5 Can Preferential Trade Agreements Diffuse Environmental Norms?

This chapter explores how preferential trade agreements (PTAs) can play a role in helping environmental norms and policies spread, or diffuse, from one country to another. We argue, through an empirical examination of three US PTAs, that PTAs have indeed served to diffuse environmental norms to trading-partner nations. We focus on two key norms in US environmental policy: effective enforcement (i.e., “bona fide decisions” to allocate resources to enforce compliance with environmental laws)1 and public participation (i.e., the inclusion of opportunities for citizen engagement in governmental decision making). We examine these norms across three US PTAs: 1992’s NAFTA, the 2004 Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR),2 and the 2006 Peru Trade Promotion Agreement. Our central argument is that key norms from US domestic environmental law and policy (i.e., public participation and effective enforcement) have diffused through environmental linkages within US PTAs and have been incorporated into domestic policy and practice in trading-partner nations. In illuminating this new mechanism of environmental norm diffusion (i.e., PTAs), we further demonstrate the potential for PTAs to shape environmental policy and practice across borders.

This analysis is particularly timely, given the geographic reach of the PTAs globally that are currently under (re)negotiation, and thus the potential for far-reaching environmental norm diffusion through these agreements. Recent scholarship has demonstrated how countries are increasingly diffusing their various trade provisions by templating language from one trade agreement to the next (Allee and Lugg 2016). For example, although the United States officially withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, the United States had influenced the TPP’s language more than any other country, with approximately 45 percent of the text of US PTAs from 1995–2015 found verbatim in the TPP, and 73 percent of the US-Jordan PTA copied directly into the TPP’s chapter on environment (Allee and Lugg 2016). Although remaining TPP countries have already removed some US-generated text on, for example, intellectual property from this PTA, the US thumbprint remains visible on the revised agreement as well.

This chapter examines how trade agreements between two or more countries can serve as mechanisms of environmental norm diffusion between the parties to these agreements. In other words, we examine how environmental norms can diffuse from one domestic system to another by way of trade agreements. We build on recent scholarship that suggests a strong potential for US trade agreements to influence environmental policies abroad through the increasingly far-reaching and prescriptive provisions contained in those agreements (Jinnah 2011).3 Our argument further extends findings that NAFTA’s implementation has resulted in environmental policy changes in Mexico (Baver 2011). We take the next step in this analysis by linking environmental policy change to several PTAs across several trading-partner nations. Further, we trace these changes in trading partners’ domestic environmental law and policy back to their source in US domestic law. In doing so, we show how these changes reflect new environmental norms that are not “home grown” but rather are imported from abroad through PTAs.

The next section situates our analysis in the broader literature on norm diffusion. We then outline our methodological approach, explaining how we know norm diffusion when we see it. This is followed by the empirical analysis, which traces our two norms of interest from US domestic environmental policy, through US PTAs, and into environmental policies and practices in trading-partner nations. The chapter’s conclusion discusses the implications of environmental norm diffusion for environmental performance and equity.

Norm and Policy Diffusion through Issue Linkage

Norms and policies are closely tethered. Norms set boundaries for political life by setting standards of behavior and defining expectations for what is or should be. In short, norms are collective ideas, principles, and/or expectations of behavior. International norms such as state sovereignty, abolition of slavery, human rights, and nonproliferation are strongly legalized4 in international law. Environmental norms tend to be weaker, characterized largely by lower levels of precision, for example. Environmental norms include such ideas as the “polluter pays” principle and common but differentiated responsibilities, which, when included in international treaties, are often left for states to interpret and operationalize in particular contexts. Here we examine key US norms that define ideas and expectations for how policy should be made (i.e., public participation) and enforced (i.e., effectively). We further demonstrate how these norms were either weak or absent in selected countries prior to their requirement through US PTAs.

Whereas norms identify goals, policies delineate how those goals should be achieved. Policies “internalize” or formalize norms in ways that can define specific pathways for action, more easily assign accountability, and sometimes enable enforcement through law (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998). Policies reiterate and articulate norms, but also explain how norms should be achieved through, for example, targets and timetables, reporting requirements, and institutional arrangements.

Norms are thus deeply embedded within policies (and laws). In international treaties, norms are often articulated in preambular text. For example, the Convention on Biological Diversity’s preamble establishes the need to “conserve biodiversity . . . for present and future generations,” and the WTO’s General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade preamble asserts that relations between countries “should be conducted with a view to . . . developing the full use of resources of the world.” Norms are also found in operational treaty texts, which are often translated into domestic law and policy through ratification and implementation. The extent to which policies reiterate norms, therefore, is a proxy, albeit an imperfect one, for whether or not norms have been internalized within a particular political system.

In highlighting how the United States incorporates environmental norms into its PTAs, this chapter engages discussions on norm diffusion and policy transfer. These literatures diverge with respect to terminology, methodology, and case selection. However, they are essentially interested in the same processes—the movement of ideas across borders—and there is substantial conceptual overlap in how they treat the transnational movement of norms and policies (Marsh and Sharman 2009). We, therefore, treat their contributions holistically, drawing on the strands of each that are most relevant to the analysis undertaken here.

Norm diffusion is the movement and adoption of norms across political borders. In brief, the literature points to four main theories of norm diffusion: learning, competition, coercion, and social construction (Dobbin, Simmons, and Garrett 2007; Morin and Gold 2014). In the environmental policy context, learning is often identified as an important driver of norm and policy diffusion; for example, “front-runner” states model environmental policies that are emulated and adapted by others (Busch, Jörgens, and Tews 2005). Competition, too, has been identified as a driver of diffusion, as states harmonize environmental policies upward (Vogel 1995). Coercion is relatively understudied in the environmental context. Finally, constructivists have underscored the role of international organizations in spreading ideas among states (Finnemore 1993).

Scholars have also identified specific mechanisms of norm diffusion, such as persuasion, localization, and institutional translation (Keck and Sikkink 1998; Acharya 2004; Bettiza and Dionigi 2014). We are in close conversation with this previous work on mechanisms in identifying a new mechanism of environmental norm diffusion: issue linkage and, more specifically, environmental linkages in PTAs. That is, by incorporating environmental provisions into trade agreements, the United States has not only used issue linkage to change bargaining dynamics, as discussed by previous scholars, but it has also diffused key US environmental norms into trading-partner countries’ domestic laws and policies.

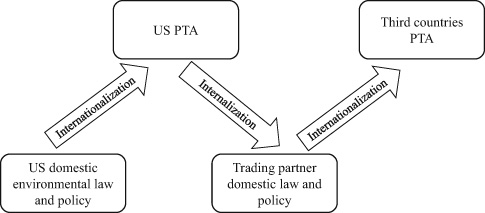

Whereas “tactical linkages” are typically deployed to gain bargaining leverage by making one’s behavior on an issue conditional on another’s behavior on a separate issue (Haas 1980; Axelrod and Keohane 1985), the linkages examined here link separate issues within a single agreement. That is, trade agreements require specific environmental policy changes in trading-partner nations that are tangential to the core objectives of the trade agreement. In some cases, such linkages even aim to achieve the environmental objectives required by an entirely separate environmental treaty, as discussed in chapter 4 with the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the US-Peru PTA. Whereas “tactical linkages” are used to shift bargaining leverage across agreements, the trade-environment linkages examined here achieve the adoption of tangential policy objectives by incorporating them directly into PTAs. Further, whereas previous work has shown how environmental norms diffuse from domestic law to international trade law (Allee and Lugg 2016), we go a step further in tracing the subsequent incorporation of those environmental norms into domestic law and policy in trading-partner nations.

Diffusion of environmental norms through trade agreements

In short, this chapter draws together the literatures on issue linkage and norm diffusion by demonstrating how environmental linkages in US PTAs serve as mechanisms to diffuse US environmental norms to trading-partner nations.

How Do We Know Norm Diffusion When We See It?

We use process tracing to demonstrate how environmental linkages within US PTAs serve as mechanisms to diffuse US environmental norms abroad. Specifically, we use documents, such as legal texts, US and Peruvian government reports, and NGO reports, to trace the movement of two US environmental norms—legalistic enforcement and public participation—from domestic US policy, through US PTAs, and ultimately into the domestic laws and policies in trading-partner nations.

We focus on these two specific norms because we find them consistently across most US PTAs, as well as in much US domestic law—both within and beyond the environment context. Public participation provisions include any language that requires the involvement of private actors and/or civil society in issues related to environmental governance. This might include provisions requiring the empowering of civil society, allowing for public comment, and/or requiring public notification of environmental decision making. Effective enforcement involves “bona fide decisions” to allocate resources to enforce compliance with environmental laws and, as discussed in chapter 4, can take a legalistic and/or managerial approach. Whereas managerial enforcement relies on cooperative mechanisms, such as capacity building, to incentivize compliance, legalistic mechanisms are designed to achieve compliance through coercive mechanisms, such as sanctions or penalties, which increase costs of non-compliance. The United States uses both types of mechanisms in its domestic and international environmental policies, and considers both to be central to effective enforcement. Further, at time of writing, the United States is the only country that utilizes strong legalistic mechanisms to enforce environmental provisions in its PTAs.

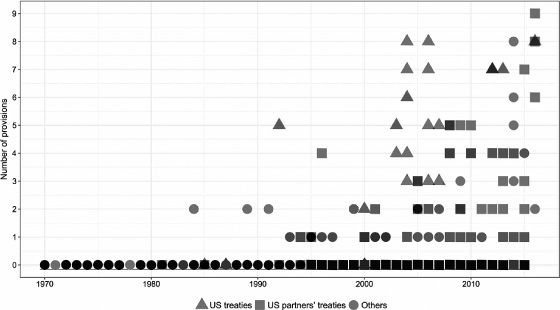

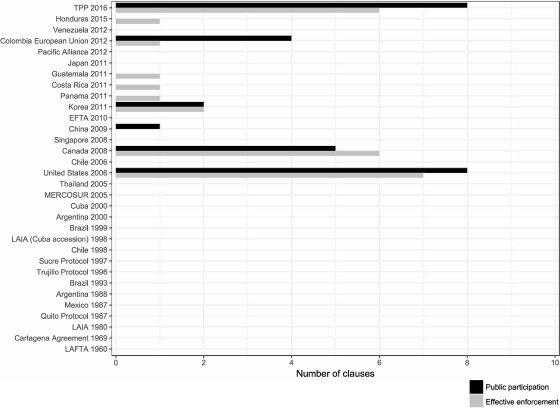

Figures 5.2 and 5.3 show the number of public participation and effective enforcement clauses in US PTAs, in comparison to those of its trading partners (in PTAs concluded after their agreement with the United States), as well as in the PTAs of other countries.5 In both figures, NAFTA (the triangle on the 1992 value of the x-axis) appears as a highly innovative agreement, with a record number of clauses on public participation and on effective enforcement. US PTAs (represented by triangles) are among those with the most clauses on these two issues over the entire period. Most non-US agreements that also include a high number of clauses on public participation and effective enforcement are PTAs signed by US trading partners with third countries. This further suggests that the United States is a driving force at the center of the global diffusion of norms related to public participation in environmental governance and effective enforcement of domestic environmental law.

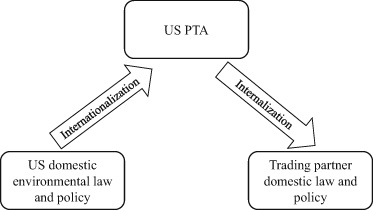

We want to show how (i.e., the mechanisms through which) these norms move across borders. To do so, we conducted our analysis in four steps. First, we showed the emergence of public participation and effective enforcement norms in US domestic environmental law and policy by examining key pieces of US environmental law and policy and explaining how these norms are central to those documents. Second, we showed how the United States has “internationalized” these norms (see DeSombre 2000) by replicating them in the three US PTAs examined in this study: NAFTA, CAFTA-DR, and the US-Peru PTA. We examined those PTAs for articulations of these norms to show how those PTA articulations are uniquely similar in approach to, and in some cases replicated verbatim from, those found in US domestic environmental law and policy.

Figure 5.2

Number of clauses on public participation in PTAs (1970–2016)

Number of provisions on enforcement of domestic measures in PTAs (1970–2016)

Third, and centrally, we looked for evidence of norm internalization into the domestic laws and policies of trading-partner nations. We argue that when norms have been internalized, they have begun to diffuse. Although we understand diffusion not as a binary concept but as existing along a continuum, we do not attempt to evaluate the degree of diffusion here. Rather, we analyzed whether effective enforcement and public participation have, at a minimum, begun to diffuse through issue linkage. Therefore, following Katzenstein (1996), we identified internalization by looking for the incorporation of these norms into domestic policy and practice. Like diffusion, internalization should be measured along a continuum, with deep behavioral change being an indicator of strong norm internalization, and policy change being a weaker indicator. The degree of internalization thus depends on the degree to which changes are internalized and also provides a preliminary indication of whether or not norms have diffused across borders.

Specifically, we looked at the policies that trading partners adopted to implement the effective enforcement and public participation provisions of their US PTAs. We analyzed documents from the US Trade Representative (USTR), the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and trading-partner governments that summarize the implementation activities in those nations. Using these secondary documents, as opposed to the laws and policies themselves, allowed us both to quickly narrow down the universe of relevant documents and to identify policies that were enacted specifically to implement the PTA.

Finally, we conducted a counterfactual analysis, reflecting on alternative explanations for the presence of public participation and effective enforcement in the domestic environmental policy and practices in trading-partner nations. We first looked for these norms in the PTAs that trading-partner nations had signed with other countries prior to their US PTAs. If these norms were important in domestic environmental policy prior to the US PTAs, we would expect to see them in those countries’ prior PTAs with other trading partners as well. The absence of such provisions from these PTAs would be a strong indication of diffusion from the United States. We ruled out preexisting internalization of effective enforcement and public participation norms through secondary analyses of domestic environmental policies in trading-partner nations prior to the entry into force of the US PTAs.

Effective Enforcement and Public Participation in US Law and Policy

Effective enforcement and public participation have long been central norms in US environmental law. Legalistic mechanisms feature prominently in the US domestic approach to effective enforcement through, for example, fines and criminal sentences. Public participation is also central to the US domestic environmental policy process through, for example, opportunities for public comment on draft laws and public opportunities for legal remediation. This section details the origins of these two norms in US environmental law and policy.

The US approach to effective enforcement of environmental laws has relied heavily on legal recourse for noncompliance through civil and criminal penalties. Central US environmental laws, such as the 1970 Clean Air Act and the 1972 Clean Water Act (CWA) emphasize formal rules and procedures and the extensive use of prosecution and litigation (Raustiala 1995). Under the CWA, for example, any wastewater discharge from a point source without a permit is subject to a fine of US$25,000 per day (Hodas 1995). Conservation-oriented laws, such as the 1973 Endangered Species Act and the 1900 Lacey Act (amended 2008), similarly impose civil and criminal penalties for violations.

These laws are strongly enforced. In 2014 alone, the US EPA completed 15,600 inspections and evaluations, issuing approximately US$80 million in criminal fines and almost US$100 million for federal administrative and civil judicial penalties (US EPA 2014). This is quite different from the approach taken by many US trading partners, which tend to have weaker enforcement mechanisms (Harrison 1995; Husted and Logsdon 1997).

Public participation is also prolific in US environmental law and policy. Public (or citizen) participation refers to “purposeful activities in which citizens take part in relation to government” (Spyke 1999, 266). It often includes access to information, access to justice, and participation in environmental decision making.

Public participation is incorporated into several parts of the US policy process. Policy development provisions often call for transparency and access to information. The 1969 National Environmental Policy Act, for example, incorporated public participation by allowing for public comment on all federal environmental impact statements (Spyke 1999). Public comment periods, public hearings, and citizen review panels provide core avenues for citizen participation under the Environmental Policy Act and several other US environmental laws (Fiorino 1990).

Public participation provisions also dovetail with enforcement provisions. For example, the CWA extends the responsibility for enforcement to citizens, calling for their participation in “the enforcement of any regulation, standard, effluent limitation, plan, or program” (§101(e), 33 U.S.C. §1251(e), section 101(e)). Finally, citizen suit provisions, such as those in the CWA, Clean Air Act, and Endangered Species Act, provide a mechanism for citizen enforcement by challenging a government’s failure to enforce its environmental laws.

Environmental Norms in US Preferential Trade Agreements

This section details how US norms of public participation and effective enforcement are replicated in three US PTAs, one from each phase of US trade policy described in chapter 3: NAFTA (1992), the CAFTA-DR (2004), and the Peru PTA (2006). Although NAFTA has received substantial attention in the environment literature on PTAs to date, CAFTA-DR and the Peru PTA have been largely understudied, demanding increased analytical attention.

North American Free Trade Agreement

NAFTA asserts that trade and investment should not compromise the environment, prohibits waiving or derogating from environmental measures to attract investment, and lists several MEAs whose trade provisions are effectively immune from challenge should they conflict with NAFTA’s trade provisions. The majority of NAFTA’s environmental provisions, however, are formally incorporated in the parallel North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC). The NAAEC requires parties to strive for “high levels of environmental protection” and “to continue to improve [environmental] laws” (Art. 3). The NAAEC further established the Commission on Environmental Cooperation (CEC) to support implementation of its environmental provisions, including those related to effective enforcement and public participation.

NAFTA put significant pressure on Mexico to improve its environmental enforcement activities by using both legalistic and managerial enforcement methods that reflect those in US environmental policy. On the former, for example, it requires parties to “ensure that judicial, quasi-judicial or administrative enforcement proceedings are available” for environmental law enforcement, and to create processes for public participation in investigations of alleged violations (Arts. 5 and 6). Many of the managerial enforcement mechanisms to ensure effective enforcement of environmental law and policy can be found in the NAAEC. Now standard in US PTAs, these bilateral and regional activities are referred to as “cooperative activities” and include things such as joint trainings to increase government enforcement capacity and partnerships with nongovernment stakeholders to promote environmental protection and effective enforcement.

The NAAEC also promotes transparency and public participation as a main objective of the agreement (Art. 1(h)). It established a public submission process for enforcement matters, which allows citizens to request a review of a party’s alleged failure to enforce its environmental laws. The NAAEC outlines procedures for this review and for making such information publicly available. The NAAEC also provides for a relatively weak consultation/arbitral process through which parties can resolve disputes related to their failure to enforce environmental laws. NAFTA further provides opportunities for the public to attend CEC meetings and be appointed to advisory committees, and it makes many CEC reports publicly available. The NAAEC also requires that many other documents be made publicly available and provides opportunities for public participation in procedural matters and cooperation activities (Art. 4.1).

Central American Free Trade Agreement

CAFTA-DR was negotiated under the 2002 fast-track authority, which, as discussed in chapter 3, required that specific environmental objectives be included in all US trade agreements. As such, CAFTA-DR’s environmental provisions were directly incorporated into the PTA itself rather than included in a “side agreement,” as was the case with NAFTA. CAFTA included a full chapter on environmental issues, which includes provisions on the effective enforcement of environmental laws and public participation in enforcement. The environment chapter also requires environmental cooperation between parties. To implement those provisions, the parties negotiated a parallel environmental cooperation agreement (ECA).6 Similar to the NAAEC, the ECA is a separate executive agreement negotiated alongside the PTA, does not require US congressional approval, and focuses entirely on operationalizing the PTA’s environmental cooperation activities.

Whereas trade ministries take the lead on PTA implementation, the ECA allowed the environment ministries in Latin American countries and the Department of State in the United States to define priorities and goals for environmental cooperation. The parties identified several goals, including effective enforcement of environmental laws. Similar to the concerns raised by civil society actors during NAFTA’s negotiation, several concerns were raised regarding Central American countries’ track records of environmental law enforcement during the CAFTA-DR negotiations (USTR 2003). While all of the Central American countries had passed a general framework law on the environment, a lack of fiscal and human resources limited their ability to enforce those laws (USTR 2003). As such, the parties focused primarily on managerial approaches, such as strengthening enforcement capacity and fostering public participation in the ECA. However, they did identify legalistic approaches to complement these managerial ones, such as a priority to ensure that judicial, quasi-judicial, or administrative proceedings are available to sanction or remedy violations of environmental laws (US Department of State 2012).

The environment chapter also provides a weak consultation process to resolve environment-related disputes. The US emphasis on effective enforcement is also evident in the decision to restrict access to CAFTA-DR’s much stronger, sanction-based dispute-settlement system to claims made under the effective enforcement clause alone. Yet remedy is still quite limited for all other environmental disputes, which must be handled through the weak consultation process. Also like NAFTA, CAFTA-DR’s environment chapter sets up a process wherein members of the public can request review of a party’s alleged failure to enforce its environmental laws.

The CAFTA-DR environment chapter also places a heavy emphasis on public participation. As we discussed above, the public submissions process allows individuals to request reviews of alleged violations of environmental laws. Parties further agreed to ensure the availability of “judicial, quasi-judicial, or administrative proceedings . . . to sanction or remedy violations of its environmental laws” (Art. 17.3.1). CAFTA-DR also provides for public involvement in environmental decision making. For example, individuals may be involved in advisory committees or submit comments and recommendations on environmental cooperation activities. Cooperation activities, too, have focused on enhancing public participation—for example, by supporting public involvement in environmental decision making through small grants to civil society organizations (OAS 2014).

US-Peru Preferential Trade Agreement

As with CAFTA-DR, the 2006 US-Peru PTA contains an environment chapter that mandates effective enforcement of domestic environmental laws and includes several new environmental provisions, such as one covering biodiversity conservation.7 It also contains several environmental provisions typical of other US PTAs, including those related to the implementation of MEAs that may otherwise conflict with trade rules as well as environmental cooperation to enhance capacity to protect the environment. Following instructions contained in the 2007 Bipartisan Trade Deal, the US-Peru PTA also includes greatly strengthened legalistic enforcement provisions for environmental matters by allowing unrestricted recourse for noncompliance through the PTA’s sanction-based dispute-settlement clause. Finally, the environment chapter contains an annex on forest sector governance, which addresses the economic and environmental impacts of illegal logging and wildlife trade and details how Peru should revise domestic forest policy to improve forest governance.8 Like CAFTA-DR, the Peru PTA established an ECA to implement environmental cooperation provisions of the PTA’s environment chapter, including through a strengthening of Peruvian national enforcement capacity. As with CAFTA-DR’s ECA, a separate agreement allowed environmental cooperation to be led outside of trade ministries and did not require US congressional ratification.

The environment chapter of the Peru Agreement requires effective enforcement in several ways. Centrally, the PTA calls for legalistic effective enforcement through prosecutorial discretion. This is supported by provisions on procedural matters, which mandate that parties investigate alleged violations of environmental laws and make such violations punishable through sanctions, fines, imprisonment, and/or facility closures. The strongest legalistic enforcement provisions in the US-Peru PTA environment chapter are found in the article on environmental consultations. As we noted above, prior agreements such as NAFTA and CAFTA-DR had contained comparatively weak provisions for environmental consultations. The US-Peru Agreement greatly strengthened these provisions, allowing parties to seek unrestricted remedy under the agreement’s primary sanction-based dispute-settlement system for any dispute under the PTA’s environment chapter.

The Forest Annex also contains several strong managerial and legalistic provisions on effective enforcement. On the former, these include requirements to increase the number of enforcement personnel, develop anticorruption plans, and strengthen existing institutions for enforcing forest laws. On the latter, these include provisions providing for strong civil and criminal liability and penalties and allowing the United States to directly engage in enforcement activities in Peru. Specifically, upon US request, Peru must audit specific producers or exporters, verify that such actors are in compliance with Peru’s forest laws, and allow US officials to participate in site visits to conduct these verifications.

Public participation is also plentiful throughout the environment chapter, its Forest Annex, and the ECA. These provisions, for example, require transparency of decisions and that judicial and administrative proceedings be open to the public, ensure public access to legal remedy, and mandate that Peru promote public awareness of environmental laws. Like NAFTA and CAFTA-DR, the Peru Agreement contains a process for citizen submissions asserting that either party is failing to enforce its environmental laws. The Forest Annex also requires transparency in the forest concession process, the incorporation of local and indigenous views to strengthen enforcement mechanisms, and increasing public participation in forest resource planning. ECA provisions enhance the Peruvian capacity to promote public participation in environmental decision making and enforcement and require public input in defining ECA activities in both countries.

In summary, norms of effective enforcement and public participation are deeply embedded in NAFTA, CAFTA-DR, and the US-Peru PTA. The ways that these norms are articulated in these agreements are very similar to articulations in US domestic environmental law and, in many instances, are essentially replicated from one US PTA to the next. In line with existing theory, this suggests that these norms diffuse through a process of “internationalization” from US domestic policy to US PTAs (Allee and Lugg 2016; DeSombre 2000; Morin and Gold 2014). In the next section, we take a crucial next step in analyzing the extent to which these internationalized norms have subsequently been internalized domestically in trading-partner nations through incorporation into domestic law and policy.

US Norm Internalization in Trading-Partner Nations?

In this section, we use norm internalization (as measured through policy changes) in trading-partner nations as a proxy for the diffusion of effective enforcement and public participation norms. We do this, first, by analyzing key documents for evidence that trading-partner nations are incorporating these norms into domestic policies and practices. Second, we discuss and reject alternative explanations for the internalization (and thus diffusion) of these norms in trading-partner nations’ domestic law and policy.

North American Free Trade Agreement

The internalization of effective enforcement is evidenced in several laws and policies implemented in response to NAFTA obligations. The CEC annual reports, for example, list many domestic environmental policies that were developed or revised to comply with the NAAEC. They highlight key policy changes, including Mexico’s 1996 revisions to its General Law on Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection (LGEEPA) and Canada’s 1999 revision of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA), both of which strengthen effective enforcement and public participation. The LGEEPA revision recognizes the right to information and allows for third-party compliance monitoring, and the CEPA revision incorporates new provisions allowing citizens to request investigations into alleged violations of domestic environmental laws (CEC 2001; Environment Canada 1999; CEPA Part 2). Enhanced enforcement is also evidenced through the increased number of inspections and verification visits in Mexico. For example, between 1971 and 1992, an average of 1,000 inspections for pollution control took place in Mexico per year (CEC 2001). This number increased dramatically following the entry into force of NAFTA, with 13,965 such visits between September 1995 and December 1996 alone (CEC 1996)!

NAFTA’s environmental cooperation activities also evidence the internalization of effective enforcement norms from the United States to Mexico. For example, in 1995, the parties established the North American Wildlife Enforcement Group to improve their collective enforcement of wildlife laws, along with the North American Working Group on Environmental Enforcement and Compliance to help build Mexico’s enforcement capacity. Subsequently, Mexico increased its inspections and seizures for compliance with wildlife laws more than threefold between 1995 and 1998 (CEC 1998).

CEC environmental cooperation activities have also catalyzed increased public participation. For example, in 1996, NAFTA parties developed the first North American Pollutant Release Inventory, modeled on the 1986 US Toxic Release Inventory. Environmental cooperation has also provided at least US$7 million for community grants, which supported a wide range of projects to engage citizens in environmental protection (CEC 2015).

Finally, in response to specific NAAEC provisions, Mexico also created several new institutions for public engagement, such as regional advisory councils, a national council, and an Advisory Council for Protected Areas, and guaranteed access to environmental information in the 1996 LGEEPA reform (CEC 2003). Canada’s 1999 CEPA amendment also strengthened citizen participation and access to environmental information by providing opportunities for public input at all stages of the decision-making process (Environment Canada 1999).

Central American Free Trade Agreement

CAFTA-DR countries have implemented, adopted, or improved approximately 150 new environmental laws that enhance effective enforcement and public participation in CAFTA-DR countries, largely with US financial support (OAS 2014). For example, several parties have developed mechanisms for better enforcing wastewater permitting and have held trainings on how to conduct inspections, audits, and environmental impact assessments. They also have supported trainings for judges, prosecutors, customs agents, police, and foresters to improve enforcement actions. US-supported cooperation activities under CAFTA-DR have also helped strengthen parties’ institutional capacity at multiple levels of government, improving their ability to monitor and enforce environmental laws, such as through modernizing permit systems. For example, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Costa Rica developed a web-based management system for CITES permits, and the Dominican Republic modernized their Energy Information Administration system with a geographic-information-system-based analytical tool (OAS 2014).

The United States has also worked through CAFTA-DR’s cooperation activities to help Central American countries improve opportunities for public participation in environmental decision making. For example, with US support, CAFTA-DR parties have published public guides to environmental laws and developed outreach campaigns, workshops, and media events to spread awareness of environmental laws (OAS 2014). The United States has also financed a small grants program, which trained 4,500 people in public participation tools and methods through 130 workshops across the CAFTA-DR countries (OAS 2014). Finally, in response to CAFTA-DR, the Dominican Republic and other Central American countries set up advisory committees through which citizens can raise environmental issues, which additional Central American countries are currently working on as well (Art. 17.6.3).9

US-Peru Preferential Trade Agreement

Peru has also enacted several new domestic laws aimed at implementing public participation and effective enforcement norms as articulated in the PTA. On effective enforcement, for example, Peru has created a new Ministry of Environment with an investigatory arm to verify compliance with environmental laws, and also established an independent forestry oversight body that has already conducted thousands of forest concession audits and assessed monetary fines in cases of noncompliance. In 2008, Peru modified its penal code regarding environmental crimes to greatly strengthen criminal penalties for forest-related crimes (Peru 2013). Between 2009 and 2013, Peru more than doubled the financial resources dedicated to the National Forest Authority for institutional strengthening (Peru 2013). Furthermore, in 2013, following allegations from US environmental NGOs of Peruvian failure to adequately implement the Forest Annex, US and Peruvian officials developed an action plan to prioritize areas for further forest sector cooperation. The plan identifies five such areas, including several related to effective enforcement, such as the need to ensure timely criminal and administrative proceedings to sanction violations of Peruvian forest laws (USTR 2015b).

Unfortunately, despite these procedural improvements, illegal logging continues to be a major problem in Peru, and the country has been severely criticized for not effectively enforcing provisions in the Forest Annex in particular (Urrunaga, Johnson, and Orbegozo Sánchez 2018). These failures reflect very mixed success in terms of effective enforcement in the country. Procedural changes in Peruvian environmental law related to effective enforcement have been made, reflecting at least some normative diffusion on this issue. However, there remains much work to do to fully enforce the broad requirements of the Forest Annex, indicating that normative changes to domestic law and policy are insufficient to actually address the problem.

On public participation, parties are currently setting up a public submissions process, similar to those of NAFTA and CAFTA-DR, and Peru has made more enforcement-related information public, including forestry information and forest management plans (Peru 2013). Following major protests across the country in 2009 related to failures to adequately involve indigenous people into environmental decision making as required by the annex, Peru has revised its policies in this regard (Urrunaga, Johnson, and Orbegozo Sánchez 2018). For example, it has increased consultations with indigenous groups on new regulations that affect resources located on their traditional lands (US GAO 2014). Although far from perfect, these changes do reflect improvements in the status quo regarding Peru’s domestic public participation practices.

Finally, US-funded cooperative activities are also instrumental in internalizing these norms in this case. The United States has invested approximately US$90 million into supporting implementation of the agreement’s environmental provisions (US GAO 2014; USTR 2013; Urrunaga, Johnson, and Orbegozo Sánchez 2018). Peruvian officials have participated in US training sessions on forest investigation and environmental prosecution and, in cooperation with US officials, have developed an updated training module to enhance investigation techniques and rates of prosecution for forest crimes (USTR 2015c).

In summary, evidence of the internalization of effective enforcement and public participation norms is present across all three agreements. Despite these high levels of internalization, in the case of the US-Peru PTA, compliance with newly created laws and policies continues to be a significant problem, especially as it relates to illegal logging. Nevertheless, analyses of PTA implementation from the USTR, CEC, Organization of American States, and trading-partner governments support the claims that these norms have been adopted into domestic law and policy as a means of directly implementing the environmental provisions contained in NAFTA, CAFTA-DR, and the US-Peru PTA. Although additional analysis will be needed to determine the strength of internalization, the proliferation of these norms in domestic policies across agreements provides strong evidence that norm internalization is occurring.

Alternative Explanations

Norm uptake into domestic policies suggests that norms of public participation and effective enforcement (as reflected in US PTAs) are beginning to internalize in trading-partner nations. The implementation reviews cited above strongly suggest that these norms originated in domestic US politics and were subsequently implemented in trading-partner nations following PTA obligations. The US Trade Act of 2002 further reinforces this claim, with several references to public access and with effective enforcement of environmental laws identified as among the “principal negotiating objectives” on the environment (sec. 2102, para. b(11)(A)).

Nevertheless, we briefly rule out other possible explanations here. It is possible that these norms were already present in the PTAs the US trading partners had previously negotiated with other countries. First, therefore, we examined all PTAs negotiated prior to those with the United States for any discussions of effective enforcement and public participation in environmental law or policy making. If such articulations are absent, this provides even stronger evidence that such norms diffused from the US PTAs. Even if such articulations are absent, however, it remains possible that trading partners simply had not yet “internationalized” these norms. We, therefore, also examined trading partners’ pre-US-PTA environmental laws for these norms. If such norms are weak or absent from such policies, this also provides strong evidence for our assertion that these norms diffused through the US PTAs and were not home-grown in the trading-partner nations.

Pre-US Preferential Trade Agreements

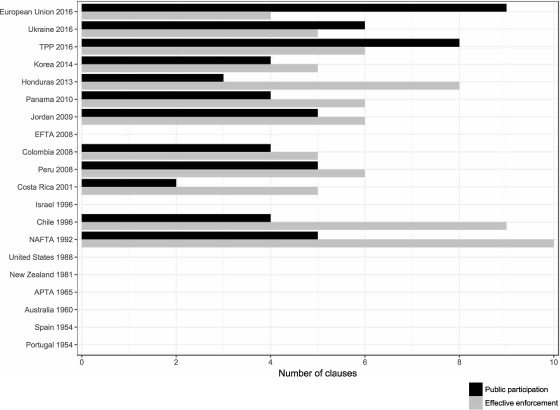

We found that few of the PTAs that US trading partners had entered into with other countries prior to their US PTA referenced the norms of effective enforcement or public participation. In fact, most US trading partners did not include environmental provisions in their PTAs prior to concluding an agreement with the United States at all. This appears clearly in figure 5.4 on Canadian trade agreements and figure 5.5 on Peruvian trade agreements. These figures show the number of environmental clauses on public participation and effective enforcement, as classified in the Trade Environment Database (TREND), for each trade agreement. They reveal that Canadian and Peruvian PTAs did not include such environmental clauses prior to the signature of their respective trade agreement with the United States.

Number of environmental clauses in Canadian trade agreements (in reverse chronological order)

Importantly, US partners often change their PTA model following their agreement with the United States and start including several environmental clauses in their subsequent PTAs. This appears clearly in figures 5.4 and 5.5, as the average number of clauses on public participation and effective enforcement increase significantly for Canada and Peru after their respective agreement with the United States. Thus, these provisions diffuse out of US agreements and reach countries that have not yet concluded an agreement with the United States. This process is illustrated in figure 5.6 below.

Figure 5.5

Number of environmental provisions in Peruvian trade agreements (in reverse chronological order)

Diffusion of environmental norms through trade agreements

As a result of this diffusion, some US trading partners had concluded PTAs with clauses on public participation and effective enforcement prior to negotiating an agreement with the United States. However, all of these countries had previously signed a PTA with an earlier US trading partner. For example, Canada included provisions on public participation in environmental law making and private access to remedies in case of violations to environmental law in its 1996 agreement with Chile. These provisions were reproduced from NAFTA and its environmental side agreement. Therefore, when Chile concluded a PTA with the United States in 2003, it had already agreed to US-style norms on public participation and effective enforcement. Likewise, Costa Rica had already accepted clauses on public participation and effective enforcement in PTAs with Mexico (1994) and Canada (2001) before it concluded a trade agreement with the United States in 2004, and these earlier PTAs included US-style provisions on public participation and effective enforcement. Rather than weakening the argument of this chapter by supporting an alternative explanation, these cases of indirect diffusion further illustrate the central role of the United States in the global diffusion of these norms.

Domestic Laws

The EPA undertook a detailed review of Mexico’s environmental laws prior to NAFTA. The review noted that Mexico “lacked adequate resources to construct a fully effective enforcement regime” (US EPA 1991, 5). It further noted that, prior to NAFTA, Mexico relied almost exclusively on administrative proceedings rather than the legalistic enforcement mechanisms favored by the United States (US EPA 1991). As we noted above, NAFTA required Mexico to implement more legalistic avenues for enforcement, mirroring this US enforcement approach. Prior to NAFTA, the Mexican and Canadian publics played a smaller role in environmental law enforcement (US EPA 1991; Paehlke 2000). Although Canada’s overall enforcement was strong, its environmental policy was “characterized by administrative discretion and relatively closed decision-making venues” (Paehlke 2000, 169).

Prior to CAFTA-DR, USTR reviewed the environmental laws and enforcement of the Central American parties. It noted the steps they had taken to develop environmental policies and institutions, but also their limited ability to enforce such laws—due, for example, to insufficient financial and human resources (USTR 2003). Furthermore, administrative regulations and procedures lacked transparency, which limited public participation (USTR 2003). The Organization of American States noted that with CAFTA-DR, both environmental law enforcement and public participation increased, improving their ability to respond to citizen complaints (OAS 2012).

The US environmental review that preceded the Peru agreement makes clear that Peru’s environmental laws had historically suffered from a lack of effective enforcement (USTR 2007b). For example, government agencies could impose only modest fines for noncompliance, and the judicial system allowed numerous opportunities for appeal (USTR 2007b). The review also noted that the PTA “has significant potential to improve environmental decision making and transparency in Peru” (USTR 2007b, 2). It explained that the PTA would improve public participation both through the public submissions process and by requiring Peru to ensure that its law and administrative proceedings would be made public and allow for public comment. This review further underscores the US role in strengthening public participation provisions through this PTA.

In summary, effective enforcement and public participation did not play an important role in the US trading-partner nations’ PTAs prior to those agreed with the United States, nor in their domestic environmental laws and policies prior to their US PTAs. These factors, combined with the often-templated language on effective enforcement and public participation from US domestic law into its PTAs, strongly suggest that these norms diffused through the US PTAs.

Conclusions

Prior chapters and studies have illuminated the long history in US trade policy of pursuing environmental objectives, the strengthening of such provisions over time, and, importantly, the potential for such provisions to shape environmental law in trading-partner nations. This chapter extends this work by tracing those international provisions through the process of their implementation in domestic law and policy in trading-partner nations and confirming the origin of those norms in US environmental policy. We found substantial evidence of key US norms making their way through US PTAs into the domestic law and policy of parties to NAFTA, CAFTA, and the US-Peru PTA. Interview data with US government representatives strongly support this finding, with key informants stressing the US role in pushing these norms even in the face of resistance (at least initially) from some trading-partner nations. In doing so, this chapter confirms prior hypotheses in the literature that environmental linkages within PTAs are important mechanisms of norm diffusion by mapping the pathway by which this diffusion occurs. In other words, this chapter demonstrates that environmental provisions do not merely sit unimplemented in international trade agreements, but actually have diffused into domestic law and policy through internalization of these provisions abroad. Importantly, as discussed in chapter 2 and supported by interview data, this implementation has been aided by US government grants tied to PTA implementation.

We first demonstrated that the norms of effective enforcement and public participation can be traced back to US domestic law. We highlight that beginning with NAFTA in the mid-1990s, the United States has systematically “internationalized” its core environmental norms of effective enforcement and public participation into its trade agreements by replicating norms from US domestic law and policy into these international agreements. Further suggesting this directionality of diffusion, effective enforcement is identified as a primary negotiating objective in the US 2002 Trade Act, and previously these norms were notably absent in the environmental laws of many US trading partners. Furthermore, Peru, NAFTA, and CAFTA-DR countries did not incorporate these norms into their PTAs with other countries prior to their agreements with the United States (SICE 2015), and effective enforcement and public participation provisions were weak in many of these countries (US EPA 1991; Paehlke 2000; USTR 2003; USTR 2007b). As we demonstrate here, following the passage of these three US PTAs, there is substantial evidence of US norms appearing in trading-partner nations’ domestic environmental law and policy. This suggests that environmental linkages within PTAs not only hold potential to serve as mechanisms of norm and policy diffusion, but are already serving this purpose across multiple agreements and countries.

One particularly important pathway for environmental norm diffusion through PTAs is the environmental cooperation activities undertaken to implement most US PTAs. As central features of US PTAs, environmental cooperation provisions provide a policy justification for allocating resources to trade-environment activities in trading-partner nations. Between 1995 and 2014, the United States funded more than US$196 million of trade-related environmental activities related to NAFTA, CAFTA-DR, and the US-Peru PTA (CEC 1994; US GAO 2014). Much of this work has been focused on improving effective enforcement and public participation in US trading partners through, for example, institutional capacity building. Indeed, these activities have already delivered improvements, as evidenced by CITES implementation improvements in the CAFTA-DR countries and Peru,10 increased public access to decision making in Mexico, and major changes to Peruvian civil and penal codes.

The diffusion of environmental norms through PTAs likely reflects several existing theories of norm diffusion, especially learning and the movement of ideas. However, these cases also raise questions about how powerful states may impose their broader interests on weaker trading partners, which would reflect diffusion through coercion, a relatively understudied concept, especially in the environmental context. However, in linking environmental provisions to the coveted preferential market access promised by US PTAs, the United States may actually be coercing environmental policy changes in trading-partner nations. Although the literature has historically linked preferences for environmental provisions in PTAs with higher levels of income, recent literature suggests that developing countries don’t necessarily favor environmental provisions in PTAs less than do developed countries (Bernauer and Nguyen 2015; Spilker, Bernauer, and Umaña 2018). However, developing countries likely prefer norms related to water, desertification, or indigenous communities over those emphasized by the United States. As such, the power imbalance, and potential coercion that may result, remains an important consideration in studying these negotiations.

Norm diffusion can also have important on-the-ground implications for civil society access to decision making in trading-partner nations. In discussing the public submissions mechanisms under NAFTA and CAFTA, one US government official interviewed for this study highlighted, for example, that it served as

an outlet for [civil society] to let their governments know about concerns. There are many examples where an NGO has been trying to get an issue heard, and now they can file through [the] citizen submission process. They came kicking and screaming into it, but now all of them recognize it as a positive force in their countries. I’m really happy about that and the success of that. It’s not the answer to everything but an important mechanism that didn’t otherwise exist. . . . It’s a way to get positive outcomes on environment that otherwise might not happen.

Finally, the nature of environmental provisions in US PTAs underscores the renewed importance of trade agreements for environmental problem solving and diplomacy writ large. The recently concluded negotiations among 11 countries on the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) is a fascinating indicator of the reach of US norms—including effective enforcement and public participation. US PTAs were the strongest influence on the CPTPP’s predecessor, the 2016 TPP (Allee and Lugg 2016). Aside from important provisions related to intellectual property and investor-state dispute settlement, most of the CPTPP’s provisions were adopted directly from the TPP. Therefore, although the Trump administration withdrew the United States from the TPP in 2017, US PTA provisions and norms have left their mark on the new agreement, including as related to effective enforcement and public participation. For example, the CPTPP’s environment chapter is subject to a sanction-based enforcement mechanism, similar to US PTAs. The CPTPP also contains text that is templated directly from US PTAs, such as the requirement related to “judicial, quasi-judicial, and administrative proceedings,” which appears in the CPTPP environment chapter verbatim from the US-Peru PTA. Particularly relevant to our discussion here, the CPTPP, like the US-Peru PTA, requires all trading partners to implement certain MEAs, such as CITES, making such provisions enforceable through the trade agreement’s sanction-based enforcement mechanism. Provisions related to the elimination of certain fishery subsidies, largely intractable in preexisting WTO negotiations for decades, were similarly included and made enforceable through these means. Most importantly, the parallel trends toward the increasing geographic scope of US PTAs, coupled with the progressively strong environmental provisions contained therein, signal an important turn in the future of environmental diplomacy and the diffusion of US environmental interests: for the first time, we are beginning to see international environmental provisions with actual enforcement teeth.