Image Gallery

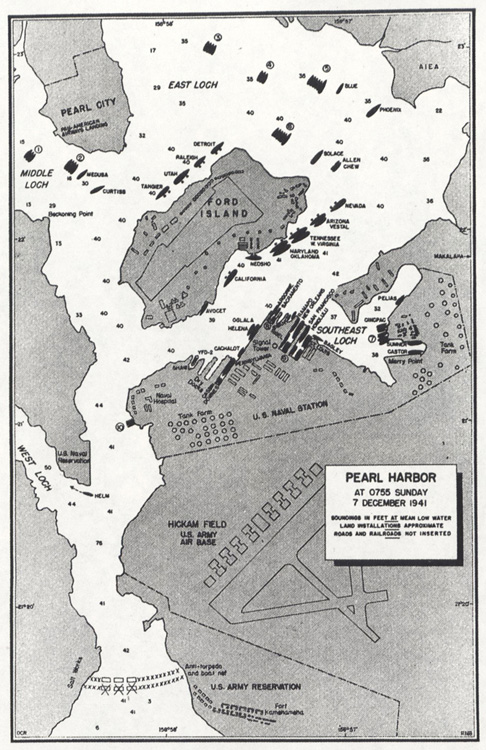

This map shows the disposition of the U.S. fleet at the start of the Japanese attack. The battleships Arizona, California, West Virginia were sunk. So was target battleship Utah. The Oklahoma capsized. The Nevada, Maryland, Pennsylvania and Tennessee were damaged. Hickam Field was devastated, its planes lined up wing tip to wing tip. Fortunately, the Japanese did not attack the vital oil tanks.

(R. M. BERISH NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER)

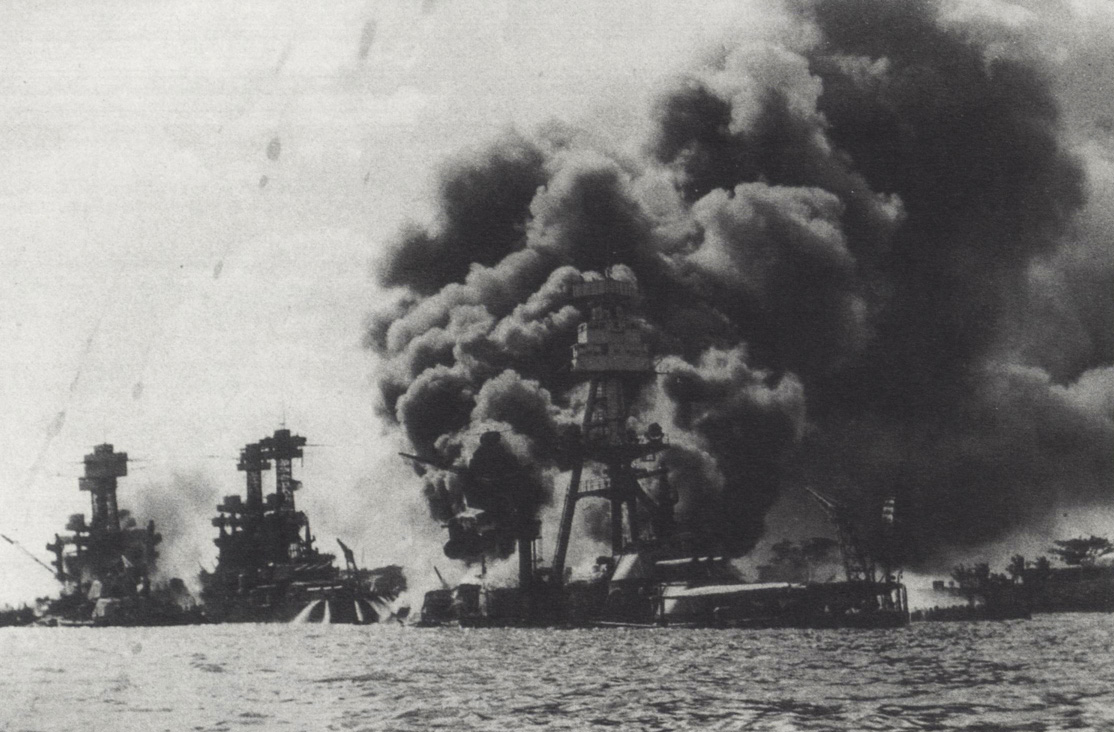

Captured Japanese photo shows torpedo tracks streaking toward moored battleships. The West Virginia and Oklahoma have been hit. Planes at Hickam Field burn in background. American naval experts had predicted that torpedoes could not be dropped from planes in shallow Pearl Harbor.

The view of ships exploding as seen from the Naval Air Station. Note the close proximity of planes to each other.

On April 9, 1942, President Roosevelt awarded CNO Admiral Stark a gold star. Roosevelt had favored the Navy over the Army in the dissemination of Magic decrypts. But the Navy failed at the crucial time to have a translator on duty to alert the commander in chief about Japanese intentions.

Secretary of the Navy Knox (left) wrote Secretary of War Stimson in January 1941 about the Navy’s fear of “a surprise attack upon the fleet … at Pearl Harbor [by]… (1) air bombing attack, (2) air torpedo-plane attack.…” Chief of Staff Marshall and Secretary of War Stimson (below) agreed and alerted the Army’s Hawaiian Command to the danger, saying: “The risk involved by a surprise raid by air … constitutes the real perils of the situation.… Keep clearly in mind … that our mission is to protect the base and the Naval concentration.”

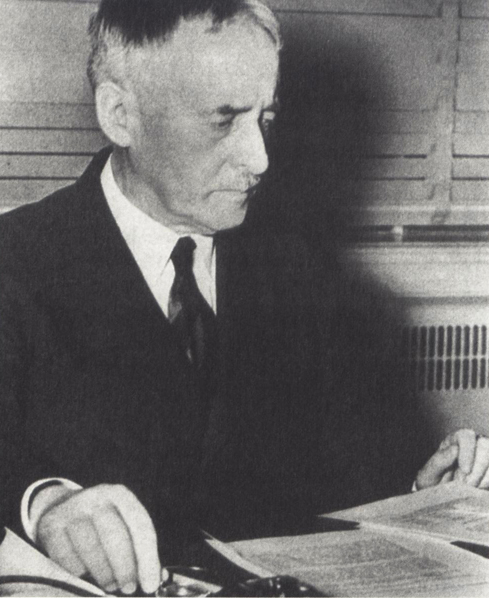

Secretary of State Hull (left) on November 27, 1941, told Stimson that further negotiations with Japan were impossible. Stimson helped draft this warning to General Short and the message was sent over Marshall’s signature. Instead of preparing for an attack, Short put his troops on minimum alert.

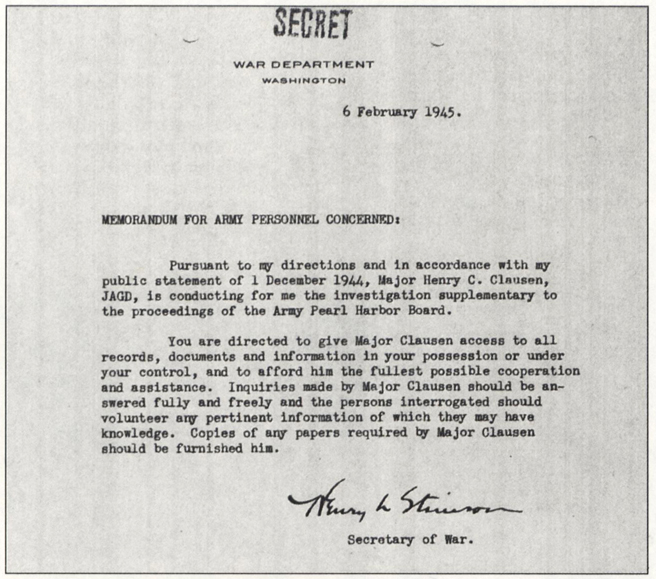

Members and staff of the Army Pearl Harbor Board. Its three general officers hated Marshall. They heard perjured testimony and reached fallacious conclusions. Henry Clausen is at the far left.

(COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR)

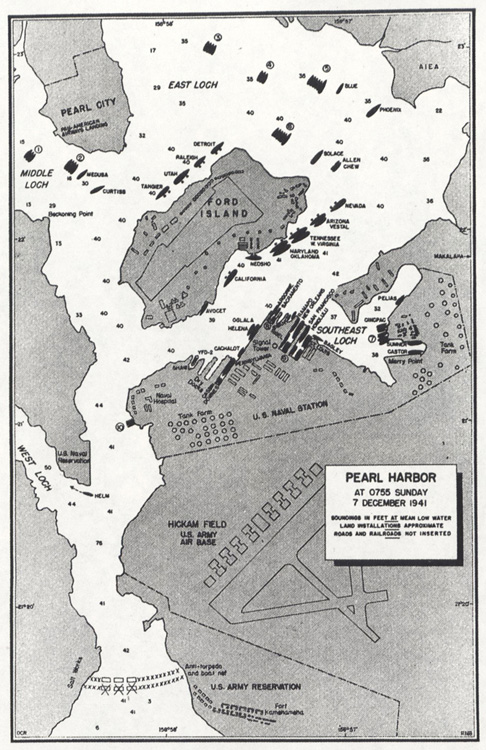

The extraordinary letter of authority that Clausen carried during his investigation for Stimson.

Brig. Gen. Kendall J. Fielder, G-2 to General Short. Fielder represented all that was wrong with the Army’s intelligence system. He was not cleared for Top Secret. He had no intelligence training. Chosen for his job because of his social graces, he shunned responsibility.

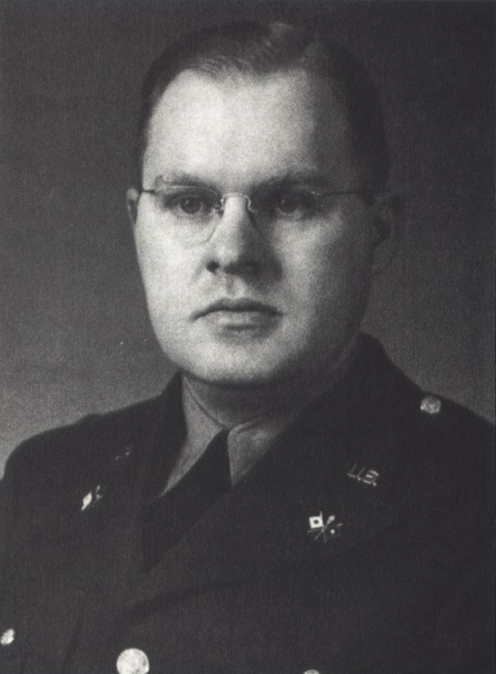

Col. Moses W. Pettigrew initiated Cable 519 advising Fielder to contact Rochefort about the Winds Code. Fielder and Short claimed they never received the message, although another G-2 officer swore he saw it on Fielder’s desk.

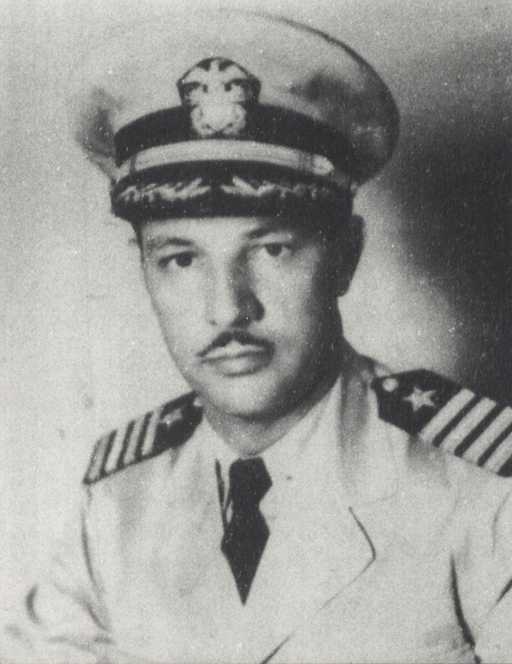

Capt. Joseph J. Rochefort, who played a major role in winning the battle of Midway, tried to mislead Clausen about how the Navy allegedly cooperated with the Army at Pearl Harbor. Rochefort also failed to exert maximum effort to break Japanese signal traffic that would have proven Pearl Harbor was a target.

(NAVAL IMAGING COMMAND)

Col. C. C. Dusenbury testified to Clausen that he received all fourteen parts of the Japanese diplomatic message at approximately midnight December 6. He did not deliver these decrypts to Marshall as had been claimed, because he did not understand their importance and “did not wish to disturb the usual recipients.” His actions lost nine vital hours to warn Pearl Harbor. Congress failed to ask Dusenbury to appear, thereby validating his affidavit to Clausen.

1st Lt. Frank B. Rowlett “did the trick” in creating the machine that broke the Purple code. He also confirmed that the fourteen-part Japanese message was in the Army’s possession around midnight, December 6. Congress never asked Rowlett to testify either.

Col. E. F. French was ordered to send a last-second warning to Hawaii on December 7. But he failed to tell Marshall that the Army radio could not reach Hawaii, so he sent the message via commercial cable.

Robert Shivers, the FBI agent in charge at Hawaii, knew about the Winds Code. He also knew the Navy was tapping the Japanese consul’s phone in Honolulu. But the Navy gave up their taps and never told Shivers, who would have continued them. (COURTESY OF FBI)

Capt. Edwin Layton was the Pacific Fleet Intelligence Officer. He falsely claimed that the warnings sent by Washington to Kimmel were too important to relay to Short. Not only did Layton “sucker the Army,” he “tried to pull a snow job” on Clausen’s investigation.

(U.S. NAVAL INSTITUTE)

Capt. J. S. Holtwick, USN, showed Clausen copies of the messages that Washington had sent Kimmel about Tokyo ordering its embassies to destroy their codes and code machines. Holtwick also confirmed that other vital Navy intelligence was not given to the Army in Hawaii.

(U.S. NAVAL INSTITUTE)

Maj. Gen. R. K. Sutherland told Clausen that before Pearl Harbor he had never seen any of the intercepts Clausen carried in his bomb pouch. As MacArthur’s chief of staff in the Philippines, Sutherland had been denied this vital information by the Navy.

Capt. W. J. Holmes of the Navy’s Combat Intelligence Unit was assigned to “plot the positions of Japanese ships based on (radio) call analysis.” His information went direct to Kimmel, who never told Short that the Navy did not know the location of the Japanese carriers just before the attack.

(NAVAL IMAGING COMMAND)

Gen. Douglas MacArthur made a special plea to Clausen, asking him to tell Stimson that “I have had to barter like a rug merchant throughout the war to get the intelligence I have needed from the Navy.” Said MacArthur: “The system as it stands is wrong.”

Brig. Gen. C. A. Willoughby, MacArthur’s intelligence chief, said the Navy gave the Army only what intelligence it selected, and only when it suited them. He said the only solution was to create “a completely joint, interlocking intercept and cryptological service—on the highest level” that would freely exchange vital intelligence. Clausen stressed this in his testimony to Congress.

The author, Henry Clausen, standing next to the wreckage of a Japanese plane in the Philippines.

(COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR)

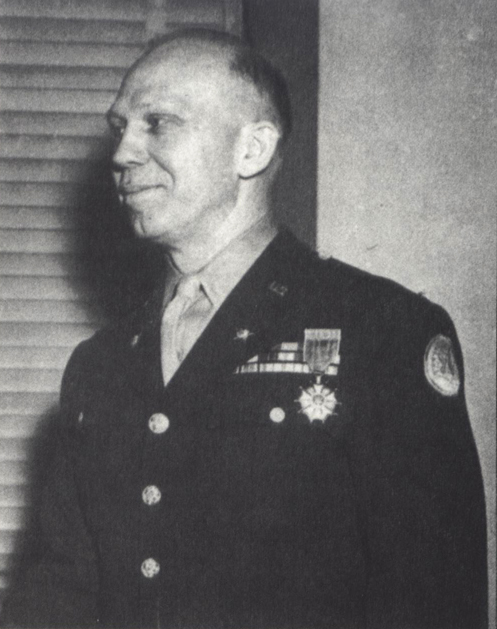

Lt. Gen. L. T. Gerow proved to be a brilliant combat commander. He knew the Navy was withholding intelligence. He believed that Short had been adequately warned to be on the alert for war.

Maj. Gen. W. B. Smith was Eisenhower’s tough and determined chief of staff. He said that Colonel Bratton could not have delivered the vital intercepts to Marshall’s office on December 6, because if he had, the material would have been given to Marshall immediately as standard operating procedure even if Marshall was at home.

Maj. Gen. J. R. Deane denied receiving from Bratton, or anyone else, on the evening of December 6 a pouch containing decrypts for Marshall. Deane also disputed the time Bratton claimed he arrived for duty on December 7.

Marshall (left) and Herron, who prepared the briefing book for Short about how to defend Hawaii. But Short read a novel, not the briefing book, and never asked Herron a single question about what his new job as Army commander in Hawaii entailed. In Herron’s estimation, Short was not fit for the command.

Col. R. F. Bratton testified falsely to the Army Pearl Harbor Board about his actions on the night of December 6. By so doing he nearly destroyed Marshall. However, Clausen discovered the truth, which Bratton confirmed before Congress, including his perjury.

Col. O. K. Sadtler was a sad, burned-out witness, who over the years reversed himself a number of times. But he testified to Clausen that he “did not see any execute message” of the Winds Code, nor did he know of such a message being received by the War Department.

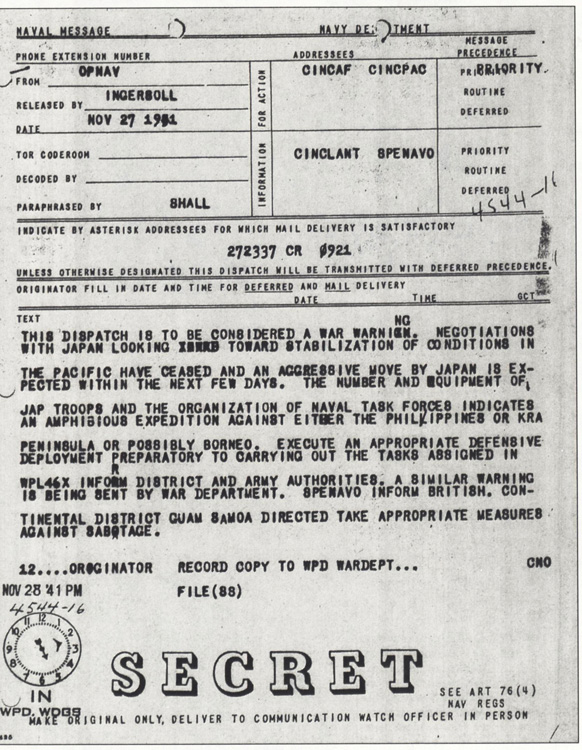

This was the Navy’s “war warning” sent to Kimmel beside the cable of the same date saying that negotiations with Japan “appear to be terminated.” It was this message that Kimmel ordered Layton to deliver personally to Short, but which Layton failed to do.

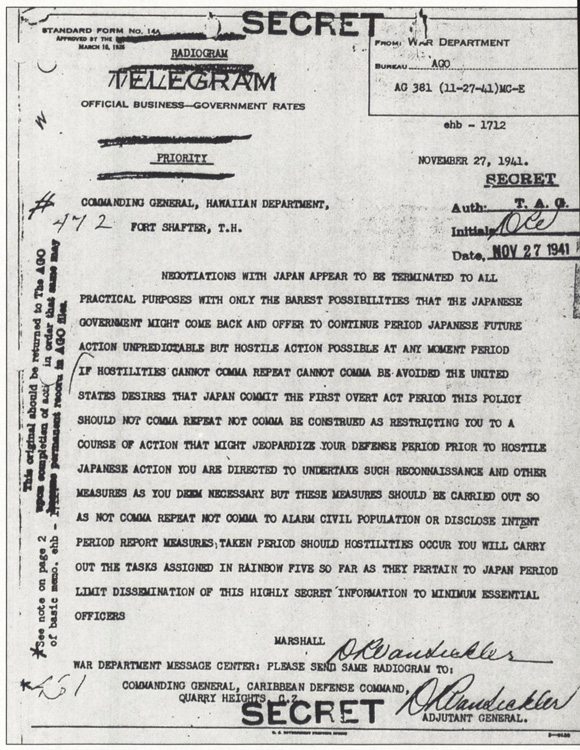

Secretary Stimson personally worked on this message in conjunction with Secretary Hull and President Roosevelt. Stimson wanted to explain in detail to Short what was going on in Washington. Not recognizing the message’s significance, Short called it ambiguous and failed to prepare for hostile action.

General Marshall (seated, center) with his General Staff. (Left to right) Gerow (War Plans), Wheeler (Supply), Miles (Intelligence), Arnold (Air Corps), Marshall, Haislip (Personnel), Twaddle (Plans & Training), Bryden (Administration). Missing: Moore (Department Chief of Staff). Marshall and Miles admitted to Clausen their roles in misleading the Army Pearl Harbor Board.

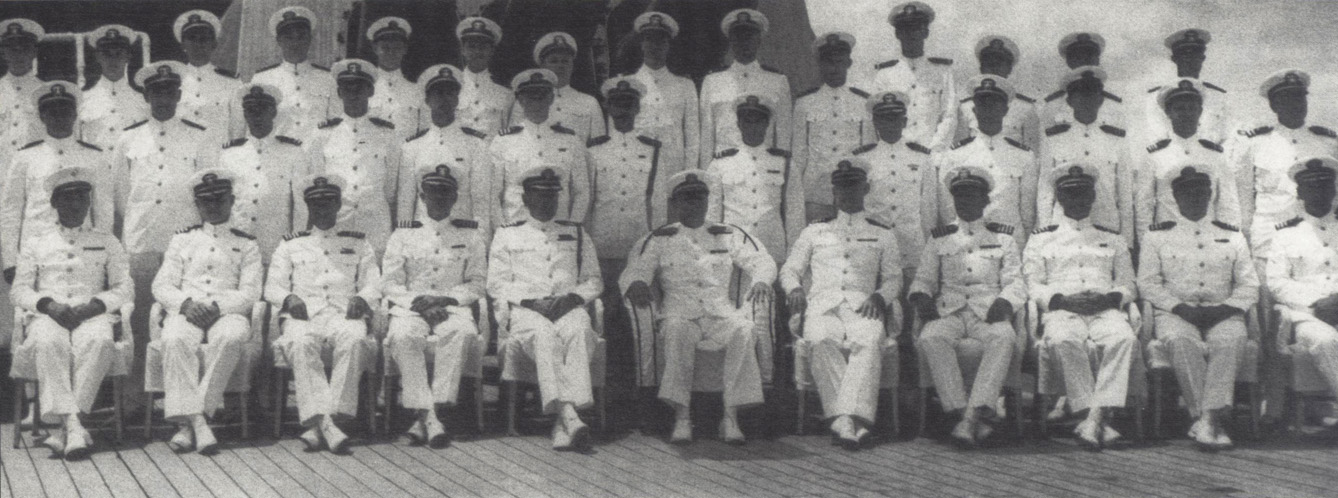

Admiral Kimmel (front row, center) and his U.S. Fleet Staff pose beneath the sixteen-inch guns of the flagship Pennsylvania (BB-38), which was damaged in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. (U.S. NAVAL INSTITUTE COLLECTION)

Battleship row at Pearl Harbor after the attack with capital ships settling on the bottom.

Secretary Stimson agreed with Clausen that the exchange of information, and consultation, between the Navy and the Army at Pearl Harbor was “inadequate.” He wrote: “It was the rule that all such information should be exchanged.…” Also, as a sentinel, Short “failed in his mission.”

Rear Adm. R. K. Turner, while head of the senior War Plans Division, tried to take over Intelligence, too, without adequate understanding of the job. He assumed and perceived without knowing, mistakenly believing Pearl Harbor was getting Purple information without asking if it was true or not. Rochefort said Turner had no use for intelligence in 1941.

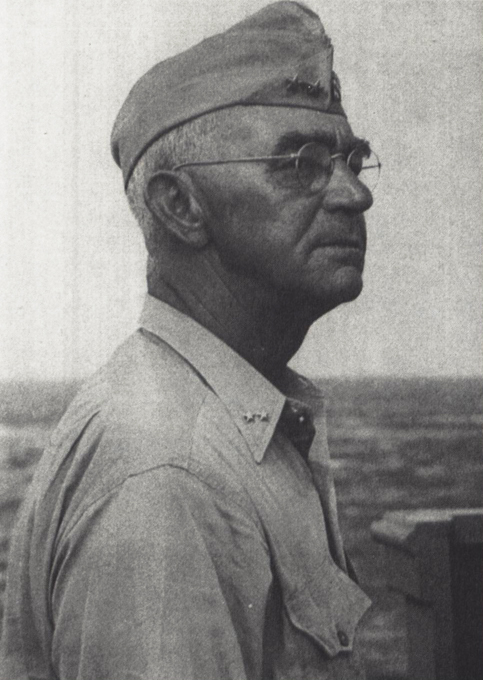

Lt. Gen. W. C. Short didn’t want the command in Hawaii and failed to study what his task entailed. He failed to follow Washington’s orders to liaise with the Navy, to conduct reconnaissance, or to use his radar, and he failed to alert his forces against attack.

Adm. H. E. Kimmel withheld vital intelligence from his co-commander, Short. Kimmel was inflexible in his convictions and expressions. He would not liaise with the Army about its state of readiness. If he had done so, he might have been a great hero.