THE CITY OF LIGHTS

“ As soon as you have made a thought, laugh at it.”

—Lao-Tzu 604 BC to 531 BC

It was not a dark and stormy night. It is never a dark and stormy night. Such things are unknown in Hong Kong. We never get true, jet-black darkness here. After dusk, the sky over the city becomes a huge, opaque, shifting, gray ghost. Only the brightest stars can be seen. (We’re very discriminating in that way.)

Let’s face it, our home is nothing less than one of the world’s biggest tributes to Thomas Edison. If the inventor of the light bulb were brought back to life and shown this place, he would surely be astonished, and would race to tell the Edison descendents to flood the city with billions of claims for residual royalties.

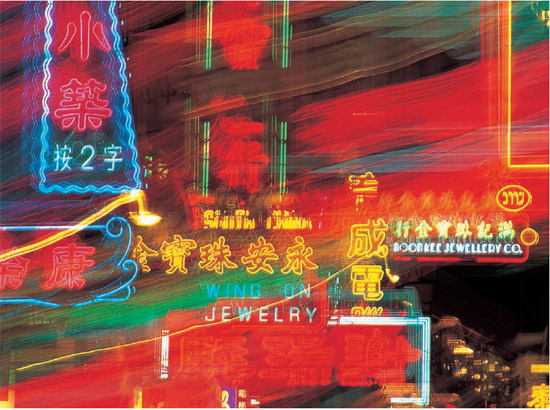

The lights shine brightly here, and there are lots of them. With many of the residents coming from rural China or elsewhere in Asia, electric lights are still something to celebrate, and we’re delighted that neon blinks at us from every downtown corner.

The poky boxes in which we live are much cheered by the rainbow of lights that flicker into them. I lived in one flat in which the neon-lit Chinese character pronounced “On” (from the department store Wing On) blazed into my front room. The character meant peace and our feng shui master saw it as a highly positive sign.

I recall many years ago walking down Nathan Road, a glittering neon-lit commercial thoroughfare in Kowloon, and wondering aloud to a knowledgeable friend: “Wouldn’t it be incredible to own all the electricity in Hong Kong?”

“Actually, someone does,” my friend replied. “His office is right there.” He pointed to a building on the east side of the road.

It was an exaggeration, but not much of one. The electricity in Hong Kong is not owned by one person; it is owned by two. Utilities are not state enterprises in the city; power is provided by two commercial companies, the principals of which are very wealthy indeed.

Yet in terms of rainbow-coloured eye-hurting super-cities, Hong Kong still lags far behind the kings of the genre, such as Las Vegas, or downtown Tokyo. There’s a good reason for this. For much of Hong Kong’s history, the main air strip was at Kai Tak, a piece of land bordering one of the most densely packed residential areas in the world. Descending aircraft used to skim so close to Kowloon City that air travellers could actually look through people’s windows and see what they were having for dinner—this is not a joke!

This wonderful shot captures the elemental nature of Hong Kong—surging sea, soaring mountains, and glittering human infrastructure which mixes Chinese and Western influences.

A nebula of fallen stars. It’s hard to believe that glassy, glittering Hong Kong was described by its first British masters as “a barren rock.” Most harbour-side buildings stand on reclaimed land, alongside a harbour that today is half its original width.

From the plane’s portholes, you could see the traffic lights on the road and could not help but wonder whether the pilot would stop for them.

To reach the runway at the correct angle, aircraft had to fly so low that buildings throughout the city were banned from having lights which flashed, throbbed or were animated in any way. Buildings in Kowloon had an even stricter set of rules, with no structure allowed to rise more than 12 storeys, and no light shows at all allowed near the airport.

Kai Tak airport was closed down in the summer of 1998, and Hong Kongers, without waiting for the laws to be updated, started a frenzied programme of adding flashing lights, moving colours, and animated words and images to their buildings. The authorities joined in, and “shows” made up of computer co-ordinated blasts of multi-coloured light shining from rooftops are common these days.

Talking of night-time light shows, fireworks (vividly known as “flame-flowers” in Chinese) on the largest scale are wildly popular here. Major corporations scramble to outbid each other for the right to pay for the major fireworks extravaganzas, the biggest being the one that ushers in the Lunar New Year every spring. The two harbour-sides form natural viewing areas for the flame-flower shows, which use the water, and the air directly above it, as the catwalk on which they can strut their stuff. It’s almost a theatre-in-the-round.

Garish but well-loved, “The Jumbo” is a surreal, floating neon-outlined restaurant in a dark backwater; it sears itself into memory.

Hong Kong and neon were made for each other; they’ve started a love affair that shines through every window and illuminates our comings and goings with Hollywood-style mood lighting.

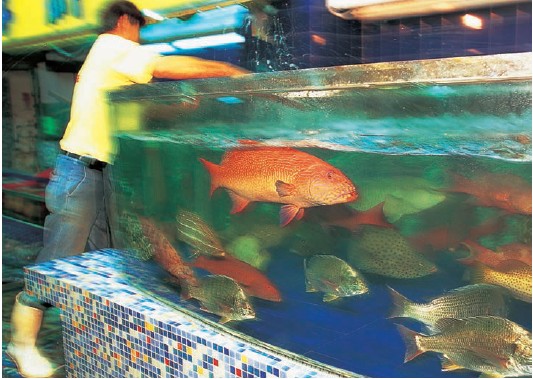

Eating out is an addiction in Hong Kong and with an estimated 10,000 restaurants to choose from, diners are spoilt for choice.

To perceive the magic of light in the same way as Hong Kongers do, plan an evening as follows. Wait until dusk, when the sun is just slipping into its watery bed in the South China Sea and the clouds hanging over the horizon are turning pink. Get yourself to the Aberdeen harbour, on the south side of Hong Kong island. Stand on the shore until you are approached by a water taxi. A gorgeous, toothless old lady will drive you in a small, motorised junk through the moored fishing boats of Aberdeen harbour, some of which are still used as homes for families who grow up on the water. Then, as darkness falls (okay, as grayness falls), your little vessel will carve a channel through darkening waters under a high bridge until it comes upon the Jumbo Floating Restaurant. This is a grotesque, garish palace of a restaurant, wildly tacky and supremely beautiful at the same time, with its multi-storey outline picked out in a riot of rainbow-neon lines. There are a few restaurants there—but it is hard for the chefs to make a meal as memorable as the journey to the eatery.

To some extent, people in this city love the light too much. They have lost the circadian rhythms of day and night, and it is not unusual to see families, and even small children, out and about in the middle of the night. Individuals do not rest their eyes enough, and the majority of the population needs artificial eyesight correction.

And for amateur and professional astronomers, the loss of the night sky is a tragedy. Can one ever escape from the light, to see the stars? Yes, but only by travelling to the rural edges near the city borders, to places classified by locals as “beyond the red taxi borders.” (Hong Kongers measure distances in terms of taxi livery. If you travel within the main urban centre, your taxis will be red. Go further from town and the livery changes to green. And travel still further, onto one of the bridges that takes you to the island of Lantau, and the cabs become sky blue. Incidentally, Hong Kong’s hugely successful cab fleet owes its existence to young entrepreneurs from the mainland—especially the former “Prince of Taxis” Wu Chung, whose name is celebrated by being attached to the front of Wu Chung House, a skyscraper erected by his son Gordon Wu, a builder.)

True to its history as a fishing enclave, Hong Kong’s restaurants have seafood to die for—most of which is alive, and will shortly die for you.

The bizarre headquarters of HSBC, with its exo-skeleton on the outside, has become an ugly-beautiful icon of the business district.

But going back to the theme of lights, Hong Kong existed as a partially inhabited settlement long before it was officially founded as an independent enclave by the British in 1841. But it is not mentioned very often in ancient Chinese documents. Yet there is one reference, in a paper written many hundreds of years ago, that sticks in my mind. A mystic poet, writing about the area, prophesied that “a city of stars” would one day arise on that spot.

If you are lucky enough to have a window seat on an aircraft landing in Hong Kong on a clear evening, you will see a glittering constellation of glowing, twinkling, gold-and-blue pinpricks below you. It really is an absolutely breathtaking sight. And you will shake your head in wonder as I did, and realise that the ancient poet really did have an accurate vision of the future.

At night, the water of Victoria Harbour turns glossy black, reflecting the rainbow of neon lights from waterfront buildings.