7 Conclusions

The Trump administration has pushed US trade policy into entirely new terrain, potentially tweeting us into a global trade war. He has slapped tariffs on aluminum and steel from some of his closest trading partners—the European Union, Mexico, and Canada; withdrawn the United States from the 2017 Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which the Obama administration negotiated with 11 other nations; and has aggressively re-negotiated NAFTA, which he famously called on Twitter “the worst trade deal ever signed” (Trump 2017). All of these actions have implications for the environment. Perhaps most relevant to trade-environment politics, in January 2018, Trump announced tariffs of up to 30 percent on solar imports, a move that some worry will actually shackle the $28 million US domestic industry, which relies on component imports from China for 80 percent of its supply chain (Eckhouse, Natter, and Martin 2018). It is possible that these solar tariffs, coupled with those on steel and aluminum, which are used in production of renewable technologies, will greatly chill global decarbonization efforts. These efforts rely on open trade so that the renewables industry can take advantage of economies of scale and global supply chains to keep production costs down (Chemnick 2018). At the same time, if the prices of steel and aluminum go up, global production will decline, which might exert downward pressure on CO2 emissions. Further, if Trump era policies catalyze an economic crisis, emissions may also decline in the short term. In short, the environmental implications of what is looking to be a new era in US trade policy could have mixed effects on the environment, with some being potentially devastating, particularly as it relates to climate change and decarbonization in the long term.

As this book has highlighted, however, the news is not all bleak. Rather, US trade agreements promise to continue making some important contributions to global environmental politics for years to come. Thanks to strong domestic laws, notably Trade Promotion Authority (TPA)—also called “fast-track authority”—Congress has baked in several important environmental provisions that the president must include in any newly (re)negotiated trade agreements. As detailed in chapters 2 and 3, this requirement is given in exchange for a simple up-or-down Congressional vote, without the possibility for amendment or filibuster. This promises, at least until 2021 when the current TPA expires, that any US trade agreements must, for example, require trading partners to implement their obligations under seven listed multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) and effectively enforce their existing domestic environmental laws. Importantly, violation of these environmental provisions is also subject to the full range of dispute-settlement provisions, including, for example, monetary penalties. As we discuss in chapter 5, the ability to effectively enforce these provisions through the trade dispute-settlement procedure is far stronger than any enforcement provisions under the listed MEAs themselves.

This book has further helped us to better understand how, why, and with what implications the US government pursues environmental objectives by linking them to its trade agreements. Before delving into future trends in the field, we summarize here our key findings and core arguments in each of these three areas.

1. How does the United States link trade and environmental issues in its trade agreements?

In chapter 2, we used the Trade and Environment Database (TREND), which codes 688 global trade agreements for environmental provisions, to trace the evolution of US trade-environment linkages from 1985 (US-Israel PTA) to 2017 (TPP). This analysis illuminated a strong trend toward more prescriptive and far-reaching environmental provisions over time.

We demonstrated how environmental provisions in US preferential trade agreements (PTAs) have evolved through five distinct phases. During phase 1 (1985–1999), the United States recognized connections between trade and environmental goals by incorporating highly circumscribed environmental exceptions to trade rules rather than pursuing specific environmental objectives directly. During phase 2 (1992–1999), US trade policy began to navigate potential synergies and conflicts between environmental protection and trade liberalization by creating environmental cooperation mechanisms and by leveling the playing field to ensure that Mexico and other developing countries did not benefit economically from lower environmental standards and lax enforcement. During phase 3 (2000–2001), the United States began to integrate accountability mechanisms for environmental issues. During phase 4 (2002–2005), the US Congress further strengthened those environmental provisions through Trade Promotion Authority requirements. Finally, during phase 5 (2006-present), the United States is aggressively using trade agreements to achieve environmental goals, especially those that the United States has already committed to under other domestic and/or international environmental instruments.

Existing US domestic trade law, such as the 2015 Trade Act, articulates specific environmental provisions that the United States must pursue in all of its trade agreements. However, these domestic laws merely set a minimum baseline for which issues must be included. Aside from a prohibition on addressing climate change issues through trade agreements, domestic trade law does not provide much guidance as to the limits of PTAs in addressing environmental issues, or on how environmental issues should be framed in PTAs. These decisions are instead developed through domestic political processes that involve, for example, interagency coordination, soliciting input from NGOs, and engaging trading-partner nations in dialogue about environmental issues.

2. Why does the United States link trade and environmental issues in its trade agreements?

Chapter 3 looked to the literature on linkage politics to better understand why the United States might choose to link environmental issues to its trade agreements by including environmental provisions. One overarching theme is that these linkages tend to be what Betsill and colleagues (2015) call “catalytic” linkages, which seek to facilitate action, as opposed to those that divide labor more efficiently. For example, the provisions related to MEAs in US PTAs, and associated cooperative activities under environmental cooperation agreements (ECAs) with Peru, Colombia, and Morocco, all sought to push these trading partners into higher levels of compliance with specific MEAs. Similarly, US PTAs have successfully pushed trading-partner nations to adopt stronger domestic laws for public participation in environmental decision making, as well as to effectively enforce their preexisting environmental laws. Importantly, enhanced cooperation through ECAs has channeled funds to implement MEAs at levels that far outstrip what is available under MEAs themselves. These funds have been used to help trading-partner nations to, for example, implement legislation and train scientific authorities.

Efficiency gains are, at best, an afterthought in these US trade-environment linkages. This is in stark contrast to what the environmental-regime overlap literature has illuminated. That literature has largely focused on “division of labor” linkages, highlighting, for example, how the biodiversity conventions have worked together on conservation of common species of concern, how the chemical conventions have held major conferences together, and how the Intergovernmental Forum on Forests’ agenda has been impacted by other regimes with interests in forest governance, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (Jinnah 2014; Selin 2010; Rosendal 2001b).

The US case has also illuminated that motivations for linking trade and environmental politics are multifaceted. Rationales are rooted in several existing, and sometimes competing, theories in the literature. In linking trade-environment issues in its PTAs, the US government sought to minimize compliance costs by choosing issues that it has already implemented domestically and were reflected in US domestic law. It was further responsive to domestic pressures, especially from the environmental NGO community, which were central in drafting key pieces of some of these agreements, and which advised Congress on how to construct the Bipartisan Trade Deal of 2007 (the “May 10 agreement”). The latter is particularly important in that it shaped the subsequent Trade Act of 2015, which gave the US president Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) and delineated the baseline environmental terms of all US trade agreements negotiated under TPA.

The United States is also guided, at least in part, by some protectionist interests. It has sought to protect domestic timber industries from illegal trafficking of species such as mahogany and cedar. Although these policies, namely the Lacey Act, have had some success in decreasing imports of these species into the United States, exports of likely illegal Peruvian timber to China, which lacks comparable legislation, are growing (EIA 2018). Interview data further suggest that US choices were also driven by temporally sensitive, contextual factors, such as data availability, NGO expertise, “hot topic” issues, and the politics of the current US administration. As one New Zealand government interviewee highlighted, the level of a country’s ambition also depends greatly on who the trading partner is and who they have negotiated with in the past. These data suggest, for example, that had the US-Peru PTA been negotiated now, the environmental provisions would likely look much different than what we ended up with in the agreement, focusing for example on today’s “hot topics” in the region, such as mining, rather than the PTA’s actual focus on forestry issues.

3. What are the implications of the United States linking environmental issues to its trade agreements?

Chapters 4–6 explored various implications of environmental linkages in US trade agreements. Chapter 4 asked: can trade agreements enhance the effectiveness of MEAs? Looking through the lens of the US-Peru PTA, we argue that they can and indeed have done so. Specifically, we demonstrate how trade agreements can enhance MEA effectiveness by serving as vectors to catalyze MEA implementation and by strengthening MEA compliance mechanisms. Drawing on the regime effectiveness literature, we argue that procedural effectiveness, as measured through improvements in MEA implementation and compliance, is already being enhanced in biodiversity MEAs. Not only do many US trade agreements already incorporate provisions that require implementation of MEAs, but in the last decade, they have begun to link compliance with those MEA-relevant provisions to the trade agreement’s full dispute-resolution mechanism. In complementing MEAs’ historically managerial mechanisms with PTA’s more legalistic ones, we argue that US PTAs can strengthen MEA compliance capacity.

We caution, however, that evidence is lacking regarding effectiveness improvements along other dimensions, such as problem solving and goal attainment. For example, in the US-Peru case, interview data and NGO reports suggest that illegal timber shipments have shifted to species not covered under the PTA and/or that trade flows may have merely shifted away from the United States and toward China (EIA 2018). This suggests that, in this case, effectiveness as measured through problem solving and/or goal attainment is not improved and may actually have negative implications. More research is needed to fully understand these implications.

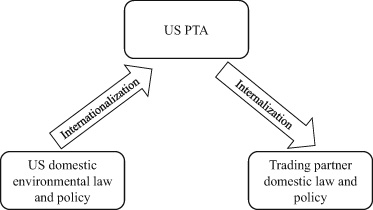

Chapter 5 asked: can free trade agreements diffuse environmental norms? Again, we argue here that they can and have done so. We examine this through the lens of two key norms in US environmental policy: effective enforcement and public participation. We examine these norms across three US PTAs: 1992’s NAFTA, the 2004 Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), and the 2006 Peru Trade Promotion Agreement. Through a detailed process-tracing analysis, we demonstrate how these two key norms have “internationalized” from US domestic environmental law and policy through environmental linkages within US PTAs, and subsequently how these norms have been “internalized” through their incorporation into domestic policy and practice in trading-partner nations (figure 7.1). We argue that in illuminating this new mechanism of environmental norm diffusion, we now better understand the potential for PTAs to shape environmental policy and practice across borders.

Importantly, we highlight how environmental cooperation activities, through environmental cooperation agreements (ECAs), are critical mechanisms for environmental norm diffusion. Largely ignored in the trade-environment literature, these findings suggest that additional attention should be paid to the potential and implications of environmental cooperation to diffuse environmental norms and policies to trading-partner nations.

Diffusion of environmental norms through trade agreements

Chapter 5 also cautioned, however, that powerful states may coerce weaker trading partners to adopt their environmental preferences in exchange for US market access. Indeed, interview data suggested that the US-designed Forest Annex to the US-Peru PTA was “shoved down [Peru’s] throat” in exchange for market access. This type of diffusion through coercion is a relatively understudied concept in the environmental context. This is not to say that developing countries favor inclusion of environmental provisions in PTAs less than developed countries do (Bernauer and Nguyen 2015). However, developing countries likely prefer provisions related to water, desertification, or indigenous communities over those emphasized by the United States. As such, the power imbalance, and potential coercion that may result, remains an important consideration in studying these negotiations.

Finally, chapter 6 asked: do US PTA provisions become global standards? Again, we argue that they do. More specifically, we find that several important environmental provisions, which first originated in US PTAs, have found their way into the PTAs of US trading partners and into those of third countries’ PTAs. This is notably the case of environmental exceptions to commitments on investment protection. They first appeared in NAFTA and other US agreements and were subsequently replicated in PTAs that do not involve the United States. We further demonstrate that the environmental provisions of other countries’ agreements inspired some recent features of US PTAs. For example, the European Union traditionally includes in its trade agreements detailed provisions on specific environmental issue areas tailored to the particular ecological context of their trade partners. Recent US agreements build on this European approach and add issue-specific provisions, especially on forestry, fisheries, and endangered species, in addition to provisions related to the environment in general. Centrally, chapter 6 argues that this cross-fertilization between the PTAs of different countries is a critical mechanism in the evolution of environmental provisions in the trade system.

Chapter 6 also identified two important limits to this cross-fertilization process. First, recent US agreements are not as innovative as NAFTA was for its time. They also borrow less from other countries. Most recent US agreements duplicated environmental provisions from earlier US agreements. This standardization will likely slow down the cross-fertilization between PTAs. Second, flows of influence are lopsided in favor of high-income countries. While some developing countries have successfully introduced some innovative environmental provisions in the trade system, notably in genetic resources and traditional knowledge, most provisions that were replicated by several countries originally come from high-income countries. This implies that some issues that are important for developing countries, such as desertification, access to fresh water, and adaptation to climate change, are rarely addressed in the context of trade negotiations.

Finally, it should be noted that non-environmental clauses can also have environmental consequences. This is partly related to negative externalities: trade liberalization creates economic effects (more production, agricultural specialization, long distance shipping, etc.), which have clear environmental consequences. Some may also argue there are also regulatory impacts, as some trade commitments limit the capacity of governments to regulate the environment, including via a “chilling effect” of sorts. On the other hand, PTAs’ trade commitments might actually do more for the environment than their environmental provisions by, for example, favoring the development and diffusion of environmental technologies. These are all questions that were outside the scope of our analysis here, but demand further investigation.

Unintended Consequences and the Importance of Public Participation

Environmental provisions hold much promise for strengthening environmental governance writ large. However, if trade is used to promote environmental goals at the expense of other social issues, problems of inequity and instability can result. Power differentials between countries is a key variable to consider in this regard. Although the inclusion of both baseline and more progressive environmental provisions in US PTAs promises important environmental benefits, there are also potential risks. This is especially the case when there are power imbalances between trading partners, like between Mexico and the United States. Is it a good thing for the United States to push its environmental preferences on trading partners in exchange for market access? Not always. When domestic institutions in trading-partner nations are not adequately robust, implementation of far-reaching environmental provisions can lead to corruption, practices that further entrench existing inequalities, and even loss of life.

The case of the US-Peru PTA is particularly instructive in this regard. The domestic political fallout in that country in the lead up to the entry into force of its PTA with the United States resulted in social unrest and violence that have been blamed, in part, on the PTA and, especially, on the Peruvian government’s use of the PTA as a political cover to push through its broader social agenda as it related to forest and land-use issues. The case therefore highlights one particularly important possible concern: trade partners’ potential use of PTA requirements as a shield for implementing broader social reforms without adequate consultation processes with impacted stakeholders. Because this case is so instructive in thinking about lessons going forward, it is worth recounting the story as a cautionary tale for the future of trade-environment linkages in trade agreements. This section recounts the story in some detail and suggests some possible policy options to avoid this tragic outcome in the future.

In April 2009, one month after the US-Peru PTA was signed, indigenous communities began to block roads near Bagua, Peru, in peaceful protest of the Peruvian government’s action to implement the US PTA. The protests continued until June 5, 2009, when the Peruvian government decided to clear the protesters from the “Devil’s Curve,” a stretch of the Belaunde Terry Highway near Bagua, approximately 600 miles north of Lima. What was a peaceful protest quickly turned violent. Official estimates report that 34 people, including 10 civilians and 24 police officers, were killed in the standoff. Hundreds more were injured. Unofficial reports suggest that several more protesters were “disappeared” (Rénique 2009), with up to 40 bodies thrown into the local river by police helicopters (Merino 2010, cited in Stetson 2012). Many suggest that what has come to be known as the “Bagua massacre” was a result of Peruvian President Alan García’s circumvention of domestic laws in order to implement provisions of the PTA (de Jong and Humphreys 2016; Hughes 2010; Rénique 2009; Stetson 2012; EIA 2018). Interview data (and common sense) suggest this was in part due to strong pressures from the US government to implement the annex very quickly after it was signed, with threats that in order for the PTA to enter into force, certain implementation thresholds must be met. Specifically, following the signing of the PTA in April 2006, the Peruvian Congress granted García the authority for a 180-day period to pass a series of legislative decrees, which have come to be colloquially known as la ley de la selva (the law of the jungle; Escobar Torio and Tam 2017). Specifically, Law 29157 granted García the power to “legislate on matters related with the implementation of the Agreement to promote commerce between Peru and the USA” (de Jong and Humphreys 2016, 558). García argued these decrees were necessary to bring Peruvian domestic laws into compliance with its obligations under the PTA (de Jong and Humphreys 2016; Hughes 2010; Stetson 2012).

Acting upon this authority and without any public consultation, García subsequently issued 108 legislative decrees, including a new forest law, which, among other things, opened up tropical forest land to mineral extraction and agro-industrial production and undermined collective property rights of Peru’s indigenous people (Rénique 2009). For example, two of the most controversial decrees, LR No. 1064 and 1090, would together make it possible to change the legal status of 60 percent (more than 45 million hectares) of Amazonian land from forests to agricultural lands (Carlsen 2009; de Jong and Humphreys 2016). Other decrees weakened voting rights for local communities regarding lease or sale of communal lands (LD 1015) and transferred zoning authority from local communities to the central government (LD 1064; Escobar Torio and Tam 2017). That the decrees were pushed through so quickly was very problematic. As one NGO representative said, “nobody had the time to read them, much less comment on them or engage.”

Following domestic and international pressure regarding the issue, including international media coverage of the Bagua massacre, García repealed two of the most controversial of the decrees (LD Nos. 1064 and 1090). The Peruvian Parliament appointed a committee to investigate the case, resulting in four official reports, which among other things accused the Peruvian Minister of Commerce Aráoz of exaggerating the possible impacts of repealing the decrees on the US-Peru PTA and declared the decrees unconstitutional because adequate consultation processes were not followed (Arse 2014; de Jong and Humphreys 2016). Although the Peruvian Congress enacted the Law of Consultation in May 2010 to require prior informed consent of indigenous communities, García refused to sign it, and it was not signed until August 2011, one month after his predecessor, President Ollanta Humala, took office (Arse 2014).

Although all of the decrees were intended to relate to the environment chapter (chapter 18) of the PTA, de Jong and Humphreys’ analysis of all 108 decrees suggest that only 25 of them actually relate to environmental issues (2016, 558). Others have further suggested that, at most, only 20 percent of the decrees relate to PTA implementation at all (de Jong and Humphreys 2016). The latter strongly suggests that the PTA was indeed used a shield by the Peruvian government to push an alternative social agenda that was at best marginally related to the PTA itself. One NGO key informant lamented that the US government did not take the NGO community’s concerns about what was unfolding in Peru during this time seriously enough. That informant further underscored that s/he “continue[s] to see that what happened in Peru after the Bagua incident was the result of a really unholy mix of fierce economic interests taking advantage of that very specific circumstance that the new trade deal provided them, as well as the added bonus of a naïve [US Trade Representative (USTR)] office who at that point was very trusting of its Peruvian counterparts and didn’t want to hear the warnings of the NGO community once the deal was signed.” To be fair, this same informant added that:

I don’t blame Bagua on the annex; that’s the wrong conclusion to derive from this story. But there is a lesson here about what the knock-on effects are when you shoehorn environmental reforms into trade agreements when institutions are not aligned on what it will take to implement them. There could have been a better process from both government and NGOs to make sure we put the right things in there.

Although the official Peruvian government position, as underscored by interviews with Peruvian government officials, is that the Bagua massacre was not related to the PTA at all, this position is widely criticized, including by NGO and US government interviewees. Rather, it is widely understood that the lack of adequate participatory processes in Peru’s sweeping passage of implementing legislation for the PTA was largely responsible for massive social unrest and even loss of life.

The promise of US market access, coupled with the power differential between the United States and Peru in this case, helps to explain why Peru accepted such deeply prescriptive environmental policies in this PTA, and why it was subsequently able to push through a host of policies without adequate domestic consultation under the auspices of the PTA implementation. This combination of conditions is not unusual in US trade negotiations, nor more broadly. In order to avoid this problem in future, the United States (and other powerful countries) might consider building stronger participation requirements into its PTAs. As discussed in chapter 5, public participation in environmental decision making is already a key norm the United States incorporates into all of its trade agreements. These provisions could be strengthened to require such things as prior and informed consent from local communities who will be impacted by PTA implementation. Allowing for longer implementation periods in trading-partner nations may also help to avoid this problem in future. Peru only had 18 months to implement the Forest Annex provisions. This not only put a lot of stress on Peru to push through legislation without allowing for adequate consultations, but also provided political cover for doing so domestically. Further, the United States could benefit from additional public consultations at home, in particular with US NGOs who specialize in environmental issues in trading-partner nations, such as the Environmental Investigation Agency’s expertise in forest issues in Peru. Although there are existing mechanisms to consult with such organizations, better consultation processes can both identify potential flares before they ignite and potentially avoid tragedies like we saw in Bagua in 2009. Slowing this implementation process down through consultation will also have the important benefit of ensuring that adequate domestic institutions are in place to implement PTA provisions. Despite this implementation problem, one NGO interviewee highlighted a thin silver lining to the Bagua massacre: it triggered the development of robust public participation laws in Peru.

The Future of US Trade Environment Politics

The future of US trade-environment politics is somewhat uncertain. As we noted in the opening section of this chapter, in withdrawing from the TPP, demanding a renegotiation of NAFTA, and slapping tariffs on major trading partners, President Trump has destabilized global trade governance, with uncertainty about how these decisions will impact many things, among them the environment. Yet, as we argue below, these actions are actually unlikely to weaken environmental protection. The TPP, and its environmental agenda, will continue without the United States under another name, and the renegotiated NAFTA has actually resulted in some stronger environmental provisions (Laurens et al. 2019). We flesh out these arguments below. We further point to some other emerging areas of trade-environment politics that are likely to be, or in our view should be, important in the years to come. These include the utilization of trade agreements to pursue climate change interests and an emerging cadre of disputes within the WTO surrounding renewable energy technologies. We conclude with a list of core policy recommendations that we suggest should guide governments in developing trade-environment linkages going forward.

Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership

Following the US withdrawal from the TPP in 2017, the remaining 11 countries maintained the agreement, with very few changes, and renamed it the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).1 The CPTPP was agreed on March 8, 2018 and entered into force on December 30, 2018. As a result, the US thumbprint remains clearly visible on the CPTPP’s environmental provisions. Notably, the CPTPP’s environment chapter contains an article on Conservation and Trade that explicitly addresses the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)—a hallmark of US trade policy since 2009. The CPTPP requires parties to “adopt, maintain, and implement” CITES among several other managerial-style enforcement requirements, such as sharing information, strengthening forest management capacity domestically, and better involving NGOs in implementation. Like other recent US PTAs, CPTPP also subjects the environment chapter to the same dispute-resolution procedures as the rest of the Agreement, including through sanctions. Notably, however, as it relates to CITES implementation, the CPTPP requires that a violation can only be established if a Party’s failure to “adopt, maintain, or implement” CITES is done in a manner that affects trade or investment between the parties (Art. 20.17, fn. 23). This sets a comparatively high bar for demonstrating CITES violation in comparison to the US-Peru TPA, which did not require a violation to impact trade or investment.

CPTPP contains several other environmental provisions that are clearly derived from US trade policy. For example, the agreement requires parties to: enforce their domestic environmental laws; enhance mechanisms for public participation; provide for judicial, quasi-judicial, or administrative proceedings for enforcement; establish public submissions processes; develop environmental cooperation frameworks; and critically, all such provisions are fully enforceable through dispute settlement—a hallmark of US trade policy that has not been adopted by CPTPP countries otherwise, apart from their earlier PTA with the United States.

As is standard practice in US trade policy, these environmental provisions reflect US efforts to “level the playing field,” and would not have been new obligations for the United States. In other words, that the United States will no longer be required to implement the CPTPP’s environmental provisions may not really matter that much, because it has already implemented most of them. The environmental provisions were largely designed for other countries to implement. There are some exceptions, of course. For example, interview data suggest that the biodiversity provisions were largely pushed by Peru. Similarly, the CPTPP requires parties to cooperate on transitions to a low emissions economy (without explicitly mentioning climate change), which was also pushed by other countries. However, such provisions are weak and unenforceable, and would have been unlikely to result in any important policy change in the United States regardless.

There is, however, one exception, which will likely result in negative environmental impacts following the US withdrawal. This is related to the removal of a provision in the 2016 TPP that mirrored the US Lacey Act, which required countries to respect domestic laws of foreign countries with respect to trade in endangered species. That is, the provision would have made it illegal for all parties to import a species from another country if that species was taken illegally from its country of origin and is particularly relevant to illegal timber trade. The United States fought hard, supported and pushed by key environmental NGOs, to include this Lacey Act language in the TPP. They were opposed strongly by Chile, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Vietnam on the grounds of practical difficulties, especially concerning knowledge of foreign countries’ domestic law. Unsurprisingly then, when the United States withdrew from TPP, the “Lacey language” was removed. Some commentators underscore the missed opportunity this watering down of anti-illegal logging language from CPTPP presents for the world’s forests and the people whose livelihoods depend on them (Barber and Li 2018).

As such, aside from the so-called Lacey Act provisions, which were removed after the United States withdrew, the environmental impacts of the CPTPP are unlikely to change much as a result of the US withdrawal. Rather, as the CPTPP parties begin to implement their environmental obligations, it will present another interesting empirical case of norm and policy diffusion to examine. Similarly, if we observe enhanced implementation of CITES and other listed MEAs in connection with CPTPP implementation, we may have additional evidence of the role PTAs can play in enhancing some dimensions of MEA effectiveness.

United States, Mexico, and Canada Trade Agreement

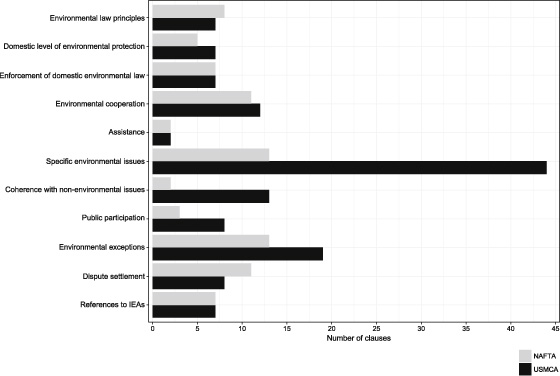

Another important contemporary development catalyzed by the Trump administration is its initiation of the renegotiation of the 1994 NAFTA on August 16, 2017. The renegotiation was based on a set of publicly available negotiating objectives, which were developed and revised by the USTR based on hundreds of hours of consultations with members of Congress, private sector representatives, labor representatives, NGOs, and others (USTR 2017b). Given Trump’s hostile track record on environmental issues, some might have expected his administration to water down NAFTA’s landmark environmental provisions. However, the United States, Mexico, and Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA) not only brings most environmental provisions into the core of the agreement, rather than in a side agreement as in NAFTA, but it also contains more environmental provisions than the original agreement, notably on domestic levels of environmental protection, environmental cooperation, coherence between environmental policies and non-environmental issues, public participation, and environmental exceptions to trade commitments (Laurens et al. 2019). Figure 7.2 shows that the most striking difference between USMCA and its predecessor is the number of specific environmental issues they each address.

In fact, the only categories where NAFTA includes more environmental provisions than USMCA are environmental principles. Unlike NAFTA, USMCA does not refer to the prevention principle—and dispute settlement. Indeed, the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC) included a specific dispute-settlement mechanism in case of failure to enforce domestic environmental laws (part V), whereas USMCA addresses disputes in which a party does not comply with the environmental provisions of the agreement.

What explains these strengthened environmental provisions in the USMCA? The answer is actually fairly straightforward. Because NAFTA was renegotiated under Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), the US administration had a strong incentive to include all environmental provisions required by TPA-2015. These include, for example, requiring trading partners to implement specific multilateral environmental agreements, among several other requirements, detailed in chapter 2. Although the 1994 NAFTA was progressive on environmental issues for its time, the environmental provisions required by TPA are much more far-reaching. Further, the USMCA article on wildlife trafficking (Art. 24.22(7)b) reflects the Trump administration’s demonstrated interest in ensuring effective enforcement, including with respect to wildlife trafficking, as evidenced through his 2017 Executive Order on Enforcing Federal Law with Respect to Transnational Criminal Organizations Preventing International Trafficking,2 as well as through his administration’s block of illegally harvested timber in Peru, even if the motivation may have been to protect the US domestic timber industry. The illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing and fisheries subsidies provisions (USMCA Art. 24.20) are also reflective of long-standing negotiations on these issues within the WTO (Campling and Havice 2017).

Number of environmental provisions in NAFTA and USMCA

Climate-Progressive Trade Agreements and Missed Opportunities

The failure to address climate change directly in the context of US PTAs is a significant limit to US efforts to reconcile trade liberalization and environmental protection. In principle, PTAs hold great potential to enhance climate change governance (Morin and Jinnah 2018). In contrast to multilateral negotiation on climate, PTAs involve fewer parties at the bargaining table, they are supported by strong enforcement mechanisms, and they allow for policy experimentation. Yet, by and large, trade negotiations have not seized this opportunity.

Some US agreements include modest provisions on renewable energy and energy efficiency. The European Union addresses climate change more directly in its PTAs. Some European PTAs include commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and references to multilateral climate agreements. In 2018, the European Union announced that it would refuse to sign trade agreements with countries that have not ratified the Paris Agreement on climate change (Stone 2018). A few months later, the PTA between the European Union and Japan became the first trade agreement to include an explicit reference to the Paris Agreement. Yet, even EU agreements do not include specific and enforceable provisions on issues at the very heart of trade—climate linkages, including carbon taxes, fossil-fuel subsidies, carbon credits, and emission trading (Morin and Jinnah 2018).

One of Canada’s objectives for the renegotiation of the NAFTA was to “fully support efforts to address climate changes” (Freeland 2017). However, USMCA does not break new ground on the climate front. US TPA specifically prohibits the president from including in its trade agreements commitments to any “greenhouse gas emissions measures, including obligations that require changes to United States laws or regulations or that would affect the implementation of such laws or regulations, other than those fulfilling the other negotiating objectives in this section” (Section 914 para. (b)). As explained in chapter 2, this drastically circumscribes the potential of US trade agreements to address climate change in a meaningful way.

Renewable Energy Disputes in the WTO

Another important emerging area of trade-environment politics surrounds a spate of disputes in the WTO challenging subsidies for renewable energy. Interestingly, although fossil-fuel subsidies outnumber those for renewables subsidies by a ratio of 4:1, to date, only renewables have been challenged under the WTO dispute-settlement mechanism (Asmelash 2015; Van de Graaf and van Asselt 2017). The first such renewable energy dispute was filed in 2010 by Japan, later joined by the European Union, challenging Canada’s use of the feed-in tariff in Ontario, which guaranteed minimum electricity prices for solar and wind sources if a baseline domestic content requirement was met (Van de Graaf and van Asselt 2017; WTO 2013). In that dispute, the WTO dispute-settlement body ruled against Canada, not because the subsidy was deemed non-compliant with the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures, but because the policy violated national treatment obligations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures. A similar outcome resulted from a case involving a US challenge to domestic content requirements in an Indian power purchase agreement with solar producers (WTO 2016).

There have since been at least eight more cases filed challenging domestic support of, for example, solar, wind, and biofuels industries in WTO member states. Most of those have not yet been resolved, leaving much uncertainty about the future compatibility of renewable energy subsidies in WTO member states. As more and more states are turning to renewables as a source of decarbonization, these disputes are likely to increase into the future. As Joanna Lewis cogently argues, this underscores the importance of navigating the fundamental tension between the political economy of domestic renewable energy support (i.e., creating jobs and ensuring domestic technological development) with the basic principles of the global trade regime (i.e., reducing barriers and non-discrimination), before any negative implications for global decarbonization are realized (Lewis 2014). PTAs can play a role in navigating these tensions if the United States and others major players can begin to delineate rules under which renewables support is permissible. Although there are challenges for the United States in particular for including such provisions due to TPA’s prohibition on including measures related to greenhouse gas emissions, renewables rules need not necessarily conflict with TPA if such rules are geared toward securing other environmental benefits. For example, renewables policies could be developed under the auspices of decreasing emissions of criteria pollutants (that largely correlate with greenhouse gas emissions) for the purpose of protection of public health.3

Environmental Goods and Services

Finally, another important ongoing issue in trade-environment politics is the negotiations surrounding a possible new plurilateral agreement on environmental goods within the WTO. These negotiations began in July 2014, currently among 46 WTO members, to negotiate a system of tariff reductions for environmental goods. Although there was hope that these negotiations would conclude in December 2016, ministers were unable to reach agreement and the future of the Environmental Goods Agreement remains uncertain.

One reason it has likely lost steam, and why the United States hasn’t pursued this issue within its PTAs, is that environmental goods have been the center of a trade war between the United States, European Union, and China. Closely related to the renewables discussion above, these three countries have slapped tariffs and countervailing duties on one another’s environmental goods, including on solar panels, wind turbines, and biofuels. This trade war appears to be driven at least in part by domestic manufacturers of renewable energy technologies in those countries (Brewster, Brunel, and Mayda 2016) and has likely resulted in a chilling of interest in the United States in pursuing environmental goods discussions within its PTAs.

Recommendations Going Forward

Finally, our analysis and findings point to a series of policy lessons for trade negotiators in the United States and more broadly, as well as for others involved in developing and/or lobbying for linking trade and environmental policies. These recommendations are based on our core position that, when very carefully designed, trade agreements can serve as powerful tools to pursue environmental objectives. This is in part because trade agreements have stronger mechanisms for enforcement, such as dispute settlement, and are better positioned to secure adequate funds for implementation. In addition, PTAs can bring together like-minded countries, can use linkages to advance negotiation objectives, and can facilitate regulatory innovation. Further, linking trade and environmental policies makes sense. This is not only because of the intimate connection between global economic growth, including through international trade, and increased environmental degradation, but also because of the potential for international trade to enhance environmental protection through, for example, reducing barriers to trade in environmental goods. It’s not that trade agreements are a panacea for environmental problems; we recognize that the unsustainable consumption patterns that trade agreements support are arguably antithetical to solving environmental problems at all. However, when considering the socio-economic system within which we currently operate, trade agreements can and should be considered as part of a multifaceted response to environmental problems.

In this final section, we lay out the most important policy lessons from our research, which are largely transferrable across countries and environmental policy priorities.

1. Develop baseline environmental provisions for PTAs secured through domestic legislation to ensure environmental priorities are maintained over time.

US Trade Promotion Authority has been instrumental in securing a baseline of environmental action through trade agreements that ensures politically negotiated environmental priorities do not get lost over time when, for example, a less environmentally friendly administration takes office, or environmental priorities are negotiated away for seemingly more central trade issues. This approach further ensures some level of predictability for industry and can help to secure meaningful action on environmental issues that often take multiple years, or even decades, to address effectively.

Clearly, this is not something that can be easily transplanted to other countries. The US Congress has unique power in trade compared with other parliaments. Yet one case where the TPA experience could be useful is in the European Union. The European Parliament does not have a similar procedure in place to influence the negotiation process conducted by the European Commission, but it can adopt resolutions to express its views in the course of negotiations. A resolution adopted by the European Parliament recommended trade negotiators strengthen environmental provisions by providing for “recourse to a dispute settlement mechanism on an equal footing with the other parts of the agreement, with provision for fines to improve the situation in the sectors concerned, or at least a temporary suspension of certain trade benefits” (European Parliament 2010). Also, the Council of the European Union, on behalf of member states, can provide the European Commission a “negotiating mandate” with clear directives for trade negotiations. The negotiating mandate provided for the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership was similar to the TPA in many ways: it asked negotiators to provide clauses on the enforcement of domestic environmental laws, to promote trade in environmental goods and services, and to require the implementation of a set of MEAs. Parliamentarians in other countries can also put pressure on trade negotiators to address environmental issues seriously.

2. Include provisions in future PTAs that require trading partners to utilize adequate participatory democratic processes throughout the implementation phase and in developing implementing legislation prior to entry into force of the PTA.

Trading partners are often expected to implement certain aspects of their PTAs as a condition of the agreement entering into force. This can create an incentive, especially when timelines are short, to push legislation through quickly, without adequate consultation with stakeholders. Most agree this was the case in Peru following the agreement of its PTA with the United States. A confluence of factors contributed to the Bagua massacre in Peru at that time. Among these factors was a failure on behalf of the US government to recognize the Peruvian government’s disregard for democratic participatory processes in implementing the PTA through a series of 100 executive decrees, which were pushed through in as many days without adequate consultation with relevant stakeholders. This is not to say it was the fault of the United States; Peru is, of course, a sovereign state and made those decisions internally. However, governments should be mindful of power and capacity differentials between trading partners and the incentives these may create to circumvent democratic processes in less powerful countries in the name of securing access to large markets. Central to avoiding this in the future is allowing trading partners adequate time to implement such legislation through democratic participatory channels. Depending on the specific domestic political contexts in trading-partner nations, as well as the extent of the changes required by the PTA, this may involve allowing more time for implementing legislation to be in place before the PTA enters into force.

3. Build on existing MEAs, including requirements to ratify and implement MEAs.

Linking trade-related MEAs (e.g., the seven listed MEAs in US PTAs) to PTAs can be especially important in securing important environmental and trade benefits, such as protecting domestic markets from illegal timber while simultaneously protecting endangered tree species from illegal logging. The United States and others should continue to pursue MEA ratification and implementation through PTAs. These provisions should also be forward looking, including requirements to participate in ongoing multilateral negotiations, making adjustment to PTAs as new MEAs are adopted or amended, and so on. Caution should be used, however, to ensure that any PTA commitment to implement MEAs be required in the context of adequate domestic institutions, including consultation processes, in trading-partner nations. This can be done through consultations with credible NGOs and other governmental ministries/departments who have strong in-country experience in trading-partner nations, as well as through targeted capacity building provisions within PTAs themselves and any associated environmental cooperation agreements (ECAs).

4. Utilize environmental cooperation agreements under PTAs to enhance capacity building and diplomatic relations.

Trade agreements are able to secure far more political attention and implementation funding than is typically available for environmental issues. As such, utilizing ECAs to identify potential areas for environmental cooperation between trading partners can yield important benefits for environmental protection and enhancing diplomatic relations between countries, especially at the sub-ministerial level, where implementation occurs. Central to securing these benefits is support from more powerful trading partners to ensure that less powerful countries have adequate capacity to actually implement MEA-related provisions within PTAs. This might include assistance in setting up core institutions, such as ministries of environment, training national scientific authorities, and/or institutional support in developing systems of criminal penalties for violation of PTA-environmental provisions domestically. This assistance should be specific with clear targets and timeframes, and all funding should be structured as additional aid (i.e., that which is not diverted from other funding streams and/or represents a rebranding of existing aid efforts).

5. Strong action on environmental cooperation should be complemented by strong enforcement provisions, such as providing access to full dispute-settlement options for environmental provisions.

Environmental cooperation has delivered myriad benefits and allows for great flexibility in addressing environmental issues, which may be less central to core trade liberalization priorities. These provisions, which involve large cash and in-kind transfers for capacity building on environmental issues, should be pursued as win-wins for both training partners. Complementing these softer provisions, however, should be stronger enforcement measures to secure compliance with environmental provisions in trade agreements. Such provisions were long excluded from access to full dispute settlement until 2009 in the US case, and continue to be excluded from PTAs in most other parts of the globe, such as from EU PTAs. However, if environmental issues are seen as important enough to include in trade agreements, there is no acceptable prima facie rationale for excluding them from the full range of enforcement provisions. The US case suggests that important environmental benefits can be secured in doing so, without yet having to formally access the dispute-settlement provisions. Working together, effective enforcement and environmental cooperation can yield important benefits for both trade and environmental goals.

6. Monitor environmental innovations in non-US and non-EU agreements with a view toward enhancing cross-fertilization between countries.

Some lesser-known agreements include interesting environmental provisions, which may be attractive to US negotiators and others looking to innovate in this area. For example, PTAs from some Latin American countries contain innovative provisions related to genetic resources and traditional knowledge. Another example is the 2001 agreement establishing the Caribbean Community, which innovates in asking for the international recognition of the Caribbean Sea as a “Special Area requiring protection from the potentially harmful effects of the transit of nuclear and other hazardous wastes, dumping, pollution by oil or by any other substance carried by sea or wastes generated through the conduct of ship operations” (Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, supra note 42, Art. 141). Such developments should be systematically monitored and considered for adoption.