TAKING KLINGON TO COURT

THE ALIEN LANGUAGE HAS SPARKED A VERY EARTHLY BATTLE

BY ALEX FITZPATRICK

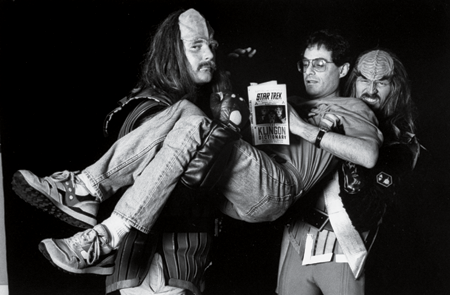

Marc Okrand, carrying his Klingon Dictionary (published in 1985), is carried by men dressed as Klingons at the National Air and Space Museum in 1992.

WHO, IF ANYBODY, OWNS THE KLINGON language? That question, once the sole domain of extraordinarily geeky copyright scholars, has suddenly spilled into the fore—underscoring the surprisingly influential position of this made-up tongue.

It’s all because of a legal battle over a Star Trek fan film called Axanar. Axanar’s creators have raised more than $600,000 from fellow Trekkers to make a feature-length movie set in the Trek universe. But they were sued by CBS and Paramount Pictures, which claim the rights to essentially all things Trek.

Heading into summer 2016, Paramount and CBS were said to be dropping the case—but not before one of their grievances set off a firestorm among Trek fans and legal experts. As part of the suit, the companies argued that the Klingon language, created by linguist Marc Okrand for 1984’s Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, is among Star Trek’s copyrighted elements. That is no small claim.

Over the three decades since its creation, Klingon has morphed from a few lines uttered in a science-fiction franchise to a global phenomenon. Klingon is the most widely spoken fictional language in the world, according to Guinness World Records. There are multiple Klingon-to-English dictionaries, including a handy abridged version, How to Speak Klingon: Essential Phrases for the Intergalactic Traveler. Some of the most celebrated works of the English language, such as Shakespeare’s Hamlet, have been translated into Klingon. A handful of die-hard fans even speak the language fluently, declaring Qapla’!, or “success,” when they have achieved such mastery.

Devotees of fictional languages argue that if CBS and Paramount were afforded broad Klingon copyright protections, it could have a chilling effect on all that creativity—not to mention leave a sour taste in the mouths of Trek’s biggest fans. “Klingon, like any other spoken language, provides tools and a system for expressing ideas,” reads an amicus brief filed in the case by the Language Creation Society, a nonprofit dedicated to “conlangs,” or constructed languages. (The brief is, amusingly, dotted with Klingon expressions impossible to reproduce in the English alphabet of this terrestrial publication.) “No one has a monopoly over these things, effectively prohibiting anyone from communicating in a language without the creator’s permission.”

Indeed, some experts say that copyright law does not protect rules and processes such as languages. “My instinct, based on copyright doctrine, is that you cannot copyright the Klingon language as a whole,” says Shyam Balganesh, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. Balganesh says the studios would have a more plausible case if Axanar had lifted specific Klingon dialogue from existing Star Trek TV episodes or films.

Whether a language enjoys copyright protection has implications even for those who may never read a Klingon version of The Epic of Gilgamesh (also available). A similar question was at the heart of Silicon Valley’s fiercest legal battle so far this year. In the case, database firm Oracle accused Google of copyright infringement related to Java, an open-source programming language, in the process of building Android, Google’s mobile operating system. It is well established that computer code written in a given language is protected by copyright. What has been less clear is the extent to which programming languages themselves enjoy the same protection, particularly when their source code is freely available (a status that makes them more analogous to spoken languages than to privately held code). Although Google won this particular battle, some technologists warn that the matter is far from settled—uncertainty that could have a chilling effect on technological innovation.