Sid Grauman offered vaudeville-style entertainment from tents in Nome during the gold-rush days.

GOLD-RUSH ENTERTAINERS ARRIVE

Although the frenzied gold seekers of the North lacked most of the luxuries, not to say necessities, of civilized living, they did have theaters – even opera houses.

There had been entertainment in California’s gold rush of 1849, but never had there been such garish and colorful entertainers as in the days of ’98. And many of them went on to fame and fortune.

Sid Grauman, later owner of Hollywood’s Grauman’s Chinese Theatre and high priest of Hollywood’s cinematic palaces, started his career producing tent shows in Nome. Even before that he had been Dawson’s foremost newsboy, and he never became so lordly that he disowned his Klondike newsboy days. In fact, he credited them as giving him the ideal background for his later career.

Sid Grauman offered vaudeville-style entertainment from tents in Nome during the gold-rush days.

Another future showman early discovered that a man would spend his last dollar to be amused. Alexander Pantages concluded that supplying amusement was sounder business than supplying supposedly primary needs. Like Grauman, he started in Dawson and ended up at Nome. His Pantages Orpheum provided the best show in town. After he returned to the states, he started acquiring film palaces and ended up selling his circuit for $24 million.

Most of the actors and actresses providing gold-rush entertainment were “waitresses, box hustlers, salesmen, tinhorn gamblers and the usual hangers-on of a mining camp,” sources reported. A few, however, were professionals – and some went on to stardom.

Alexander Pantages was born on the Greek island of Andros. A theatrical entrepreneur, he created a large and popular vaudeville circuit and amassed a fortune.

Marjorie Rambeau, for instance, who later became one of Broadway’s leading beauties, was a child performer when she came north, traveling with her mother and missionary grandmother. The mother took no chances with her little daughter and dressed her as a boy, and it was as a street urchin Rambeau made her debut. She was a great hit singing and playing a banjo at Tex Rickard’s famous Northern Saloon in Nome. Enchanted customers pelted her with gold nuggets.

Another small fry who later became famous was Hoagy Carmichael. He also entertained Tex Rickard’s customers in Nome. Only 8 years old, he was billed as the “boy wonder,” playing the piano in the Northern.

The entertainment business proved as profitable a gold mine as any of the rich claims on Bonanza Creek, and there were no lack of entrepreneurs to take advantage of the gold-seekers’ frantic search for amusement and forgetfulness.

The theaters in boomtown Dawson were perhaps the best known, but many other communities also had their “palaces of amusement.”

Some of them were quite primitive. The Wrangell Opera House was described by a traveler, Julius Price, as “a canvas-covered frame shanty … there was no attempt at scenery and the performers were particularly feeble.”

In 1897 there was an opera house in Circle City, and miners for 200 miles around would mush in to attend performances in the double-decker log building. George Snow, who once starred with Edwin Booth, put on Shakespearean plays and vaudeville acts.

A theatrical troupe marooned in Circle City one winter, when the Yukon River froze early, had to give the only play in its repertoire night after night. The play, “The Puyallup Queen,” finally palled, and after seeing it nightly for seven months, the audience rebelled and howled as loudly as the malamutes outside.

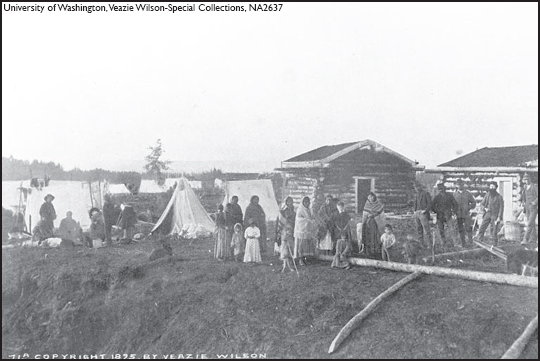

Weary miners from Circle City longed for entertainment during the gold-rush days.

When Circle City and Fortymile were emptied as a result of the Klondike strike, Dawson became the center of entertainment.

After the historic discovery of gold on Bonanza Creek in August 1896, Dawson City grew up from a marshy swamp near the confluence of the Yukon and Klondike rivers. In two years it had become the largest city in Canada west of Winnipeg with a population that fluctuated between 30,000 and 40,000 people.

Joe Ladue, a former prospector-turned-outfitter, founded the settlement on the belief that merchants in gold camps prospered more than miners. The town’s founder owned a sawmill at the mining camp of Sixtymile, and while miners staked their claims, Ladue staked out a town site.

He anticipated the coming building boom and rafted his sawmill to the new town site, which he named Dawson City in honor of George M. Dawson, a Canadian geologist who helped survey the boundary between Alaska and the Northwest Territories in the 1870s.

When he set up his sawmill in Dawson, there were two log cabins, a small warehouse and a few tents, with a total population of 25 men and one woman. Ladue sold all the rough lumber his small mill could produce, at $140 per thousand feet, to the miners working on Rabbit Creek, later renamed Bonanza.

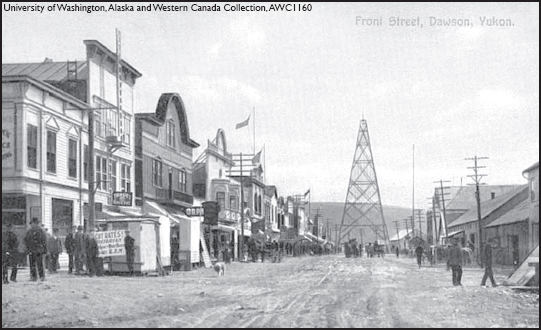

The Orpheum Theatre, pictured here on Dawson’s Front Street in the late 1890s, was a hub of vaudeville activity.

Actors perform a play on stage in gold-rush Dawson.

As word of the rich discoveries spread, more and more people headed north. Before the ice had cleared from the river, the largest rush yet to be seen in the north was under way. By late July 1897, the district had 5,000 people, and Ladue raised his lot prices in Dawson to between $800 and $8,000.

Wave after wave of gold seekers arrived, and with them came many entertainers who transformed Dawson from a mining camp into one of the most interesting cities in all of North America. It didn’t take long for theaters to pop up in the rough-and-tumble atmosphere.

Dawson’s first theater was grandiosely called the Opera House. It was in reality a log building with a bar and gambling rooms in front and a theater in the rear. A traveler who attended its opening night described it:

“A few nights after my arrival in Dawson, I visited the theatre, which for a week or more had been advertising a grand opening by means of homemade posters made by daubing black paint on sheets of wrapping paper.

“The programme was of a Vaudeville nature and included half a dozen song-and-dance ‘artists,’ a clog dancer, a wrestling match between Jim Slavin, an old-time fighter, and Pat Rooney, a Canadian.

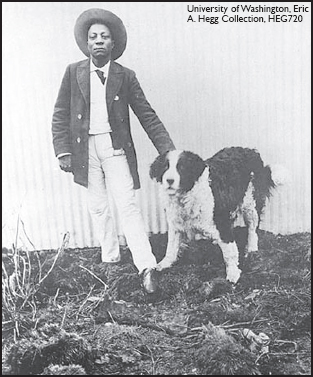

Known as Black Prince, Sanko performed at the Monte Carlo Saloon and Theatre.

“The interior of the little theatre was crowded to the walls with an audience composed almost entirely of men dressed in gaudy-colored Mackinaw clothes and fur coats and caps. The orchestra consisted of a piano, violin and a flute, and the footlights were tallow candles, whose faint light was reinforced by oddly shaped reflectors made from stray bits of tin.

“The low ceiling was of hewn logs, and the walls on either side were lined with boxes, to which the miners could gain admission by paying double the price for liquors and cigars. The stage was a narrow affair, and very little space intervened between the blue denim drop curtain and the back wall of the building.”

R.C. Kirk, author of “Twelve Months in the Klondike,” went on to describe the play as beginning at the conclusion of a medley of popular airs by the orchestra, and during the ensuing performance, he said, the audience shouted and cheered the men and women on the stage, all of whom seemed to appreciate the laughable burlesqueness of the thing.

Crowds gather at the ruins of the Opera House on Front Street after a fire destroyed the building on Nov. 25, 1897. The Monte Carlo can be seen a few doors down.

A masquerade ball was given in the Opera House on the evening before Thanksgiving 1897, and during the early hours of the following morning, the building caught fire. Before it could be checked, the building was totally destroyed.

With the disappearance of the Opera House, other dancehalls and small theaters sprang up. By the middle of the following summer, more theaters were being erected. Some of the buildings were built of logs, others made of boards and several were walled in with nothing more substantial than cloth.

The price of admission to the theaters after the Opera House burned was 50 cents, which included a drink of liquor at the bar.

By 1898, the buildings were quite elaborate; some of them even had painted scenery and dressing rooms. Theaters became increasingly sophisticated as Dawson grew from a gold camp to a thriving city.

The Pavilion was lit by gas instead of candles or coal oil, and in its dazzling light, a happy horde of gold miners from the creeks spent $12,000 on opening night.

To top that, the illumination of the Monte Carlo, which opened its theater the same year, was generated by wonders of wonders – electricity.

One of Dawson’s finest theaters was built by Arizona Charlie Meadows, a former frontiersman, cowboy, gold miner, showman and crack shot. The Palace Grand theater opened in gala style July 1899.

The Palace Grand was one of Dawson’s most beautiful theaters.

Structurally, the theater was a combination of a luxurious European opera house and a boomtown dancehall. It played host to a variety of entertainment, from wild-west shows to opera. When the show got slow, Arizona himself would get on stage and perform shooting tricks for the audience.

The Palace Grand was truly magnificent by gold camp standards. It could seat 2,200 and had several hundred “opera chairs” for the comfort of its more opulent patrons.

And what kind of entertainment was offered these patrons? It was a varied fare – songs and dances, comic sketches and one-act farces were popular. Also popular were local songs and sketches such as “Christmas on the Klondike,” “The Klondike Millionaire” and “Star of the Yukon.”

Two outstanding hits were written and produced by John Milligan. Titled “Still Water Willie,” and its sequel, “Still Water Willie’s Wedding Night,” they were satires on Klondike millionaire Swiftwater Bill Gates, who was notorious for his matrimonial imbroglios.

Other locally written plays included a one-act “Ole Olson in the Klondike,” and a full three-act comedy “Working a Lay in the Klondike.” It’s a shame that these dramas didn’t survive in print or manuscript.

Victorian drama and melodrama were presented, as well. “A Father’s Curse,” “Sentenced to Death” and “Jack the Ripper” to name a few. Later came such serious productions as “Faust,” “Camille,” “The Count of Monte Cristo” and “East Lynn.”

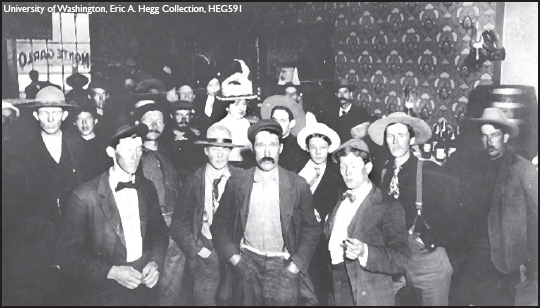

A crowd gathers in the bar of the Monte Carlo in 1898 Dawson.

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin” went over well, too. Eliza’s crossing of the ice was especially realistic and well received, even though the ice was represented by crumpled newspapers. Eliza had actually seen people crossing the ice on the frozen Yukon River, so she knew just how to do it.

However, the bloodhounds were a big disappointment, wrote A.T. Walden in his book, “A Dog Puncher on the Yukon.”

“The bloodhounds were represented by one malamute puppy drawn across the stage in a sitting position by an invisible wire and yelling his displeasure to the gods,” according to Walden.

Miners liked Little Egypt.

There were specialty acts, as well – knife throwers, trained dogs, dancing bears, magicians, tumblers, Lady Godiva and Little Egypt.

There were so many musicians wandering around Dawson it was said they outnumbered the gambling house dealers.

They sang the popular songs of the period – “There’ll be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight,” “Put Your Arms Around Me, Honey,” “Bird in a Gilded Cage,” “After the Ball,” “Ta-ra-ra Bomder-e” and “Somebody Loves Me.”

But Tappan Adney, who wrote “The Klondike Stampede of 1897-1899,” said he wasn’t impressed by the female vocalists.

“The less said the better,” he wrote, “with a few exceptions.”

One exception was Cad Wilson, whose lively personality and theme song, “Such a Nice Girl, Too,” made her the toast of Dawson. When she left after one season, it was reported that she took with her $24,000.

Another favorite was “Klondike Kate” Rockwell. She received thousands of dollars a month for singing and dancing. Among the gowns in her wardrobe was a Paris import that cost her $1,500. She was reputed to have collected $100,000 in cash and $50,000 in jewels during her Dawson reign.

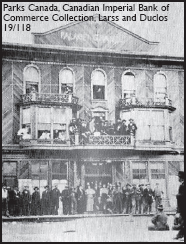

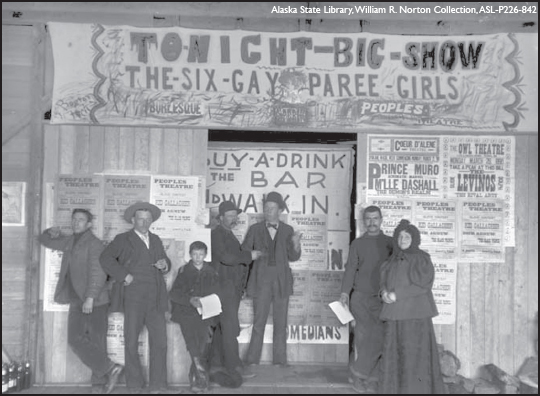

People flank the entrance to The Peoples’ burlesque theater in Skagway awaiting entry into a “Big Show.” Also advertised are fights for the Black Prince, Kid Gallagher and Dick Agnew of California. One could “buy a drink at the bar and walk in.”

The Black Prince, a prize fighter connected with the Monte Carlo, serves drinks while a man called Jack, Gertie Lovejoy, also known as Diamond Tooth Gertie, Cad Wilson – the toast of Dawson – and Tommy Dolan, brother of comedian Eddie Dolan, play cards.

Pantages persuaded her to finance a new music hall on the site of the Tivoli, which had burned down. But when the news of the Nome strike came, Pantages left without Kate. In 1906 she sued him on the grounds that he had run out on their partnership and on his promise to marry her. The suit was settled out of court.

Little 9-year-old Margie Newman sang sweet, childish and sentimental songs that brought gold out of the miners’ pockets, too, and tears from their eyes. The little “Princess of the Klondike” had a childish grace, according to a Dawson newspaper reporter of the time, “that was so moving she was frequently bombarded by coins, nuggets and boxes of candy.” She also left Dawson considerably richer.

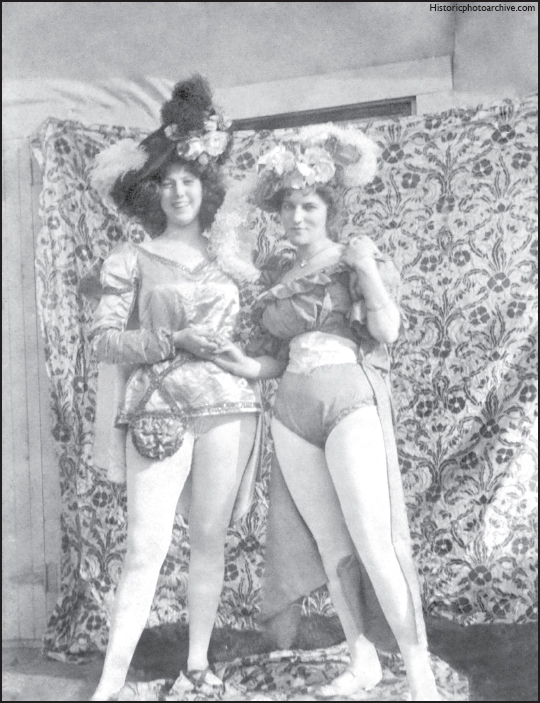

The gold-filled North Country drew entertainers like Klondike Kate Rockwell, pictured here on the left, along with an unidentified dancer, into the rugged wilderness of the Klondike and Alaska.

Klondikers pushed north from Dawson when they heard the news of nuggets lacing the beaches of Nome, pictured above.

When miners left Dawson for Nome, actors and actresses followed them north and continued to perform for audiences in newly established theaters.

But according to many reports, the most talented actor in Dawson was a donkey known as “Wise Mike.” He was usually curled up sleeping around the potbellied stove in a saloon.

“One of the practical jokes in Dawson was to get a ‘loaded’ newcomer to kick the old donkey in the ribs,” wrote Richard O’Connor in his book, “High Jinks on the Klondike.”

Mike would jump up, snorting and napping his teeth, and then attempt to wrestle with his tormentor. It was all a game with Mike, but the cheechako believed himself in mortal danger.

“After scaring his opponent out of his wits and listening appreciatively to the audience’s laughter, Mike would throw himself dog-like next to the stove again,” O’Connor wrote.

That donkey was the greatest comedian west of Broadway, according to the Dawson wags.

Even as today, there was trouble occasionally with dancers accused of indecent exposure.

At the Novelty theater, the leading attraction was Freda Maloof, “the Turkish Whirlwind Danseuse,” who performed a dance deemed so salacious that the North-West Mounted Police, established in 1873, ordered her to tone down her act. She tried to prove to the judge that there was nothing lewd in her act – that the dance she performed was an “integral part of the Turkish branch of ‘Mohammedanism.’”

However, the magistrate, who fined her $25, was not in the least impressed by her argument – perhaps because she was Greek, not Turkish.

As the diggings from Dawson to Nome began to wane around 1902, gold-rush entertainers and prospectors streamed into Alaska’s Interior where another bonanza tantalized those with golden dreams.