1 Introduction

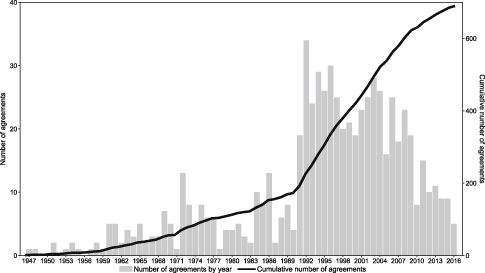

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is on life support. Its continued relevance has come into question as the Doha Development Round has staggered through nearly two decades of unsuccessful negotiations. The WTO’s 164 member states have been unable to reach agreement on core trade issues such as non-agricultural market access and agricultural subsidy reform. Despite the ailing WTO, countries are still actively pursuing international trade liberalization. Increasingly, they are turning to preferential trade agreements (PTAs) between smaller groups of countries, often just two, as an alternative to the stagnant multilateral process.1 Indeed, PTA numbers have been exploding in recent years, creating a massive network of overlapping rules and norms in what economist Jagdish Bhagwati has famously termed the “spaghetti bowl” phenomenon (Bhagwati 1995a). Figure 1.1 below shows that over 688 PTAs were concluded globally between 1947 and 2016, with 87 of these PTAs agreed after the WTO Ministerial meeting collapsed in 2008.2

In parallel to this explosion of PTAs, skepticism has also increased regarding the feasibility and efficacy of environmental treaties to solve global environmental problems. Despite an impressive level of international cooperation on these issues, with over 1,200 environmental treaties currently in force, environmental problems continue to worsen (Mitchell 2018; UNEP 2012). One explanation for this lack of progress is that global environmental governance operates on the basis of consensus. In trying to bring all countries on board, a consensus-based approach often results in lowest-common-denominator agreements that do little to actually solve environmental problems (Susskind and Ali 2015). Another explanation is that global environmental governance is weak because it lacks enforcement power. This deficit can, among other things, create incentives for some countries to free ride on the actions taken by others (Chasek, Downie, and Brown 2018). This has catalyzed interest in alternative options to protect the global environment. In particular, there has been a recent resurgence of interest in using trade agreements, and their relatively stronger enforcement mechanisms, as tools for environmental protection.

Growth of PTAs over time

Attempts to link trade and environmental policies are not new. Environmentalists have long attempted to leverage the economic benefits of liberalized trade (e.g., lower tariffs and increased market access) for more effective environmental governance. For example, environmental organizations have lobbied WTO member states to legalize the use of tariffs on products whose manufacturing process is deemed harmful to the environment.3 The WTO agreements also contain environmental provisions providing for exceptions to trade rules under certain circumstances. WTO members can implement environmental policies that would otherwise conflict with their obligations under WTO agreements if they are related to the conservation of natural resources or are necessary for the protection of human, animal, or plant life or health. Although these exceptions sound permissive, they have historically been interpreted quite narrowly, often hinging on whether the environmental policy was applied in a manner that constitutes arbitrary or unjustified discrimination.4 More recent developments at the intersection of trade and environmental governance are tethering these two domains even more closely and in new and innovative ways. This book explores this largely uncharted terrain of trade-environment linkages in PTAs.

PTAs are at the forefront of this innovation. Our analysis of 688 global PTAs reveals that about 86 percent of all PTAs globally now incorporate environmental provisions. Some of them are only vague references to the goal of reaching sustainable development, or are exceptions similar to the ones found in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) of 1947. But many other provisions are more far-reaching than those pursued in the WTO context. Since at least the mid-1980s, many PTAs globally have included not only the WTO’s environmental exemptions but also provisions requiring, for example, that trading partners implement multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs); cooperate on environmental issues; strengthen and/or enforce existing environmental laws; protect endangered species; regulate fishing activities; and address climate change. Importantly, as we discuss in chapters 2 and 4, some of these environmental provisions enjoy the full range of remedies available under the PTA’s dispute-settlement procedures. This level of enforceability for international environmental policy includes access to sanctions, and is thus far stronger than anything available under contemporary environmental treaties.

The United States has long been at the vanguard of these efforts. On September 15, 1992, William Reilly, then administrator of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), testified before the House Ways and Means Committee about the recently concluded North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). He confidently predicted to the House Representatives that, “for some time to come, when other nations negotiate with their neighbors to open up markets, NAFTA will be their model for dealing with related environmental issues” (Ludwiszewski 1993, 706). Reilly’s prediction was overconfident. NAFTA has never been a static model, even for subsequent US PTAs. However, he was certainly right to think that NAFTA’s environmental provisions would have a profound impact on the entire trade governance system, as they have since diffused into dozens of PTAs beyond the United States, providing a foundation for what have become some of the most far-reaching environmental provisions in trade agreements globally.

Growth of environmental provisions in global PTAs over time

Indeed, the United States is a global leader in terms of linking environmental and trade policies through PTAs. By “global leader,” we mean a country that is a pioneer and moves forward before other countries, that takes on commitments that go beyond other countries, and that generates momentum and incentives for other countries to follow suit (Young 1991; Skodvin and Andresen 2006; Chasek 2007). To be sure, the United States is a laggard on a number of environmental issues, most notably climate change (Andresen and Agrawala 2002; Parker and Karlsson 2018). In recent decades, the European Union is frequently presented as a global leader on environmental policies, at least in regard to climate change (Vogler and Stephan 2007; Kelemen and Vogel 2010). However, the role of the United States on the trade and environment linkage is clearly one of leadership.

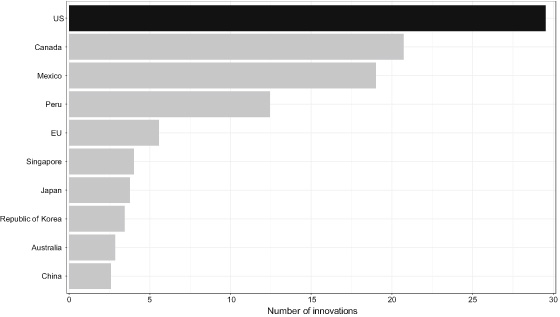

Indeed, the United States has been a front-runner in terms of substance, number of these provisions in its agreements, and influence over the global trade system. On substance, the United States is the most innovative country in designing environmental provisions in trade agreements, when calculated by the number of new environmental provisions included in its PTAs (Morin, Pauwelyn, and Hollway 2017). Figure 1.3 shows the most innovative countries as measured by the number of environmental provisions that were unprecedented at the time of their introduction in a PTA. We first calculate the number of innovations for each PTA and then divide these innovations equally among contracting parties of these agreements. When innovation is measured this way, the most innovative PTA ever concluded is by far NAFTA, followed by the US-Peru agreement. In fact, NAFTA and US-Peru are so innovative compared to other PTAs that they bring Mexico, Canada, and Peru up to the second, third, and fourth ranks of innovative countries, even if other Canadian, Mexican, and Peruvian PTAs do not include many unprecedented environmental provisions.

Total number of innovations per country (innovations per PTA divided by number of contracting parties)

For example, as we detail in chapter 4, the United States was the first country to make environmental provisions fully enforceable in its PTA with Peru, and it was a pioneer in linking PTA compliance to that of various MEAs, such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Indeed, some US PTAs lead the world in terms of the sheer number of environmental provisions they contain. The United States has included more than 100 environmental provisions in some of its recent PTAs and, as figure 1.4 indicates, on average has far more environmental provisions per trade agreement than do other major players in the global trade regime, such as the European Union, Japan, and China (the lines represent median values).5

Number of environmental provisions in US, Japanese, Chinese, and European PTAs (1946–2016)

The United States has also had prolific influence on trade-environment politics internationally, with much replication of US provisions across global agreements. Further, even as the Trump administration has retracted US engagement in international trade policy, the United States continues to influence how many other countries approach trade-environment linkages. This is nowhere more evident than in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Although the Trump administration withdrew the United States from the TPP in 2017, many of the TPP’s environmental provisions remain in the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) among the remaining 11 TPP countries.6 As such, recent estimates that 90 percent of the TPP’s environment chapter was derived from prior US PTAs reflect US influence on the CPTPP as well (Morin and Beaumier 2016). We discuss this global influence in more detail in chapters 5 and 6.

Therefore, in the WTO’s shadow, as more and more countries are turning to PTAs, the United States has increasingly incorporated innovative environmental provisions into these bilateral and regional agreements. This raises a host of questions related to the politics surrounding these trade-environment linkages. For example, we know little about the factors that enable and constrain how the United States identifies environmental issues through trade agreements, the character and extent of environmental provisions included in US trade agreements, the way US PTA environmental norms and policies impact domestic and international policy making in trading partner nations, or the impact of PTAs on MEAs’ implementation and effectiveness. These questions are at the heart of this book.

Centrally, this book asks: what are the impacts of the environmental provisions in US PTAs on environmental policy in trading partner nations and on the effectiveness of MEAs? We illuminate answers to these questions through a series of case studies. We argue that US trade agreements serve as mechanisms to diffuse environmental policies and norms to both trading partner nations and third-party countries. Further, we argue that environmental provisions in US PTAs can play an important role in enhancing the effectiveness of MEAs by strengthening the enforcement capacity of the latter through linkages to PTA dispute-settlement systems.

The next section briefly summarizes the history of global trade-environment politics, primarily focusing on the WTO’s activities in this area. This is followed by an overview of the scholarly literature, which emerged in response to those historical developments, and positions this book within that literature. We then explain our methodological approach to answering these questions before providing a detailed roadmap for the book, which also summarizes the book’s main findings.

A Brief History of Global Trade-Environment Politics

Despite some half-hearted efforts to develop so-called “win-win” scenarios, trade and environmental issues have historically been viewed in opposition to one another. At the core of this understanding is the idea that increased trade necessarily means increased production and consumption, which in turn means increased resource use and environmental degradation. Balancing this environmental reality is the trade community’s concern that environmental policies will be used as a form of protectionism. For example, domestic subsidies for development of solar panels could be used to protect fledging domestic industries by making foreign imports of such products less competitive in the market. In chapter 3, we map the literature on linkage politics and, in particular, that on why states choose to link trade and environmental issues. In this section and the next, we cover the empirical history between these two topics in contemporary policy and law, as well as the literature that has grown out of that linkage.

Daniel Esty’s foundational book, Greening the GATT, captures this opposition well in describing these issues as a clash of cultures, paradigms, and judgments between “free traders” and environmentalists, who tend to approach governance issues quite differently (1994). The “free trader” ideal type is more outcome-oriented, utilitarian, sees solutions as rooted in proper economic pricing, and tends to see environmental problems as indeed solvable. The environmentalist on the other hand, is more process oriented, concerned with moral imperatives, sees solutions as based in law, and tends to see environmental problems as far more severe. As Esty aptly quips, “the word ‘protection’ warms the hearts of environmentalists, but sends chills down the spines of free traders” (1994, 36). This dichotomy is clearly a simplification and has evolved substantially over time, especially with, for example, the growth of market mechanisms (e.g., emissions trading, carbon taxes) being used for environmental protection. Recent survey-based empirical studies have demonstrated, for example, that those who are more concerned with the environment also favor more protectionist trade policies, due to their concerns about trade impacts on the environment (Bechtel, Bernauer, and Meyer 2012). Further, despite political leaders in the Global South opposing linkages between trade and environment, recent empirical studies show this feeling is not shared by citizens. Namely, Bernauer and Nguyen (2015) find that citizens in the Global South do not view economic integration and environmental protection as a trade-off. Nonetheless, even if they are more simple than contemporary politics fully supports, the motivations undergirding Esty’s ideal types are still helpful in understanding the underlying politics at the heart of trade-environment issues in politics today.

Contemporary trade-environment politics can be traced back to the famous “tuna/dolphin” dispute (Kulovesi 2011). In 1991, a panel under the 1947 GATT upheld Mexico’s challenge to a provision of the US Marine Mammal Protection Act. The provision prohibited the import of yellow fin tuna from the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean if that tuna was caught using commercial fishing technologies, which result in the incidental killing of dolphins. The GATT panel’s decision in the “tuna/dolphin” dispute was never formally adopted. However, the case sparked much controversy and discussion, including by putting pressure on newly elected US President Bill Clinton to include environmental provisions in NAFTA, which was recently agreed under his predecessor, George H.W. Bush, but had not yet passed through the US Congress when Clinton took office (Houseman and Orbuch 1993). Clinton was ultimately successful in negotiating an environmental “side agreement” to NAFTA, officially called the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC). The NAAEC greatly expanded NAFTA’s environmental provisions over the WTO’s status quo. For example, the NAAEC created a citizen enforcement mechanism that allowed citizens to hold their governments to account if they were not enforcing existing environmental laws. NAFTA’s environmental provisions, though critiqued strongly by groups on both sides of the issue, opened the door for what would become a long history of environmental linkages in PTAs. We discuss the NAAEC’s provisions in more detail in chapter 4.

It is worth noting here, however, that NAFTA also included an investor-state dispute settlement mechanism that had important implications for environmental politics. This mechanism has been heavily critiqued by environmentalists and others, who argue that allowing foreign investors to sue governments if domestic (environmental) policies hinder their investments is a significant threat to environmental sovereignty (Neumayer 2017). Indeed, at least 18 disputes have been heard under this mechanism that have directly challenged environmental protection measures.7

Shortly after NAFTA entered into force, the WTO was created to succeed the 1947 GATT. The WTO adopted many aspects of the 1947 GATT, including its environmental exemptions (contained in GATT Art. XX). Importantly, however, the WTO framework made GATT rules, including environmental exemptions, fully enforceable. No longer would both parties to a dispute have to agree to adopt a panel’s decision; decisions were now adopted automatically and an appeals process was put in place. Moreover, panel and appellate body decisions could include sanctions or other retaliatory measures for violations of WTO rules. This new enforceability within the WTO dispute-settlement process drew additional attention to the WTO’s decisions surrounding environmental provisions.

Particularly important to the trajectory of trade-environment politics was the 1998 “shrimp-turtle” dispute, wherein Malaysia, Thailand, India, and Pakistan challenged US domestic policies that were designed to protect sea turtles from being inadvertently killed in the drift nets commonly used in commercial fishing operations. Despite US claims that the environmental policy was permissible under the WTO’s environmental exemptions (GATT Art. XX), the WTO dispute-settlement body ruled against the United States in this dispute. This triggered outrage in the environmental activist community, who saw this as the WTO again striking down domestic environmental laws. The most public manifestation of this outrage was the so-called “Battle in Seattle,” wherein upwards of 40,000 environmental and pro-labor activists joined forces to shut down the 1999 WTO Ministerial meeting with large-scale street protests (Seattle Police Department 1999). The media was flooded with images of activists in sea turtle costumes carrying signs that read “Teamsters and Turtles—Together at Last!” and chanting “We don’t want you! We didn’t elect you! And we don’t want your rules!” (Cooper 1999).

Environmental protesters in sea turtle costumes at the 1999 WTO Ministerial Conference

Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WTO_protestors,_1999_(20680767813).jpg#/media/File:WTO_protestors,_1999_(20680767813).jpg.

The WTO has since heard several environment-related disputes on issues ranging from gasoline to retreated tires to asbestos. Of central importance in these disputes is whether or not a specific domestic environmental policy that would otherwise violate WTO rules qualifies for an environmental exemption. These exemptions require that the domestic measure either “relate to the conservation of a nature resource” (GATT Art. XX(b)), or “is necessary for the protection of human, animal, or plant life or health” (GATT Art. XX(g)). If either of these conditions is met, it further requires that the policy was “applied in a way that does not constitute arbitrary or unjustified discrimination” (GATT Art. XX chapeau). As of the most recent WTO Secretariat summary report of WTO cases, the WTO has heard nine such disputes to date (WTO Secretariat 2019). Of these nine disputes, the WTO has ruled more often than not that a domestic environmental policy did indeed meet the requirements of Article XX(b) or (g). Nonetheless, the WTO has only granted an environmental exception once in a new dispute. This is because it has otherwise ruled that the domestic environmental policies in question did not meet the requirements of the Article XX chapeau. There has been one additional instance of an environmental exemption being granted. However, this involved a challenge to a party’s compliance with a previous decision. As such, in that instance, the WTO appellate body told the United States what to do to comply, and the United States followed those instructions to the appellate body’s satisfaction. Table 1.1 summarizes the Article XX disputes heard under the WTO since its inception in 1995.8,9

The most recent decision, adopted on January 11, 2019, after more than a decade of consultations, panel hearings, and appeals, was the US-Tuna II (Art. 21.5) dispute, in which Mexico challenged US policies related to the use of the “dolphin-safe” label. Both sides have won battles along the way, with, for example, a US win in a late 2017 ruling that US “dolphin-safe” labeling policy had been amended in such a way as to now qualify for an environmental exception. Although Mexico appealed this decision on December 1, 2017, on December 14, 2018, the appellate body issued its decision upholding the panel’s 2017 assessment.

In the last decade, the focus of environment-related dispute settlement at the WTO has moved away from Article XX exemptions. Rather, disputes have surrounded issues related to subsidies for renewable energy technologies. Eight such disputes have been heard since 2012.10 For example, in 2013, the United States (later joined by several third parties) challenged the WTO compatibility of India’s local content requirements for solar cells, and in 2010 Japan challenged the local content requirements of Canada’s feed-in tariff program. These disputes have provided little clarity about when such subsidies are permissible and when they are not, which has in turn prompted calls for legal reform to clarify this issue (Asmelash 2015).

Summary of WTO Article XX Disputes

| Case | Adopted | Issue/Challenge | XX(b) or (g)? | Chapeau? | Exemption Granted? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

US: Gasolinea |

5/20/96 |

US Clean Air Act rules for gasoline standards; favored domestic producers |

g |

No |

No |

|

US: Shrimpb |

11/6/98 |

US policy to protect sea turtles pursuant to Endangered Species Act; illegally restricted shrimp imports from some countries |

g |

No |

No |

|

EC: Asbestosc |

4/5/01 |

French restrictions on imports of asbestos-containing products; favored French substitutes |

b |

Yes |

Yes |

|

US: Shrimp (Art. 21.5)d |

11/21/01 |

Challenged US compliance with US-Shrimp I (1998) panel decision |

g |

Yes |

(Yes)e |

|

Brazil: Retreaded tiresf |

12/17/07 |

Brazil’s prohibition on imports of retreated tires |

b |

Yes |

No |

|

China: Raw materials |

2/22/12 |

China’s export restraints on certain raw materials (e.g., bauxite, silicon metal) |

No |

NA |

No |

|

EC: Seal productsg |

6/18/14 |

EU import restrictions on seal products, including from indigenous hunts |

NAh |

No |

No |

|

China: Rare earthsi |

8/29/14 |

Export restrictions on rare earths, tungsten, and molybdenum |

No |

NA |

No |

|

1/11/19 |

Challenged US “dolphin-safe” labeling rules |

g |

Yes |

Yes |

a United States—Standards for Reformulated and Conventional Gasoline.

b United States—Import Prohibition of Certain Shrimp and Shrimp Products.

c European Communities—Measures Affecting Asbestos and Asbestos-Containing Products.

d United States—Import Prohibition of Certain Shrimp and Shrimp Products. Recourse to article 21.5 by Malaysia.

e Noted in parentheses because, as explained above, this case was not new but merely involved a challenge to US compliance with a prior decision.

f Brazil—Measures Affecting Imports of Retreaded Tyres. Appellate Body Report.

g European Communities—Measures Prohibiting the Importation and Marketing of Seal Products.

h This issue was not considered by the appellate body because the measure failed to meet the requirements of the chapeau. However, it should be noted the panel found that the measure was not consistent with Article XX(b).

i China—Measures Related to the Exportation of Rare Earths, Tungsten and Molybdenum.

j United States–Measures Concerning the Importation, Marketing and Sale of Tuna and Tuna Products–Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by the United States.

In addition, more than 40 WTO disputes concern the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures. The most well known of them is the dispute regarding the moratorium on genetically modified organisms. This dispute revealed more than any previous disputes the ambiguous relation between WTO agreements and MEAs, in this case the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety. However, several other disputes related to sanitary and phytosanitary measures concern more directly public health than environmental protection. In parallel to the dispute-settlement process, but having received far less attention, is the WTO’s environmental negotiations track. Defined by the 2001 Doha Development Agenda, WTO delegates have been negotiating issues such as how to enhance the mutual supportiveness of WTO and MEAs, enhance the patentability of plants and animals, and increase market access for “environmental goods and services” by cutting or eliminating tariffs on such products. This has been a particularly active aspect of environment politics in the WTO, with negotiations surrounding the development of an environmental goods and services agreement ongoing since 2014.11 If concluded, the environmental goods and services agreement could greatly increase market access for products like wind turbines, solar panels, and water filtration systems.

Until quite recently, the WTO has really been the epicenter of trade-environment politics. Despite the growing number and strength of environmental provisions in PTAs globally, and in particular in US agreements, comparatively little media, activist, and/or scholarly attention has been directed to these agreements. This is surprising, because PTAs often include far more detailed and far-reaching environmental provisions than anything under the WTO. For example, the United States, Mexico, and Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA) contains the most detailed environmental provisions of any trade agreement to date (Laurens et al. 2019). It includes many provisions replicated from prior agreements, related to, for example, citizen enforcement, public participation, and MEAs. However, it also includes new provisions related to plastic pollution, wildlife trafficking, and food waste. As we explain in chapter 2, the re-negotiation of NAFTA has not changed much in terms of the environmental substance compared with the TPP. Negotiators remain, at least for now, in a holding pattern with respect to the future of trade-environment politics in PTAs.

What Do We Know about Trade-Environment Politics?

The WTO disputes detailed above have also catalyzed a wave of scholarly discussions surrounding trade-environment politics at the WTO. Much of this work has dissected the WTO’s approach to environmental dispute settlement under the GATT Article XX. In contrast to the environmental activist community’s strong critique of the WTO’s handling of environmental disputes, much of the scholarly literature is more measured in their assessment. Several scholars have argued that the WTO’s record is not as bad as its critics make it out to be, highlighting, for example, poor decision making by the United States and others in implementing environmental policies in ways that are unnecessarily discriminatory, even if the environmental policies in question were in line with Article XX exemptions (Charnovitz 2007; Desombre and Barkin 2002; Howse 2002; Jinnah 2003; Neumayer 2004). Others have been more critical, including Joel Trachtman (2018), who characterizes the WTO appellate body’s approach to environmental jurisprudence as incoherent and ineffective in addressing environmental exemptions. Still others have highlighted that the WTO’s approach to environmental and other social issues has led to an organizational “legitimacy crisis,” and a “chilling effect” on environmental policy development (Axelrod 2011a; Conca 2000; Eckersley 2004; Esty 2002; Stilwell and Tuerk 1999).

WTO-focused trade-environment scholarship has also delved into the empirical politics of trade-environment linkages, exploring, for example, how the WTO Secretariat has influenced trade-environment decision making at the WTO (Jinnah 2010; 2014), and the conditions under which the WTO has linked to environmental issues at all (Johnson 2015).12 Most recently, scholars have examined what Wu and Salzman have called the “next generation” of WTO environment conflicts, which have been largely related to renewable energy subsidies and industrial policy (2013). This work has explored, for example, the implications for low carbon development (Lewis 2015); why renewables have been challenged even though fossil-fuel subsidies have not (Asmelash 2015; Meyer 2017; de Bièvre, Espa, and Poletti 2017); and the domestic coalition politics that lead to protectionist policies for renewables (Hughes and Meckling 2017). These connections at the intersection between trade and climate change are sure to be an important locus of trade-environment politics for years to come (e.g., Kulovesi 2014). We discuss some of this work in more detail in the context of the broader linkage politics literature in chapter 3. There is indeed quite a bit of overlap between these two areas of scholarship, with trade-environment cases serving to demonstrate linkage politics dynamics for many scholars.

There is also a more limited body of work that looks at the WTO’s Committee on Trade and Environment, wherein delegates discuss environmental issues, including those outlined in the Doha Development Agenda, such as tariff reductions for environmental goods and services.13 Scholarship is divided on the effectiveness of the committee’s work, with some seeing important contributions to environmental cooperation and others responding more skeptically.14

Few scholars, however, have explored these questions as they relate to PTAs. The existing literature on PTAs has been largely focused on NAFTA and the novel set of environmental provisions it introduced in the mid-1990s, which went beyond the WTO’s environmental exceptions. Much of the NAFTA literature focused on the negotiation process (e.g., Hogenboom 1998; Markell and Knox 2003; Steinberg 1997); the environmental impacts of NAFTA writ large (e.g., Gallagher 2004; Hufbauer 2000); NAFTA’s novel Commission for Environmental Cooperation (Betsill 2007; Raustiala 2003); and how the NAFTA experience can inform environmental governance moving forward (Deere and Esty 2002).

The 687 other global PTAs currently in force have received surprisingly little attention. Aside from our own work leading up to this book, there has been very little analysis of the rapidly expanding politics of environmental governance through PTAs. Some of Jinnah’s prior work has examined, for example, differences between US and EU approaches to environmental protection through trade agreements (Jinnah and Morgera 2013); US approaches to strategically linking trade agreements to MEAs (Jinnah 2011); and the ways in which trade agreements serve as mechanisms for norm diffusion in Latin America (a topic developed in more detail in chapter 5 of this book; Jinnah and Lindsay 2016). Jean-Frédéric Morin’s prior work has analyzed the drivers for the inclusion of environmental provisions in PTAs (Morin, Dür, and Lechner 2018); the introduction of new environmental provisions in the trade governance system (Morin, Pauwelyn, and Hollway 2017); and the transatlantic convergence between the US and the European approach (Morin and Rochette 2017). Most recently, together we have analyzed how linkages to climate change could be better leveraged to offer similar benefits (Morin and Jinnah 2018).

Paul Steinberg, Dale Colyer, Ida Bastiaens, and Evgeny Postnikov are some notable exceptions. Steinberg provided an early assessment of how major regional trade organizations have handled environmental issues (2002). Building on this and a 2007 analysis from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Colyer provides a largely descriptive first account of PTA environmental provisions in global trade agreements (2011). Bastiaens and Postnikov (2017) provide one of the few interventions that analytically unpacks PTA environmental politics. Bastiaens and Postnikov (2017) nicely draw together Jinnah and Lindsay’s (2016) process-tracing analysis of environmental norms and policy diffusion through PTAs and Baccini and Urpelainen’s (2014) statistical analysis of the timing of domestic implementation of North-South PTA standards. Specifically, they argue that the nature of enforcement mechanisms directly affects the timing of trading partner implementation of environmental provisions in North-South PTAs. They show that while both US and EU enforcement approaches can be effective in facilitating environmental policy change in trading partner nations, the United States’ sanction-based enforcement mechanisms have catalyzed implementation of environmental provisions earlier than the European Union’s softer, more cooperative approach.

Despite these important interventions, the pace of trade-environment politics scholarship lags far behind the empirical developments in this area. In short, PTAs now engage deeply and directly in environmental governance, yet we know very little about how and why they do so and with what effects. In asking how environmental provisions in US PTAs impact environmental policy abroad, this book uncovers how the United States pursues environmental objectives through trade agreements, the factors that enable and constrain its decisions about which environmental provisions are included in PTAs, the impacts of these provisions on trading partner nations’ environmental policy and law, the extent to which these provisions enhance the effectiveness of environmental governance, and their diffusion in PTAs concluded by other countries.

Methods and Approach

This book is a broad intervention into the largely unchartered territory of environmental governance through PTAs. As such, we have identified a series of theoretically derived questions that aim to contribute to several core strands of the global governance literature. That is, rather than diving deeply into a narrow case of a single PTA, we look broadly at all US PTAs and seek to understand the diverse ways these agreements are shaping global environmental governance. Centrally, the book looks at how PTAs impact the global diffusion of environmental norms and policies through changes in domestic environmental law and international trade law, as well as through compliance with international environmental treaties.

We examine the United States for many of the reasons detailed above. The United States is a front-runner in terms of the innovation and reach of environmental provisions in its PTAs. Further, the extensive US PTA network (figure 1.5), coupled with the US practice of largely replicating (and extending) its environmental provisions from one PTA to the next, means that the capacity of US PTAs to influence environmental politics globally is substantial. Finally, as the largest economy in the world, the United States is a powerful actor in global trade politics. This imbalance of power between the United States and the majority of its trading partners (who are primarily developing countries), suggests that the United States likely dictates which environmental provisions make it into PTAs and which do not.15 This latter point is particularly important, because it provides us more confidence in tracing the direction of causality when, for example, examining norms and policy diffusion. Therefore, if PTAs do have any impacts on global environmental politics, the United States is a good case through which to observe them. In other words, we intentionally select on the dependent variable because we are not interested in, for example, the conditions under which PTAs influence environmental politics, but rather in if they influence environmental politics at all, and if so, what this looks like empirically. We peer into a black box.

Our core approach is based on a qualitative case study analysis that is deeply enriched by quantitative data derived from a large-scale dataset of global PTAs. We triangulate all findings to the greatest extent possible using a mixed-method approach that includes document analysis, interviews with key informants, and quantitative data from the most comprehensive coding analysis of environmental provisions in global PTAs to date. Specifically, we use the Trade and Environment Database (TREND; Morin, Dür, and Lechner 2018). This dataset covers a large number of PTAs, using the full texts of 688 PTAs signed between 1947 and 2016.16 TREND also stands out because of its fine-grained, content-based coding of 286 different types of environmental provisions, some of which are very common, while others are found in only one or two agreements. As these provisions were coded using software designed for qualitative analysis, TREND enables researchers to easily retrieve the full text of any environmental provision from any trade agreement. The dataset can also be used for quantitative analysis to compare groups of PTAs and critically map the impact of US provisions globally.

This comprehensive coding analysis is then used to enrich qualitative case studies that dive into the gritty politics of environmental provisions in US PTAs. We examine related but distinct theoretically derived questions in each of the analytical chapters (chapters 4–6). These questions and the data-collection methods used to explore them are unpacked in great detail in each of the individual chapters. Core to our qualitative cases studies in all chapters are detailed process-tracing analyses. We rely heavily on government documents and reports of international and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to trace, for example, how norms and policies have diffused across countries through PTAs. We complement this document analysis with interview data. We conducted 14 interviews with government officials who negotiated the PTAs under examination and/or oversaw their implementation, as well as with NGO representatives who were active in lobbying the US government on environmental aspects of its PTAs. Finally, when possible, we also interviewed trading-partner nations about their perspectives on how and why environmental provisions are included in US PTAs and the impacts of those provisions in their home countries.

Figure 1.6

Growth of US-PTA network over time (1970–2015)

This rich combination of quantitative coding through TREND, with qualitative process tracing through documents and interviews, allows us to paint the most detailed picture of US trade-environment politics available in the literature to date, and centrally, to compare the US practice to that of other countries.

Roadmap of the Book

Chapter 2 details the political and legal history of environmental provisions in US PTAs. Using the TREND database, it identifies all environmental provisions in US agreements beginning in 1985 with the US-Israel agreement, up to the signature of USMCA. Drawing on interview data and document analysis, this chapter explains the evolution of these provisions against the backdrop of concurrent US politics and legal developments. In so doing, chapter 2 lays the empirical foundation for the analytical chapters that follow. Chapter 3 explores the empirical and theoretical explanations for linking trade and environmental issues in PTAs. It first reviews the linkage politics literature to help us understand the structural functions that regime linkages provide. It then dives into the literature on why states choose to link issues, with a focus on explanations from trade-environment politics specifically. Finally, chapter 3 draws on interview data with key informants on US trade policy development to empirically reflect on the factors that enable and constrain the process by which the United States selects specific environmental provisions to include in its PTAs. On this point, we highlight that these provisions are largely defined by established US laws, such as the 2002 Trade Act and Trade Promotion Authority (“fast-track” authority).

Chapters 4 through 6 explore in depth the various ways that PTAs can impact environmental governance. Chapter 4 asks if linkages between PTAs and environmental treaties can impact MEA effectiveness. As will be explained in chapter 2, many US PTAs require, for example, that efforts to implement obligations under specific environmental treaties shall not be seen as in violation of trade law. Some recent cases go even deeper, requiring overhaul of domestic institutions in order to implement specific provisions of specific environmental treaties. Chapter 4 analyzes the extent to which these linkages actually impact the effectiveness of these environmental treaties. Looking through the lens of the US-Peru PTA and its linkages to CITES, the chapter argues that these MEA linkages can in fact enhance MEA effectiveness in important ways.

Chapter 5 turns to the impacts of PTA environmental provisions on domestic environmental policy in trading-partner nations. Specifically, through a detailed process tracing exercise, it examines the ways PTAs serve to diffuse environmental norms and policies from US domestic law into the domestic law of trading-partner nations. It does so by looking at how two characteristically US environmental norms (effective enforcement and public participation) diffuse through three US PTAs—NAFTA; the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR),17 and the US-Peru PTA—into the domestic law of several Central and South American trading partners.

Chapter 6 goes one step further in the study of diffusion by tracking the replication of environmental provisions within the global trade governance system. It asks whether environmental provisions that had first appeared in US PTAs were subsequently incorporated in other countries’ PTAs. Chapter 6 also asks whether provisions that were initially introduced in other countries’ PTAs were replicated by the US government in its own PTAs. This chapter argues that this cross-fertilization between US and foreign PTAs is one of the driving forces behind the evolution of the global trade governance system.

Finally, chapter 7 summarizes our findings, reflects on the potential negative impacts of PTA environment linkages, and provides recommendations for how trade-environment linkages should be considered going forward.

Summary of Research Questions and Findings

| Chapter | Core Question | Central Finding |

|---|---|---|

|

2 |

How has the US approach to trade-environment linkages evolved over time? |

Environmental provisions in US PTAs have gotten progressively stronger and more far-reaching over time. |

|

3 |

What factors enable and constrain the US government’s decisions to select environmental provisions for incorporation into PTAs? |

Rationales are diverse and overlapping. They include concerns about compliance costs, protectionist interests, domestic pressures from NGOs and others, contextual/situational factors, and trading-partner interests. Centrally, however, US decisions are circumscribed by domestic law and policy, which prescribe the specific provisions that may be included. |

|

4 |

How do environmental provisions in US PTAs impact the effectiveness of MEAs? |

Recent environmental provisions have enhanced the procedural effectiveness of certain MEAs by catalyzing implementation. |

|

5 |

Do PTAs serve as mechanisms of environmental norm and policy diffusion from the United States to trading-partner nations? |

Yes. Trading-partner nations replicate US domestic environmental provisions into their own domestic law via similar and/or verbatim PTA provisions. |

|

6 |

Are US PTA’s environmental provisions becoming a global standard? |

Yes. Some US PTAs’ environmental provisions were replicated by other countries, but significant differences remain between US agreements and agreements that do not involve the United States. |