September 2, 2010, was the day Mohammed Amin, a Taliban leader in the northeast Afghan province of Takhar, was supposed to die. His death would not come as a total surprise to anyone, least of all him, as the odds against his survival had definitely been lengthening. Given his position as Taliban deputy shadow governor for Takhar, Amin, an ethnic Uzbek in his forties, had strong grounds for believing that he occupied an uncoveted slot on the Joint Prioritized Effects List (JPEL), as the U.S. kill-roster was officially termed, and was therefore ripe for execution by air strike via drone, helicopter, bomber, or a Special Operations night raid whenever the opportunity arose. The recently installed U.S. commander, General David Petraeus, had expanded the list and doubled the number of such raids as one of his first acts upon arriving in Kabul. The death toll had shot up accordingly: 115 across the country in July 2010 and 394 in August. Indeed, on the very day Amin was to be killed, Petraeus told reporters that special forces operations in Afghanistan were “at absolutely the highest operational tempo,” running at four times the rate ever reached in Iraq.

“Petraeus knew he was only going to be there a short time, a year or so,” a close adviser to the general while he was in Afghanistan told me. “What could he do that would enable him to present good numbers to Congress in a year? The easiest way to generate good numbers was by killing people.”

The renewed emphasis on high-value targeting in Afghanistan, which had already increased tenfold since Stanley McChrystal took over theater command in 2009, had a certain irony. As we have seen, the post-2001 insurgency and revival of the Taliban had to a considerable degree been caused by an obsessive hunt for Taliban and al-Qaeda leadership figures. But the surviving al-Qaeda members had decamped to Pakistan, along with the Taliban leadership. The Taliban remaining in Afghanistan had for the most part retired to private life and wished only to be left alone, resisting initial calls from Pakistani intelligence to start a jihad against the Americans.

Most Afghans were relieved to be free of their incompetent and fanatical rulers and welcomed the Americans and British. However, the dearth of genuine targets was relieved by warlords and others seeking favors from the country’s new masters. Feeding the demand for targets, they fingered business rivals, tribal enemies, and other unfortunates who were duly rounded up and shipped off to the torture chambers at the Bagram base outside Kabul or the oubliette of Guantánamo. Unsurprisingly, this state of affairs, combined with the kleptocratic behavior of the U.S.-installed government, eventually provoked a fierce reaction and a revival of the Taliban. So now, to deal with this insurgency, the United States was embracing the very tactic that had generated the problem in the first place. High-value targeting had in any case become especially fashionable in senior military circles thanks to the glow of the apparent victory over al-Qaeda in Iraq, spearheaded by JSOC’s industrial counterterrorism, and backed by massive troop reinforcements and a shower of cash for Sunni tribal leaders willing to change sides. In addition, the rough-and-ready methods deployed in Afghanistan in 2002 had been replaced by the systematized approach developed in Iraq. Instead of the hit-or-miss dependence on tip-offs from warlords, the JPEL was now largely reliant on the presumed certainties of technical intelligence, principally in the form of drone surveillance (i.e., “the unblinking eye”), the monitoring of phone traffic, and the physical location of phones via their signals.

Mohammed Amin qualified for the list on at least two counts. Apart from his Taliban leadership status, a death warrant in itself, he was also listed as the leading member in Afghanistan of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, a jihadi group centered in that neighboring country but also active in Afghanistan.

Even so, securing a place on the JPEL had not been a casual affair. A “Joint Targeting Working Group” composed of representatives of various operational commands and intelligence agencies met once a week to vet the “targeting nomination packets.” As of October 1, 2009, there had been 2,058 names on the JPEL. Execution, in every sense of the word, was primarily the responsibility of Joint Special Operations Command, though in keeping with convention this group was operating in Afghanistan under a code name, which in this period was Task Force 373 (as opposed to Task Force 11, as it had been known in the days of Operation Anaconda). Even in internal classified documents, the involvement of this roving death squad in killings around Afghanistan was deemed highly sensitive, to be concealed at all costs.

The carefully selected and highly trained task force rank and file tended to take a cynical view of the overall utility of their operations. “They’d come into my province, work their way down the JPEL, but they knew and I knew that all those names on the list would be replaced in a few months,” a former U.S. official who worked closely with them in Afghanistan told me. Then he mentioned a phrase that seems to come up a lot in the targeted-killing business: “They called it ‘mowing the grass.’”

Further up the chain of command, there was at least the pretension that the selective killing fit into an overall plan. Petraeus’ “Counterinsurgency Field Manual” instructed intelligence analysts to recommend “targets to isolate from the population, and targets to eliminate.” In the cross hairs were the supposedly critical nodes in the enemy system, which the analysts clearly regarded as akin to a corporate hierarchy helpfully subdivided into specialties such as leader, facilitator, mayor, IED expert, shadow governor, deputy shadow governor, chief of staff, military commission member, financier, and so on.

Along with “leaders,” “facilitators” were a heavily targeted category, these being variously defined either as people who provided safe houses and support, or merely influential people, village elders and landowners who had no choice but to cooperate with the Taliban. Casting doubt on the precision of the undertaking was the fact that public announcements, in the form of ISAF press releases, regarding successful operations (never mentioning the task force role) often tended to describe the same person as both a “leader” and a “facilitator.”

As a deputy shadow governor, Mohammed Amin certainly qualified for a place, complete with four-digit designating number, on the Joint Prioritized Effects List. Once on the list, it remained only for the task force to locate and kill him. His movements between Pakistan and Takhar may have been furtive, but to the “unblinking eye” of ISR, that was irrelevant. All they needed was a phone number.

Just as in Iraq, where the introduction of cell phones had enabled both the insurgents, who used them to communicate and to detonate bombs, and their hunters, who used them to locate and track their quarry, cell phones have played a vital role in the Afghan war ever since they were introduced in 2002. In fact, so crucial was Afghan phone traffic to U.S. intelligence—one in every two Afghans has a cell phone—that it has been credibly reported that the NSA recorded every single conversation and stored them for five years. Just as the Constant Hawk and Gorgon Stare programs had been attempts to look into the past, Retro, as the comprehensive phone-call recording program was called, was a way of listening to the past. Collecting numbers was therefore a high priority involving such devious maneuvers as turning a blind eye to cell phones used by insurgent prisoners in the giant Pol-e-Charkhi jail on the edge of Kabul and other Taliban holding pens around the country. The Taliban, meanwhile, were not unaware of the keyhole that cell phones exposed to the enemy. In an attempt to neutralize their adversary’s advantage, in 2009 they launched a campaign to destroy the system and did indeed blow up over three hundred cell towers, only to abandon the effort thanks to either popular complaint or irritation at the consequent inconvenience to themselves.

Knowing a person’s cell-phone number allows anyone with access to a country’s cell phone network—no problem for Special Operations in Afghanistan—to obtain the phone’s International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) number. With this in hand, the phone, or more specifically its SIM card, can not only be intercepted but also tracked within a hundred meters just by triangulating signals from cell towers. But that is not close enough to fix someone in a specific car in a moving convoy, at least not in a remote region, such as the bare hills of Takhar, in northern Afghanistan. A very precise fix on a phone and therefore its owner required the device that mimics cell towers, variously known as Stingray, Triggerfish, or IMSI Catcher, which had already done McChrystal such good service in Iraq.

Sometime in early July 2010, the task force scored a breakthrough, arresting a man who revealed that he was a relative of Mohammed Amin and obligingly furnished his phone number. With this in hand, the trackers were swiftly able to locate Amin’s IMSI number and thus fix at least the general location of the SIM card, assumed to be in close proximity to its owner.

In the early summer the SIM-card trackers registered that Amin was in Kabul, making and receiving calls to and from locations around the country, all of which were submitted to the exotic algorithms of social-network analysis, tracing and measuring the links of his network both as a Taliban leader and as a leader of the Uzbek Islamists. At some point the watchers noted that Amin was now calling himself Zabet Amanullah—clearly an alias, they assumed—on the phone.

Later in July, the card began moving north, out of Kabul and up to Takhar. In those wide-open spaces Amin would be that much more vulnerable to a strike, and since he was already on the list, it only remained to choose the method and place to kill him. Technically, JPEL designees are liable for kill or capture, but as subsequent events indicated, no one was too interested in capturing the Taliban official.

On September 2, the perfect opportunity arose. The SIM card, and therefore the phone it was in and the person carrying that phone, set out early in the morning from a district in Takhar called Khwaja Bahuddin and headed west. Streaming video from a drone showed a convoy of six cars passing through mountains and making occasional brief halts during which people apparently carrying weapons got out of the cars for a minute or so. The drone could carry an IMSI Catcher, so on video screens at JFSOC headquarters and at Hurlburt DCGS in Florida—and perhaps on multiple additional screens across the neural net of ISR—the crucial SIM card signaled the car in which it was riding. Eventually the convoy rolled into an area of bare, low hills with occasional defiles.

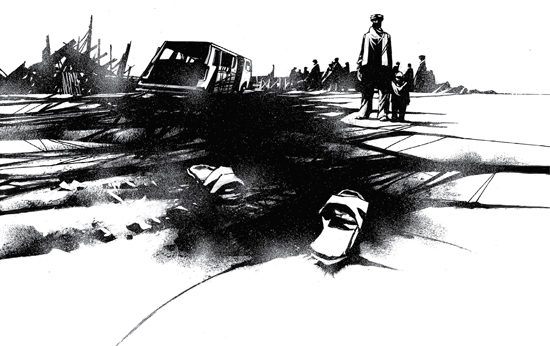

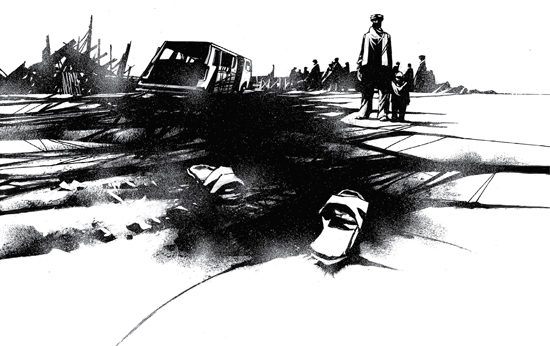

A little after 9:00 a.m., as the first two vehicles moved out of one of these narrow passes, two fighter jets detailed for the operation began the attack. The first bomb landed beside the target vehicle, gouging a crater in the road five feet across and eighteen inches deep and flipping the vehicle over on its side. The watchers saw “dismounts” run from the other vehicles, turn the target vehicle right side up, and help passengers get out. A second bomb hit ten minutes after the first, this time landing directly on the target vehicle. The explosion blew apart at least seven people, leaving severed legs, arms, and other body parts strewn around the wreckage.

The planes dropped another bomb ten minutes later and another ten minutes after that. The lengthy intervals, atypical of normal bombing tactics, signified the time it took for the analysts to locate the target phone via the IMSI Catcher on the drone circling overhead. But the bombs were ineffective: one exploded harmlessly on the hillside, and the other, a dud, hit the road some distance away and failed to explode. Adopting a different approach after the second miss, the commander directing the operation ordered two helicopters, “Little Bird” MH-6s, to finish the job. Accordingly, while one circled, the other dropped down low and hovered just above the ground, allowing the crew a clear view of survivors milling around the car. “It seemed as if the helicopter pilot had a picture … in his hand,” a survivor later recalled, surmising that he was looking for a particular target. Finally he loosed off a burst of machine gun fire that put a bullet right through the face of the man holding the phone. Then he began to move, circling around to take a closer look at the bodies and survivors from the rest of the convoy. The helicopters stayed on the scene for another hour before returning to base, leaving ten people dead at the scene. It had been a textbook targeted killing.

That same day, ISAF issued a press release on the strike, as it normally did following operations of the secret task force:

Kabul, Afghanistan (Sept. 2) – Coalition forces conducted a precision air strike targeting an Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan senior member assessed to be the deputy shadow governor for Takhar province this morning.…

Intelligence tracked the insurgents traveling in a sedan on a series of remote roads in Rustaq district. After careful planning to ensure no civilians were present, coalition aircraft conducted a precision air strike on one sedan and later followed with direct fire from an aerial platform.

The strike was deemed important enough for the secretary of defense himself, Robert Gates, who happened to be visiting Kabul, to call attention to it at a press conference the next day: “I can confirm that a very senior official of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan was the target and was killed.… This is an individual who was responsible for organizing and orchestrating a number of attacks here in Kabul and in northern Afghanistan.”

But Mohammed Amin did not die that day. The real target had been the SIM card tracked so meticulously by “intelligence.” Very unfortunately, it did not belong to Amin but to the real-life Zabet Amanullah, a man the task force analysts had confidently assumed did not exist. He had indeed existed, as a quick phone call to any of a host of provincial or Kabul officials—or even a glance at a newspaper—would have made clear. He had been campaigning for his nephew, a candidate in the upcoming Afghan parliamentary election, and he had been on his way to a rally when he was killed. The ground around his burned and twisted vehicle was littered with election posters, with slogans such as “for a better future” still legible. The dead, campaign volunteers all, included five close relatives, among them his seventy-seven-year-old uncle.

Afghans, from President Karzai on down, were well aware of these obvious facts and said so. It made no difference. The spell cast by technical intelligence, with its magical tools of IMSI Catchers and cell-phone geolocation and social-network analysis algorithms and full-motion video, was too powerful for the truth to intrude, even after a dogged and resourceful investigator laid out the truth for all to see.

Kate Clark had none of the high-tech intelligence aids, but she knew more about Afghanistan than those who did. She had arrived in Kabul in 1999, when the country was still in the iron grip of the Taliban regime. She was the BBC correspondent, and the sole Western journalist in the country. Expelled in March 2001, she returned after the regime fell at the end of that year and continued reporting for the BBC until May 2010, when she joined the in-depth research group Afghanistan Analysts Network. Clark was perfectly aware that the high-tech assassins had murdered the wrong man, or rather men, because she had known Zabet Amanullah well. She had listened to the diminutive five-foot-two-inch Uzbek’s life story, which included fighting successively for the Soviet-backed Afghan regime, the anti-Soviet U.S.-backed Mujaheddin, and the Pakistani-backed Taliban prior to 2001. He also recounted his serial torture experience, first at the hands of the Soviets, then while imprisoned by the anti-Soviet and anti-Taliban commander Ahmed Shah Massoud (who kept him in a two-foot-by-two-foot-by-two-foot box for six months), and finally by ISI, the Pakistani intelligence service. These last, as he told Clark, were angry because he refused to join the reborn Taliban and go to fight the Americans. “They hung me from the ceiling by my wrists and by my ankles and beat me with chains.”

Finally released by the Pakistanis in 2008, Amanullah had fled to Kabul, where he supported himself by opening a pharmacy while anxiously soliciting character references and guarantees of protection from influential figures in the capital and his home province. In the maelstrom of modern Afghan politics, alliances and enmities are always fluid. The real-life ambiguities of the relationships and connections required for survival in such a society do not necessarily conform to the neat abstractions represented in the diagrams generated by social-network analysis. So when Amanullah decided in July to leave Kabul and go north to campaign for a nephew running for Parliament against a notorious Takhar strongman, one of the people he contacted was the influential Takhar Taliban official Mohammed Amin, whose calls were duly recorded and irretrievably entered into the system by Amin’s hunters.

Then came the inexplicable mix-up. Somehow, amid the swirling petabytes of America’s global surveillance system, the information identifying Amanullah’s SIM card, the IMSI number, was logged as belonging to Amin. From that point on, the task force had its unblinking eye on the former torture victim, nicknamed “Ant” for his short stature. Fixated on what their cell phone tracking equipment was telling them, they adopted the unshakable conviction that the Ant was in fact Amin, traveling under an alias. It was Amanullah whom they had followed north out of Kabul to Takhar, waiting and watching for the right time and place to attack. With eyes always on the telltale electronic signal, Amanullah’s exuberant election rallies, the fifty-car convoy of well-wishers that escorted him to his home village, his pictures in the newspapers, his radio interviews, his daily phone calls to district police chiefs informing them of his movements—all passed the high-tech analysts by. In a feat of surreal imagination, they did not question the unlikely proposition that an important figure in the Taliban would be traveling the countryside in a highly visible convoy or that the people who got out of the cars on that last trip through the mountains “apparently carrying weapons” might in fact be carrying cameras to photograph the scenery (as indeed they were). No one seemed to notice that the man holding the phone, killed with a carefully aimed bullet in the face from the helicopter, was actually calling the police. Their electronic data told them all they wanted to know.

Rapid and outraged Afghan protests that the strike had killed innocent civilians did little to shake military confidence that they had done the right thing. “We’re aware of the allegations that this strike caused civilian casualties, and we’ll do our best to get to the bottom of the accusations,” said Major General David Garza, deputy chief of staff for Joint Operations. “What I can say is these vehicles were nowhere near a populated area and we’re confident this strike hit only the targeted vehicle after days of tracking the occupants’ activity.” All of the dead, as far as the command staff were concerned, were ipso facto insurgents by virtue of their keeping company with Amin, whatever he was calling himself.

Just to be absolutely sure that Mohammed Amin had not somehow infiltrated the convoy, Kate Clark tracked down and interviewed each and every survivor of the attack, not only getting their stories but also checking on who had been sitting in each seat in the six cars. Looking through Amanullah’s passport, which he had left in his Kabul apartment, she saw that he had visited Delhi for a few days in late April 2010, at a time when intelligence had the Taliban leader Amin in Takhar, organizing attacks on Americans.

In December, Clark had a breakthrough. David Petraeus, the allied commander in Afghanistan who had made his name as the general that plucked victory from the jaws of defeat in Iraq, had always been assiduous in courting journalists, with great benefit to his public image. Impressed by Clark’s reputation as an acute and influential observer of Afghan affairs, the general invited her to dinner. Seizing the opportunity, she brought up the Amanullah case. Petraeus was unyielding in his stated conviction that they had got the right man. As he told a TV interviewer, “Well, we didn’t think. In this case, with respect, we knew. We had days and days of what’s called ‘the unblinking eye,’ confirmed by other forms of intelligence, that informed us that this—there’s no question about who this individual was.”

Confident of the story as well as his proven ability to charm the press, the general actually granted Clark rare access to the mysterious unit that had organized the killing. “He basically ordered the Special Forces to be frank with me, as he was so happy that they’d got the right person,” Clark told me later. Within a few days she was sitting with the notoriously unreachable Joint Special Operations Task Force as they revealed the process that had led them to target the convoy: the extraction of Amin’s phone number from the relative they had held in Bagram, the correlation with the SIM card, the tracking of the SIM north to Takhar in July, and their utter certainty that they had got the right man, even if he was calling himself by another name.

The experienced journalist was astounded at what she was hearing about the process that had led to the deliberate killing of ten people. The Special Forces refused to accept that they had mixed up two individuals, insisting that the technical evidence that they were one and the same person was “irrefutable.” They freely admitted that they had not bothered to research the biography of the man they thought they were killing. Amazingly, they claimed total ignorance of Zabet Amanullah’s existence. When she pointed out that Amanullah’s life and death were a matter of very public record, they argued that they were not tracking a name but “targeting the telephones.”

“I was incredulous,” she told me. “They actually conflated the identities of two people, and they didn’t do any background checks on either person. They had almost no knowledge about Amin, and they hadn’t bothered to get any knowledge about Amanullah. It’s quite shocking.” Despite all Clark told them, the Special Operations warriors’ faith in their technical intelligence remained unshaken.

The final nail in the coffin for the official story came six months after the attack. Michael Semple is an Irishman who has spent decades in Afghanistan getting to know the country intimately, speaks Dari (one of the principal languages), and, with his beard and habitual dress, can pass as an Afghan. As such, he has been able to forge contacts with many Taliban (getting himself expelled from Afghanistan by the Karzai government for his pains in 2008). In March 2011, six months after the death of Amanullah, Semple, after months of patient investigation, tracked down the real Mohammed Amin, very much alive and living in Pakistan. Amin readily confirmed many of the details unearthed by Clark, including his position as deputy shadow governor, the detention of a relative at Bagram, and the fact that Amanullah had been in telephone contact with him and other Taliban. In fact, according to Amin, the two men had spoken to each other on the phone just two days before Amanullah was killed. “There should not be any serious doubt about my identity,” Amin told Semple. “I am well known and my family is well known for its role in the jihad. Anyone who knows the personalities of the jihad in Takhar will know me and that I am alive.”

The meeting left Semple with the strong impression that it probably hadn’t been such a good idea to put Amin on the list in the first place, classifying him as a “gray area insurgent,” someone who was indeed fighting against the government and NATO but who was a “rational actor” with a plausible list of grievances who could potentially be reconciled to the Afghan government. “I did come to the conclusion that it had not been such a good idea to kill Amin and that he was much more useful alive than dead. Someone you could negotiate with,” Semple told me.

Being a Taliban “rational actor” in Afghanistan in 2010 was one quick way of climbing up the Joint Prioritized Effects List, which was numbered in order of priority. Meanwhile, despite what might seem to be Semple’s conclusive evidence that Mohammed Amin was alive and well, the military continued to insist they had “iron clad proof” that they had killed Amin but could not divulge what it was for fear of revealing “sensitive intelligence methods.” “On September 2, coalition forces did kill the targeted individual, Mohammed Amin, also known as Zabet Amanullah,” NATO spokesman Lieutenant Colonel John Dorrian told NPR in May 2011. “In this operation, multiple sources of intelligence confirm that coalition forces targeted the correct person.” Naturally, like any bureaucracy, the military is loath to admit mistakes, especially the secretive Joint Special Operations Command, with its useful cloak of mystery and omniscience.

However, it is quite possible that, beyond covering their collective behinds, the people who told Dorrian what to say and those who briefed Petraeus and Defense Secretary Gates did believe that all truth was contained in the plasma screens depicting that fatal SIM card’s movements. As we have seen, there is a recurrent pattern in which people become transfixed by what is on the screen, seeing what they want to see, especially when the screen—with a resolution equal to the legal definition of blindness for drivers—is representing people and events thousands of miles and several continents away. (It is not clear where, or in how many “nodes,” the analysis of Amin/Amanullah’s movements was made. It would certainly have been easier to ignore common sense if the fatal conclusions were being drawn at some distant point in the network.)

It had happened in Uruzgan in February 2010, when a Predator pilot in Nevada interpreted spots on a screen captured by an infrared camera fourteen thousand feet over Afghanistan as people praying, causing him to identify them as Taliban and therefore legitimate targets, while another, more open-minded observer, reviewing the same video concluded that the people in question “could just as easily be taking a piss.” Following Operation Anaconda, in February 2002, Special Operations commanders on an island off Oman, a thousand miles away from the battlefield, reviewed Predator video and thankfully concluded that one of their men that they had fought to rescue from an enemy-held mountaintop had died a heroic death, whereas in fact it was another American soldier, wounded and left for dead, who had fought on alone.

Some among the military are aware of the problem and strive to resist it. A-10 attack planes, for example, are, as noted, designed to afford the pilots the best possible direct view of the ground through their canopies. They do also carry video screens on their dashboards displaying infrared or daylight images from a camera-pod under the plane’s wing, but the pilots are trained to treat these as very much a secondary resource. “We call the screens ‘face magnets,’ Lieutenant Colonel Billy Smith, a veteran A-10 combat pilot, told me. “They tend to suck your face into the cockpit so you don’t pay attention to what’s going on outside.” Thus on May 26, 2012, a U.S. Air Force B-1 bomber, relying on a video image of the target (the weapons officer in a B-1 sits in an enclosed compartment with no view of the outside world), destroyed an Afghan farmer’s compound in Paktia Province in the belief that it contained hostile Taliban endangering U.S. forces. Minutes before, two A-10 pilots had refused orders to bomb the same target because they had scrutinized it closely with the aid of binoculars and concluded, correctly, that it contained only a farm couple and their children. Seven people, including a ten-month-old baby, died under the B-1’s multi-ton bomb load.

Neat computer-screen diagrams of Taliban or other insurgent networks based on the record of cell phone calls between their members can give a false impression of precision, making it all the easier to accept the impossible, such as the dual identity of Amin/Amanullah. The maze of ambiguous personal relationships based on shared histories, ancient enmities, and family and tribal ties in which Zabet Amanullah and Mohammed Amin moved would be impossible to reduce to a social-network chart, especially when based on imperfect intelligence. The imperfection was boosted by the policy of rounding up numbers of Afghans not because they were Taliban themselves but because they knew people who were. As Michael Semple remarked, many Afghans “have a few Taliban commander numbers saved in their mobile phone contacts” as a “survival mechanism.” These phone contacts would go into the social-network database but not necessarily with any indication of what their relationships actually were. So anyone with a lot of calls to numbers associated with people already on the JPEL in their phone record was at severe risk of going on the list themselves.

The whole complex effort was strongly reminiscent of the Operational Net Assessment approach to warfare promoted by the net-centric warriors in the 1990s, the notion that thanks to sensor, computer, and communications technology, all sources of intelligence and analysis could be usefully fused into a war-winning “shared knowledge of the adversary, the environment, and ourselves,” as an official manual put it. ONA was itself linked to the theories of effects-based operations (EBO), which, as we have seen, were defeated at the hands of Paul Van Riper in the Millennium Challenge war game. EBO had lost a little of its luster by the end of the decade, especially after General Mattis had banned the use of the term in his command in 2008. But the net-centric and target-list mind-set was very much alive, especially in the air force and in the rapidly expanding Special Operations Command. Stanley McChrystal himself, former chief of staff of Task Force 180, was fond of quoting (without attribution) the Rand pundit and netwar promoter John Arquilla’s aphorism “it takes a network to defeat a network.”

All of which leaves us with the question: What was the intended effect of the high-value-target kill/capture program in Afghanistan? Superficially, the object was straightforward and obvious: kill the enemy. Petraeus put it this way: “If you’re trying to take down an insurgency, you take away its safe havens; you take away its leaders.” In a slightly more detailed explanation, a lower-ranking official told me: “The intended effect was to disorganize the Taliban and put their leaders in fear, make them want to negotiate or surrender for fear of their lives. To put such a hurt on them that they would have to come to the negotiations table.” Marine Major General Richard Mills evoked a bucolic note, declaring in May 2011 that the aim was to make the Taliban “go back to their old way of life and put the rifle down and pick up a spade.”

The actual effects were certainly audible to anyone who heard Afghans expressing outrage at the violation of their homes by what some took to calling “the American Taliban,” especially when they arrested or killed civilians with no connection to the insurgents. In August 2008, the United States had obligingly bombed a family memorial service in Azizabad, a village near Herat, on the basis of a malign tip-off from a family enemy that this gathering was a major Taliban get-together. At least ninety people were killed, including sixty children. In an infamous February 2010 incident in Gardez, south of Kabul, a JSOC raid killed seven people, including three women, a district attorney, and a police commander. In an attempt to cover up the fiasco once they realized their error, the elite commandos used their knives to cut the bullets out of the women’s bodies and concocted a preposterous story about the women having been murdered by their own relatives in an “honor killing.”

In the Gardez case, as in Azizabad, the botched intelligence came not from esoteric telephone intercepts and social-network analysis but from some local rival of the murdered family. The May 2012 B-1 strike in Paktia Province that deftly obliterated a family of seven was reportedly also prompted by malign intelligence from a local source. “The bottom line is we have been played like pawns in a very deliberate power-grab scheme by mafia-like warlords,” an officer of great experience wrote me from Afghanistan in a bitter email in 2013 referencing such bloody mishaps. “It is like watching a gang war unfold between the Bloods, Crips, Hells Angels, Aryan Nation, etc.,… and we are prosecuting targets in support of all four gangs. Why? Because we like prosecuting targets as a military. It briefs well. And good briefs = good reputations = good career opportunities. Also, we like people who like us.”

Whether people were being killed as a result of these malign power plays or misplaced faith in technical intelligence, the United States paid a price with the civilian population. One measure of the cost to the overall U.S. war effort of the obsessive targeting of Taliban “leaders and facilitators” was unearthed by historian Gareth Porter, who noted a direct correlation between a stepped-up rate of raids in Kandahar Province in southern Afghanistan and the number of homemade roadside bombs reported by locals to the American forces. The turn-in rate had been averaging 3.5 percent between November 2009 and March 2010, according to the Joint IED Defeat Organization, which kept track of such matters. But as the Special Operations forces began their onslaught in Kandahar, the percentage of bombs voluntarily reported by locals fell like a stone to 1.5 percent and stayed at that level.

Clearly, the high-value targeting was counterproductive in terms of winning hearts and minds among the Afghan population, especially in view of the large number of innocents who were gunned down or blown apart. But the campaign did succeed in killing a large number of intended targets. Unfortunately these victims were less likely to be senior Taliban leaders, who for the most part survived in sheltered safety in Pakistan, unmolested by the CIA’s drone campaign, and much more likely to be lower-level provincial and district commanders. These were indeed slaughtered in large numbers, either by air strikes of the kind that dispatched Zabet Amanullah or by ground assaults by the Navy Special Warfare Development Group (DEVGRU), formerly Seal Team 6, and other Special Operations units. In a series of media interviews in August 2010, for example, Petraeus claimed that in almost 3,000 night raids over 90 days between May and July that year, no less than 365 “insurgent leaders” had been killed or captured, 1,355 Taliban “rank and file” fighters captured, and 1,031 killed. Leaving aside the number of innocent civilians represented in those figures (20 dead for every insurgent leader killed in July 2010, for example), there was clearly a high Taliban loss rate as a result of the escalating campaign. In the northern Afghanistan province of Kunduz, Task Force 373 began a sustained campaign against the Taliban in December 2009. Up until that point the enemy leadership there had been left entirely unmolested by SOF and had become used to the idea that they were invulnerable in their well-guarded compounds. But by the following fall, two successive generations of leaders had been eliminated, and the third was uneasily taking office. By October, seventeen commanders had been killed.

Special Operations had achieved similar results in Iraq, wiping out hundreds of insurgents thanks to McChrystal’s “industrial counterterrorism.” But, as we have seen, the effects of the operations were not necessarily as advertised. Rivolo’s analysis of 200 high-value-target eliminations had demonstrated that dead or captured Taliban commanders were quickly replaced, almost invariably by someone more aggressive. Just as in Iraq, the insurgency did not “fold in on itself,” despite claims to the contrary from U.S. headquarters. The presumed objective of the campaign was to make the Taliban less effective as a fighting force, but apart from occasional disruptions, there was little sign of this happening. Squadron Leader Keith Dear, a British military intelligence officer who later commanded the Operational Intelligence Support Group at NATO headquarters in Kabul, wrote in 2011: “the Taliban … today conduct attacks as complex, if not more so, than ever before, and continue to show the capability to coordinate and conduct attacks across a wide geographic area simultaneously.” Meanwhile, two years of the targeted-killing campaign had cost the Taliban in many parts of Afghanistan an entire generation of leaders. In many cases, the dead men were locally born and bred, and had ties to their communities; the new commanders, however, often tended to be outsiders appointed by the leadership in Pakistan. They were also younger: Task Force 373’s 2010 campaign in the north reduced the average age of commanders from thirty-five to twenty-five. A twelve-month onslaught in Helmand had similarly brought the average age down by May 2011 from thirty-five to twenty-three. “The Taliban leadership in 2011 is younger, more radical, more violent and less discriminate than in 2001, because of targeted killing,” Squadron Leader Dear bluntly concluded. “This new in-country leadership has increasingly adopted Al Qaeda’s terrorist tactics and have deeper links with Al Qaeda than their predecessors.”

It appeared that the equation Rivolo had discerned years before with regard to the narcotics business—that targeted killing had little effect on a leadership impervious to risk—still held true in Afghanistan, as it had in Iraq. The young fighters taking command were very unlikely to “pick up a spade.” Most of them had been fighting their entire adult lives. “This is Juma Khan, one of our distinguished commanders,” a Taliban commander named Khalid Amin, recently promoted from foot soldier following the deaths of two predecessors, explained as he guided a visiting film crew around a Taliban cemetery in Baghlan Province in 2011. “He was killed on the front line. This is Maulvi Jabar, our district chief. He was killed with 30 others in a night raid. When he died, the enemy said the Taliban was finished here. But three months later, our Islamic emirate is still strong. We have many more fighters than back then.… These night raids cannot annihilate us. We want to die anyway, so those destined for martyrdom will die in the raids and the rest will continue to fight without fear.”

“That’s why the Special Forces guys call it ‘mowing the grass,’” Matthew Hoh, who resigned his foreign-service position in Afghanistan in protest at the futility of the war, told me. “They know that the dead leaders will just be replaced.”

A marine officer who served two tours in the lethally dangerous neighborhood of Sangin, in northern Helmand Province, gave me a powerful analogy during a long discussion on the drawbacks of high-value targeting. “Insurgencies are like a starfish,” he said thoughtfully. “You cut off one of the legs of a starfish and within weeks it can regrow and become more resilient and be smarter about defending itself. I saw multiple Taliban commanders come in and out. The turnover rate was cyclic. So even if I kill one, it only took two weeks before the next guy came in. They didn’t miss a beat. You replace one guy, chances are the guy that’s coming in is more lethal, has less restraint and is more apt to make a name for himself and go above and beyond than if you had just left the first guy in there.

“The commander down here [Sangin] when I first got there had been around for years. He had become one of the water-walkers among the Taliban community, very popular amongst the people. We picked him off in an air strike with a group of ten on the other side of the Helmand River one day, standing around with their AK-47s planning their next operation. There was a good three-week period where nothing happened. It was eerie. But then we started to see some outside influence, maybe from Pakistan. The new commander was either taken from a different region and put in here, or a younger guy who was promoted and brought up to speed, he was more aggressive more radical, more ready to prove himself worthy. The amount of pressure plate IEDs [which go off when anyone steps on them] increased exponentially, to where little kids started to hit them. He wasn’t even letting the population know where they were, and while that was good for us because I could leverage the population that this young immature commander was more deadly to them than he was to me, it showed me that targeting these leaders made the problem ten times worse overall.”

My friend, a remarkable officer who actually managed to suppress the Taliban in his particular area by the end of his first tour in 2012, thought that making the enemy even more vicious and unpleasant than they already were was ultimately unproductive. But strange rumors, based on off-the-record conversations with military officers and Special Forces officers out in the field, were circulating that making the Taliban even more cruel might actually be official policy. If so, it certainly succeeded. By 2011 the Taliban were deploying eight-year-old children as involuntary suicide bombers, while in May 2014, a small group of young Taliban gunmen stormed a Kabul hotel and executed nine people in the restaurant. Three of the victims were children, including a two-year-old, shot in the face.

Among COIN (counterinsurgency) theoreticians, then ascendant in the U.S. Army, the rise of the young commanders was seen as a positive development. “That’s a win for us,” John Nagl, a former army officer and the coauthor of the U.S. Army’s counterinsurgency manual, told me. “We want to see younger commanders take over. They have less experience, they’re more inclined to mess up.” In fact, young men such as Khalid Amin, who had declared “we all want to die,” had a great deal of experience despite their tender years, having never known any life but war. Nor did it require a great deal of expertise to construct a $10 pressure-plate IED.

It is possible, however, that there was indeed an underlying Machiavellian element to the targeted-killing strategy: actually to encourage the already cruel Taliban to become even more vicious and barbaric. The rationale, so Special Operations officers would explain in discreet off-the-record conversations, was based on the success of the Iraq surge. The key development of that operation had been the pivot of the Sunni population, or at least their tribal leaders, from insurgency to support of the occupation forces, a development attributed to the adoption of COIN as a doctrine, not to mention the strategic genius of those who had introduced it. Hugely important in inducing the Sunnis’ change of heart, along with wads of cash handed to tribal leaders, had been their revulsion at the arrogance and cruelty of al-Qaeda in the areas where it had come to dominate, such as attempts in the al-Adhamiya district of Baghdad in 2006–2007 to force each family to give up a son as an al-Qaeda recruit or the shooting of barbers for giving un-Islamic haircuts, not to mention cutting off the fingers of smokers.

The triumph of the surge, which put a welcome gloss on the overall disaster of the invasion and occupation, was still very fresh in the minds of the U.S. national security establishment, particularly the army, when attention began shifting to Afghanistan in 2008. If the increased unpopularity of al-Qaeda had led to its defeat in Iraq, so, the thinking reportedly went, what was needed in Afghanistan was a really unpopular, “radicalized” Taliban, to be generated by killing off the (slightly) more moderate field commanders. Thereby afflicted, the population would, hopefully, rally to the Americans, or at least to the government of Hamid Karzai. In other words, eliminating Taliban leaders and other supposedly key individuals across the length and breadth of Afghanistan was not merely mindless slaughter but an effects-based operation.

Colonel Gian Gentile, the Iraq combat veteran and former West Point history professor known for his pungent critiques of COIN and its practitioners, thought that the scheme, of which he had no personal knowledge, sounded “like the typical pop sociological/anthropological nonsense and over thinking that many army officers have gotten themselves into. It also might indicate a rabid belief that the Iraq Surge could be made to work in Afghanistan along with its techniques and methods. “It just shows you,” he lamented to me in an email, “how far off the deep end the American army has gone.”

Dr. Peter Lavoy is one of the little-known but dependable officials who keep the wheels of the U.S. national security machine in motion. Deemed an expert in such recondite subjects as the use of biological and nuclear weapons and asymmetric warfare, he rose steadily through the ranks of intelligence and into the wider realm of policy making. By 2008 he was national intelligence officer for South Asia in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and as such was delegated to brief NATO allies on the U.S. intelligence assessment of the security situation in Afghanistan, which he described as “bleak,” according to the record of his November 25 address that year, classified “Secret” but subsequently released by Wikileaks.

The Taliban, said Lavoy, were making significant gains. Attacks were up 40 percent in a year, largely thanks to the failure of the Afghan government to deliver any services to the rural population while the Taliban were “mediating local disputes … offering the population at least an elementary level of access to justice.” In conclusion, he told the NATO meeting, “[T]he international community should put intense pressure on the Taliban in 2009 in order to bring out their more violent and ideologically radical tendencies (author’s emphasis). This will alienate the population and give us an opportunity to separate the Taliban from the population.”

Many greet the notion that U.S. policy makers and commanders would have been capable of thinking through second-order effects in this fashion with unbridled skepticism. Matthew Hoh, the state department official who gave up his career in protest of the Afghan war, told me that he had indeed heard about this plan but not until after targeted killing had the effect of radicalizing the Taliban. “I simply doubt our ability to be that prescient and competent,” he told me. “I haven’t seen it in other situations and I don’t see it here. I think this is, by and large, people and agencies trying to take credit for an unintended consequence.”

An officer serving in Afghanistan in 2014 had much the same reaction. “I don’t think that it was (or currently is) a ‘strategy’ across the board,” he wrote me. “I have yet to see one of those out here. No part of my ‘welcome aboard’ to Afghanistan included a history/analysis of the area … to include sources of instability and power players. At no time was I told ‘the strategy is to isolate X, while infiltrating Y and containing Z.’ Is that an effects-based strategy? Only if the effect you want is to generate chaos.”

But generating chaos can be a hard habit to break.