripped apart with our emotions. There is no place to go, to hide, to relieve ourselves of the sight, the horror.

“But there is another victim here, and that’s Jimmy, the defendant. He is charged with this horrible crime. It is a crime that the evidence shows he did not commit. We have all been made victims here, you, the jurors, who have been victimized by the state’s false charges against Jimmy, the Schoolcrofts by the horrible loss of their beloved child, and Jimmy by being charged with a crime he did not commit because the state failed to do its job honestly, fully, and competently. The state wants to solve this case and to close its files as do we. But we cannot let them do so by victimizing all of us, including the Schoolcrofts who would be the first to object with all of their hearts if they knew that the state’s files should be closed by the persecution of an innocent man.”

This argument might continue with living a day in the life of Jimmy, who has been confined in jail for seventeen months awaiting trial. It will recount his own horror (that can be fairly inferred from the facts) at being charged with a crime he did not commit. The argument will discuss his terror at being confined for the rest of his life, or even executed, when he is innocent, and his sense of helplessness. (Many states do not permit lawyers to argue the punishment that awaits a person found guilty of the charge brought against him. But jurors know, and the issue can be approached in a general way so that the specifics of the punishment are not set out.) We have tried to live the client’s case, to understand his fear. And part of the argument in that regard might sound like this:

“How would it be to go to sleep at night on a dirty, hard mattress in a steel box called a cell and dream of the executioner’s needle and to awaken in a cold sweat knowing that it is not just a dream, that it is the reality awaiting him if he is not able to convince a jury of his innocence?” Perhaps there will be objections here. Strangely, in many states the law does not want jurors to consider the consequences of their decision. The same law demands that we fully consider the consequences of our acts, failing which we may be held responsible by the law.

Step 3: Feel the righteous indignation, the ethical anger that motivates us. We have traveled to a painful place, to the heart place of our clients. How we got there may depend on who we are and what resources we have. Perhaps we have arrived there through days of attending to our client, from hours of listening. Out of our listening skill we will be able to hear not only what little Polly’s mother has said, but what she has not said, what she is afraid to say, what she has blocked from her mind in order to simply survive another day. We have reversed roles with her. By these methods we have grown to understand her, and she us. We have said to the mother, “Let me be you for a moment. I see Blatty’s car coming at me. What do I feel? What do I say? What do I hear?”

If we are the Schoolcrofts, the victims in the criminal case, we feel the same, a grief that is also stained blood red with anger. If we are Jimmy and we are innocent, we feel fear first, and then anger and frustration that we cannot escape from this trap. A fog of justice denied, of righteous indignation covers all of our feelings. It is an ethical anger. And our anger is the fuel of our passion for justice that moves the final argument, that forms the tone of the argument, that touches and energizes us in our delivery. We can be gentle, if it is appropriate. But let us think of this energy as the empowering anger of justice. We will not lose our sense of reason, but justice, at last, demands retribution. Our need for justice will become the theme of the argument and will set its tone; and having felt it, it will erupt in an argument that will connect to the jurors’ native need for justice as well.

Step 4: Determine the justice you want. In little Polly’s case the final argument might sound as follows.

“We know we cannot get justice. The only justice the law offers for little Polly’s parents is a fund of money. It sits over there on the desk of Mr. Heartfelt. Imagine it as a large box. (I might pick up a cardboard box and take it over to the defense table and set it there.) Imagine that this box is filled with bills of a large denomination. In the law it is the fund that represents the life of Polly. How much is in the box? You will have to tell us. I would suppose the box contains five million dollars. Perhaps more. Perhaps ten. You will decide. This is how I imagine the justice in this case—sadly, the only justice there is. But Mr. Heartfelt’s clients want to keep all that’s in the box.

“What are little Polly’s parents to do here? Their child has been killed by Mr. Blatty over there, this child who was suddenly smashed so that what seconds before was a beautiful, happy child is converted into blood and horror and death. Mr. Blatty was drunk. The evidence is clear on that. He doesn’t even try to deny it because he can’t—he’s a drunk driver who ran his car onto the wrong side of the road and killed a little girl. Had he done it with a club, we would call it murder. But he has done it with something thousands of times more deadly than a club—a car that weighs more than a ton and becomes a steel club traveling at eighty miles an hour, the force of which is nearly incalculable. He was the killer. His car was the weapon. Yet the only justice we can ask for here is what’s in the box. No one goes to jail in this case. Why? Well, his honor says we cannot go into that.

“The law is so helpless. It cannot bring little Polly back, not even for five minutes. If it could, her parents would say to the defense, “Keep the box. Keep all of the money in the box. Keep it all! Just give us back little Polly for five more minutes! One smile from her, the feel of her arms around the neck of her daddy, her cheek against her mother for five minutes—but the law is helpless to provide little Polly for even five minutes. It can only give money.

“So what are Polly’s parents to do? Should they say, well, Mr. Blatty, since the law cannot give us back little Polly, not even for five minutes—since there is no adequate justice here, well, just keep the box. Keep the money that stands for Polly. You want it so badly. Well keep it. Should they say that? Should they permit Mr. Blatty to not only kill their daughter but to be enriched by keeping the fund that is in the box? Are they not entitled to receive the best justice the law can provide, even if it so piteously inadequate?

“And the guilt here! Ah, yes, the guilt! How can parents take money for a dead child? That is the guilt that is laid on Polly’s parents. You’ll not hear Mr. Heartfelt say so in so many words, but he will likely remind you that these parents are here to get money, as if what they are about is shameful. But he will not say that it is wrong for the defense, for Mr. Blatty’s side of the case, to keep that money. How do parents feel who have lost their child, to take money in place of their child when there is no other justice but a fund of money? They feel guilty. But should they?

“I have not heard Mr. Blatty even say he was sorry. Not a single whispered word. Not a bowed head. Not a tear of remorse in his eye. Just the smirk, the arrogant swagger. This man has done nothing but desperately clutch onto that box of money by launching the defense he has in this case—a false defense that he knows is false.

“I feel sorry for him. He must hurt terribly inside, the killer of an innocent child. It must be hard for him to face it. It must be hard for him to look over at Polly’s parents and to say what he has said. He must be a very miserable man, to have first killed and then tried to cover it up with his denials and with the expert he has hired in this case to undermine the testimony of the patrolman. I am sorry for you, Mr. Blatty, and I have no hatred against you. Only sadness that you could not walk into this courtroom and admit what you did. Perhaps you cannot bear to face the truth. I can understand that. The burden of guilt you must bear must be horrible. Yet, in the end, your denial of the facts, yes, even your attempt to cover the facts with the testimony of your expert, Dr. Fix, can be no substitute for the truth, and, in the end, cannot assuage your guilt.

“The defense in this case has not tried to make life better for little Polly’s parents. Instead they have tried to transfer their own guilt for Polly’s death onto her mother, who was driving the family car. The defense has hired an expert here to come into this court, an expert who took an oath, and who tried to show that the patrolman was wrong when he fixed the point of impact clearly in the lane of Polly’s mother. It is one thing for a drunk driver to kill a little girl. But what are decent people to do when the drunk hires the likes of Dr. Fix to come in here and tell you that Polly’s mother lies, that the patrolman lies, that the experts we called are all wrong, and that the truth in this case is the story Dr. Fix, this so-called reconstruction expert, has concocted?

“Justice has many facets. It is not just money. Justice will also be a verdict that tells Polly’s parents that the suffering, the grief, the pain, the inexorable ripping of their very hearts and minds has been understood by this jury. You can turn them out if you want. You have the power. You can say with your verdict, we do not know, nor do we care how it has been to sit in this courtroom and hear the evil mendacities that have been hurled at these parents—the unspeakable transfer of guilt. You can say that you do not care to concern yourself with the pain that comes from seeing one’s child killed in front of one’s eyes, the shock, the horror of it and then have the drunk over there blame the mother for her own child’s death. That is the most despicable assault that one human being can make on another.

“Justice speaks in many ways, and although the verdict here can only be in money, your verdict can say that these parents were heard, that there were other human beings on this jury who understood.

“We are not here asking for sympathy. No one wants sympathy. We want only understanding. We want to know that somewhere out there on the face of this earth are humans who understand the pain, the helplessness, yes, the anger that these parents have endured, endured as decent law-abiding citizens, endured silently, endured without aggression toward the man who killed their child, that they have instead expected the law to do its duty, and that you, as jurors, the spokespersons for the law, will do yours and return the full justice that the law allows.”

We can immediately see that the specific facts of the case have not been repeated. They have been used as reference points in the argument. There may be further facts that should be argued that show that the defendant’s reconstruction expert is wrong, that he is a hired charlatan—whatever the evidence may be in that regard, but always, the facts are but ammunition for the argument and are never to be recounted in the form of witness summaries. But throughout the argument the tone will reflect our sense of ethical anger, and honestly delivered, our argument will infect the jury and create in its members a powerful need to provide justice.

Step 5: Ask the jury to give you the justice you want. We know the old biblical admonition: “Ask, and it shall be given to you.” Whether we are talking about a jury verdict, a sale, or a proposition we present before a board or commission, we must ask for exactly what we want. Remember, when we ask for justice, it transfers the ball into the power persons’ court, in this case, the jury, who must agree to the request, modify it, or deny it. Those who leave justice to the power persons’ whim, who are afraid to ask, have already been defeated. If we do not ask, we will likely not receive. If we are too timid to lay out our prayer for justice, why should the jurors do it for us? Being candid about our expectation of justice is merely a continuation of the policy of honesty we have learned to adopt in our presentation. Lawyers ask me, “How do you get those big verdicts?” I reply, “I ask for the money. I simply ask for it.”

In this case I might say to the jurors, “How much money is enough, here? We can load a freight train full of money and never get little Polly back. The defense knows that. And they will agree wholeheartedly with the argument that since money can do no justice, well, why give any? Yes, sometimes I feel that way too. What is the use? Wouldn’t we all be better off just to let drunks kill our little children than to try to get the only justice that is available to us?

“I think about that a lot. But money speaks. I do not want to bargain for Polly as if she were a car sitting on a cheap used-car lot. I have said the fund in this case is at least five million. It’s in the box over there. I don’t want just a part of little Polly. You could give me half a million for an arm. Another half a million for her smile and her loving eyes. I don’t want justice that stands for just part of her. I want it all. All of the money that stands for her.

“Sometimes I think I have asked for too little. I am afraid and I wish I weren’t so afraid. But I am afraid that people will think that I am taking advantage of a horrible situation here, that people might say, ‘Look at that man, Spence, asking for five million dollars for a dead child. That is vulgar.’

“But the killing, was that vulgar? The most disrespect that can be given to the human race is to kill an innocent child and then claim it is vulgar to seek full damages.

“I think of the world’s most valuable painting, the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci. Its value is hundreds of millions of dollars. But it is merely a painting created by a man on canvas with paint. If some villain came into the Louvre, the museum that houses this painting, and slashed it beyond the ability of anyone to repair it, if they killed the painting so to speak, no one would argue that its full value shouldn’t be recovered from the culprit. But what if someone destroys the perfect work of our creator? Was not Polly the perfect work of God? Should I be embarrassed, yes, even afraid, to ask for a sum that stands reasonably in this society for her? I ask you not for part of Polly. Don’t cut her in half for me. I want all of her. All of her.”

In the criminal case we might argue:

“What do we want here? We want out of this horrible concrete and steel trap where nothing but hatred and vileness grows, where the sound of birds is replaced by the raging of criminals, and the sound of the voices of little children is drowned out by the laughter of the insane and the clanging of steel on steel as the prison doors are slammed shut. We want freedom. We are not interested in part freedom. There is no such thing. A person is either free or not. We do not want part justice. People who get part justice are caged along with the guilty. We do not want to bargain. Jimmy is either innocent or not. We do not want injustice. Injustice will be leaving the smear and the stink of guilt on Jimmy that can only be washed away by your verdict of not guilty.”

Step 6. Create a vision of a better person creating a better tomorrow. By the time we have lived but a few decades we soon realize this is not a perfect world. People cheat. Corporations and politicians, their lackeys, are powerful and in control. People are careless. Government is filled with bureaucrats who exercise their power wrongfully. Prosecutors want power and sometimes persecute the innocent. Greed and profit trump caring. It’s dangerous out there. People’s rights are in jeopardy. Things are not fair. Injustice is rife like the weeds in the lawn. And because we are who we are, most of us suffer a quixotic fixation of doing good and righting wrongs. Were it not so, I should not have written this book and perhaps you would not have read it.

Every case is more than a case. Most judges and jurors are at least subliminally aware of their need to make things better. Most judges will confess that they believed when they took on their robes that they could make their community better by ascending the bench.

It is we who provide the vision of a better tomorrow. It is we who empower the jury and the judge. The sixth step in the final argument is to create a vision of a better tomorrow. Martin Luther King Jr. had his dream. Christ made his promises of a place beyond that he would prepare for his followers. Our founders had their visions of freedom. Today, both Republicans and Democrats have theirs. The talent of a true leader is to create the visions that empower us. Their dreams, their visions of a better time to come become ours. Without such visions the history of the human race would be locked in stagnation. So we must provide a vision for the jury.

But there is perhaps an even more compelling need that hunts us down like hounds on a hare. We have that bothersome need for ourselves to become worthy, to feel the joy and the pride of having done right. Ebenezer Scrooge ultimately listened to his noisy inner voice that also commanded charity. The human race engages in the most abominable of atrocities. It conducts wars against the innocent and destroys the earth for profit, but all of our cruelty and viciousness is for the announced goal of doing good. In the courtroom we will create a vision that will empower the jury to do right, not only for those who follow, but in the fulfillment of the juror’s own need to become worthy. In little Polly’s case we might hear ourselves arguing:

“Factually, little Polly’s case is simple—a drunk runs onto the wrong side of the road, smashes into an oncoming car, and kills an innocent little girl. What do we, as jurors, want to say about this? We have the power. Justice is in our hands—today, and yes, tomorrow in countless other cases of innocent mothers and fathers and children being killed. Do we recognize our power? Do we understand that in a nation whose laws are based on precedent that there will be an endless line of innocent children, yes, innocent people who will look back on this case for guidance? Do we realize that jurors in the future will need the courage that you can provide by your verdict here to bring uncompromised justice to many other innocent little Pollys? Do we understand that our verdict today may save some children in the future by making the killing of innocent human beings so expensive that society itself will take more urgent steps to prevent the placing of such a deadly weapon as an automobile into the hands of a drunk?

“Most of us do not understand our power. We live so vividly in the present we have little understanding as to what the consequences of our acts will be in the future. I think of the founders of our Constitution, who, by their vision, are responsible for our being together today. But for them there would be no jury, no trial of the kind we have experienced. But for them there would not be twelve ordinary citizens deciding what is right and what is wrong. As they met on that hot Philadelphia summer, to sweat and argue in a poorly ventilated place we now call Constitution Hall, do we think that they foresaw us gathered here today? Did they have full understanding of the consequences of their labor, their love for freedom, their passion for justice? It was probably more likely business at hand—the need to act wisely and decisively to establish a new nation. I doubt that they could have understood that a jury would be evaluating the life of little Polly here today.

“So it is with us. We have the power to do right. We have the power to do what is just. We have the power to tell the world that drunks cannot kill our children without paying every uncompromised penny that that child stands for. It is your power. It is a power that will extend into the future to protect the innocent. Rarely do we have the opportunity in our lives to bring about important change and, by doing so, to fulfill our own destinies. Most of us are never given a chance to exercise the God-given power that is vested in each of us. It ought not be wasted. These are such rare opportunities that fate provides the chosen few.”

In the criminal case the vision is of an innocent man walking out of the courtroom free. The argument could be:

“A great American said, ‘I have a dream.’ I have one as well. As the clerk reads your verdict, our hearts will be wildly pounding in our chests and we will be barely able to breathe.

“I dream that after your verdict has been read a great joy will erupt in this courtroom. I have a dream that when your verdict is read an indescribable, nearly godly relief will come over Jimmy and over us. He is free. And in my dream I see us all walking out of this courtroom together as free persons—you, as jurors who have done your duty, who will go home to your families knowing that you have done the right thing, and Jimmy who will walk out of this courtroom with you, also a free man, a man who can go home to his wife and his family, a man who has learned that there is still love in this world—even for a simple man such as Jimmy—and that the greatest proof of such love are two simple words, ‘Not guilty.’

“I have a dream that this great American system of justice still works, and that even the humblest of us, the poorest, those of us who were forgotten both by man and by the law, can achieve justice here within these hallowed walls.”

Step 7. An ending transferring the lawyer’s responsibility for the client to the jury. So you are a juror, and you have heard the final arguments from the plaintiff in the civil case or the defendant in the criminal case. In both the civil and the criminal case there must be a truthful but dramatic ending, one that transfers the responsibility for our client from the lawyer to the jury. This is a story I have told many jurors in both civil and criminal cases as a way of transferring responsibility for justice from me to the jurors.

“Soon you will march out of here and into the jury room where your decision of justice will be made. Perhaps you have looked forward to this moment. Perhaps you have dreaded it—this moment when you will be called upon to pass judgment on another human being. It is a frightening time for me. In a few moments I must give up my client to you. In a few minutes I must entrust this case into your hands. I do not want to let go. I am afraid.

“What if I have not done my job well enough? What if I have failed in creating the same level of caring for little Polly and her parents (in the criminal case, Jimmy) as I care for them (him)? Yet, in the end, I trust you. But this is a hard time for me.

“Before I leave you I want to share with you a story I tell in nearly every case. It’s about transferring the responsibility of the case from us, on behalf of little Polly and her parents, to you, the jury (or on behalf of Jimmy to you, the jury).

“It’s a story of a wise old man and a smart-aleck boy who wanted to show up the wise old man as a fool.

“One day this boy caught a small bird in the forest. The boy had a plan. He brought the bird, cupped between his hands, to the old man. His plan was to say, ‘Old man, what do I have in my hands?’ to which the old man would answer, ‘You have a bird, my son.’ Then the boy would say, ‘Old man, is the bird alive or is it dead?’ If the old man said the bird was dead, the boy would open his hands and the bird would fly freely back to the forest. But if the old man said the bird was alive, then the boy would crush the little bird, and crush it, and crush it until it was dead.

“So the smart-aleck boy sauntered up to the old man and said, ‘Old man, what do I have in my hands?’ And the old man said, You have a bird, my son. Then the boy said with a malevolent grin, ‘Old man, is the bird alive or is it dead?’

“And the old man, with sad eyes, said, ‘The bird is in your hands, my son.’

“And so, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, the case of little Polly (or the life of Jimmy) is in yours.”

In the civil case, preparing the rebuttal first. As a young lawyer I lost an important case because I hadn’t prepared a rebuttal. The purpose of rebuttal in a civil case is to show that the defense’s argument is wrong, or incomplete, or not relevant. I thought, how could I prepare my rebuttal argument until I had first heard what my opponent argued?

So I was listening hard, furiously making notes. I was not only listening to his argument, but at the same time I was trying to come up with an argument to rebut it. I was attempting to make notes on both what he said and what I would say back. I began to panic. “Oh my God. I can’t remember what he just said because I’m writing what he said before, and now I’ve got to hear the next thing that he’s saying and make a note as to what my response will be,” and suddenly I was lost. His argument was overwhelming me, and when I got up I was not only frightened but confused as to how to organize my last words to the jury.

If during the planning stage of our final argument we reverse roles with our opponent, as we have so often in this book, we will have anticipated nearly everything that our opponent is going to argue. If we have taken time to prepare our rebuttal argument in the quiet, it will be simply brilliant. The few points that we need to add we can add with ease. The few points we may overlook will not be important. We have been in control of our rebuttal, not our opponent, and we will win.

Listening to the opponent’s argument. Over many years I have learned that the sound of the opponent’s voice will tell me if he is saying something important—at least to him, and if it’s not important to him it will not be important to the jury. I simply close my eyes and listen to the sound of his voice. Often his argument will be mumbled, spoken fast, delivered in technical, dull language or otherwise dumped on the jury with little or nothing to cause one to take notice. Why should we answer those arguments? By rebutting them, we call the jury’s attention—probably better than our opponent has—to issues or facts the jury likely paid little heed to. Only when I hear the excitement in his voice, a vibrancy that stirs me, do I choose that point as one to be answered.

Other arguments in the criminal case. In the criminal case we are fighting for freedom. The life of our client, and, indeed, our own, is at stake. When the jury brings in its verdict, it is as if our necks are stretched out on the chopping block as we await the fall of the ax, or mercifully the ax will be withheld when the clerk reads the magical words of life, “Not guilty.”

Of course we will argue the facts as they show innocence or as they (more often) show the failure of the state to make its case. We will remember with the jury the flaws we encountered in the state’s case, the lack of proper investigative procedures, the carelessness of the officers, the fact that others could have committed the crime, the unreliability of eyewitness identification, the motivation of snitches to lie, the infamous characters that surround the prosecution as witnesses, the need of the prosecutors to convict at any price, the suggestion of behind-the-scenes shenanigans, the failure of scientific evidence, the tests that were not made, the state’s experts who were mere lackeys, whatever unfair tactics were put into play by the prosecutor during the trial, the witnesses that should have been called but were not, the evidence that should have been preserved and presented and was not, the failure of the state to prosecute the big shots instead of the easy mark—the powerless defendant, the absense of the proof on each element of the crime, including the failure to prove a criminal intent, the interest of others in using the criminal processes against the defendant for their personal gain, and whatever other facts and issues exist that should be argued. All of these questions point to the defendant’s innocence, the lack of sufficient evidence to prove his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, or, indeed, the injustice of finding the defendant guilty under the circumstances of the case—something called jury nullification, which we shall consider in a moment.

Arguing reasonable doubt and the presumption of innocence. All of us are presumed innocent, or so the old saw goes. But once the charges have been leveled and made public we are presumed guilty. The human brain is incapable of graciously bestowing on the accused the presumption of innocence. We have been fooled too often. Corruption among the most respected members of our community is rife. Poor people rob as well, but not as efficiently. Crime on and off the streets is rampant. You can’t tell the innocent from the guilty by looking at them. They can all look innocent. Then the realization begins to sink in: They look innocent, act innocent, are presumed innocent, but they are guilty. If they weren’t guilty, why would the prosecutor charge them? Where there’s smoke there must be fire. So much for the presumption of innocence!

But if at the beginning of the trial the jury sees Jimmy as probably guilty, the presumption of innocence becomes merely a meaningless technicality, leaving Jimmy with the burden of proving his innocence or going to prison (or perhaps the death house).

Yet under our law the defendant is not required to prove anything. The total burden of proving him guilty rests with the state. So what do we do when we know that the jurors do not, cannot and will not see our client as innocent from the start? I often discuss this phenomenon with the jurors during voir dire. The discussion might go like this:

“Do we really believe that Jimmy is innocent?” I wait for an answer. Not one of the prospective jurors raises a hand. I might then turn to one of the jurors. “Mr. Abernathy, do you believe Jimmy is innocent?”

“Of course, you are right. You don’t know. But the law says that Jimmy is presumed innocent. What does that mean to you?”

“It means that we should see him as innocent.”

“But in our hearts we think he is probably guilty, don’t we? I mean, that’s what I thought when his file was handed to me, and I was assigned his defense. This man is just another one of those criminals who now wants us to think he is innocent.”

“I don’t know.”

“When we are told to presume Jimmy innocent, we are simply being told by the judge that his being charged here with these crimes means nothing about whether he is guilty or innocent. It means that the prosecutor has to prove his guilt because he is presumed innocent. How will we remember that during the trial?”

“We’ll just have to remind ourselves, I guess.”

“Yes. Thank you, Mr. Abernathy. And I will try to remind us as well.”

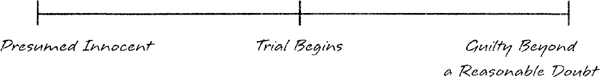

Simple visual aids are often more effective in making a point than a wheelbarrow full of words dumped on the jurors. In the final argument I may go to the blackboard or flip chart and draw a line: Then on the line I may insert a middle point on the line. I say to the jury, “This is where the trial begins. No evidence had been given to you at this point. Now, this is where the prosecution must go to prove Jimmy guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.” (I then mark the far right end of the line labeled GUILTY BEYOND A REASONABLE DOUBT.) “And this is where Jimmy is throughout the trial—even to the moment you go into the jury room to deliberate.” (I mark the far left end of the line labeled PRESUMED INNOCENT.)

“Now, folks, the prosecutor’s proof must be so clear, so convincing, that his proof has caused each of us to move the place where Jimmy is, presumed innocent, from the far left of this line to the far right of this line. Even now Jimmy still sits here presumed innocent. The evidence of the prosecution has come and gone. It has been examined and cross-examined. And after these many days of your patient listening and consideration, nothing has budged Jimmy from the safe place where the law places him and each of us who may be charged with a crime—that is, he was presumed innocent to begin with, and he is still presumed innocent because the prosecution’s evidence has failed.” At this point I may begin my dissection of the state’s case.

And this business of reasonable doubt—the defendant says the state must prove every element of the crime charged beyond a reasonable doubt. But what is reasonable doubt?

That which is reasonable doubt to the accused is just so much lawyer talk to the prosecution. The prosecution sees reasonable doubt as a stew of unreasonable arguments meant to mislead the jury from its bounded duty to convict. To the defense, reasonable doubt is the safeguard provided every citizen to protect against the conviction of the innocent. Jurors may have their doubts, all right. There may be those arguments revealing that every crack in the case has not been sealed shut. But what if the juror embraces a reasonable doubt argument and a guilty man is freed to commit a similar crime again? What if a serial killer has been created by the juror’s vote for acquittal based on reasonable doubt?

The defense of reasonable doubt is more readily accepted by the jury when the crime is one of passion, where the likelihood of a repeat performance is not real, where there is sympathy for the accused, where the alleged crime was morally justifiable or humanly understandable—the wife, for instance, who is charged with murdering an abusive husband; the husband who is charged with having beaten up a person who has intruded into the sanctity of his marriage; the accused who is charged with murdering someone who was morally depraved. But beware the argument of reasonable doubt where the accused may be a vicious murderer.

Jurors will not chance their own potential guilt for turning a killer or a rapist loose. There may have been reasonable doubt, all right, but under those circumstances reasonable doubt is merely an argument. And like all arguments, it can be rationalized into oblivion.

In such cases, perhaps the argument of reasonable doubt would sound like this: