RACING TO SPACE

TREK’S FICTIONAL STARSHIP EMBARKED ON ITS JOURNEY WHEN NASA’S MISSIONS DOMINATED THE HEADLINES—FOREVER LINKING THEM BOTH

BY JEFFREY KLUGER

In 1976 Star Trek cast members join NASA officials for the unveiling of the space shuttle Enterprise, named for the iconic fictional spacecraft.

THE IMAGINARY EARTH OF STAR TREK WAS ALWAYS A NICER PLACE than the real Earth—especially the Earth as it was when the series was born. The starship Enterprise embarks from a united planet, which is itself part of a galactic federation that sends its explorers out into the universe. The Earth of the 1960s was a place on a knife edge, with the U.S. and the then–Soviet Union vying for global domination while hoarding enough nuclear weapons to reduce the planet to char. The space race itself was just one more expression of this very bitter conflict.

But give the old Cold Warriors this: when it came to space, they talked a good game. We would not militarize low-Earth orbit, we promised. We would not militarize the moon. In 1966 we negotiated an international agreement that went by the shorthand name the Outer Space Treaty but was formally known as the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies. Whatever it was called, it had a few simple rules, the most basic of which was: no cosmic combat.

While plenty of people were fooled by all the happy talk, however, not everyone was. The space race, while bracing, was a thing conducted by both sides in a state of mortal fear. The Soviets got out to an early lead, launching Sputnik, the first satellite, atop their fearsome R-7 missile, a rocket that was far more powerful than anything in the U.S. arsenal and that would be just as happy to deliver a warhead to Toledo as a satellite to space. The U.S. responded to this muscle-flexing quickly, launching its first astronauts aboard the Redstone, Atlas and Titan boosters—weapons of war all. The astronauts who flew atop the Titans could actually feel the guidance system wagging the nose of the missile left and right, vainly sniffing for targets on the ground even as it was being aimed toward space.

Yet there was no denying that space would always be something more than just another arena of combat. There was the beauty of it, yes, the dreaminess of it. But there was also the enormity of it. Human beings, perverse animals, measure their power by their ability to break things. A single bomb can destroy a city. But set one of them off in space? A popgun. Space made us feel powerful and fearful and impossibly humble all at once, and we didn’t know quite how to reckon with such a mix.

And into that swirl stepped Star Trek. It would be too much to say that the show was a cultural phenomenon from the start; it wasn’t. It was the most-watched program in its 8:30 time slot on the evening the first episode aired—Sept. 8, 1966. That was a victory for the home network, NBC, but the win came cheap: in the same hour, CBS was airing the shopworn sitcom My Three Sons. Star Trek’s reviews were mixed—and some were dismal. The Boston Globe called the show “clumsily conceived and poorly developed.” The Houston Chronicle described it as “disappointingly bizarre.” The New York Post fretted that the whole concept was just too intellectual. “One may need something of a pointed head to get involved,” wrote the paper’s critic.

But Star Trek had other things going for it that the critics overlooked. It had timing, for starters. On the very morning those reviews were coming out, NASA was preparing for the launch of Gemini 11, the 15th American spaceflight and one with grand plans—not the least being the distance the astronauts would travel from Earth. According to the New York Times’s front-page story, the spacecraft would “swing out farther into space than man has ever ventured—865 miles.”

If you loved the space program and you watched that first episode of Star Trek—and plenty of Americans did both—the contrast was impossible to miss. The starship Enterprise could range across the galaxy, which is 621 quadrillion miles from one end to the other. The spaceship Gemini could go for 865 of those miles.

“When I was born, Sputnik had just been launched,” says Alan Stern, principal investigator for the New Horizons mission, which achieved the first-ever flyby of Pluto, in July 2015. “At the time, 200 miles in altitude was the state of the art. Star Trek could have made that feel unimportant, but somehow it didn’t. Even early on, it was more of a challenge to our better selves.”

The show’s curious ability to pose that challenge wasn’t thanks to its sets or its costumes or its special effects, which were hopeless by modern-day standards and cheesy even by 1966 standards. Compare the visual style of the series with the dazzle of 2001: A Space Odyssey, which hit movie theaters just two years later. Not even close. But while 2001 was eye-popping, it was also ponderous—space travel as undergraduate philosophy seminar. Star Trek was space travel as uplift.

“It was all in the scripts,” says Stern. “It was all in the stories. The future that Star Trek depicted seemed like a technologically plausible one, and the characters were dealing with real issues, ones we could understand.”

One of those issues—acutely apt in the era in which the show was born—was human tribalism. In the 1960s, television was integrating, though slowly, grudgingly. The drama I Spy, which premiered in 1965, paired Robert Culp and Bill Cosby as wisecracking intelligence agents—a black-white partnership that was revolutionary at the time. The Man from U.N.C.L.E., which began the year before, was in some ways more daring, teaming an American secret agent with a Soviet sidekick. Beyond that, though, there wasn’t much.

Star Trek famously exploded that cautious incrementalism. Yes, the captain was a white American male. But the ship was peopled by a multi-culti festival of skin shades and nations, crew members from Russia and Africa and Asia and Scotland and, just in case the entire color wheel of humanity wasn’t enough, a Vulcan. The pioneering inclusiveness of Star Trek was the polar opposite of the with-us-or-against-us, U.S.-Soviet nationalism that defined the real space race.

“I wasn’t even born when the first Star Trek aired, but I know it resonated,” says Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti, who flew a 200-day mission aboard the International Space Station from November 2014 to June 2015, breaking the single-mission longevity record for a female astronaut. “It was at the end of European colonialism, and here you have an international crew that talks about its Prime Directive—the idea that you should go and explore but you shouldn’t interfere with a culture to the point that you derail its development. Those things were a statement on what was going on in the world.”

It was a statement that spoke loudly to Cristoforetti. She did not tumble for Star Trek until the 1990s, when she was in high school—but she fell hard. “I came to the U.S. when I was a student, at 17,” she says, “and I thought I was in paradise because Star Trek was on twice a night. My host mother in Minnesota knew she had to give up the TV for those two hours.”

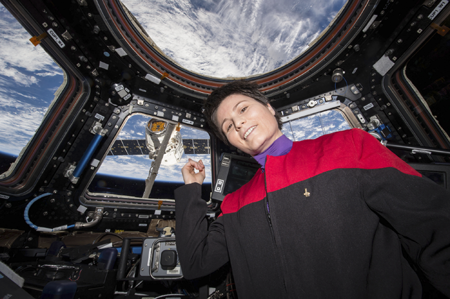

Cristoforetti never shook off the spell. When she found herself in space in 2015, on the 20th anniversary of the premiere of the Star Trek: Voyager spinoff, she posed in the station’s multi-windowed cupola in the Starfleet uniform of the show’s Capt. Janeway, the first woman in the lead role of starship commander in the history of the series. A Star Trek costume is not something you have on hand in orbit unless you’ve planned it for a while.

Star Trek did not just have its effect person by person, child by child, as it did for Stern and Cristoforetti. Years after the first series ended and well before all of the movies and spinoffs were created, it had already seeped into America’s national consciousness. By 1972, the Apollo program had ended, strangled for lack of funds. But the fact that we’d been to the moon could not be changed, and the fever dream of an even grander future, partly sustained by a vision like Star Trek’s, could not be cooled so easily.

In 1976, NASA rolled out the first of what would eventually be six new space shuttles. That initial model was not intended to fly in space; rather, it was a trial vehicle that would be used to wring out problems and design flaws before the first vehicle actually did go into orbit. Nevertheless, it was a beautiful piece of engineering, and like any good vessel it needed an equally beautiful name. On September 3 of that year, White House senior economic adviser William Gorod sent a memo to President Gerald Ford, making it clear what his choice should be.

“NASA has received hundreds of thousands of letters from the space-oriented ‘Star Trek’ group asking that the name ‘Enterprise’ be given to the craft,” he wrote. “This group comprises millions of individuals who are deeply interested in our space program. Use of the name would provide a substantial human interest appeal.”

Other staffers weighed in, agreeing with the idea. And although they also cited the deep roots the principle of enterprise has in the American economic system and the multiple times the name has been used for Navy vessels, the real reason was inescapable. The president took his advisers’ advice, and on September 17 the new ship was rolled out of its Palmdale, Calif., hangar and formally named. Much of the cast of the original series, including DeForest Kelley, George Takei, Nichelle Nichols and Leonard Nimoy, were in attendance.

It was Nimoy more than any of the others—more even than William Shatner, who played Capt. Kirk—who was important to have on hand for the event, because it was Nimoy’s Mr. Spock character that most deeply touched the culture. The complexity of the Spock character was all about contradiction—the push-pull between his logical and almost mystical sides. The 1960s were a time of widespread, if sometimes faddish, spirituality. But there was a binary—almost elitist—edge to the new enlightenment. To embrace spirituality you had to reject the empirical, the scientific, in search of something higher.

NASA’s engineers and astronauts, however—empiricists all—were nothing like that. Many were more like Spock—and in some ways further along than Spock, with spiritual beliefs and scientific knowledge existing comfortably together. Buzz Aldrin performed a quiet communion in the Apollo 11 lunar module on the surface of the moon. The Apollo 8 astronauts read Genesis back to Earth while orbiting the moon on Christmas Eve in 1968. Charlie Duke, Apollo 16 moonwalker, returned to Earth and a few years later became a deeply devoted Christian. The most famous words spoken at the moment of John Glenn’s first liftoff came from backup pilot Scott Carpenter, who intoned over an open mic, “Godspeed, John Glenn.”

Certainly, a mere television character had little if any role in making those things happen, and Carpenter spoke his words four years before Star Trek ever aired. But it’s not too much to say that a television character gave pleasing shape to the multiple dimensions—the profane and the divine—in all of us.

“I think Spock was the first embodiment of an alien persona that human beings ever took seriously,” says Stern. “He was half-human, and that was part of the tension: logic versus devotion.”

When Nimoy died in 2015, Cristoforetti, still aboard the International Space Station, tweeted down another picture of herself in the cupola, this time gazing out of the window while making Spock’s signature “Live long and prosper” gesture. Quoting Capt. Kirk eulogizing Spock in the Star Trek movie The Wrath of Khan, she wrote: “ ‘Of all the souls I have encountered . . . his was the most human.’ ”

The International Space Station, for now, is our starship Enterprise. Yes, it travels in circles instead of across the galaxy, and, yes, its maximum speed is 17,150 miles per hour instead of warp speed, which is faster than light. But nothing changes the ambition and scale of the thing—larger than a football field, which may not be Enterprise-size but is still more spaceliner than spacecraft. And nothing changes its collaborative ethos: the 15 nations that contributed hardware and labor to the construction job, the 222 different people from 18 countries who have spent time aboard.

In March 2016, NASA astronaut Scott Kelly and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko returned to Earth after spending a year aboard the station. Training together for two years and flying together for one year, they were far beyond the old Cold War enmity of their parent nations, even in a time of increasing U.S.-Russian tension.

“I like to call him my brother from another mother,” Kelly said about Kornienko before they left Earth together. That is both a peaceable and practical model for spaceflight, and it is one that will probably endure.

“I think that the eventual human presence on Mars will be multinational too,” says Cristoforetti. “Just like with the station, there will always be different countries that can bring different things to the table.”

When that interplanetary presence will occur, and whether it will reach beyond Mars and deeper into the galaxy, is unknowable for now. In some ways, we were spoiled by the Apollo era, when we simply willed a half-dozen lunar landings into being—and did it on a self-imposed deadline. But the accomplishment, grand as it was, may have been strangely premature.

“Arthur C. Clarke said that the 1960s were an anomalous decade,” says Stern, “plucked out of the 21st century and plopped into the 20th.” Once the U.S. won the space race, the old century could play out at its sleepier pace.

That may well be true, but Star Trek, which served as part of the soundtrack of that thrilling era, was no anomaly. Grand explorations have been part of our behavioral genome since our species first emerged. The tales we tell ourselves—in literature, in film, on television—help satisfy that impulse and help prod us to embark on those voyages for real.

In 2015 Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti poses in the International Space Station wearing a Trek-like uniform. A pending fan-produced Star Trek film has since recruited her for a role.

President Ronald Reagan, in a tan suit, waving from a platform by the prototype space shuttle Enterprise, joins nearly half a million spectators at Edwards Air Force Base in California to celebrate the landing of the space shuttle Columbia on July 4, 1982.

In 2014 NASA engineers unveils an artistic rendering of a future spacecraft for hypothetical warp speeds, an idea the agency has been investigating since 2010. The illustration was inspired in part by artist Matt Jefferies’s original 1965 design of the starship Enterprise.

Space exploration today is an international cooperative. On Jan. 21, 2016, astronaut Scott Kelly of NASA (left) and cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko of Roscosmos (right) mark their 300th consecutive day in space aboard the International Space Station.

Jeffrey Kluger, a TIME editor at large, co-authored Apollo 13 with astronaut Jim Lovell.