People in poorer parts of the world today may easily be the first in their family to have graduated from a secondary school. At the same time many children still never attend a primary school, let alone persevere through what is considered in rich countries to be a basic education. And university education is rare. In contrast, the affluent world is characterised by long-standing and ever-improving compulsory primary and secondary education for all children, with rates of university access rising almost continuously. Despite this, many young people are not presented as well educated in most affluent nations, but as failing to reach official targets. This chapter brings together evidence which shows how particular groups are increasingly seen as ‘not fit’ for advanced education, as being limited in their abilities, as requiring less of an education than the supposedly more gifted and talented.

The amassing of riches in affluent countries, the riches which allowed so much to be spent on education, has not resulted in an increased sense of satisfaction in terms of how young people are being taught and are learning. Instead, it has allowed an education system to be created which now expresses ever-increasing anxiety over how pupils perform, in which it has become common to divide up groups of children by so-called ability at younger and younger ages to try to coach them to reach ‘appropriate’ targets. This has a cumulative effect, with adolescents becoming more anxious as a result. Despite the abandonment of the former grammar school system in Britain, children are still being divided among and within schools. This is also evident in the US, but in Britain it is more covert. Parents have been moving home in order to get their children into their chosen state school, they may pretend to be religious to gain access to faith schools, and slightly more of them were paying for private education by 2007 than had done so before. As more resources are concentrated on a minority the (perceived) capabilities of the majority are implicitly criticised.

In this chapter evidence is brought together to show how myths of inherent difference have been sustained and reinforced by placing a minority on pedestals for others to look up to. Such attitudes vary in degree among affluent nations but accelerated in intensity during the 1950s (to be later temporarily reversed in the 1960s and 1970s). In the 1950s, in countries like Britain, the state enthusiastically sponsored the division of children into types, with the amounts spent per head on grammar school children being much higher than on those at the alternative secondary moderns. Such segregationist policies are still pursued with most determination in the more unequal rich countries. More equitable countries, and the more equitable parts of unequal countries (such as Scotland and Wales in Britain), have pushed back most against this tide of elitism since it rose so high in the 1950s.

Elitism in education can be considered a new injustice because, until very recently, too few children even in affluent countries were educated for any length of time. All are now at risk of being labelled as ‘inadequate’ despite the fact that the resources are there to teach them, of being told that they are simply not up to learning what the world now demands of them. Those who are elevated also suffer.

All will fail at some hurdle in an education system where examination has become so dominant. To give an example I am very familiar with, in universities, professors, using elitist rhetoric, try to tell others that the world is complicated and only they are able to understand or make sense of it; they will let you see a glimpse, they say, if you listen, but you cannot expect to understand; it takes years of immersion in academia, they claim; complex words and notions are essential, and they see understandable accounts as ‘one-dimensional’.1

Occasionally there is no alternative to a complex account of how part of the world appears to work, but often a complex account is simply a muddled account. Professors often say that an aspect of the world is too complex for them to describe clearly because they themselves cannot describe it in a clear way, not because it cannot be described clearly. Suggesting such widespread complexity justifies the existence of academia because elitism forces those it puts on pedestals to pretend to greatness, but if you talk to academics it thankfully becomes clear that most are, to some extent, aware of this pretence. They are aware, like the Wizard of Oz, of how humdrum they really are.

People are remarkably equal in ability. However, if you spend some time looking you can find a few people, especially in politics, celebrity (now a field of work) or business, who appear to truly believe they are especially gifted, that they are a gift to others who should be grateful for their talents and who should reward them appropriately. These people are just as much victims of elitism as those who are told they are, in effect, congenitally stupid, fit for little but taking orders and performing menial toil despite having been required to spend over a decade in school. Under elitism education is less about learning and more about dividing people, sorting out the supposed wheat from the chaff and conferring high status upon a minority.

The old evil of ignorance harmed poorer people in particular because they could not read and write and were thus easily controlled, finding it harder to organise and to understand what was going on (especially before radio broadcasts). What differentiates most clearly the new social injustice of elitism from the old evil of ignorance is that elitism damages people from the very top to the very bottom of society, rather than just being an affliction of the poor. Those at the top suffer because the less affluent and the poor have their abilities denounced to such an extent that fewer people end up becoming qualified in ways that would also improve the lives of the rich. For example, if more people were taught well enough to become medical researchers then conditions that the rich may die of could be made less painful, or perhaps even cured, prolonging their lives. If more are taught badly at school, because it is labourers and servants that the rich think they lack, then cures for illnesses may not be discovered as quickly.

The British education system has been described as ‘learning to labour’ for good reason. But it is, however, the poorest who are still most clearly damaged by elitism, by the shame that comes with being told that their ability borders on illiteracy, that there is something wrong with them because of who they are, that they are poor because they have inadequate ability to be anything else.

Although nobody officially labels a seventh of children as ‘delinquent’, they might just as well because that is the stigmatising effect of the modern labels that are applied to children seen as the ‘least able’. A century ago delinquency was an obsession and thought to lead to criminality; education was the proffered antidote. However, it was not lack of education that caused criminality in the young, at least not a lack of the mind-numbing rote-and-rule learning that so commonly used to be offered as education; it was most often necessity. Today it is money for drugs rather than food, as the nature of the need has changed, but old labels such as ‘delinquent’ are retained in the popular press, and a new form of what can still best be described as ‘delinquency’ has arisen.

Increased educational provision that has been increasingly unequally distributed has led to the rise of this new elitism. Where once there had been the castle on the hill and the poor at the gates, the castle grounds were then subdivided into sections, places up and down the hill, neatly ordered by some supposed merit. And today an even neater ordering of people has been achieved – to demarcate social position and occupation all now have numbers and scores, exam passes, credit ratings, postcodes and loyalty cards, rather than simply titles and surnames.

Scoring all individuals in affluent societies is a very recent affair. Giving all children numbers and grades throughout their schooling and yet more grades afterwards (at university or college) was simply not affordable before the Second World War in even the most affluent of countries. It was a luxury confined to the old grammar schools and universities. At that time, most children would simply be given a certificate when they left school to say that they had attended. This system changed when compulsory secondary education for all swept the affluent world following the war, although with the belief that all could be educated came the caveat that most of those who believed this did not see all the children that they were about to allow through to secondary school as equal in potential ability.

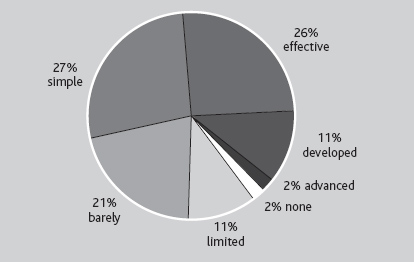

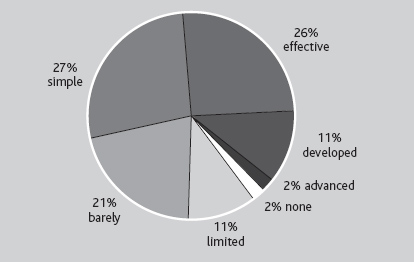

Some of the best evidence of policy makers seeing different groups of children as so very different comes from the work of educational economists. Half a century ago the rich countries created a club, the OECD, effectively a rich country club which is now dominated by economists. It was partly the rise in power of economists belonging to clubs like the OECD which resulted in elitism growing, and through which the beliefs of elitism were spread. That club published the figures used to draw Figure 1 (below), figures that suggest that one in seven children growing up in one particular rich country today (the Netherlands) have either no or very limited knowledge.2

We used to see the fate of children as being governed by chance, with perhaps even the day of their birth influencing their future life. Rewriting the old rhyme, the OECD would say of children today (in the Netherlands) that they can be divided into seven differently sized groups by their supposed talents and future prospects:

The educational ode of the OECD*

Monday’s child has limited knowledge,

Tuesday’s child won’t go to college,

Wednesday’s child is a simple soul,

Thursday’s child has far to go,

Friday’s child can reflect on her actions,

Saturday’s child integrates explanations,

But the child that is born on the Sabbath day

Has critical insight and so gets the most say.

The OECD economists and writers do not put it as crudely as this, however. It is through their publications (from which come the labels that follow)3 that they say in effect that there is now a place where a seventh of children are labelled as failures by the time they reach their 15th birthday.

Using OECD data, if we divide children into seven unequally sized groups by the days of the week and start with those most lowly ordered, then the first group are Monday’s children (from Figure 3.1, 11%+2%=13%). They are those who have been tested and found to have, at most, only ‘very limited knowledge’. Tuesday’s children (21%) are deemed to have acquired only ‘barely adequate knowledge’ to get by in life. Wednesday’s and Thursday’s children (27%) are labelled as being just up to coping with ‘simple concepts’. Friday’s and Saturday’s children (26%) are assessed as having what is called ‘effective knowledge’, enough to be able to reflect on their actions using scientific evidence, perhaps even to bring some of that evidence together, to integrate it. The remaining children (11%+2%=13%), one in every seven again, are found by the testers to be able to do more than that, to be able to use well-‘developed inquiry abilities’, to link knowledge appropriately and to bring ‘critical insights’ to situations. But although these children may appear to be thinking along the lines that those setting the tests think is appropriate, even they are not all destined for greatness. According to the testers they will usually not become truly ‘advanced thinkers’. It is just one in seven of the Sabbath children (100%÷7÷7=2%) who is found to be truly special. Only this child, the seventh born of the seventh born, will (it is decreed) clearly and consistently demonstrate ‘advanced scientific thinking and reasoning’, will be able to demonstrate a willingness to use scientific understanding ‘in support of recommendations and decisions that centre on personal, socioeconomic, or global situations’.4 This child and the few like them, it is implied, are destined to be our future leaders.

Figure 1 shows the proportions of children in the Netherlands assigned to each ability label from ‘none’ clockwise round to ‘advanced’. The Netherlands is a place you might not have realised had brought up over 60% of its children to have only a simple, barely adequate, limited education, or even no effective education at all (according to OECD statistics).

Notes: ‘None’ implies possessing no knowledge as far as can be measured. ‘Limited’ implies possessing very limited knowledge. ‘Barely’ stands for barely possessing adequate knowledge in the minds of the assessors. ‘Simple’ means understanding only simple concepts. ‘Effective’ is a little less damning. ‘Developed’ is better again; but only ‘advanced’ pupils are found to be capable, it is said, of the kind of thinking that might include ‘critical insight’.

Source: OECD (2007) The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), OECD’s latest PISA study of learning skills among 15-year-olds, Paris: OECD, derived from figures in table 1, p 20

The OECD, an organisation of economists (note not teachers), now tells countries how well or badly educated their children are. And it is according to these economists that the Netherlands is the country which best approximates to the 1:1:2:2:1 distribution of children having what is called limited, barely adequate, simple, effective and developed knowledge, by having reached the OECD’s international testing levels 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 respectively. This is not how children in the Netherlands actually are, nor how they appear to any group but the OECD;it is not how the majority of their parents think of them; it is not even how their teachers, school inspectors or government rank them;but it is how the children of the Netherlands, and all other children in the richer countries of the world, have slowly come to be seen by thosall othere who carry out these large-scale official international comparisons. Large-scale international comparisons can be great studies, but should not be used to propagate elitist beliefs.

Given this damning description of their children it may surprise you to learn that the Netherlands fare particularly well compared with other countries. Only half a dozen countries out of over 50 surveyed did significantly better when last compared (in 2006). More children in the UK were awarded the more damning levels of 1, 2 and 3 - ‘limited’, ‘barely adequate’ and ‘simple’. In the US both Monday’s and Tuesday’s children were found to be limited, and only half of Sunday’s children were ‘developed’ – just half the Netherlands’ proportion.

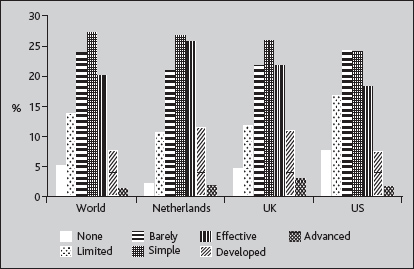

Do the best of the richest countries in the world really only educate just under a seventh (13%) of their children to a good level, and just a seventh of those (2%) to a level where they show real promise? Are just 2% of children able, as the OECD definition puts it, to ‘use scientific knowledge and develop arguments in support of recommendations and decisions that centre on personal, socioeconomic, or global situations’? In Finland and New Zealand this ‘genius strand’ is apparently 4%, in the UK and Australia 3%, in Germany and the Netherlands 2%, in the US and Sweden 1%, and in Portugal and Italy it is nearer to 0%. These are children who, according to the educational economists, show real promise. They are the children who have been trained in techniques so as to be able to answer exam questions in the ways the examiners who operate under what are called ‘orthodox economic beliefs’ would most like them to be answered. The proportions are so low because the international tests are set so that the results are distributed around a ‘bell curve’. This is a bell curve with smoothly tapering tails, cut off (internationally and intentionally) so that 1.3% are labelled genii and 5.2% as know-nothings (see Figure 2 on page 47 below).

Economists use the results of their international comparative exercises for the purpose of making claims, such as ‘… having a larger number of schools that compete for students was associated with better results’.4 Many of the people who work for organisations such as the OECD feel they have a duty to suggest that competition between countries, schools and pupils is good, and to encourage it as much as they can.

According to this way of thinking, science education, which is usually extended to include technology, engineering, maths and (quietly) economics,5 is the most important education of all. Supporting such science education, its promotion and grading in these ways, is seen as working in support of recommendations and decisions that centre on best improving personal, socioeconomic and global situations to engineer the best of all possible worlds. This imagined world is a utopia with all benefiting from increased competition, from being labelled by their apparent competencies. This is a world where it is imagined that the good of the many is most enhanced by promoting the ability of the few.

Although the OECD tables, and almost all other similar performance tables, are presented explicitly as being helpful to those towards the bottom of their leagues, as being produced to help pull up those at the bottom, this is rarely what they achieve. Educational gaps have not narrowed in most places where such tables have been drawn up. This is partly because they suggest how little hope most have of ever being really competent; ‘leave competency to the top 2%’ is the implicit message, for, unless you are in the top seventh, you cannot hope to have a chance of succeeding, where success means to lead. Even when standards improve and most level 1 children are replaced by level 2, level 2 by 3, and so on, the knowledge which is judged to matter will also have changed and become ever more complex. If we accept this thinking, the bell curves will be forever with us.

This bell curve thinking (Figure 2, page 47) suggests that right across the rich world children are distributed by skill in such a way that there is a tiny tail of truly gifted young people, and a bulk of know-nothings, or limited, or barely able or just simple young people. It is no great jump from this to thinking that, given the narrative of a shortage of truly gifted children, then as young working adults those children will be able to name their price and will respond well to high financial reward. In contrast, the less able are so numerous they will need to be cajoled to work. These masses of children, the large majority, will not be up to doing any interesting work, and to get people to do uninteresting work requires the threat of suffering. This argument quickly turns then to suggest that they will respond best to financial rewards sufficiently low as to force them to labour. It is best to keep them occupied through hours of drudgery, it has been argued, admittedly more vocally in the past than now.

But what of those in between, of Friday’s and Saturday’s children, with effective but not well-developed knowledge – what is to be done with them? Offer them a little more, an average wage for work, a wage that is not so demeaning, and then expect them to stand between the rest of weekday children and those of the Sabbath, a place half way up the hill. Give them enough money for a rest now and again, one big holiday a year, money to run a couple of cars, enough to be able to struggle to help their children get a mortgage (the middle-class aspiration to be allowed to have a great debt).

But surely (you might think) there are some groups of children who are simply born less able than others, or made so by the way they have been brought up in their earlier years? Most commonly these are infants starved of oxygen in the womb or during birth, denied basic nutrients during infancy. Such privations occur early on in the lives of many of the world’s poorest children. But this physical damage, mostly preventable and due in most cases to absolute poverty, now rarely occurs in North America, affluent East Asia or Western Europe. When serious neglect does occur the results are so obvious in the outcomes for the children that they clearly stand out. The only recent European group of children treated systematically in this way were babies given almost no human contact, semi-starved and confined to their cots in Romanian orphanages. They have been found to have had their fate damaged irreparably. Medical scanning discovered that a part of their brain did not fully develop during the first few years of their lives, and their story is now often told as potential evidence of how vital human nurturing is to development.6

Two generations earlier than the Romanian orphanages, from Germany and Austria, come some of the most telling stories of the effects that different kinds of nurturing can have on later behaviour. There are worse things you can do to children than neglect them. It is worth remembering the wartime carnage that resulted in the creation of the institutions for international solidarity. We easily now forget where the idea that there should be economic cooperation in place of competition came from. The most studied single small groups of individuals were those who came to run Germany from the mid-1930s through to the end of the Second World War. To understand why the word ‘co-operation’ remains in the title of the OECD, it is worth looking back at the Nazis (and their elitist and eugenicist beliefs) when we consider what we have created in the long period of reconstruction after that carnage.

The childhood upbringings of the men who later became leading members of the Nazi party have been reconstructed and studied as carefully as possible. Those studies found that as children these men were usually brought up with much discipline, very strictly and often with cruelty. They were not born Nazis – the national social environment and their home environment both had to be particularly warped to make them so. Warped in the other direction, it has been found, were the typical home environments of those equally rare German and Austrian children who grew up at the same time and in the same places but went on to rescue Jewish people from the Nazi regime. Their national social environment was identical. Their home environment also tended to revolve around high standards, but standards about caring for others; the home was rarely strict and as far as we know, never cruel. It was ‘… virtually the exact opposite of the upbringing of the leading Nazis’.7 Further studies have found that many of the rescuers discovered that they had no choice but to help, it having been instilled in them from an early age. ‘They would not be able to go on living if they failed to defend the lives of others.’8

Across Europe in the 1940s there were too few rescuers, and most Jews targeted for persecution were killed. The fact that people in mainland Europe9 were largely complicit in the killing, and are still reluctant to accept this truth, is claimed as part of the reason for current silences about ‘race’; it remains ‘… an embarrassment’.10 However, out of that war came a desire to cooperate better internationally.

The OECD, later so widely criticised as a rich country club, was not set up to preserve privilege, reinforce stereotypes and encourage hierarchy. Originally called the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC), it was established to administer US and Canadian aid to war-ravaged Europe. That thinking changed in the 1950s, and it was renamed the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1961. Its remit gradually gravitated towards concentrating on what was called improving efficiency, honing market systems, expanding free trade and encouraging competition (much more than cooperation). By 2008 the OECD was being described in at least one textbook as a ‘… crude, lumbering think-tank of the most wealthy nations, bulldozing over human dignity without pause for thought. Its tracks, crushed into the barren dereliction left behind, spell “global free market”’.11 The organisation describes its future a little differently, as ‘… looking ahead to a post-industrial age in which it aims to tightly weave OECD economies into a yet more prosperous and increasingly knowledge-based world economy’.12

The knowledge base that the OECD refers to is a particular kind of knowledge that comes from a particular way of valuing people, of seeing the world, a way that came to dominate the thinking of those appointed to high office in the rich world by the start of the 21st century. From the late 1970s onwards, if you did not think in this particular way you would be quite unlikely to be appointed to work for bodies such as the OECD, or to rise high within any government in an unequal affluent nation, even less likely to do well in business. This way of thinking sees money as bringing dignity, sees children as being of greatly varying abilities and sees its own educational testers as knowing all the correct answers to its battery of questions, which include questions for which there is clearly no international agreement over the correct answers.13 It is not hard to devise a set of questions and a marking scheme that results in those you test appearing to be distributed along a bell curve. But to do this, you have to construct the world as being like this in your mind. It is not revealed as such by observation.

What observation reveals is that ever since we have been trying to measure ‘intelligence’ we have found it has been rising dramatically.14 This is true across almost all countries in which we have tried to measure it.15 This means that the average child in 1900 measured by today’s standards would appear to be an imbecile, ‘mentally retarded’ (the term used in the past), a ‘virtual automaton’.16 When we measure our intelligence in this way it appears so much greater than our parents’ that you would think they would have marvelled at how clever their children were (but they didn’t).17 What this actually means is that in affluent countries over the course of the last century we have become better educated in the kind of scientific thinking which scores highly in intelligence tests. More of us have been brought up in small households and therefore given more attention. We have been better fed and clothed. Parenting did improve in general, but we were also expected to compete more and perform better at those particular tasks measured by intelligence tests.

If our grandparents had been the ‘imbeciles’ their test results would (by today’s standards) now suggest, they would not have been able to cooperate to survive. Although today’s young people have been trained to think in abstract ways and to solve theoretical problems on the spot (it would be surprising if they could not, given how many now go on to university), there are other things they cannot do which their grandparents could. Their grandparents could get by easily without air conditioning and central heating, and many grew their own food, while their grandchildren often do not know how to mend things and do more practical work. Our grandparents might not have had as much ‘critical acumen’ on average, but they were not exposed to the kind of mental pollution that dulls acumen such as television advertising, with all the misleading messages it imparts. Observation tells us that intelligence merely reflects environment and is only one small part of what it means to be clever. Despite this, ‘critical acumen’, the one small highly malleable part of thinking that has become so much more common over the course of recent generations, has mistakenly come to be seen both as all important and as unequally distributed within just one generation.

A new way of thinking, a theory, was needed to describe a world in which just a few would be destined to have minds capable of leading the rest and in which all could be ordered along a scale of ability. That new way of thinking has come to be called ‘IQism’. This is a belief in the validity of the intelligence quotient (IQ), and in the related testing of children resulting in their being described as having ability strung along a series of remarkably similar-looking bell curves, as shown in Figure 2. The merits of thinking of intelligence as having a quotient came out of wartime thinking and were pushed forward fastest in the 1950s when many young children and teenagers were put through intelligence tests. In Britain almost all 11-year-olds were subjected to testing (the ‘11 plus’), which included similar ‘intelligence’ tests, to determine which kind of secondary school they would be sent to. Although such sorting of children is no longer so blatantly undertaken, the beliefs that led to this discrimination against the majority are now the mainstream beliefs of those who currently make recommendations over how affluent economies are run. And, just as we no longer divide children so crudely by subjecting them to just one test, the educational economists are now careful not to draw graphs of the figures they publish – this would present a miserable picture of the futures of those for whom the bell curves toll. There are no histograms of these results in the OECD report in which the data used here are presented.

If children had a particular upper limit to their intellectual abilities, an IQ, and that limit was distributed along a bell curve, then it would be fair to ascribe each to a particular level, to suggest that perhaps in some countries children were not quite performing at the levels they could be. But is it really true that in no country do more than 4% of children show signs of being truly able?18

Almost identical curves could be drawn for different countries if human ability were greatly limited, such as those curves shown in Figure 2. This figure is drawn from the key findings of the 2007 OECD report, which includes six graphs. None of those graphs show a single bell curve. Figure 2 reveals how the OECD economists think ability is distributed among its member countries, and in three particular places. It is possible that the OECD economists were themselves reluctant to draw the graph because they knew it would rightly arouse suspicion. However, it is far from easy to guess at motive. What it is possible, if extremely tedious, to do is to read the technical manual and find hidden, after 144 pages of equations and procedures, the fact that those releasing this data, when calibrating the results (adjusting the scores before release), ‘… assumed that students have been sampled from a multivariate normal distribution’.19 Given this assumption, almost no matter how the students had ‘performed’, the curves in Figure 2 would have been bell shaped. The data were made to fit the curve.

Source: Data given in OECD (2007) The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), OECD’s latest PISA study of learning skills among 15-year-olds, Paris: OECD, derived from figures in table 1, p 20

There is very little room under a bell curve to be at the top. Bell-curved distributions suggest that, at best, if most were destined to have their abilities lifted the vast majority (even if improved) would remain ‘limited’, or barely ‘adequate’, or just able to understand ‘simple things’. The implication of ability being strung out like this is that even following educational gain, the many would always have to be governed by the few, the elite, ‘the advanced’. If this testing is producing scores with any kind of validity concerning underlying ability, then only a very few children will ever grow up to understand what is going on. If this is not the case, if there is not just a tiny minority of truly able children, then to describe children in this way, and to offer prescriptions given such a description (and the subsequent outcomes), is deeply unjust.

Those people who believe in IQ have been thinking and writing about it for less than a century. It is not an old idea. The concept was first proposed in 1912 with the German name Intelligenz-Quotient, derived from testing that occurred just a few years earlier in 1905 in France, but testing that did not, initially, assume a limit. The concept of assuming a limit to children’s intellectual potential was subsequently developed by those with a taste for testing. The assumption was that intellectual ability was limited physically, like height. Different children would grow to different heights, which tended to be related to their parents’ heights, but also to the wider social environment which influenced their nutrition, their exercise and their well-being.

The idea that intellectual ability is distributed like height was proposed within just a few years of the bell curve itself first being described mathematically. It is now easy to see how it could have been imagined, why the idea of IQ and the concept of its hereditability came to flourish. Most people who were told of the idea were also told that their IQ was high. People who propagated the idea thought that their IQs were even higher. People enjoy flattery – it makes us feel safe and valued. But, tragically, in the round, the concept of IQ made no individuals actually safer or more valued for who they really were. Great evils of genocide were carried out under IQism (and related beliefs). But as those evils become memories, as the stories of early elitism are forgotten, as the old-fashioned social evil of illiteracy is largely overcome in affluent nations, IQism is growing again as an ideological source for injustice.

Those recognised as making progress in the study of education suggest that thinking is as much like height as singing is like weight. You can think on your own, but you are best learning to think with others. Education does not unfold from within but is almost all ‘… induction from without’.20 There are no real ‘know-nothings’; they could not function. Children are not limited, or barely able, or simple. We are all occasionally stupid, especially when we have not had enough sleep, or feel anxious and ‘don’t think’.

If you use singing as a metaphor for education, we are similarly all capable of singing or not singing, singing better or worse. What is seen as good singing is remarkably culturally specific, varying greatly by time and place. Work hard at your singing in a particular time and place, and people will say you sing well if you sing as you are supposed to. It is possible to rank singing, to grade it and to believe that some singing is truly awful and other singing exquisite, but the truth of that is as much in the culture and ears of the listener as it is in the vocal cords of the performer. Someone has almost certainly been silly enough to propose that human beings have singing limits which are distributed along a bell-shaped curve.21 After all is said, despite the fact that we are all capable of being stupid, the bell-curve-of-singing idea did not catch on. We are not as vain about how good we are at yodelling in the shower as we are about being told we are especially clever. We can all sing, we can all be stupid, we can all be clever, we can learn without limits.

It is only recently that it has been possible to make the claim that almost all children in rich countries are capable of learning without limits. The same was not true of many of their parents and of even fewer of their grandparents. And the same is not true of almost a tenth of children worldwide, some 200 million five-year-olds. These children are the real ‘failures’, failing to develop all their basic cognitive functions due to iodine or iron deficiency, or malnutrition in general leading to stunting of the brain as well as the body, and/or having received inadequate stimulation from others when very young.22 Children need to be well fed and cared for both to learn to think well and to be physically able enough to think well, just as they do to be able to sing well. But well fed and loved, there is no subsequent physical limiting factor other than what is around them. If you grow up in a community where people do not sing, it is unlikely that you will sing. If you grow up where singing is the norm, you are likely to partake.

Much of what we do now our recent ancestors never did. They did not drive cars, work on computers; few practised the violin, and hardly any played football, so why do we talk of a violinist or a footballer having innate talent? Human beings did not slowly evolve in a world where those whose keyboard skills were not quite up to scratch were a little less successful at mating than the more nimble fingered. We learn all these things; we were not born to them, but we are born elastic enough to learn. How we subsequently perform in tests almost entirely reflects the environment we grew up in, not differences in the structures of our brains.23 However, there remains a widespread misconception that ability, and especially particular abilities, are innate, that they unfold from within, and are distributed very unevenly, with just a few being truly talented, having been given a gift and having the potential to unfold that gift within them, hence the term ‘gifted’.

The misconception of the existence of the gifted grew out of beliefs that talents were bestowed by the gods, who each originally had their own special gifts, of speed, art or drinking (in the case of Dionysus). This misconception was useful for explaining away the odd serf who could not be suppressed in ancient times or the few poor boys who rose in rank a century ago. But then that skewed distribution of envisaged talent was reshaped as bell curved. The results of IQ tests were made into a bell-curved graph by design, but people were told (what turned out to be) the lie that the curve somehow emerged naturally.24 Apply an IQ test to a population for which that test was not designed specifically, and most people will either do very badly or very well at that test, rather than perform in a way that produces a ‘bell curve’ distribution. Tests have to be designed and calibrated to result in such an outcome. The bell curve as a general description of the population became popular as more were required to rise in subsequent decades to fill social functions that had not existed in such abundance before: engine operator, teacher, tester. Today educators are arguing to change the shape of the perceived curve of ability again, to have the vast majority of results skewed to the right, put in the region marked ‘success’, as all begin to appear so equally able. The conclusions of those currently arguing against the idea of there being especially gifted children make clear how ‘… categorizing some children as innately talented is discriminatory ... unfair ... wasteful … [and] unjustified…’.25 It contributes to the injustice whereby social inequality persists.

Although we are now almost all fed well enough not to have our cognitive capabilities limited physically through the effects of malnutrition on the brain, and more and more children are better nurtured and cared for as infants in affluent countries, and although we are now rich enough to afford for almost all to be allowed to learn in ways our parents and grandparents were mostly not allowed, we hold back from giving all children that encouragement and, instead, tell most from a very early age that they are not up to the level of ‘the best in the class’, and never can be. We do this in numerous ways, including where we make children sit at school, usually on a table sorted by ability if primary school teachers are following Ofsted guidance. Within our families all our children are special, but outside the family cocoon they are quickly ranked, told that to sing they need to enter talent shows that only a tiny proportion can win, told that to learn they need to work harder than the rest and, more importantly, that they need to be ‘gifted’ if they are to do very well.

It is now commonly said that children need to be ‘gifted’, to become Sunday’s well-developed ‘level 5’ child. They need to be ‘especially gifted’ to be that seventh of a seventh who reach ‘level 6’, and it is harder still to win a rung on the places stacked above that scale. Most are told that even if they work hard they can at best only expect to rise one level or two, to hope to be simple rather than know-nothings, or to have effective knowledge, to be a useful cog in a machine, rather than just being a ‘simpleton’ (if you do particularly well). Aspiring to more than one grade above your lot in life is seen as fanciful. Arguing that there is not a mass of largely limited children out there is portrayed as misguided fancy by the elitists. Most say this quietly, but I have collected some of their musings here, and I give many examples later in this book to demonstrate this; occasionally a few actually say what they think in public: ‘“Middle-class children have better genes”, says former schools chief, “... and we just have to accept it”’.26 Such public outbursts are not the isolated musings of a few discredited former schools’ inspectors or other mavericks. Instead they reveal what is generally believed by the kinds of people who run governments that appoint such people to be schools’ inspectors. It is just that elitist politicians tend to have more sense than to tell their electorate that they believe most of them to be so limited in ability.

You might think that what the OECD educationalists are doing is trying to move societies from extreme inequality in education, through a bell curve of current outcome, to a world of much greater equality. However, the envisaged distribution of ability is not progressively changing shape from left-skewed, to bell-shaped, to right-skewed uniformly across the affluent world. In countries such as the Netherlands, Finland, Japan and Canada people choose to teach more children what they need to know to reach higher levels. In those countries it is less common to present a story of children having innate differences. In other countries, such as the UK, Portugal, Mexico and the US, more are allowed to learn very little, and children are more often talked about as coming from ‘different stock’.27 The position of each country on the scale of how elitist their education systems are has also varied over time.

How different groups are treated differently within countries at different times can be monitored by looking at changes in IQ test results. This evidence shows that these tests measure how well children have been taught in order to pass tests. So the generation you are born into matters in determining IQ. Intelligence tests have nothing to do with anything innate. Take two identical twins separated at birth and you will find that their physical similarities alone are enough for them to be similarly treated in their schools, given in effect similar environments to each other, in a way that accounts for almost all later similarities in how they perform in IQ tests. If both are tall and good-looking, for instance, they are more likely to become more confident, receive a little more attention from their teachers, a little more praise at their performance from their adoptive parents, a little more tolerance from their peers; they will tend to do better at school. These effects have been shown to be enough by themselves to account for the findings in studies of identical twins who have been separated at birth, but usually brought up in the same country, and who follow such similar trajectories. The trajectories also tend to be so similar because, of course, the twins are brought up over exactly the same time span.28

In the US the ‘IQ’ gap between black and white Americans fell from the 1940s to the 1970s, but rose subsequently back to the 1940s levels of inequality by the start of the 21st century. This move away from elitism and then back occurred in tandem with how the social position and relative deprivation of black versus white Americans changed.29 From the 1940s to the 1970s black Americans won progressively higher status, won the right to be integrated more into what had become normal economic expectations; wages equalised a little. Then, from the 1970s onwards, the wage gap grew; segregation increased again; civil rights victories were transformed into mass incarceration of young black men. No other country locks up as many of its own people as the US. In 1940 10 times fewer were locked up in jail in the US as now, and 70% of the two million now imprisoned are black.30 This huge rise in imprisonment in the US, and its acceptance as normal because of who is now most often imprisoned, is perhaps the starkest outcome of the growth of elitism in any single rich country.

Treating a few people as especially able inevitably entails treating others as especially unable. If you treat people like dirt you can watch them become more stupid before your eyes, or at least through their answers to your multiple choice questions in public examinations. From the 1970s onwards poor Americans, and especially poor black Americans, were progressively treated more and more like dirt. Literally just a few were allowed to sing.31 To a lesser extent similar trends occurred in many other parts of the affluent world, in all those rich countries in which income inequalities grew. And they grew most where IQism became most accepted.

IQism can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you believe that only a few children are especially able, then you concentrate your resources on those children and subsequently they will tend to appear to do well. They will certainly pass your tests, as the tests are designed for a certain number to pass, and the children you selected will have been chosen and then taught to pass such tests. Young people respond well to praise to learn, and get smarter when they learn as a result. They respond badly to disrespect, which reduces their motivation to learn, so they perform badly in tests. People, and especially children, crave recognition and respect. Telling children they rank low in a class is a way of telling them that they have not earned respect. Children are not particularly discerning about what they are taught. They will try to do well at IQ tests if you train them to try to do well at IQ tests. However, almost everyone wants to fit in, to be praised, not to rank towards the bottom, not to be seen as a liability, as those at the bottom are seen.

There is a river in New Zealand called the Rakaia that is spanned by a suspension bridge of novel design. (A photograph of it is included on page ii.) There is a notice by the bridge that tells its history and that of the ford that existed before the bridge. The river is wide and fierce, draining water from the Southern Alps. The notice says that before the bridge was built, the Maori would cross the river in groups, each group holding a long pole placed horizontally on the surface of the water so that the weakest would not be swept off their feet. The notice was written by the people who came after the Maori, who knew how to build a bridge of iron supported from beneath, but who did not understand why a group of people would cross a river with a pole. It was in fact not to protect the weakest, but to protect the entire group. Any individual trying to ford a fast-flowing river draining glacial waters runs a great risk. If you hold onto a long horizontal pole with others, you are at much lower risk. The concept of ‘from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs’ was a concept that took shape in places and times when it was better understood that all benefited as a result. When crossing a freezing river with a pole, you need as many others holding onto that pole with you as can fit.

All children are different. They grow up to be adults with differing idiosyncrasies, traits (often mistaken as talents or natural endowments) both peculiar to them and peculiar to the types of societies they are raised in. Some will turn out to be considered great singers, others to sing well in choirs, if brought up where it is normal to sing. Some of these idiosyncrasies are related to physical features – taller people may have held on better to that pole, for example. Because of what was allowed at the time, and not any genetic trait, it will almost certainly have been a man, but it will not necessarily have been an especially tall man, who grew up to think of suspending a bridge across the Rakaia. Almost every adult who thinks of building a suspension bridge was a child who had seen it done before, and almost none of the children who have never seen a bridge made that way will work out how to do so without prompting by someone who has. No one had the ‘unique’ idea in the first place. Or, to put it another way, every slight change that was made, from the earliest tree-trunk bridge to the latest design, was ‘unique’, as are all our thoughts. We are, none of us, superhuman. We are not like the gods with their gifts. We can all be stupid. We hold onto the pole to cross the river having faith in the strength of others. This is a much safer way to proceed than having a few carried by others who are not joined together. If, in the short term, you value being dry above solidarity or if you are led to believe that you are destined to carry others who are your superiors, then all are at greater risk of drowning.

Before we had suspension bridges many people drowned crossing rivers. And many also died in the process of building the bridges. Suspension bridges were first built using huge amounts of manual labour to dig out the ironstone needed, and the coal to forge the iron, to construct the girders and rivet everything in place. Almost everything was originally made by hand, and even the job of constructing each rivet, as in Adam Smith’s idealised pin factory, was initially done by dividing the process into as many small processes as possible and then giving responsibility for a particular part of the work, the flattening of the head of the rivet, say, to a particular man, woman or child labourer.

When pin factories were first created they initially mostly employed adult men – it did not take much schooling to teach a man how to squash a hot rivet in a vice so that its head was flattened. It took even less schooling to teach the woman who fed him at night how to cook the extremely limited rations available to those who first worked in factories. But it took a little more schooling to teach the foreman in charge of the factory how to fill in ledgers to process orders. It took even more schooling to train the engineer who decided just how many rivets were needed to make the bridge safe. If you look at the bridge currently spanning the gorge of the Rakaia River you will see that whoever made that decision erred on the side of caution – there tend to be a lot of rivets in old bridges. A lot of rivets meant a lot of rivet makers. If reasonably fed, then rivet makers and their wives made many children, little future rivet makers, almost none of whom, living in the towns where rivets were made, grew their own food, and so there were a great many new hungry mouths to feed and not enough time or people to spare to teach most of the little ones, who, after all, were destined to make yet more rivets for yet more bridges. But incrementally a surplus of wealth was amassed and a small part of that surplus was used to build schools, especially in the countries to where most of the surplus came, such as Britain.

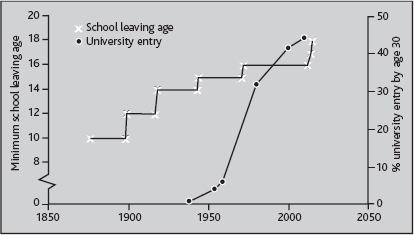

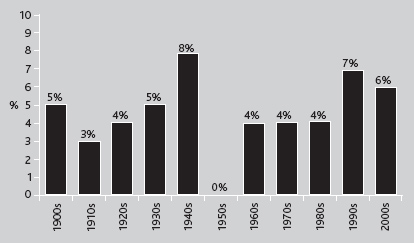

Slowly a little more time was found, won and forged out of lives of great drudgery. Women gained a little power, managed to say ‘no’ a little more, and have six children each rather than eight. By 1850 in a country like Britain, most children attended some kind of school, often just Sunday school. By the 1870s it became law that all children should attend school until the age of 10; that age was ratcheted up steadily until the 1970s, after which there was a hiatus. By the 1970s women in Britain were having on average two children with the help both of the pill and of not insignificant liberation (just a century earlier people had been imprisoned for teaching about condoms). Educational equality rose, ignorance was slowly abated, and (as fertility fell) there were fewer children to teach and it was increasingly felt that there was more to teach to all of them. But that trend of increased equality came to an end in the 1970s as 1950s elitism began to outweigh earlier progress. The latter half of Figure 3 shows, as far as university entry is concerned, a curtailing of hope and opportunity as the belief that we did not all inherently have the same potential gained sustenance from arguments over IQ and aspects of intellectual ‘potential’. Mostly recently, however, as the very final years in the figure show, those elitist arguments have been partly lost concerning school-leaving age in at least one unequal rich country – all will now be in education until the age of 18 in Britain, although whether all, if not in the ‘top streams’, will be thought educable till then and treated with respect in schools is a battle still being fought.

Increased elitism might tolerate raising the school-leaving age to 18, but it is not commensurate with providing more education for all after that. In contrast to the recent acceleration in school-leaving age, the rapid rise in university entry that peaked around the late 1960s is now decelerating, and decelerated most quickly in the most recent decade, as Figure 3 makes clear. Any further increases in school-leaving age would require compulsory university attendance, as tertiary education would be provided for all, just as secondary education was to current students’ grandparents. Comprehensive universities would be as different to current universities as comprehensive schools are to grammar schools. Such a thing is hard to imagine today, but no harder than it was to imagine compulsory secondary school attendance just one lifetime ago, and a welfare state to go with it. That welfare state was first created in New Zealand.

Sources: BBC (2007) ‘School leaving age set to be 18’, report, 12 January; Meikle, J. (2007) ‘Education dropouts at 16 will face sanctions’, The Guardian, 23 March; Timmins, N. (2001) The five giants: A biography of the welfare state (new edn), London: HarperCollins, pp 2, 73, 198 and 200); and for latest official estimates, see Higher Education Funding Council for England website on widening participation of local areas: www.hefce.ac.uk/Widen/polar/

Eventually all the great gorges had been spanned, even as far south in the world as the Rakaia River. Roads were built, agriculture further mechanised. Food was preserved, chilled, shipped abroad; mouths in Europe were fed; money from Europe was returned (with ‘interest’); within just a decade of the first IQ test being christened on the other side of the planet. Rivet making was automated. The requirement for all children in rich countries to attend an elementary school until the age of 14 was finally fully enforced, occurring less than the length of a human lifetime ago (see Figure 3). That requirement was extended to compulsory secondary education for girls as well as boys, in all affluent nations.

In early 1950s Britain, young mouths were still being fed by rations even though the war had ended. It was then that IQ tests were initially used to decide, to ‘ration’, which kind of secondary school children would be allowed to go to. Although food and education were not directly related, the ideas of how you could rationally plan the allocation of both had arisen during wartime. For education the future rationing of what were then scarce resources (graduate teachers) was based on how those children performed on one day with pen and paper at a desk around the time of their 11th birthday. For some involved the intention was altruistic, to secure the best for the ‘brightest’ of whatever background, but the result was gross injustice. Similar injustices occurred in most other newly affluent nations. These injustices were resisted, seen as segregation by ‘race’ in the US, and by social class in Britain, and within just another couple of decades almost all children went to their nearest school, with no continuing distinction between grammar or secondary modern.

The phenomenon of almost all children going to their nearest secondary school, to the same school as their neighbours’ children, had occurred hardly anywhere in the world before the 1970s. When all local children go to the same neighbourhood state school it is called a ‘comprehensive’ school because it has to provide a comprehensive education for all. The main alternatives to comprehensive schools are selective schools where most children are selected to go to a school for rejects (called ‘secondary moderns’ in Britain) and only a few are allowed to go to schools for those not rejected by a test (‘grammar schools’). Before there was a change to the system, three quarters of children would typically be sent to schools for ‘rejects’, those secondary moderns. In Britain in 1965, 8% of all children of secondary school age attended a comprehensive school, 12% in 1966, 40% in 1970, 50% in 1973, 80% by 1977 and 83% by 1981.32

It was under the Conservative administration led by Margaret Thatcher that the final cull of over a third of the 315 remaining grammar schools still functioning in 1979 was undertaken, with 130 becoming comprehensives by 1982.33 However, the Conservative government then introduced ‘assisted places’ in 1979, the scheme whereby they began to sponsor a small group of select children chosen by private schools. And so, just at the time when it looked as if divisive state education was ending, the state itself sponsored an increase in division, which was the first major increase in private school entry in Britain in decades. Britain was not alone in seeing such elitism rise.

In 1979 Britain was following events that had first had their immediate impact elsewhere. In California, where Ronald Reagan was governor until 1975 (later becoming US president in 1980), private school entry first rose rapidly after years of decline. Between 1975 and 1982, in just seven years, the proportion of children attending private schools in California rose, from 8.5% to 11.6%.34 This occurred when, as a result of Ronald Reagan’s failure to fund properly the poorest of schools before he lost office, the state reduced the funding of all maintained schools to a level near that of the lowest funded school, following a Californian Supreme Court ruling of 1976. The ruling stated that it was unconstitutional to fund state schools variably between areas in relation to the levels of local property taxes. Before the court ruling, state schools in affluent areas were better funded than state schools in poorer parts of California, just as before the abolition of almost all selective grammar schools in Britain, affluent parents whose children were much more likely to attend such schools had seen much higher state funding of their children’s education compared with that of the majority. In both the US and Britain the advent of much greater educational equality was accompanied by a significant growth in the numbers of parents choosing to pay so that their children would not have to be taught alongside certain others, nor given the same resources as those others.

The rise in private school places occurred with the fall in grammar school places in Britain, and was much greater in the US with the equalising down of state education resources in California. In Britain the greatest concentration of private school expansion occurred in and on the outskirts of the most affluent cities such as London, Oxford and Bristol – not where local schools did worse, but where a higher proportion of parents had higher incomes. Educational inequalities had been reduced to a historic minimum by the 1970s in the US, just as income inequalities had. In education this trend was turned around by the reaction to the notorious35 Serrano verses Priest California court cases of 1971, 1976 and 1977. Similarly in Britain half of all school children were attending non-selective secondary schools by 1973: again, educational inequalities fell fastest when income inequalities were most narrow. These were crucial years where issues of equality between rich and poor were being fought over worldwide as well as between local schools. Internationally, poorer countries that controlled the supply of oil worked together to raise the price of oil dramatically in that same turbulent year (during the October Yom Kippur war). International inequalities in wealth fell to their lowest recorded levels; worldwide inequalities in health reached a minimum a few years later.36 Within Britain and the US such health and wealth inequalities had reached their lowest recorded levels a little earlier, around the start of the 1970s.37 This was a wonderful time for people in affluent countries, who had never had it so good. Wages had never been as high; even the US minimum wage was at what would later turn out to be its historic maximum.38

Before the jobs went at the end of the decade, before insecurity rose, it was a great time to be ordinary, or to be average, or even above average, but the early 1970s were a disconcerting time if you were affluent. Inflation was high; if you were well off enough to have savings then those savings were being eroded. People began to realise that their children were not going to be as cushioned as they were by so much relative wealth, by going to different schools. When politicians said that they were going to eradicate the evil of ignorance by educating all children in Britain, or that they were going to have a ‘Great Society’ in the US, they did not mention that this would reduce the apparent advantages of some children. Equal rights for black children, a level playing field for poor children – these can be seen as threats as more compete in a race where proportionately fewer and fewer can win.

In 2009 the OECD revealed (through its routine statistical publications) that Britain diverted a larger share of its school education spending (23%) to a tiny proportion of privately educated children (7%) than did almost any other rich nation. That inequality had been much less 30 years earlier.

It is not hard for most people to know that they are not very special. Even affluent people, if they are not delusional, know in their heart of hearts that they are not very special; most know that they are members of what some call the ‘lucky sperm club’, born to the right parents in their turn, or just lucky, or perhaps both lucky and a little ruthless. However, you don’t carry on winning in races that have fewer and fewer winners if you don’t have a high opinion of yourself. Only those who maintain the strongest of narcissistic tendencies are sure that they became affluent because they were more able. A few of those who couple such tendencies with eugenicist beliefs think that their children will be likely to inherit their supposed acumen and do well in whatever circumstances they face. The rest, the vast majority of the rich, who are not cocksure, had a choice when equality appeared on the horizon. They could throw in their lot with the masses, send their children to the local school, see their comparative wealth evaporate with inflation and join the party, or they could try to defend their corner, pay for their children to be segregated from others, look for better ways to maintain their advantages than leaving their savings to the ravages of inflation, vote and fund into power politicians who shared their concerns, and encourage others to vote for them too. They encouraged others to vote by playing on their fears, through making donations to right-wing parties’ advertising campaigns (see Section 5.1). They convinced enough voters that the centre-left had been a shambles in both the US and the UK. The opposition to the right-wing parties was too weak, campaign funding too low, and in 1979 in Britain and 1980 in the US the right wing won.

Although not as rare as the wartime rescuers of the 1940s, the effective left-wing idealists of the 1970s were too few and far between, although there were more of these idealists in some countries than in others. In Sweden, Norway and Finland left-wing idealists won, but society also held together in Japan, Germany, Austria, Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands and France, in Spain after Franco, in Canada, to an extent in Greece (once the generals were overthrown), in Switzerland and in Ireland. It was principally in the US, but also in Britain, Australia and New Zealand, Portugal and Singapore, that those who were rich had the greatest fears, and the greatest influence. It was there that the political parties and idealists of the rich fared best. There, more than elsewhere, most who had riches and other advantages looked to hold on to them. They donated money to right-wing political parties and helped them become powerful again. They donated because they were afraid of greater equality; not because they believed that most people would benefit from their actions by becoming more equal, but because they thought that the greater good would be achieved by promoting inequality. By behaving in this way they began to sponsor a renewed elitism.

One effect of right-wing parties winning power was that they attacked trade unions. And as unions declined in strength, left-wing parties were forced to look for other sources of finance. Having seen the power of funding politics, the affluent could then be cajoled to begin to sponsor formerly left-wing and middle-of-the-road political parties and to influence them, not least to give more consideration to the interests of the rich, and because they knew right-wing parties could not carry on winning throughout the 1990s. The rich spent their money in these ways, with their donations becoming ever more effective from the early 1960s onwards.39 In hindsight it is not hard to see how the Democrats in the US and later New Labour in Britain began similarly to rely so completely on the sponsorship of a few rich individuals and businesses. Once it became common for the affluent to seek to influence politicians with money, and occasionally to receive political honours from them as a result, there was no need to limit financial sponsorship to just the right wing. In those few very unequal affluent countries where the self-serving mantra of ‘because you’re worth it’ was repeated most often, part of what it meant to be in the elite came more and more from the 1970s onwards to be seen as someone who gave money to ‘good’ causes, charities to help animals or the poor, to political parties who do the same ‘good’ works, while not altering the status quo, not reducing inequality. Inequality can be made politically popular.

In the southern states of the US the ending of slavery brought the fear of equality. Initially this was translated politically into votes for the Democratic Party and the suppression of civil rights there through to at least the 1960s, including the right for children to go to the same school as their neighbours. In South Africa in the late 1940s apartheid was introduced with popular political support from poorer whites who felt threatened as other former African colonies were beginning to claim their freedom from white rule.40 Again, segregation began at school. When Nelson Mandela was put on trial in 1963, and facing a possible death sentence, in his concluding court statement he defined, as an equality worth fighting for, the right of children to be treated equally in education and for them to be taught that Africans and Europeans were equal and merited equal attention. At that time the South African government spent 12 times as much on educating each European child as on each African child. Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990. In that year children in inner-city schools in the US, such as those in Chicago, were having half as much spent on their state secondary education as children in the more affluent suburbs to the north, and 12 times less than was spent on the most elite private school education. By 2003 almost nine out of ten of those inner-city children were black or Hispanic, and inequalities in state school spending in America had risen four-fold. Inequalities rose even further if private schools are also considered, and were still growing by 2006 as private school fees rose quickly (at the extreme exponentially) while the numbers of private school places increased much more slowly.41

Admissions to private schools rose slowly and steadily in countries like the US and the UK from the 1970s onwards. They rose slowly because few could afford the ever-rising fees and because some held out against segregating their children. They rose steadily because despite the cost and inconvenience of having to drive children past the schools to which they could have gone, parents’ fears rose at a greater rate. Rising inequalities in incomes between families from the 1970s onwards have tended to accompany increased use of private educational provision in those countries where income inequalities have increased. Rising income inequalities also increase fear for children’s futures as it is easier to be seen as failing in a country where more are paid less. It is much harder to appear to succeed where only a few are paid more.

Just as anti-colonialism and the abolition of slavery fostered unforeseen new injustices, the success of civil rights for black children in the US and working-class children in Europe in the 1960s fostered the rise of new injustices of elitism, increased educational apartheid and the creation of different kinds of schools for children seen increasingly as different, who might otherwise have been taught together. By 2002 in many inner-city state schools in the US a new militaristic curriculum was being introduced, a curriculum of fear, according to a leading magazine of the affluent, Harpers. Not a single noise is tolerated in these schools; Nazi-style salutes are used to greet teachers; specific children are specified as ‘best workers’ and, according to a headmaster administering the ‘rote-and-drill curricula’ in one Chicago school, the aim is to turn these children into tax-paying automata who will ‘never burglarize your home…’.42 In 2009 President Barack Obama promoted Arne Duncan, the man who had been responsible for education policy in Chicago at this time, to be put in charge of education policy for the nation. He may have learned from what are now widely regarded as mistakes, or he may propagate them across the country, transforming ‘schools from a public investment to a private good, answerable not to the demands and values of a democratic society but to the imperatives of the market place’.43

In Britain children placed towards the bottom of the increasingly elitist education hierarchy are not ‘rote-and-drill’ conditioned so explicitly but are instead now ‘garaged’, kept quiet in classes that do not stretch them by teachers who understandably have little hope for them. These children and young adults are made to retake examinations at ages 16–19 to keep them in the system and in education, but they are not being educated. The elitist beliefs that have been spread are that if just a few children are gifted, but most are destined for a banal future, then providing the majority with education in art, music, languages, history, even athletics, can be viewed as profligate, while such things are presented as essential for the able minority.

It is not that progress was reversed in the 1970s but that, as has so often happened before, with every two steps taken forward towards greater justice, one step is taken backwards. Ending formal slavery in the southern US saw formal segregation established, an injustice far more minor than slavery, but one that came to be seen as equally great. As the end of direct colonial rule was achieved across Africa, apartheid was established in the south, once again more minor, but colonialism at home, within a country. As segregation of children between state secondary schools in Britain was abolished during the 1970s, in the South East there was a boom in the private sector, in newly segregated ‘independent’ schooling. Thus as each great injustice was overcome, a more minor injustice was erected in its place, to be overcome again in turn as was segregation after slavery, as was apartheid after colonialism, as elitism probably will be after the latest British school reorganisation (based on renewed IQist beliefs) is abolished. In every case what had been considered normal behaviour came to be considered abhorrent: slave holding, suggesting Africans were not capable of self-rule, proposing separate but far from equal lives. Separate lives are hard to justify, from the black woman forced to sit at the back of the bus to the children who are told that the only place for them is in a sink school. Separation is not very palatable once carefully considered,.

By 2007, in some parts of the UK there were hopeful signs of a move away from seeing children as units of production to be repeatedly tested, but the English school system had become a market system where schools competed for money and children. The introduction of 57 varieties of state school saw to that, as did the expanding of private schools, which saw their intake rise to 7% while the children in these schools took one quarter of all advanced level examinations and gained over half the places in the ‘top’ universities.44 Almost all the rest of elite places in these universities go to children in the better funded of the 57 varieties of state school, or those who had some other advantage at home. Elitist systems claim to be meritocracies, but in such systems almost no one gets to where they are placed on merit, not when we are all so inherently equal. In more equitable societies numerous ‘… studies reveal the overwhelming educational and socializing value of integrated schooling for children of all backgrounds’.45

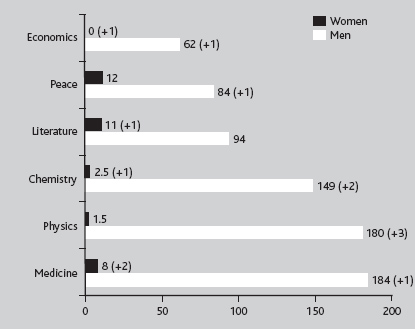

Every injustice can be paired with a human failing. The failing that pairs best with elitism, given its 1950s’ apogee, is chauvinism. This is typically a prejudiced belief in the inherent superiority of men, in particular a small selected group of men. To see chauvinism in action when it comes to elitism, all you need do is look to the top, and at the top in the field of education is the Nobel prize (although not all Nobel prizes concern education, most do). Out of almost 800 people awarded Nobel laureates by the end of 2008, only 35 of them were women, a staggeringly low 4%! Overall, more were given for work in medicine to men and women jointly than for work in any other single subject. In medicine, teamwork often involving subordination is more common, thus a significant handful of women were included among the medical laureates. Physics has lower but similar numbers of prize winners compared with medicine, but only two women have ever been awarded the Nobel prize for physics. While chemistry is fractionally more welcoming, literature is much more female-friendly, with women being awarded almost a tenth of all the prizes handed out. But given how many women are authors today, is there really only one great woman author for every 10 men? Peace is similarly seen as more of a female domain – women were possibly even in the majority as members of some of the 20 organisations awarded the peace prize over the years. But they were in a small minority of actual named winners. Prizes are very much a macho domain, as Figure 4 shows.

We know most people in the world are labelled as in some way ‘stupid’ or ‘backward’, ‘limited’ or having only ‘simple’ ability when tested by international examination (see ‘world’ histogram in Figure 2, page 47 above). What is less well known is that those not labelled ‘stupid’ have to live out lies which increase in magnitude the more elevated their status. At the top are placed mythical supermen, those of such genius, talent or potential as to require special nurturing, an education set aside. Within this set they are arranged into another pyramid, and so on, up until only a few handfuls are identified and lauded. Until the most recent generation this elite education has almost always been set aside for men. In the rare cases that women were recognised as having contributed, they were often initially written out of the story, as in the now notorious case of Rosalind Franklin who contributed to discovering the shape of the double helix within which genes are carried. Rosalind was not recognised when the Nobel prize was awarded to James Watson and Francis Crick.46

Notes: Marie Curie is split between physics and chemistry; John Bardeen and Fred Sanger are counted only once. The five prizes awarded to women and the eight to men in 2009 are shown in parentheses. The economics prize included here is the special prize awarded by the Sveriges Riksbank (see page 69).

Source: http://nobelprize.org/index.html

Nobel prizes in science are the ultimate way of putting people on pedestals and provide wonderful examples of inherent equality when it comes to our universal predisposition to be stupid. In his later years James Watson provided the press with a series of astounding examples of this, for instance saying, it is claimed, that he had hoped everyone was equal but that ‘… people who have to deal with black employees find this not true’.47 This is no one-off case of prejudice among prize winners. Around the time that Watson was being given his laureate for double helix identification, a physics laureate of a few years earlier, William Shockley, was advocating injecting girls with a sterilising capsule that could later be activated if they were subsequently deemed to be substandard in intelligence, in order to prevent reproduction.48 Francis Crick’s own controversial support for the oddly named ‘positive eugenics’ was also well recorded by 2003, if not so widely known and reported in the popular press.49

James Watson’s work was mainly undertaken at the University of Cambridge and William Shockley ended up working at Stanford University in California. Perhaps we should not be surprised that men with backgrounds in the sciences who were educated and closeted in such places as Cambridge or Stanford should come to hold the view that so many not like them are inferior. Why should someone who examines things down microscopes or who studies x-rays know much about people? Surely, you might think, those who might have been awarded a Nobel prize in social sciences, the arts or the humanities might be a little more enlightened, and so the academics in these areas often appear to be, but perhaps only because in these fields there are no such prizes and so no such prize holders to be put on pedestals from which to confidently pontificate.50