The border separating Alaska and Canada stretches 1,538 miles from the tip of Southeast Alaska on the Pacific Ocean up to the Arctic Ocean and Beaufort Sea.

GLIMMERS OF GOLD

BORDER DISPUTE HEATS UP

Alaska’s border with Canada is one of the great feats of wilderness surveying. Marked by metal cones and a clear-cut swath 20 feet wide, the boundary is 1,538 miles long.

The line is obvious in some places, such as the Yukon River valley, where crews cut a straight line through forest on the 141st Meridian. In other areas, like the summit of 18,008-foot Mount St. Elias, the boundary is invisible.

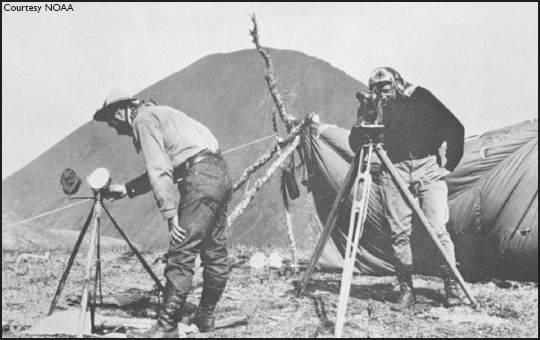

Starting in 1905, surveyors and other workers of the International Boundary Commission trekked into some of the wildest country in North America to etch a new boundary into the landscape.

But there was no border in 1867, when the U.S. purchased Alaska from Russia for 2 cents an acre. And the lack of an agreed-upon boundary caused problems from the get-go.

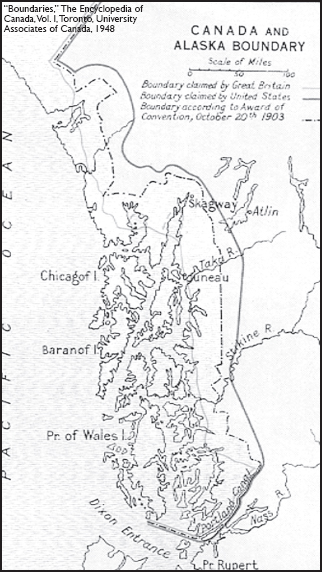

Maps of the time showed more land belonging to the Russians than was stipulated in an 1825 treaty between Russia and Great Britain. That treaty divided the Northwest American territories between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Russian-American Company trading areas and described the boundary as following a range of mountains in Southeast Alaska parallel to the Pacific Coast – but in some places there were no mountains.

In 1872, British Columbia petitioned for an official survey to set the boundary, however the United States repeatedly refused, claiming it would cost too much.

The border separating Alaska and Canada stretches 1,538 miles from the tip of Southeast Alaska on the Pacific Ocean up to the Arctic Ocean and Beaufort Sea.

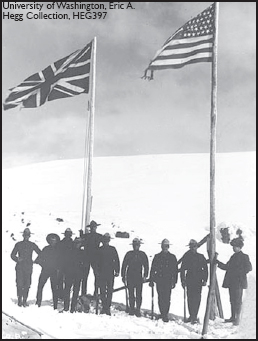

Mounties guard the Canada/Alaska border at the turn-of-the-last century.

Canada surveyed the boundary at the Stikine River in 1877, so it could set up a customs station to collect duty on goods headed to the Cassiar gold fields – discovered in 1872. In 1887-1888, and again in 1895, William Ogilvie surveyed the area around the Fortymile gold discoveries.

But it was the Klondike Gold Rush that brought the boundary issue to a head. When every square foot of ground could yield enormous wealth, the exact location of the border became critical. In fact, the total value of the gold mined in the Yukon was nearly $2.5 million in 1897 and almost $22.3 million in 1900.

The Canadians sent a detachment of North-West Mounted Police to the head of the Lynn Canal, a main gateway to the Yukon, in the late 1890s. Canadian officials wanted ownership of Skagway and Dyea, which would allow Canadians access to the Klondike gold fields without crossing American soil. Canada asserted that that location was more than 10 marine leagues from the sea, which was part of the 1825 boundary definition.

But prospectors flooding into Skagway didn’t agree. Some say that a group of heavily armed Americans demanded the Canadian flag at the police post be taken down or the Americans would shoot it down. Americans thought that the head of Lake Bennett, another 12 miles north, should be the boundary between the two territories.

The Canadians retreated and set up posts on the summits of the Chilkoot Pass and White Pass – each post equipped with a mounted Gatling gun.

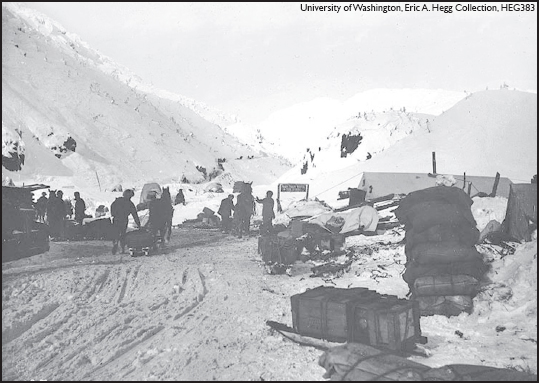

Stampeders heading toward the gold fields of the Klondike pitched tents along the shores of Lake Bennett, pictured above in 1898.

U.S. troops stationed at Dyea during the Klondike Gold Rush tried to keep peace and order among the stampeders.

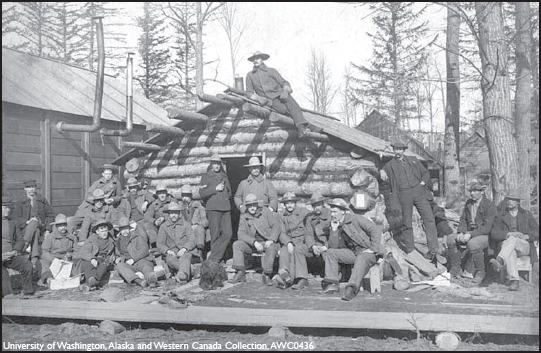

Troops perform drills at Fort Selkirk, which became the headquarters of the Canadian Army’s Yukon Field Force in 1898.

The Yukon Field Force, a 200-man army unit, then set up camp at Fort Selkirk. From there, soldiers could be dispatched quickly to deal with disputes at either the coastal passes or the 141st Meridian.

The provisional boundary was grudgingly accepted, but in September 1898, serious negotiations began in Quebec City between Canada and the United States to settle the issue.

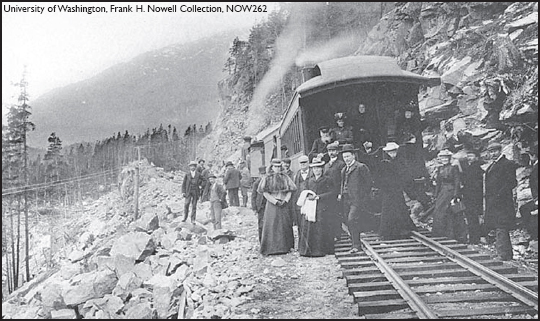

While officials were mulling over what to do about the border, other people were busy building the White Pass and Yukon Railroad through the disputed territory. And they had their share of problems, too.

In 1898, the sticky issue of the boundary line arose as the railroad approached a section of country that the Canadians considered theirs. But quick thinking of a man named Stikine Bill Robinson saved the day for the Americans.

At that time, both the Canadians and the Americans claimed the land as far down as tidewater on Lynn Canal in Southeast Alaska. Relations between the two had become strained, with the North-West Mounted Police stationed at Skagway and U.S. troops stationed at Camp Dyea at the head of navigation. As the tracks of the White Pass and Yukon Railroad approached the summit of the pass, the tension mounted.

A Canadian guard was pacing a beat there to stop construction, and the railroad men were told they could come no farther, since it was British territory.

Stikine Bill went to the summit as an unofficial ambassador. The story goes that he had a bottle of Scotch whisky in each coat pocket and a box of cigars under each arm. When the guard woke up many hours later, the construction gang was working a mile down the shore of the lake.

The hardest part of the building of that railroad was over when the summit of White Pass was reached on Feb. 20, 1899, but other problems arose along the route.

Some of which were posed by Soapy Smith and his gang.

Their interference was mostly of the nuisance type, such as starting shell games along the trail and attempting to operate liquor and gambling dives near the camps.

A White Pass and Yukon Railroad train rests at the 2,900-foot level of the Alaska-Canada boundary, 13 miles northeast of Skagway in Southeast Alaska, in 1899.

Michael J. Heney, contractor of the White Pass and Yukon Railroad, had one strict and simple rule: no liquor allowed in camp.

One of Soapy’s men, however, set up such a tent dive near Camp 3, Rocky Point. Heney ordered him off.

The man refused, saying he had as much right to be there as Heney. And maybe he did.

But Heney, like Stikine Bill, was never a man to split hairs over a technicality. He went to the camp foreman, a man by the name of Foy, and pointing to a big overhanging cliff just above the drinking den, told Foy to take the cliff down.

“That rock has got to be out of here by 5 a.m. tomorrow,” Heney said within earshot of Soapy’s cohort.

Early the next morning, Foy sent a crew to place a few sticks of dynamite in the rock cliff. The men reported all ready at 10 minutes to 5 a.m. Five minutes later, Foy sent a man to the tent to rouse the occupant, who refused – with colorful language – to get up so early.

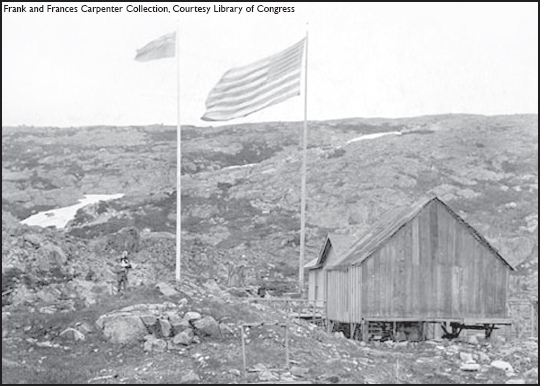

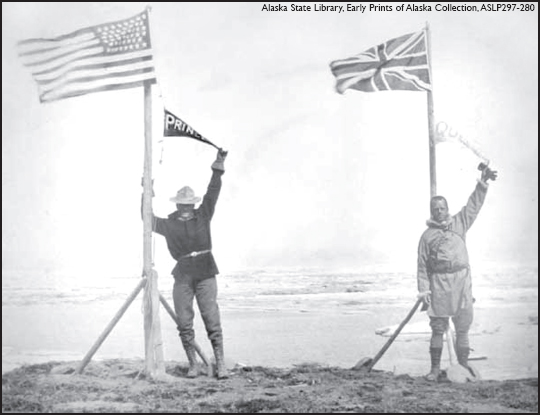

The Alaska-Canada border, shown here in 1904 somewhere along the boundary with American and Canadian flags flying, passes through remote wilderness areas.

Klondikers, like those shown here stowing their supplies and camping just below the summit of White Pass in 1898, made easy targets for con men and bootleggers.

Foy walked into the man’s tent.

“In one minute by this watch I am going to give the order to touch off the time fuse,” Foy said. “It will burn for one minute, and then that rock will arrive here or hereabouts.”

The man in bed told Foy where to go.

But Foy remained calm.

“I’m too busy to go there this morning,” Foy told the fellow. “But you will, unless you jump lively. FIRE!”

Foy used the remaining 60 seconds to retire behind a projecting cliff, where he was joined 10 seconds later by the tent’s owner. Together they witnessed the blast – and the demolition of the tent and its liquor supply.

“That rock is down, sir,” Foy later reported to Heney.

“Where is the man?” Heney asked.

“The last I saw of him he was high tailing down the trail in his red flannels, cursing at every step,” Foy said.

A six-man tribunal was established to finally resolve the boundary issue in 1903. Britain appointed Baron Alverstone, the Lord Chief Justice of England, Sir Louis A. Jetté, Lieutenant Governor of the Province of Quebec, and Allen B. Aylesworth to the panel.

President Theodore Roosevelt chose Secretary of War Elihu Root, Massachusetts Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge and Arthur Turner, ex-Senator from Washington, to represent America.

Roosevelt also sent word that if the panel did not settle the dispute to his liking, he would send in the U.S. Marines.

The United States claimed a continuous stretch of coastline, unbroken by the deep fiords of the region. Canada demanded control of the heads of certain fiords, especially the Lynn Canal, as it gave access to the Yukon.

Canada was confident that it would receive British support in the boundary dispute. Not only was it a British colony, it also had helped Great Britain in the Boer War. However, the British were more concerned about their relations with America than with Canada. They needed U.S. steel and support of the Americans for an arms race with Germany.

After three weeks of deliberations, the British representative sided with the three Americans, and the committee rejected the Canadian claims by a vote of four to two. The Alaska-Canada border was established on paper and various expeditions ordered to survey the vast area.

A boundary survey crew travels into Alaska’s wilderness to officially mark the border between Alaska and Canada in 1904.

In 1904, crews from both Canada and the United States started work on the panhandle of Southeast Alaska. They used boats, packhorses and backpacks to reach the remote mountains.

A formal treaty was signed in 1908 between the United States and Great Britain setting up the International Boundary Commission to mark the boundary officially.

A crew signals with heliograph near Monument 92 along the Alaska-Canada boundary.

Thomas C. Riggs, who served as governor of Alaska from 1918-1921, was at this time a crew chief for the International Boundary Commission. He spent eight summers marking the border and called them the happiest time in his life. When Riggs and his crew tied in the last section of the border around McCarthy in August 1914, he sent a telegram to his supervisor that read: “Regret my work completed.”

In 1925 the treaty was amended. It created a permanent International Boundary Commission to keep an accurately located and visible border. The markers are shaped like the Washington Monument and are to be placed within sight of one another.

After setting the final point on the Alaska-Canada boundary on the shore of the Arctic Ocean, Thomas C. Riggs and J.D. Craig stand in front of flags representing each country on July 15, 1912.