A CITY AT WORK AND AT PLAY

“ Eating and sex: that’s human nature.”

—Mencius, 372 BC to 289 BC

For many ordinary Hong Kong people, buying and selling real estate at high speed is a sort of extra job. And flats sometimes change hands numerous times while they are just a twinkle in a property developer’s eye. A friend of mine bought an apartment in a new Hong Kong housing development. I congratulated him and asked, “What’s it like?”

“I don’t know,” he replied. “They won’t finish building it for at least a year.”

“Well at least it’ll be nice to be the first owner of a brand new property,” I offered.

“I’m not the first owner,” he replied. “I’m the fifth.”

This is a work-obsessed society, and making money from property—building it, investing in it, buying it, selling it and renovating it—is the single most popular field of endeavour.

Floating taxis and fishing vessels can still be found in Aberdeen Harbour, which is most famous for its floating restaurants and the boat people who live in its waters.

And it happens at speed. Even for apartments which actually exist, the market moves fast. I’ll never forget the day I decided to sell my apartment. At 4.30 p.m., I visited the property agent and told him I wanted to put it on the market. By 5 p.m., he had phoned a list of buyers who turned up at my front door and started bidding for it. By 6.30, I had the deposit in cash. True story.

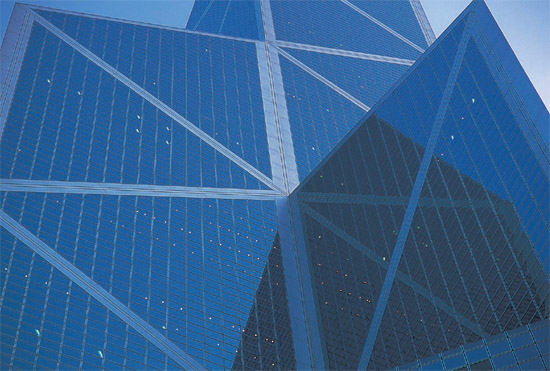

But does a strong economy make a paradise? No. Let’s put things in perspective. Even the most blindly over-enthusiastic Hong Kong booster (and I’m talking about myself again here) has to admit that the place has certain shortcomings. The one that amazes me is our stunning lack of creativity. Let’s examine this in conjunction with the property theme which we started this chapter with. We in this city are absolutely brilliant at producing buildings—but we are terrible at naming them, since that takes creativity. We can throw buildings up seemingly overnight. We can do skyscrapers, we can do groundscrapers, we can do round buildings, square ones, triangular-shaped ones and ones with lots of eye-catching geometric angles—as the incredible pictures on the following pages show. I know of cases where we have erected tall towers, decided we didn’t like them, and then tore them down to start again—all before a single human being had spent a single night in them. We produce buildings so fast that when a block reaches the age of 30, banks stop offering home-loans on it, since everyone assumes that it is time to knock it down and replace it with a fresh one.

But when it comes to naming them—ah, well, that’s different. Naming a building takes creativity. You can’t do it out of an engineering manual. It takes poetry. It takes an artistic soul. We are not at all good at that kind of stuff, sorry. Failing to understand the creative principles involved in naming things, we instead use labels. The central business district used to be called Victoria; now it is called Central. At the middle of Central is a building called Central Building. Nearby is a tower called Central Tower. Down the road is a commercial building called Commercial Building. In the suburbs, we find a building called Skyscraper, and on the other side of the harbour is a Multi-Storey Car Park Building called just that. Near where I live, there’s a hospital. The main block is called Main Block. Recently they built a new clinical wing, named New Clinical Wing. You get the point.

Occasionally, we work up a bit of courage and add an adjective to our building names. For example, there’s a Newish Building and an Adjoining Building in Hong Kong. Near my old office there is a restaurant called Quite Good Chinese Restaurant (its signature dish is Quite Good Noodles). But my favourite restaurant is gone now. It used to be in Wellington Street, in Central: a wonderful vegetarian restaurant, called, you guessed it, Vegetarian Restaurant. The waitresses inside all wore name badges; and every badge said: “Waitress,” thus serving to differentiate the young women from the plants and the fish.

No; poetry is not our thing. We are practical, working men and women. We work on the land, we work on the hills, we work on the waters of the harbour, we work from barrows and cardboard boxes on the pavements.

Water is never far away for Hong Kongers, who love messing about in boats.

To a photographer with a sharp eye, and advanced mountaineering skills, the striking geometric shapes of the best of Hong Kong architecture become evident.

Architect I.M. Pei dared to build the Bank of China out of triangles, which are beautiful but violently upset feng shui fans

Sometimes the old ways still work the best, this woman keeping cool with a fan seems to be saying.

But we don’t spend all our time making money. We also spend a great deal of time spending it. Shopping is Hong Kong’s Olympic specialty. People in our community have developed our own form of aerobic exercise to get a workout: speed shopping.

The range of options for the shopping addict is immense, with whole areas devoted to single products—either popular items, or even quite esoteric, niche items. Happy Valley has a whole street of shops selling high-heeled shoes and designer boots, and Wan Chai has a road lined with chandelier stores (why not pick up a few on your way back to the hotel?). For something more exotic, check out Sheung Wan, located a short walk east of Central. It is filled with shop after shop where ancient, sun-dried, strange-smelling fish are sold by ancient, sun-dried, strange-smelling fishmongers. How they all compete with each other, I have no idea. It is like stepping back in time to old China—and it becomes even more curious when you realise that this area is listed on old maps as “Chinatown.” Yes, even a city in China can have a Chinatown.

We also have shops for dead people. You find them also in Sheung Wan, after the dried fish stores. These “dead” shops sell items fashioned in paper and card, designed to be burned and thus sent to heaven, for the use of the recently departed. (Once burned, they are assumed to re-appear in heaven as solid, useable items.) The range of paper-made goods destined to rematerialise in paradise is amazing. There are designer shirts, sports cars, televisions and houses. There are paper servants. There are airline tickets, although I’m not sure what they are for (are dead people allowed to fly back to earth for their holidays?). There are computers, so watch out for emails from dearly departed Third Uncle Pang. And the really bad news: there are recent model mobile phones, and karaoke machines with extra large speakers. The noise pollution in the Hong Kong equivalent of heaven is going to be pretty bad.

Niche shops in Hong Kong are fun, but at the other extreme of the retail scale, we have the super-malls: citadels of spending, where the world’s most expensive designer labels pay astronomical rents so that tycoons can spend astronomical sums on handbags and scarves. Let them, that’s what I say. It puts money into the economy that may trickle down to the rest of us. These places operate entirely under their own surreal rules of rationality. I once received an invitation that said: “Welcome to the first Hermes leather exhibition. Stand in awe beside the giant-size Kelly bag.”

The mores of the upper end of Hong Kong society have to be seen to be believed. I recall an incident when a woman had a coughing fit in the upper crustacean cake shop at the Mandarin Oriental hotel. She could barely catch her breath but managed to gasp one desperate word: “Water!” Came the reply from the staff: “Evian or Perrier?”

What else do people in Hong Kong do for work? Well, we used to make things. But we’ve moved from manufacturing to being a service centre. These days, we don’t actually make stuff, but we sort of pretend to. Or to put it another way, we collect advance orders for things from buyers all over the world, and then we pay people in mainland China to actually make it. We have become the middlemen and we seem to be pretty good at it.

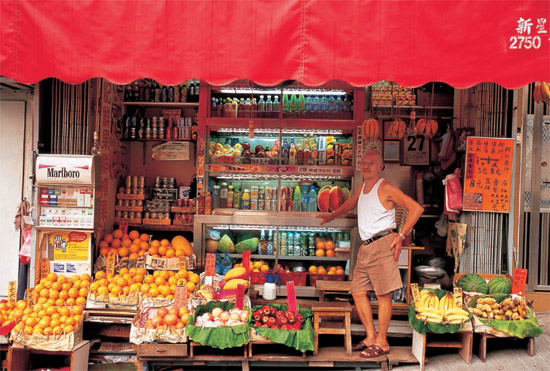

The standard technique when space is at a premium—use every centimetre and turn your shop into Aladdin’s cave.

In places such as Aberdeen, Causeway Bay and Cheung Chau, clusters of wooden boats can be found—useful since Hong Kong has more than 230 islands.

There are still floating houseboats in existence, where families live, and children are born and brought up—but these days, they rarely decide to spend their lives afloat.

To add a touch of greenery to the new outlying islands ferry terminal, a green lawn and flowerbeds were added—plus a raised walkway to prevent people actually stepping on any of it.

A glorious multihued hanging sculpture contrasts with the angular lines and classy colourlessness of the International Financial Centre complex

Pavement cafes, called dai pai dongs, often serve simple tasty food, sometimes without bugs.

Take toys for example. Think of Barbie dolls, Snoopy merchandise and Ninja Turtles action figures: they’re American, right? No. They’re made in factories managed by Hong Kong business people in mainland China. Think of Pokemon figurines and Sony gadgets: they come from Japan, right? No. They’re also made in factories managed by Hong Kong business people in mainland China.

In fact, a huge percentage of the sort of things that people give to each other at Christmas—toys, watches, gadgets, general gift items, T-shirts—are made by companies run by Hong Kongers. This city also has a massive amount of the market for fake Christmas trees around the world. That makes me so proud.

We really are the toy kings of the world. We respect toys around here. Only in Hong Kong can an adult man impress an adult woman by telling her that he has a complete collection of Hello Kitty plush dolls. There’s no shame in enjoying toys at any age here. The 50-year-old bus driver who takes me to work has Winnie the Pooh collectibles all over his dashboard as he hurtles down the highway, cursing and swearing at everyone else on the road.

I always think it is ironic how Christmas movies inevitably propagate the myth that Christmas gifts are made by thousands of elves in busy factories at the North Pole. Well, they are indeed made by thousands of small people in busy factories, but there is little similarity between the North Pole and the factory townships of Guangdong.

For this reason, true Hong Kongers make it a point never to complain about the commerciality of Christmas. It is a significant factor that puts the rice in our rice bowls.

Ours is a relatively small community, but in terms of international business, our batting average is high. One of the reasons for this is that we are extremely good salespeople. If anyone doubts the truth of this claim, I can simply refer them to the time when a Hong Kong man managed to sell a homebuyer an apartment on the 25th floor of a 21-storey building. It’s true: it was in all the newspapers.

Of course, life in Hong Kong is not all about work. One has to relax as well. Eating is one of the big hobbies in this city. We like to eat well. My workmates like to order giant doughsticks deep fried in peanut oil, accompanied by Peking Duck with extra fat, followed by sticky rice and mango pudding, and all washed down with a Coke—Diet Coke only, please. You have to watch those calories, you know.

It is hard to over-emphasise the importance of food in Hong Kong. When a bakery chain closed down a few years ago, customers rioted outside branches. Why? They explained that they had been holding that chain’s cake vouchers for years “as a form of investment.”

Food is also big business in Hong Kong, and people with a talent for free enterprise can make a fortune. It is really true here that one man’s rubbish is another man’s delicacy. A case in point: in supermarkets around the territory you can buy, for the equivalent of US$ 2.50, a bag of “Old Orange Peel.”

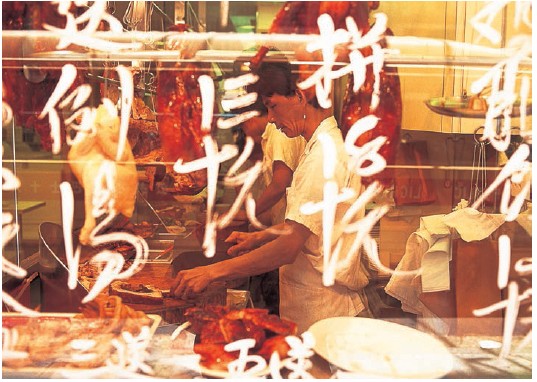

The many shops specialising in fragrant barbecued meats are a carnivore’s paradise.

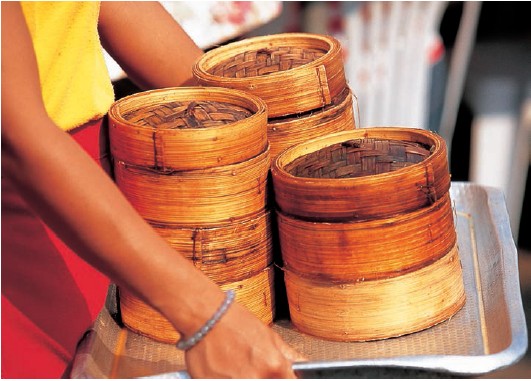

Dim sum is still served in bamboo steamers that retain the heat and ensure customers enjoy a hot meal.

Fire trucks explode out of these doors, so one hopes this dear old lady in traditional padded jacket and pajama-style trousers can move rather fast.

Food is funny here. I’m not sure why: it just is. I love to collect menus and signs from Hong Kong restaurants, such as the notice displayed on the door of a restaurant in Causeway Bay: “All vegetarians digested here.”

And then there are the items you find on the actual menus:

Chicken and string bean with strange sauce

Dehydrated pig

Welsh ham from Scotland

And so on. I could go on for hours about items I have found on Hong Kong menus. Carp fish is sometimes served, and often misspelled. For some reason, it usually becomes “Crap in brown sauce.” Not an enticing dish for a place famed for the quality of its cuisine.

The entrepreneurialism that is such a classic Hong Kong trait can often be seen in the catering business. A businessman friend, lazing about in his yacht off the coast of Middle Island, south of Hong Kong island, suddenly got a craving for pizza. He decided to phone the local pizza shop to see if one could be delivered to him. Half an hour later, a sampan bobbed up next to his yacht, and a pizza boy delivered the goods. Where there’s money to be made, someone here will find a way to make it.

That’s one area where we never lack creativity.

In the sweltering weather, it’s no surprise that Hong Kong is one of the world’s biggest per capita consumers of oranges.