WITH HIS FACE TO SHAG’S TAIL.

piped Grandfather, handing over a box of Malaga raisins.

grunted Pedrillo, tucking a bottle of wine and a bottle of vinegar into opposite corners of a striped saddle-bag already stuffed almost to bursting.

Tia Marta, searching wildly about for any pet objects that might have been overlooked, now came rushing forth with a scrubby palm-leaf broom. Twisting a wry face, Pedrillo shoved it under the straps of one of the loads, while Grandfather sang:

Meanwhile Pedrillo had come to grief. Setting his foot against the flank of the mule he was loading, he pulled so vigorously on the cords that cinched the pack as to burst two buttons off his trousers. As this garment boasted only four, the dilemma was serious.

The dumpy little fellow held up those two iron buttons to Tia Marta with a comical look, croaking:

“But I’ve lost my scissors,” wailed the old woman. “They slipped out of my hand just now when I was gathering up—ay de mi!—the last things from the chest, and that room in there is darker than Jonah’s chamber in the whale.”

“Hunt up a candle and look for them, can’t you?” begged Pedrillo of the children.

It was Pilarica who found, under the bench, a stray inch of tallow-dip, but it was Rafael who carried it through the house, holding it close to the floor, while Grandfather quavered:

When the scissors turned up, Pedrillo hailed them with a joyous couplet:

The buttons were sewed on with Tia Marta’s stoutest thread, and so, with song and jest, with bustle and stir and the excitement of trifling mischances, the great departure was made. On each mule, already hung with saddle-bags, Pedrillo had fitted a round stuffed frame, covering the entire back. Over this he had spread a rainbow-hued cloth and roped on baggage until the mules, in protest, swelled out their sides so that the cords could not stretch over anything more. Then Pedrillo, after vainly remonstrating with each animal in turn, had strapped another gay manta over the whole. On Peregrina, whose harness boasted a double quantity of red tassels and strings of little bells, he had piled up the baggage so cunningly as to afford a support for Tia Marta’s back, but the Daughter of the Giralda, though undaunted by the loftiness of her proposed throne, had made her own choice among the mules.

“This is mine,” she declared perversely, laying her hand on Capitana, a meek-mannered beast that stood dolefully on three legs, her ears drooping, her eyes half-closed, and her head laid pensively upon the rump of the soot-colored Carbonera.

Pedrillo hesitated a moment, then grinned and helped Tia Marta scramble up to her chosen perch, where she crooked her right knee about a projection of the frame in front with an air that said she had been on mule-back many a time before.

“Now give me Roxa,” she demanded. “Do you suppose I would leave my gossip behind?”

But Roxa had her own views about that, and no sooner had Pedrillo, catching puss up by the scruff of her neck, flung her into Tia Marta’s arms, than she tore herself loose, bounded on to Capitana’s head and off again to the ground, where she had shot out of sight under the shrubbery in less time than Tia Marta could have said Bah. But Tia Marta had no chance to say even that, for Capitana, insulted at the idea of being ridden by a clawing cat, curled her upper lip, kicked out at Don Quixote, snapped at the heels of Grandfather who was just clambering to his station on the back of Carbonera, skipped to one side, dashed by the other mules and, with a flourish of ears and tail, took the head of the procession. Thus it was that, just as the full sunrise flushed the summits of the Sierra Nevada, a lively cavalcade burst forth from the garden gate. Capitana, utterly disdainful of Tia Marta’s frenzied tugs on the rope reins, pranced on ahead, her bells in full jingle. Pedrillo, dragging the reluctant Peregrina along by the bridle, ran after, shouting lustily. Grandfather followed on Carbonera, and the children on their donkeys brought up the rear. It was not a moment for tears. Rafael, as the head of this disorderly family, was urging Shags forward to the rescue of Tia Marta, and when Pilarica turned for a farewell look, what she saw was Roxa atop of the garden wall,—Roxa serenely washing her face and hoping that the new family would keep Lent all the year, so that there might be plentiful scraps of fish.

EARLY as it was, the Alhambra children were out in force to bid their playmates good-bye.

“A happy journey!” “Till we meet again!” called the better-nurtured boys and girls, while the gypsy toddlers, Benito and Rosita, echoed with gusto: “Eat again!”

By this time Pedrillo had overtaken Capitana and, seizing her by the bridle, was proceeding to thump her well with a piece of Tia Marta’s broom, broken in the course of the mule’s antics, when Pilarica, putting Don Quixote to his best paces, bore down upon the scene in such distress of pity that the beating had to be given up. But Pedrillo twisted the halter around Capitana’s muzzle and so tied her to the tail of Peregrina. Thereupon Capitana, all her mulish obstinacy enlisted to maintain her leadership, began to bray and plunge in such wild excitement that even the decorous Carbonera danced in sympathy. Finally Capitana flung herself back with all her weight and pulled until it seemed that Peregrina’s tail must be dragged out by the roots, but, happily, the halter broke, and again Capitana, trumpeting her triumph, came to the front.

“Child of the Evil One!” groaned Pedrillo, rubbing his wrenched shoulder, while Tia Marta swayed on her pinnacle, and Peregrina cautiously twitched the martyred tail to make sure it was still on. And after Capitana’s escapades, Don Quixote still further delayed the progress of the train by a determination to turn in at every courtyard where he had been accustomed to deliver charcoal and pay a parting call.

Some of the ruder gypsy children scampered alongside, jeering at Pedrillo’s ugliness and Tia Marta’s plight, but at last even the fleet-footed Leandro had dropped back and the prolonged sound of Pepito’s bellow of affectionate lament came but faintly on the breeze. Then Grandfather, lifting his eyes to the dazzling mountain peaks from which the sunrise glow had vanished, began to sing in fuller voice than usual:

“Did you ever see the ocean, Grandfather?” asked Rafael, with a longing in his uplifted eyes that the old man understood.

“Ay, laddie, and so have you, for the first four years of your life were lived in Cadiz. Don’t you remember how the great billows used to break against the foot of the sea-wall? But I like better the waves that play on the shore at Malaga.”

And again Grandfather sang gaily, for it made the blood laugh in his old veins to feel the strong motion of a mule beneath him once more:

“I don’t remember the sea as well as the ships,” said Rafael.

“Ah, the ships!” responded Grandfather.

“It is a sight the saints peep down from the windows of heaven to see—a ship under full sail.

Carbonera and Shags had now come up with the rest of the cavalcade, which had halted at a wayside fountain to wash out dusty throats, and while Pedrillo was watering the mules and donkeys, Tia Marta, who had regained her breath after her jolting, struck into the conversation with the zest of a tongue that would make up for lost time.

“Bah! Why are you asking your grandfather about ships? He will tell you nothing but rhymes and nonsense. Did I not dwell at Cadiz for a baker’s dozen of years and what is there about ships I do not know? Live with wolves and you’ll learn to howl. Live in Cadiz and you’ll soon know the difference between the sailing-vessels, that spread their white wings and skim over the water like swans, and the battle-ships, dark and low like turtles. God sends his wind to the sailing-ship, but it’s the devil’s own engines, roaring with flame and steam deep down in the iron lungs of them, that drive on the man-of-war.”

“And my father is the master of those roaring engines,” thought Rafael with a thrill of pride, as Capitana started on again with a lunge that nearly dismounted Tia Marta, taken off her guard as she was. Falling back to the end of the train, the boy gave his red cap an impatient twirl, but its magic did not avail to show him what he so yearned to see,—Cadiz, the white city rising like a crystal castle at the end of the eight-mile rope of sand; Cadiz, the Silver Cup into which America, once upon a time, had poured such wealth of gold and gems and marvels; Cadiz, that its lovers liken to a pearl clasped between the parted turquoise shells of sea and sky, or to a nest of sea-gulls in the hollow of a rock. Just then—could Rafael’s hungry gaze have reached so far—a grim battleship was lying like a stain upon those azure waters and from her turret a stern-faced officer, with the stripes of a Chief Engineer, was watching through a spy glass a herd of conscripts, driven like cattle down the wharf to the waiting transports.

Don Quixote began to droop as the midday heats came on, and Pedrillo, still trudging along on foot, swung Pilarica up to Peregrina’s back.

“And how does our little lady like the open road?” asked the muleteer.

Pilarica had not words to tell him how much she liked it,—how strange and how enchanting every league of the way, rough or smooth, was to her senses. Under that violet sky all the world, except for the snowy mountain-tops, was green with spring,—the emerald green of the fig trees, the bluish green of the aloes, the ashen green of the olives. Every fruit orchard, every vineyard, the shepherds on the hills with flocks whose fleeces shone like silver in the sun, the gleam of the whitewashed villages, all these made the child’s heart leap with a buoyant happiness she knew not how to utter. The stranger it all was, the more she felt at home. As here and there, for instance, they passed an unfamiliar tree, it became at once a friend, and almost a member of their caravan. The hoary sycamores were so many grandfathers reaching out their arms to Pilarica; the locusts clapped their little round hands like playmates, and the pepper-trees, festooned with red berries, seemed to rival the gaudy trappings of the mules. Every turn in the road was an adventure. But the child could find no better language for her thoughts than the demure question:

“Do you think, Don Pedrillo, that we shall meet a bear?”

“Surely not,” the Galician hastened to answer; “there are no bears left in Spain to trouble the king’s highways. But if one should peep out from under the cork trees there, all I would need to do would be to fling a hammer or a horseshoe at him, and whoop! Off would amble Señor Bear, whimpering like Diego when his wife first ate the omelet and then beat him with the frying-pan. For, you see, the bear was once a blacksmith, but so clumsy at the forge that he scorched his beard one day and pounded his thumb the next, till he growled he would rather be a bear than a blacksmith, and our Lord, passing by with Peter, James and John, took him at his word. And the bear is still so afraid of being turned back into a blacksmith that if you throw the least piece of iron at him, he will run away like memory from an old man.”

“Grandfather remembers,” protested Pilarica.

Pedrillo twisted his head and laughed to see how erect the white-haired rider was sitting upon his pack.

“He is only fifty years old to-day,” he said, “but it is high time for our nooning. We’ll not squeeze the orange till the juice is bitter. Eh, señora?”

And Tia Marta replied quite affably: “You are right, Don Pedrillo. Fifty years is not old.”

“It is the very cream of the milk,” gallantly assented the muleteer, helping down first Tia Marta and then Grandfather, for their muscles were yet stiff, however young their spirits might have grown.

How glad the mules and donkeys were to browse in the shade! And how briskly Tia Marta sliced into her best earthenware bowl, the drab one with dull blue bands, whatever was brought her for the salad in addition to her own contribution of a crisp little cabbage! Pedrillo produced from one of his striped saddle-bags a handful of onions, so fresh and delicate that a Spanish taste could fancy them even uncooked, and lifting one between finger and thumb, croaked the copla:

Then Grandfather, not to be outdone, held up to general view a scarlet pepper full of seeds, reciting:

Pilarica, meanwhile, to whose guardianship Tia Marta had entrusted three hard-boiled eggs that morning, brought them safely forth from the satchel, where they had been hobnobbing with the doll, the fan and the castanets, and passed them over one at a time, to prolong the game. She herself remembered a rhyme to the purpose and sang it very sweetly to a tune of her own, dancing as she sang:

Pedrillo made sport for them, when the second egg appeared, by trying to follow Pilarica’s example, but it was an uncouth dance that his short legs accomplished in time to the copla:

But Grandfather’s verse, for the third egg, was voted quite the best of all:

Only Rafael, who had slipped away for a reason that could be guessed at, when he reappeared, by certain clean zigzags down his dusty cheeks, missed the fun, but at least he did his share in making away with the salad, when Tia Marta had given it the final deluge of olive-oil. It was a pleasant sight for the branching walnut tree that shaded their feast,—the five picnickers all squatting, long wooden spoons in one hand and crusty hunches of bread in the other, about that ample bowl where, in fifteen minutes, not even a shred of cabbage was left to tell the tale.

But the siesta was a short one for Grandfather, and he rocked drowsily on Carbonera through the heats of the afternoon, though never losing his balance. Tia Marta, who was now as bent on leading as Capitana herself, had a fearsome time of it, despite Pedrillo’s ready hand at the bridle, for the way had grown hilly, and the mule, having a sense of humor, scrambled and slid quite unnecessarily, on purpose to hear the shrieks from the top of her pack.

“In every day’s journey there are three leagues of heart-break,” encouraged the muleteer, but Tia Marta answered him in her old tart fashion:

They had covered barely a dozen miles of their long way to Cordova when they put up at a village inn for the night, all but the Galician too tired to relish the savory supper of rabbit-pie that was set before them. Tia Marta and Pilarica slept on a sack of straw in the cock-loft over the stable. Grandfather and Rafael were less fortunate, getting only straw without a sack, but that, as Rafael manfully remarked, was better than a sack without straw. Pilarica, too, proved herself a good traveller, enjoying the novelty even of discomfort. Drowsy as she was, she did not fail to kneel for her brief evening prayer:

The floor of the loft was fashioned of rough-hewn planks so clumsily fitted together that the sleepers had a dim sense, all night long, of what was going on in the stable below,—the snoring of Pedrillo, the munching of the donkeys, the jingling of the mule-bells and the capers of Capitana.

With the first glimmer of dawn, Pedrillo began to load the mules.

“Waking and eating only want a beginning,” he shouted up to his comrades of the road.

“Your rising early will not make the sun rise,” groaned Tia Marta. “Ugh! That mule born for my torment has made of me one bruise. There is not a bone in my body that hasn’t an ache of its own. Imbecile that I am! Why should I go rambling over the world to seek better bread than is made of wheat?”

“Don’t speak ill of the journey till it is over,” returned Pedrillo. “I declare to you, Doña Marta, that the world is as sweet as orange blossoms in this white hour when the good God dawns on one and all. And as for Capitana, she is fine as a palm-branch this morning, but as meek as holy water, and will carry you as softly as a lamb.”

And Capitana, hearing this, tossed her head, gay with tufts of scarlet worsted, and kicked out at Don Quixote in high glee.

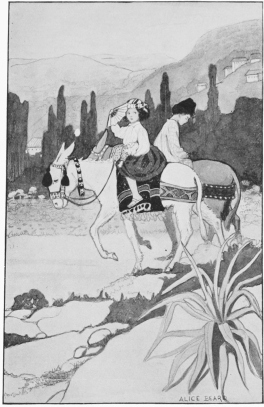

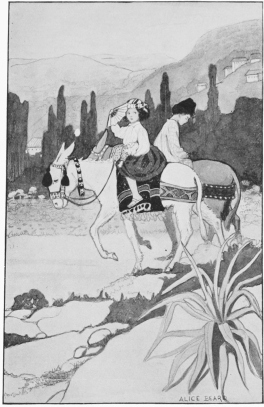

WITH HIS FACE TO SHAG’S TAIL.

IT was the sultriest afternoon since they had left Granada and the little company rode languidly, wilted under the heats that poured down upon them from that purple sky which, the Andalusians say, God created only to cover Spain. Pedrillo had slung his gay jacket across one shoulder and cocked his hat against the sun. The faithful Carbonera stepped more carefully than ever because she knew that Grandfather was dozing in his seat, and even Capitana was so far appeased by the shady olive spray that Tia Marta had fitted into the headstall as to leave that much-teased rider free to screen herself with a green umbrella bordered with scarlet, a gift from the Galician. Rafael’s red fez had no rim, so that, to escape the sun, he had turned himself about on his donkey and was riding, quite at his ease, with his face to Shags’ tail. There was no danger that Shags would run away with him! Indeed, it would have been hard to tell which of the two was the drowsier, the little gray ass with ears a-droop, or the nid-nodding boy who rode him in such curious fashion. But as for Pilarica, although she held her dainty fan unfolded over her forehead, the shaded eyes were as bright and eager as ever and missed nothing of the sights along the way. It seemed to her that she could never tire of those orchards rich in the pale gold of lemons or the ruby of pomegranates, of the reaches of sugarcane shimmering in the sun, of the rows of mulberries, the bright mazes of red pepper, the plantations of sprawling figs, the bristling hedges of cactus, the rosy judas trees and the pink almonds, the white farm-buildings all enclosed, with their olive presses or their threshing floors, in high walls set with little towers and pinnacles. Whether it was a beggar munching a cabbage stalk in the shadow of a palm, or an old woman in her doorway plaiting grass cordage, or a fruit-seller sitting beside his green and golden pyramid of melons, or a kneeling group of washer-women, with skirts well tucked up, beating out clothes in a rivulet, to each and all she flirted her fan with a coquettish Andalusian greeting.

And now she saw that they were nearing a village. They passed a group of children leading a pet lamb adorned with blue ribbons, that had evidently been taken out into the fields for a frolic and was bringing in its supper, for on the woolly back bobbed up and down a little basket filled with grass, of which Don Quixote attempted to taste. A swineherd strode down from the hills blowing a twisted cow’s-horn, and a huddle of curly-tailed pigs came scrambling after, full fed with acorns and ready for home.

An inn stood at the entrance of the village,—a low house, freshly whitewashed, half hidden in honeysuckle, with yellow mustard and sprigs of mignonette springing up on the roof between the tiles that shone green and red in the keen, quivering light. A lattice built in the open space before the door supported the wandering stems of an old grapevine, whose broad leaves made a canopy for the rush chairs and rickety tables set out beneath. As the cavalcade advanced, a line of roguish boys, hand in hand, ran down the street, barring the way, singing as they came:

“And as good a tea-bell as any,” remarked Pedrillo. “It is three hours yet to Cordova and supper. We may as well make it four. Eh, Doña Marta?”

“A sparrow in the hand is better than a bustard on the wing,” assented a dusty voice from under the green umbrella.

So they all dismounted, while the hens, calling to one another: “Tk ca! Tk ca! Take care!” scuttled before the mules and donkeys as these were led into the path of shadow east of the house, where water and a few handfuls of barley soon gave them a better opinion of life. The travellers, seeking the shade of the rustic arbor, were served by a stately, withered old dame with fig bread, made into rolls like sausages, with cherries and aniseed water. Noting a row of beehives along the garden hedge, Grandfather sang softly:

and the old dame, comprehending, brought a piece of delicate honeycomb. But from ground and trees there came such a lulling hum of insects, like the whirr of fairy spinning-wheels, that Grandfather was fast asleep before the honeycomb arrived. Rafael and Pilarica, however, saw to it that the dainty was not slighted.

“It’s only a snack, this,” apologized Pedrillo, “but we’ll fare better in Cordova.”

“Bread with love is sweeter than a chicken with strife,” said Tia Marta gloomily. “I would our journey ended at Cordova.”

“Tell us about our Uncle Manuel, please, Don Pedrillo,” spoke up Rafael suddenly. “Is he a good man?”

“Ay, as upright as the finger of Saint John. He is no common carrier, your uncle. People trust him with packets of rare value, and he is charged with affairs of importance, as the receipt and payment of money.”

“Is money important?” asked Rafael.

“Your uncle thinks so, but I tell him that many a man gets to heaven in tow breeches. Yet surely it fares ill in this world with the people of the brown cloak. There is a saint, they say, called San Guilindon, who is forever dancing before the throne of God and singing as he dances:

On that saint I, for one, shall not waste candles.”

“Does Uncle Manuel ever get angry with his mules?” asked Pilarica anxiously, for she had not travelled the white road all these days without hearing the curses of harsh voices and the thwack of heavy blows.

“Not often, Little Canary of the Moon. Don Manuel is calmer than the parish church.”

“And our Cousin Dolores?” pursued Pilarica. “Is she pretty?”

“Nothing is ugly at fifteen.”

“And our Aunt Barbara, my father’s own sister? She is lovely, of course,” asserted Rafael, the wistful look crossing his brown face.

but Doña Barbara is one of the best.”

Suddenly Tia Marta beat her fist upon the table.

“Ay de mi! That I, an Andalusian of Seville, must go to Galicia, to the ends of the earth, to serve in the house of strangers!” she cried chokingly. “How shall I bear the ways of a mistress? Whether the pitcher hit the stone, or the stone hit the pitcher, it goes ill with the pitcher.”

Then there fell upon the group a silence that awakened Grandfather.

“Is the coach rolling over sand,” he asked, “or are the wings of an angel shedding hush as he passes overhead?”

Pedrillo, who had fallen into a deep muse, roused himself with a laugh.

“We have all been dreaming,” he said in his gruffest tone. “It is because we are so near to Cordova, the City of Dreams. And yet we are three hours away. But he who goes on, gets there.”

As the muleteer was paying the modest charge, the children watched the swineherd who, in his tattered cloak and sugar-loaf hat, was passing down the street, while the pigs, without pausing to say good night, scurried off every one to his own threshold. A goatherd, too, whose cloak was faded and whose leather gaiters flapped in rags, was milking his goats from door to door.

“People of the brown cloak!” murmured Rafael thoughtfully.

It was already cooler and the beasts they mounted were refreshed as well as the riders.

“Go on your way with God!” called the old dame from the threshold.

“And do thou abide with God!” chorused the travellers.

Not until the evening was well advanced did they find themselves at last treading the stone lanes of Cordova, a mysterious, Oriental city, whose narrow streets were empty at this time except for a few cloaked, gliding figures and silent except for the tinkling of guitars. It was dark between the high walls of the houses, yet the children caught an occasional glimpse through some arched doorway, as the tenant came or went, of an enchanted patio, its marble floor and leaping fountain transformed by the moonlight into the unreal beauty of a dream. In every street at least one cavalier stood clinging to the grating of a Moorish window, whispering “caramel phrases,” or, his gaze lifted to some dim balcony, pouring forth his soul in serenade.

“Ah, this is like my Seville. So long as lovers ‘eat iron,’ we are in Andalusia yet,” sighed Tia Marta.

“I know about Murillo. He painted a whole skyful of Virgins and cherubs. Grandfather told me,” piped up Pilarica.

“Yet I warrant you he’ll eat a good breakfast to-morrow morning,” chuckled Pedrillo.

“That is my saint,” said Rafael proudly.

“Ay, and the Guardian of Cordova and the Patron of Travellers,” added Pedrillo. “His image stands high on the bell-tower yonder and it would be well for you to thank him for our good journey.”

“Does he take care of travellers on the ocean, too?” asked Rafael, remembrance of his father and brother tugging always at his faithful little heart.

But Pedrillo did not answer, for suddenly the three mules, quickening their tired pace, whisked about and made for a familiar portal.

The children let Shags and Don Quixote pick their own way through the great, dirty courtyard, crammed with carts and canvas-covered wagons, with bales, baskets and packages of all sorts, with horses, mules and donkeys and with sleeping muleteers outstretched on the rough cobblestones, each wrapped in the manta of his beast, his hat pulled down over his face and his head pillowed on a saddle.

“But their beds are as hard as San Lorenzo’s gridiron,” exclaimed Tia Marta.

“And much colder,” added Pedrillo. “Yet hear them snore! There’s no bed like the pack-saddle, after all. Here! I will tie up these friends of ours for a minute, while I take you in to see Don Manuel.”

So he hastily fastened the animals to iron rings set in a wall, on which hung huge collars and other clumsy pieces of harness as well as festoons of red peppers strung up there to dry.

Crossing a threshold, they were at once in a large room, so smoky that the children fell to coughing. An immense fireplace, where a big kettle hung by a chain over the glowing embers, occupied all the upper end. Stone benches were built into the wall on either side of this enormous hearth, and from one of them a man arose and came slowly forward.

“In a good hour, Don Manuel,” was Pedrillo’s greeting.

“In a bad hour,” returned his employer bluntly. “You are two days late and I was minded, if you did not turn up by to-morrow morning, to go on without you.”

Uncle Manuel was of robust figure and weather-beaten face. He wore, like Galician carriers in general, a black sheepskin jacket, but his was fastened in front by chain-clasps of silver. His manners were not Andalusian, for he did not embrace even Pilarica. He looked the children over keenly and not unkindly, led Grandfather to his own seat near the fire, on which the inn keeper had thrown a heap of brushwood to welcome the newcomers, and paid no attention whatever to Tia Marta, who felt herself ready to burst with rage. It was Pedrillo who found a place for her at the very end of the opposite bench and even this slight courtesy called out a noisy burst of laughter from his comrades.

“And see what a dandy he has made of himself,” mocked Hilario, who resented, in behalf of his own ginger-colored blouse and cowhide sandals, Pedrillo’s new finery.

“Dress a toad and it looks well,” taunted Tenorio, so long and lean and bony that Pilarica quietly held up her doll to get a good view of him.

“If it only had wings, the sheep would be the best bird yet,” put in Bastiano, whose voice was not merely gruff, as all those Galician voices were, but surly, too.

Tia Marta looked to see Pedrillo take vengeance for these insults, but when the flat-nosed little fellow only laughed good-humoredly, her wrath broke loose.

“The lion is not so brave as they tell us,” she snapped, squinting worse than ever because of the smoke.

And at once the rough jests of the muleteers, diverted from Pedrillo, were brought to bear on her.

“But here is a woman with a temper hot enough to light two candles at.”

“Sourer than a green lemon.”

“Long tongues want the scissors.”

“A goose’s quill hurts more than a lion’s claw.”

And still Pedrillo stood sheepishly smiling, even when Tia Marta rounded on him and on them all with the hated copla:

A growl went up from the benches, but Uncle Manuel interposed:

“And what wonder that her patience has lost the stirrup? Tired and hungry, and then baited like a bull by your rusty wits! Out to the courtyard with all of you and help Pedrillo curry the beasts.”

But Tia Marta dropped scalding tears of vexation into her bowl of puchero, though that delectable mixture of boiled meat, chickpeas and all manner of garden stuff, was already quite hot enough with red pepper and garlic.

Uncle Manuel, having seen to it that the food was prompt and plentiful, did not speak to any of them as they ate, but busied himself with adding up columns of figures in a much-worn account book that he drew from an inner pocket. When they had finished, however, he took from the inn keeper’s hand a little iron lamp, shaped like a boat, and helped Grandfather up the ladder that led to the loft. There he conducted them to two small rooms, roughly boarded off, with a low partition between them. Hanging the lamp by its ring from a nail, he opened the beds to make sure that the coarse sheets were fresh, and left them with a grave “Sleep in peace.”

The mattresses were stuffed with cornhusks of an especially lumpy sort, and that, perhaps, as well as the spell of Cordova, had something to do with the fact that they all slept restlessly, dreaming homesick dreams. Tia Marta heard the hawks wheel and whistle above the Giralda, and their faces were like the face of Pedrillo. Pilarica, nestling beside her, moved her little white feet, dancing for Big Brother, who held one hand hidden as if to surprise her with a gift when the dance was done. And beyond the partition Grandfather murmured the pet name of his twin sister who had died in childhood, more than threescore years ago, while Rafael’s red lips curved in a happy smile, for he stood with his father in the roaring heart of a swift battle-ship, which changed in an instant to a beautiful stillness, and they stood in the heart of God.

THE boy was wakened by Grandfather’s voice. The only man, lying on his back, was conversing with a spider whose long cobweb floated from a rafter.

“And it is cloudy,” announced Rafael, who had jumped up and thrust his head through an opening, that could hardly be called a window, in the wall. “How did you know, Grandfather?”

“Oh, I can feel the sky without seeing it, and this morning it is

“So it is,” assented Rafael. “I believe we are going to have a rainy day.”

Yet any kind of a day is interesting to a child, and Rafael, having quickly disposed of a cup of chocolate as thick as flannel, was soon out in the courtyard, where horses were snorting, donkeys braying, and mule-drivers, called arrieros in Spain, bawling out guttural reproaches to their beasts. They were nearly all Galicians, these arrieros, with honest, homely faces. All wore peaked caps that increased their resemblance to a company of little brown gnomes. Among them Tenorio looked more tall and gaunt than ever. He was leading out a graceful, spirited mule, sheared all over except on the legs and the tip of the tail and decorated not only with the usual red tufts and tassels and fringes, but with a profusion of tinsel tags. She carried saddle-bags, but nothing more except a copper bell as large as a coffee-pot which dangled under her neck and marked her out as the leader of the train.

Several strings of mules had gone already and others were just getting away, their bells jingling merrily and their drivers in full cry. “Arre, ar-r-r-e, ar-r-r-r e!” rent the air to the accompaniment of cracking whips and thwacking cork-sticks. The courtyard was so nearly cleared that Rafael easily made his way over to Tenorio.

“Is that Uncle Manuel’s mule?” he asked.

“Ay, his Coronela, and a pampered beast she is,” answered the Galician. “The master loves her so well that he would give her white bread and eat black himself. But what do you think of our cavalry here?”

Then Rafael saw that Pedrillo and Hilario were getting a bunch of pack-mules into line. Their loads were piled high, but they were stolid, heavy beasts, unlike the riding mules, and though they grunted under the burden and tried to get rid of their packages by rubbing against one another, they were so docile that a touch of the staff would send each to its place. But Bastiano, he of the surly voice, was having difficulties with a new mule, white and sleek, that he was lading. Blanco’s head was roped up; the two bales, having been carefully poised to make sure that they were of equal weight and would balance each other, had been slung over his back, but as Bastiano was about to lash them on, Blanco plunged and the load was tumbled to the ground.

“Ha, Tough-Hide!” snarled Bastiano. “That is the trick you would play on me, is it?”

And plucking up a large stone, he struck the animal cruelly on the side of the head.

“No, no!” cried a childish voice, and Pilarica was clinging to his arm. “You mustn’t hurt the poor mule like that. Oh, you mustn’t! You mustn’t!”

“It’s the only talk he understands,” muttered Bastiano, his lean brown face slowly flushing under the horror in those dusky eyes. “You can’t treat mules like bishops.”

“Why not?” asked Pilarica.

“The world is coming to a pretty pass when a man can’t bang his beast,” growled Bastiano, dropping the stone, while Blanco planted his four feet wide apart in stubborn resistance to anything and everything that might be demanded of him.

At that point there pierced through all the tumult of the courtyard the shrill tones of Tia Marta.

“Pilarica! Rafael! What have you bandits done with my children? Smoked sardines of Galicia that you are! Of all the rascally—”

A roar of laughter cut her sentence short.

“Here Aunt Anna Hardbread comes again to throw a cat in our faces.”

“Look out for her! Old straw soon kindles.”

“Call us names and you’ll be sorry. Though we wear sheepskin, we’re no sheep.”

“Is it true that Dame Spitfire is going with us?”

“Bad news is always true.”

“Give her civil words, then. A teased cat may turn into a lion.”

“Señora, may your joys increase—and your tongue shorten!”

“May you live a thousand years—that is, nine hundred and ten years more!”

“Ruffians!” gasped Tia Marta, as soon as she could get her voice for fury. “Cheese-rinds! If only there was a man, an Andalusian, here!”

And she glared on Pedrillo, who, more embarrassed than he had ever been in his life, was standing on one foot and scratching his bushy head.

“An Andalusian!” taunted Bastiano. “Much good that would do you. Everything with the Andalusians passes off in talk. They are all mouth. Crabs with broken claws could fight better than your Andalusian fiddlers.”

“What is Andalusia?” mocked Hilario. “A Paradise where the fleas are always dancing to the tunes played by the mosquitoes.”

Thereupon something like a diminutive battering-ram took Hilario in the stomach and he sat down so unexpectedly that he tripped up the long legs of Tenorio, who bit the dust beside him. Then Rafael, his black eyes blazing, leapt on Bastiano, who, stumbling back in his surprise against Blanco, was dealt a well-deserved mule-kick that sent him, too, sprawling on the cobblestones.

“Now they will kill me,” thought Rafael and drew his small figure erect to meet his fate like a hero. At least, if he had not captured five Moorish kings, he had brought three Galician arrieros low, and perhaps his prowess would be sung in ballads yet to be. But to his astonishment, and somewhat to his discomfiture, the courtyard rang with friendly laughter and applause, in which Hilario and Tenorio, quickly regaining their feet, heartily joined.

“Good for young Cockahoop!”

“Bravo! Bravo!”

“As valiant as the Cid!”

Even Bastiano, still sitting on the ground and rubbing his bruised shin, regarded the fiery little champion of Tia Marta and of Andalusia with an amused respect.

But Uncle Manuel, hurrying back from business in the city and expecting to find his string of mules ready and waiting, bent his brows on the scene in evident perplexity.

“It is not too late,” he said to Pedrillo, “to let you take the woman and little girl and the old man on to Santiago by railroad. My nephew may choose for himself, but I think he will like to ride with us.”

“Yes, yes!” urged the muleteers.

“We need a protector,” chuckled Hilario.

“And so do I,” cut in Tia Marta. “The boy is the only man among you. As to that Pedrillo, Don Manuel, I tell you once for all that we will not journey in his care. I would not trust him with a sack of scorpions.”

“Tut, tut!” protested Don Manuel. “One can accomplish more with a spoonful of honey than with a quart of vinegar. But if not Pedrillo, then who? The railroad is dangerous at the best, and there are several changes to be made from train to train and from train to diligence. I cannot send you on by yourselves and I can not go with you. Besides, it would be wasteful. The mules and donkeys are already provided, but the railroad will cost much money,—the railroad that has so hurt the business of us Galician carriers.”

“We are well enough off as we are,” said Tia Marta curtly, “if only we need not have speech with these sons of perdition.”

So Uncle Manuel arranged the order of march with care. He was to lead the way on Coronela, and the string of pack mules, fastened, as usual, muzzle to tail, would follow, with Tenorio, Bastiano and Hilario on the tramp beside them. The necessity of detaching, every now and then, one or another of the mules that might be carrying packages for some hamlet off the main route, made so large a number of men necessary. At a considerable distance, in order to avoid the dust kicked up by those forty hoofs, Grandfather, Tia Marta and the children were to follow, and Pedrillo was to act as rear-guard for the entire cavalcade.

The second detachment gave the first so good a start that the mule-train was quite out of sight, when our little troop rode in single file, under a pelting shower, through those narrow Moorish streets. Pedrillo paused at a mat-shop, where the prentices and their master, all squatted on the floor, were weaving the red, brown and yellow fibres of the reeds, to bargain for flexible strips of matting to wrap about Tia Marta and Pilarica, but Tia Marta haughtily declined the attention, although the rain had already run the green and scarlet hues of her umbrella into an unwholesome looking blend. Neither would she accept, for herself, his suggestion that they take refuge, till the shower be past, in the famous Moorish mosque, but she let him hurry Grandfather and Pilarica through the Court of Oranges, whose feathery palms and ancient orange trees were almost as dripping wet as the five sacred fountains, and into the strangest building of all Spain. On this gloomy morning the interior was dimmer than ever and in that weird half-light the marvellous forest of pillars,—hundreds of columns, granite, serpentine, porphyry, jasper, marbles of every kind and color,—seemed to be dreaming of those pagan temples, in Rome, in Athens, in Carthage, from which, in the days of Arab splendor, they had been pilfered by the victorious Caliphs of Cordova.

Rafael had manfully chosen to stay by Tia Marta and, when the others came out, the little fellow was having his hands full with the two donkeys and the two mules left in his charge, while Capitana, who, jealous of Coronela’s honors, had been vixenish from the start, was backing into a pottery shop and threatening with destruction a whole floorful of ruddy water-pitchers, green-glazed pots, buff plates and amber pipkins. Pedrillo sprang to her bridle and dragged her out again before she had done more damage than crush that unlucky umbrella against the lintel, so that rivulets of green and scarlet trickled freely over Tia Marta’s face, which still, despite this gallant rescue, had not the least flicker of a smile for poor Pedrillo.

And so it was day after day as the mule-train, leaving behind luxuriant Andalusia, crept across the rolling pasture lands of Estremadura, Don Quixote’s province, and the sunburnt steppes of Castile. Tia Marta regarded Pedrillo no more than if he were one of the infrequent figures they met on those lonely plains,—an elf-haired shepherd clad in the woolly skins of his own sheep, an old crone with a basket of turnips on her head, a milkmaid balancing on either shoulder a jar wrapped in leaves, a bare-legged peasant with a gaudy handkerchief twisted about his forehead and streaming down the back of his neck. To these she would, indeed, say “Good day” or “God be with you,” in response to the grave courtesy of their Castilian greetings, but Pedrillo might as well have been a gargoyle on a Gothic cathedral for all the heed she paid to his hangdog blandishments.

With Grandfather often asleep, Tia Marta always cross and Pedrillo in the dumps, the children found the advance guard more amusing. Rafael liked to push Shags forward and ride with Uncle Manuel, although, to tell the truth, he did not care much for his uncle’s talk. The practical-minded Galician was not interested in the heroes of Spain and only shrugged his shoulders when told of Rodrigo’s impulsive self-sacrifice. Rafael, on the other hand, was soon bored by details of profit and loss and by tirades against the railroads, fast doing away as they were with the time-honored mule-express. Though now and then some special business would take Don Manuel to one of the larger cities, as to Cordova, in general he served only those remote districts which the railroad had not yet invaded. Rafael would pore over his little Geography and then look off wistfully to the east, till the tawny waste was lost in the hazy blur, and dream of Toledo crowning the black cliff’s above the yellow Tagus,—Toledo, of which his father had told him so much, the ghost-city, now a mere white wraith of its once imperial self. And he was not to see Madrid, either, nor have a chance of taking off his red cap to the boy king. Still, it was grand to ride at the head of the procession and it was only when Uncle Manuel would begin to beguile the way by setting Rafael sums in arithmetic, that Shags was allowed to fall back to a more humble station.

As for Pilarica, she was the pet of the caravan and as happy as the day was long. A yellow butterfly on a scarlet poppy was enough to set her blithe heart dancing. Where Tia Marta saw nothing but endless leagues of arid, barren soil, Pilarica would find, in dips and dimples of that parched tableland, patches of sage and rosemary, wild thyme and lavender, that, trodden under foot and hoof, sent up a cloud of mingled fragrances. The carriers vied with one another in coaxing the child to ride beside them. There was not a mule in the train on whose back she had not been perched, sitting crosslegged like a little Turk between the two big bales. Tenorio would tempt her by gifts. Whenever they passed through a village, and now the poorest hamlet was a welcome sight, with its doorways full of gossiping groups, and its laughing girls, water-jar on head, clustered about the fountain, his lank figure was to be seen stooping over stall or garden-hedge buying sweeties made of almonds and honey, a red carnation or, were there nothing better to be had, a bright green beetle in a paper cage. The shabby Hilario hunted through his ginger-colored blouse and trousers all in vain for one loose copper, but his head was better stored than his pockets and he could allure both the children by starting up a droning chant of some old ballad, as this: