CHAPTER FOUR

FAKE SOCIALISM: CHINA

MAY 2017

It was obvious that China wasn’t a socialist country before our plane even landed in Beijing. Tall buildings, some of them skyscrapers, stretched for miles in multiple directions and didn’t have the uniform bland gray exteriors that typify socialist architecture. Heights, shapes, materials, and designs all varied. These initial impressions held as our modern taxi cab whisked us down the crowded but efficiently flowing ten-lane highway towards downtown. Not only were these modern buildings well maintained and varied, but they also bore telltale signs of capitalism—company names and logos.

We could have stayed in many great five-star hotels run by international companies in Beijing. But that would have been like staying in the Hotel Nacional in Havana and using that one experience to generalize about the other hotels. So, as in Cuba, we shot for decent hotels at reasonable prices. Only in China there was one major difference—our hotels didn’t totally suck.

The twenty-story Novotel Beijing Peace Hotel boasted four hundred rooms and contained Le Cabernet, a French restaurant, as well as another restaurant serving mixed international cuisine. The lobby bar was fully stocked, and I could order my standard double gin and tonics for around ten bucks each. The guest rooms were unremarkable, which is to say, nice. If you were just dropped into one of them, without knowing anything else, you’d probably guess you were in a Marriott or Sheraton hotel in the United States. In fact, if it wasn’t for the trinkets in the gift shops and all the Chinese people walking around, nothing in the hotel indicated we were in China at all.

That’s no accident. Novotel is part of the French multinational AccorHotels group. The Novotel chain has about four hundred hotels in sixty countries. It’s also privately owned, so it depends on customers’ purchases to stay in business. But we weren’t breaking the bank to buy luxury in a socialist country. Our reservation cost us $106 per night and we were about a kilometer from the city center, within easy walking distance of the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square. Well, it was easy for Bob at least. I was hobbling with a cane because I had semi-drunkenly broken my big toe while wearing flip-flops in Hawaii three weeks prior.

We had a few hours to kill before we met Dean Peng, who was going to help us find our way around China, so we decided to wander the neighborhood and get a beer. We were surrounded—engulfed is probably the better word—in capitalist commerce. Signs were everywhere, and they were signs we recognized: Rolex, Gap, McDonald’s, and Pizza Hut.

Just off the main street, Bob and I bobbed and weaved our way through crowded, narrow alleys where mom-and-pop small businesses sold silks, toys, and fried scorpion on a stick. We were relieved to find a bar with a couple of seats open. They were selling Tsingtao beer, oversized, and properly overpriced.

We were surrounded by free-market commerce in the capital of Communist China, which for nearly thirty years, under dictator Mao Zedong, had been one of the most repressive regimes in the world. As Chairman of China’s Communist Party, Mao ruled the “People’s Republic” from its founding in October 1949 until his death in 1976. His rule was near absolute. Party officials who dared to challenge him lost their jobs—or worse. Party members and peasants alike were expected to study his writings, including his “Little Red Book” of political and economic philosophy. As fake as the country’s socialism is now, the Communist Party still runs China, and children are still taught to revere “Chairman Mao,” almost certainly the biggest mass murderer in history.

Frank Dikötter, in his book Mao’s Great Famine, estimates that at least forty-five million people died unnecessarily in China between 1958 and 1962 alone. The great famine did not occur because of a drought or natural disaster; it occurred because of Mao’s economic plan for industrialization.

Mao’s inspiration was Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s 1957 promise that the Soviet Union would overtake the economic production of the United States within fifteen years. Mao responded that China would grow even more rapidly. His first goal was for China to overtake the economic output of Great Britain, and the result was his ambitious plan—called the Great Leap Forward—for the Communist government to industrialize China.

The Great Leap Forward became the great Chinese famine. But as Dikötter explains, referring to this tragedy as a mere famine “fails to capture the many ways in which people died under radical collectivization. The blithe use of the term ‘famine’ also lends support to the widespread view that these deaths were the unintended consequence of half-baked and poorly executed economic programmes.” In fact, “coercion, terror, and systematic violence were the foundations of the Great Leap Forward.”1 The Great Leap Forward could not even be justified under the usual socialist excuse of breaking a few eggs to create an omelet. In reality, it was a Great Leap Backward, killing tens of millions of people and destroying, rather than modernizing, China’s economy.

The government was already seizing small, family-run farms and moving the farmers into government-run “cooperatives” of about a thousand workers each. In 1958, Mao doubled down and merged the cooperatives into giant “people’s communes” that could incorporate as many as twenty thousand households. Party officials ran the communes, where nearly everything—land, tools, livestock—was collectivized. Millions upon millions of villagers were forcibly moved to make way for giant damming and other projects. Targets were set—and escalated—for communes to export not just food but also industrial products, such as steel. Backyard furnaces soon melted down pots, pans, farming tools, and anything else that was available to meet the quotas. To feed his cities and meet foreign export promises, Mao continued to demand more and more from the farmers, even as able-bodied farm workers were diverted to projects the planners cared more about, like building dams. The result was agricultural failure, famine (some of it implemented by commune leaders to motivate workers), and steel production (melted down scrap metal from backyard furnaces) that was economically useless.

Dikötter’s examination of Chinese Communist Party records shows that at least two and a half million people were summarily executed or tortured to death during the Great Leap Forward. Millions more starved because they were intentionally deprived of food as punishment, or because they were regarded as too old or weak to be productive, or because the people ladling out the slop in the chow line simply did not like them.

Our friend Li Schoolland remembered that during the later years of the Great Leap Forward, “We ate everything that didn’t kill us. I refused to eat rats. But my brother, he was a growing boy. He was so hungry. He ate it. We’d go to the pond and get the snails and the frogs.” Her family also ate “tree bark, tree leaves, grass, I knew all the grass that was edible.”2

Mao received many reports of starvation and suffering, but he and the Communist Party were unmoved. In late 1958 Mao’s foreign minister, Chen Yi, acknowledged that “casualties have indeed appeared among workers, but it is not enough to stop us in our tracks. This is a price we have to pay, it’s nothing to be afraid of. Who knows how many people have been sacrificed on the battlefields and in the prisons [for the revolutionary cause]? Now we have a few cases of illness and death: It’s nothing!”3 Eventually, however, the Communist Party had to relent in order to avoid complete catastrophe as the tens of millions of casualties piled up. By 1962, the Great Leap Forward had been abandoned, and some private farmland had been reintroduced. But it was a short-lived respite. In 1966, Mao and the Communist Party launched the “Cultural Revolution,” inflicting a new hell on the Chinese people.

The Cultural Revolution aimed to purge or reeducate the counterrevolutionary bourgeois elements of Chinese society. It also served to reassert Mao’s power after the failure of the Great Leap Forward. Senior officials, including the future reformer Deng Xiaoping, were purged from leadership in the Communist Party. Historical sites and relics that honored things from China’s pre-Communist past were destroyed. Roughly seventeen million young people were sent to the rural countryside for class reeducation.4 Other young people formed the Red Guard and attacked anyone insufficiently supportive of Maoism. The death toll of the Cultural Revolution is estimated at somewhere between half a million and two million people.5

All told, in less than thirty years, through the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, and other atrocities, Mao’s Communist government killed more of its own people than any other government in history—possibly as many as eighty million.6 The peasants who escaped death found themselves poorer than their ancestors. In 1978, two-thirds of Chinese peasants had incomes lower than they had in the 1950s, one-third had incomes lower than in the 1930s, and the average Chinese person was only consuming two-thirds as many calories as the average person in a developed country.7

But none of this suffering was obvious from where we stood now in Tiananmen Square. Rather than starving peasants, we were surrounded by Chinese tourists sporting digital cameras, cell phones, and shopping bags. The Communist Party continues to govern China, but it has allowed free-market reforms that have delivered prosperity.

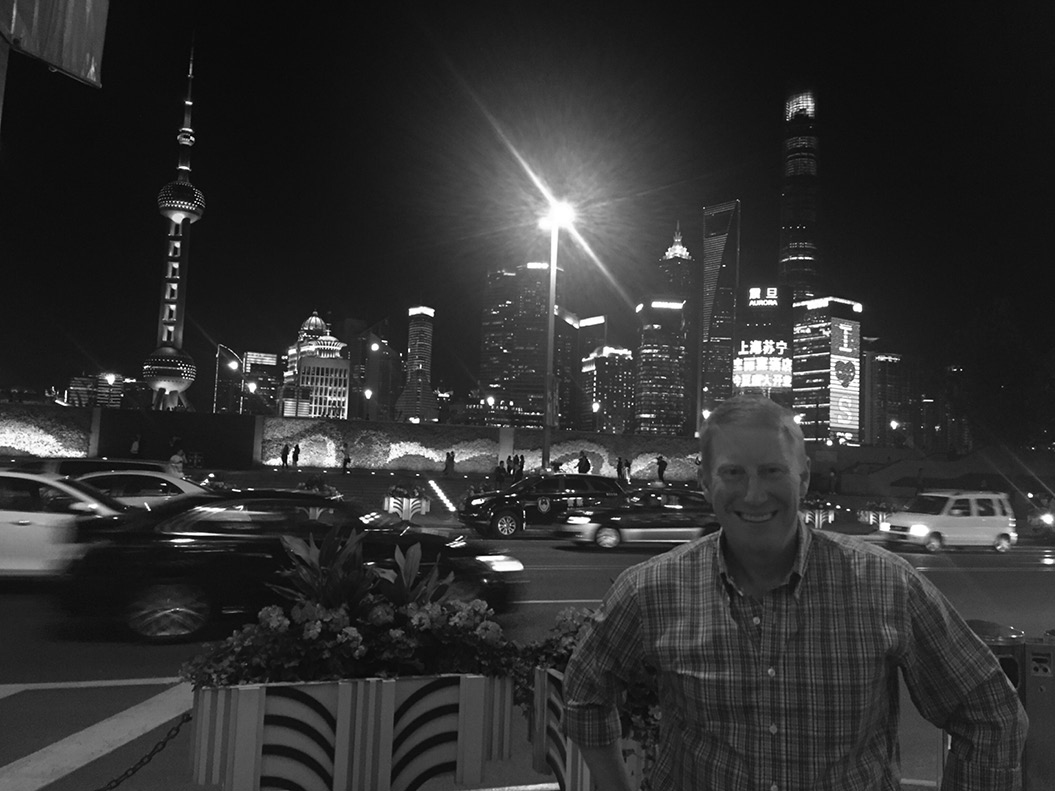

If this was obvious in Beijing, it was even more obvious in our next stop—Shanghai. The Shanghai Tower—2,073 feet and 127 stories tall—is the second-tallest building in the world. Its observation deck, complete with beer-serving café, afforded us a 360-degree bird’s-eye view of countless high-rises along both banks of the Huangpu River, a tributary of the Yangtze. The river itself was chock-full of barges serving the world’s busiest container port. It’s hard to decide what counts as a high-rise in Shanghai. There were far more thirty-story buildings than I could count. Even limiting myself to the forty- or fifty-story buildings would have been dizzying, especially after I’d consumed a few of the café’s beers. Nearly next door to the Shanghai Tower, the nine-year-old Shanghai World Financial Center stands at 101 stories and 1,614 feet. Not far beyond that is Shanghai’s iconic 1,535-foot-tall Oriental Pearl Tower. Completed in 1994, the Pearl is the oldest of Shanghai’s mega skyscrapers.

In fact, nearly everything on the east side of the river was new. As recently as 1990, this area, known as Pudong, had been a slum. But in less than a generation those slums were replaced by mega skyscrapers, shopping outlets, a financial district, and high-end hotels. In fact, I wish we had stayed in one of those hotels. Instead, after SMU’s travel agency screwed up our reservations, Bob booked us last-minute at the Hotel Ibis, another AccorHotels property, across the river in old Shanghai’s historical center. And it sucked. Not Cuba suck. More like wet-dog smell, shitty AC, no bar or mini bar, Motel 6, American-variety suck. Oh well, capitalism usually provides, but even capitalism can’t always overcome problems stemming from university bureaucracies.

Ben takes a break from drinking with Bob’s SMU students in definitely not-socialist Shanghai. The Pudong district across the river behind him was a slum before 1993, when it became a special economic zone with greater economic freedoms and immediately began transforming into the rich, developed city you see here.

China’s economic development since 1978 is one of the greatest successes of its kind in human history. In sheer numbers, more people have escaped from extreme poverty, defined as earning less than two dollars a day, than at any other time or place. In 2011, 750 million fewer Chinese lived in absolute poverty than in 1981. Their living standards improved dramatically because the Chinese Communist Party adopted free-market policies.

The reforms started slowly, with collectivized farms contracting land to farmers who could sell their surplus (after they met their quotas) on private markets. The government recognized that farmers free to make profits were more productive. Instead of following their Communist ideology, government bureaucrats finally accepted the facts and allowed increasing degrees of private property.

Private enterprise was, in part, an unexpected by-product of the seventeen million Chinese young people who returned to the cities after their forced rural reeducation at the end of the Cultural Revolution. They needed jobs that inefficient, state-owned industries couldn’t provide—so self-employment became legal, as did small private businesses. By law, such businesses could only employ up to seven people, but in practice, by 1985, the average private company in China employed thirty people.8

Under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the Communist Party made effective economic development, rather than ideological purity, the focus of government policy, claiming, “It doesn’t matter whether the cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice.” No surprise to us, the more capitalist the cat, the more effective it was at catching mice. Deng defined his policy as “market socialism with Chinese characteristics,” which really was hardly socialism at all.

Bob had tracked China’s development with his economic freedom index. In 1980, the first year for which he had reliable data, China scored only 3.64 out of 10, placing it at the bottom 10 percent of countries in the world. By 1990, China’s economic freedom score had jumped 75 percent to 6.40. In 1988, the Chinese constitution was amended to officially recognize private property and private business. Before then, the Communist state had been China’s only official employer, with small exceptions. By 1998, the state employed about 60 percent of the working population, and in 2010 it employed only about 19 percent.9 China had transitioned from socialism to a form of crony capitalism.

Bob recited all these statistics at a fancy bar, holding court to a group of his SMU MBA students we had literally just chanced upon. They listened politely and then bought us a round of shots, hoping we’d take the hint and leave. We did, stumbling our way along the Bund, a riverfront walkway through the old colonial concessions to the British, American, and French governments that had opened up Shanghai as an international trade port in the nineteenth century. Across the river, the Pudong skyline glowed a brilliant blue, pink, red, purple, white, and gold. I gestured drunkenly in its direction and told Bob, “You know, your index misses a lot of that.”

That’s because Bob’s index measures policies mostly at the national level, so it can underestimate the contribution of a place like Pudong, which is a special economic zone (SEZ) with certain commercial privileges. Shanghai and thirteen other cities became SEZs in 1984, and Pudong became one in 1993. Special economic zones pay no customs duties on internationally traded goods, are exempt from income taxes, and have a host of other pro-capitalism rules that the rest of China hasn’t yet adopted.

Pudong is also included in the Lujiazui Finance and Trade Zone, which grants additional freedoms to foreign financial institutions and banks. This is a major advantage, because the Chinese government monopolizes the finance industry in most of the country. Pudong also includes the Waigaoqiao Free Trade Zone, which, at about four square miles, is the largest free trade zone in mainland China.

The economic freedom granted in SEZs has fueled much of China’s growth. Today, in Pudong, annual incomes average more than $20,000. Yet, according to the World Bank, throughout the rest of the country more than a third of Chinese people still live on less than $5.50 a day. Meanwhile, the population of Shanghai has exploded from eleven million people in 1980 to more than twenty-four million. Its population density is nearly three times that of Beijing, which has also seen its population surge.

In fact, the massive movement of people from low-productivity rural areas to cities with private industry has spurred China’s development. In the years since reform began, more than 260 million migrants moved from rural areas to urban centers in China, helping to transform China from a rural, socialist hellhole to an increasingly urbanized, mostly capitalist country. But on our trip we were reminded that, politically at least, China is still a Communist police state.

In Beijing, Bob and I had been invited by a young Chinese scholar, Ma Junjie, to speak at a conference about Austrian economics and the author Ayn Rand. The conference was organized by Unirule—an influential, private, free-market, Chinese think tank—and our friend, Yaron Brook, who runs the Ayn Rand Institute.

Yaron is a gray-haired former-finance-professor-turned-philosopher who travels the world evangelizing for the ideas of Ayn Rand. In attendance were about thirty Chinese academics, graduate students, think-tank scholars, and journalists. Discussing the ideas of novelist Ayn Rand, one of the most ardent anti-Communists of the twentieth century, while in the heart of Beijing was pretty damned surreal for us, but we did our best, participating on a panel discussion about Austrian economics and Ayn Rand’s philosophy of objectivism.

A couple of conference attendees drove us to dinner afterwards. As it happened, our route took us by Mao’s mausoleum. The fellow in the passenger seat turned around to us, nodded toward the massive complex, and said, “Maybe in twenty-five years we can get rid of him.” The driver laughed and shouted, “No! Ten years!” In China, this is risky talk.

The next day, after we had departed for Shanghai, Li Schoolland sent us an email: “I hope you didn’t go to the Unirule event yesterday!”

Using our VPN-equipped cell phones, we circumvented Chinese government censorship and accessed the internet. The South China Morning Post reported, “A two-day academic seminar at China’s largest non-official think tank was called off on Saturday because doors and lifts at its office building were locked and disabled amid upgraded security for Beijing’s two-day belt and road forum that begins on Sunday.”10

Li’s second email provided more details. “Yesterday before the meeting, the government blockaded the building where Unirule’s office is located and hired some thugs to beat up people who tried to enter. So the event had to cancel. Very bad situation and dangerous.” We also discovered that Unirule’s founder, eighty-eight-year-old Mao Yushi, who has received the prestigious international Milton Friedman Prize for Advancing Liberty, had police officers arrive at his house that morning to prevent him from leaving for the conference.

Bob nerds out to Ayn Rand at the Unirule Institute meeting in Beijing. The meeting would be shut down by the government the very next morning.

Since our departure, Communist Party leader Xi Jinping has continued his crackdown on dissent, and on Unirule. The government shut down Unirule’s websites and social media accounts and forced the institute to vacate its downtown offices that we had visited. Unirule moved to western Beijing, put up a website accessible only to those with VPN software, and was continually harassed.11 In July 2018, the building landlord evicted Unirule, though the institute had always paid its bills. The institute’s executive director, Sheng Hong, explained, “The leasing company is out to make money, and there’s no reason that they’d make trouble on their own. That would be illogical.”12 Instead, Sheng explained, “It must be the pressure from the government. The authorities do not want [to tolerate] a different voice, but they do not want to brazenly shut us down either, because that would make it look too terrible.” Instead, “They obviously want to try to turn it into a civil dispute, but people are not idiots and everyone can tell what’s the real matter here.”13

When Communist China was governed by socialist ideologues it was an impoverished, totalitarian police state that killed tens of millions of its own people. Now that Communist China practices crony capitalism, it is a prosperous and much more restrained police state. That sucks, but believe us—that’s still progress.