Chapter 10

Using acceptance and commitment therapy to empower the therapeutic relationship

Heather Pierson and Steven C. Hayes

Introduction

It is commonplace to emphasize the importance of the therapeutic relationship in clinical interventions. That connection is especially supported by a large body of mainly correlational evidence between outcomes and measures of the therapeutic alliance (Horvath, 2001) and a somewhat smaller body of evidence showing that relationship-focused treatment can be helpful (e.g., Kohlenberg, Kanter, Bolling, Parker, & Tsai, 2002). What is often not provided, however, is a workable model for how to empower the therapeutic relationship in therapy more generally.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT, said as a single word, not initials; Hayes, Wilson, & Strosahl, 1999) is a mindfulness, acceptance, and values-focused approach to clinical intervention. ACT, in a relatively short period of time, has shown a surprising breadth of impact, from diabetes management to coping with psychosis, from work stress to smoking (see Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis (2006) for a recent meta-analysis of ACT process and outcome data). We believe that this same model provides a clear guide for the development of more empowering therapeutic relationships.

In this chapter we will outline the ACT model of psychological flexibility and its basic foundations. We will show how the model seems to specify functional components of the therapeutic relationship that can be applied to the conduct of many types of therapy. This chapter will not go into great detail about how to establish these processes, since ACT has already been applied in controlled studies to both therapists and clients, and the technology for the two is quite similar. Book-length sources on ACT technology are readily available (e.g., Eifert & Forsyth, 2005; Hayes et al., 1999; Hayes & Strosahl, 2004).

Acceptance and commitment therapy

Intellectual context

ACT is part of the so-called third generation of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) interventions (Hayes, 2004). Along with therapies such as dialectical behavior therapy (Linehan, 1993), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2001), and functional analytic psychotherapy (Kohlenberg & Tsai, 1991), these technologies have created new alternatives within empirical clinical psychology. Third-generation CBT treatments tend to be contextual, experiential, repertoire building, and relevant to therapists themselves (Hayes, 2004). All of these features make these approaches ideally suited to empowering the therapeutic relationship.

In this section we will describe the underlying philosophy, basic theory, model of human suffering, and model of intervention that is in ACT. The reader will need to be patient, since it is only after all of this is described that we will be in a position to attempt to show that this model provides an innovative way of thinking about the therapeutic relationship itself.

Philosophy of science

ACT embraces a specific philosophy of science: functional contextualism (Hayes, 1993). Functional contextualism is a type of pragmatism. As with all forms of pragmatism, the “truth” of a theory is dependent on its ability to meet specified goals. Most of the features of contextualism can be derived from this approach to truth. For one thing, the whole must be assumed and the parts then derived for pragmatists. Differences among elements cannot be assumed. In psychology this holistic emphasis means that the historical and situational context of behavior cannot be fully separated from the behavior being analyzed. Another implication of a pragmatic truth criterion is that there can be different truths depending on one’s specific goals. Goals are what distinguish functional contextualism from more descriptive forms of contextualism such as dramaturgy, narrative psychology, hermeneutics, or constructivism. The goals of functional contextualism are prediction and influence, with precision, scope, and depth (Biglan & Hayes, 1996). Since the truth of a theory will thus be measured not only by how well it predicts events but also by how well it lends itself to changing those events, the analyses that result are necessarily contextually focused. This turns out to have positive benefits for the linkage between philosophy, basic science, and applied science since clinicians are inherently part of the context in which clients’ behavior occurs, and both prediction and influence are usually important to applied work.

Basic science

ACT is the only modern form of CBT with its own comprehensive experimental analysis of human language and cognition, relational frame theory (RFT; Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001). RFT takes the view that learning to form arbitrary relations between events is at the core of human verbal and cognitive behavior. There is a growing amount of supporting evidence for RFT, but it is beyond the scope of this chapter. For a more detailed review of the data on RFT, see Hayes et al. (2001).

For practical purposes, we can focus on four important findings in RFT research: human language and cognition are bidirectional, arbitrary, historical, and controlled by a functional context.

Bidirectionality means that the functions of language depend on a mutual relationship between symbols and events. This bidirectionality means that words can pull the functions of the events they are related to into the present. Normal adults can remember, predict, and compare things through the use of symbols, whether or not the events referred to are present. This allows verbal problem-solving but it also means that human beings are always only a cognitive instant away from pain – since through memory, prediction, or comparison humans have the capacity for psychological pain at any time and in any situation.

According to RFT, human language and cognition are in principle arbitrary – what we relate is not necessarily dictated by form. Kick a dog and he will yelp in pain – that reaction is dictated by form in that everything causing the pain is present in the dog’s current environment. Conversely, a person who has just had someone very near and dear die may cry when seeing a beautiful sunset, wishing the lost loved one could be here to see it. The crying is not dictated by form - even intense beauty can create sadness precisely because it is beautiful. This arbitrary quality of human language and cognition is both a blessing and a curse. A human child who learns that a dime is “bigger than” a nickel is on the way to being able to believe that, say, hard work is better than laziness. That same ability, however, will enable tears at sunsets or, say, thoughts that it would be better to be dead than alive.

RFT researchers have shown that these relational abilities are learned (e.g., Berens & Hayes, in press). They are historical. Behavioral principles themselves suggest that historical processes are not fully reversible (even extinction is a matter of inhibition, not elimination). As this applies to language it means that a person cannot fully get rid of anything in his history. For example, a person who, say, thinks “I’m bad” and then changes it to “I’m good” is not now a person who thinks “I’m good,” but a person who thinks “I’m bad. No, I’m good.” Where humans start from is never fully erased – because humans are historical creatures. Deliberate attempts to get rid of history and its echoes – the automatic thoughts and feelings that emerge from our past – often only amplify these processes. In part this is because it makes these events even more central. The same often holds true with emotions if they become verbally entangled. For example, a person who tries to get rid of anxiety because otherwise bad things will happen has now related anxiety to impending bad things. But anxiety is the natural response to bad things so this formulation will very likely increase anxiety. Deliberate control efforts focused on anxiety tend to evoke anxiety for this reason, defeating our purpose.

Fortunately, RFT shows a way out of this conundrum. The contextual events that cause us to relate one thing to another are different than the events that give these relations functional properties. Thus, according to RFT it is possible to change the functions of thoughts and feelings, even if their form or frequency does not change. So the person that thinks “I’m bad” may still have that thought as frequently as before, but the thought “I’m bad” will no longer lead to the same reactions. This is why it is not necessary from an ACT perspective to change the client’s thinking – what is more important is to change the behavioral functions of the client’s thinking. How this is done will become clearer later.

Model of human struggle

The model of psychopathology and human struggle offered by RFT can be summed up by the term psychological inflexibility, which has several interrelated components. The first component is cognitive fusion, which refers to verbal processes that excessively regulate behavior or regulate it in unhelpful ways due to the failure to notice the process of thinking over the products of thinking. Normal humans often become overly attached to a verbal formulation of events (i.e., rules) and as a result will fail to distinguish a verbally constructed world from the process of constructing it. This in turn will lead to a failure to contact the environment in flexible ways. For example, a person believing that she cannot attend social events because she will be anxious may avoid such settings, producing a more restricted life.

Cognitive fusion supports another component of psychological inflexibility, experiential avoidance, which is the attempt to change the form, frequency, or contextual sensitivity of private reactions even when doing so causes harm (Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette, & Strosahl, 1996). Experiential avoidance is particularly based on temporal and comparative relations – the relational ability to predict and evaluate emotions or thoughts as undesirable and then avoid them. Many “undesirable” emotions are natural reactions, based on the person’s history, to normal life events. When these reactions are avoided, their salience and importance is increased, which means that even situations that only brought up small levels of the undesirable reaction must now be avoided. This narrows the behaviors that a person can participate in if she is to effectively avoid those reactions. The social verbal community contributes to experiential avoidance by promoting a “feel good” culture in which undesirable emotions are supposed to be avoided and controlled.

Cognitive fusion also supports a loss of contact with the present moment and attachment to beliefs about one’s self, both of which further increase psychological inflexibility. The verbal construction of the self, the past, and the future gain more control over other behaviors, thus taking the person away from the consequences that are present in the current environment. For example, if a person is highly attached to his understanding of himself or the past (for example, as someone who has been deeply wronged), he may defend that conception with the cost of not engaging in behaviors that would move him toward valued ends (for example, spending so much time proving that the person wronged him that he does not spend time having meaningful interactions with others). As a result, values, or long-term desired ways of being, become less important (as measured by one’s overt behavior) than more immediate consequences such as being right, receiving approval from others, and feeling “good.” This lack of clarity regarding one’s values is another component of psychological inflexibility.

The ACT treatment model

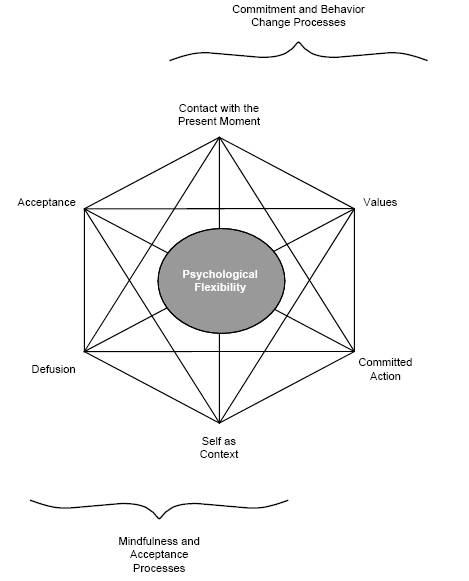

The six main components of ACT are inter-related and address the above problems by targeting psychological inflexibility. Figure 10.1 depicts the hexagonal ACT treatment model. Acceptance increases flexibility by bringing the individual into contact with previously avoided experiences in a safer context. Cognitive defusion decreases the behavioral regulatory effect of thoughts by increasing contact with the process of thinking instead of the products of thinking. For example, the thought “I’m worthless” is no longer seen as literally true, but instead is seen as simply a thought that is occurring in the present. This is similar to the cognitive therapy concept of distancing, but it is more radical, since it is applied in ACT to all thought, regardless of the strength of evidence for or against it. The point is not to note and correct unhealthy thoughts, but to change one’s relationship to thinking itself. Training in contact with the present moment increases and enriches the person’s awareness of external and internal events. Strengthening a transcendent sense of self (what is generally called self-as-context in ACT) decreases attachment to a conceptualized self, or one’s story about who one is. This sense of self is argued to be a consistent perspective or point of view from which experiences are reported verbally: namely, I, Here, Now. It is transcendent because its limits cannot be contacted consciously (one cannot consciously note when consciousness is not there). Becoming more aware of a transcendent sense of the self empowers acceptance and defusion as the person embraces experiences without excessively judging or evaluating, firm in that the content of experience is not psychologically threatening to this deepest sense of self. The self-as-context is usually experienced only in brief moments; however, those moments serve as examples of detachment from thoughts while still staying present with them. Values are chosen qualities of unfolding patterns of action. Values are continuously present from the moment they are chosen, but they are never obtained as concrete objects. For example, being loving is never finished, but once chosen is potentially continuously present as a value. The final component of ACT is committed action. Committed action means building larger and larger patterns of effective behavior, linked to chosen values. In all ACT protocols, a variety of behavior change procedures are included, often drawn from the behavior therapy literature.

Figure 10.1 The ACT model.

As is shown in Figure 10.1, the model can be chunked into acceptance and mindfulness components (acceptance, defusion, the present moment, and a transcendent sense of self ), and commitment and behavior change components (values, committed action, the present moment, and a transcendent sense of self ). These six processes together are argued to lead to psychological flexibility, which is the ability to contact the present moment fully as a conscious person (as it is and not as what it says it is), and based on what the situation affords, to persist or change behavior in the service of chosen values.

ACT thus can be simply defined as an approach that uses acceptance and mindfulness processes, and commitment and behavior change processes, to produce psychological flexibility. ACT contains myriad techniques focused on each of its component areas, but it is the model, not the technology, that most defines ACT. Any protocol that accords with the model can be called ACT, whether or not the techniques have been generated by ACT researchers and clinicians.

Brief overview of ACT data

ACT has a growing amount of empirical support with a variety of populations, including depression (Zettle & Hayes, 1986; Zettle & Raines, 1989), worksite stress (Bond & Bunce, 2000), psychosis (Bach & Hayes, 2002; Gaudiano & Herbert, 2005), social phobia (Block, 2002), substance abuse (Hayes et al., 2004b), smoking (Gifford et al., 2004), diabetes management (Gregg, 2004), epilepsy (Lundgren & Dahl, 2005), chronic pain (McCracken, Vowles, & Eccleston, 2005), and borderline personality disorder (Gratz & Gunderson, 2006), among other problems. Some of the studies above include active therapeutic comparisons, as where others are compared to inert control conditions. A recent meta-analysis found large effect sizes for ACT as compared to wait lists or placebos, and medium effect sizes as compared to existing treatments (Hayes et al., 2006); several studies showed good mediational effects for processes specified by the ACT model.

The therapeutic relationship from an ACT model

Thus far we have spent time laying out the underpinnings of an ACT model, and some of the evidence in support of it, so that we can be in a position to examine the therapeutic relationship from this point of view. In summary, an ACT model claims that psychological inflexibility makes it difficult for human beings to learn effectively from experience and to take advantage of opportunities afforded by situations. It is proposed that psychological inflexibility emerges in part from the over-reaching and poorly targeted effects of human language that creates excessive, restrictive, and improperly targeted forms of rule-following and high levels of experiential avoidance. Greater psychological flexibility and effectiveness is said to result from reining in these repertoire-narrowing processes and instead engaging in committed action linked to chosen values.

As a shorthand you can distill this model into seven words: acceptance, defusion, self, now, values, commitment, and flexibility. Although it can readily be applied to psychopathology, the model is not one of abnormal behavior per se but of human effectiveness and ineffectiveness. Given that expansive purpose, if this model is correct, it should provide guidance for the establishment of powerful therapeutic relationships. Note that we are not just speaking here of the therapeutic relationship in ACT as a treatment modality. Rather, to the extent that the model focuses on key processes, an ACT approach to therapeutic relationships should be able to be applied to more forms of therapy, provided there is not a fundamental conflict between the models. For that reason, in this section of the chapter we will not attempt to link this analysis to specific ACT techniques or components of therapy. When applied in ACT, however, all of the elements do come together in a unique way, as we will discuss later.

The seven-element ACT model we have described can be applied to the therapeutic relationship at three levels. The first level is the psychological stance of the therapist with regard to his or her own psychological events that is then brought into the moment-to-moment interaction of the therapist and client. In addition to their technical skills, therapists need to have personal psychological skills that they bring into the therapeutic relationship. The ACT model specifies those psychological skills: acceptance, defusion, self, now, values, commitment, and flexibility.

The second level is the level of therapeutic process. By that we mean the qualities of therapeutic interactions. The ACT model suggests qualities that are empowering, whether or not ACT is the treatment modality. These qualities are also acceptance, defusion, self, now, values, commitment, and flexibility.

The final level involves the client’s psychological processes that are targeted. This is the usual domain of therapeutic writing, and has been an extensive focus of ACT books and articles. These targets are part of the therapeutic relationship in the same way that such skills on the part of the therapist enter into the therapeutic relationship.

In other words, we are arguing that the ACT model itself is a model of a powerful therapeutic relationship, when examined at the level of the therapist, therapeutic process, and the client. In the following sections we will consider each of the core ACT elements and consider at each of these three levels whether they are a necessary or at least a very helpful psychological aspect of powerful and effective therapeutic relationships.

Acceptance

ACT targets experiential avoidance: the attempt to escape or avoid the form, frequency, or situational sensitivity of private events, even when doing so creates psychological harm. The alternative skill that is taught is acceptance: making undefended contact with such events in the service of chosen values. This domain is relevant to the therapeutic relationship at all three levels we have described: the therapist, therapy processes, and client psychological targets.

Therapist

Experiential avoidance on the part of the therapist is a potent barrier to an open, effective, and empowering relationship. An avoidant therapist may fail to explore certain client topics if they touch on personally difficult material, or may change the topic when they emerge, or even fail to acknowledge their presence at all. For example, a therapist who avoids feelings of anger may not recognize a client’s anger, may fail to follow up on it when it emerges in session, or may fail to ask about it and its roots when anger outside of session is described. An emotionally avoidant therapist may fail to notice his or her own feelings that emerge in session, thus losing one of the most important sources of clinical information about subtle events occurring in the moment. An avoidant therapist may fail to see what a client is thinking if those thoughts are disturbing, reducing the richness of understanding that is critical to clinical work.

The therapeutic relationship that is established by an experientially avoidant therapist can take on a fake or manipulative quality for no other reason than that the therapist is avoidant. There is a reason for this: avoidance itself is fake and manipulative. The fact that it is self-fakery and self-manipulation does not alter that fundamental truth. For example, suppose a therapist is unsure what to do in session and does not feel confident. The experientially avoidant therapist might attempt to escape from these feelings by a show of bravado and certainty, or may withdraw into fear-based inactivity disguised as a therapeutic style, such as validation or Rogerian reflective listening. Either of these reactions, as a method of avoidance, is designed to be a false communication. A therapist making a display of bravado and certainty in response to a lack of certainty, for example, is attempting to fool and bully the client into thinking that he or she is confident and sure-footed. Even if the client does not overtly detect the deception, few will fail to notice that the relationship seems disconnected rather than engaged. Meanwhile, the therapist will have a hard time fully focusing on the client while simultaneously attempting to play a role to cover up the true state of affairs. Verbal content, verbal tone, and even facial expressions will need to be carefully monitored, which will quickly reduce the capacity to attend to the client or even to remember what was said (Richards & Gross, in press).

Experiential avoidance need not be based on content-specific therapist issues to be harmful. Fairly generic reasons will do. For example, suppose a clinician has a difficult time seeing another human being in pain, as most humans do. If that feeling cannot be embraced, the clinician has a wide variety of unhealthy steps to take to reduce the pain. The clinician can reassure the client whether or not that is clinically called for, ignore asking more about the client’s pain when it appears, or communicate the message that the client should say things are fine even if they are not. In so doing, the focus shifts from dealing effectively with the client’s reality to the need for manipulating the therapist’s reactions, and an opportunity for clinical progress is squandered.

Conversely, if a clinician has good acceptance skills and is willing to use them in session, a much broader range of flexible alternatives is clinically available. The issue shifts from tracking and avoiding what pushes the therapist’s buttons to tracking and approaching what is helpful to the client. Issues the client is dealing with can be more readily allowed into therapy, and the therapist has a richer set of private reactions available to provide subtle information about such issues as the impact the client may be having on others outside of therapy, the current psychological state of the client, or the functional classes that lurk below the readily accessible topographical features of client statements or behavioral reactions.

Quite apart from the utility of acceptance-based clinical work, the secondary impact of therapists’ avoidance can be large. When the client senses these avoidant processes, the client may believe that she is inherently unacceptable or loathsome, so much so that even a therapist cannot look unblinkingly at her situation. The client may begin to worry more about protecting the therapist than about therapeutic progress, and may put on a show to rescue the therapist from discomfort. Seeing experiential avoidance being modeled, the client may attempt to adopt this approach and apply it to her own problems. The client may subtly be shaped into avoiding certain clinically important content areas, without even being aware of that process, thus reducing contact with needed information.

In a broader sense, avoidant relationships are inherently invalidating. Part of this sense of invalidation comes because such relationships are not genuine. The client will sense that something else is in the room, but will not know what it is, or even that it is an issue with the therapist and not themselves. In order to stay avoidant the therapist may fail to notice what is actually occurring or may be unwilling to acknowledge it once seen, which makes a sense of the lack of genuineness difficult to describe and correct. The client is put in a “crazy-making” situation, but may be unable to detect where the source of the problem lies, and due to the power differential in therapy, may be particularly unlikely to see the true source of the difficulties.

Process

An eyes-closed exercise commonly done in ACT workshops consists of a process in which individuals return in imagination to their childhood homes. At one point late in the exercise they are asked to be the adult they are now and to meet the child they were then. They are asked to look into the eyes of that child and see what it was that was most wanted. Many answers come up, some of which (e.g., “safety”) are extremely poignant, but the most common answer is some form of “love and acceptance.”

Humans carry a deep need for acceptance in social relationships. Acceptance does not mean approval. It means looking, seeing, acknowledging, feeling, and thinking. It means being willing to see the client’s world from within, without letting judgments and evaluations overwhelm that process.

Concretely, acceptance involves taking in what the client is saying and doing; exploring these events fully when clinically relevant; being fully open to the client’s history and the feelings and thoughts it produces; and standing with the wholeness and consciousness of the person. Acceptance does not mean approval or compliance, and it does not mean that change is irrelevant. Especially in domains that can be changed readily, such as overt behavior, or dangerous situations, change is often targeted in ACT. But the therapist is open to all thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and memories expressed by the client as valid experiences in and of themselves. They do not necessarily mean what they “say they mean” by their form. Furthermore, the reverse is also true – the therapist is willing to express thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and memories when it is appropriate and models acceptance of these events, while simultaneously engaging in valued actions.

Client

When a client is being avoidant in session, it can be manifested in several ways. The client may change the subject when a certain topic comes up, become disengaged or stop interacting with the therapist, become defensive and/or aggressive toward the therapist if a topic is pursued, or may “play along” even though not emotionally contacting the material. All of these reactions can interfere with the therapeutic relationship, especially if the therapist responds in avoidant or cognitively fused ways, such as pretending that nothing is happening or working frantically as if the responsibility for change is entirely with the therapist. Conversely, as the client becomes more accepting, the client is better able to bring difficult private events into the present moment. The positive impact of the acceptance abilities of the therapist and the acceptance process in the treatment sessions is amplified as the client is better able to express difficult psychological material and stay in contact with these events during sessions.

The impact on qualities of a therapeutic relationship

It is not by accident that clients will say that what they most needed as children was “love and acceptance.” Acceptance is a kind of love – the “agape” kind, brought into a specific moment. In that sense, from an ACT point of view the core of a powerful therapeutic relationship is a loving relationship.

Defusion

Language is a tool. It has evolved because of its utility to human beings. But part of the illusion of language is that symbolic events are what they say they are regardless of whether they are useful. This is the core process underlying cognitive fusion. For example, if a therapist thinks “I am bad,” the “truth value” of that statement is seemingly to be found in determining whether or not it corresponds with the therapist’s competence level. If it corresponds, it is “true,” whether or not it is useful.

From an ACT perspective, conversely, effective action is truth. Workability is the truth criterion. It is not possible to treat language that way, however, if languaging is allowed to go on entirely in a normal context. The normal context must itself be changed.

In a normal context (a context of literal meaning, reason-giving, prediction, evaluation, and so on) words mean what they say they mean. If a person thinks “I’m bad,” it is as if their own badness has somehow been contacted or discovered and then simply described. Said more simply, it is as if the “badness” is in the event (in this case, the person). But evaluations are not primary properties of events – they are in the interaction between the evaluator and the evaluated. Awkward though it is, to be more technically correct about what is happening one would have to say “Right now I’m badding about me,” instead of “I’m bad.” No one would adopt such an awkward way of speaking for very long, and even if they did the illusion of language would still be a threat, because now this new way of speaking could be taken literally. It is the essence of this posture (a detachment from literal language), which we call defusion, that is the goal – precisely so that workability may now move to center stage as a truth criterion. Defusion is the process of altering the automatic behavior regulatory effects of language by noticing the ongoing process of relating events. If the verbal formulation is helpful, it can still be followed. If no behavior change is called for, the person may simply notice what came up. Defusion allows for more behavioral flexibility: one can take what is useful about thoughts and judgments without being compelled to follow verbal rules that may arise if it does not work to do so.

Therapist

Defusion is a powerful ally to the development of a therapeutic relationship, and fusion is a powerful block to that process. When a therapist has become fused with thoughts in session, the behavioral options immediately narrow because only behavioral options that are implied by the adopted verbal formulation are now “logical” or “sensible.”

Fusion can come in many forms. The therapist may become fused with the client’s stories and support them even if that is unhelpful. This superficially can feel validating (“you poor dear – it is awful to be victimized like that”) but it does not have the desired effects of true validation. The client will usually feel supported, but with a sense of righteous entanglement, not a sense of liberation. The creativity possible in a more genuine relationship is diminished since the client intuitively knows that these stories and reasons are old, predictable, and well-explored.

The therapist can become fused with judgments and interpretations about the client, rather than allowing them to be one of many possibilities. It can then become important to be right about these judgments and interpretations, and the client begins to feel as though he is not known but is merely a kind of pawn in a cognitive game being played by the therapist. As fusion takes hold, the therapist may find herself arguing with the client or trying to convince the client of something, which will immediately undermine the therapeutic relationship.

In one of the more destructive forms of fusion, the therapist can become fused with self-focused thoughts. As worries and self-evaluations come up, if they are taken literally the client in essence disappears while the therapist becomes absorbed into a booming monody heard by an audience of one.

Defusion allows a different, more flexible dance on the part of the therapist. All thoughts are eligible to be noticed and considered, from random associations to full-blown formulations. There is nothing to be right about in any of this – rather, thoughts are viewed only as tools for making a difference. Because there is nothing to be right about there is nothing to defend – all formulations are held lightly, not because there is not enough evidence or because they might be wrong. They are held lightly because language itself works better when held lightly: by so doing, one can have the benefits of verbal rules without their costs in the form of psychological rigidity.

Process

By adopting a defused approach, the therapist immediately leaves the mountaintop of defended expertise for a more equal, horizontal, and vulnerable position in the relationship. Every statement, whether by the therapist or by the client, is a possibility that points to opportunities for action, not a dungeon of rightness and wrongness. Differences, and inconsistencies – between and within each party of the relationship – can be noticed without fear, opening up new territory to explore. If an accepting relationship is loving, a defused relationship is playful, flexible, and creative.

When therapeutic interactions are defused they can produce a sense of ambiguity or confusion, almost by definition, but they also lead to a sense of openness, creativity, and genuine interest in the moment that empowers the therapeutic relationship. The benefits are much more easily accomplished as fusion and acceptance are successfully targeted in the client, since the sense of ambiguity or confusion can be a source of struggle on the part of the client when these skills are absent. For that reason, the degree to which the interactions in therapy are obviously defused needs to be titrated to fit the client and the client’s current acceptance and mindfulness skills. A little overt defusion can go a long way. Further, some forms of therapy push for much less defused forms of interaction as a matter of technique – cognitive disputation or examining the evidence in support of a thought, for example – and these can be difficult to integrate with a defused approach if they become too dominant clinically.

Client

If the therapist adopts a defused stance, and brings it into the therapy interaction, the client’s level of fusion will necessarily be targeted. Fusion emerges from a social/verbal context, and it “takes two to tango.” Modeling defusion can help the client see the effects of defusing from thoughts in vivo, which may make it more likely that the client will be able to implement it into practice.

When a client is fused with certain content, that attachment will be manifested in his reluctance to consider alternative possibilities, his resistance to letting go of certain explanations, and/or a high level of believability in certain thoughts. The client may become argumentative and defensive or otherwise resistant to suggestions. He may argue specifically that something does not fit in with his self-conceptualization and express that he feels invalidated. Usually the story people have of themselves is too narrow and leaves out other aspects that also make up who they are. Psychological inflexibility is the handmaiden of cognitive fusion. The objective when using the ACT model is to move away from right and wrong and literal truth or falsity, to workability.

The impact on qualities of a therapeutic relationship

When a defused stance is adopted, the therapeutic relationship becomes more playful, creative, and effective. It feels collaborative, horizontal, and connected. Language is now no longer a trap – it is grist for a process of empowerment.

A transcendent sense of self

Attachment to the conceptualized self is a type of fusion that deals with the story of who one is, and thus fusion is an enemy to transcendence. Contact with a transcendent sense of self involves looking at external and internal events from a consistent perspective or point of view, often referred to as the “observer self.” We are not speaking of a literal point of view but of a locus or a context: I/Here/Now.

Language enables self-awareness: it enables one to see that one sees. But certain aspects of language enable one to see that one sees from a perspective. One sees from here; one sees now; and that is very much what ones means when one says, “I see.”

This insight was a starting point for both ACT and RFT. In an article entitled “Making sense of spirituality” (Hayes, 1984) it was argued that a transcendent sense of self was a side-effect of what we now call deictic relations, such as I/You, Here/There, and Now/Then. Deictic relations must be taught by demonstration (thus the name, which means “by demonstration”) since they are with reference to a point of view. Unlike, say, big and little, here and there have no formal referent. What is “here” to me is “there” to you. As a side-effect of such training a consistent “locus” is produced, which is at the core of a transcendent sense of self.

Seeing from a perspective is inherently transcendent and spiritual for reasons laid out in that article: once a sense of perspective arises it is not possible to be fully conscious without it. You cannot know, consciously, the temporal or spatial limits of “I” in the sense of “I/Here/Now.” But the only events without temporal or spatial limits are everything and nothing - the very label Eastern thinkers apply to the spiritual dimension. What is “spiritual” is not thing-like – as we say, not material (the very word “material” means “the stuff of which things are made”).

While this started as a theoretical idea more than 20 years ago (Hayes, 1984), we now know that deictic relations are indeed central to perspective-taking skills, and that they can be trained in children who do not have them (Barnes-Holmes, McHugh, and Barnes-Holmes, 2004; McHugh, Barnes-Holmes, & Barnes-Holmes, 2004). There is a deep philosophical meaning in the data coming from the RFT labs. Like all relational frames, deictic frames are mutual and bi-directional. And it is here that the deep philosophical meaning arises: one cannot learn “I” in a deictic frame sense of the term except by also learning “you.” The same applied to Here and There, or Now and Then. Said in another way, I do not get to show up as a conscious human being except in the context of you showing up in that same way. If I cannot begin to see the world through your eyes, I cannot see the world through my eyes. Said in another way, consciousness and empathy are two aspects of the same process. For that reason, contact with a transcendent sense of self supports a particular kind of relating, as we will show.

Therapist

A strong transcendent sense of self, and loosened connection to a conceptualized self, is a powerful skill for therapists. The negative effects of a strong attachment to a conceptualized self can be seen in session. For example, if a therapist is attached to seeing herself as a competent and confident individual, she may avoid trying new things because she feels less confident about her abilities in that area.

Connecting with a sense of self-as-context greatly reduces this process. In a deep and entirely positive sense of the term, “I” am nothing (in the sense of not being a thing – indeed, nothing was originally written “no thing”). There is no need to defend nothing or to be right about nothing – and thus a transcendent sense of self supports acceptance and defusion. It also supports connection, since the no-thing that is “I/Here/Now” for me is in some important way indistinguishable from the no-thing that is “I/ Here/Now” for you. Said in another way, at a deep level human consciousness itself is one. There can be no greater sense of sharing and connection than that.

Process

When this sense of oneness and transcendence is part of the therapy process, the work is compassionate and conscious, with a sense of a calmness, humility, and sobriety. It is “in the room” that the therapist and client are more than their roles, and more alike than different. Neither the client nor the therapist is an object – they are conscious human beings mindfully attending to the reality of living.

This sense is profoundly beneficial to the therapeutic relationship. The therapist can more easily be mindful of reactions as information about what is happening in session. Because the client’s behavior in session is likely similar to her behavior in other situations in her life, the therapist who is watching her reactions without attachment to them is in a better position to help the client with problematic interpersonal behavior. When the therapist is willing to let go of her attachment to her conceptualized self, she both models self-acceptance for the client and is more able to accept the client and her struggles.

Client

Helping a client contact their own spirituality provides a sense of peace, wholeness, and inherent adequacy. It greatly empowers acceptance and defusion, amplifying the work done in other areas.

The impact on qualities of a therapeutic relationship

This quality of a therapeutic relationship from an ACT point of view linked to a sense of transcendence is connected, conscious, and spiritual.

Contact with the present moment

When the conceptualization of the past and/or the fear of the future dominate the client’s or the therapist’s attention, it leads to a loss of contact with the present moment. When the client is not in the present moment, he may be actively struggling, daydreaming, or otherwise not engaged with the therapist. This is problematic because life only happens in the present moment. This is true as well of the therapeutic relationship. They are not fully connected to each other and therefore, not fully connected to the work being done.

Therapist

When the therapist is focused on the past or future, it is easy to miss both the connection with the client and certain functions that the client’s insession behaviors are serving. Ways that the therapist can be pulled away from contact with the present moment include thinking about what to do next in session, thinking about what has already happened, or evaluating her performance. Being able to come back to the present grounds clinical work in the moment-to-moment reality of a therapist and a client working together. Now.

Process

When sessions get “mindy” they lose their punch. This can occur if either party to the therapeutic interaction psychologically drifts away to other times and places. Usually simply acknowledging that fact (which is, after all, itself occurring in the present moment) can shift the process in a healthy direction. Consciously saying or doing things that are present-focused, such as taking a deep breath together with the client, or taking a moment to notice (in the present moment) that they are two human beings that have come together for a single purpose, can situate therapy work in the here and now.

It is often necessary to do work in session that is about other times and places. Clients are asked about their lives; problems about to be faced are addressed. But even as that work is being done, it is being done here and now, between two people. Noticing that situates such work in the present even if it is “about” the past.

Often, however, the real work can be done by focusing on the present therapy process. There is no need to talk about experiential avoidance or cognitive fusion, for example, when it is usually quite easy to find it then and there . . . in the room . . . in the relationship.

Clients are sometimes disconcerted by this approach. A person struggling with anxiety will not necessarily see the immediate relevance of working on, say, the discomfort of being known in therapy. But from a behavioral perspective larger functional classes are better targeted when they are targeted in a number of ways. It promotes healthy forms of generalization, for example, for an anxiety disordered client to see that experiential avoidance is not merely a matter of avoiding panic attacks. By dancing back and forth between processes occurring in the moment and functionally similar processes occurring in other settings, the present can become a kind of tangible laboratory to unravel functional patterns and to learn new ones, while also making obvious to the client that this is highly relevant to other times and places.

Client

Life goes on now, not then. And life is about many things, not just a few. The repertoire-narrowing effects of fusion and avoidance are resisted by the repertoire-broadening effects of what is afforded by the here and now.

The impact on qualities of a therapeutic relationship

This applies to the therapeutic relationship especially. Building the skills to contact the present moment automatically strengthens the possibility of a more powerful therapeutic relationship for that reason. A powerful therapeutic relationship is alive, vital, and in the present.

Values

The pain of psychopathology has two sources. The smaller source is the one usually focused on: the pain of struggling with symptoms. The larger source is often not mentioned: the pain of a life not being lived. Values are choices of desired life directions. Values are a way of speaking about where to go from a life not being lived. They are what therapy is really about – or should be.

Therapist

What is being a therapist really about? There are no set answers to this question – each therapist can generate their own. What is important about ACT as it applies to the therapeutic relationship is that it asks this question, and invites the therapist to place the answer into the heart and soul of their clinical work. Most of the barriers to an intense therapeutic relationship are orthogonal or contradictory to therapists’ values. Their own psychology may push therapists to want to look good, be confident, be right, not be hurt, be the expert, avoid guilt, make a lot of money, and so on, but it is rare that any of these are chosen values. Therapists usually value such things as wanting to serve others, to alleviate suffering, to be genuine, and to make a difference. All of these values can empower a genuine therapeutic relationship and can help therapists be mindful of the cost that can come from putting on a therapeutic clown suit and acting out their role.

Process

Values work enables the therapeutic relationship to be grounded in what the therapist and client most care about. Each and every moment in therapy should be able to be linked to these values, from the simplest question to the most demanding homework exercises. If the client and therapist are clear about what is at stake, the mundane is vitalized, the painful is dignified, and the confrontational is made coherent. The qualities of therapy are about something, and they are about what the client most deeply desires.

Client

Helping clients to realize what they really want as qualities of life and distinguishing this from specific, concrete goals along that path, serves as a profound motivator for taking needed but difficult steps in life. That includes the steps that lead to a meaningful relationship. It is values that make all of the other elements in the ACT model make sense. Acceptance, defusion, and the like are not ends in themselves – they are means to living a more vital and values-based life. Thus, client work on values is directly supportive of the application of the entire model we have presented to the therapeutic relationship.

The impact on qualities of a therapeutic relationship

Thus, the purpose of a therapeutic relationship is not just a concrete goal, but a direction or quality of living. In a sense, if a therapeutic relationship is values-based, the process is the outcome. A therapist doing what there is to be done in the service of the client is modeling an approach to others and to life, one that is dignified by human purpose.

Committed action

The bottom line in therapy is what we do; what the client does. Committed action is about overt behavior change. While working on committed action (when behavior change is actually taking place) all the other components (acceptance, defusion, values, etc.) are revisited because people become restuck. All the other ACT processes are in the service of this behavior change or change in ways of living.

The therapeutic relationship fosters committed action in that it provides an accepting, open, creative environment for trying new ways of living. When the client and therapist are working on committed action, the relationship is enhanced through their common purpose.

Therapist

A therapist living out a valued life in their work is much more powerful in that she is more active, vitalized, and less prone to burnout. It is through the therapist’s committed actions that all the other parts of ACT are carried out. From this place the therapist can do what needs to be done to be effective with her clients.

Process

Work on committed action includes finding barriers to the client’s moving forward in a personally meaningful life. This process unites the client and therapist in a common purpose. The therapist can be supportive and instructive in the accepting, open, and creative relationship that has already been established through the other ACT processes.

Client

Committed action is about actually living out one’s values, or said another way building larger patterns of behavior that work toward valued living. Often clients become stuck again in old patterns. Working with the therapist to identify these barriers and find new ways to act in these situations supports both the client’s life and the therapeutic relationship.

The impact on qualities of a therapeutic relationship

Thus, a therapeutic relationship is active and action focused. It is not just about living – it is living.

A psychologically flexible relationship

Putting these all together, an empowering therapeutic relationship, from an ACT perspective, is an accepting, loving, compassionate, mindful, and creative relationship between two conscious and transcendent human beings, who are working together to foster more committed and creative ways of moving toward valued ends. It avoids unnecessary hierarchy and gravitates toward humility over pretense; effectiveness over self-righteousness. Said more simply, powerful therapeutic relationships are psychologically flexible as ACT defines the term.

How is this different than the therapeutic relationship from any other perspective? It is different in several ways: it is not merely a matter of being supportive, or positive, or empathetic – it is a matter of being present, open, and effective. Some parts of this model may be difficult. Applying the model requires substantial psychological work on the part of the therapist – it is not a mere matter of therapy technique. To the extent that the model is correct there is no fundamental distinction between the therapist and the client at the level of the processes that need to be learned. The targets and processes relevant for the client are those relevant to the therapist and those relevant to the relationship between them. This suggests that it should be possible to use ACT with therapists, and indeed ACT is one of the few psychotherapies that is vigorously exploring that very idea in research.

In one recent randomized study (Hayes et al., 2004a), ACT was shown to reduce therapists’ entanglement with negative thoughts about their most difficult clients, and that in turn considerably reduced their sense of job burnout. While the impact on the therapeutic alliance was not assessed, it seems quite likely that entanglement with negative thoughts about clients would be harmful.

Several other such studies have been conducted but not yet published. So far we have found that ACT helps therapists learn other new clinical procedures, to produce good outcomes even when they are not feeling confident, and to reduce the believability and impact of thoughts about barriers to using empirically supported treatments.

ACT training usually focuses not just on technique but also on the therapist, and on processes of change. Thus, the research finding that training in ACT makes generally more effective clinicians (Strosahl, Hayes, Bergan, & Romano, 1998) may in part be because training in ACT includes applying an ACT model to the therapist.

While it is early, it appears as though an ACT model does describe processes of relevance to therapists and their relationships with clients. Explicit tests of this idea will await future research, but, as the present chapter shows, the model readily leads to several ideas about how to create curative relationships.

Conclusion

It not uncommon for cognitive behavior therapists to underline the importance of the therapeutic relationship, but in general these efforts have been technological. The therapeutic relationship is a powerful engine of change, and deeply connected relationships empower clinical work of all kinds, but this chapter has attempted to go one step beyond that agreedupon point. We are arguing that ACT contains within it a model of an empowering therapeutic relationship itself: what it is, why it works, and how to create it. In so doing, a circle is closed that draws the client and therapist into one coherent system. Therapist and client are both in the circle, and for a very basic reason. They are both human beings, each struggling with their own experiences, and yet bound together to accomplish a common purpose that each one values. In this view, therapist, client, and process are all part of one common set of issues that originates from the human condition itself.

References

Bach, P. & Hayes, S.C. (2002). The use of acceptance and commitment therapy to prevent the rehospitalization of psychotic patients: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1129–1139.

Barnes-Holmes, Y., McHugh, L. & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2004). Perspective-taking and Theory of Mind: A relational frame account. The Behavior Analyst Today, 5, 15–25.

Berens, N.M. & Hayes, S.C. (in press). Arbitrarily applicable comparative relations: Experimental evidence for a relational operant. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis.

Biglan, A. & Hayes, S.C. (1996). Should the behavioral sciences become more pragmatic? The case for functional contextualism in research on human behavior. Applied and Preventive Psychology: Current Scientific Perspectives, 5, 47–57.

Block, J.A. (2002). Acceptance or change of private experiences: A comparative analysis in college students with public speaking anxiety. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, State University of New York, Albany.

Bond, F.W. & Bunce, D. (2000). Mediators of change in emotion-focused and problem-focused worksite stress management interventions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 156–163.

Eifert, G. & Forsyth, J. (2005). Acceptance and commitment therapy for anxiety disorders. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Gaudiano, B.A. & Herbert, J.D. (2005). Acute treatment of inpatients with psychotic symptoms using acceptance and commitment therapy: Pilot results. Behavior Research and Therapy, 41(4), 403–411.

Gaudiano, B.A. & Herbert, J.D. (in press). Believability of hallucinations as a potential mediator of their frequency and associated distress in psychotic inpatients. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy.

Gifford, E.V., Kohlenberg, B.S., Hayes, S.C., Antonuccio, D.O., Piasecki, M.M., Rasmussen-Hall, M.L. & Palm, K.M. (2004). Applying a functional acceptance based model to smoking cessation: An initial trial of acceptance and commitment therapy. Behavior Therapy, 35, 689–705.

Gratz, K.L. & Gunderson, J.G. (2006). Preliminary data on an acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy, 37, 25–35.

Gregg, J.A. (2004). A randomized controlled effectiveness trial comparing patient education with and without acceptance and commitment therapy. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Nevada, Reno.

Hayes, S.C. (1984). Making sense of spirituality. Behaviorism, 12, 99–110.

Hayes, S.C. (1993). Analytic goals and the varieties of scientific contextualism. In S.C. Hayes, L.J. Hayes, H.W. Reese & T.R. Sarbin (eds), Varieties of scientific contextualism (pp. 11–27). Reno, NV: Context Press.

Hayes, S.C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35, 639–665.

Hayes, S.C., Barnes-Holmes, D. & Roche, B. (eds) (2001). Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Plenum Press.

Hayes, S.C., Bissett, R., Roget, N., Padilla, M., Kohlenberg, B.S., Fisher, G., Masuda, A., Pistorello, J., Rye, A.K., Berry, K. & Niccolls, R. (2004a). The impact of acceptance and commitment training on stigmatizing attitudes and professional burnout of substance abuse counselors. Behavior Therapy, 35, 821–836.

Hayes, S.C., Luoma, J., Bond, F., Masuda, A. & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes, and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1–25.

Hayes, S.C. & Strosahl, K.D. (eds) (2004). A practical guide to acceptance and commitment therapy. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Hayes, S.C., Wilson, K.D. & Strosahl, K.D. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press.

Hayes, S.C., Wilson, K.G., Gifford, E.V., Bissett, R., Piasecki, M., Batten, S.V., Byrd, M. & Gregg, J. (2004b). A randomized controlled trial of twelve-step facilitation and acceptance and commitment therapy with polysubstance abusing methadone maintained opiate addicts. Behavior Therapy, 35, 667–688.

Hayes, S.C., Wilson, K.W., Gifford, E.V., Follette, V.M. & Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1152–1168.

Horvath, A.O. (2001). The alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38, 365–372.

Kohlenberg, R.H., Kanter, J.W., Bolling, M.Y., Parker, C. & Tsai, M. (2002). Enhancing cognitive therapy for depression with functional analytic psychotherapy: Treatment guidelines and empirical findings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 9, 213–229.

Kohlenberg, R.J. & Tsai, M. (1991). Functional analytic psychotherapy: A guide for creating intense and curative therapeutic relationships. New York: Plenum.

Linehan, M.M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

Lundgren, T. & Dahl, J. (2005). Development and evaluation of an integrative health model in treatment of epilepsy: A randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of a short-term ACT intervention compared to attention control in South Africa. Paper presented at the Association for Behavior Analysis, Chicago.

McCracken, L.M., Vowles, K.E. & Eccleston, C. (2005). Acceptance-based treatment for persons with complex, long standing chronic pain: a preliminary analysis of treatment outcome in comparison to a waiting phase. Behavior Research and Therapy, 43, 1335–1346.

McHugh, L., Barnes-Holmes, Y. & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2004). Perspective-taking as relational responding: A developmental profile. Psychological Record, 54, 115–144.

Richards, J.M. & Gross, J.J. (in press). Personality and emotional memory: How regulating emotion impairs memory for emotional events. Journal of Research in Personality.

Segal, Z.V., Williams, J.M.G. & Teasdale, J.T. (2001). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Press.

Strosahl, K.D., Hayes, S.C., Bergan, J. & Romano, P. (1998). Assessing the field effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy: An example of the manipulated training research method. Behavior Therapy, 29, 35–64.

Zettle, R.D. & Hayes, S.C. (1986). Dysfunctional control by client verbal behavior: The context of reason giving. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 4, 30–38.

Zettle, R.D. & Raines, J.C. (1989). Group cognitive and contextual therapies in treatment of depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45, 438–445.