“Dave, I’m ready,” I said, a little too sharply. It was the 6:30 a.m. ritual, and I detested it. I’d powdered my stumps, pulled the pantyhose on them, strapped on my fake legs and was squirming in my wheelchair. It was spring 1980, and we were living by ourselves in Dave’s parents’ house in San Diego.

“There’s gotta be a way for me to put these on by myself,” I grumbled as he knelt on the floor. I levered up and grabbed the edge of the dresser to steady myself. Dave, on the other hand, grinned lasciviously as he scooted in between my legs and looked up my crotch while he wrapped the loose end of a nylon around his wrist and pulled down to snug my leg into the socket of my prosthesis.

“Ooh, I like your panties,” he said. “Especially these black ones.”

I rolled my eyes and wished he’d hurry up.

“Hon, you’ve got the cutest ass. This is my favorite time of day.”

“Well, I hate it. I hate being dependent, and I hate having you work so hard all the time.” My voice choked and I gritted my teeth, trying not to turn this into a bitch session.

“Well, I love your black panties, and you turn me on.” We had some variation of this conversation every morning, always initiated by Dave and always ending with a hug and a kiss when my legs were finally on. I smiled in spite of myself.

Dave rolled out of bed at four thirty every morning and pulled on an old T-shirt and shorts so he could get in a seven-mile run before six o’clock. Then Mr. Sweaty Body would haul me out of bed and plop me down on the floor of the shower, and we’d giggle a lot while lathering up—my turn to sit between his legs. There was no time for dilly-dallying, though, because every minute was scripted so we could eat breakfast, get my legs on, and get out the door. Dave dropped me off at the VA hospital or UCSD Medical Center, Hillcrest, and then drove downtown to the Naval Regional Medical Center in Balboa Park.

Eternal dependency was one of my earliest fears in the first days after the accident. Being incapable of going to the bathroom by myself, clumsily trying to eat, unable to move without assistance. Powerless, impotent, incapable, inept, inadequate, weak, unfit. Helpless. These words had never been in my vocabulary. Now they haunted me.

“Well, you know I can’t go back to LA if I can’t get these things on by myself.” There. It’s out in the open. I wanted to be able to live on my own again. I wanted Dave to be on his own again. And what if the worst happened? What if Dave decides he’s had enough and leaves me? I wondered.

“I’ve got some ideas about something I can make that might work.” One more tug on the last nylon; then he shoved the end of the nylon into the socket and screwed in the valve. “Something you can lean on and that will support you if you lose your balance; something to take my place. Sit down, and I’ll show you what I’ve drawn.”

Something to take his place. I hoped that would never happen, but I guessed it’d be good to be prepared.

The sketch was not much more than a scribble, but it looked brilliant. A three-by-three-foot piece of plywood on the floor with four vertical metal pipes, one attached at each corner. Horizontal bars would attach the tops of the pipes to each other, leaving one side open, like a square with one side missing.

“You can push your wheelchair up to the open side and lock it in place. Once you’ve pulled the pantyhose up on your residual limbs, you’ll reach for your prostheses, pull them to you, and slide them onto your stumps. Then you’ll buckle the straps around your pelvis and waist and stand up. Once you’re upright, you can lean over, with the back bar supporting your waist, reach down and grab the ends of the nylons, and pull yourself the rest of the way into your prostheses.” He paused for a moment to take a breath. “After you tuck in the ends of the nylons, you can screw in the valves, push yourself upright, pull up your jeans, and voilà—you’ll be whole again!”

I laughed out loud at the cartoon in my mind. The upper half of a person rolls in to meet up with a lower-half person. A few grunts and groans later, the torso can ambulate and the legs can vocalize.

“If you stand up, I’ll measure you so I’ll know how tall to make Iron Mike.”

“Iron who?”

“Iron Mike. Your new best friend,” Dave replied.

Hmmm . . . a ménage à trois? Why not!

Grasping the left armrest of my wheelchair and pivoting on my right heel, I strong-armed myself forward, hoping like hell that I wouldn’t push so hard that I toppled over and smashed my face.

“See,” Dave said, “Iron Mike will keep you safe when I’m not around. If you push too hard getting up, he’ll catch you with his strong metal arms so you can’t fall.”

Dave’s sketch became a reality. A week and sixty-five bucks later, the three black arms and four black legs came to life in the family room. That night, I unstrapped my legs and propped them in Iron Mike’s embrace; they reposed there while Dave carried me upstairs, where the rest of us slumbered. One more step on my road to independence.

By midspring, I walked well enough that Dave started taking me to the VA hospital to spend the day in the radiology department where I sat in on readouts and conferences. It was the easiest way to build my strength and learn how to maneuver without the responsibility or pressure of reading films. For a few minutes a day, I felt a flash of my old self when I made the correct diagnosis on an X-ray image.

For the first few months, all I thought about was walking. No, actually, what I really thought about was falling. My toy-soldier gait is unique, and in case people didn’t see me, they’d definitely hear my thump, thud, thump, thud cadence as I made my way slowly down the halls. Even though I’m a small person, I take up a lot of space as I walk with my wide-base stride, by placing my cane out in front of me and to the left to protect the space around me. My biggest fear was that I’d be knocked down, so I hugged the right side of hallways, hoping the wall would break my fall if I lost my balance. Imagine walking on stilts with knees.

I thought back to the first lists I wrote with my left hand the week after the accident. We were making good progress, but the clock was still ticking on one thing: finishing my residency. My yearlong medical leave of absence would be complete at the end of August, so I had to be back to work by September 1980 to fulfill the last nine months of my residency. If I was even a week or two short of training, I’d have to wait another whole year to take the exam—an unacceptable option.

Dave and I had been in complete agreement about the importance of my becoming a radiologist. I’d spent many hours during the weeks in Salzburg dreaming and planning my return to finish my residency. In my bleakest hours, I found hope by imagining myself at a radiology viewbox—dictating films, calling clinicians with results, joking with my colleagues. All of this typically happens in a darkened room—a room in which people wouldn’t see my missing legs and arm, a room in which my radiologic interpretations would help my fellow doctors save lives and my empathy and humor would brighten the day.

When I had my doctor hat on, it was easy to forget my funny walk and missing arm. I felt worthwhile and needed.

“Do you think you can find a roommate? Would your sister live with you again?” Dave was washing the dinner dishes. It had been a month since our return from Europe, and both of us were tired. A fork slipped out of my hand and clattered to the floor.

“I love my sister but I don’t want a roommate.”

“I know, but you’re pregnant. This is my baby, too, and I can’t help you when I’m one hundred and ten miles away. What if you fall? How are you going to get help? How will you get to the phone?” His voice kept getting louder.

I froze, unable to respond. I was going to LA no matter what. Dave’s temper and my passivity or aversion to confrontation are an issue between us. He can “see red” instantly. It takes me forever to get mad. But watch out—if you push me enough, I won’t talk to you for three days. “You ass-holy shithead” is my favorite term of endearment for him when I’ve reached that stage.

I took a deep breath and waited. I was concerned about him. I suspected that this accident and recovery were easier for me because I could take physical control and work hard to make things better. The more I sweated, the stronger I got. While Dave obviously did most of the grunt work, he had more mental uncertainty. Am I physically strong enough to do what the doctors have said is not possible? Will I persevere? Will I get depressed? He also had more anger about the accident than I did. And then financial security was a huge issue. It was going to cost a lot of money to modify or build a house, to adapt a car for me to drive, to pay for household help. And finally, who would take care of me if he couldn’t, and what would it cost?

I was convinced that his addiction to running was probably what would save him. To him, a day without running is worse than a day without food. It’s where he sorts through a myriad of issues, airs them out in his mind, creates solutions, and packs them back into his brain so he can deal with them as the day wears on. I learned only recently how he felt and what he did on those early morning runs the year after the accident.

The radiology department at UCSD had offered to let me finish my residency there, but I’d declined. It would take a while for me to learn how to operate the equipment with one hand. I’d be unable to perform angiograms, bronchograms, lymphangiograms, myelograms, and some of the less invasive procedures. I was sure I’d be slow at first and might not be able to pull my weight. It seemed better that I return to the White Memorial Medical Center where everyone knew me as a hardworking, gung-ho resident and would be cheering me on. My dad worked at the same hospital, and my parents lived about twenty minutes away, so they could help me if need be. Plus, who could know how my pregnancy would go? But the overarching reason I wanted to go back was so I could live on my own again.

Am I being selfish and self-centered? Am I pushing an even bigger burden of worry onto Dave? I knew that he wanted to take care of but not smother me. He still wanted me to be a doctor but worried that the collision of studying for boards, figuring out how to live by myself, and carrying our baby was an invitation for failure or discouragement or depression. He knew I was strong, but we’d been told that it takes a bilateral above-the-knee amputee four times the amount of energy to walk as it takes a normal person. Add to that the energy that pours from a woman’s body into her baby while it grows, and cap that off with the necessity of studying for boards at least two hours every night after getting home from a full day at work.

After things settled down a bit, I looked at Dave and said, “I’ve made a timetable for myself to start studying.” I handed him an outline of the books I needed to digest in the next twelve months. Lists are our way of tackling problems, and beginning to study would get me revved up for moving back to LA. “If I get started now, I think I’ll have time to review the teaching file at least one last time just before the exam.”

“Sounds reasonable to me,” he said. “While you’ve been doing that, I’ve been thinking about making it easier for you to climb the stairs here at home.” Now, that was big. In the beginning, staircases might as well have been Mount Everest, so I’d put a lot of effort into mastering them.

Difficulty going up and down stairs had been very problematic for me. Everything I needed always seemed to be above or below where I was. This dramatized one of my major shortcomings: disorganization. Dave is constantly annoyed by my “shit piles.” He, on the other hand, is a neatnik who knows where everything is in his life. I’m the one always looking for things, wondering where I left them. It is so like him to be constantly devising ways to make my life closer to normal. I’m going to have to start paying attention to things. I can’t make his life miserable by picking up after me.

“How big is this new man?” I asked, laughing.

“Well, I couldn’t find anyone as strong and good-looking as I am, so I’ve settled on having a handrail installed on the left-side wall going up the stairs.”

The railing was installed about a week later, and we moved Iron Mike up into our room the same day.

“Okey-dokey, here I go.” I wedged my forearm between the wall and handrail, grabbing it tightly. Taking a deep breath, I hiked my right hip up and threw my leg up, levering myself onto the first step. Leaning right, I dragged my left leg up . . . and then I was standing eight inches closer to our bedroom. At this rate, I’d have to start getting ready for bed ten minutes before Dave every night.

The next morning, I stood at the top of the stairs, wobbling a little on the deep, yellow shag carpet. The fastest way would be to butt-slide down, but I didn’t think Dave would be too impressed with that. So I turned around, clutched the railing, leaned over, and, putting my left foot down behind me, proceeded with my drunken-sailor, backward trek downstairs. Each step brought me more independence.

I was scared shitless. It was September 1980, and we were turning into the parking lot of White Memorial Medical Center in Los Angeles. After a year of rehabilitation, I was going back. Back to real life, back to being a doctor, and also back to being an anxious resident who would have to study her butt off to pass boards the following June. I’d had twelve months to get ready. My fiberglass-and-aluminum legs behaved most of the time, and I thought I was ready to be on my own. I’d successfully mastered the activities that Donna, Dr. Gohlbranson, Dr. Webster, and Dave and I thought necessary before I was able to live on my own again: go to the bathroom, sit down and stand up from a chair, put my legs on by myself, bathe or shower, get up off the floor if I fell, go up and down stairs, and walk long distances comfortably with a cane. It had been hard work—sweaty, grueling, and oftentimes discouraging—but I’d done it. We’d done it.

My priority when I got back to work was to identify bathrooms in the radiology department that would suit my needs. Wonder if they’ll let me put up a LINDA’S BATHROOM sign. Likewise, I was choosy about which chairs I sat in. While sturdy chairs with armrests are my preference, I’ve tamed chairs on wheels—as found in most offices—by backing them up to a wall or desk so they can’t roll away from me when I fully extend my right leg, throw myself up with my muscled left arm, pivot around on my right heel while swinging my left leg out into extension, and stand up straight without teetering too much. There are two risks to this maneuver: the chair could tip over or roll away while I land on my behind, or I could use too much force when I thrust myself upright, and then topple over, flat on my face.

I never practiced falling because of the risk that I might break my only remaining extremity, but I mentally prepared for this possibility by telling myself that if I thought it was going to happen, I’d pull my arm in close to my body and tuck and roll, kind of like what big, burly football dudes do every Sunday on national television. I hoped I’d never have to do it.

Setting aside the concerns about living on my own, I knew my primary challenge was to get into a routine of studying for the American Board of Radiology exam. It was a half-day oral exam in Louisville, Kentucky. The first part of board certification was a written exam that I’d passed a few weeks before the accident. Over the next ten months, I’d need to look at thousands of images and read the major texts about seven topics that were on the exam then: musculoskeletal, central nervous system, pediatric, gastrointestinal/genitourinary, thoracic, cardiovascular, and nuclear medicine. I was just like every other radiology resident in the country, trying to balance work with study. But I also knew that I had to pass, because, as a disabled female, I’d never get a job if I didn’t pass the first time around.

And I wanted Dave to be proud of me.

In addition, I needed to figure out how to operate the machines, start IVs, and dictate and interpret films in a timely fashion. I played all the scenes in my mind and had a backup plan for every scenario. Oh, and then there was the fact that I was pregnant.

I was moving back into the high-rise apartment building, located behind White Memorial Medical Center, where I’d lived for the three years preceding the accident. I sat quietly for a few moments, recalling the first time I’d moved into this building—one week after graduating from medical school. My boyfriend, Dave, and I had rented a U-Haul truck in Redlands and gleefully packed my furniture and clothes for the one-hour drive out Interstate 10 to East LA.

He had worked for Mayflower during college summers and knew how to do this. The dishes were packed carefully in paper and stacked in dish boxes; my clothes hung in wardrobe boxes. He’d loaded my furniture, miscellaneous boxes, skis, and all my camping equipment onto the van in military order. My pride and joy had been a classic, mint-green Bianchi racing bike with sew-up tires that made me feel like a superathlete when I sped along country roads in San Timoteo Canyon or up into the San Bernardino Mountains to Oak Glen. There were clothes for every occasion, hiking boots, and shoes. Lots of shoes. Imelda Marcos would have been envious.

We’d giggled and flirted with each other. Deep down, we had a lot of uncertainties. Would our relationship survive the next four years, 110 miles apart? Had we chosen the right specialties? For me, the scariest thing was that, two days later, I’d put on a stiffly starched, new white coat with my name stitched on it: Linda K. Olson, MD. It seemed to me that seven days was not enough to turn a fourth-year medical student into a doctor, but that’s what happens. It was scary to think about seeing patients on my own, writing orders in the middle of the night, waiting for my pager to go off, and possibly not knowing what to do.

I’d been scared and excited then, too, but this time I had a ground-floor apartment that had been graciously modified for my use. Within the first few months after my accident, the administration at White Memorial Medical Center informed us of its unanimous decision to create a wheelchair-accessible apartment for me so I could return and finish my residency. This was a full ten years before the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

As we pulled into the parking lot, I saw my new place and grinned. Dave, my boyfriend turned husband, was grinning and crying at the same time. It was bittersweet to see the newly painted, blue handicapped parking space welcoming us to a ground-floor apartment—a space I wouldn’t be able to use, because I couldn’t drive. It wasn’t clear to either of us if I’d ever be able to drive. Several times I’d sat in the driver’s seat of our car, experimenting with different ideas, like strapping my fake feet to the gas and brake so I’d accelerate and stop, or getting an artificial arm with a hook on it that could attach to a ring on the steering wheel for turning. I always came back to the fact that I’d need two extremities to drive: one for gas/brake and another for steering. My one remaining extremity was strong and worked really well, but it wasn’t extraordinary enough to perform this miracle. I kept pushing down the fear that I’d never be able to drive. I will do anything. It must happen. It will happen. For the time being, I can look out the window and imagine Dave parking his puke-green Toyota Corona there when he comes to spend weekends with me.

A short sidewalk led directly from the parking spot to a sliding glass door that had been modified to become the entry, which I accessed with a remote-controlled, battery-operated garage-door opener. With the click of a button, the door slid open and I could walk or roll in. Click the button again, and the door closed and locked. Pretty cool! A remodel of the bathroom provided me with a wheelchair-accessible shower, sink, and toilet, plus grab bars on three walls.

We brought very little with us. Furniture gets in the way of my wheelchair. A dining room table and two chairs, a small TV, a few kitchen appliances, and, of course, Iron Mike. Dave hauled the mattress and box spring into the bedroom and left it on the floor without a frame. This functioned as a safety backup. If I fell, I could butt-walk across the floor, pull myself up onto the bed, and stand up if I had my legs on or get into my wheelchair if I didn’t have my legs on. I had just a few clothes—baggy pants and formless dresses that I could grow into as my pregnancy progressed—and only one pair of shoes, which stayed on my fake feet twenty-four hours a day.

I’d had my first, temporary set of legs for ten months. Permanent legs are not made until the soft tissues of the residual limb have stopped shrinking, usually three to six months after amputation. But because I was pregnant, things would continue to change for several more months. My doctors decided that it would be best if I waited until after the baby was born for my permanent, suction-socket legs to be made.

Every morning, I pushed myself to the open side of Iron Mike and locked my wheelchair in place. Every morning, I had to look down at my stubby, scarred, and puckered legs that extended only about eight inches in front of me, leaving a lot of empty space in my wheelchair. Pulling a pair of pantyhose up to my waist, I smoothed them over my residual legs and gazed at the twenty to thirty inches of empty, wrinkled nylon that dangled over the edge of the seat. Still seated, I took each artificial leg from its resting place and pulled it partway on what was left of my real legs, threading the nylon pantyhose out through the hole at the front lower end of each socket, thereby tugging my legs partway into the sockets of the fake legs. I crisscrossed the wide, thick white straps over my pelvis and fastened them loosely. Taking a deep breath, I thrust myself upright and leaned over the front supporting rail, knowing that my wheelchair was right behind me if I fell. Grasping the protruding end of the nylon stocking at the end of the socket, I pulled steadily on the nylon so that it slid my thigh as deeply into the socket as possible. Then I stuffed the nylon back up into the small space left inside the end of the socket and screwed a valve into the hole. Left leg first, and then right leg. I stood up and wiggled my legs around to adjust the fit and tightness of the straps. Abracadabra—I was a biped again.

Paramedics leaning over me on the ground next to the van. August 27, 1979. Photo © Bavarian State Police Berchtesgaden

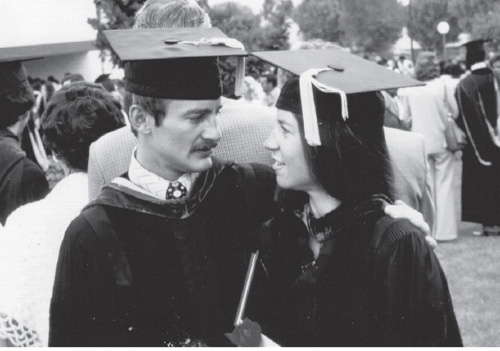

One of the happiest days of my life, graduating with Dave from medical school at Loma Linda University, Class of 1976-A. Photo © Albert L. Olson

Adrian (top left) and Donna (top right) hugging Dave and me a few days after the accident. Afternoons in the hospital garden were excellent therapy, maybe because of the Austrian beers we bought in the hotel lobby? Photo © Jack Hodgens

I endeared myself to my future in-laws by weeding in their backyard. I endeared myself to Dave by wearing a bikini when weeding. Photo © David Hodgens

Vintage Dave running in his “Connie All-stars” (Converse All-Star shoes), baggy socks, ratty tee shirt with stretched out neck, and the dogged determination that has carried him more than 80,000 miles since we’ve known each other. Photo © Sports Photos, Coronado, CA

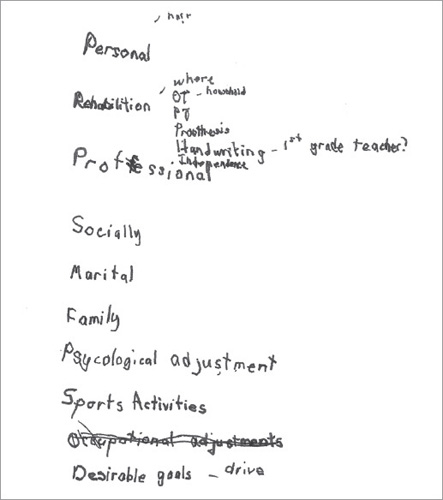

Reconnecting with my radiology colleagues, “Rad Gang,” at the White Memorial Medical Center six days after the accident. It was hard to spell correctly as I started writing with my left hand. Photo © Linda Olson

This is the list of priorities we made the first week. Dave made me record it so I could practice writing with my left hand. Photo © Linda Olson

The very lengthy and alliterative introduction to the “Report Card” created in the evenings by our families and friends after they’d had dinner . . . and perhaps a drink or two. Photo © Linda Olson

Using the alphabet to grade our condition in the hospital infused some crazy humor into everyone’s lives during those first three weeks. Photo © Linda Olson

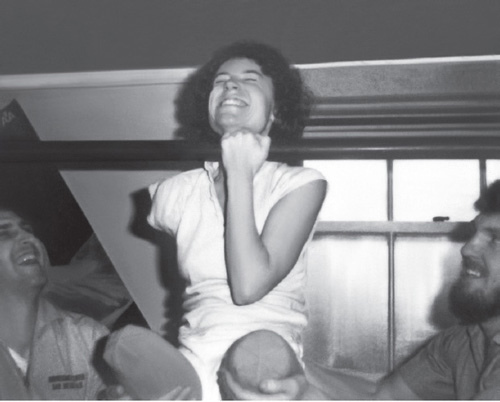

Learning how to do one-armed chin-ups in physical therapy with the help of two Navy techs. We always made it look like fun. Photo © Donna Pavlick

Dave and Donna Pavlick helping me stand in my first set of legs that looked like they’d come from a plumber’s supply store. The rigid sockets were strapped around my pelvis and attached to metal knees and pipes which were affixed to feet with non-articulating ankles. They were just about as comfortable as it sounds. Photo credit unknown

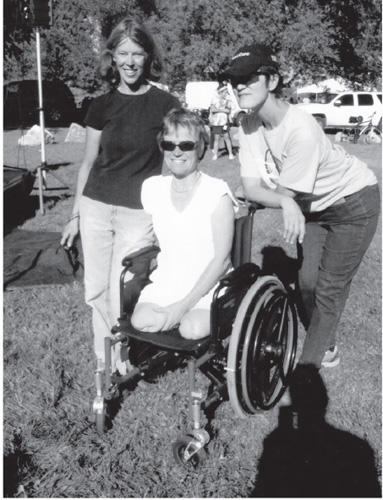

Resting after a walk with Donna at Mission Bay Park, the day before Tiffany was born. I kept those boots on my prostheses twenty-four hours a day-including during labor and delivery. Photo © Adrian Johnston

Dave holding Tiffany soon after she was born. Having children fulfilled a lifelong dream of his. Photo © Linda Olson

Linda and Tiffany. There was always at least one kid on my lap until they were three or four years old. Photo © David Hodgens

The beach north of Scripps Pier is where Dave took me in my bikini a couple of months after the accident and where we went with the kids once or twice a week as they were growing up. This was our home away from home. Photo © Linda Olson

Brian helping me cook. This is the part of the kitchen that we built at wheelchair height. It was also perfect for children. Photo © David Hodgens

First camping trip to Yellowstone Lake when Brian was 5 and Tiffany was 8 years old. This began our tradition of annual wilderness adventures with the Cox family. Photo © Linda Olson

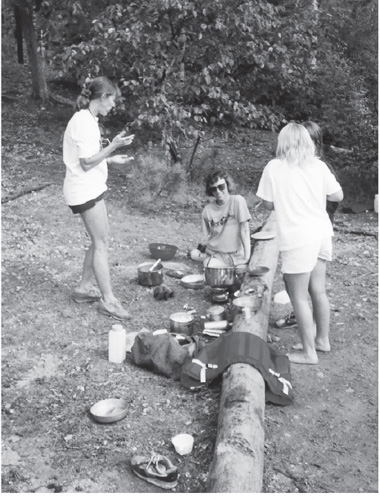

Carla, Heidi, Tiffany and I in our Yellowstone kitchen where my very important job was to boil water and cook on a tiny backpacking stove. And to ration the reward for paddling all day—M&M’s. Photo © David Hodgens

This serendipitous photo of my legs resting up against a tree in our camp in Yellowstone is one of my favorite pictures. It embodies my life after the accident; being able to adapt and get out and go with or without legs. Photo © Linda Olson

If you look carefully you can see my distinctive butt-walking tracks behind me in the sand making it pretty easy to tell where I’ve been. Photo © Trilby Cox

Brian and Tiffany grew up playing water polo at San Diego Shores with Doug Peabody and went on to play varsity water polo at University of California, Davis. This sport created a second family for them and helped define their lives even past college. Photo © Linda Olson

Dave has carried me many miles in backpacks like this that he modified with a drop-down shelf for me to sit on. People coming toward us thought he was a two-headed hiker. This was on the trail to Yosemite Falls with Half Dome in the background. Photo by an unknown hiker

Thanksgiving at Coronado when Tiffany was in college and Brian in high school. Photo © Janice Hauser

The middle-aged versions of me and my college roommates, Carla Wissner Cox and Juli Ling Miller. Along with their families, they’ve been the mainstays of our support team from the very beginning. Photo © David Hodgens

Yvonne Espinosa and Carla and Roger Cox accompanied us to Machu Picchu, one of the most amazing places we’ve been. Our guides, Edgar Mollinedo Quispe, Jose Ugarte de Souza, Benjamin Muniz Martinez, and Washington Gibaja Tapia carried me up and down the steep trails using the backpack Dave had made or pushing me in a wheelchair they’d made for me. Photo by an unknown hiker

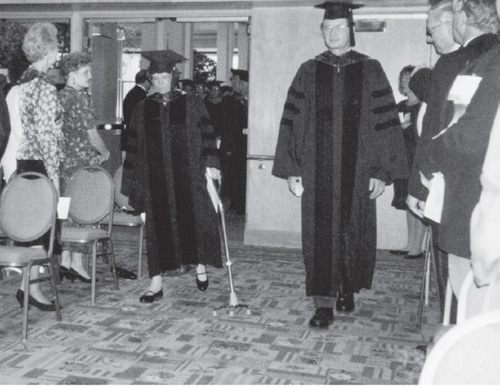

I was honored to become a Fellow of the American College of Radiology in 1993. This is one of the few pictures we have showing how I walked independently with a quad cane. Most people had no idea I was missing both my legs. Photo © David Hodgens

I interpreted thousands of mammograms at UCSD during my career. The perfect job for a one-arm radiologist. Photo © Haydee Ojeda

Life has come full circle. Our granddaughter, Sierra, sitting in my wheelchair and cooking with “No-Leg Grandma.” Photo © David Hodgens

It was hard to believe, but it was real. I’m going to be independent, living on my own again. And loving it! Who’d have thought that nylons, the bane of women’s existence, would be my ticket to freedom?

When we finished unpacking, Dave pushed me across the parking lot in my wheelchair, into the hospital, and down the hall to the back door of the radiology department. The big, automatic door-opener plate along the right side of the double doors meant one less obstacle in my world. I put on my happy face, ramped up my energy, pushed up out of my wheelchair, got my balance, and took hold of my quad cane. I took a deep breath and told myself to relax. This is going to take all the willpower you have.

As I walked down the long hallway, my perspective was very different. Walking required an enormous amount of energy but even more focus. I stayed near the right-side wall, pretending it would hold me up if I started to fall. My eyes were riveted to the linoleum, looking for slight irregularities so I wouldn’t lose my balance and bash my face on the floor. I was so focused that it was impossible to talk and walk at the same time.

“Dr. Olson, is that you?” I heard astonishment in the heavily accented voice of the man who had been the radiology film file room director for many years.

I finished the step I was taking and planted my feet and quad cane firmly, in as stable a stance as I could muster, before I looked up. Dario was a small, shy, older Filipino man who walked quickly, in a hunched-over, self-effacing fashion. He got close to me and stopped, recognizing how precarious I looked standing in the middle of the hall. Tears trickled down his cheeks.

“We are sooo happy to see you back. Please tell me if I can help you.” I let go of my cane and hugged him tightly.

I thump-thudded my way down the wide hallway, pausing at each room, thinking about the procedures we did in each one: sialograms, lymphangiograms, venograms, and hysterosalpingograms, upper GIs and barium enemas, bronchograms, and on and on. Radiologists perform all of these exams while standing in the room and insert catheters or needles for injecting contrast material so they can see an anatomical structure. We were just starting to do ultrasound studies. CT was not yet available at our hospital. Only two years earlier, in 1979, there were only two hundred CT scanners in the United States.

I was lucky to be near the end of my training. I already knew how to do all these procedures; now, I’d just learn how to do them in new ways. I thought I’d probably need to specialize—that is, not be a general radiologist. But that was okay with me. I hated doing invasive procedures like angiograms anyway.

Dave and I stayed just long enough to say hi to everyone and confirm to ourselves that I could truly get around the whole department by myself. No more guessing. It was going to work.

Late that evening, balancing with my cane, I walked Dave out to his car as he readied to drive home to San Diego. Leaning against the car for support, I hugged him. We held each other tightly for a long time, tears running down our cheeks.

“Sorry I’m crying,” I blubbered. “I’m really happy to be back. But it’s a little scary. I don’t want you to worry about me. I’m going to be just fine.” I accidentally bumped my cane, and it fell over. I leaned down and grabbed it, steadying myself against the car door. “Remember when you moved me up here the first time? I was scared then, too.” We were silent for a while. I remembered what it was like to stand there when I had feet that wiggled, bouncing from side to side with nervous energy. Feet that probably got cold standing there. Dave had supported me back then, just as he did again that night.

He hugged me even tighter. “Olsie, I know you can do it. And I know you need to do it. To be independent and finish your residency. You’ve worked really hard to get here tonight. I’m so proud of you.”

“Thank you,” I whispered, “for staying with me and helping me be strong. I don’t think I could have done it without you.”

He started the engine and switched on his headlights, watching to make sure my fake feet and cane got me safely back into my apartment. Then he was gone and I was on my own—again. We were regaining our independence. But it was different. We would be apart but closer than ever.

Dave and I resumed seeing each other only on weekends. Over the years, we’ve told our friends that it’s one of the reasons we’re still married—working hard during the week without each other and then playing together on the weekends. When I was on call, he drove up to see me. When I wasn’t on call, I rode the Amtrak train from Union Station to Del Mar, just as I had for the three years before the accident. On Friday evenings, I loaded my wheelchair and overnight bag into a taxi that dropped me off at the train station, where I waited at the main entrance for an electric cart. I was just able to sidle up to it, pull myself semi-gracefully onto the seat, and settle in for a sedate ride through the ornate, high-ceilinged station, with its mission revival, art deco, and Spanish colonial architectural design. The floor and walls of the cool, cavernous hall were lined with travertine, terra cotta tiles, and inlaid marble strips. Enormous wrought-iron chandeliers floated high above the massive space. It’s a recognizable setting that’s appeared in many movies, and it welcomed me every week.

As soon as we crossed from the fancy floor to the concrete passageways, I had to hang on as the driver mashed the pedal to the floor and careened around corners, zooming up and down the subterranean ramps en route to the designated train track. I was usually the only passenger, and the driver knew I wouldn’t complain about his speed-demon driving. Diesel-fuel fumes and the hiss and screech of nearby trains braking their way into the station assaulted my brain as the cart strained up the steep tunnel ramp and emerged onto the concrete platform.

Coasting to a stop at my train, I craned my neck, looking for my bevy of big black porters dressed in their navy-blue uniforms. They hovered over me as soon as I alighted from the cart, waiting to see if I needed help. The loud shushing, in-and-out breathing sound of the engine and wind blowing between the trains made walking with my cane an adventure. As I neared the huge metal wheels, I looked down between the edge of the concrete and train and saw the tracks and gravel rail bed.

I’d stared hard at the tracks the first few times I made this trek, challenging myself to see how I felt, to see if it would trigger any flashbacks or nightmares. Dave told me he did the same thing and had the exact same reaction—nothing.

We actually like riding trains. Being pragmatic people, we see them as a utilitarian means of transportation with multiple advantages over driving. No more traffic jams; easy to read or study for the two-and-a-half-hour trip or be lulled to sleep by the clickety-clacking tracks and gentle swaying rhythm of the car. And to feel refreshed at the other end, rather than angry, tired, nervous, or frazzled—what could be better?

“Hi, Doc, how ya doin’?” my favorite porter boomed. “It’s my turn this week.”

As soon as I got to the train steps, he leaned over and scooped me up in his big, strong arms while I crooked my left arm around his neck and broad shoulders. He swept me up the three or four steep steps into the train, whereupon he leaned over and gently lowered me inside the doorway. I left him with a hug, a thank-you, and a peck on the cheek. The porters all knew my story and appreciated that I had no fear of riding the trains with them every week. They knew I was pregnant and absolutely loved watching me glow and grow—being part of our family’s journey. Dave says I have a way of making men happy by letting them carry me. None of these men seemed the least bit fazed by the fact that I’d gone from a lightweight to 110 pounds.

Upon arrival in Del Mar, I strained to see Dave, who was always either standing on the platform or walking alongside the train and peering into the windows as it slowed to a stop. When he saw me, he bounded up the steps and swept me down and out into his waiting car. The crash of the surf a couple of hundred yards away and the salty sea air were the prelude to another weekend together, enjoying each other and our impending new life.

I was elated to be back at work, where my days became predictable: be at morning conference by 7:00 a.m., work from eight to five, get supper in the hospital cafeteria, roll across the parking lot in my one-arm-drive manual wheelchair to my apartment, study for two hours, and go to bed. My pregnancy gave me more focus than I’d ever shown in my life. Scared I’d flunk my oral boards, I mapped out a rigid study schedule. I was even more scared that the baby would be too small or abnormal somehow, so I ate healthy food and got lots of rest.

The staff and my fellow residents enthusiastically reintegrated me into the program, figuring out ways for me to perform procedures and operate the radiologic equipment. But, most of all, they fluttered around me as if they were an army of surrogate parents, attending to the needs of my unborn child. Having me back at work while I had a new life within me was the icing on the cake. It helped all of us believe that things might get back to normal after all.

By the end of the first week, there was one elephant in the room. My fellow residents had been covering for me by starting IVs on my patients who needed intravenous contrast for procedures, but we all knew that had to change soon. It would have been nice if radiology technologists could have done it, but the state of California did not allow them to do so at the time.

“Hey, Linda.”

I looked across the room to see Eric, one of my favorite techs, standing in the doorway. He held up a tourniquet and motioned me to follow him, which, like an idiot, I did. “Where are we going?” I asked when he turned left toward the hallway where all the radiologists’ offices were.

“Dr. Sanders and Dr. Woesner want to see you.”

Well, isn’t that nice.

When I reached Dr. Sanders’s office door, it seemed a little strange to see him sitting catty-corner at his desk, leaning over with his arm flat out in front of him. Dr. Sanders was a big man—six feet, five inches tall and weighing in at over two hundred pounds—who had a commanding presence and a booming, deep voice. I started to giggle when I saw him sprawled halfway across his huge mahogany desk, but the sight of Dr. Woesner pacing back and forth on the other side of the desk brought me back to my senses.

“You have to be able to start IVs, or you can’t be a radiologist,” Dr. Sanders said.

“I know, but I haven’t figured out how to do it yet.”

“Well, put your heart-shaped tush down in that chair and start by practicing on me.”

I grasped the armrest of the chair, hoping it was sturdy enough to withstand my sit-down assault, and plopped down. As they hit the wood chair, my prostheses made a loud clunk, another of my new signature noises.

“Eric,” Dr. Sanders said, “tie that tourniquet around my arm.”

In no time, a big vein popped up, just waiting to be punctured with the butterfly needle that appeared out of thin air. Dr. Sanders had with his other hand already cleansed his arm with an alcohol swab and was waving his hand over it to air-dry the skin so it wouldn’t sting when the needle entered it.

“I can’t do this to you,” I blurted out. “What if I miss?”

“And just who do you think is going to let you do this, other than me?” he demanded.

I’d worked there long enough to know I had no choice in the matter, so I picked up the needle and wiggled around in the chair so I could line up my hand somewhat parallel to the pipe of a vein in front of me. I started to close my eyes but then quickly opened them. I had to keep my eye on the needle as it went into the vein, or it might go through the other side and cause a big hematoma. A freaky quote from Dave popped into my brain and distracted me momentarily. To him, baseball is full of metaphors for life: Keep your eye on the ball, stupid! And, lo and behold, it worked. I looked up just in time to see Dr. Sanders open his eyes, and we all broke out laughing. Eric pulled off the tourniquet, and we high-fived all around.

Now, one successful venipuncture does not guarantee you can do it again, so when I got to San Diego for the weekend, Dave, with a box in his hand, confronted me.

“Look what I brought home for you,” he said, with love in his eyes.

To my dismay, Vampire Dave poured out at least a dozen butterfly needles, packaged alcohol swabs, and a beige tourniquet. What an awful way to spend the weekend.

“I can’t do this to you!”

“Yes, you can, and you will. We’re going to make sure you’re good at this before you go back to LA next week.”

I wanted to sit down and cry. He was right, though. The last thing I should be doing was practicing on patients who were sick and trusted me to take care of, not harm, them. So I rolled up to the kitchen table and locked my wheelchair.

“Okay, big boy. Let’s see what you’ve got,” I said. Dave made a fist and laid his arm out straight in front of me.

“When you get this side, then I want you to do the other arm,” he said.

By Sunday night, I was pretty good at starting IVs, thanks again to my husband, who loves me and will do anything for me.

“Dr. Olson, please go to Dr. Sanders’s office.” The overhead announcement echoed throughout the radiology department. This was a common occurrence that struck fear in the hearts of all residents. I trundled to the back hallway and walked in with trepidation.

“Yes? What did I do?” This was my standard response to the command.

“Put your heart-shaped tush in that chair over there.”

I let go of my cane and sat down. Dr. Sanders waited at his desk, twiddling something in his hands.

“When was your last menstrual period?”

“Pardon me? Why?”

“We need to figure out your exact due date to make sure it’s well before the dates for the boards in Louisville.”

Whew. I exhaled. No problem there. My due date was in early March, several months before the usual June exam dates. I’ll be svelte by then. None of those old geezer radiology examiners will know that I’m a new mom . . . and they’ll pass me with flying colors. I’ll soon be one of the boys, a board-certified radiologist.