“THE CHILD OF HUNGER.”

As for the cunning Bastiano, he had only to crack his whip high above Blanco’s untroubled head, and a plump white donkey would charge down upon him, bearing Pilarica to the rescue.

So one blue summer day followed another until—something happened.

It was at the edge of evening, when the still heated air was musical with slow chimes from far-off convent-belfries, whose gilded crosses stood out against the sky. Uncle Manuel was rebuking Rafael for having failed to provide water enough for the needs of the day. Early in the journey—too early, in Rafael’s opinion—Don Manuel had equipped Shags with a wicker frame into which could be fitted four large water-jars, two on a side. As the caravan traversed that central plateau where water is scarce, Rafael was expected to fill the jars at every spring, well or fountain, and give the travellers, especially the tramping muleteers, drink as it was called for. At first the new responsibility pleased him, but he soon grew tired of trudging along beside Shags, who had enough to do with carrying the jars, or of begging a ride on mule-back, and of late he had grown so negligent that more than once the supply of water had been exhausted long before the lodging for the night was reached.

Under his uncle’s reprimand, Rafael flushed, but answered haughtily:

“I’m no donkey-boy.”

“Ah! You were born in a silver cradle, perhaps?” Uncle Manuel asked with quiet but stinging irony. “Are you one of those whom God created too good for honest work?”

sneered Bastiano, who had come up for a draught of water only to find one tantalizing jar after another as dry as his own throat.

Rafael, knowing himself in the wrong, could not retort, but turned abruptly, drew from the mouths of the jars the four fresh lemons he was ingeniously using as corks, handed one to Uncle Manuel, another to Bastiano and, with Shags trotting at his heels like a dog, ploughed back through the deep dust along the train. He, too, was thirsty,—how thirsty nobody should ever know; he was ashamed and wanted comfort. He would join Pilarica who, only a girl though she was, had her values in hours like this. She could always find excuses for him when he could find none for himself. Sisters were made for that. But his clouded look was lifted to mule after mule in vain. She was not with the “cavalry,” for neither Tenorio nor Hilario, who accepted the remaining two lemons as a matter of course, had seen her, as they complained, since the nooning.

Rafael was too warm and weary for extra walking and he waited for the riding party to come up, but when it came, though Grandfather, singing softly to himself, and Tia Marta, in the act of repelling Pedrillo’s humble efforts to ease her seat with the offering of a cinnamon pillow, were there, he saw no Pilarica. Don Quixote, with empty saddle, was plodding along demurely a few rods behind the rest, but when asked what had become of his little mistress, he twitched his white ears with the most non-committal air in the world.

WHILE the caravan halted, all in consternation over the loss of Pilarica, that glad-hearted little maiden was, as ever, on the best of terms with life. To be sure, the nooning had not been quite as pleasant as usual. Though the morning route had led past fields softly golden with the early summer harvest, where reapers in wide hats were wielding shining sickles, the travellers had found themselves by midday on a parched upland, neither shade nor water to be had. After their frugal luncheon of bread and cheese, flavored with onions for the muleteers and with figs for the children, everybody but Pilarica had gone to sleep in such scanty shelter from the sun as the pack-mules afforded. Pilarica had loyally stayed by Don Quixote, who, though his sides were now well rounded out, cast hardly a larger scrap of shadow than the birds of prey hovering in the burning blue, so that the child, too hot to fall asleep, had taken her doll and strolled a little away from the train. Suddenly she saw stretched out at her feet a shabby cloak, propped up a trifle by dry stalks and broken bits of brush, the brown of the cloak so like the brown of the earth that it would hardly be noticed three yards off. Under this homely tent was—of all wonders!—a baby, a really truly baby wrapped in a little white kid-skin, a baby who blinked his black eyes and gurgled drowsily as Pilarica and her doll cuddled down beside him. And there they all three slept so soundly that the bustle attendant on getting the train under way did not rouse them, while Grandfather, supposing that Pilarica was riding with her uncle on Coronela or had been tossed up by one of the muleteers to a pack-throne, himself untied the rope that bound Don Quixote’s forelegs together and chirruped to the donkey to follow Carbonera.

When Pilarica, so exhausted by the heat that her siesta lasted twice as long as usual, finally awoke, a strange, wild-looking figure was squatted close by,—a figure so tanned from the mat of shaggy hair to the naked arms and legs that it looked as if it were only a queer shape of the sunburnt soil. Pilarica, fearlessly creeping out from under the cloak and sitting upright, saw at some distance beyond this unkempt watcher a flock of goats.

The goatherd was devouring a piece of black bread which he dipped, between bites, into a cow’s-horn half full of olive oil. He jumped back as the little girl appeared and stared at her with stupid, frightened eyes.

“Good-day, sir,” said Pilarica, who knew no reason why one should not be as polite to a goatherd as to a grandee.

Scared peasant though he was, he had Castilian manners.

“Will your Grace eat?” he stammered, offering his humble fare.

Pilarica declined with a courteous gesture of her little hand, now almost as brown as his own, and the customary Spanish phrase:

“May it do you good!”

He started again at the sound of her voice, but gulped down the rest of his bread, corked the cow’s-horn, thrust it into his rough leather wallet and then went to his flock, soon returning with warm milk in a bottle. Not daring, apparently, to reach across Pilarica, he pointed to the baby.

“Oh, may I!” exclaimed the little girl in ecstasy and, gathering that kid-skin bundle into her lap, she administered the milk as best she could, singing meanwhile, over and over, one of Grandfather’s lullabies:

The goatherd, to whom Pilarica’s sweet treble had an unearthly sound, crossed himself and backed still further away.

“What is the darling’s name?” she asked, too much engrossed in her new, delightful occupation to notice the peasant’s fright.

“THE CHILD OF HUNGER.”

“The Child of Hunger,” replied the goatherd. He had a few words, at the best, and was, besides, more and more terrified in the presence of one whom he took to be a fairy. For he was but a simple-minded fellow, believing all the tales that he had heard from wandering shepherds on the windy waste or from old wives in rough-hewn chimney-corners. Whenever a lizard glided across his path, he saluted the little green creature with his best bow, for he believed that the lizard is itself so courteous that it will not go to sleep on a sunny wall without descending first to kiss the earth. When his eyes were hurting him, he would watch the swallows in their wheeling flight, for he believed that swallows know of a secret herb that cures sore eyes and that they pluck off its leaves to carry to their nestlings. He always trembled and crossed himself when he came upon even the prettiest little striped snake, for he believed that snakes never die, but when they see Death walking over the plain, looking for them, slip out of their skins and run away, growing into huge serpents with the years and becoming, in the centuries, scaly dragons that devour the flocks. This, he knew, was St. John’s Eve, when, as he had heard since childhood, from every fountain springs forth a fairy princess to spread her linen, white as snow and fine as cobwebs, out to dry in the dew. His young wife had perished of the fever a few weeks before and he could not leave their baby alone in the poor little hut of their brief happiness. So he had, while tending his flock, carried the child about with him, but the little one did not thrive. It would be better to give him to this gentle princess, who, perhaps, had come so far from her fountain to seek a playmate for that tiny fairy-baby with the golden hair and the bright blue eyes that never once winked as they looked out straight upon the western sun. What if the princess were waiting for a herd of elfin goats to bring that dainty creature milk? It would be as well for his honest Christian goats not to meet them. No harm could come to the child in the shining diamond grotto under the fountain, for the christening dews upon the little head would guard it from all evil. So the goatherd slyly picked up his coarse brown cloak and stealthily moved away with his flock, somewhat troubled in mind, for he thought Saint John might better have sent an angel than a fairy to their need, and missing so much the accustomed weight, lighter with every week, upon his arm, that he picked up a young kid and carried this for comfort.

Only the doll watched him as he went,—a high-minded doll that, as the afternoon wore by, showed no signs of jealousy, though Pilarica was utterly absorbed in her new plaything. The baby was almost as good as the doll, sleeping, or cooing, or kicking with its scrawny little legs. Once its wandering claw of a hand discovered an ear and did its best to pull that curious object off to put into the button mouth for proper investigation. It was this failure to detach its ear that finally roused the infant to wrath and it bleated as lustily as if it had been born the tenant of a kid-skin.

“Dear me!” sighed Pilarica, suddenly aware that she was weary and that a great red moon was climbing up over the edge of the world. “Where has the hairy man gone with his goats? Why didn’t he leave us some milk for supper? And when will somebody be coming for me?”

For Pilarica had the wisdom of experience. She knew that somebody always came for a little girl who was lost. For one moment a homesick thought fleeted back to her father and Big Brother and the rustling newspaper doll, and in the next she heard, not at all to her surprise, the trot-trot of Don Quixote’s hoofs and beheld that gallant ass, with Pedrillo running alongside, making over the plain toward the nooning place.

“Cry louder, Baby!” she admonished, with a little shake to which Baby instantly responded. It was really marvellous what a roar went forth upon the air, as if the kid had been transformed into a lion-cub. Clear and shrill above this remarkable accompaniment soared the ringing call of Pilarica. Don Quixote frisked his ears and tail and turned his course toward her of his own impulse; Pedrillo gave a shout of joy, and behind Pedrillo rose the halloo of Bastiano, and behind Bastiano clanged the great copper bell of Coronela.

There was a festival of greeting for Pilarica, but Baby Bunting, howling his worst, had a welcome only from Tia Marta. She gathered the brown bantling into her arms with a torrent of tender endearments and from that hour constituted herself his nurse and champion.

As the days went by, many and sharp were her quarrels with Don Manuel, who was determined that the foundling should be left at the first refuge that offered.

“Do you hope to carry this ugly tadpole on to Santiago?” he demanded at last. “Then let me tell you once for all that I will not receive it into my house. My house,” he added, not remembering to be consistent in the matter of Natural History, “is no nest for screech-owls.”

“Yah-ee!” protested the baby.

“Where’s Herod?” asked Hilario, winking at Tenorio and Bastiano, who mischievously repeated, one after the other:

“Where’s Herod?”

But Pedrillo picked up the child from Tia Marta’s tired shoulder and, dandling it skilfully, walked back and forth till the fretful cry was hushed.

They were enjoying a full midday meal at a village inn, for their lodging-place was so far on it could hardly be reached before late evening. Now that they were getting up into the hill country, where water was more plentiful and the heat not so intense, Don Manuel was pressing on at the full speed of the train in his desire that all, but especially the children, should be at Santiago for the feast of St. James. They were sitting at table in a long open room, at whose further end stood the mules and donkeys, their halters thrown over wall-pegs ingeniously made of ham-bones. Swallows flashed and called among the rafters. Pigeons with rainbow necks flew down to share the crumbs. A dog and two or three cats hunted about under the table for scraps. An enterprising hen, with a brood of fluffy chickens twit-twit-twittering behind her, bore in at the open door with the determined air of a militant suffragette and flew heavily across the room, lighting, to the children’s glee, right on Bastiano’s astonished head. The turkey and the pig, a gaunt black pig with stiff bristles, tried to join the party, but the dog, recalled to a sense of duty, promptly drove them out.

The muleteers were making merry over their favorite dish of big yellow peas boiled to a pap in olive oil, and flanked, on this occasion, by a platter of fried fish, but the children preferred an omelet tossed up in a twinkling out of the freshly laid eggs that they had helped the ventera find in the hay-scented stable. Meanwhile Grandfather was feasting them with riddles and with a treat of roasted chestnuts, singing as they munched:

And again:

At this the ventera, a dumpling of a body with roguish round eyes, held a secret consultation with Grandfather and then stood laughing at Pilarica and Rafael while he puzzled them with an entirely new riddle:

It was not until the doughnuts were spluttering in the olive oil that the children had the answer in their throats, and then it was on the way down instead of up. The carriers, even Don Manuel, came crowding about that tempting kettle, but Tia Marta, her thin face twitching, still sat on her three-legged stool at the table, crumbling her share of the loaf for the chickens and doves, and wishing she could give Roxa a shred of the fried fish. Pedrillo lingered near. Since her absorption in Juanito, as she called the child whom she had taken to her heart on St. John’s Eve, she seemed to have half forgotten her grudge against Pedrillo.

He came up to her now to show her that the baby slept.

“Angelito,” she murmured over it, touching the tiny cheek. “See, it is fatter already! I could make him well and strong, as I made the donkey. But what am I to be? A stranger in a strange land, a servant in another woman’s kitchen, with not even a cat of my own to mew to me. Never before have I been without a child to rear. There were my little sisters first, and then my blessed Catalina, and then her rosy Rodrigo—ah, that cruel Cuba!—and then those cherubs there that Doña Barbara will steal away from me. Blood is thicker than water, though it be water of tears. Ay de mi!”

“But eat, woman, eat,” gruffly implored Pedrillo. “You are giving away all your luncheon. Eat, and your trouble will be gone. Bread is relief for all kinds of grief.”

“Not for mine,” wailed the Andalusian. “Everyone knows his own sorrow, and God knows the sorrow of us all. Are the doors of Santiago so narrow that the gifts of Heaven may not enter in? Oh, this Don Manuel! This Galician with his soul shut in his account book! Growing richer every trip and grudging a few drops of milk as if he were a son of ruin with nothing left for God to rain on!”

“Patience, patience!” urged Pedrillo, his snub-nosed face so intent on Tia Marta that he inadvertently tilted Juanito wrong side up. “Did you never hear of the monk who, as he was telling his beads in his vineyard, suddenly held out his hand to see if it rained? Down flew a thrush and laid an egg on his palm. So the holy man waited, always with his arm outstretched, day after day, till five eggs had been laid, and then week after week, till they had all been hatched out and the fledglings had flown away. Then the mother-thrush, perching on the nearest fig tree, sang to the monk a song as sweet as an angel’s, so that he was well rewarded for his patience.”

“Bah! and how about the ache in his arm? But it is long since you have told me one of your foolish stories, Don Pedrillo.”

And Tia Marta, for the first time since Cordova, smiled on him.

“Ah!” murmured Pedrillo, hastily righting Juanito who was puckering for a roar. “Give the canary hempseed and you’ll see how it will sing.”

But at this critical moment Capitana, who had worked her halter free and whose softly jingling bells, as she ambled down the room, had not been noticed by the absorbed talkers, thrust her long head, with its most solemn expression, in between the two faces that had drawn so near together.

AS the road wound up into the mountains, fresh energy possessed the entire company. Even Carbonera became freakish, while Capitana was more than ever the practical joker of the train. The donkeys ran races. Don Manuel talked less of his winnings and more of the home-coming, though he still threatened Juanito, who crowed defiantly and brandished tiny fists, with the first orphanage they should reach. The rising spirits of the muleteers bubbled over in songs and witticisms at the expense of Pedrillo, whose devotion to Tia Marta, no longer forbidden, could not hope to escape their merry mockery; but that sweet-natured hobgoblin only grinned under their jesting, and Tia Marta, her tongue at its keenest, gave them as good as they sent. Grandfather and his riddles were by this time in high favor with the carriers, and Pilarica, as brown as a gypsy and as eager as a humming-bird, was very proud of the homage paid to his wild-honey learning.

And Rafael’s hurt was healing. He loved his father better than ever, better than in the days of that vague hero-worship, better than when the dear touch was on his shoulder and the dear voice in his ears,—touch and voice that he had missed with such an ache of longing. Now dreams and yearning had both melted into a constant loyalty, a passion of obedience, that was the pulse of the son’s heart. Pilarica understood. To the others he was still a sturdy, black-eyed urchin, ripe for mischief, with a child’s heedlessness and a boy’s boastfulness, but the little sister knew the difference between the teasing Rafael of the Moorish garden and this elder brother, whose care of her, though it lacked the tender gaiety of Rodrigo’s, had grown, since St. John’s Eve, into a steady guardianship.

They had been climbing for two hours, and those the first two hours after the siesta, when, even here among the mountains, the July heat was hard to bear. Springs were no longer infrequent and Shags had been relieved of his burden of jars, but Uncle Manuel, when they were nearing some stream long familiar to him, would find an excuse for sending Rafael on in advance that the lad might have the joy of discovery and announcement. So to-day it was their water-boy, as the carriers laughingly called him, who stood at a turn of the ascending road waving his broad-brimmed straw hat, long since substituted by Uncle Manuel, who had no faith in magic, for the beloved red fez.

“Water! Fresh, clear, sparkling water! Only a copper a glass!” shouted Rafael, imitating the cry of the Galician water-seller so common in the cities of Spain.

“A fine little fellow that!” commented Tenorio, whose long legs easily kept pace, on the climb, with Coronela.

Uncle Manuel tried his best not to look pleased.

“Needs training,” he said harshly. “Needs discipline. All boys do. I set him sums to work out in his head every day now as we ride.”

“Ay, and put him to figuring after supper, when he can hardly keep two eyes open,” grunted Tenorio. “You’ll wear out the youngster’s brains, Don Manuel.”

“The feet of the gardener never hurt the garden,” replied the master-carrier, who prided himself on the practical education that he was giving his nephew.

As the animals came in sight of the cascading stream, they brayed with joy. The donkeys and the riding mules plunged at once into the water, and the carriers speedily released the pack-mules so that these, too, might cool their legs in the pleasant swash of the current.

“Ah!” sighed Hilario, looking up from the bank where he had thrown himself down at full length to drink. “A brook of Galicia is better than a river of Castile.”

“It’s wetter, any way,” growled Bastiano, who had gone some distance up the stream to fill a leather bottle with the pure flow of the cascade. “The rivers of Castile are dry half the year and without water the other half.”

hummed Grandfather, while his eyes followed the play of a sunbeam in the waves.

“Did you ever hear,” asked Pedrillo of the children, as they watched Shags and Don Quixote revelling in the rill, “of that peasant called Swallow-Sun?”

“What a funny name!” exclaimed the little girl. “A thousand thanks, Don Bastiano.”

For Bastiano, who was never surly with Pilarica, had brought his bottle to her before he drank himself.

“He was called so,” continued Pedrillo, “because one day, when his donkey was drinking out of a stream in which the sun was reflected, the sky suddenly clouded over, and the peasant cried out in dismay: ‘Saint James defend us! My donkey has drunk up the sun.’ ”

It was so pleasant by the rivulet, under the shade of the great locusts, that Uncle Manuel permitted an hour’s rest.

“Don’t let us overrun the time,” he said to his nephew, and the men exchanged winks as Rafael, with an air of vast importance, consulted his watch.

Everybody welcomed Uncle Manuel’s decision. Shags and Don Quixote trotted off to a velvet patch of grass and rolled in the height of donkey happiness, their hoofs merrily beating the air. Pedrillo gathered twigs and made a bit of a fire on a broad grey rock, so that Tia Marta might heat the milk for Baby Bunting, who lay kicking on his kid-skin beside her, in the little soft shirt she had knit for him.

“This is not Castile, where I had to dig up the roots of dead bushes for fuel,” said Pedrillo, his face more comical than ever as he puffed out his cheeks to blow the flame.

“It is good to be among trees again,” admitted Tia Marta, “though the pine forests of Galicia are not beautiful like the orange-groves of Andalusia.”

“A bad year to all the grumblers in the world!” exclaimed Hilario in loyal indignation.

muttered Bastiano.

“What have you in Andalusia that shines in the sun like that white poplar yonder?” demanded Don Manuel.

Grandfather, sitting on the edge of a rock with Pilarica nestled against him, made a gesture of reverence.

“The white poplar is the first tree that God created,” he said. “It is hoary, you see, with age.

“Are there good trees and bad trees?” asked Pilarica.

“Yes,” replied Grandfather. “The trees that are green all the year round enjoy that favor in return for having given shade to the Holy Family on the journey to Egypt, but the willow, on which Judas hanged himself, is a tree to be shunned. Yet the birds love the willow, for it gives them food and shelter. Back in Estremadura, where, you remember, we saw scarcely a shrub, no birds can nest, and they say that even the wee lark, if it would visit that province, must carry its provisions on its back.”

“Are all the birds good?” asked Pilarica again.

“Almost all,” replied Grandfather.

But the swallows are best of all, because they used to build under the eaves of Joseph’s home at Nazareth and watch the face of the Christ Child at his play.”

“There was once a bird,” struck in Pedrillo, “a very saucy little bird, who ordered a fine new suit of his tailor, hatter and shoemaker, and then, quite the dandy, flew away to the palace garden. Here he alighted on a twig just outside the King’s window and had the impudence to sing:

The king, very angry, had the bird caught and broiled and, to make sure of him, ate him himself, but the little rebel raised such a riot in the royal stomach that the king was glad enough to throw him up again. The bird came out in forlorn plight, stripped of all his new feathers, but he went hopping about the garden, begging a plume from every bird he met, so that he was soon even gayer and saucier than before. But when the king tried to catch him again, he flew so fast he drank the winds and did not stop till he was above the nose of the moon.”

“Bah!” said Tia Marta. “Stuff and nonsense”

“Rubbish!” chimed in Bastiano. “Pedrillo must have been taught to lie by a serpent descended from the snake of Eden.”

“And what, pray, do you know about it?” snapped Tia Marta, turning most inconsistently against her fellow-critic, “you who are standing off there solitary as asparagus or as that ill-tempered old rat who made himself a hermitage in a cheese,—You who couldn’t tell a story half as good, no, not for a pancake full of gold-pieces!”

“What a scolding deluge is this! It froths and fizzes like cider. It’s a pity there are not stoppers enough for all the bottles in the world,” retorted Bastiano.

“Come, come!” interposed Grandfather. “Stabs heal, but sharp words never. There is a cool breeze springing up. Thank God for his angel, the wind!

The little fire on the rock flared up in the gust, and the children, who, having borrowed all the hats in the company, had ranged them in a row and were trying to outdo each other in jumping over every hat in the line and back again without a pause, came panting up to watch the flame.

“Sing us the fire songs, please, Grandfather,” coaxed Pilarica. She brought the old man his guitar and as the withered fingers moved over the strings, even Don Manuel drew near to listen.

“Ugh!” interpolated Tia Marta, who had burned her finger. Grandfather’s eyes twinkled.

“Don’t forget the one about the charcoal,” prompted Rafael.

“We stack up pine cones for fuel in our Galician cellars,” observed Uncle Manuel. “It is only the stupidest peasants who cut down our splendid chestnuts for firewood, burning their best food.”

“But there is no end to his wisdom!” gasped the admiring Hilario. “Only two more,” smiled Grandfather.

“Those are the sparks,” interpreted Pilarica.

“That’s the smoke,” expounded Rafael.

“And now do let him rest,” commanded Tia Marta, folding her bright-hued Andalusian shawl into a pillow for the white head. “Lie down there by Juanito and be quiet till the start. These children, little and big, would keep you playing and singing for them till the Day of Judgment. It’s your own fault, too. If you make yourself honey, the flies will eat you.”

While Grandfather dozed, Pedrillo put out the fire and tried to talk with Tia Marta, but she perversely turned her back.

mocked Tenorio, but Pedrillo, nothing daunted, set to making Rafael a popgun. This he did very deftly by cutting a piece of alder half as long as Pilarica’s arm, which he measured with great gravity from wrist to elbow. Drawing out the pith, he fitted into the alder tube a smaller stick to serve as ramrod, and everybody fell to searching for bits of cork, pebbles, pieces of match, anything that would do for bullets. Uncle Manuel went so far as to contribute a sharp-pointed pewter button.

So was Rafael, all unconsciously, armed for his great adventure.

FROM time to time, while our travellers took their ease in the locust shade, other wayfarers came toiling up or down the steep and stony road and paused to drink at the stream. There were two strings of pack-mules during the hour, the muleteers passing the laconic greeting: “With God!” A freckled lad of a dozen years or so, in charge of a procession of donkeys nearly hidden under their swaying loads of greens, was too busy for any further salutation than an impish grimace at Rafael. There were boorish farmers, doubled up on side-saddles. There was a group of rustic conscripts, ruddy-cheeked, saucer-eyed, bewildered, their little all bundled into red and yellow handkerchiefs and slung from sticks over their shoulders. There was a village baker with rings of horny bread strung on a pole,—bread eyed so wistfully by a lame dog who was tugging along a blind old beggar that Uncle Manuel, quite shamefaced at his own generosity, gave Rafael a copper to buy one of those dusty circlets for the two friends in misfortune.

Here it was the children first heard the unforgettable squeal of a Basque cart. Far up the mountain road sounded vaguely a groan, a rumble, and then a rasping screech that startled Grandfather out of his nap and made Tia Marta, snatching up Baby Bunting, scramble to her feet in consternation. When at last the yoke of stalwart oxen, with a strip of red-dyed sheepskin draped above their patient eyes, came lumbering down the difficult descent into view, the children saw that they were attached to a rude cart, whose wheels were massive disks of wood, into which a clumsy wooden axle-tree was fitted, grating with that uncanny squeakity-squeak at every revolution. The cart had a heaping load of cabbages, together with a bundle of fodder for the oxen and a basket of provision for the driver, who plodded along beside them.

“What a hideous, horrible racket!” scolded Tia Marta, while Juanito, jealous of this unexpected rival, screamed his lustiest.

“Hush, baby, hush!” soothed Pedrillo. “Hush, or the Bugaboo will get thee. Nay, Doña Marta, that is the music of my homeland. We all love it here. The oxen would not pull without it. Besides, it scares away the wild beasts of the mountains and puts even the Devil to flight.”

“And see those cabbages, the bread of the poor,” exulted Hilario. “Ah, there is no dish in all Spain so good as our Galician cabbage-broth.”

The wail of the cart, that jolted by without stopping, was yet in their ears, when Pilarica, who was still gazing after it, began to dance with excitement.

“O Rafael! Rafael!” she cried. “Come and see! Come quick! These are the wonderfullest people yet.”

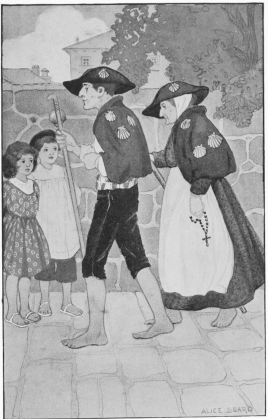

She had caught sight of a band of pilgrims on their way to Santiago, to the shrine of St. James, whose festival falls on July twenty-fourth and still attracts devotees from all over the Peninsula, especially the northern provinces and Portugal, and even from beyond the Pyrenees. It was a picturesque group that came footing it bravely up that hot, rocky road. The bright sunshine brought out the crude colors of their homespun petticoats, broidered jackets, blouses, sashes, hose. The women’s heads were wrapped in white kerchiefs, but over these they wore, like the men, broad hats whose rims were caught up on one side by scallop shells. Notwithstanding the mid-afternoon heat, most of them kept on their short, round capes, spangled all over with these pilgrim shells, sacred to St. James. Their staffs, wound with gaudy ribbons, had little gourds fastened to the upper end. Some carried leather water-bottles at their belts, but they had no need of knapsacks, for food was given them freely all along the route and, if charitable lodging failed, the pine groves made fragrant chambers.

The pilgrims paused to drink at the cascade, and the children, while careful not to intrude, ventured, hand in hand, a little nearer. One man came limping toward them and seated himself on a stone. He was making the pilgrimage barefoot, as an act of devotion, and a thorn had run itself into his heel.

PILGRIMS ON THE WAY TO SANTIAGO.

“May I try, sir?” asked Rafael, as the stranger’s lean fingers fumbled rather helplessly at the foot, and instantly, with a twist and a squeeze and an “Out, if you please,” the boy had drawn the thorn. To prevent the embarrassment of thanks, Rafael turned to his sister.

“Sing the riddle, Pilarica,” he directed, and the little girl, Grandfather’s ready pupil, piped obediently:

The dreamy-eyed pilgrim paid no heed to the rhyme, but dropped to his knees, bowed his head to the ground and kissed Pilarica’s little worn sandal.

“For the sake of Our Lady of the Pillar, whose blessed name you bear,” he said, detaching from his cape—which, in addition to the scallop shells, was studded over with amulets of all sorts—a tiny ivory image of the Virgen del Pilar and pressing it into Pilarica’s hand. “Even so she keeps her state in her own cathedral at Saragossa. Ah, that you might behold her as she stands high on her jasper column, her head encircled by a halo of pure gold so thickly set with sparkling gems that the dazzle of their glory hides her face in light!”

A jovial old peasant, whose costume might have been cut out of the rainbow, pushed him rudely to one side.

“Well do I know Our Lady of the Pillar,” he boasted, “and her jewelled shrine in Saragossa, for I am of Aragon, the bravest province in Spain.”

“My father used to live in Saragossa,” volunteered Rafael, with the shy pride that always marked his mentions of his father. “He has told us of Our Lady of the Pillar and of the leaning tower.”

“Ah, that swallow is flown. The tower fell a matter of eight years back. My old wife and I can give you a song about that, for this little honey-throat is not the only musician in Spain. Ay, you shall hear what we old birds can do. The children sing this song, you understand, in dancing rows, one row answering the other, but that wife of mine is equal to a baker’s dozen of children. Look at her! Is she not devoted to the good Apostle to trudge all this way on foot? A long, rough way it is, but many amens reach to heaven. Come forth, my Zephyr! Waft! Waft!”

And he began to troll as merrily as if he had not a sin in the world, cutting a new caper with every line:

Out of the applauding cluster of pilgrims a very stout but very robust old woman, her skirt well slashed so as to display her carmine petticoat, came mincing to meet him, taking up the song:

An ironic laugh broke from the listeners, while the husband, flourishing legs and arms in still more amazing antics, caught up the response: