The news commentators come on and they act like we’re totally stupid and they have to interpret everything.

—fifty-seven-year-old Kentucky resident1

The press should report the news instead of making the news.

—sixty-year-old Indiana resident2

We need less emphasis on the sensational.

—eighty-year-old North Carolina resident3

ILL WORDS FOLLOWED George W. Bush as he traveled the campaign trail. On the network evening news, Bush’s coverage was 63 percent negative in tone and only 37 percent positive.4 Major newspapers gave him an equally rough ride—more than 2 to 1 percent negative coverage.5 Everything from his interpersonal skills to the way he ran his campaign came under attack. When it was revealed that the word “rats” was embedded as a frame within a Bush campaign ad targeted at Al Gore, a voter interviewed on the CBS Evening News said: “When I heard that ‘Rat’ thing, the first thing that came to mind was Nixon and Watergate.”6

To die-hard Republicans, Bush’s negative coverage represented just another bashing by the liberal media. Ever since the writer Edith Efron charged in 1968 that the television networks had “actively opposed the Republican candidate, Richard Nixon,”7 Republicans have believed that the media favor the Democrats. In 2000, the Republican national chair, Jim Nicholson, sent the telephone numbers of network anchors Dan Rather, Peter Jennings, and Tom Brokaw to party activists so that they could call to complain about Bush’s coverage.8

However, if the press favors the Democrats, why did it also bash Al Gore? On the nightly news, Gore’s coverage was substantially more negative (60 versus 47 percent) than Bush’s during the primaries and almost as negative (60 versus 63 percent) during the general election.9 Gore, like Bush, was raked up one side and down the other. On NBC News, a voter was heard to say: “My biggest concern is that Al Gore will say about anything he needs to say to get elected President of the United States.”10

The news media were showing their bias, but it was not a liberal or a conservative one. It was a preference for the negative. Often, the more highly charged the subject, the more one-sided is the portrayal. A good deal of Bush’s coverage during the 2000 election suggested that he was not too smart. There were nine such claims in the news for every contrary claim. Gore’s coverage was dotted with suggestions he was not all that truthful. Such claims outpaced rebuttals by seventeen to one.11

Studies reveal that this negative tendency is not limited to presidential candidates. When a president’s approval rating drops, it gets more news coverage than when it rises.12 When policy programs fail, they receive more news attention than when they succeed.13 When public officials misbehave, they get more coverage than when they triumph.14 The press, said the scholar Michael Robinson, seems to have taken some motherly advice and turned it upside down: “If you don’t have anything bad to say about someone, don’t say anything at all.”15

Some journalists claim it has always been that way and that Washington, Jefferson, Jackson, and Lincoln endured far worse, but this is not the case.16 Although many early newspapers could be downright nasty, they were partisan journals that heaped on praise as they dished up criticism.17 Rather than the claim that “they’re all a bunch of bums,” the partisan press was based on the premise that the bums were all on the other side. In 1896, the San Francisco Call devoted 1,075 column inches of glowing photographs to the Republican ticket of McKinley-Hobart and only 11 inches to the Democrats, Bryan and Sewall.18 San Francisco Democrats had their own bible, the Hearst-owned Examiner, which touted William Jennings Bryan as the savior of working men.

Partisan journalism slowly died out in the early 1900s and a more neutral form replaced it. The critical style, in turn, gradually overtook its predecessor. Political coverage started to become more negative in the 1960s, and by the 1980s attack journalism was firmly in place.19 The tendency was interrupted by periodic bouts of patriotism. The press did an abrupt shift whenever the United States faced an international threat—for example, the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979, the bombing of the marine barracks in Lebanon in 1983, the Gulf war in 1990–91, the Balkan air wars of the 1990s, and the war against terrorism that began in 2001. Each time Americans rallied around the flag, so, too, did the press. NBC outfitted its peacock logo with stars and stripes following the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks, and computer-generated flags festooned the other networks. Nevertheless, the long-term tendency has been decidedly negative.

The impact has been substantial. The news provides a day-to-day window on the world of politics. Not that Americans accept the press’s version of reality in its entirety. Audiences filter the news through their personal needs, interests, prejudices, attitudes, and beliefs. Yet the media supply most of the raw material that goes into people’s thinking about their political leaders and institutions. In this sense, politics is a secondhand experience, lived through the stories of journalists.

What people receive through that window affects how they respond to politics. If the portrayal is inviting, they will be encouraged to get involved and pay attention. But if it’s disheartening, they will maintain their distance and disengage. Therein lies the significance of negative news.

The American press today is at a crossroads, as it wrestles with intense audience competition and the lessons learned from its performance before and after the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks. Analysts differ on how they think the press will operate next year, much less five years from now. In The News About the News, Leonard Downie, Jr., and Robert G. Kaiser express pessimism about journalism’s near future.20 In The Elements of Journalism, Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel express guarded optimism.21 But some of what lies ahead will be affected by tendencies developed in the past. The story of modern political journalism begins near the time that voting rates started to slip.

“THE AIR WAS THICK with lies, and the president was the lead liar,” said the Washington Post’s editor, Ben Bradlee.22 Watergate and Vietnam are now distant enough that it’s easy to misjudge just how much courage and tenacity the press mustered in the face of serious government threats and abuses of power.23 The investigation of the Watergate break-in and the publication of the secret Pentagon Papers were risky undertakings but, ultimately, journalism’s finest hour. This moment also marked a turning point in the relationship between the press and politicians. Journalists believed they had let the country down by taking politicians at their word, and they vowed not to let it happen again.

Although Vietnam and Watergate altered the relationship between the press and politicians, an earlier and less heralded development also contributed to the change. This development started innocently enough, at the time the television networks decided they could make money by expanding their news programming.

During the 1950s the network newscasts were inconsequential. They were short, blatantly commercial (The Camel [cigarette] News Caravan), and consisted mainly of headline news gathered by newspapers and wire services. In 1963, however, the networks introduced the thirty-minute newscast and launched picture-centered news. They quickly discovered that the print style of reporting was poorly suited to a visual medium. Viewers didn’t have to be told what they could see with their own eyes. Moreover, straightforward description seemed dull when told to a viewing audience. A livelier, more structured style of reporting built around story lines was needed.24 Reuven Frank, executive producer of NBC’s nightly news, told his correspondents: “Every news story should, without any sacrifice of probity or responsibility, display the attributes of fiction, of drama. It should have structure and conflict, problem and denouement, rising action and falling action, a beginning, a middle and an end.”25

An interpretive style of reporting that was explanatory as well as descriptive began to emerge.26 With the old style, the journalist’s job was to transport the audience to the scene of an event and describe what had happened. The new style, however, asked the journalist also to serve as an analyst, telling the audience not just the “what” of an event but the “why.” News reports became news stories.

Newspapers slowly followed suit.27 Morning papers could not survive if they simply retold events that people had heard about the night before on the evening news. Print journalists would have to explain, analyze, and interpret, going deeper into events than television’s time constraints allowed.

If this was all that interpretive journalism represented, it would have been an inconsequential development. But it served gradually to shift control of the news to the journalists. Newsmakers held the upper hand with the old form. The journalist’s task was to describe events, which typically meant telling the audience what newsmakers had said and done. “It is my job,” said an influential journalist, “to report the [newsmaker’s] words, whether I agree with them or not.”28

Interpretive journalism altered that requirement. Newsmakers’ actions would still make the news and even provide many of the headlines and story leads, but the message itself would be shaped by the interpretation the journalist imposed on events.29 Instead of simply reporting events, the raw material would be repackaged with the journalist, not the newsmaker, at the center.30

The change did not take place all at once. Vestiges of the old form clung for a long time, particularly in print reporting. Even as late as the 1972 presidential campaign, newspaper reporters were laboring under its constraints. “[We were] caged in by the old formulas of classic objective journalism, which dictated that each story had to make some neat point; had to start with a hard news lead based on some phony event that the candidate’s staff had staged,” wrote the journalist Timothy Crouse. “If the candidate spouted fulsome bullshit all day, the formula made it hard for [us] to say so.”31

Interpretive journalism offered a way out, and television journalists were already wriggling free. Their reporting showed signs of the change that was to come. When George McGovern appeared unannounced at New York’s Columbus Day parade during the 1972 campaign, for example, CBS’s news story was filled with sly put-downs (“Marchers grumbled that politicians ought to go find their own fun and leave other people’s parades alone”) and crafty asides (“A Republican dignitary huffed and puffed about the political impropriety of turning up at parades without an invitation”).32

The “wrap” to a story became the television correspondent’s sharpest weapon. Some stories in the 1960s did not even have a wrap-up comment by the reporter. By the late 1970s, all of them did,33 often in the form of a put-down.34 Reporters were ten times more likely to close a story with an assertion than with a fact.35 CBS’s Bernard Goldberg, for example, concluded a 1980 election story by saying the candidate’s campaign was following “the path of Skylab—the orbiting satellite that had crashed to earth.”36 Politicians were nearly powerless to affect such reporting. Interpretive journalism gave reporters the last word.

Newsmakers eventually became like Victorian children, seen but seldom heard. In 1968, when presidential candidates appeared in a television news story they were usually pictured speaking. Two decades later, when they were visible on the screen with their mouths moving, their words in most cases could not be heard; the journalists were doing the talking.37 In 1968, the average “sound bite”—a block of uninterrupted speech by a candidate on television news—was more than 40 seconds.38 By 1988, the average had shrunk to less than 10 seconds.39

For every minute that Bush and Gore spoke on the evening newscasts during the 2000 campaign, the journalists covering them spoke for 6 minutes.40 The two candidates received only 12 percent of the election coverage. Anchors and correspondents took up three-fourths of the time, with the rest allocated to other sources, including voters, experts, and group leaders. A viewer who watched the network news every evening between Labor Day and Election Day would have heard 17 minutes each from Bush and Gore, or about 15 seconds a night.41 When Bush appeared on CBS’s David Letterman show on October 19, he received nearly as much airtime as he did on the CBS Evening News during the entire general election.42

Newspapers have also squeezed out the newsmakers. In 1960, the average continuous quote or paraphrase of a newsmaker’s words in a front-page story was 20 lines. By the 1990s, the average had fallen to 7 lines, usually in paraphrased form.43 It is now rare for a newsmaker to be quoted at length in a newspaper story.

As the first signs of this new journalism surfaced in the early 1970s, some in the profession expressed concern. The Washington Post editor Russell Wiggins regularly told his reporters: “Journalists belong in the audience, not on the stage.”44 But his view was eclipsed by the lessons of Vietnam and Watergate.45 Journalists had concluded, says the scholar Michael Schudson, that “there is always a story behind the story, and that it is ‘behind’ because someone is hiding it.”46

Although the full impact of interpretive journalism was not immediately apparent, a few observers thought it would be substantial.

The analyst Paul Weaver believed political news would be dominated by stories of strategy and infighting. Because journalists tend to see politics as a competitive struggle for power, he believed they would interpret the news primarily through that lens, which would alter the content of news. Although newsmakers think strategically, their rhetoric is aimed at public policy, which, in descriptive reporting, had placed issues at the forefront of the news. With interpretive reporting, the journalists’ rhetoric—that of the “strategic game”—would take center stage. Policy issues and debates, Weaver said, would become “noteworthy only insofar as they affect, or are used by, players in pursuit of the game’s rewards.”47

In a study of television’s 1972 election coverage, Robert McClure and I found that Weaver’s hypothesis was more than a hunch. As reported on television, that election was a spectacular struggle: rapid followers, dramatic do-or-die battles, strategy, tactics, winners and losers. Far down the list were issues of policy and leadership. “The contest theme,” our study concluded, “was carried to the campaign’s very end, at the expense of the election’s issues and the candidates’ qualifications for office.”48

But it was Michael Robinson, then at Catholic University and later at Georgetown, who put his finger on what would become the new journalism’s major legacy: negative reporting and jaded citizens. Writing in 1976, Robinson argued that television’s preference for crisis, conflict, and drama, when combined with journalists’ “negativist, contentious, or anti-institutional bias,” would result in deeply skeptical reporting. Political leaders and institutions would be relentlessly criticized, fueling public disaffection. Robinson offered persuasive though inconclusive survey and experimental evidence to back up his thesis, which he labeled “videomalaise.”49

A study of ninety-four newspapers conducted shortly thereafter by the University of Michigan’s Arthur H. Miller, Edie N. Goldenberg, and Lutz Erbring indicated that print coverage might have the same effect. They found that readers exposed to newspapers which had a “higher degree of criticism directed at politicians and political institutions were more distrustful of government and [had] higher levels of cynicism.”50

Perhaps even more so than Vietnam, Watergate made a deep impression on reporters. Watergate quickly became the prevailing myth of journalism.51 Reporters believed that the press had saved American democracy and that it had a continuing responsibility to protect the public from lying, manipulative politicians.

The watchdog role was an old one, but Watergate gave it an urgency that changed even the basic assumptions of journalism. Politicians would no longer be taken at their word.52 Reporting would be rooted in the assumption that officials could not be trusted.53 If politicians were willing to lie to the media, their every word would be subject to scrutiny. Newsweek’s Meg Greenfield said journalists had previously believed “the worst thing we could do … was [to] falsely accuse someone of wrongdoing.” Now, “the worst, the most embarrassing, humiliating thing is not that you accuse someone falsely but that you … fail to accuse someone of something he ought to be accused of.”54

Some journalists, including Greenfield,55 were uncomfortable with the change and concerned about its consequences, but their view was a minority one, particularly among network correspondents. Although there had always been prominent journalists, such as Walter Lippmann and the Alsop brothers, television had a way of making celebrities of quite ordinary reporters. Network correspondents were inflated by the public’s sense that anyone on television had to be important. The temptation to rise above the story was irresistible. The wall that had separated reporting and editorializing was collapsing.56

But how can the journalist act aggressively in the context of the humdrum of everyday public affairs? “How does one,” as an aspiring investigative reporter asked a U.S. senator, “hunt people like you?”57 Wrongdoing on the scale of Watergate is exceedingly rare, and investigative journalism in any case is slow and painstaking. It’s no simple matter to uncover a politician’s true motives or to verify rumors of wrongdoing. Even if one tries, the truth may be so fragile or the trail so cold that, in the end, there is no story to tell.

An everyday alternative to investigative journalism was needed, and by the late 1970s reporters had found it. When a politician did something newsworthy, they turned to his adversaries to tear it or him down. It was an old technique, but it became a constant practice.58 The critical element was supplied, not by careful investigation of whether a politician was sincere or a proposal was sound, but by inserting a contrary opinion. “You come out of a legislative conference and there’s 10 reporters standing around with their ears twitching,” said U.S. Senator Alan Simpson. “They don’t want to know whether anything was resolved for the betterment of the United States. They want to know who got hammered, who tricked whom. … They’re not interested in clarity. They’re interested in confusion and controversy.”59 Conflict, always an element of political coverage, became its theme. The level of conflict in congressional coverage rose sharply in the 1970s and the 1980s.60

By the mid-1980s, journalists often did not even bother to find someone to express the opinions they wanted to voice. They had become critics in their own right.61 They were careful to avoid the appearance of taking sides in policy disputes over issues such as abortion and health care. But they didn’t hesitate to weigh in on questions of character and competence. A study of 1988 election coverage found that television journalists spent three-fourths of their airtime “evaluating what was right, good, or desirable” and only one-fourth providing factual information.62

Seldom were reporters’ judgments based on thorough investigation. Many were rooted in the assumption that politicians are self-serving.63 Sometimes, a commonplace event was made into a news story only by the “edge” that the journalist gave it.64 When George Bush traveled in his shirtsleeves by bus through Illinois during the 1988 campaign without subjecting himself to a press conference, ABC’s Brit Hume suggested that Bush’s casual attire was a ruse. Bush might have appeared like “a man in tune with rural America,” but his posh bus “had a microwave oven [and] a fancy restroom.” Hume wrapped up his report with a second put-down: “Polls show Bush behind in Illinois and he apparently thought getting out among the people would be just the thing. Did that also mean that he would answer reporters’ questions? Not today. After all, you can carry this accessibility stuff too far.”65

Critical journalism had become like a drug. Reporters were routinely sticking needles into the nation’s highest leaders. It was exhilarating and, once experienced, it was hard to stop. Vice President Dan Quayle delivered a half-hour speech on moral values that included a one-sentence criticism of the unwed television character Murphy Brown for “bearing a child alone and calling it just another ‘lifestyle choice.’” The comment produced front-page stories and, in the tabloids, mocking headlines: “Quayle to Murphy Brown: ‘You Tramp’” (New York Daily News). At a White House press conference called to discuss U.S.-Canada trade, journalists ignored both the trade issue and Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney, pestering Bush about Quayle’s statement, all the while implying the vice president lacked the brains to separate fact from fiction.66

Politicians were easy targets. The breakdown of comity in Congress made it simple for journalists to find lawmakers who were willing to say nasty things about a politician of the opposite party, and sometimes even about a member of their own party. The gridlock that sometimes tied up policy initiatives for months on end added substance to the press’s claim that politicians were self-serving.

Politicians had come to distrust the press.67 Some, like Bush, despised it. At his 1992 campaign stops, Bush drew loud cheers whenever he waved a bumper sticker that read, “Annoy the Media, Re-Elect George Bush.”68 There was, said Senator Simpson, “a total disregard and distrust by politicians of the media and a total cynicism and distrust of politicians by the media.”69 Politicians and journalists had become locked in what the ethicist Sissela Bok calls a “vicious circle.”70

The old journalistic adage “bad news is good news” had become an imperative. Skepticism had been part of reporting since at least the turn-of-the-century muckraking period. As the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Frank Simonds had said in 1917: “There is but one way for a newspaper man to look at a politician, and that is down.”71 But the muckrakers had focused on systemic corruption: the taking of bribes, the exploitation of ethnic and religious prejudice, the unholy alliance between politicians and the business trusts. Modern journalists were tearing into politicians for everything from their clothing to their accessibility. There were larger issues, too, including Iran-Contra, the savings-and-loan crisis, and institutional gridlock, but attack journalism had become the domineering style.72 In 1989, more than a thousand charges of ethical impropriety (sex was the leading category) were leveled at members of Congress on the nightly newscasts.73 “I feel like bait rather than a senior member of Congress,” said a U.S. representative.74

Bill Clinton did not even get the “honeymoon” that newly elected presidents had come to expect. His news coverage was 57 percent negative during his first two months on the job. Six months into his presidency, Clinton’s numbers were even worse—66 percent negative.75 According to the press, Clinton was doing almost everything wrong. A series of controversies, including the president’s $200 haircut and his “gays in the military” initiative, had led reporters to speak of “amateur hour” at the White House.76 Some of this criticism was on target, but much of it was not. Clinton’s first-year achievements included a deficit-reduction program, a family-leave program, banking reform, NAFTA, a college-loan program, the Brady bill, and AmeriCorps. Since 1953, Congressional Quarterly has tracked congressional backing of legislation on which the president has taken a position. Congress backed Clinton on 88 percent of contested votes in 1993, a level exceeded only twice in the previous forty years—by Dwight Eisenhower in 1953 and Lyndon Johnson in 1965.77

Clinton’s reward? Enough negative news to power a magneto. But it was no worse than the coverage Congress was getting. The 103rd Congress (1993–94) enacted a score of new programs but failed to pass health-care reform and was called “pathetically unproductive” in a New York Times editorial.78 Network coverage of the Democratic-led 103rd Congress was nearly 70 percent negative in tone.79 Network coverage of the Republican-led 104th Congress was also nearly 70 percent unfavorable, despite the historic first one hundred days in which many of the planks in the GOP’s Contract with America were fulfilled. A poll during the 1994 election indicated that 97 percent of Washington journalists regarded the contract as “a campaign ploy.” When it turned out to be something quite different, they criticized Republicans for trying to ram it too quickly through Congress.80

Coverage of national politics was so downbeat that it distorted Americans’ sense of reality. A 1996 survey asked respondents whether the trend in inflation, unemployment, crime, and the federal budget deficit had been upward or downward during the past five years. There had been substantial improvement in all of these problem areas, but two-thirds of the respondents said in each case that things had gotten worse.81 What could explain such widespread ignorance except the cumulative effect of daily news that highlighted the failings of national policy and leadership?82

Politicians, no doubt, also contributed mightily to the public’s perception that government wasn’t working. Conservative lawmakers were consciously seeking to drive down confidence in government in order to create support for their effort to roll back federal economic and social programs. For their part, liberal lawmakers found fit to attack government over issues that dealt with the regulation of personal conduct. The gap between these sides was often so wide that lawmakers in the middle had no hope of filling it, which fed the growing perception that government was bogged down in partisan bickering and policy deadlock.

But journalists also were working from a mindset that cast an unfavorable light on nearly all things political. For example, the 1996 GOP nominating race was, according to press accounts, a virtual bloodbath. NBC’s Lisa Myers called Forbes “Malcolm the Mudslinger,” saying, “With ads like [his], Forbes may find it tougher to persuade voters he’s all that different from those career politicians [he’s running against].” Ninety-nine percent of journalists’ coverage of the candidates’ advertising campaigns was about their use of negative ads. Most of the sound bites aired on the evening newscasts showed one candidate attacking another. The 1996 GOP race, however, had a rather different look from ground level. The media analyst Robert Lichter examined the GOP hopefuls’ television ads and stump speeches. Over half the ads (56 percent) were positive in tone, and nearly two-thirds (66 percent) of the assertions in the candidates’ speeches were positive statements about what they hoped to accomplish if elected. This dimension of that campaign, however, was seldom mentioned in news reports. “Forget about the issues,” ABC’s Peter Jennings said of the Republican race, “there is enough mud being tossed around … to keep a health spa supplied for a lifetime.”83

During the Watergate era, critical journalism had been a means by which the press could hold politicians accountable. Now it was an end in itself. Criticism was the starting point in the search for and crafting of news stories. It was also the path of advancement. Coveted appearances on network and cable talk shows were granted to journalists adept at sharp-edged commentary. The measured voices in the Washington press corps could still be heard, but cable television had created a lot more seats at the table. The nation’s “fourth branch” was now as entrenched as the officials it covered. Journalists had established themselves as a counter-elite operating within the tidy confines of Washington, as insular as the politicians they criticized for having lost touch with the public they serve.

In the view of David Broder, the dean of Washington journalists, the press had spun out of control. “Cynicism is epidemic right now,” he wrote. “It saps people’s confidence in politics and public officials, and it erodes both the standing and standards of journalism. If the assumption is that nothing is on the level, nothing is what it seems, then citizenship becomes a game for fools, and there is no point in trying to stay informed.”84 The warning did not slow the flow of negative news, which suited some journalists just fine. Expressing her enthusiasm for a “raffish and rowdy” press, the New York Times’s Maureen Dowd said journalists had exposed politicians for the scoundrels they were.85 When journalists were asked in a 1995 Freedom Forum/Roper poll whether the public’s mistrust of Congress was due primarily to the press or to Congress itself, thirty-six times as many of them pointed the finger at Congress.86

By the early 1990s, the major barrier to the flow of political criticism was a cutback in political reporting. Public-affairs coverage was being reduced to make room for “soft news.”

Soft news was a response to the competitive environment created by cable television. The number of American homes with cable had jumped from fewer than 10 percent in the 1970s to more than 50 percent by the early 1990s. In the process, the broadcast networks lost their monopoly on the dinner-hour audience. By 1995, in the face of competition from cable’s entertainment programs, the evening news audience had shrunk by a third.87 Newspaper readership was also declining, for the first time ever except during hard economic times.88

A historic reversal was taking place. For 150 years the news audience had expanded. Fewer than 5 percent of Americans in the early 1800s received the daily news. The invention a few decades later of the hand-cranked rotary press drove the price of a paper down from five cents to a penny and newspaper readership began to increase, propelled also by rising literacy. Near the end of the 1800s, the invention of newsprint and the steam-driven press enabled metropolitan dailies to sell as many as 100,000 copies a day. Radio news came along in the 1920s, and television news followed in the 1950s. By 1980, 75 percent of adults were partaking of daily news. But, suddenly, the trend had reversed. The news audience was shrinking.

News organizations’ initial response was to cut costs. Foreign news bureaus were among the first things to go. The public presumably didn’t care all that much about international news, much less about its quality.

When news audiences continued to shrink, many media outlets opted for a market-driven style of news intended to compete directly with cable entertainment programs. Commentators coined the terms “infotainment” and “news lite” to describe it. Within the news business, it was commonly called soft news to distinguish it from traditional hard news (breaking events involving top leaders, major issues, or significant disruptions to daily routines).

The market strategy was not exactly new. Jacked-up stories of crime, exotic places, celebrities, and medical breakthroughs had been prime weapons in the circulation wars that big-city newspapers waged in the early 1900s.89 The yellow-journalism era, a newspaper historian wrote, featured “a shrieking, gaudy, sensation-loving, devil-may-care kind of [reporting that] lured the reader by any possible means.”90 Named after the Yellow Kid, a cartoon character used to attract readers, yellow journalism became synonymous with the worst kind of reporting.91

Yellow journalism eventually blackened the press’s reputation, and some observers believed that history was repeating itself as a result of cable competition. “The networks now do news as entertainment,” said former CBS anchor Walter Cronkite. “[It is] one of the greatest blots on the recent record of television news.”92 NBC’s Tom Brokaw defended it, saying that the networks cannot “commit suicide.”93 He argued that soft news was an inevitable adjustment to changing news tastes and habits. “What we are doing is not being the wire service of the air anymore,” Brokaw said. “We’re picking four or five topics and trying to deal with them in a way that people can feel connected to.”94 Former Federal Communications Commission chairman Newton Minow had a less flattering depiction of the trend, calling it “pretty close to tabloid.”95

The indisputable fact was that the news had softened considerably. A study by Harvard University’s Shorenstein Center showed that celebrity profiles, lifestyle scenes, hard-luck tales, good-luck tales, and other human-interest stories rose from 11 percent to more than 20 percent of news coverage between 1980 and 1999. Stories about dramatic incidents—crimes and disasters—also doubled during this period. The number of news stories that contained elements of sensationalism jumped by 75 percent.96

As soft news took up more space, public-affairs coverage dwindled. “Public affairs used to be at the core of the news,” said media analysts Robert Lichter and Jeremy Torobin. “Now it is one niche in a news agenda oriented more toward features and lifestyle issues.”97 From 1980 to 2000, public-affairs stories decreased from 70 percent of news coverage to 50 percent.98 Nearly every area of public affairs, including national and international politics, was cut back. In 1977, one in three Time and Newsweek covers had featured national and international leaders. By 1997 that proportion was one in ten. Meanwhile, covers that featured sex or a sexy celebrity rose from one in six to one in three.99

Political scandal posed the one exception because it fused hard news with soft. With roots in money, sex, power, intrigue, and wrongdoing, scandals provided a basis for both attack and titillation. According to one study, scandal coverage in major news outlets jumped from 2 percent of the news in 1977 to 13 percent in 1997.100

President Clinton became the main focus. Most Americans’ first real awareness of him came on January 23, 1992, when Gennifer Flowers claimed a twelve-year relationship with the Arkansas governor. Some journalists later said they didn’t want to carry the story, but a hundred showed up at a Clinton campaign stop that first day to question him about her.101 The next day, five hundred turned out for a Flowers press conference at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.102

But the Flowers story was just a tease. In the aftermath of the Monica Lewinsky affair, which was real enough, it is easy to overlook just how fully Clinton’s earlier coverage was driven by alleged wrongdoing. Most of these scandals were what Michael Robinson calls “medialities”—press-driven controversies of little merit.103 White House counsel Vince Foster’s death in the end was what police said it was from the start, a suicide. Nevertheless, it prompted hundreds of insinuating stories. “Filegate” and “Travelgate,” which were in and out of the news for seven years, were also much ado about not all that much. “Trooper-gate” had a basis, but the allegations were so confounded by their right-wing sponsorship that fact and mischief were at times hard to distinguish. The Arlington National Cemetery scandal, in which grave plots were reportedly traded for campaign donations, was the nation’s top story until it was shown to have no basis. The Whitewater affair was, of course, the granddaddy of them all. Compared to Watergate in a New York Times feature article in 1994,104 it had an eight-year run in the news before being dismissed in 2000 by the Special Prosecutor’s Office. When Whitewater surfaced early in the Clinton presidency, it received three times as much news coverage as the leading policy issue of the time, health-care reform.105

So much has been written about the Lewinsky coverage that little needs to be said here except to note how fully it embodied what Marvin Kalb calls “the new news.”106 When the Lewinsky story broke, facts and rumors merged. In Warp Speed, the journalists Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel report that only 26 percent of the allegations were attributed to named sources as opposed to anonymous or unnamed sources. Only 1 percent of the charges were based on two or more named sources.107 Some allegations proved to be accurate (for example, the claim of a semen-stained dress) and some did not (for example, the claim that a White House steward had witnessed a sexual liaison). Truth and speculation were tossed together in what was surely the decade’s biggest political story, but what, in its reporting standards, was sadly ordinary. Kovach and Rosenstiel said ABC News, which broke the blue dress story, was lucky rather than good in its scoop because it had no firm confirmation of the allegation’s accuracy108

The Lewinsky story resembled the Watergate story but was rooted in a different brand of journalism. The Washington Post was more than fifty stories deep into its Watergate coverage before it made a substantial allegation that turned out to be factually wrong. The Post’s Ben Bradlee insisted that any allegation had to be confirmed by at least two independent sources before going to print. “We could not afford any mistakes,” he said.109 That standard had evaporated long before the Lewinsky story broke. Early in the Whitewater story, the Wall Street Journal had urged reporters to throw caution to the wind, saying the benefits would outweigh the costs of false allegations.110

A variation of Parkinson’s Law was at work. Allegations large and small were inflated to fill available news time. Round-the-clock cable news had accelerated the news cycle and increased the demand for controversy. In the intensely competitive media environment, the pressure of running a story had eclipsed the old standard of getting the story right.

DURING THE LAST three decades of the twentieth century, the news was relentlessly negative, carrying public opinion along with it. The Vietnam and Watergate period was not the high mark of critical reporting and public mistrust but, instead, the point of departure for an increasingly assertive press and an increasingly jaded public.

Five presidents in a row after Nixon received reams of bad press.111 Clinton’s coverage was the most negative, but even the president who fared best, Gerald Ford, did not fare well. Reporters joked that Ford (a gridiron star at the University of Michigan) had played too many football games without a helmet and reveled in showing him tripping on stairs or falling on ski slopes—metaphors for their belief that he was overmatched by the demands of his office.

Congress fared no better.112 Press coverage of the institution was steadily negative after the early 1970s, regardless of which party controlled it or how much or little was accomplished.113 In the 1972–92 period, allegations of personal impropriety (financial dealings, sexual antics, and the like) rose from 4 percent of congressional coverage to 17 percent—one in every six stories.114 “Over the years,” concluded the scholar Mark Rozell, “press coverage of Congress has moved from healthy skepticism to outright cynicism.”115

News of the presidency and Congress, however, was rosy compared with that of federal agencies. A study of news coverage in the early 1990s, for example, found that every high-profile agency except the Department of Defense had received more negative than positive coverage. The State Department’s coverage was only 13 percent positive, and the Justice Department’s was just 10 percent favorable.116

Public mistrust and dissatisfaction accompanied the flow of negative news. In 1964, 16 percent had said they trusted the national government to do the right thing “most of the time”; in 1994, only 21 percent held this opinion, the lowest level ever recorded.117 The “Harris Confidence Index,” based on people’s confidence in leaders of the nation’s major institutions, fell by more than half between 1966 and 1997, when it hit its lowest level ever.118

It was not a coincidence that, as the news soured during the post-Watergate period, Americans’ beliefs about their leaders and institutions also soured. The decline in public confidence was not solely attributable to attack journalism, but the tone of the news was too negative for too long not to have made an impression. By choosing to present politicians as scoundrels who do not deserve the public’s trust, the press helped bring about that very opinion.119

Studies documented the connection. One found that negative images of presidential candidates increased in lockstep with the increase in negative coverage of these candidates during the 1960–92 period.120 Another study showed a close relationship between presidential approval ratings and the tone of presidential press coverage.121 Still other studies documented a linkage between negative news and negative impressions of Congress and other institutions.122

These findings were supported by the results of experimental research.123 In the most comprehensive of these studies, the University of Pennsylvania’s Joseph Cappella and Kathleen Hall Jamieson demonstrated that messages cast in the media’s primary frames—conflict, strategy, and ambition—bring out feelings of mistrust.124 The message as opposed to the medium is the critical element. “The effect,” Cappella and Jamieson write, “occurs for broadcast as well as print news, and when the two are combined, the combination is additive.”125 Negative news, they conclude, generates “cynical responses to politicians, politics, governance, campaigns, and policy formation.”126

Critical journalism did not by itself drive down public trust in the post-Watergate period.* Scandals, policy failures, and Washington infighting also contributed. Although the period was generally marked by peace, prosperity, and racial and gender progress, major setbacks occurred, including double-digit inflation, the Iranian hostage crisis, Iran-Contra, the savings-and-loan debacle, and the Lewinsky affair.127 Social disruption was also a factor. Changing lifestyles and mores contributed to a decline in personal trust and respect for authority,128 which affected how Americans saw all institutions, including political ones.129 The number who believed “most people can be trusted” fell from 58 percent in 1960 to 37 percent in 1993.130

But journalism, too, was part of the problem. For years on end, journalists chose to tell their audience that their leaders were self-interested, dishonest, and dismissive of the public good.131 It was a one-sided story that had a predictably negative effect on Americans’ beliefs about their leaders and institutions.

This one-sided, negative story also had a corrosive interest on voter participation. The mistrust it bred has contributed to the decline in turnout. A hint of that influence surfaced in our Vanishing Voter surveys as Election Day neared. We asked nonregistrants and likely non-voters to respond to a list of possible reasons for why they would not vote. Included on the list were such standard items as “because I’ve been so busy that I probably won’t have time,” “because I don’t have any way to get there,” “because I moved and haven’t registered at my new location,” “because I’m not a U.S. citizen,” “because I’m not very interested in politics,” and “because I don’t like any of this year’s presidential candidates.” Also included on the list was an item that measured political dissatisfaction: “because I’m disgusted with politics and don’t want to be involved.”

“Disgusted with politics” came out at the top of the nonregistrant list and second on the nonvoter list. Thirty-eight percent of nonregistrants said that disgust with politics was a reason they were not enrolled, which ranked ahead of being busy (34 percent), not being interested (31 percent), and not being satisfied with the candidates (27 percent). Among registered voters who said they intended to sit out the election, 37 percent claimed political dissatisfaction as a reason, which ranked behind a lack of interest (46 percent) but ahead of being busy (28 percent) and not being satisfied with the candidates (29 percent).

Without doubt, these responses reflect a degree of rationalization. People who do not intend to register or to vote for other reasons may use disgust with politics as an excuse to hide those reasons. But analysts who say that all such responses are rationalizations would have to make the implausible argument that campaigns are different from all else in life. Any time an activity disgusts or discourages people, some recoil. That’s true of employment, religion, family relations, schooling, and other areas. Why is voting a special case? An indication that it is not a special case is apparent in the responses of those in our pre-election surveys who said they “might not vote.” They, too, could have blamed it on dissatisfaction with politics. However, only 8 percent did so. Much higher on their list was the claim that they might be too busy to turn out. That’s a reasonable response from someone still weighing the decision to vote, just as it’s reasonable that political dissatisfaction could underlie a firm decision not to vote.

Nevertheless, a more precise test of the relationship between political dissatisfaction and voting was also conducted. Respondents were asked a strongly worded survey question (“Do you agree or disagree that most politicians are liars or crooks?”) that was designed to identify those with a high level of mistrust. The fact that nearly as many respondents (44 percent versus 56 percent) agreed that “most politicians are liars or crooks” was itself indicative of just how far political dissatisfaction had spread. But was this attitude related to turnout? Did those who expressed mistrust participate at a substantially lower rate in the 2000 election than the others? In fact, they did. They were 13 percentage points less likely to vote. The difference is statistically significant even when income, education, or age is taken into account.* Let there be no mistaking the finding: mistrust undermines the desire to vote.

Some of the respondents who claimed politicians are not trustworthy fit the profile of the alienated citizen. They are, as the Washington Post’s Richard Morin and Claudia Deane describe them, “the angry men and women of U.S. politics.132 But most of the respondents who expressed mistrust did not fit the profile. They are disenchanted rather than alienated. They are not fuming mad at government, and, unlike the alienated, they tend to believe that government has an interest in their opinions and their welfare. But they are disenchanted with how politics is conducted. If the alienated are angry, the disenchanted are weary. They express dismay at the bickering they associate with Washington politics, at the flow of special-interest money, at the scandals that seem to routinely envelop those in power, at the strategic maneuvering that often appears to win out over the public good, and at the spin that journalists and politicians put on issues and events. Said one of our survey respondents: “I’m just disgusted with politics in general these past years.”133 Politics itself is not their gripe. It is the practice of politics to which they object, and it discourages some of them from voting.134

These people are a new type of nonvoter. Traditionally, nonvoters have divided into three types. One is the alienated: those who are politically angry or bitter. A second type is the apathetic: those who have little interest in politics. They were and still are the largest nonvoting group. They find politics to be dull and boring, and most of them admit to not understanding it very well. They are not particularly mistrustful of politics and politicians; in fact, they are about as trusting as those who do vote. What keeps the apathetic from participating is that they don’t care much for politics or know much about it. Many of the apathetic nonvoters have low levels of education and income. The third traditional type of nonvoter is the disconnected: those who are unable to participate because of advanced age, disability, or temporary ineligibility for reasons such as a recent change of address.

There is now an identifiable fourth type, the disenchanted. They are the nonvoters who have been spawned by the political gamesmanship and negative news that dominated late-twentieth-century politics. Many of them express interest in public affairs, talk occasionally about politics, and keep up with the news. In fact, the Vanishing Voter surveys show they do not differ greatly from voters in these respects. Nor do they differ significantly from voters in terms of years of education. Where they differ is in their disgust with the way that politics in the United States is conducted, which leads some of them to stay away from the polls on Election Day.

The political mistrust that emerged from the discouraging tone of news and politics in recent decades has mainly affected young and middle-aged adults. Among our respondents thirty-four years of age and younger, those who agreed that “most politicians are liars or crooks” were 17 percentage points less likely to vote in 2000 than those who disagreed. Among adults between the ages of thirty-five and fifty-four, the difference was 12 points. Among those fifty-five and over, it was only 7 points. For this last group, moreover, the relationship dwindled to insignificance when education or income was controlled, whereas it remained statistically significant among middle-aged and young adults.*

These differences help to explain a contradictory conclusion from studies based on elections in the 1980s and earlier. Although rising political cynicism, as one of these earlier analysts said, seemed “tailor-made for explaining declining voter turnout,”135 research failed to show a clear connection between the two.136 On the basis of their analysis of the 1952–88 presidential elections, Steven Rosenstone and Mark Hansen concluded: “Neither feelings of trust in government nor beliefs about government responsiveness have any effect whatsoever on the likelihood that citizens will vote or will take part in any form of campaign politics.”137

Our 2000 Vanishing Voter surveys, however, provide evidence of the linkage.* Why the difference? Why should political dissatisfaction have contributed to lower turnout in 2000 when it did not appear to do so even as late as 1988? The answer lies in part in the cumulative effect of political mistrust. It ordinarily takes time for a change in people’s attitudes to produce a change in their behavior. And even if behavior is altered, the initial response is often tentative, which can go undetected by the relatively crude measures and methods available to electoral analysts. Adjustments were undoubtedly occurring in citizens’ participation patterns as a result of rising levels of mistrust in the 1970s and 1980s, but they were not yet robust enough to be easily detected. More to the point, by 2000 Americans had been exposed to additional years in which their already battered trust in politics was battered further by a seemingly unending string of scandals and the deafening crescendo of attack journalism. If some of them were not ready to retreat to the sidelines by the 1970s and 1980s, they had gone that way a decade or two later.

The answer also lies, as it often does in such cases, in what people experienced as children and young adults rather than what they experienced later in adulthood.138 By the time people are in their thirties, many political inclinations have taken root and do not change much later on. Voting is one of these inclinations, at least for most. Although people often vote with greater frequency as they age, the inclination to vote—and typically, the first actual vote—occurs within the first decade or so of eligibility139 Most individuals who are committed to the process by then participate with some regularity throughout their adult lives, regardless of ensuing developments.

The point of vulnerability is childhood and early adulthood, before a voting inclination has been established. A boost or disruption at this stage can tip the individual toward or away from a lifetime of voting. The early experiences of the two most recent generations of adults— the newest one and the baby boomers who preceded them—were much different, and much less favorable to the development of a voting habit, than the childhood experiences of the World War II generation that came before them.

Consider first the formative years of the World War II generation. Although many never completed high school, the war and its aftermath gave them an unrivaled civic education. News, as they recall it, did not play a large part in childhood, but political discussion and a drummed-in sense of civic duty did.140 By midlife, roughly three in four voted regularly, and they have continued to participate at high rates. Vietnam and Watergate disillusioned some, but, with the possible exception of the 1972 election, these developments did not diminish their interest in voting.141

By comparison, the baby boomers—the oldest of whom came of voting age in the late 1960s—had a bittersweet political youth. As children, they knew a nation where the public trusted and admired political leaders. Many baby boomers also recall a childhood where news and political discussion were an everyday part of home life. But they also experienced the Kennedy and King assassinations and Vietnam. The war disillusioned many of them, and they were then blindsided by Watergate, which was followed by the era of attack journalism.

The most recent generation, those under thirty-five at the time of the 2000 election, grew up in homes where interest in news and politics was waning. They had no defining issue on the order of the Depression, World War II, the civil rights movement, or Vietnam. There was no military draft to embrace or avoid and no protest march to join or jeer. The top issues of their childhood were fleeting and remote from their daily lives: the Iranian hostage crisis, Iran-Contra, the Gulf war, and the Lewinsky affair. Even the defining event of this generation— terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon—was experienced through television and came late in their formative years. Their youth was steeped in political scandal and attack journalism.

Unlike the World War II generation, the most recent generation and the baby boomers did not have deeply positive experiences to cushion the impact. Negative messages rained down on them as young adults and, in the case of the most recent generation, even in childhood, which contributed to their dissatisfaction with politics. Older Americans were not oblivious to the change in the tone of news and the conduct of politics. They, too, grew increasingly dissatisfied. But their participation pattern was largely set. Not so for the baby boomers and, even more, those of the most recent generation. Some of them gave in to their mistrust, turning away from the voting act. As one of our Vanishing Voter survey respondents said: “Politics is just not something that interests me.… That’s pretty much true of the people I went to school with. None of us votes.”142

Earlier studies did not detect the link between voting and dissatisfaction because they stopped with the elections of the 1980s, just as the cumulative effect of changing demographics and chronic mistrust was beginning to mount. There is today a measurable difference between the voting rates of those young and middle-aged Americans who are less trusting of politics and those who are more trusting, and it persists even when education and income differences are taken into account. These nonparticipants are a reason that turnout has stagnated or declined despite the rising level of education, which should have boosted it. Heightened mistrust has worked to hold down the voting rate.

Other influences, too, have served to weaken participation among younger adults, and scholars are divided on the degree to which the long-term voting trend is attributable to generational replacement. The political scientists Warren Miller and Merrill Shanks claim it has been the driving force in the downward trend,143 a view shared by Robert Putnam.144 Other scholars claim the generational effect is smaller. Wayne State University’s Thomas Jankowski and Charles Elder, for example, argue that age may have had less influence on the decline than institutional changes have had.145 What most scholars do agree upon is that since the 1970s succeeding groups of first-time eligible voters have voted at a lower rate than the preceding group.*

What our research demonstrates is that political mistrust has contributed to this development.* Young and middle-aged adults are not necessarily more mistrustful than older ones, but unlike them, their mistrust has translated into a reduced tendency to vote.

SOFT NEWS also diminishes politics. This type of news, as the writer Paul Weaver notes, is so irrelevant to our public life that it gives the public little reason to get involved.146

The press has a responsibility to provide a view of the world that does not lead people to think they are in the Land of Oz when they are traveling through Kansas. News that highlights unusual incidents is disorienting, even to the point of warping one’s sense of reality. Few developments illustrate this issue more than the public’s response to the “if it bleeds, it leads” reporting of the early 1990s. Crime news tripled in 1992 and 1993. On network television, it accounted for 12 percent of the coverage, overshadowing all other issues, including the economy, health care, and the Bosnian crisis.147 The focus continued into 1994. The nightly newscasts aired more stories on crime than on the economy, health-care reform, and midterm elections combined.148 “Lock ’Em Up and Throw Away the Key: Outrage Over Crime Has America Talking Tough” was Time magazine’s cover story of February 7, 1994.

The coverage had a dramatic impact on public opinion. At no time in the previous decade had even as many as 8 percent named crime as the nation’s most important problem. In 1994, however, an astonishing 39 percent said it was the country’s most pressing problem.149 Unfortunately, the public was responding to media portrayal rather than to reality. Justice Department statistics show that the level of crime, including violent crime, had been dropping for three years. Public opinion was being driven by news images and was, in turn, driving public policy. Responding to growing concern with crime, state and federal officials enacted tough new sentencing laws and began building prisons at the fastest rate in the nation’s history. Six years later, the United States had a larger portion of its population behind bars than any other country in the world.

Public discourse is also impoverished by soft news. Much of what people talk about when their thoughts turn to public affairs is based on what they have just seen or read in the news. As the journalist Theodore H. White noted: “The power of the press is a primordial one. It determines what people will think and talk about.”150 If people are steeped in entertainment and distracted by news of remote or titillating incidents, civic life suffers. The media theorist Neil Postman asserts that, as a public, we risk “amusing ourselves to death.”151

The diminution of political news itself signals that politics is a marginal activity, as even election coverage indicates. In 1992, the nightly newscasts carried 728 campaign stories during the general elections. The networks averaged 8.2 minutes of coverage per night. In 1996, the number of election stories fell to 483. The coverage dropped again in 2000, to 462 stories, even though the campaign was more competitive than the one in 1996. The networks averaged only 4.2 minutes of coverage a night.152 The decline was even sharper in the nominating stage. Although both parties held contested races in 2000 (only the GOP had one in 1996), network coverage in the pre-convention period was down by 33 percent.153 During one stretch the custody fight over Elián González garnered the Cuban boy twice as much airtime on the evening newscasts as was received by front-runners Bush and Gore combined.154

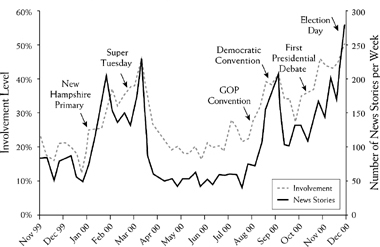

The decline in election coverage had the effect of reducing Americans’ involvement in the 2000 campaign. As election coverage rises and falls, so, too, does the level of campaign interest. Our Vanishing Voter surveys reveal a close association between the ups and down in the amount of coverage and the ups and downs in involvement (Figure 3.1). As coverage rises, people increasingly think and talk about the campaign. As would be expected, they also are more likely to report having seen, read, or heard election news stories. Of course, the public’s attention and the media’s coverage are responsive to many of the same developments in the campaign. The October debates, for example, provoke heightened discussion even apart from the heavy coverage they receive. But even during quieter moments of the campaign, heavier coverage stimulates interest. If the coverage in 2000 had been as heavy as it was in 1992, people would have talked and thought more about the campaign. As a result, they also would have been better informed about the candidates and issues.155 Turnout might also have been marginally higher in 2000 if news coverage had been heavier. Our Vanishing Voter surveys indicate that, as campaign involvement increases, the number of people who say they intend to vote also increases.

FIGURE 3.1

CITIZEN INVOLVEMENT AND ELECTION NEWS

The heavier the election coverage, the more involved people are in the campaign, as measured by how much they talk, think, and attend to news about it. (See Appendix for information on how citizen involvement during the campaign was measured.)

THE EXCESSES of post-Watergate journalism may have exhausted themselves with the feeding frenzy that was the Gary Condit story. For nearly four months in 2001, it dominated our national news, a distinction earned not by Representative Condit’s stature—he was a backbench member of the House—or by new developments—the known facts changed hardly at all during the story’s run. The story’s prominence owed to its ingredients—power, sex, and mystery. Even though the D.C. police repeatedly told reporters, on the record and off, that Condit was not a suspect in Chandra Levy’s disappearance,156 the odd chance that he could resolve the mystery kept the story alive.

Condit was the subject of hundreds of news reports and talk-show programs before his story abruptly disappeared. It was not that charges against him had been dropped; they had never been filed. It was not as if Levy had been found; she was still missing. Reality had intruded. The Condit frenzy stopped at precisely 8:46 a.m. on September 11, 2001, the moment that the first hijacked airplane hit the World Trade Center in New York City.

This time, the press rose to the occasion. At a cost of hundreds of millions in direct expenses and lost advertising revenues, the media made a supreme effort to get abreast of the story. In the weeks and months that followed, Americans received information they had never heard before about Islam, Afghanistan, the Taliban, Pakistan, global terrorism, Al Qaeda, and homeland security.

A troubling question was why the press had not awakened earlier. Several months before the terrorist attacks, the U.S. Commission on National Security, which was headed by former senators Warren Rudman and Gary Hart, issued a comprehensive report predicting a “catastrophic attack” by international terrorists and urging the creation of a homeland security agency. CIA director George Tenet had also issued a warning, saying at a Senate hearing that Osama bin Laden’s “global network” was the “most immediate and serious” threat facing the country157 Except for a few publications, such statements were considered too boring or remote to deserve attention. In the year preceding the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks, the Al Qaeda terrorist network was mentioned by name only once on the network evening newscasts.

International coverage had been pruned to make room for soft news. A study of ten daily newspapers found that foreign news had declined to 3 percent of total coverage in the period before the terrorist attacks.158 Even the networks and most major newspapers had cut foreign news by a third or more.159 Former U.N. ambassador Richard Holbrooke said, “The media’s role in the last decade was grossly irresponsible, because the stories mattered.”160

The closing of foreign news bureaus had also left the media unprepared to report accurately on the terrorist threat. Virtually no U.S. journalists were stationed in Afghanistan or neighboring Pakistan when the attack occurred. “From our flag-decorated TV screens,” wrote the New York Times’s Frank Rich two weeks after the bombings, “you would hardly know that the Taliban’s internal opposition and our would-be fellow freedom fighters, the ragtag Northern Alliance, is anathema to Pakistan, our other frail new ally. Or that Pakistan and its military, with its dozens of nuclear weapons, are riddled with bin Laden sympathizers.”161 Gradually, the press gained control of the international aspects of the story, but it was a rocky start.

Although it is unreasonable to expect the press to shoulder the full burden of an informed public, it is reasonable to expect the press to provide a window on the world of politics that is clear enough to illuminate that world. Therein lies a major failing of journalism in recent decades. It misled Americans about the nature of political reality, both at home and abroad.

The mainstream press is at a crossroads that will decide its future and affect the quality of the nation’s civic life. The press must decide whether to proceed along the negative and soft news paths it has tread so heavily or to take a newer and more constructive road, such as the one so earnestly pursued in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks.

False choices can blind journalists to their options. Should the media defer to or attack those in power? When the issue is framed this way, any self-respecting journalist has only one choice: attack.

However, it is the wrong choice because it is the wrong question. Knee-jerk criticism only weakens the press’s watchdog capacity. When the press condemns everything and everyone, audiences will shun the messenger. Such was their response to the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal. Even though the press suggested that the president would have to resign (“his presidency is numbered in days,” said ABC’s Sam Donaldson),162 the public wasn’t buying. The news coverage was so sensational and so deeply rooted in hearsay that most Americans supported Clinton, though not his behavior. Having barked too loud for too long, the watchdog had lost its bite.

In effect, the press had squandered its moral authority. During the Watergate period the press was one of the nation’s most trusted institutions. Two decades later it was one of the least trusted. A 1998 Pew Research Center poll indicated that 63 percent of Americans believed that the press “gets in the way of society solving its problems.” A 1998 Gallup poll found that journalists’ reputation for honesty was as low as that of the politicians they covered and just above that of lawyers and building contractors. A 2000 National Public Radio (NPR) survey found that only one in five citizens had “quite a lot” of confidence in the news media. Without moral authority, the press cannot be an effective watchdog. What Alexander Hamilton said of the judiciary’s power—“it has only judgment”—applies also to the press.

The proper exercise of that judgment would benefit the press in more ways than one. An irony of attack journalism is that, as it erodes the foundation of political involvement, it also eats away at the foundation of news consumption. As politics becomes less attractive to people, so, too, does the news. Individuals who have a weak interest in politics are five times less likely (15 percent to 84 percent) to regularly follow the news than those with a strong interest.163

Critical reporting needs to give way to a more constructive form. Journalists should not ignore official wrongdoing, nor should they turn their agenda over to the newsmakers. But they should give proper voice to the newsmakers, pay sufficient attention to what government does well, and assess politicians’ failings by reasonable standards. The challenge is to strike the proper balance. Before Watergate and Vietnam, newsmakers had far too much control over the news, contributing to an arrogance of power that had tragic consequences. But the pendulum then swung too far in the journalists’ direction.

A second false choice is that between informing and entertaining the news audience. Should the press give its audience what they want or should it give them what they need? This question assumes that audience wants and needs are opposites. The public could not have realized before September 11 that it needed to know more about the global terrorist threat. Had it known more, it might well have wanted more. “This business of giving people what they want is a dope pusher’s argument,” said Reuven Frank, former president of NBC News. “News is something that people don’t know they’re interested in until they hear about it. The job of the journalist is to take what’s important and make it interesting.”164

Catering to what people want also assumes that what they want initially is what they will want in the end as well. Although marketing studies indicate that soft news has appeal, what is not known is whether it can hold an audience over the long run.165 A 2000 study by Harvard University’s Shorenstein Center found that soft news can alienate the hard-news consumers who are the core audience.166 The recent experience of NPR also suggests that a soft-news strategy might be shortsighted. With a 300 percent increase in audience in the past decade, NPR has defied the downward trend.167 Although NPR relies on features as well as hard news, its features tend to be interpretive of hard-news events. NPR has become a haven for hard-news consumers dissatisfied with other broadcast outlets.168

The picture, admittedly, is not as clear-cut as the NPR case might suggest. The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer on PBS has lost a significant part of its audience during the past decade. Moreover, some soft-news television stations have risen to the top of their local markets. On the other hand, the Project for Excellence in Journalism, which tracks the content and audience ratings of 146 local television news programs, has found that hard-news formulas currently seem to work best. Nearly two-thirds of the highest-quality news programs have had a ratings increase in recent years, a higher percentage than any other type of news program, including those that load up on sensational stories of crimes, fires, and accidents.

It is still too early to conclude with certainty that soft news is a weak base upon which to build a loyal audience. Nevertheless, if people are looking primarily for entertainment, they ultimately can, and likely will, find something more amusing than news, however soft it might be. Heavy doses of soft news may even wear out an audience, just as the best sitcoms eventually lose theirs. A NewsLab study of former or less frequent viewers of local TV news found that many of them had simply tired of the soft-news formula: “too much crime” and “too many fluff stories” were among the top reasons respondents gave for paying less attention.169

In contrast, hard news is an ongoing public-affairs story affecting all of us. For more than a century, it has been the reason that millions each day choose to invest some of their time following the news. Hard news, by illuminating today’s events, builds interest in tomorrow’s. Of course, even ardent hard-news consumers enjoy the occasional amusing or shocking story, but that is different from placing such stories at the center of news coverage.

The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001 resurrected news and politics in the nation. Within a few weeks, confidence in journalists and political leaders reached heights not seen in decades. It also awakened many in the news business and in politics to their civic responsibility. But will the new spirit last? Six months after September 11, many news outlets had reverted to their soft-news and hard-ball formulas.170

One should not underestimate the difficulty of reforming institutions as large and complex as the press. A century ago, the press faced a comparable challenge when it confronted the excesses of yellow journalism. Two decades lapsed before journalists figured out how to juggle the quest for profits with their public responsibility. If a major transformation of today’s media lies ahead, it will not occur overnight.

Yellow journalism was quieted in part by the demise of enough daily newspapers to relieve the competitive pressures that were driving it. Today, with digital television entering the media market, competitive pressures can be expected to intensify, which will severely test any attempt to develop a more responsible form of journalism. A case in point is ABC’s attempt to dump Ted Koppel’s Nightline in favor of the Late Show with David Letterman, even though the change would not have greatly increased the network’s audience.

Audience competition will also intensify because of young adults’ declining interest in news. About half of them pay little or no attention, and no more than a fourth regularly attend to news coverage. Unlike the baby-boom generation that preceded them, they did not grow up in the era when television sets across America were routinely tuned to the evening newscasts at the dinner hour. Entertainment programming was available at all hours, and it dominated their after-school viewing. Few children have an interest in news, but, if exposed to it regularly from an early age, they may develop one. Without this type of exposure, they are only half as likely by adulthood to have acquired an interest in news.171 With no change in sight in children’s viewing habits, the news media will find themselves fighting over fewer and fewer customers.

That will be a blow to politics as well as to news. The news is a day-to-day instrument of democracy. Unless people partake of it regularly, they are unlikely to be politically aware or interested. There is something worse than exposure to persistently negative news, and that’s no news exposure at all.

Many journalists are determined to change the situation. The Committee of Concerned Journalists, for example, includes more than a thousand reporters and editors from around the country who are committed to restoring traditional news values. They will need help in achieving their goal. Most news organizations today are embedded in huge corporations that are driven by the bottom line. As the Washington Post’s Leonard Downie, Jr., and Robert G. Kaiser note, news departments are under enormous pressure to keep the earnings coming.172 Owners who recognize that the news is more than just another commodity are needed. Audience demand must also change. However much Americans may complain about the news, they do not always show a preference for quality reporting. Schools should be encouraged to promote a news habit as a duty and a pleasure, so that the demand for better news will grow in the years ahead.173

But journalists, too, will have to rethink how they define themselves. The Washington press corps particularly has developed values and interests that do not coincide with those of their readers and viewers. In many newsrooms, journalists are admired for being tough on politicians and are considered wimps if they are not. Audiences can be wooed momentarily by disdain and inside dope, but these also contain the seeds of discontent. The journalist’s voice is heard above even that of the newsmaker, and put-down, not purpose, is too often the order of the day. Elections seem to bring out the worst of it. “I know a lot of people who are thinking about this election the same way they think about the Iran-Iraq war,” wrote Meg Greenfield in 1980.174 “They desperately want it to be over, but they don’t want anyone to win.” George Will said much the same thing in 1992: “The congestion of debates may keep these guys off the streets for a few days. When they emerge from the debates, November—suddenly the loveliest word in the language— will be just around the corner.”175 Shortly before Election Day in 1996, Tom Brokaw opened his newscast by remarking: “If this campaign has an unofficial motto, it is this—wake me when it’s over.”176

What are citizens to do? Cast as voyeurs in a world distant from their own, they have backed away from politics and from news. In the long run, this doesn’t serve anyone’s interest, as the Columbia School of Journalism’s James Carey so pointedly says:

Journalism and democracy share a common fate. Without the institutions or spirit of democracy, journalists are reduced to propagandists or entertainers. When journalists measure their success solely by the size of their readership or audience, by the profits of their companies, or by their incomes, status, and visibility, they have caved into the temptation of false gods, of selling their heritage for a potage.… 177