In August 1979, the Salzburg Festival was in full swing. Herbert von Karajan was directing a new version of Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida, and the famous opera and symphony director Karl Böhm was directing his last opera at age eighty-five. A quarter of a million people filled the concert halls and outdoor stages for more than two hundred performances of symphonies, plays, and operas. Every hotel was sold out. There was no room at the inn, except at the Unfallkrankenhaus, the trauma hospital where Dave and I found ourselves in a second-floor, two-bed room.

The view of the beautiful, romantic old city contrasted with that of our sterile, austere room. From our balcony, the timeless charm of the Old Town stretched out before us as Dave and I straddled two worlds. Inside the sparse, utilitarian hospital, we were starting over, with grueling work ahead of us. Outside, picturesque Salzburg beckoned us to dream of the beauty that still surrounded us if we were just willing to reach for it.

“Hey, Linda, your shoulders are even. Good job,” Adrian said as she approached.

Yes! Progress.

“We brought you some dinner,” she said.

“A very special dinner, a dinner for two,” Johnny said. He held aloft a covered dish, as if presenting a sacrifice to the gods.

“But before you eat these little guys, you’ve gotta know the story.” He paused, as if for permission to proceed. “Now, the best way to find Schnecken is to set out on a forest path early on a Sunday morning with sturdy shoes, a walking stick, and a plastic bag. Keep your eyes peeled for these critters slithering along the path. Make sure you carry a Schneckenring so you know whether they’re big enough to take and keep. The last thing you want is Der Waldmeister to arrest you for poaching.” He had a twinkle in his eye.

“On a Sunday, huh? Not Saturday morning or Thursday afternoon? Sunday. Sunday morning?” Dave teased.

Johnny laughed and didn’t skip a beat. “I take them home and dump them into a large, heavy-lidded crock, where they stay for a week or ten days, feasting on cornmeal, sweet white German wine, and herbs. What a life! When the purification is complete, we boil them in a large pot with more wine, herbs, and water. After they cool, I pull them out of the shell and rinse them. Meanwhile, we boil the shells, saving them for presentation when we eat them. To serve, you warm the stuffed shells, place them on little escargot trays, and serve them with melted butter, fresh bread, fruit, and cheese.”

“Which we have right here,” Adrian said as she pulled a loaf of bread from a local Bäckerei and several Tupperware containers out of her shoulder bag.

I squealed and without thinking tried to clap my hands together. The sudden movement and momentum sent me listing starboard.

“All right, help me up, someone. I can’t eat like this. I’m just grateful you took them out of the shells already. Nora would insist that I find a way to hold the tong in my left hand while using the fork with something else—something, anything, other than my teeth!”

We all laughed. Johnny set the dish down on the bedside table and pulled my high, cane-backed wheelchair over toward the bed while Dave gently scooped me up and set me in it. “My lady, may I escort you to your table?” he said.

“Yes. Please do. I’d like a view, please, something with a breeze, if you can,” I said, using my most aristocratic voice and better-than-thou face.

“We have just the place,” Dave said. He wheeled me through the sliding glass door, which opened onto a tiny balcony just big enough for a small table and two chairs.

The magic of the evening overpowered us. Below was a grassy area with large shade trees, walking paths, and a small gazebo. Beyond, the stunning view of the Hohensalzburg Fortress captivated us. Its massive whitish walls fade into a tan patina. Crenelated towers flank the corners, and small rectangular windows march along the tops of the walls, breaking the sameness. It consumes all the space on the largest hill overlooking the Old City. Adding to the charm are nearly a dozen delicate spires of old churches that rise to the base of the fortress. We felt like a king and queen that evening, looking over the city while the centuries-old fortress compassionately held vigil over us.

We gazed at this mesmerizing fairyland every day, letting it transport us to a place where everything was serene and happy. The undefeated citadel on the hill gave us strength.

Evenings became our special time together. We had no energy to waste on pity, regret, or anger. Exhausted but anxious to create our new normal, we primped, smoothed the bedsheets, and settled in with each other by nine o’clock. Someone had brought us a copy of The Winds of War by Herman Wouk, and its recently published sequel, War and Remembrance. Each had more than a thousand pages of war, romance, and intrigue, with enough historical accuracy to bring it to life for us. The sex scenes made me blush and cast furtive glances at Dave. I wondered if we would ever feel those things again.

One afternoon, Donna and Adrian sashayed into our room, giggling like schoolgirls. Adrian dangled a pretty wrapped box over my bed.

“Looky here,” she teased, holding it just barely out of my reach. “Come get it.”

I scooted toward her an inch at a time, reached out without tipping over, and snatched it away from her. “Ha haaa,” I said. “Guess I showed you!”

Feeling a little smug, I dropped it on my lap, then realized I’d have to untie the bow, remove the string, undo the tape, and get the lid off. I snuck a look around the room, making sure a commando nurse wasn’t watching, grabbed the ribbon with my teeth, and pulled. Voilà—out spilled a dainty set of white eyelet-lace baby-doll pajamas—the kind that shows lots of bare skin and cleavage.

I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. I held the skimpy top at arm’s length and waved it back and forth. Oh, heck—why not! I jiggled my boobs free of my hospital gown and tried pulling the top over my head. The little straps hung on my ears. I wobbled precariously, trying to jab my left hand into the armhole. Dave was at my side almost instantaneously, gently tugging it down over my shoulders. Before I could stop him, he fondled my boobs and planted a loud smooch on my cheek.

The elephant in the room couldn’t be avoided. Someone cackled; others averted their eyes. I had no idea how or if that was going to work in the long run, but at least, for the time being, he was acting interested.

The sexy pj’s became my signature look.

By the end of the first week, everyone in the hospital knew who we were. The most glaring reason was that we were always speaking English and they were always speaking German. Our families had relatively free rein to come and go as they pleased. Nurses would linger longer than necessary in our room, and I’m quite sure we had more than the usual number of doctor visits during the day. Maybe the “free rein” was because of our language differences and we just didn’t know any better. But maybe it was because our independent, adventurous American spirit made us somewhat of a delightful distraction.

At the end of every day, our families found their way back to their quarters at military housing in Berchtesgaden, emotionally exhausted. There were usually ten or eleven people: Dave’s family, my family, and Adrian and Johnny. They were the grateful recipients of a steady supply of homemade food that arrived frequently from the military base in Stuttgart. Johnny’s commanding figure opened the bar early every evening, and in his infinite wisdom he titrated the evening’s gin and tonics as he felt necessary.

I’m told it was my dad who first suggested that they dance. He and my mom had been taking ballroom dancing lessons for the past few years and enjoyed practicing to big-band music on the tile entryway of their home in the evenings before dinner. We had grown up as strict Seventh-day Adventists, a religion that disapproves of dancing. This departure from our upbringing had been rather momentous a few years earlier. I can imagine my father standing up and stepping into the middle of the room, beckoning my mother, who of course would demur at first but finally hold her arms out to him as they came together for a romantic waltz or a fox-trot or maybe even a little cha-cha. I’m sure Dave’s parents and Adrian and Johnny were quick to follow. Anxious faces tentatively smiled, then laughed, and then maybe there was even a chorus or two of Frank Sinatra or Peggy Lee.

One night, after a few of Johnny’s “stiff ones,” they got down to business and created a society to record and track the progress of my recovery. I’m still amazed at the name they came up with. They must have gone around the circle and asked everyone for a word to incorporate into the title.

From:

The Society for the Serendipitous Restoration of Social, Scientific, and Sexual Scintillation Among the Amorous, Erotic, and Occasionally Erratic Emmigrants [sic] to the Bavarian Barracks in Berchtesgaden

To:

The Famously Fantastic, Fabulously Realistically, and Resolutely Responsive Regenerates Confined in a Cozy Corner of the Krankenhaus

Greetings:

Having duly considered cautiously the characters of the confinees in question with the definite difficulties that developed, undoing (temporarily) the doings of the most durable doers in the domain of diabolical diagnostic designers, the Society awards the meticulous marks in management measures initiated by the ingenious ingenue and her consort in commodiously comfortable Krankenhaus cohabitation.

Bertchesgaden University for Mature Students

“BUMS”

Every afternoon, our families and friends straggled in with time weighing heavily on them. This seemed harder in some ways on them than it was on me. Their helplessness and my need for fresh air gave me a mission.

“I can’t stand it in here anymore,” I blurted out one afternoon. “I’ve got to get out of here! Let’s find a way to get outdoors before I go stir-crazy.”

“Great idea, Olsie!” Dave said.

The next time Nora stepped into the room, we pleaded with her to help us make a plan. “Do you think you could find a wheelchair for Linda so I can take her outside for some fresh air?” Dave asked.

She swung around and said, “Nein, you can’t push her out there. You need to be in a wheelchair, too!” And with that, she swept out of the room. Five minutes later, she returned with another nurse and two cane-backed wheelchairs.

“Okay,” she said to the other nurse. “On the count of three, let’s lift Linda and put her in this wheelchair. Eins, zwei, drei.”

I clenched my fist and squeezed my eyes shut, hoping I wouldn’t scream. They put me down gently and wrapped me in a snowstorm of white sheets and blankets. Dave settled himself into the other chair, a brown hospital robe over his hospital gown. Off we went on our first wheelchair adventure. Hospital fashionistas, we made our way down to the ground-floor lobby.

“Do you see what I see?” I asked as we neared the lobby gift shop.

“Uh, yes. Flowers, cards . . .” And then he did a double take. “Beer? Are they selling beer in a hospital lobby?”

Suddenly, we had a plan.

When everyone arrived that afternoon, we loaded up books and blankets. Adrian and Dave’s brother and fellow accident survivor, Mark, rolled our wheelchairs down to the lobby where we bought a few bottles of beer and then paraded out to the garden. From then on, we held court outdoors every afternoon in the warm September air smelling of cut grass and happiness. Some days there were up to seven people, all of us taking turns at playing the role of jester. We tried to outdo each other with jokes and funny stories, becoming more ribald as the afternoon shadows grew longer. My goal was to make everyone laugh and see the future as full of possibilities.

My surgeons, having seen Dave show that he’d had plenty of surgical experience, happily allowed him to be doctor to me when they weren’t around.

“My, you’re healing up nicely, ma’am. No more catheter, no more IV,” he said with an impish smile one morning after my doctors had made their rounds.

He went about his work. After a few minutes, he said what had obviously been on his mind the entire time. “And your boobs are perfect. Your bottom’s perfect, too. You’re still a turn-on.”

“Doctor, I don’t believe your behavior is appropriate. What would the hospital administrator say?” I responded coyly as the back of his arm “accidentally” slid over the thin fabric separating my boobs from his body.

“I’m just being friendly,” he said with an unapologetic grin.

It sounded good. It felt good. But it was still hard to see myself as sexy Linda. Playing doctor was one thing. But Dave played nurse, too. He attended to my basic bodily needs and administered medication, for the most part, by suppository, the Austrian-German way. Those images were hard to shake and replace with the way things had been.

But that night, after everyone had gone and all was quiet on the hospital floor, he became husband again.

I watched from my bed as Dave, still in his cast, hobbled around the room, doing some tidying. He caught my eye and stopped at my bedside, leaned over, and kissed me softly on the lips. It felt good. Really good.

“Mmm, let me touch you,” he whispered.

“Are you sure?” I asked. “Are you sure you want to? How can I possibly turn you on?”

“I’ve been dying to for days,” he responded.

I smiled and let out a giggle before the reality set in. “Well, okay, but I don’t know what will happen,” I said.

“You’re neurologically intact. Let’s see what’s going on with the supratentorial part, shall we?” he whispered.

He kissed me gently on the lips, carefully reached his hand under the sheet covering my lower torso, and found the sensitive area. He was soft and gentle and slow and patient and found that the sensitive area was just as sensitive as it had always been. After a few minutes, I moaned softly, and all the tension of the past ten days left my body in one exhale. We were lovers again.

“Mmm, that felt so good,” I murmured after a few minutes. “But what about you? I can’t do anything.”

“Don’t worry about me. I’m fine,” he said. It was clear to see that that was a lie! I smiled and winked at him—a small consolation prize, but all I had to offer.

“And we just proved that you are, too, so I can wait. But I will make you pay me back when you can. You’re going to have a pretty large accounts payable by then!”

“Ooh, okay,” I said, giggling. “I’ll look forward to that! You better be ready.”

A little friendliness had crept into the Salzburg trauma hospital. That night in bed, wrapped around each other as much as two people with three good arms and one good leg between them can, we sighed the collective sigh of partners climbing back up the steep cliff from which we’d been so unceremoniously thrown.

In the second week of our recovery, a petite, young, blond occupational therapist walked in one morning and introduced herself.

“Ich heisse Sonja. Wie heissen Sie?”

By that time, I had an automatic response to anyone who came into our room speaking German. I’d flash my big smile and say either “Guten Morgen” or “Hi, how are you?” It didn’t matter which, because as soon as I said it, indecipherable German words flew out of their mouths, and all I could do was up my smile a notch and shrug my shoulders.

Responding to my Help me! look, Dave jumped in. “Guten Morgen, Sonja. Wie geht es Ihnen?”

Then he turned to me. “Say, ‘Ich heisse Linda.’”

She smiled expectantly at me as she placed a pencil and piece of paper on the bedside table. She took out another piece of paper and showed me a list of words. With gestures and pointing, she indicated that she was going to dictate them to me so I could write them down.

“Der Hase” (the rabbit), she said in a slow, deliberate voice.

I gave her a confused look.

We laughed as I tried to pronounce each word on her spelling list. I failed the German vocab test, but I assiduously practiced writing them every day.

As had become our routine, when the hospital quieted down in the evening, we shifted into work mode to grapple with how to re-create our lives. Dave took charge and made things black and white. We shared our fears and frustration, but he went a step further and made me put pen to paper and write a list of the issues we were facing.

“Hon,” he said one night, “yesterday I asked Adrian and my mom if they’d bring us a notebook and something to write with.” Reaching into his nightstand, he pulled out a tablet and notebook and limped over to my bed. “Which would be easier for you, a pen or a pencil?”

Pen or pencil . . . I don’t even know how to hold a stick in my left hand. How can I even make this minor decision? I opted for the pen. Maybe the words I write will be stronger and come to life.

Where do you start when you have to start all over at age twenty-nine? Can you categorize your life in a list on one page? How many words does it take?

Looking back at the pages we saved from those nights, I see the answer. The first page has ten categories: Personal, Rehabilitation, Professional, Social, Marital, Family, Psychological Adjustment, Sports Activities, Occupational Adjustments, Desirable Goals. The words tilt up and down on the page in my second grade–looking print. Four more pages provide ideas and details about how we might proceed in moving on with our lives. They are poignant in retrospect, the result of much soul searching at the time.

“I’d like to send a postcard to the White,” I told Dave one morning.

The White Memorial Medical Center in Los Angeles was where I was doing my radiology residency. This was my first attempt to reconnect with my career.

Like magic, a pen and postcard of the Mozartplatz appeared on my hospital bed stand. Even though I’d been practicing for a couple of days, my left hand fumbled with the pen. Should I hold it with three fingers or four? Where should my thumb be? The edge of my hand covered most of the postcard as I tried touching the pen to it. How am I supposed to write and keep this stupid little card from moving around?

“Can you bring over that coffee mug and set it on the corner of this card?” This is downright hard, if not impossible, but I can’t imagine someone holding things for me the rest of my life. So come on, Linda—just get over it and figure it out.

Dear Rad Gang,

I couldnt [sic] have found a prettier town to have been incarcerated in. They have let me look at my X-rays before and after. They’ll make an excellent teaching file. This is one of 6 hospitals in Austria for trauma only. We’ve had exellent [sic] care. You can all do us a big favor by finding the best rehab cent and prosthesis [sic]. Love, Linda

The first three words run up- and then downhill: “Dear Rad Gang, I couldnt [sic] have found a prettier town to have been incarcerated in.” I choke up a little as I start. I try to make it sound positive (“prettier town”) and make fun of it (“being incarcerated”).

My childlike handwriting continues: “They have let me look at my X-rays before and after. They’ll make an excellent teaching file.” Every radiologist in the country knows what a teaching file case, or TF, is: radiographic images that show something unique, or classic, or difficult to diagnose. Teaching file cases are fascinating to look at but are almost always bad news for the patient. My X-rays were certainly worth the proverbial thousand words. Then again, you don’t need to see my films. The diagnosis is visible to the naked eye.

“This is one of 6 hospitals in Austria for trauma only. We’ve had exellent [sic] care.” This is really weird—I can’t spell. It is shocking to write a sentence and discover that several words have letters or whole syllables missing. I forced myself to spell the words out loud and then squeeze in the missing ones haphazardly. I hadn’t given a thought about how to spell these simple words since I was in second grade.

It’d been many years since I’d given a thought to many things. Suddenly, I was forced to rethink everything.

“Be careful. Don’t let them psychoanalyze you.”

Mal Braverman, MD, was a psychiatrist from Beverly Hills who had been doing research on burn victims in the Unfallkrankenhaus. A tall, husky man, he’d introduced himself by saying he’d heard a lot about us. Dave and I liked him immediately. A warm, friendly person, he spoke with us for about an hour. I described the accident, telling him I’d been conscious the whole time. Together, Dave and I told him our deepest feelings and worries, and shared the plan we’d put together for the future. He questioned both of us. Psychiatrist questions. He watched and observed us.

“I’d say both of you are handling this problem just fine. No doubt it will be tough. I’m pleased to see how well grounded you are and what you’re doing. When you get back to the States, they will want both of you to undergo counseling and analysis. Don’t let them dig into you, because I know they’ll want to go into deep, Freudian-type psychoanalysis, and neither of you needs that.”

We were stunned but pleased and promised to take his advice. It had been only two weeks since the accident, and I’d had no nightmares or panic attacks and was not reliving the accident. But, having no experience with the mental consequences of trauma, we were unaware of the potential for long-term sequelae. Unbeknownst to us, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III) was being revised to include the change from “gross stress reaction” to “post-traumatic stress disorder” and was evoking a lot of attention. Dave and I were strong individuals, and deep down we felt that if we combined our strengths, we could work through this as a team.

“Ahem,” Johnny said. He held himself up straight like the commanding Navy officer he was, demanding the attention of the court.

The breeze blew through the trees, and had it not been for my disfigurement and bawdy attire, it would have been easy to mistake our party as a group of tourists enjoying a secret garden tucked in a fold of the ancient city. In many ways, we wanted to stay, but it was almost time to go.

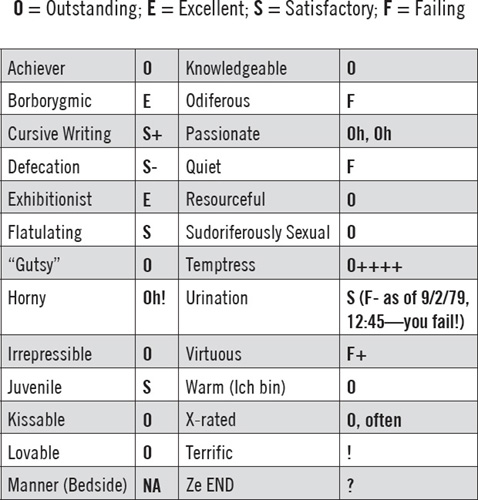

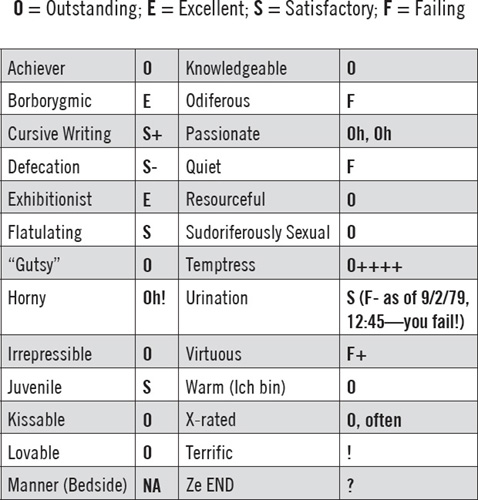

“May I have your attention, please?” Johnny continued, theatrically snapping a sheet of paper in front of him. “The Society of Sexual Serendipity presents to you, Dave and Linda, your Report of Progress!”

Our families and friends guffawed as they took turns reading aloud their assessment of our recovery.

Our last night in the Salzburg hospital came in late September. Five doctors filed in and stood at the foot of our beds to bid us an emotional farewell. Three and a half weeks earlier, these vastly experienced, gray-haired, stern trauma surgeons had saved my life. The one who was fluent in English spoke for them.

“We have something we’d like to say. We’ve been watching you for the past three weeks. If you were Austrian, you might not have opened your eyes yet. You have shown us what we believe is the American spirit.”

Dave and I were silent, not wanting to break the spell. We knew it was time to leave the Unfallkrankenhaus and our castle on the hill, which had brought us deep fear and magical hope. By then, I knew that Dave’s love would give me the power to prove these men right.

Six weeks short of my thirtieth birthday, I found myself strapped to a gurney in a back room of the Salzburg airport. Dave stood next to me, holding my hand, the only one I have now. We felt naked. We were leaving the trauma hospital where we’d been for three and a half weeks. Our hands were free of luggage, but our minds were full of baggage. We were going home, back to what we knew, but everything was unknown. Breathing was the only thing left that was automatic.

I was a baby, tiny, no clothes, beginning a journey on which I must start over, learn a new way to do everything, from sleeping on my side to dressing to sitting in a wheelchair, and to getting people to see me, notice me, know me.

We were silent. There were no words for where we were. Even though our minds overflowed with questions and fears, we knew it would do no good to verbalize them. It is time for me to grab hold of myself and take charge, I thought. At the same time, I knew that I must let Dave hold me and take care of me until I could do things by myself again—if I could ever do anything by myself again.

Through the large plate-glass windows, I saw the tarmac stretching away from me, vanishing. At intervals, planes roared in and throttled off. Nothing stays still. Everything is coming or going, and while the passengers inside them think they know their destination, I wondered how many of them, like us, would not end up where they thought they were heading.